Lisa Florman - The Flattening of Collage

-

Upload

mlcrsoares -

Category

Documents

-

view

37 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Lisa Florman - The Flattening of Collage

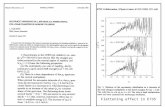

The Flattening of “Collage”*

LISA FLORMAN

OCTOBER 102, Fall 2002, pp. 59–86. © 2002 October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In his influential article “Modernism and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts,”Tom Crow took the courageous step of citing—favorably—several critical essayswritten by Clement Greenberg. Crow wanted to remind us that, in its earliesttheoretical formulations, including those advanced by Greenberg himself,modernist art was seen as thoroughly bound up with the rise of capitalism and theculture industry that attended it.1 It was, of course, to the early, overtly MarxistGreenberg (the author of “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” and “Towards a NewerLaocoon”) that Crow directed our attention; he had substantially less enthusiasmfor the arguably more dogmatic, formalist critic who, two decades later, wrote“Collage.”2 That Greenberg, Crow rightly pointed out, had become so intent ondenying any overlap between the products of mass culture and modernist artthat he refused to acknowledge the obviously commercial nature of the collageelements—the labels, the scraps of newspaper, and wallpaper—that Picasso andBraque had actually pasted into their papiers collés. Crow seemed to feel that,whatever the insights of “Collage,” they were outweighed by such oversights,and within the course of a few paragraphs he had effectively written the essayoff as irredeemably flawed.

If I find myself less willing or able to dismiss “Collage,” it is not because Ithink the formalist, Kantian Greenberg is more compelling than his Marxistpredecessor. In truth, I am far less interested in either the formalist or the Marxistalone than I am in (to borrow Stephen Melville’s phrasing) the Hegelian who

* This essay benefited from its presentation to the seminar in modern art jointly sponsored by theHistory of Art Department and the Humanities Center at Johns Hopkins University. I would like tothank Brigid Doherty for extending the invitation to deliver the paper there. I would also like to thankHarry Cooper for his generous and careful reading of the text; even those few suggestions that I didnot ultimately take helped me to clarify the finer points of the argument that I was trying to make. Amore general debt of gratitude is owed to Stephen Melville, who, early on, showed me what it mightmean to actually read Greenberg thoughtfully and with care.1. Tom Crow, “Modernism and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts,” in Modern Art in the CommonCulture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), pp. 3–37.2. Greenberg, “Collage” (1959), in Art and Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), pp. 70–83.

emerges out of the rubbing of Kant against Marx in Greenberg’s writings.3 Iwould even go so far as to suggest that Greenberg has been a powerful presencewithin art history precisely because, like Hegel, he offers us a model, albeitimperfect, of how “art” and “history” might be thought together, and of howtheir conjunction can be seen to articulate a single field: art history as distinctfrom history tout court or, perhaps more urgently at present, from either visualor cultural studies.4

All of this is by way of saying that if in what follows I engage in a close readingof “Collage” (a text that Crow describes as one of Greenberg’s “most completestatements of formal method”5), it is not so much to explicate the essay’s formalismas to draw from it an understanding of the grounds on which art might properlybe said to have a history—its history, if not fully separate from, neither fullysubsumable into, a history of culture more broadly or generally conceived. I alsohope to show that that understanding can be turned back upon the text itself, andused to rectify some of its more evident shortcomings. Even the omissions pointedout by Crow can be addressed, I believe, by rigorously applying the logic thatGreenberg developed in the first half of the essay but failed to carry through.6

I am getting ahead of myself, however. Before we can even begin our closereading, we need to clarify precisely which text it is that we intend to read.“Collage” has all too often been taken as a straightforward revision of “The Pasted-Paper Revolution,” an essay that Greenberg wrote a year earlier, and that appearedin the September 1958 issue of ARTNews.7 The differences between the two texts

OCTOBER60

3. Melville, “Posit ionality, Object ivity, Judgment,” in Seams: Art as a Philosophical Context(Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 1996), p. 78. Of course, it remains to be seen what kind of aHegelian Greenberg actually is.4. Crow’s essay, it seems to me, largely blurs these distinctions—not only through its explicitappeal to cultural studies (primarily the work of Phil Cohen, Stuart Hall, and Tony Jefferson), but alsothrough its implication that the autonomy of art, on which rests whatever claim art history may have tooccupying a distinct field, actually originates elsewhere. Crow writes, for example, that “the formalautonomy achieved in early modernist painting should be understood as a mediated synthesis ofpossibilities derived from both the failures of existing artistic technique and a repertoire of potentiallyoppositional practices discovered in the world outside” (p. 29). Similarly, although Crow begins byregarding the avant-garde as a resistant subculture like those studied by Hall and Jefferson, he closeshis argument with the suggestion that it in practice only borrows from such groups. Thus: “In theirselective appropriation from fringe mass culture, advanced artists search out areas of social practicethat retain some vivid life in an increasingly administered and rationalized society” (p. 35). 5. Crow, “Modernism and Mass Culture,” p. 8.6. In this ambition to turn what I take to be the strongest arguments within “Collage” back uponthat text itself, I feel a bit of the same hesitation expressed by T. J. Clark when he admitted that he was“genuinely uncertain as to whether [he was] diverging from Greenberg’s argument or explaining itmore fully.” In my case, there is undoubtedly some truth to both claims—though I trace my ambivalenceto “Collage” itself, which seems to lay out two distinct and even contradictory models of how modernismworks. For Clark’s analysis, “Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art,” see Francis Frascina, ed., Pollock andAfter: The Critical Debate (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), pp. 47–63.7. Reprinted in Clement Greenberg, Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago:1993), vol. 4, pp. 61–66. “The Pasted-Paper Revolution” is in turn something of a reworking of a reviewof The Museum of Modern Art’s Collage exhibition that Greenberg wrote a decade earlier and publishedin The Nation 27 (November 1948).

8. The situation is not helped by the fact that “The Pasted-Paper Revolution” was included inGreenberg’s Collected Essays and Criticism, while “Collage” was not. Even if that editorial decision wastaken in view of the still ready availability of Art and Culture, it is likely to discourage any directcomparison of the two texts, and so to reinforce the impression that the differences between themare relatively minor.9. It might seem that by beginning, as I do, at the end of “Collage,” I am willfully flouting theorder of the argument as it is actually presented, and thereby altering it in some fundamental way. Iwould counter, however, that one of the things that characterizes “Collage” (and makes it more than alittle Hegelian) is that no part of it is fully explicable in isolation. Everything is to be understood in thecontext of the whole, with the rather awkward qualification that that whole in turn depends entirely onthe individual moments comprising it. The strategy that I have adopted here—to start at theconclusion, leap to the beginning, and then work my way forward to the end—is designed to simulate,as efficiently as possible, the multiple readings that in fact led up to the interpretation I will offer.10. “The Pasted-Paper Revolution” (as in note 1), p. 65. It has become customary among art histori-ans, especially those concerned with Cubism, to distinguish between the more general category of“collage” and the subset “papier collé.” The latter term is usually reserved for works whose elements arelimited, as the name implies, to pieces of pasted paper (often with pencil or charcoal drawing overtop),whereas collages may include a wider array of materials—everything from rope and fabric to pieces ofmetal or wood. (As a result, collage appears to open out more readily onto practices perhaps bestdescribed as sculptural, whereas papier collé seems to maintain a much closer attachment to the fieldof painting.) Because Greenberg does not distinguish between the two terms, and in fact neveremploys the phrase “papier collé,” I have used them more or less interchangeably here. Nevertheless,as Harry Cooper pointed out to me, the change of title—from “The Pasted-Paper Revolution” to“Collage”— suggests that Greenberg did in fact recognize a distinction between the two practices. Itmay even be that we should read the switch to “Collage” as an indication of Greenberg’s growing sensethat, in the end, collage would prove the more “revolutionary” of the two, or at least the more pervasiveand so the more historically consequential.

