FIT OR MISFIT? ITALIAN PARTIES IN EUROPE

Transcript of FIT OR MISFIT? ITALIAN PARTIES IN EUROPE

This article was downloaded by: [Northeastern University]On: 12 November 2014, At: 05:39Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

RepresentationPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrep20

FIT OR MISFIT? ITALIAN PARTIES INEUROPEEdoardo Bressanelli & Daniela R. PiccioPublished online: 04 Jul 2014.

To cite this article: Edoardo Bressanelli & Daniela R. Piccio (2014) FIT OR MISFIT? ITALIAN PARTIESIN EUROPE, Representation, 50:2, 231-244, DOI: 10.1080/00344893.2014.924432

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2014.924432

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

FIT OR MISFIT? ITALIAN PARTIES INEUROPE

Edoardo Bressanelli and Daniela R. Piccio

We depart from the argument that policy congruence between the national and the EU parties has a

role in bridging the democratic deficit of the EU. We assess it for the difficult case of Italy, where the

issue of parties’ transnational affiliation is incredibly divisive, and the party system is in a state of

flux. Using the EU Profiler data, we are able to show that its parties are remarkably congruent. Yet,

we suggest that congruence might overestimate the parties’ representative capacity.

1. Introduction

With the objective of bridging the divide between European Union (EU) politics and thecitizens, the European Commission has recommended the creation of visible links between thenational parties and the EU political parties in elections to the European Parliament (EP).‘Voters’, the Commission argued, ‘should be informed of the affiliation between nationalparties and European political parties before and during elections to the EP’.1 However,there is little evidence that national parties would be keen to implement these recommen-dations, informing potential voters of their membership of a political party at the EU level.

On the one hand, the EP has increasingly strengthened its functions and law-makingcompetences, and political parties at the European level are increasingly important: underthe Lisbon Treaty, they contribute ‘to forming European political awareness and to expressingthe will of citizens of the Union’ (art. 10.4). On the other, to the question whether these dispo-sitions reflect the empirical reality, scholars have answered overall negatively. They have com-monly pointed at the ‘second-order’ nature of the EP elections (Reif and Schmitt 1980) and atthe absence of a direct electoral linkage between the national and the EP arena (Andeweg1995; van der Brug and van der Eijk 2007) as the most critical flaws in the functioning ofthe representative processes of the EU.

Yet, in the ongoing debate on the EU democratic deficit, a growing area of research isnow focusing on the representative potential of the EU political parties (Bardi et al. 2011;McElroy and Benoit 2010, 2012; Thomassen 2009; Mair and Thomassen 2010). In particular,it is argued that even in the absence of a fully structured system of political representationat the EU level, the national parties have the power to channel citizens’ preferences to theEU. This ‘linkage’ would effectively work when a national party is affiliating with a politicalgroup in the EP that matches its policy preferences. Contrariwise, when the structure ofparty completion strongly differs among the national and the EU arenas, and a misfitamong the two party systems is then in place, citizens’ preferences would hardly find adequateexpression in the EU.

A member country of the EU where the issue of party affiliation in the EP groups appearsto be particularly salient, and contentious, is Italy. The dramatic events of the early 1990s, when

Representation, 2014Vol. 50, No. 2, 231–244, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2014.924432# 2014 McDougall Trust, London

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

a number of interrelated causes provoked the collapse of the Prima Repubblica (1948–94) anda complete reconfiguration of the parties and the party system, did not generate strong partiesand a stable party system. In the so-called Seconda Repubblica (1994–2013) frequent mergersand split-offs characterised the established parties, while the appearance of new parties andthe rapid decline of others had an impact on the party system.

This domestic turmoil could not but mirror itself at the EU level, where the Italian partieshave been among the most unstable members in the EP political groups. Here, the point canbe briefly illustrated by reflecting on the issue of transnational affiliation for the two majorItalian parties, the Partito Democratico (PD) on the left and Forza Italia (FI) on the right. Theinternal divisions of the former on membership in the Party of the European Socialists (PES)have produced a quite unique situation: the PD is invited to the meetings of the PESwithout being a member, while the Democrats are ‘allied’ with the Socialists in the EP. Inthe latter’s case, after membership in the European People’s Party (EPP) had been grantedin the late 1990s, both Silvio Berlusconi’s leadership and critical remarks towards the EU con-stituted an endless source of tension with the EPP (e.g., Martens 2009; Quaglia 2011).

