Bergson and Cubism: A Reassessment

-

Upload

robert-mark -

Category

Documents

-

view

275 -

download

12

Transcript of Bergson and Cubism: A Reassessment

This article was downloaded by: [Stony Brook University]On: 15 October 2014, At: 15:33Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Art JournalPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcaj20

Bergson and Cubism: A ReassessmentRobert Mark AntliffPublished online: 02 Aug 2014.

To cite this article: Robert Mark Antliff (1988) Bergson and Cubism: A Reassessment, Art Journal, 47:4, 341-349

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043249.1988.10792430

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) containedin the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make norepresentations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of theContent. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, andare not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon andshould be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable forany losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use ofthe Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematicreproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Bergson and Cubism:A Reassessment

By Robert Mark Antliff

Fig. 1 Jean Metzinger, Le Goiaer, 1911, oil on cardboard, 293/4 x 27 %".Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

[A] polite little man in a lecturer'smorning coat took his stand beforeme and started to question meabout Cubism. The theoreticalpainters of the fourth dimensionwere at that time hoping that thephilosopher of intuition would provide the exegesis for their plasticideas. Bergson, the plastic, led megently towards the Giaconda'ssmile. Insidiously, I sidetrackedhim towards Creative Evolution. . . . It was during an intervalof silence that I caught hisconcentrated gaze. I

T he influence of the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941)

on Cubism has, like the Giaconda'ssmile, remained enigmatic. Much of theproblem in this regard is, I believe,summarized in the painter JacquesEmile Blanche's reminiscence of a portrait sitting with Bergson in 1912 quotedabove.' Bergson, to Blanche's mind, hada theory of art that differed markedlyfrom that of the Cubist movement. ForBlanche, Cubism's fourth-dimensionalunderpinnings could not be reconciledwith the intuitionist aesthetic of Bergson's approach to such images asLeonardo's Mona Lisa.

In my view, however, the theoreticalchasm presented by Blanche may bebridged through a critical reading ofAlbert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger'stext of 1912, Du Cubisme, I believe thatDu Cubisme was written with Bergsonin mind, for it is clear from Blanche'shitherto unnoticed statement not onlythat Bergson was interested in Cubismin 1912 but that the Cubists wereencouraging that interest during theperiod in which Metzinger and Gleizesformulated their essay. In fact, by June22, 1912, the critic Andre Salmon could

publicly record Bergson's tentativeagreement to write a preface to theSection d'or exhibition of 1912, "if hewas definitely won over by their ideals."3 The effort to so persuade Bergsonhad begun a year previously, with Sal-

rnon's declaration that the Symbolistcritic Trancrede de Visan, "who encounters [Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, and Leger] at the Vers et Proseparties[.] seems absolutely committedto present them to the illustrious meta-

Winter 1988 341

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

physician."4 In short, the first attemptsto align Cubist theory with Bergson'sideas were contemporaneous withGleizes's and Metzinger's initial assessment of their respective views in preparation for the writing of Du Cubisme?

Yet no sustained comparative examination of Cubism's precepts with thoseof Bergson has been undertaken thusfar." Attention has focused rather on theeffect of Bergson's literary interpreterson the Cubist movement. Jules Romains's poetic doctrine of unanimismand the related poetry of Rene Arcoshave been studied in this regard. Bothwriters were participants in the Abbayede Creteil, the short-lived socialist community (1906-7) that included AlbertGleizes among its members. Unanimisttheory held that the individual coulddirectly experience the thoughts of others and so obtain a collective consciousness. Intuition, defined by Bergson asthe ability immediately to discern ourown inner being as well as the thoughtsof others, is rightly associated withunanimism; in fact, one of Romains'searliest unanimist poems is entitledIntuitions.' Recently, the Cubist scholarChristopher Green has drawn attentionto Romains's later writings, such as theDeath of a Nobody (1911), and relatedthem to Bergson's ideas on memory.Romains's theories, Green argues, had avisual parallel in Cubist imagery after1911.8 In Green's view, the Cubistsbecame familiar with Bergson's notionof a temporal continuity connecting theremembered past to a dynamic presentthrough Romains. Cubist works such asLeger's Study for Three Figures ( 1911)are held by Green to employ multipleviewpoints and combine images fromdisparate temporal and spatial contextsto evoke Bergson's conception ofpsychological time, known as duration.

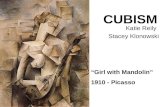

In effect, Green's argument echoes areading of Bergson first presented byChristopher Gray, who asserted that theamalgam of viewpoints in works such asMetzinger's Le Goiaer (Fig. 1), represents the artist's accumulated experience of the model over a period of time."Similar interpretations had been putforth by Roger Allard in 1910 and byJean Metzinger in 1911. 10 In DuCubisme Gleizes and Metzinger notethat "moving around an object to seizefrom it several successive appearances"enables the artist to "reconstitute it intime. "II Gleizes subsequently attributedthis theory to Metzinger, stating that inLe Goiaer it is possible to see "theconsequences of this movement [of theartist] introduced in an art that did notuntil that time include a plurality ofperspectives.?" For Gray, Cubist simultaneity is a reflection of an artist's psy-

chological experience, but for some proponents of a Kantian interpretation ofCubism these same multiple views arethe artist's conceptual means of grasping the thing-in-itself. According to thisKantian schema, the Puteaux Cubistsabandoned the optical representation ofan object by linear perspective in favorof a conceptual representation in whichmultiple views allow both artist andviewer to synthesize the object into asingle image of the thing as it is ratherthan as it appears." In short, we areconfronted with two conflicting views ofthe significance of simultaneity.