have, as a result, been frequently elided.8 But “Collage” is more than twice as longas its predecessor, and, although much of the additional material can be passedoff as simply providing greater detail to the existing argument, the essay alsoincludes two subjects nowhere raised in “The Pasted-Paper Revolution”—Picasso’sand Braque’s cultivation of the sculptural aspects of Cubism, and the later (that is,post–1915) paintings of Juan Gris—that significantly alter the argument’s overallshape. To the extent that Greenberg’s desire to incorporate these subjects intohis narrative seems likely to have been what occasioned the rewriting, it mightbe worth our while to examine them briefly before taking up a properly sequentialreading of the text. We will see as we proceed that the two subjects are closely, ifnegatively, related in the unfolding narrative of “Collage.” For our purposes,though, it probably makes sense to disentangle them momentarily and attendfirst to Greenberg’s discussion of the paintings by Gris, which serves as a sort ofcoda to the essay as a whole.9

While Gris’s work had been mentioned in “The Pasted-Paper Revolution,” theemphasis there was, understandably, on his papiers collés, and Greenberg’s judgmentwas largely negative; Gris’s collages were held to “lack the immediacy of presence ofPicasso’s and Braque’s.”10 In “Collage,” although essentially the same charge isrepeated, Greenberg follows it with praise for Gris’s later paintings, again, specificallythose done in 1915 and the several years following. Greenberg claims that the paint-ings effectively recapitulate and clarify the most important achievements of Picasso’s

The Flattening of “Collage” 61

and Braque’s earlier papiers collés. He points in particular to Gris’s “sonorous”blacks—to the way that they initially constitute themselves as shapes (rather than shad-ows) and so establish an ambiguous relation to both adjacent shapes and the plane ofthe picture as a whole. In Greenberg’s eyes, the brilliance of a work like Gris’s 1916Still Life lies in the fact that it demonstrates, “perhaps more clearly than anything byPicasso or Braque, something which is of the highest importance to Cubism and tothe collage’s effect upon it: namely, the liquidation of sculptural shading.” In suchworks, Greenberg adds, “the decorative is transcended and transfigured.”11

The essay leaves little doubt that these twinned accomplishments—theliquidation of sculptural shading and the transcending of the decorative—arecentral to Greenberg’s assessment of Gris’s paintings, just as they are to his estimationof Cubist collage. From the essay’s opening sentence, it is also made clear that thatestimation is considerable: “Collage was a major turning point in the evolution ofCubism,” we are told, “and therefore a major turning point in the whole evolution of

11. “Collage,” pp. 81–82.

Juan Gris. Still Life.1916. © 1998 The

Detroit Institute of Arts.

modernist art.”12 What remains unexplained in “Collage” itself is why the history ofmodernist art should have pivoted upon a dual rejection of sculptural shading andthe sort of decorativeness that Gris’s paintings are likewise seen to have overcome.In order to flesh out the logic underlying this particular view of modernism, wewill need to take a brief detour through a couple of other essays by Greenberg,including what is surely his most programmatic (and controversial) statement onthe subject, “Modernist Painting.”

As Crow and others have accurately pointed out, Greenberg’s interest inmodernism was fueled from the start by a deep anxiety over the fate and identityof art. In his earliest essays, he cast the argument in explicitly Marxist terms:capitalism’s inexorable commodification posed a serious threat to culturalstandards and values, and only the radical experiences afforded by avant-garde artoffered any real hope of saving painting, for example, from being turned into aform of “relatively trivial interior decoration.”13 In his later writings Greenberg’sterms are rather less political, but he continues to hold modernism responsiblefor “the whole of what is truly alive in our culture.”14 Its resistance to the deadeningeffects of contemporary society is staged, he argues, not through any direct critiqueof either those effects or their cause, but rather through the processes of “self-criticism”: “I identify modernism with the intensification, almost the exacerbation,of the self-critical tendency that began with the philosopher Kant.” In “ModernistPainting,” Greenberg argues that such self-criticism is used not to subvert the“self” in question, but to entrench it more firmly; and he warns that activitiesunable to avail themselves of this sort of self-critique are those most likely todisappear, “to be assimilated to entertainment pure and simple.”15 The arts, heexplained, having recognized their vulnerability, discovered that they “could savethemselves from this leveling down only by demonstrating that the kind ofexperience they provided was valuable in its own right and not to be obtained fromany other kind of activity.” Each art, however, had to perform this demonstration onits own behalf:

The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the specific effectsof each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed

The Flattening of “Collage” 63

12. Ibid., p. 70.13. “Towards a Newer Laocoon,” Partisan Review ( July–August 1940); reprinted in Greenberg’sCollected Essays, vol. 1, p. 24. It is, I think, a bit difficult to know how serious a threat to art capitalismactually poses. No doubt there are many who feel that Greenberg’s anxiety in this regard is misplaced—either because they hold art to be inviolable or because, on the contrary, they celebrate its involvementwith commodity culture. I myself, however, am inclined to agree with Stephen Melville when he writes,in a discussion of Greenberg’s modernism, that the “fear we attribute to the world of art is not bizarre;it is based on the way things of culture increasingly do appear to die, to cease to count, in our world:not with a bang, but a whimper. It is, among other things, fear of Muzak” (Melville, Philosophy BesideItself: On Deconstruction and Modernism [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983], p. 8). Alsosee Melville’s entry on Greenberg in The Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (New York: Oxford University Press,1998) vol. 2, pp. 335–38. 14. Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” in Collected Essays, vol. 4, p. 85.15. Ibid., p. 86.

from or by the medium of any other art. Thus would each art berendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standardsof quality as well as of its independence.16

We would perhaps do well to take note of the quotation marks that appear in thispassage around the words “pure” and “purity.” They seem to indicate a certainambivalence on Greenberg’s part, a dissatisfaction, even, at having had to resort tothese terms.17 If we disregard the scare quotes, and so assume that the language ofpurity precisely captures what Greenberg had in mind, we will feel ourselvesinvited to imagine the history of modernist art as a progressive paring away of theinessential, so as to reveal in the end the final truth or essence of each art. Greenberghimself unfortunately appears to have accepted this invitation at a number of placeswithin “Modernist Painting,” perhaps most infamously in his discussion of the“ineluctable flatness” of painting’s material support. “Because flatness was the onlycondition painting shared with no other art,” Greenberg concluded, “Modernistpainting oriented itself to flatness as it did to nothing else.”18

It is an unhappy fact of the reception of Greenberg’s criticism that thisreductive account of modern art’s relation to medium has become the acceptedreading of “Modernist Painting,” and is held, moreover, to be exemplary ofGreenberg’s writings on these matters as a whole. Such a reading has nourishedthe belief that Greenberg was committed to little more than painting’s assertionof its literal surface, a commitment that is easily and rightly written off assuperficial.19 Whether or not “Modernist Painting” can actually sustain such aninterpretation, “Collage” clearly cannot. In fact, one of my hopes for the present

OCTOBER64

16. Ibid. 17. For a reading of “Modernist Painting” that does take those quotation marks fully into account,see Stephen Melville’s Philosophy Beside Itself, p. 4ff. Of particular relevance to the argument I hope tomake here is the following passage, from page 7, in which Melville draws out the implications ofaccepting the idea that art might, in fact, be something capable of “assimilation to entertainment pureand simple”:

We want, then, to say that it is an essential possibility of art that it can mistake itself in acertain way. In so doing, we rule out any radically aestheticist position from the beginning,and this means that we are going to be able to use notions like purity only if they aresomehow bracketed; we have in effect already built an impurity into our notion of art ina way that cannot be overcome. At the same time, because we have begun from an effortto take a certain kind of threat seriously, we are forced to speak of something like“purity” as a central project for or aspiration of art. And with this double handling of“purity,” we have installed a dialectical motor capable of generating a real history operatingin something other than logico-aesthetic space—a space organized by a desire to continuethe enterprise of art and not a desire to offer “theoretical demonstrations.”

18. “Modernist Painting,” p. 87.19. See, for example, Christine Poggi, “‘The Pasted-Paper Revolution’ Revisited,” in The Encyclopedia ofAesthetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), vol. 1, p. 392. Although Poggi concedes thatGreenberg was “an astute observer of the relational, ever-shifting value of surface and volume in Cubistworks,” she finds both “The Pasted-Paper Revolution” and “Collage” to be marred by Greenberg’s“continued [assumption] that the pictorial ground was an a priori fact whose integrity must be affirmed.”

essay is that it will encourage a reversal of the usual priority of things, so that“Modernist Painting” will begin to be read through the corrective lens of“Collage.” The reversal would allow us to see the appeals to medium-specificity in“Modernist Painting” as something other than a narrow essentialism, and the self-criticism that the essay claims to be definitive of modernist art as quite distinctfrom the self-reference for which it is generally mistaken.