Against this background, this article asks: are the Italian parties congruent with theiractual, or potential, political group in the EP? To what extent have they found their ‘home’in the EU? In order to address these questions in comparative perspective, the article relieson the EU Profiler data collected for the 2009 EP elections, comparing the congruence ofeach Italian party with its political group in the EP, and extending the comparison betweenItaly and the other member countries of the enlarged EU. Briefly anticipating here theresults of our analysis, we show that the Italian parties are, on average, surprisingly congruentwith their political group, and the Italian party system is unexpectedly matching the shape ofthe EP party system. Still, we remain cautious in the interpretation of these findings. Theendless Italian transition keeps the issue of the affiliation of the Italian parties in the EUopen. Equally important is, in the Italian case, the fact that congruence might be a contingent,rather than structural, outcome. As it is often the case for weakly institutionalised, or institutio-nalising, parties (e.g., Pridham 2005), transnational affiliation is a source of domestic legitimacy,and policy congruence becomes a function of pragmatic and opportunistic considerations.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. After presenting the Italian party system, andthe affiliation of its parties with the EP political groups (Section 2), we discuss the issue of policycongruence and its relevance for the debate on the EU democratic deficit (Section 3). Section 4develops the empirical analysis using the EU Profiler data. Finally, Section 5 discusses the impli-cations of the findings for political representation in the EU, and speculates on the significanceof congruence in the Italian case.

2. The Endless Transition of the Italian Parties and Party System

Notwithstanding the fragmentation and polarisation of the party system (Sartori 1966)since its establishment after the Second World War, Italy has traditionally been characterisedby the stability of the political parties in the electorate. Low figures of electoral volatility sus-tained for over four decades a highly structured party system (Morlino 2006). The stability ofpolitical parties at the national level coincided with the stability of partisan affiliation in the EP.

With the exception of the MSI, the ‘relevant’ parties of the pre-1994 Italian party system(DC, PSI, PSDI, PRI, PLI, PCI)2 affiliated with the traditional party families represented in the EP:Christian Democrats, Socialists, Liberals and Communists. These parties maintained a stableaffiliation with their EP groups from the first direct elections to the EP until 1994. As Table 1

232 EDOARDO BRESSANELLI AND DANIELA R. PICCIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

shows, only the MSI, the fringe parties Partito Radicale (PR), and Democrazia Proletaria (DP)changed their affiliation in the EP, while the newly established Lega Nord (LN) and theGreens entered the more recent Rainbow and Greens Groups.

This scenario drastically changed after 1994. As the consequence of a series of well-known, intertwined events taking place in the early 1990s at the institutional, judicial andsocietal levels—i.e., the adoption of a new electoral law; the ‘Clean Hands’ investigations,the exceptional turnover of the political parties in the Italian parliament, and the unprece-dented levels of electoral volatility—the Italian political landscape after the national politicalelections of 1994 appeared unrecognisable. The emergence of new successful parties, theorganisational and ideological reconfiguration of the traditional ones, and the frequent split-offs and mergers which have characterised the Italian party system ever since had obviousrepercussions also at the level of the EP. Overall, the changes of the Italian party systemafter 1994 have been so profound that little had remained in terms of the traditional partyfamilies characterising the country’s historical development since 1948. As the Christian Demo-crats, the Socialists, the small liberal parties and the Communists all virtually disappeared,where would the new and/or newly restructured parties sit in the EP?