In analysing Du Cubisme I shallreconsider these two interpretations andtheir relation to Bergson's theories. Inaddition, I shall argue that Gleizes andMetzinger came to study Bergsonthrough the influence of Tancrede deVisan's writings on the Puteaux Cubists.According to Andre Salmon's statementof November 1911, it was Visan, notRomains or Arcos, who should introduce the Cubists to Bergson. Indeed, thechoice was a logical one: Visan was awell-known Symbolist poet, who hadbegun attending Bergson's lectures before 1904 and in whose Paysages lntrospectifs (1905) was the first extendeddiscussion of the theoretical parallels ofBergson's ideas and the Symbolistidiom." In 1911, Visan not only joinedGleizes in signing Henri-Martin Barzun's manifesto of simultaneity, L'Eredu Dramel? but also published his ownvolume of literary criticism, L'Attitudedu Lyrisme Contemporaine (1911).This volume, which drew together studies previously published in such magazines as Vers et Prose. was widely heralded as the definitive application ofBergson's theories to the study of Symbolist literary techniques." By correlating Visan's ideas with the aesthetic ofboth Cubism and Bergson, I hope tomake a case for Visan's crucial role asthe primary Bergsonian theorist withinCubist circles.

I n their effort to define Cubism as avanguard movement, the authors of

Du Cubisme distinguished the artist'sperceptual abilities from those of theaverage human being: "To discern aform" the public must "verify it by apre-existing idea, an act that no one savethe man we call an artist can accomplishwithout external assistance.'?" For thepublic it is art itself that aids in thediscernment of a form: "Before a natural spectacle, the child, in order to coordinate his sensations and subject them tomental control, compares them with hispicture-book; culture intervening, theadult refers himself to works of art. "18

This social application of a perceptual

theory of conventionalism in effect privileges the artist as the inventer of newvisual conventions to be taken up by adocile public. Docility, however, cansoon turn to hostility; although the workof art "forces the crowd ... to adopt thesame relationship [the artist] established with nature," this same crowd"long remains the slave of the paintedimage, and persists in seeing the worldonly through the adopted sign. That iswhy any new form seems monstrous,and why the most slavish imitations areadmired. "19

Having asserted the artist's vanguardposition as the arbiter of new visualconventions, Gleizes and Metzinger nowseek to explain how the artist goes aboutescaping from the tyranny of past pictorial conventions to behold nature anew.They update an old avant-garde doctrine that allies nonconventional seeingdirectly to the expression of one's personality: "To establish pictorial spacewe must have recourse to tactile andmotor sensations, indeed to all our faculties. It is our whole personality which,contracting or expanding, transformsthe plane of the picture." And elsewhere: "The art which ceases to be afixation of our personality (unmeasurable, in which nothing is ever reroeated)fails to do what we expect of it." 0

Since artists do not organize theirsensations by adopting the visual conventions established through artistic tradition, they must have recourse to theorganization of their own bodily sensations, defined in Du Cubisme as "tactileand motor sensations." As Linda Dalrymple Henderson has pointed out, theCubists, in referring to tactile and motorsensations, embraced the perceptualtheories of Henri Poincare, who proposed that our perception of space is theproduct of an internal coordination ofour various sensory faculties into a spatial gestalt we mistakenly identify asexternal to US.

21 Space is no longer anabsolute category of experience but arelative one-relative to our sensory faculties, and, secondarily, to culture's conventions of artistic representation. Sincethe artist does not rely on social conventions to arrive at a conception of space,the Cubists associate pictorial spacewith personal expression. Furthermore,a spatial gestalt synthesizes our intellectual faculty of organization with ourartistic sensitivity to sensations; theCubists, like Cezanne, master the "artof giving to our instinct a plastic consciousness.?" Spatial construction in aCubist painting is the product of theinterrelation of consciousness andfeeling.

For this reason Cubist space is areflection of the whole personality.

341 Art Journal

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

From the temporal point of view, aCubist painting should somehow embody the heterogeneous nature of one's"unmeasurable duration in which nothing is repeated.':" In achieving this end,the artist has "the power of renderingenormous that which we regard as minuscule and as infinitesimal that whichwe know to be considerable: he changesquantity into quality. "24 In Cubist theory, "qualitative" space is the pictorialanalog to temporal heterogeneity.

"Torn from natural space," theobjects represented in this manner"have entered a different kind of space,which does not assimilate the proportions observed. ,,25 Observed space, thespace of "science," is the product ofproportional measurement, whose pictorial analog is "traditional perspective. ,,26

Cubist space, as an imprint of the heterogenous personality, shares its "unmeasurable" quality. And for a spatialconstruction to reflect the personality,relations between objects in that spacemust be established in a qualitative,nonscientific manner. To apprehendspace qualitatively, the artist mustbecome acutely aware of his or herinstinctual and emotive response to sensation, which Gleizes and Metzingerrelate to the artist's faculty of discernment, or taste. The resulting dichotomysets scientific, quantitative space-identified with traditional perspectiveagainst an artistic, qualitative treatmentof space, which the Cubists associatewith the ordering of space in a nonquantifiable manner. The former spatialschema constitutes an impersonal, measurable medium estranged from its creator, whereas the latter qualitative projection is a synthetic expression of thewhole personality.