Indeed, the idea that Greenberg holds to an exclusively purist conception ofthe arts is readily given the lie by his insistence in “Collage” on the sculpturaldimensions of Cubism. Picasso and Braque are credited there with having producedin their early pasted-paper works “the illusion of forms in bas-relief,” and, beforethat, of having been “crucially concerned, in and through their [paintings], withobtaining sculptural results by strictly nonsculptural means.”20 These observationsplay an important role in what, I will argue, is the essay’s clear demonstration thatGreenberg’s history of modernist art is, far from being a simple linear progressionto an essence, in fact fully dialectical. We will want to look carefully over thecourse of the remainder of this essay at the exact nature of that dialectic. For thetime being, though, it may be enough to remark how, in the history of modernist(which is to say, medium-specific) art recounted in “Collage,” the medium ofpainting draws at certain (self-)critical moments on the resources of sculpture—as it does no less on those of papier collé.

“Collage” also makes plain the absurdity of the notion that modernist paintingwas oriented solely toward the revelation of the “ineluctable flatness” of its materialsupport. We can see easily enough for ourselves that, had it only been a matter ofthat, there would have been little to distinguish a modernist painting from, say,the wallpaper against which it hung, and so little guarding against the medium’sdegeneration into “relatively trivial interior decoration.” “Collage” is very clear onthis point. Literal flatness is a condition that modernist painting had to acknowledge,but to which it refused to be fully reconciled: “Painting had to spell out, ratherthan pretend to deny, the physical fact that it was flat, even though at the sametime, it had to overcome this proclaimed flatness as an aesthetic fact” were it tobecome a successful painting.21 The “sculptural” and the “decorative” thatGreenberg takes up later in his discussion of Gris can thus be seen as names for

The Flattening of “Collage” 65

20. “Collage,” pp. 75 and 71. In fact a similar point is made in “Modernist Painting,” though it hasbeen almost entirely overshadowed by those passages that seem to contradict it. The relevant sentencesare these, from page 89:

It was, once again, in the name of the sculptural, with its shading and modeling, thatCézanne, and the Cubists after him, reacted against Impressionism, as David had reactedagainst Fragonard. But once more, just as David’s and Ingres’s reaction had culminated,paradoxically, in a kind of painting even less sculptural than before, so the Cubistcounter-revolution eventuated in a kind of painting flatter than anything in Western artsince before Giotto and Cimabue—so flat indeed that it could hardly contain recogniz-able images.

21. “Collage,” p. 71; italics added.

painting’s tendency to forget one or another of these “facts” about its own field.22

(In this light, the “decorative” connotes both the ineluctable physical flatness ofthe canvas, and the limit point at which painting passes over into the extra-aestheticor merely decorative, the category, that is, of non-art.)

Having arrived at this understanding of its terms, we are perhaps finally readyto begin working our way sequentially through “Collage.” Greenberg’s exclusiveconcern at the beginning of the text is with the early Cubist paintings of Picasso andBraque. He suggests that those works took the particular forms they did as a resultof the effort to find a balance between flattened facet-planes that would emphasizethe surface and a modeling that would disrupt it, without, however, producinganything that could quite be mistaken for sculptural form. “The main problem atthis juncture,” Greenberg wrote, in reference to the paintings of 1910 and 1911,“became to keep the ‘inside’ of the picture—its content—from fusing with the‘outside’—its literal surface. Depicted flatness—that is, the facet-planes—had to bekept separate enough from literal flatness to permit a minimal illusion of three-dimensional space to survive between the two.”23 Braque had already tried toaddress this problem with what Greenberg described as “expedients,” the “token”means of the tack-with-a-cast-shadow used in the 1910 Still Life with Violin and Pitcher,or the tassels-and-studs that appeared in several other works. By producing amomentary conflation of the rearmost of the painting’s depicted planes and thephysical plane of the picture itself, these tacks and studs created a “trompe-l’oeilsuggestion of deep space on top of Cubist flatness, between the depicted planes andthe spectator’s eye.”24 Unfortunately, the effect was never more than local:“Plastically, spatially, neither the tack nor the tassel-and-stud acts upon the picture;each suggests illusion without making it really present.”25

If ultimately somewhat less than adequate, the token hardware of these earlypaintings nonetheless seems to have brought Picasso and Braque to a crucialrealization: namely, that there might be a way to overcome literal or physicalflatness by, paradoxically, bringing it to the fore. “Collage” lays out the complexityof the gambit in some detail:

If the actuality of the surface—its real, physical flatness—could beindicated explicitly enough in certain places, it would be distinguishedand separated from everything else the surface contained. Once theliteral nature of the support was advertised, whatever upon it was notintended literally would be set off and enhanced in its non-literalness. Orto put it still another way: depicted flatness would inhabit at least the

OCTOBER66

22. The “sculptural,” that is, amounts to a forgetting or a denial of the physical fact that a paintingis flat, whereas the “decorative” would denote the opposite tendency—a disregard for what Greenbergcalls the “aesthetic fact” that that flatness (the canvas’s mere or mundane physicality) must somehowbe overcome in order for the painting actually to be judged a painting.23. Ibid., pp. 71–72.24. Ibid., p. 72.25. Ibid.

semblance of a three-dimensional space as long as the brute, undepictedflatness of the literal surface was pointed to as being still flatter.26

Thus, for example, the printed or stenciled letters and numbers that, in 1911,Picasso and Braque began introducing into their compositions; the point was todraw attention through these inscriptions to the literal surface of the painting, sothat everything less obviously adhering to that surface would appear to recede indepth as a result of the comparison. When used in combination with the tokentassel-and-stud, as in Braque’s The Portuguese, the simulated typography was able toyield an even more dramatic effect. Appearing to change places in depth with thetassel-and-stud, the stenciling of The Portuguese draws the physical surface itselfmomentarily into the illusion: the surface “seems pulled back into depth alongwith the stenciling,” with the result that its presence is, for a brief instant at least,effectively canceled or negated.27

The Flattening of “Collage” 67

26. Ibid.27. Ibid., p. 74.

Georges Braque. The Portuguese.1911. © Artists Rights Society (ARS),New York/ADAGP, Paris. CourtesyGiraudon/Art Resource, New York.

The only problem was that familiarity appeared to weaken the effect. By1912 Picasso and Braque had begun selectively adding sand and other foreignmaterials to their pigments, in the hope that, by emphasizing and bringing to thefore still larger areas of the actual surface, the desired illusion might be prolonged.In the end, however, this strategy, too, proved insufficient. And, of course, it wasbound to; insofar as the intention was to overcome (and not merely to deny) theliteral flatness of painting’s material support, the effort was doomed to failurefrom the start. Again, according to “Collage,” it is precisely this nonreconciliationto flatness—to, we might say, the unavoidable conditions of its own existence—that characterized Cubism, and presumably modernist painting more generally. Itis also what generated for it a history. Faced with the impossible demand tosimultaneously spell out and overcome its literal flatness, Cubist painting wasdriven to ever more extreme measures; its history appears, as a result, as asuccession of retrospective, dialectical responses to its inability to free itself fromits own extra-aesthetic contingencies.