Following the 1994 transformation of the party system and individual parties, two majorfeatures can be observed in relation to their affiliation with the EP political groups (see Table 2).First, the parties have frequently switched from one political group to the other. The mostextreme example is offered by the LN, which seated among the Rainbow Group (1989 –94),the Liberals (1994–97), the Non-Attached (1997–99), the Technical Group (1999–2004), theEurosceptics (2004 –06), the Conservative Group (2007–09), to join the Eurosceptics again inthe seventh parliament (2009 –14). Second, group affiliation in the EP has frequently beenthe object of internal dissent and contestation. When the Democratic Party (PD) formed in2007, for example, the two founding member parties, the former Communists (Democraticidi Sinistra, DS) and the former Christian Democrats (La Margherita), remained seated in two

TABLE 1Italian political parties in the EP in the Prima Repubblica (1979–94)

LegislaturesCOM / SOC / EPP / LD /

CDI DR ARCV /

NAGUE / PES EPP-ED LDR ALE

I: 1979–84 PCI PSI DC PLI DP n/a n/a n/a MSIPSDI PRI PR

II: 1984–89 PCI PSI DC PLI n/a MSI DP n/a PRPSDI PRI

III: 1989–94 PCI PSI DC PRI n/a n/a LN VERDI MSIPSDI

Key: COM: Communist and Allies Group (SF, Ind. Sin.)—from 1989, GUE: Group for the EuropeanUnited Left; SOC: Socialist Group—from 1984, PES: Group of the Party of European Socialists; EPP:Group of the European People’s Party (Christian-Democratic Group)—from 1989, EPP-ED: Groupof the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats; LD: Liberal andDemocratic Group—from 1984, LDR: Liberal and Democratic Reformist Group; CDI: Group forthe Technical Coordination and Defence of Indipendent Groups and Members; DR: Group of theEuropean Right—from 1984; ARC: Rainbow Group—from 1984; V : The Green Group in theEuropean Parliament—from 1989; NA: non-attached; n/a: not applicable.Source: www.europarl.europa.eu/.

FIT OR MISFIT? 233

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

TABLE 2Italian political parties in the EP in the Seconda Repubblica (1994–2014)

LegislaturesGUE -NGL

PES /S&D

EPP-ED /EPP

ELDR /ALDE

V -ALE

FORZAEUROPA ERA UEN

IND -DEM EFD NA

IV: 1994–1999 PRC PDS PPI LN VERDI FICCDUDC

ListaPannella(PR)

n/a n/a n/a AN

V: 1999–2004 PRC DS PPIFIUDEUR

DEM VERDI n/a n/a AN n/a n/a LNFIAMMALista Bonino(PR)

VI: 2004–2009 PRCPdCI

ULIVO-PD(ex-PDS)

FIUDEURUDC

ULIVO-PD(ex-PPI)IDV

VERDI n/a n/a ANLN

LN n/a FTASNPSI

VI: 2009–2014 – PD PDLUDC

IDV n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a LN LN

Key: GUE: Group of the European United Left from 1995: GUE-NGL: Group of the European United Left Nordic Green Left; PES: Group of the Party of European Socialistsfrom 2009: S&D: Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament; EPP-ED: Group of the European People’s Party (ChristianDemocrats) and European Democrats from 2009: EPP: Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats); ELDR: European Liberal Democrat and Reform Partyfrom 2004: ALDE: Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe; G: The Greens from 1999: G-EFA: The Greens European Free Alliance; ERA: European Radical Alliance;UEN: Union for Europe of the Nations; IND-DEM: Independence-Democracy Group; EFD: Europe of Freedom and Democracy; NA: Non-attached; n/a: Non applicable.

234

EDO

AR

DO

BR

ESSAN

ELLIA

ND

DA

NIELA

R.PIC

CIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

different EP groups. In 2009, the Christian Democratic faction, initially opposed to membershipin the Socialist group, accepted it in exchange for the change in the name of the EP group(from PES to Socialists and Democrats (S&D)). Equally contested was the affiliation of Silvio Ber-lusconi’s party Forza Italia (FI) into the EPP, which had been vetoed for several years by someChristian-Democratic members (Martens 2009: 140–7), and more recently that of Sinistra Eco-logia e Liberta’ (SEL), which included in the electoral symbol for the 2009 EP elections the logosof three (!) EP groups (PES, Greens and GUE).3

All in all, mapping the affiliation of the Italian parties with the political groups in the EP isall but a simple exercise. Changes in more established parties and the formation of new pol-itical parties are still ongoing after two decades of Seconda Repubblica, and the ‘impossibletransition’ (Morlino 2013) of Italy is clearly not over yet. In this light, Italy might well beregarded as a case where congruence between the national and the EP arenas is unlikely tobe found.