A similar dichotomy exists, in fact, inBergson's separation of intellec

tual, scientific modes of enquiry fromthe faculty of intuition, which he relatedto artistic perception and metaphysicalmodes of enquiry. Bergson's notion ofartistic intuition is discussed in CreativeEvolution (1907), but its roots are in thecritique of the intellectual treatment oftime found in his early book Time andFree Will (1889). According to Bergson, intellectual time-the conception oftime propagated within the naturalsciences-should not be confused withthe time we experience directly in ourdaily lives. The time of science is amathematical conception, symbolized asa unit of measure by our clocks andchronometers. In keeping with the quantitative nature of such measuring instruments, scientific time is represented asan extended, homogeneous medium,composed of normative units (years,

hours, seconds)." But these symbols orunits distort rather than reflect ourinner experience of time; they satisfy theimpersonal, practical conception of timethat regulates society, but are inadequate as symbols of our individual, feltexperience of time.

Psychologically, the intellect cannever comprehend movement or duration because its spatial models treatmovement as something complete; withregard to our own activity, we gain anintellectual perspective on it only in retrospect and, as such, any intellectual orlogical cognition of an act is itself aproduct of that act." This is because allaction entails a process of externalization, in which duration, with its interpenetrating moments, becomes spatialized into quantifiable instants eachexternal to the next. For example, a lineis a representation of a generative act, itis not the act itself."

Similarly, in Bergson's schema thereare other forms of self-representationthat, owing to their spatialized properties, fail to mirror our experience ofinner duration, which Bergson identifiesas cognition of the "profound self. ,,30

Words, for example, are spatial in orientation. Just as standardized mathematical units of time constitute impersonalrepresentations of our individual experience of time, so words such as "love" or"hate" are impersonal labels applicableto everyone regardless of the individualcharacter of our emotions. As impersonalized representations of the self, wordsare convenient counters adapted tosocial discourse; yet from the standpointof the personality experiencing the emotion, they are impoverished, generalizedsymbols." Yet the intellect is a facultyadapted to social life, and most of ouractivities are "intellectual" rather thandeeply expressive of our character. Onlythe artist is able to transcend socialconventions and give form to individualthoughts and feelings in all theirfreshness."

Bergson's critique of scientific andsocially conventional modes of selfrepresentation as unable to signify thepersonality corresponds to the Cubists'rejection of science and society in anattempt to capture the whole self in awork of art. Moreover, both Bergsonand the Cubists define this inner self asexisting in heterogeneous time, whichcannot be represented with "quantitative" signs. And for Bergson it is theartist who transcends social conventionsand obtains a direct cognition of his orher durational being.

H oW then do we grasp, let aloneexpress, this profound self? We

must begin by recognizing that the intel-

lect and its signs do not reflect the truenature of our inner being. Logic distortsthe self; mechanistic or deterministicinterpretations of durational experienceare the products of such distortion."And such interpretations fail to recognize the freedom inherent in any act thatis a product of the profound self: if "wepenetrate into the depths of the organized and living intelligence, we shallwitness the joining together or ratherthe blending of many ideas which, whenonce dissociated, seem to exclude oneanother as logically contradictoryterms. "34 Thus the novelist, by "tearingaside the cleverly woven curtain of ourconventional ego, shows us under thisappearance of logic a fundamentalabsurdity. ,,35

The free act, as a reflection of theprofound self, is at the same time bothconscious and deeply imbued with feeling. Expressive of the whole personality,it is what Bergson ultimately defined asan intuitive or artistic act." In order toact artistically, the Bergsonian artistmust first take up a sympathetic attitude with regard to his or her own being.Since intellectual modes of thinking andtheir signs afford only a superficialimage of the self, they must berejected-transcended-in favor of anempathetic but conscious relation toone's inner self. This act of sympathydemands a great deal of effort, for toempathize consciously with something isto go against the inteIlectual habits thatnormally dominate consciousness." Bytranscending the intellect's passive,fragmentary view of the self, one experiences the self in the process of selfcreating, that is, free activity." Thisdeep self is organic in nature, since it isfilled with interpenetrating thoughtsand feelings. Thus "ideas which wereceive ready-made" will remain external to the profound self, and "float onthe surface" of the mind "like deadleaves of the water of a pond.?" Furthermore, "As the self thus refracted,and thereby broken to pieces, is muchbetter adapted to the requirements ofsocial life in general and language inparticular, consciousness prefers it, andgradually loses sight of the fundamentalself.,,40 This social or predeterminedself is antithetical to the artistictemperament.

"The artist," therefore, "aims at giving us a share in this emotion, so rich, sopersonal, so novel, and at enabling us toexperience what he cannot make usunderstand. ,,4) But no sign in and ofitself can fully represent the artist'sinternal intuition, nor can it representthis immediate experience to others. Theartist can only suggest intuition throughthe medium of an art work, not repre-

Winter 1988 343

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

sent it. What then are the structuralprinciples operative in an art work thatenable such suggestion to take place?And finally, how can such precepts berelated to Du Cubisme?