Alternatively, we might say: the history of Cubism was propelled by a negativedialectic. This phrasing has the advantage of pointing up the extent to which, inthe first part of the essay at least, Greenberg’s logic runs parallel to that ofAdorno, for whom art and its history were likewise the products of nonreconcilia-tion.28 Adorno’s term “negative dialectics” was clearly intended to invoke Hegel,and to suggest an opposition to the dialectic of Hegelian philosophy. But becausethat opposition is itself dialectical, there is a strong sense in which Adorno’s projectalso demands to be seen as continuous with Hegel’s own.29 The point of contentionfor Adorno is that moment posited by Hegel, the moment of absolute knowing, inwhich dialectical history is at last brought to an end. At this point, according toAdorno, all of history’s driving oppositions—between subject and object, Spiritand Nature—are made to resolve themselves, without remainder and to the benefitof Spirit, in the monumental unity of the Hegelian system as a whole. Adorno’sambition was to prize the negative, dialectical core of Hegelian thought free fromthat system and its conciliatory, undialectical conclusion. Significantly, however,Adorno refused to dismiss Hegel’s conception of a totalizing system as merely anidealistic construct (although he did adamantly deny its claims to truth). Rather,

OCTOBER68

28. Although similarities between Greenberg’s criticism and the views of Adorno have been frequentlyremarked, the most sustained comparison to date of their writings, by Peter Osborne, has insteadunderlined dissimilarities. Osborne’s presentation of Greenberg, however, is largely based on a simplifiedreading of “Modernist Painting,” with the result that Greenberg’s notion of autonomy is reduced to“the idea of specifically aesthetic ‘values’” that are aligned to “the formal properties of the physicalmedium.” Thus, for Osborne, “the idea of autonomy becomes inextricably linked within Greenberg’swork to that of self-referentiality.” As I hope I have already made clear, my ambition for the presentessay is that it will dispel precisely these associations, so that we might begin to understand Greenberg’s“self-criticism” as something other than self-referentiality. See Peter Osborne, “Aesthetic Autonomyand the Crisis of Theory: Greenberg, Adorno, and the Problem of Postmodernism in the Visual Arts,”New Formations 9 (Winter 1989), pp. 31–50.29. See, in particular, Theodore W. Adorno, Hegel: Three Studies, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993).

he saw that system as having been concretely realized in the twentieth centuryunder the forces of advanced capitalism:

Satanically, the world as grasped by the Hegelian system has onlynow, a hundred and fifty years later, proved itself to be a system inthe literal sense, namely that of a radically societalized society. . . . Aworld integrated through “production,” through the exchange relation-ship, depends in all its moments on the social conditions of production,and in this sense actually realizes the primacy of the whole over itsparts; in this regard the desperate impotence of every single individualnow verifies Hegel’s extravagant conception of the system.30

According to Adorno, modern, autonomous art—art, that is, committed toan exploration of its own formal means—allows us at least a momentary glimpseof freedom from this oppressive social reality. Such work is not easily folded intothe machinery of the culture industry, and as a result is increasingly alienatedfrom society at large. But that alienation does nothing to lessen the work’s socialsignificance; on the contrary, it creates the distance necessary for effective socialcritique. Art is social, Adorno argued,

primarily because it stands opposed to society. Now this opposition artcan mount only when it has become autonomous. By congealing intoan entity unto itself—rather than obeying existing social norms andthus proving itself to be “socially useful”—art criticizes society just bybeing there.31

As a recent commentator on Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory put it, “Autonomous art,hence, is social and historical not because it is externally determined by society,although it is that, but also because . . . it strives to stage the conflict between itselfand its determinations.”32 Its autonomy arises precisely as a result of its demonstra-

The Flattening of “Collage” 69

30. Adorno, Hegel: Three Studies, p. 27. Although it lacks the reference to Hegel, the followingpassage, from Greenberg’s “The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculpture” (1947;Collected Writings, vol. 2, p. 163), makes much the same claim:

There is also the fact that a society as completely capitalized and industrialized as ourAmerican own, seeks relentlessly to organize every possible field of activity and consump-tion in the direction of profit, regardless of whatever immunity from commercializationany particular activity may have once enjoyed.

It is this kind of rationalization that has made life more and more boring and tasteless inour country, particularly since 1940, flattening and emptying all those vessels which aresupposed to nourish us daily.

31. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. Christian Lenhardt (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984),p. 321. Except where noted, all other quotations from Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory will be taken fromRobert Hullot-Kentor’s more recent (and generally better) translation of the text.32. Gregg M. Horowitz, “Art History and Autonomy,” in The Semblance of Subjectivity: Adorno’s AestheticTheory, ed. Tom Huhn and Lambert Zuidervaart (Cambridge, Mass., and London: MIT Press, 1997),pp. 263–64.

tion that those determinations do not in fact determine—or, rather, that they onlyunderdetermine—its appearance. Autonomous work attempts to show that allpotential constraints on its freedom, whether these inhere in cultural institutions,received conventions, or the very materials out of which the work itself is made,are not in actuality constraining; only in this way can the art object resist beingassimilated to preformed categories of understanding. But, obviously, the constraintsare also required to make their appearance in the work, as it is there that they mustbe confronted and negated. Every autonomous work is bound as a result to showwhat does not bind it, and in this way necessarily reveals its inability to escapeentirely from the world it aims to transcend.33 Modern, autonomous art has ahistory, on this view, because it fails to be free and yet remains unreconciled tothat failure. Thus, in Adorno’s account, “production develops as if the new workwanted to recover what the earlier work, in becoming concretized and therefore,as ever, limiting itself, had had to renounce.”34

This, as we have seen, is very much the way that early Cubism proceeded inthe history of it recounted by “Collage.”35 Through the inclusion, first, of lettersand numbers and, later, of sand and other materials that would lend it visibletexture, the Cubist paintings of 1911 and 1912 called forth the literal surface ofthe canvas specifically as a means to its negation. If the ultimate impossibility ofthat task meant that every work was bound to a certain (ontological, rather thanaesthetic) failure, it did nothing to discourage the production of new works

OCTOBER70

33. In his excellent essay “Art History and Autonomy,” pp. 273–74, Gregg Horowitz explicitly raisesthe question of what autonomous art looks like, and offers the following pertinent response:

The traditional answer in the post-Kantian tradition of philosophical aesthetics is that itlooks like freedom, an answer that has led to the idealist valorizations of aestheticautonomy in Schiller and the young Nietzsche, Clement Greenberg at his worst, andClive Bell at his best. However, . . . the proper answer is that autonomous art looks likethe failure of freedom.

It must be said, however, that the work could not conceivably appear in any other way. “Thetotally objectivated artwork would congeal into a mere thing,” Adorno wrote; however, “if it altogetherevaded objectification it would regress to an impotently powerless subjective impulse [something withoutsubstance or visibility] and so flounder in the empirical world” (Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. RobertHullot-Kentor [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997], p. 175). 34. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, p. 209.35. It seems relevant here to note that Adorno invokes Picasso’s Cubism at a number of points withinhis Aesthetic Theory. Perhaps most directly related to the concerns of the present essay are the comments onp. 256, which discuss the papiers collés in relation to the presumed opposition between autonomousand social art. (“This dichotomization is false,” Adorno argues, “because it presents the two dynamicallyrelated elements as simple alternatives.”) Cubism is held up as the example of autonomy while,perhaps somewhat surprisingly, Surrealism is made to stand for a social art: “But cubism itself revolted,in terms of its actual content [Inhalt; here Adorno seems to be referring specifically to the appropriatedmaterials of collage], against the bourgeois idea of a gaplessly pure immanence of artworks.Conversely, important surrealists such as Max Ernst and André Masson, who refused to collude withthe market and initially protested against the sphere of art itself, gradually turned toward formalprinciples, and Masson largely abandoned representation, as the idea of shock, which dissipatesquickly in thematic material, was transformed into a technique of painting.”

One would be hard-pressed, it seems to me, to arrive at a descriptionmuch better than this. It manages to convey not only the complexity of thevisual experience afforded by Braque’s Fruit Dish, but also, in the quickeningpace of its narrative, something of the excitement that a viewer in the grip ofthat experience is likely to feel. Just here, however, in Greenberg’s evident(and understandable) enthusiasm for the papiers collés, we begin to detect asubtle shift in “Collage,” away from the negative-dialectical argument withwhich the essay began toward something much more fully and affirmativelyHegelian. By the end of the essay, in fact, we will be asked to believe that thepapiers collés managed to achieve, at last, what earlier works had not: “theseamless fusion of the decorative with the plastic,”39 which is to say, the over-coming or “sublation” of the opposition between literal and depicted flatnessesthat, until this moment, had been presented as the driving tension behind the

39. Ibid., p. 81

Braque. Fruit Dish andGlass. 1912. © ArtistsRights Society (ARS), NewYork/ADAGP, Paris.