3. National Parties and Democratic Linkage in the EU

Congruence between the national and the EU parties and party systems is crucial for thefeasibility of a system of political representation in the EU. As Jacques Thomassen (2009: 13)put it, ‘the effectiveness’ of this latter ‘depends on its ability to aggregate and integratenational political agendas and the national cleavage structures at the European level’.

Under the dispositions of the Lisbon Treaty, European political parties received formalrecognition as representative agents, contributing ‘to forming European political awarenessand to expressing the will of citizens of the Union’ (art. 10.4). Yet, there is little dispute overthe fact that the Treaty’s ‘party article’ does not reflect the actual functioning of the processof political representation in the EU. Despite important changes implemented with thelatest rounds of Treaty revisions in the context of a ‘strategy of democratization’ of the EP(Cuesta Lopez 2010: 123), the representative process in the EU is still generally consideredas ‘poor’ (Mair and Thomassen 2010: 21) and the EP as an institution remote from the Europeancitizens. The second-order nature of the EP elections and the absence of a direct linkagebetween the electoral and the parliamentary arenas (e.g., Andeweg 1995; Reif and Schmitt1980) are traditionally regarded as insurmountable procedural obstacles for an effective demo-cratic linkage between the European citizens and their representatives in the EP.

Nonetheless, while acknowledging these limits, a growing field of research is now focus-ing on the potential for political representation in the EU through its political parties (Bardi et al.2011; McElroy and Benoit 2010, 2012). As Mair and Thomassen originally suggested (2010: 21),European elections and political parties may still serve as effective instruments of political rep-resentation even in the absence of a direct electoral linkage between the parliamentary andthe electoral arenas. If the political groups in the EP are successful in aggregating the politicalagendas that the national parties present to the national voters, then the ‘second-order’ natureof the EP elections appears less problematic as seen from the perspective of democraticlinkage.

In other words, it is the policy congruence between the national and the EU-level partiesthat would allow the latter to act as representative agents, despite the absence of a direct elec-toral linkage. Therefore, while the concept of congruence is normally used in the literature toevaluate the quality of the representative relationship between the citizens and the politicalelites (e.g., Miller and Stokes 1963; Schmitt and Thomassen 1999), we argue here that in themulti-level system of the EU congruence should be observed also between the national

FIT OR MISFIT? 235

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

parties and the EP party groups to which they affiliate. Consequently, the traditional definitionof policy congruence, ‘the similarity of opinions between party voters and party elites’ (Dalton2008: 227), is here adapted in order to capture ‘the similarity of opinions between nationalparties and their EP group’. As voters’ preferences are channelled to the EU level throughnational political parties, rather than being directly collected by the EU-level parties, thisfurther level of analysis is necessary to evaluate the potential for political representation inthe EU.

4. Empirical Analysis

The EU Profiler

To assess the policy congruence of the Italian parties in the EP groups, we make use ofthe EU Profiler data. The EU Profiler, the first Europe-wide ‘Voting Advice Application’, gener-ated uniquely comprehensive data on the political parties’ positions in all EU membercountries at the time of the 2009 EP elections (Trechsel and Mair 2011). Based on an extensivenetwork of collaborators coordinated by the European University Institute in Florence, itcollected data both on individual citizens—who responded to the EU Profiler onlinesurvey—and political parties in the (then) 27 member states of the EU and some candidatecountries.