T o begin with, for both Bergson andthe Puteaux Cubists, a work of art

is a projection of our conscious reactionto deep-seated feelings. Bergson distinguishes the felt or intuitive act from a"scientific" or nonemotive activity.Only the former is able to express thewhole self, which is by definition bothconscious and alogical. The Cubistsecho Bergson when they declare theirdesire to give "instinct" to their "plasticconsciousness." The scientific temperament cedes to the artistic state of mind,and measurement is no longer the guiding principle behind the spatial organization of a canvas. Instead, relationsbetween objects are established qualitativel~, that is, after the dictates of feeling." Linear perspective, being a mathematical system of representation, is tobe avoided.

Yet the conception of "qualitative"space outlined in Du Cubisme appearsat first glance to depart from Bergson,who is commonly held to have drawn asharp distinction between quantitativespace and qualitative time, with no roomfor intermediary conceptions." If spaceis intrinsically quantifiable, then theterm "qualitative" can only be appliedto psychological time, and no spatialmedium can reflect the mixture of feeling and thought in our psychologicalduration. Space, therefore, must be anintellectual and impersonal medium.Acknowledging this apparent divergence, Christopher Gray declared thatGleizes and Metzinger failed "to realizethat the problem of giving experience totheir sense of dynamism is not a problemto be solved in terms of symbols forspace." Dynamism, said Gray, "is aproblem that can only be solved by thedevelopment of symbols for change,which has as its roots the concepts oftime and duration which are such afundamental part of the philosophy ofBergson."44

But Bergson actually did envisage anintermediary state of mind in whichspace is felt, rather than conceptualizedrationally. In Time and Free Will. hewrote of an experience of spatial "extensity" quite apart from an apprehensionof quantitative properties. "We must,"he said, "distinguish between perceptionof extensity and the conception ofspace." For instance, it is arguable "thatspace is not so homogeneous for theanimal as for us, and that determinations of space or directions do notassume for it a purely geometrical

form." By experiencing space in a perceptual rather than conceptual manner,animals are able to grasp "extensity"directly as a feeling, say, of direction."There is no intellectual process interposed between extensity and feeling thatactively distorts both with its geometrical schemas.

Unfortunately, evolution has exaggerated man's intellectual capacities tothe point where consciousness is permeated by the tendency to geometrize."And it is in this context that the artist, asone who recovers felt experience, mayalso apprehend the qualitative properties of space. In Du Cubisme Gleizesand Metzinger claim to render pictorialspace qualitatively precisely because"all plastic qualities guarantee a built-inemotion," that is, they circumnavigatethe intellect." Thus extensity is nolonger treated quantitatively, andGleizes and Metzinger establish amethod of structuring their images inkeeping with the Bergsonian paradigm.

G iven this paradigm one must nowask how the painted medium

induces a state of immediacy or intuition in the beholder. For this is what isimplied by the definition in Du Cubismeof pictorial space as a "sensitive passagebetween two subjective spaces. "48 Cubist space puts the beholder in immediatecontact with the artist's personality,because "this plane reflects the personality back u~n the understanding of thespectator.'?' To maintain fidelity to theself, spatial scale is related to feeling,but we are now told that such adjustments somehow influence the beholder'scognitive reaction to a work. How thendoes the pictorial medium act on thebeholder, to assist him or her in experiencing it from the artist's point of view?How does the beholder gain an intuitionof the artist's state of mind through amode of self-representation?

Bergson regarded all forms of representation as distorted refractions of aprofound, ineffable self. Thus any formof signification can be only an indirectconduit to the artist's fundamental self,and all expressive mediums can only"suggest" an intuition, which is inexpressible." Likewise, since expression isitself a process of externalization, anoriginal intuition may become intellectualized. We may choose to translateour intuition into a painted image, butthe very act of doing so leads to thequelling of inner emotion. If an artistgoes so far as to structure an imageanalytically, even the capacity for suggestion will be annulled. The beholder inturn will have no access to an artist'sintuition because an analytically structured canvas deadens any emotional

response. In effect, the pamtmg is nolonger a sensitive passage between twosubjective spaces; it is a barrier to intersubjectivity. As Bergson stated, "fromintuition one can pass on to analysis, butnot from analysis to intuition. "51 If anintuition is to be suggested, the work ofart itself must induce an alogical state ofmind in the beholder.

Bergson addressed this issue by developing a theory that closely approximatesthe Cubist notions of simultaneity. Theorigin of this theory lies in his analysis ofthe perceptual image. Previously I mentioned Bergson's distinction between theperception of qualitative extensity andthe conceptualization of space; I nowwish to emphasize the relation he drewbetween pure perception and an immediate grasp of inner duration. Our psychological duration, Bergson stated, ismade up of unstable, fluctuant sensations, which constitute our felt impressions of the world. Through socialization, however, we affix labels or "words"to these immediate impressions. Theword that "stores up the stable, commonand consequently impersonal element inthe impressions of mankind ... overwhelms or at least covers over the delicate and fugitive impressions of ourindividual consciousness.t'" To namesomething is to conceptualize experience, and lose sight of the deep-feltimpression that sensations would otherwise evoke in our innermost being.