One would be hard-pressed, it seems to me, to arrive at a descriptionmuch better than this. It manages to convey not only the complexity of thevisual experience afforded by Braque’s Fruit Dish, but also, in the quickeningpace of its narrative, something of the excitement that a viewer in the grip ofthat experience is likely to feel. Just here, however, in Greenberg’s evident(and understandable) enthusiasm for the papiers collés, we begin to detect asubtle shift in “Collage,” away from the negative-dialectical argument withwhich the essay began toward something much more fully and affirmativelyHegelian. By the end of the essay, in fact, we will be asked to believe that thepapiers collés managed to achieve, at last, what earlier works had not: “theseamless fusion of the decorative with the plastic,”39 which is to say, the over-coming or “sublation” of the opposition between literal and depicted flatnessesthat, until this moment, had been presented as the driving tension behind the

39. Ibid., p. 81

Braque. Fruit Dish andGlass. 1912. © ArtistsRights Society (ARS), NewYork/ADAGP, Paris.

development of Cubist painting. The key to this reconciliation, Greenbergsuggests, lies with papier collé’s potential for optical illusion. Of the works of1912, he writes:

Flatness may now monopolize everything, but it is a flatness become soambiguous and expanded as to turn into illusion itself—at least anoptical illusion if not, properly speaking, a pictorial one. Depicted,Cubist flatness is now almost completely assimilated to the literal,undepicted kind, but at the same time it reacts upon and largelytransforms the undepicted kind—and it does so, moreover, withoutdepriving the latter of its literalness; rather, it underpins and reinforcesthat literalness, re-creates it.40

There is a distinctly triumphalist tone to these passages, roughly of thesort that, in quest epics, typically marks the narrative climax. Here, as withthose other epics, it also tends to encourage a backward glance, a brief retracingof the circuitous path leading to this point. From a retrospective vantage, however,the route suddenly appears very different than it had on the outbound journey,when the way forward seemed much more purely ad hoc, a matter of chanceand opportunity. Now the contours of “Collage” appear to have resolved them-selves into a neatly ascending (Hegelian) spiral, whose line of development wemight easily imagine Greenberg articulating as follows: In the first turn ofevents, Picasso and Braque coupled a quasi-Impressionist, decorative flatnesswith the sort of sculptural shading that had traditionally been the hallmark ofpictorial illusion; the result was the depicted flatness of high Analytic Cubism(the paintings of, roughly, 1910 to 1912). In the next round, the continuity ofthat depicted flatness was tied to its literal counterpart—and the outcome thistime was an optical illusionism that constantly seemed to displace the surfaceand remake it elsewhere.41

It would be left to the later papiers collés and, following them, to Gris’spaintings, only to liquidate the vestiges of sculptural shading that still clung toBraque’s Fruit Dish. In this way it could be made evident that the optical illusion ofthe collages might be produced without the aid of any pictorial illusion whatsoever—that the physical surface could be displaced and re-created out of shapes that wereunimpeachably flat. Again, in the case of Gris’s paintings, it was, Greenbergargued, the prominence of their blacks that effected the desired result.

The Flattening of “Collage” 73

40. Ibid., p. 77. The corresponding passage in “The Pasted-Paper Revolution” is perhaps a littlemore direct in its presentation of the matter. With the papiers collés, we are told, “pictorial illusionbegins to give way to what could be more properly called optical illusion” (Greenberg, Collected Essaysand Criticism, vol. 4, p. 64).41. It might be said that Greenberg’s opticality functions here (and in other texts) much like absoluteknowing does for Hegel. Certainly one interpretation of absolute knowing—the one held, for instance,by Adorno—is that it represents the moment when subjectivity, having at last assimilated all otherness,brings an end to dialectical history.

The clearly and simply contoured solid black shapes on which Grisrelied so much in these paintings represent fossilized shadows andfossilized patches of shading. All the value gradations are summed upin a single, ultimate value of flat, opaque black—a black that becomesa color as sonorous and pure as any spectrum color and that confersupon the silhouettes it fills an even greater weight than is possessed bythe lighter-hued forms which these silhouettes are supposed to shade.42

In writing these sentences Greenberg presumably had in view something likethe black chevron just right of center in the lower half of Gris’s Still Life ; it doesindeed appear to take off as an independent shape, advancing in front of even thelighter-colored “newspaper” (the bluish rectangle partially inscribed “Le Journal”),which, on a different level, it serves as shadow. Here again, as Greenberg said of theearlier papiers collés, “every part and plane of the picture keeps changing placewith every other part and plane; and it is as if the only stable relation left amongthe different parts of the picture is the ambivalent and ambiguous one each haswith the surface.” Because that ambiguity arises now within a painting devoid ofsculptural modeling—and so upon a surface that would otherwise seem merelypatterned and two-dimensional—Greenberg also claims that Gris’s work hassuccessfully “transcended” the decorative: “transcended and transfigured” it intothe “monumental unity” of the painting as a whole.43

Plainly, with this declaration of a “monumental unity,” the reworking ofthe essay’s initial, negative dialectic into a more fully Hegelian doctrine ofaffirmation and reconciliat ion is complete. Greenberg’s prose is seamlessenough that, on a first reading, the labor of that reworking is not readily apparent.If, however, we can manage to resist succumbing to the rhetorical elegance ofhis argument, and so keep our eyes fixed squarely on the works in question, weare eventually bound to notice certain features of those works that were simplypapered over in the later sections of “Collage.” Even Greenberg himself engagedin this sort of revision, with the footnote he added to the essay in 1972. There headmitted that Picasso and Braque had not abandoned sculptural shading soonafter the invention of papier collé, as “Collage” had originally reported (and asthe structure of its narrative seemed to demand): in fact, “Picasso and Braquecontinued to use discrete shading off and on well into 1914, and in Picasso’s caseeven longer.”44

A similar repression seems to have been involved in Greenberg’s analysis ofGris’s paintings. Anyone at all familiar with those works is likely to be given pauseby the essay’s complete disregard of their “pointillist” passages, which are at leastas prominent a feature as are the opaque blacks. They might even be seen to produce

OCTOBER74

42. Ibid., p. 82.43. Ibid., p. 83. Specifically, Greenberg says, “And here, at last, the decorative is transcended andtransfigured, as it had already been in Picasso’s, Braque’s and Léger’s art, in a monumental unity.”44. Ibid., p. 82.

a similar effect. They might be seen, that is, not as fossilized shading, perhaps, butas reified luminosity (something akin to Seurat’s Neo-Impressionism made evenmore patterned and systematic), whose frank two-dimensionality nonethelessrefuses to adhere to the literal surface—or even to a single, consistent plane indepth.45 If Greenberg passed over these passages in silence, it was perhaps becausethey raised the specter of a decorativeness beyond all possibility of redemption ortranscendence. To the extent that they pointedly recall the stippled wallpaperthat, in 1914, Picasso pasted into several of his papiers collés, they allude toprecisely the sort of “relatively trivial interior decoration” whose proliferation,according to Greenberg, had first set modernism in motion.46

45. Note, for example, the neck of the bottle in Gris’s Still Life : Its silhouette is articulated on theleft by a field of green dots against a yellow ground, in the middle by an undifferentiated green, and atright by blue stippling on a green field. Even though it is the same green hue in all three cases—andeven though, if we make ourselves focus exclusively on it, its continuity from one field to the next isplainly evident—each area, in fact, appears to separate itself from the others as an independent shapeand to advance slightly forward of them, or else recede a little in depth. There is with these stippledareas, in other words, the same kind of spatial oscillation and ambiguity that Greenberg detailed in hisaccount of the paintings’ “sonorous” blacks.46. There are seven works in all that use this stippled wallpaper. For illustrations, see Pierre Daixand Joan Rosselet, Picasso: The Cubist Years 1907–1916, trans. Dorothy S. Blair (Boston: New YorkGraphic Society, 1979), pp. 681, 683, 685, 686, 689, 793, and 799.