Thus far, the EU Profiler data have been used to study the ideological cohesion anddifferences of the Europarties (e.g., Bressanelli 2013; Rose and Borz 2013), electoral competition(e.g., De Sio 2010) and methodological issues on the reliability and validity of their estimates(e.g., Louwerse and Rosema 2013; Wagner and Ruusuvirta 2011). Here, we make only use of theEU Profiler data on political parties. The positioning of the parties was the product of an orig-inal methodology, which combined different techniques. Parties (that is, people in the centraloffice) were first asked to self-place themselves. When they refused to do so, or their position-ing lacked sufficient face-validity, country experts were asked to make the coding in theirplace. In any case, this ‘expert’ judgment had to be always supported by the European orthe national manifesto of the party, by some programmatic statement in the party statuteor charter of values, or by declarations of the party leadership. To enhance consistencyamong the coders, sources were ranked and ordered hierarchically: the national manifestofor the 2009 EP elections came first, whereas declarations in the media were at the bottomof the list (Trechsel 2010).

In the Italian case, where political parties missed the chance to provide their ‘official’ pos-ition, country experts had to locate all parties in the policy space, on the bases of their mani-festos and other official documents presented ahead of the 2009 EP elections. Information wascollected for all those parties which, according to the pre-electoral opinion polls, had the tan-gible possibility to overcome the electoral threshold of 4% of the votes, elect representatives tothe parliament, and consequently join one of its political groups.4 The uncertainty that sur-rounded the electoral context and the delay in the preparation of the manifestos made thedata collection particularly challenging.5

As for the position of the political groups in the EP, instead, we rely on an indirect esti-mate. Thus, using the EU Profiler data, we calculated the mean of the positions of the nationalmember parties on the relevant policy dimensions (excluding, obviously, the Italian memberparties from the computation).6 Unfortunately, a direct measure of their positions, obtainedfrom the coding of the Euromanifestos, was not included in the final release of the EU Profiler

236 EDOARDO BRESSANELLI AND DANIELA R. PICCIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

data. As their election manifestos failed to provide sufficient information on several policystatements, the estimates were considered to be not sufficiently accurate.

Policy Congruence?

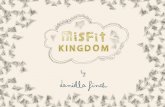

Taking advantage of the EU Profiler data, we first compare the policy positions of theItalian parties and the respective EP groups on the seven most salient policy dimensions ident-ified by the EU Profiler on the basis of a comparative analysis of party competition in Europe(Trechsel and Mair 2011): economic liberalism, restrictive financial policy, law and order, restric-tive immigration policy, environmental protection, expanded welfare state and liberal society.The spiders presented in Figure 1 graphically show the policy fit of the Italian parties in their EPgroup. Each spider displays the position on the seven dimensions of both the Italian and the EPparties. By comparing the areas obtained by interconnecting the policy positions, it is possibleto intuitively grasp whether the national parties are congruent with their EP group.

The spiders provide some interesting insights. Overall, a good level of congruence canbe observed for most combinations. Mainstream political parties—the centre-right PDL, thecentre-left PD and the centrist UDC—occupy an almost identical position to their EP group.More ideologically extreme parties (SEL) or electoral alliances (PdCI/RC) also appear to fittheir political group quite well. The poorest policy fit is for the LN and the Europe forFreedom and Democracy (EFD), and for the IdV and the Alliance of Liberals and Democratsfor Europe (ALDE).

Yet, a number of dimensions where parties diverge most with their political group can beidentified. Thus, Berlusconi’s party appears more inclined to impose stricter rules on immigra-tion and law and order measures, and is less supportive of liberal society and environmentalissues, than the EPP. On immigration and law and order, the LN is also tougher than its politicalgroup. On the other side of the policy spectrum, the PD appears to be more in favour ofenvironmental protection, and less keen on welfare policies, than the S&D. The PdCI/RC and,especially, SEL appear to be more in favour of libertarian and environmental issues thantheir transnational group. Finally, the IdV is more committed to welfare-state policies andenvironmental protection than the ALDE.

While most of the Italian parties, and certainly all mainstream parties, prima facie appearto fit their political group in the EP rather well, we need a comparative measure to more pre-cisely assess their level of congruence. We then calculated congruence, building on the exten-sive literature on the ‘proximity’ between parties (or legislators) and voters (see Stokes 1999 fora review), as the Euclidean distance7 between the national parties of the 27 member states ofthe EU and their political groups in 2009 on the two most important dimensions in the EPpolicy space: the left–right and the integration dimension (Hix et al. 2007). The dimensionsrange from -2 (respectively most left-wing and outright opposition to integration) to 2(respectively most right-wing and full support to integration). Hence, there is the greatest poss-ible congruence when the distance between a national party and the EP group to which it affili-ates equals 0.