Thus the image, as a form of representation, is more conducive to selfexpression than the written word, and,by implication, painting is superior topoetry as an art form. If the poet is toexpress a felt intuition through language, he or she must conceptualizeimages before arriving at a pattern ofspeech; "The poet is he with whomfeelings develop into images, and theimages themselves into words. "53 Asreaders we convert these words backinto images, and "seeing these imagespass before our eyes we in our turnexperience the feeling which was, so tospeak, their emotional equivalent. ,,54

But our translation of words intoimages, and images into an originalartistic intuition, can occur only if suchverbal imagery provokes an alogical anddynamic state in the reader's mind. Inhis resolution of this problem, Bergsondeveloped a literary technique, whichTancrede de Visan would later refer toas the doctrine of "successive or accumulated images."?' This theory, firstdiscussed by Bergson in the "Introduction to Metaphysics" reads:

To him who is not capable of giving himself the intuition of theduration constitutive of his being,nothing will ever give it, neither

344 Art Journal

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

concepts, nor images. In thisregard the philosopher's sole aimshould be to start up a certaineffort which utilitarian habits ofmind tend, in most men, to discourage. Now the image has atleast the advantage of keeping usin the concrete. No image willreplace the intuition of the duration, but many different images,taken from quite different ordersof things, will be able, through theconvergence of their action, todirect consciousness to the precisepoint where there is a certain intuition to seize on. By choosingimages as dissimilar as possible,anyone of them will be preventedfrom usurping the place of theintuition it is instructed to callforth .... By seeing that in spite oftheir differences in aspect they alldemand of the mind the same kindof attention and, as it were, thesame degree of tension, one willgradually accustom consciousnessto a particular and definitelydetermined disposition, preciselythe one it will have to adapt to ...to produce the desired effort and,by itself, arrive at the intuition."

The importance of this section for ourunderstanding of simultaneity cannot beoverestimated. Bergson begins the passage by acknowledging that most of uscannot intuitively discern our profoundself-our consciousness is dominated bythe intellect's "utilitarian habits ofmind.'?" Words are well adapted tothese intellectural habits, but images arecloser to our immediate, or "concrete,"experience. Thus the image, as a literarytool, can draw us towards apprehensionof the inner self, for which it is theemotional equivalent. "No image willreplace the intuition of duration," butthese same images "can direct consciousness to a precise point where thereis a certain intuition to seize on."

To guide consciousness, the writerselects images that are as "similar aspossible"; they must bear no logicalrelation to each other. In this way themind can be drawn into a particularalogical disposition described as a kindof attention or degree of tension signaledby the emerging interrelation we posit toconnect these images. In grasping theirinterrelation "in spite of their differences," our mind has moved from anextensive or intellectual state to anintensive or intuitive one. Thus we arriveat the state of attentive tension thatcharacterized the original intuition underlying the images. Through the suggestive mechanism of these images thewriter has put us in the mental disposition we have come to define as intuition.

Fig. 2 Eugene Carriere, Portrait ofElise, 1901-2, oil on canvas. Collectionunknown.

Moreover, since we ourselves producedthe effort needed to transcend the intellect, our apprehension of a writer's intuition is itself an intuitive act that involvesour whole being. The philosophical text,as the product of an intuitive insight,persuades the reader to instigateanother creative act in kind, and thesetwo intuitions commingle in the condition of intersubjectivity. Paradoxically,the reader must arrive at an internalintuition before being able to graspimmediately the philosopher's profoundintentions.

This passage is devoted to philosophical intuition, but elsewhere Bergsonemploys a similar psychological modelin a discussion of the Mona Lisa." Herethe intuition to be apprehended takesthe form of Lenoardo's experience of hismodel, and the mechanism of suggestionis found in the arabesque distribution oflines on a canvas, which lead us "towarda virtual center located behind theimage."59 The beholder will seek behindthe lines "the movement the eye does notsee, behind the movement itself something even more secret, the originalintention, the fundamental aspiration ofthe person: a simple thought equivalentto all the indefinite richness of form andcolour.t''"

Both the writer's image and the artist's line can provoke an intuition-theimage, because of its alogical relation toother images, and the line, because of itsrhythmic effect on the beholder's subconscious." In both cases these mechanisms suggest rather than representintuition-they evoke a virtual center ofconvergence where the mind perceives apurely mental unity, Their means maydiffer, but the end sought by philosopherand artist is virtually synonymous.

I t is my opinion that the Cubist aesthetic of Gleizes and Metzinger was

informed by Bergson's methods forevoking intuitive states. These hadalready been outlined by Tancrede deVisan in a 1910 article on Bergson,which quoted in their entirety passages Ihave cited.62 For Visan, Bergson's pronouncements on artistic intuition findtheir parallel in the dissolving arabesquelines of a Carriere (Fig. 2), while themethod of accumulated images is captured in the poetry of the SymbolistMaurice Maeterlinck. Maeterlinck, weare told, "accumulates disparateimages, turning an original impressionover and over, a clever play of combinedanalogies, despite an apparent discord,with a mind to grasping this impressionin its total complexiiy.?"

By 1912, Gleizes and Metzinger wereconversant enough in such Bergsoniantheory to incorporate a conception ofviewer intuition into Du Cubisme. Having determined that portions of the canvas should be set in irregular relation toone another to ensure that the wholeremain immeasurable and qualitative,they go on to conclude: "in order thatthe spectator, ready to establish unityhimself, may apprehend all the elementsin the order assigned to them by creativeintuition, the properties of each portionmust be left independent, and the plasticcontinuity must be broken up into athousand surprises of light and shade.?"Thus the Cubist breaks up the canvas'sunity in such a way as to allow thespectator's own "creative intuition" to"establish unity," and so discover thepainter's integral and intuitive conception. The organic, unified element ofthe canvas is ascertained through a mental process wherein the beholder is led"little by little toward the imaginativedepths where burns the light of organization.?" Unity resides not in the workof art but in the mind of the beholder.