Pablo Picasso. Pipe and Sheet Music. 1914. © 2002Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS),New York. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Wallpaper in general was a standard element of Picasso’s collages, and it was sofrom the very beginning: for example, an ocher-and-yellow floral pattern appearsprominently in what is probably his first papier collé, Guitar and Wineglass, fromNovember of 1912. It is a striking fact—surely more than merely coincidental—thatthe artist’s insertion of such explicitly decorative elements into his Cubist collagesfollowed almost immediately upon the very public insertion of Cubism into anexplicitly decorative context. I am thinking of the Maison Cubiste, the suite of roomsmodeling the interior of a bourgeois home that was part of the 1912 Salond’Automne.47 Displaying furniture and wallpaper patterns by a group of youngdesigners led by André Mare, the Maison also showcased the paintings of FernandLéger, Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, and many of the other so-called Salon Cubists.The participation of Gleizes and Metzinger seems particularly difficult to explain,given that they had argued in Du Cubisme—published while the Salon d’Automnewas still open and receiving visitors—that their work was the very antithesis ofdecoration.48 It appears to have been the absence of any discernible Cubist influenceupon the furnishings of Mare and his cohort that allowed Gleizes and Metzinger torationalize their involvement with the project. The antidecorative diatribe of DuCubisme was aimed specifically at the Art Nouveau belief that a painting should

47. The Salon of that year ran from October 1 until November 8.48. “Many consider that decorative preoccupations must govern the spirit of the new painters.Undoubtedly they are ignorant of the most obvious signs which make decorative work the antithesis ofthe picture” (Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, Du Cubisme [Paris: Figuière, 1912], translated inRobert Herbert, Modern Artists on Art [New York: Prentice-Hall, 1964], p. 5).

Salon bourgeois, La Maison Cubiste. Salon d’Automne,Paris. 1912. Archives André Mare, Paris.

harmonize with its surroundings. And Art Nouveau—or rather, a popularized, mass-produced version of it—was being widely marketed in the newly opened ateliers ofthe French department stores.49 If Au Printemps’s showrooms seemed to foretell afuture in which paintings would take their place within a coordinated decorativeensemble (each work designed to harmonize with the furniture, and playing upsome of its subtler hues), the more or less traditional décor of the Maison Cubistecould be seen to serve, on the contrary, as an offsetting frame, reinforcing thepainting’s autonomy and integrity. For his part, Mare hoped that an alliance withCubist painters and sculptors would give his designs a certain cachet, and sharplydifferentiate them from the mass-produced commodities marketed to the publicthrough the department stores’ displays. But, of course, the whole enterprise wasopen to multiple interpretations. Even if it was intended to underline the integrityof the Cubist paintings hanging there, and to emphasize the qualitative differencesbetween the artisanal tradition represented by Mare and the mass production ofthe department stores, the very resemblance of the Maison Cubiste to AuPrintemps’s ateliers d’art threatened to scramble those distinctions. In many ways, itsimply concretized the threat of art’s assimilation to interior decoration.

Complicating the situation further was the fact that many avant-garde artists—from the Nabis to the Fauves, and including, on occasion, Cubists such as Grishimself50—openly embraced the characterization of their work as “decorative.” Yearsafter the fact, Matisse all but conceded that their unqualified acceptance of the termhad been naive—or worse, actually complicitous with the marketing strategies of theFrench department stores:

Finally, after the rediscovery of the emotional and decorative propertiesof line and color by modern artists, we have seen our departmentstores invaded by materials, decorated in medleys of color, withoutmoderation, without meaning. . . . These odd medleys of color andthese lines were very irritating to those who knew what was going onand to the artists who had to employ these different means for thedevelopment of their form.

Finally all the eccentricities of commercial art were accepted (an extra-ordinary thing); the public was very flexible and the salesman wouldtake them in by saying, when showing the goods: “This is modern.”51

The Flattening of “Collage” 77

49. For a discussion of the Maison Cubiste within the history of the French decorative arts, seeDavid Cottington, Cubism in the Shadow of War (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998),pp. 169–79; and Nancy Troy, Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France (New Haven: Yale UniversityPress, 1991), pp. 79–102.50. In 1921 Gris informed Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler that, the dealer’s protests to the contrary, hiswork was in fact accurately characterized as “decorative.” “Clearly it is decoration,” Gris wrote. “Oneneed not be afraid of words when one knows what they signify, but all painting has always beendecoration.” Cited in Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention ofCollage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 123.51. “Matisse’s Radio Interview: First Broadcast, 1942,” cited in Poggi, In Defiance of Painting, p. 140.

As for Picasso, neither he nor Braque ever took up Matisse’s praise of the“decorative,” and, according to Kahnweiler, both were openly contemptuous ofpaintings made “to ‘adorn’ the wall.” From as early as 1907, Kahnweiler says, Picasso“perceived the danger of lowering his art to the level of ornament.”52 And yet, in themonths and years immediately following the run of the Maison Cubiste, the artistregularly incorporated wallpaper fragments within his papiers collés. What’s more, inthe case of the 1914 series, those fragments were ones that clearly pointed up thedifficulty of distinguishing modernist art (certainly of the Neo-Impressionist variety)from “relatively trivial interior decoration.”53 In this context it seems crucial to notethat the wallpapers of that series sometimes served—as they do in Pipe and SheetMusic—to duplicate the frame.54 Frames have traditionally provided the visiblemarker of a work’s autonomy, clearly demarcating the boundary between that workand everything else outside. But the frame’s own status is, for precisely that reason,ambiguous and contradictory. At once external to the painting and essential to itsappearance as a thing apart, the frame both obviously belongs to the work and, justas evidently, doesn’t.55 Picasso’s wallpaper-framed collages seem to be making ananalogous claim regarding the boundary—the all-important (in)distinction, as itwere—between modern art and the merely decorative. And they encourage us to seehis earlier wallpaper works in very much the same vein.

In Greenberg’s history of Cubism, the invention of collage had marked anepochal moment, the moment, as he said, when the decorative surface of thework was at long last “transcended and transfigured,” dissolved into the purelysubjective space of optical illusion. Of course, that history was dependent uponthe repression of the commodified, mass-produced nature of many of the elementsof Cubist collage. Unlike the collages themselves, Greenberg refused to admiteven the potential presence of the literally and commercially decorative withinthe field of modern art. Our own attention to the specific materials of thosecollages now suggests a slightly different history, one in which the invention ofpapier collé is, however, no less epochal. Through its invention, we might say,the threat of the decorative—the possibility that modern painting might in factbe assimilated to decoration (or entertainment) pure and simple—was, at longlast, openly acknowledged.56

OCTOBER78

52. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, The Rise of Cubism (1916), trans. Henry Aronson (New York:Wittenborn, 1949), p. 7; cited in Rosalind Krauss, The Picasso Papers (New York: Farrar, Straus andGiroux, 1998), p. 181.53. Tellingly, in the spring of 1914, just at the time that Picasso began working on this series, a serial-ized essay by André Mare appeared in Montjoie!, which advocated a return to primitive woodblock printingmethods for wallpaper, and blamed modern mechanical techniques for a decline in the present quality ofproduction. See Mare, “Le Papier peint,” Montjoie!, nos. 4, 5, and 6 (April, May, and June 1914).54. There are a total of four collages from the spring of 1914 that employ wallpaper frames (Daix 683,684, 685, and 787). Two of these—Pipe and Musical Score and Glass and Bottle of Bass—feature the stippledwallpaper pattern. 55. On the status of the frame and its implications for the autonomy of art, see Jacques Derrida, TheTruth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987),especially section II, “The Parergon,” 37ff.56. On the notion, and the structure, of acknowledgment, see Stanley Cavell, “Knowing and

I hasten to add that it was not, for all that, openly accepted. Just as earlierCubist paintings had foregrounded their literal surface in a determined effort tonegate it, so Picasso’s wallpaper collages seem to advertise their imbrication withthe merely decorative precisely so that they might make crucial differencesapparent.57 On this view, the project of the papiers collés is continuous with thatof earlier, Analytic Cubism, except that, where those earlier works had taken itupon themselves to acknowledge (and negate) the physical fact of their materialsurface, the papiers collés also acknowledge the social fact of painting’s equivocalposition in relation to the culture industry of late capitalism. They amount to therecognition that, if art does in fact cease to exist or to matter in this world, it willbe less because it has reified into a mere object than because it has capitulated to avoracious subjectivity, seeking pleasure, demanding entertainment.