Figure 2 shows the average level of congruence of the Italian parties in the politicalgroups, compared with the other 26 member countries of the EU. As it can be seen, the con-gruence of the Italian parties in the EP policy space is higher than the EU-27 average (0.63 and0.79, respectively), and is, moreover, almost identical to the level of congruence for Germany,whose party system is often described as having a similar format and mechanics to the EP partysystem (Hix et al. 2007: 26). While it does not come as a surprise to observe that the UK parties

FIT OR MISFIT? 237

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

FIGURE 1

Spider graphs of congruence of the Italian parties and their political group in the EP

238

EDO

AR

DO

BR

ESSAN

ELLIA

ND

DA

NIELA

R.PIC

CIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

FIGURE 1

Continued

FITO

RM

ISFIT?239

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

have the poorest fit in the political groups, it is worth stressing that their level of congruence(1.28) is more than twice as bad as the Italian one.

Finally, we compare the structure of competition in the EP and the Italian party systems(Figure 3). The EP party system, as traditionally observed (Hix and Lord 1997), is still mostappropriately described by an inverted-U curve. The mainstream groups—the EPP, the S&Dand the ALDE—located at the centre of the policy space, are also fervent supporters of inte-gration. Contrariwise, groups at the two extremes of the left–right dimension, such as theGUE-NGL and the EFD, are also strongly Eurosceptic. In the Italian party system, more criticalpositions towards the EU are also found at the extremes of the left–right spectrum (thePdCI/RC and, especially, the LN), while all mainstream parties support integration. This is

FIGURE 3

The EP and the Italian party systemsKey: Left panel: the EP party system; Right panel: the Italian party system

FIGURE 2

Congruence between national parties and political groups in the EP in the EU-27

240 EDOARDO BRESSANELLI AND DANIELA R. PICCIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

also, surprisingly, the case for Berlusconi’s party which, at least in the official party documents(the party statutes and its Charter of Values), embraces a clear pro-EU position (see furtherQuaglia 2011). Thus, in Italy as well as in the EP, the left–right and the integration dimensionare orthogonal to each other,8 and the inverted-U curve appears to be the most effective wayto describe the shape of the party system.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

The key findings of this article can be briefly summarised: we found good levels of policycongruence (above the EU-27 average) between the Italian parties and party system and theEP parties and party system. Our findings bear positive implications for political representationat the EU level: under the 2009–14 mandate the EU-level parties in the EP, albeit indirectly viathe national parties, did effectively represent the preferences of the Italian voters. Consideringthe complete transformation of the Italian parties and party system which followed the col-lapse of the Prima Repubblica, their lack of institutionalisation, their frequent switchesamong the EP political groups, we view this as an unexpected and theoretically challengingconclusion.

Indeed, our findings show how political representation of the national electorates maytake place even in a complex multi-level setting, and despite its alleged ‘democratic deficit’.Clearly, the national systems of political representation, where there is a direct linkagebetween voters and parties, may not be the only mechanism for effectively representing citi-zens. Especially in the light of the proposals aiming at reforming the system of functioning ofthe European level political parties,9 it may even be argued that an exclusive focus on thenational level is becoming increasingly irrelevant for judging how representation works inthe multi-level political system of the EU.

Yet, policy congruence between the national parties and the EP groups could well be theproduct of strategic, if not tactical, reasons. In other words, especially in a system where partiesare weakly institutionalised, there might be strong pragmatic incentives for the national partiesto converge policy positions with their EP groups. The political groups control the allocation ofinternal posts in the EP, and the national member parties get additional posts and resources toreward their members (Bressanelli 2012). Additionally, as it has been argued for the case ofEastern European countries (Hlousek and Kopecek 2010; Pridham 2005), in fluid and weaklyinstitutionalised party systems with relatively young parties, the EP political groups mayoffer policy ideas and an established set of reference values that their national counterpartsmay refer to. As seen in this light, policy congruence might be a more contingent, ratherthan structural, outcome.