To provoke an intuitive response, theplastic elements of the canvas must firstarouse the viewer's emotions. "Thediversity of relations of line to line mustbe indefinite; on this condition it incorporates quality, the immeasurable sumof the affinities perceived between thatwhich we discern and that whichalready existed within us; on this condition a work of art moves US."66 Thequalitative organization of the canvasnot only reflects the artist's pesonalitybut triggers an internal emotive response in the viewer. Similarly, to capture an intuitive rather than analyticalsensation of "fullness" the Cubists useCezanne's technique of passage to evokean apprehension of "the dynamism offorrn.?" "Between sculpturally boldreliefs, let us throw slender shafts which

Winter 1988 345

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

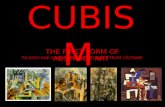

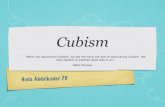

Fig. 3 Albert Gleizes, Bridges ofParis. 1912, oil on canvas, 223/ 4 x 28 1/t . Vienna,Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts.

do not define, but which suggest. Certain forms must remain implicit, so thatthe mind of the spectator is the chosenplace of their concrete birth.?"

The dynamism of form is thusdirectly related to the beholder's psychological reaction to a given work. Thisreaction, following the tenets of DuCubisme, leads us to see dynamic formas an expression of the profound self. Byconnecting terms such as quality andheterogeneity to the division of the canvas into unmeasurable rhythmic patterns, we discern the nonquantifiableand thus dynamic quality of volumetricspace. Furthermore, the two words "dynamism" and "form" exemplify a Bergsonian combination of images that logicor common sense would declare mutually exclusive." Dynamism calls tomind movement, yet form evokes theimage of stasis, and dynamism of form,the image of an unchanging object moving through space. In Du Cubisme, however, dynamic form constitutes a Cezannean type of spatial extensity unrelatedto the division of space into boundedobjects. Gleizes's Bridges of Paris (Fig.3), which was illustrated in DuCubisme, embodies this type of amorphous space. In the painting, a multiplicity of views are transversed by transparent shards that both overlay andinterconnect the underlying imagery.Objects portrayed (for instance, the twohouses in the bottom left) frequentlydissolve into abstract planes, causingour attention to fluctuate from the dis-

cernment of representational content tononrepresentational volume. It is therhythmic interrelation of such volumesthat instigates our intuitive apprehension of. the painting's organizationalmatrix.

As for the imagery couched in thisqualitative space, according to Gleizesand Metzinger, it should be as disparateas possible, "with a view to a qualitativepossession of the world":

Without using any allegorical orsymbolic literary artifice, but withonly inflections of lines and colors,a painter can show in the samepicture both a Chinese and aFrench city, together with themountains, oceans, flora and fauna, peoples with their histories anddesires, everything which in exterior reality separates them. Distance or time, concrete thing orpure conception, nothing refusesto be said in the painter'stongue."

Cubist imagery is not derived solelyfrom observation of the exterior world; itemerges out of the durational flux ofconsciousness. The selection of suchimagery is governed by subjective criteria such as "taste" and "sensitivity,"both of which are subordinate to will, forartistic will alone can "develop tastealong a plane parallel to that of the consciousness.?" Creative intuition, as hasbeen noted, entails a willed effort totranscend logical patterns of thought;

these disparate images, whose interrelation is determined subjectively, echothat transcendence.

T he Cubist conception of pictorialsimultaneity may have its roots in

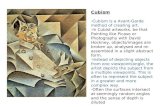

Futurist theory as well as in Visan'sBergsonian criticism. If the Cubistssought a pictorial precedent for suchimagery, they had only to consult GinoSeverini's Travel Memories (Fig. 4). Byhis own acknowledgment, Severinipainted this image in response to hisreading of Bergson's "Introduction toMetaphysics," and as a member of PaulFort's Vers et Prose circle, he was ~rob

ably familiar with Visan as well.' Forthis painting, Severini selected a vastarray of memory inages related to-traveland distributed them around a centralimage of a well, taken from his hometown." In Bergsonian and Cubist terms,the work is a paradigmatic example ofsimultaneity: the scale of these imagesdefies "perspectival" logic, they are disparate, yet bear a thematic relation toone another, and their radial arrangement suggests the idea of "convergence."

To arrive at his conception, Severinihad an intuition of the idea of travel, andsince Bergson equated consciousnesswith memory, his internal meditation onthe theme resulted in the welling up ofan array of remembered images, bearing a synthetic relation to the intuitionof travel.

Cubist works such as Delaunay's Eiffel Tower (Fig. 5) also combine disparate memory images in the depiction ofa single theme, and thus also have aBergsonian and unanimist genealogy."Aside from entering into intuitive relation to the self, a unanimist's primarygoal is to enter into intuitive correspondence with others." In fact, by organizing their canvases in such a way as toprovoke an intuition in the beholder'smind, the Puteaux Cubists probablyhoped to give the public some means ofentering into La Vie Unanime. Thus theCubists developed the artistic means ofachieving Romains's political ends,since the latter used his intuitive insightsto exalt the notion of collective consciousness. A poem such as Romains'sIntuitions is a utopian ode to the possibility of collective consciousness, andwith it, collective fraternity.