We might compare Picasso’s use of wallpaper in this regard with his equallyfrequent employment of newspaper in the papiers collés. As Krauss has shown,newspaper was a material under considerable tension in the avant-garde world of1912.58 It had been roundly condemned by Stéphane Mallarmé, whose Symbolistaesthetic and views on the autonomy of art clearly held a strong attraction forPicasso.59 Angered by the newspapers’ increasing commodification of literature—including their ser ializat ion of novels commissioned explicit ly for thatpurpose—Mallarmé went on the offensive. He argued that, even apart from thequality of the writing it presented, the newspaper was vastly inferior to the book,in that its pages confronted the viewer with column after column of monotonousgray type. Furthermore, its composition was driven, he said, by hierarchies ofpower (which determined what would appear on the front page, what on the last);and, worst of all, it sacrificed the sensuous fold of the book to the unrelievedflatness of the open newsprint page.60

The Flattening of “Collage” 79

Acknowledging,” in Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press,1976), pp. 238–66.57. In saying this, I am largely agreeing with Christine Poggi, who has argued that Picasso’s andBraque’s papiers collés represent a “complex and paradoxical relation to mass culture,” in that theysuggest simultaneously “a denial of the precious, fine art status of traditional works of art as well as anattempt to subvert the seemingly inevitable process by which art becomes a commodity in the modernworld” (In Defiance of Painting, p. 128). To phrase things in terms of “denial,” however, sounds a distinctlyfalse note for me; it might be better to say that the papiers collés effectively recognize that the distinctness(or “purity”) art was once able to take for granted is no longer tenable. It is what each work mustdemonstrate for itself, even as it acknowledges its entanglements with the extra-aesthetic. I would alsoargue that Picasso’s and Braque’s papiers collés are not identical in this regard (see note 66 below). 58. Krauss, “The Motivations of the Sign,” Picasso and Braque: A Symposium, ed. Lynn Zelevansky(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1992), pp. 261–86. See also Poggi, In Defiance of Painting, p.141ff.59. On the relation between Picasso and Mallarmé, see David Cottington, “Cubism, Aestheticism,Modernism,” in Picasso and Braque: A Symposium, pp. 58–72.60. Stéphane Mallarmé, “Le Livre, instrument spirituel,” in Oeuvres completes (Paris: ÉditionsGallimard, 1945), pp. 378–82. See also Christine Poggi, “Mallarmé, Picasso, and the Newspaper asCommodity,” in The Yale Journal of Criticism 1, no. 1 (1987), pp. 133–51; and her revision of thatargument in her book In Defiance of Painting.

In the newspapers’ corner, by contrast, was Picasso’s friend GuillaumeApollinaire, who admired the papers for their ability to speak in a plurality ofvoices, and who, in his own heteroglossic poem “Zone,” embraced nearly all ofcommercially printed popular culture:

You read the handbills, catalogues, posters that sing out loud and clear—That’s the morning’s poetry, and for prose there are the newspapers,There are tabloids lurid with police reports, Portraits of the great and a thousand assorted stories.61

The newspapers of Picasso’s papiers collés cannot be said to adhere toeither of these positions. As Krauss has shown, they are not of a piece withApollinaire’s unqualified acceptance, yet their very appearance within the collagesplaces them at some remove from Mallarmé’s conviction that the newspapercould not possibly serve as a vehicle for genuine aesthetic experience. Rather,Picasso employed newspaper, but in such a way as to negate its most perniciouseffects. The fragments within his collages are made to embody precisely “thoseprecious aesthetic possibilities that Mallarmé had insisted were the exclusiveprerogative of the book: the capacity to figure forth the fold as that metaphysical‘turning’ of the page that opens the work of art onto the abyss or chasm ofmeaning; and the ability to transmute the gray drone of the marks on thepage” into signifiers for light, transparency, and depth.62 That we are dealingwith a determinate negation, and not some final sublation or transcendence, ismade all too apparent by those scholars who, ignoring Cubism’s dialecticalimpulse, persist in reading the columns of type as if those passages were nothingmore or other than the newspaper from and against which the work of art actuallytook shape.63

Understanding how the newspaper fragments function within Picasso’spapiers collés—and how that functioning ought to discourage us from readingthe text or attributing its views to Picasso—should by no means prevent us, however,from recognizing the potential social and political significance of the worksthemselves. As Adorno argued, such significance is won specifically through thework’s autonomy, which is to say, its overt display of nonreconciliation.64

OCTOBER80

61. Cited in, and translated by, Krauss, “The Motivat ions of the Sign,” p. 277. GuillaumeApollinaire’s “Zone” seems like an explicit riposte to Mallarmé’s assertion that “le vers est partout dansla langue où il y a rythme, partout, excepté dans les affiches et à la quatrième page les journaux,”Oeuvres completes (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1945), p. 867.62. Krauss, “Motivations of the Sign,” pp. 281–82.63. The most concerted effort in this regard is to be found in Patricia Leighten, Re-Ordering theUniverse: Picasso and Anarchism, 1897–1914 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), pp.121–42. See also Yve-Alain Bois’s “The Semiology of Cubism,” in Picasso and Braque: A Symposium, ed.Lynn Zelevansky (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1992), p. 203, where he aptly characterizes the“recourse to newspaper [as] a Mallarméan (or formalist) answer to Mallarmé’s disdain: even this productof modern industry can be deautomatized, deinstrumentalized, opacified, ‘poeticized.’”64. It is worth noting that David Cottington has recently sanctioned a similar argument for thepolitical significance of Mallarmé’s work, holding that Mallarmé’s prose poems constituted a “counter-

Whether art becomes politically relevant or indifferent—an idle play ordecorative frill of the system—depends on the extent to which art’sconstructions and montages are at the same time de-montages, i.e.,dismantlements that appropriate elements of reality by destroyingthem, thus freely shaping them into something else. The unity of thesocial criterion of art with the aesthetic one hinges on whether art isable to supercede empirical reality while at the same time concretizingits relation to that superceded reality. Art that succeeds in doing this has aprerogative: it may dismiss the question posed by political practitioners asto what it is up to and what its “message” is.65

What makes Adorno’s comments so thoroughly apposite to the presentcontext is not simply their explanat ion of the antagonist ic relat ionshipbetween autonomous art and existent social formations, nor even their sugges-tion that the appropriate structural model for that relationship is to be foundin collage or montage.66 The relevance of his comments lies also in their impli-cation that the “decorative” names but a “frill” or extension of the “system”—whichis to say, work that is either a product of the culture industry or ready fodderfor it.

“If decoration can be said to be the specter that haunts modernist painting,then part of the latter’s formal mission is to find ways of using the decorativeagainst itself.”67 This time the words are Clement Greenberg’s, and, although theywere not written specifically as commentary on the development of Cubism andthe advent of papier collé, they manage to serve nicely in that capacitynonetheless. In fact, they seem particularly apt to an understanding of Picasso’swallpaper collages, which not only acknowledge the specter of the decorative, butconfront that decorativeness in one of its most insidious forms: as the bland

The Flattening of “Collage” 81

discourse,” which turned the “language of dominant discourse against itself.” Ironically, however,Cottington—who has also sanctioned and amply documented an understanding of Picasso’s Cubism inrelation to the aestheticism of Mallarmé—is unable to see the artist’s papiers collés as performing asimilar negation. Instead he argues that their “pretensions to counter-discourse are compromised” bytheir “complicity” with “the aesthetic hierarchies of dominant culture.” This, it seems to me, issymptomatic of the fact that Cottington persistently identifies references to the “popular” in Picasso’sart with the working classes (rather than with commodity culture), and refuses to consider aestheticexperience as anything other than the purview of an economic elite. See Cottington, Cubism in theShadow of War (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), especially pp. 137–43.65. For this passage, I have used the Lenhardt translation of Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory (London:Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), p. 362. The corresponding passage appears in the Hullot-Kentortranslation on pp. 255–56.66. Elsewhere in Aesthetic Theory, Adorno specifically states that the “act from which all montagederives” was Picasso’s use of newspaper in his papiers collés. See the Hullot-Kentor translation, p. 258.67. Clement Greenberg, “Milton Avery” (1958), in Art and Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), p.200. It is, I think, worth noting that, whereas “Modernist Painting” had emphasized the need forpainting to distinguish itself principally from the sculptural and the literary—that is, from “any andevery effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art”—here thoseconcerns clearly take a backseat to the threat of the decorative. And what this suggests in turn is that

prettiness of bourgeois interior decor.68 That these collages are also “de-collages,”turning the decorative against itself, is readily seen, for example, in Guitar andWineglass. Around the periphery of that work the wallpaper represents nothingother than wallpaper itself: a flat, continuous background against which the stilllife elements of the composition are arrayed. But the section just beneath thesound hole of the guitar seems drawn forward (precisely by its relation to thatoverlaid “hole”), where it is reconstituted as the guitar’s surface and so made toreside, at least momentarily, on a completely different plane in depth. It is, ofcourse, only a tentative move, an opening salvo. Yet still it seems right to declare:la bataille s’est engagé[e].