Longitudinal data are needed to provide a diachronic perspective and verify whethercongruence between the Italian parties and their EP groups persists over time.10 To be sure,there are some reasons to be sceptical: since 2009, the Italian party system did all but stabilise.Which parties and electoral lists—in short, which ‘electoral supply’—will be offered to theItalian voters in forthcoming elections is all but clear. For the moment, however, whetherthese findings will extend beyond the 2009–14 EP remains a matter open to speculation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Both authors contributed equally to this article. However, section 2, ‘The Endless Transition of

the Italian Parties and Party System’, was written by Daniela R. Piccio.

FIT OR MISFIT? 241

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

NOTES

1. European Commission, ‘Preparing for the 2014 European elections: further enhancing their

democratic and efficient conduct’ (COM(2013) 126).

2. Following influential Sartori’s classification (1976) parties are ‘relevant’ if they hold either a

‘coalition’ or a ‘blackmail’ potential.

3. In January 2012, its party leader declared: ‘If I could, I would get three membership cards in

the EU: that of the European Left, which I have myself contributed to build up, that of the

Socialists, which today play an important role to change the continent, and that of the

Greens, which have understood some key changes before the other parties’ (Il Manifesto,

20.01.2012).

4. Thus, the parties are: Unione Democratici di Centro (UDC), Popolo delle Liberta’ (PDL), Partito

Democratico (PD), Italia dei Valori (IdV), Lega Nord (LN), Sinistra Ecologia e Liberta’ (SEL), and

the alliance between Partito dei Comunisti Italiani and Rifondazione Comunista (PdCI/RC).

5. The Italian team was composed by Andrea Calderaro, Furio Stamati and the authors of this

article.

6. The policy positions of the national parties were weighted for the number of parliamentary

seats they obtained in the 2009 EP elections. By weighting, we account for the fact that the

larger parties have more leverage in determining the policy positions of the EP groups and,

therefore, ‘matter more’ than the smaller member parties.

7. Policy distances are calculated as:p

[(pi – pj)2 + (qi – qj)

2] where p and q are the positions of

party i and group j on a given dimension. For an assessment of alternative methods used in

VAAs, see Louwerse and Rosema (2013).

8. The correlations among the two dimensions are -0.04 (EP); 0.06 (Italy), both not statistically

significant.

9. See MEP Giannakou Report on ‘European political parties and European political foun-

dations: statute and funding’ (2012/0237(COD)).

10. The EUandI project launched by the European University Institute in occasion of the 2014 EP

elections will provide this new set of data. See www.eui.eu/Projects/EUDO/EUandI/Index.aspx.

REFERENCES

ANDEWEG, R. B. 1995. The reshaping of national party systems. West European Politics 18(3): 58–78.

BARDI, L., E. BRESSANELLI, E. CALOSSI, W. GAGATEK, P. MAIR and E. PIZZIMENTI. 2011. How to Create a

Transnational Party System. Florence: European University Institute.

BRESSANELLI, E. 2012. National parties and group membership in the European Parliament: ideology or

pragmatism? Journal of European Public Policy 19 (5): 737–54.

BRESSANELLI, E. 2013. Competitive and coherent? Profiling the Europarties in the 2009 European

Parliament election. Journal of European Integration 35 (6): 653– 68.

BRUG, W. VAN DER and C. VAN DER EIJK. 2007. European Elections and Domestic Politics: Lessons from the

Past and Scenarios for the Future. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

CUESTA LOPEZ, V. 2010. The Lisbon Treaty’s provisions on democratic principles: a legal framework for

participatory democracy. European Public Law 16 (1): 123–38.

DALTON, R. J. 2008. Citizens Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democra-

cies. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

242 EDOARDO BRESSANELLI AND DANIELA R. PICCIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

DE SIO, L. 2010. Beyond ‘position’ and ‘valence’: a unified framework for the analysis of political issues.

EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2010/83.