The earliest examples of unanimistinformed Cubist criticism are datable toabout 1910, with Metzinger's interpretation of Delaunay's Tower paintings."In a year that witnessed Romains'sdeclaration that Bergsonism could bethe predominant philosophy of the period, Metzinger describes Delaunay's Eiffel Tower image as an intuitive amal-

346 Art Journal

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

rather than intellectual means of representing the self. It is the self they willgrasp absolutely, not an object in space.

What holds true for the artist's selfimage is also pertinent to the beholder'sdurational experience of simultaneity.And again, Bergsonism is confused withKantian theory. For example, EdwardFry interprets Roger Allard's 1910 reference to the Cubist portrayal of multiple viewpoints as suggesting that "theviewer can reconstitute the fragmentedelements in the painting and thus arriveat a full comprehension of the originalobject. ,,85 He then associates this idea of"mental unity" with the Kantian notionof synthesis as well as with Kahnweiler'stheories." But the connections that linkCubism's "discursive" imagery, dynamic form, and the alogical means ofprovoking an intuition in the beholder'smind establish an alternative means ofarriving at "mental unity." The "thing"to be grasped is not an object, but a stateof mind.

The development of this theory hadprofound consequences within theavant-garde: the Futurist desire to placethe spectator in the center of the pictureand Malevich's creation of an alogisticaesthetic can be interrelated on the basisof these premises." I would agree withJohn Nash that the primary concern ofo« Cubisme is with the distinctive psychological makeup of the artist;" but Iwould temper his strict association ofGleizes and Metzinger's statementsconcerning artistic will with a Nietzschean notion of the will to power.Although the Nietzschean outlook iscompatible with the model of perceptual

nealogy included a literary interpretation of Bergson closely allied to the ideaof simultaneity.

Our ideas on what "simultaneity"entailed have also taken on greater complexity. On the whole, scholars havetended to follow the example of Christopher Gray, who connected simultaneityto the cinematographic conglomerationof images Bergson associated with ourintellectual perception of an object."Gray also regarded the Cubist correlation of dynamism with form as problematic. because, in his view, Bergson drewa radical distinction between space andtime. But it is precisely this associationof dynamism with form which constitutes an intuitive and Bergsonianconception of simultaneity.

Although Gray's correlation of duration with the portrayal of successiveviews of an object surely had currency inCubist criticism in 1911,83 by 1912 itwas embedded in an interpretation ofhow pictorial structure should reflect anintuitive grasp of the self. In DuCubisme the combination of such viewsis part of a mode of self-representationrather than a means of representing anautonomous object. Scholars who interpret such multiple views as entailing aKantian desire to represent the thingin-itself. misinterpret the Cubist notionof immediacy. They shift our focus fromstatements on the assimilation of objectsinto perceptual duration to a concernwith the portrayal of objects as objects,quite apart from the Cubist dialogue onconsciousness." In fact, the Cubistsrejected single-vanishing-point perspective in order to develop an intuitive

,:.,~l):lt~-tJ.

'JII"''',,t-'

I,'Fig. " Gino Severini. Travel Memories, 1911, oil on canvas. Collection unknown.

gam of the public's thoughts about thisicon of modernism: "Intuitive, Delaunayhas defined intuition as the brusquedeflagration of all the reasonings accumulated each day. ,,77 Like Severini,Delaunay is known to have painted thework from memory. but in this case thememory images themselves are purportedly collective and therefore unanimist in nature."

I n contrast to Jacques EmileBlanche's observation quoted at the

beginning of this article, Bergson's theory of art, including his interpretation ofthe Mona Lisa. was integral to theCubist aesthetic of Gleizes and Metzinger by 1912. This is an important point,because some Cubist scholars such asGeorge Beck and Mark Roskill havedismissed Bergson's aesthetic as superfluous to the Cubist project." Yet ifGleizes, Metzinger, and their Puteauxcolleagues were attempting to win overBergson in 1912, it would only makesense that they would acquaint themselves with the philosopher's aesthetictheories.

Indeed, such cognizance extendedbeyond pictorial theory as such toencompass a literary theory that Visanhad incorporated into a notion of simultaneity. Visan's Abbaye de Creteil contacts within the Vers et Prose groupmade him the ideal spokesperson forBergsonism within both Cubist andFuturist circles." What I wish toemphasize here-and Marinetti's ownership of Visan's Paysages lntrospectifs(1904) underscores the point 81-is thatthe Cubists' and Futurists' shared ge-

~k'~! ..!':~~/,;.

~;..:-:;;.7'.\ .~:

Winter 1988 347

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

conventionalism Gleizes and Metzingeradopted from Poincare, it cannotaccount for the discussion in DuCubisme of the artistic means of individual expression. Given Gleizes and Metzinger's subtle adaptation of Bergson'sconception of how the artist willfullytranscends the intellect to attain accessto the alogical, deep self, we must question Nash's supposition that referencesto will and taste in that text are invariably Nietzschean in import.

This version of Bergsonism alsooffered an alternative to a Nietzscheanform of individualism, inasmuch as itgave the artist a social mandate, that ofconverting the beholder into a creativeindividual. Thus the Bergsonian notionof simultaneity presented in Du Cubisme is yet another manifestation of theutopian aspirations that pervade theearly modernist conception of the artist's role in society."