Over the next eighteen months Picasso’s means would become progressivelymore sophisticated, as he discovered ever new ways to dissolve the wallpaper’sopacity or displace its surface in depth. In Pipe and Sheet Music, for example, fromthe spring of 1914, the stippled mauve wallpaper lends itself to at least threecontradictory interpretations, each one suggesting a radically different spatialconfiguration for the elements of the picture as a whole. Like so many otherCubist still lifes, this one sets up and exploits what Christine Poggi has describedas a willful confusion between table and tableau.69 The brown rectangle at thecenter of the composition asks to be read, in one light, as a tabletop—freed fromboth gravity and perspective, but nonetheless supporting the pipe and the pageslaid beneath it, and casting a heavy shadow on the floor. In another light, however,that rectangle appears simply as the vertical plane of the picture proper; in thisreading the mauve wallpaper reverts back from its earlier designation as theshadowy surround of the table (the space of traditional easel painting), andbecomes again simply wallpaper, or at least the matte surface on which the smallcollaged still life is mounted. And still there is a third possibility. Long agoKahnweiler made the suggestion—more recently elaborated by Krauss—that thework is also capable of producing the illusion that it is not a picture frame that weare looking into, but rather the ornate frame of a mirror.70 At such moments thewallpaper continues to designate a flat, opaque surface, but it is now a surface dis-placed to the far side of the room—the wall behind our backs—with the result thatthe work acquires an almost Meninas-like spatial complexity.

OCTOBER82

modernist painting was always driven by its dialectical opposition to decoration, but—because thatthreat was too dire—the accompanying anxiety was constantly displaced onto the safer encroachmentsof literature and sculpture. In this way it became possible to reconstrue the prospect of painting’sfailure as still a failure within the realm of the aesthetic, and so to imagine that successful paintings yetremained completely sealed off from the insidiousness of “decoration.” On such matters as theypertain to Michael Fried’s notion of “theatricality,” see Melville, Philosophy Beside Itself, pp. 9–10.68. It seems to me a striking fact that Picasso’s use of patterned wallpaper is much more extensivethan Braque’s. Braque’s preference was for faux bois papers that raised questions of representation andsimilitude, but carried few of the social and aesthetic implications of Picasso’s chosen materials.69. See Poggi, “Frames of Reference: Table and Tableau in Picasso’s Collages and Constructions,” inIn Defiance of Painting, pp. 58–89.70. See Krauss, The Picasso Papers, p. 161ff.

Picasso. Guitar and Wine Glass. 1912. © 2002 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay.

It seems important here to insist that, although optical illusion plays a rolein this experience of the collage, and so also in the negation of the wallpaper’sunambiguous planarity, illusion per se does not appear to be the main goal of thework. It is but one of the means employed to undo the certainties of thewallpaper—to turn its consistently repetitive surface into a kind of arbitrary sign,which, because of that arbitrariness, lends itself to various conflicting readings, asa sort of multidimensional “pun.” We might describe Picasso’s papiers collés ingeneral as working to negate not just the literal flatness of the materials theyemploy, but also the banality of those materials. In the case of the wallpaper collagesthe material in question is superficial, ingratiating, monotonous: the kind ofsurface whose only function is to please, and which asks for nothing more thanour inattention. If we find Picasso’s collages compelling, it will be because of theway that they are able to make those materials over, by contrast, into works ofsurprising depth and difficulty. And, of course, “by contrast” should be emphasizedhere, since the process is driven by a dialectic of negation. In fact, Adorno’saccount of art’s negative-dialect ical relat ion to society at large is perhapsnowhere better seen than in Picasso’s wallpaper collages. The unrelieved repeti-t iveness of the wallpaper patterning offers an experience that is a perfectexample of perceptions conforming to preestablished categories of understanding.As the designs themselves affect no change in the pattern of our thought, theyare nothing more than “idle play,” a “decorative frill of the system.” But Picasso’scollages—the successful ones, at least—by demonstrating their nonreconciliationto the ineluctable flatness and banality of the wallpapers are able to achievesome measure of autonomy. They seem to cut themselves out from the prefabricatedworld, the world as it already exists, and to which, in some sense, they are obviouslystill attached.71

If this is not, ultimately, the argument that Greenberg made for Picasso’spapiers collés, it remains the case that it is an argument we are unlikely to havebeen able to formulate without him. Greenberg’s “Collage” opens with a cleararticulation of the negative-dialectical workings of Cubism—albeit without

OCTOBER84

71. In her recent book The Picasso Papers, Rosalind Krauss discusses several of Picasso’s wallpapercollages in terms that have substantial overlap with my analysis of those works here; indeed Krauss’s texthas informed my understanding of the papiers collés considerably. Her insistence that the relationbetween modern art and the decorative be seen as dialectical is an idea that I have obviously taken verymuch to heart. But her suggestion that we understand that dialectic on the model of “reaction for-mation”—and that Pipe and Sheet Music represents one of the earliest manifestations of that conditionin Picasso’s art—does not seem quite adequate either to registering the pervasiveness of the decorative’sthreat, or to imagining what a “healthy” response to it might be. (If every appearance of decoration inPicasso’s work is to be diagnosed as a case of reaction formation, we would have little choice but to believethat his best course would have been a more thorough repression.) I prefer to think of the papiers collésunder the model of acknowledgment: the collages openly acknowledging the presence of the decorative inorder that its worst qualities and consequences might be negated. Of course, this still leaves open thepossibility that the attempted negation will be unsuccessful and that the work in question, despite any andall intentions to the contrary, will appear merely and simply decorative. In those cases, I concede, themodel of reaction formation has a certain applicability.

couching the discussion in precisely those terms. (In general Greenberg tends toavoid theoretical terminology in favor of descriptive language that, in its bestmoments, is closely aligned to the mater ial specificit ies of the works inquestion.72) The one theoretical or philosophical term that Greenberg does use,and insist upon, is “self-criticism.” He both identifies artistic modernism with “aself-critical tendency” and warns that activities unable to avail themselves ofsuch self-criticism are those most likely to be assimilated to entertainment pureand simple. Phrased in this way—and in view of our discussion of the negativedialectic at work in “Collage”—Greenberg’s modernist “self-criticism” appearsclosely related to what Adorno referred to as art’s autonomy, its manifestlyoppositional relation to society at large. Self-criticism might be regarded, then,as yet another name for that dialectical process through which art continues tomake and preserve a place for itself in the modern world. It is self-critical only tothe extent that the works involved genuinely place themselves at stake and holdthemselves in that condition: assuming neither art’s inviolability nor, of course,its simple nonexistence.73 And those works will be successful in turn only to theextent that they are able to distinguish themselves from other kinds of objects ofcultural production—to the extent that they make some critical differencevisible. That art cannot, in the end, completely escape its resemblance to andimbrication with those other cultural products also condemns it, as we haveseen, to a certain failure. But it is just this failure that generates a history forart—which means that works can only be produced or understood in relation tothat history, and to the particular concrete works within it that make a claim onus as art.

For me at least, much of what makes Picasso’s papiers collés so compellingis their difficult, dialectical relation to the earlier history of Cubism as that history isarticulated by Greenberg in his essay on collage. And while it may be true thatthat essay misses the full significance of the papiers collés through its refusal toengage with the particularities of the materials they employ, it is also true thatart history stands open to a similar accusation in regard to “Collage.” The specificityof its argument, its nuance, has been repeatedly disregarded in favor of generalitiesand preconceptions. Admittedly, Greenberg himself, especially in “Modernist

The Flattening of “Collage” 85