HIX, S. and C. LORD. 1997. Political Parties in the European Union. London: Macmillan.

HIX, S., A. G. NOURY and G. ROLAND. 2007. Democratic Politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge and

New York: Cambridge University Press.

HLOUSEK, V. and L. KOPECEK. 2010. Origin, Ideology and Transformation of Political Parties: East-Central

and Western Europe Compared. Farnham, Surrey and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

LOUWERSE, T. and M. ROSEMA. 2013. The design effects of voting advice applications: comparing

methods of calculating matches. Acta Politica, doi: 10.1057/ap.2013.30.

MAIR, P. and J. J. THOMASSEN. 2010. Political representation and government in the European Union.

Journal of European Public Policy 17 (1): 20–35.

MARTENS, W. 2009. Europe: I Struggle, I Overcome. Brussels: Springer.

MCELROY, G. and K. BENOIT. 2010. Party policy and group affiliation in the European Parliament. British

Journal of Political Science 40: 377–98.

MCELROY, G. and K. BENOIT. 2012. Policy positioning in the European Parliament. European Union Politics

13 (1): 150–67.

MILLER, W. E. and D. E. STOKES. 1963. Constituency influence in Congress. The American Political Science

Review 57 (1): 45–56.

MORLINO, L. 2006. Le tre fasi dei partiti italiani. In Partiti e caso italiano, edited by L. Morlino and

M. Tarchi. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 105–44.

MORLINO, L. 2013. The impossible transition and the unstable new mix: Italy 1992– 2012. Comparative

European Politics 11: 337– 59.

PRIDHAM, G. 2005. Designing Democracy: EU Enlargement and Regime Change in Post-Communist

Europe. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

QUAGLIA, L. 2011. The ebb and flow of Euroscepticism in Italy. South European Society and Politics 16

(1): 31–50.

REIF, K. H. and H. SCHMITT. 1980. Nine-second order national elections – a conceptual framework for the

analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research 8 (1): 3–44.

ROSE, R. and G. BORZ. 2013. Aggregation and representation in European Parliament party groups.

West European Politics 36 (3): 474–97.

SARTORI, G. 1966. European political parties: the case of polarized pluralism. In Political Parties and

Political Development, edited by J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner. Princeton: Princeton University

Press, pp. 137–76.

SARTORI, G. 1976. Parties and Party Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SCHMITT, H. and J. J. THOMASSEN. 1999. Political Representation and Legitimacy in the European Union.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

STOKES, S. C. 1999. Political parties and democracy. Annual Review of Political Science 2: 243–67.

THOMASSEN, J. J. 2009. The Legitimacy of the European Union after Enlargement. Oxford: Oxford Univer-

sity Press.

TRECHSEL, A. H. 2010. EU-Profiler: positioning of the parties in the European Elections. Florence: Euro-

pean University Institute.

TRECHSEL A. H. and P. MAIR. 2011. When parties (also) position themselves: an introduction to the EU

Profiler. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 8 (1): 1–20.

WAGNER, M. and O. RUUSUVIRTA. 2011. Matching voters to parties: voting advise applications and

models of party choice. Acta Politica 47: 400–22.

FIT OR MISFIT? 243

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

Edoardo Bressanelli is Lecturer in European Politics at the Department of European and Inter-

national Studies, King’s College London. His research interests include political parties

and representation, policy-making in the EU and Italian politics. He is the author of Euro-

parties after Enlargement: Organization, Ideology and Competition (Palgrave Macmillan,

2014). He has published, among others, in Comparative Political Studies and the

Journal of European Public Policy. Email: [email protected]

Daniela R. Piccio received her PhD at the European University Institute of Florence. Since 2010

she has been a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at Leiden University, conducting

research and writing extensively on party regulation and comparative political finance.

Her work has appeared in South European Society and Politics and International Political

Science Review as well as in several edited book volumes. Her main research interests

include political parties, political representation, social movements and party (finance)

regulation. Email: [email protected]

244 EDOARDO BRESSANELLI AND DANIELA R. PICCIO

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

05:

39 1

2 N

ovem

ber

2014