NotesThis paper is dedicated to Rosemarie Bergman,upon her retirement, and to the memory of the lateWinthrop Judkins. I should like to thank MatthewAffron, Elisabeth Fraser, Patricia Leighten, Richard Shiff, and Votjech Jirat- Wasiutynski for critical reading. My conversations with Linda Henderson were particularly helpful in enriching myunderstanding of Du Cubisme.

I Jacques Emile Blanche, Portraits of a Lifetime. New York, 1938, pp. 244-45.

2 lbid., p. 244. Blanche does not give exact datesfor these sittings, but dates his commission topaint Bergson to the time of his London lectures of 1911.

3 Andre Salmon, "La Section d'or," Gil Bias(June 22, 1912).

4 Andre Salmon, "Bergson et les Cubistes," Paris-Journal (November 29, 1911): "qui recontreces messieurs {Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, and Leger] aux soirees de Vas et Prosesemble tout designe pour les presentre ii I'illustre metaphysicien."

5 Sec: Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs. Le Cubisme1908-14. Cahiers Albert Gleizes I. Lyons,1957, pp. 23-25.

6 For discussion of Bergson's impact on Cubism,see: Ivor Davies, "Western European ArtForms Influenced by Nietzsche and BergsonBefore 1914, Particularly Italian Futurism andFrench Orphism," Art International. 19:3(March 1975), pp. 49-55; George Beck,"Movement and Reality: Bergson and Cubism," The Structuralist. 15/16 (1975-76),pp. 109-16; and Timothy Mitchell, "Bergson,Le Bon, and Hermetic Cubism," Journal ofAesthetics and Art Criticism. 34 (Winter1977), pp. 175-84. For an analysis of Bergson'simpact on Kupke and Delaunay, sec: VirginiaSpate, Orphism, Oxford, 1979. Sherry Buckberrough's recent work on Delaunay includesan analysis of how Bergsonism may have led tothe proliferation of "circular" imagery in theart of the Futurists, Dupka, Delaunay, and

others; sec: Sherry A. Buckberrough, RobertDelaunay: The Discovery of Simultaneity.Ann Arbor, 1982.

7 Jules Remains, "Intuitions," La Phalange. I(July-December 1906), p. 175. In a shortreview of George Perin's La Lisiere Blondes.Remains states that Perin's notion of the soulclosely resembles Bergson's ideas concerningpsychological duration, thus dating Rornains'sfamiliarity with Bergson to 1906 or earlier; sec:Jules Remains, "Poesie.' ibid., pp. 463-64.Marie-Louise Bidal, Les j;crivains de L'Abbaye. Paris, 1939, contains a section on Bergson's influence on Romains and others associated with the Abbaye de Creteil.

8 Christopher Green, Leger and the AvantGarde. New Haven, 1976, p. 27, n. 49.

9 Christopher Gray, Cubist Aesthetic Theories.Baltimore, 1957, p. 87.

10 Roger Allard, "Au Salon D'Autornne de Paris," L'Art Libre (November 1910), p. 442; JeanMetzinger, "Cubisrne et Tradition," ParisJournal (August 16, 1911). Both articles arctranslated in Edward Fry, Cubism. London,1966,pp.62,66-67.

II Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger. DuCubisme, Paris, 1912; English translation inModern Artists on Art. cd. Robert L. Herbert,New York, 1964, p. 15. Herbert's translation isused throughout this essay.

12 Gleizes (cited n. 5), p. 24; English translationin Daniel Robbins, "Jean Metzinger at theCenter of Cubism," Jean Metzinger in Retrospect. exh. cat., Iowa City, The Iowa Museumof Art, 1985, p. 20.

13 Sec, for instance: Lynn Gamwell, Cubist Criticism. Ann Arbor, 1980, pp. 103, 106.

14 For a discussion of Visan, sec: Kenneth Cornell,The Post Symbolist Period. New Haven, 1958,pp.73-76.

15 Daniel Robbins, "From Symbolism to Cubism:The Abbaye de Creteil,' Art Journal. 23:2(Winter 1963-64), n. 36, p. 115.

16 Sec, for example: Louis Maudin, "Tancrede deVisan.' Vers et Prose. 26 (May-June 1911),pp. 210-13. Alexander Mercereau singles outYisan's book for special mention in La l.itterature et les Idees Nouvelles. Paris, 1912,pp.34-35.

17 Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. II), p. 6.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid., pp. 8, 12.

21 Linda Dalrymple Henderson, The FourthDimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry inModern Art. Princeton, 1983, pp. 82-89.

22 Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. II), p. 4.

23 Ibid., p. 12.

24 Ibid., p. 7.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid., pp. 7, 13.

27 Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will. trans.F. L. Pogson, New York, 1910 (rpt. 1960),pp. 107-11,194-96.

28 Ibid., pp. 47-49, 237.

29 Bergson (cited n. 27), pp. 102-4.

30 Ibid., pp. 6-11,128-39.

31 Ibid., pp. 132-34.

32 Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution. trans.Arthur Mitchell, New York, 1911 (rpt. 1938),pp. 176-77.

33 Bergson (cited n. 27), pp. 119-21; idem (citedn. 32), pp. ix-xv,

34 Bergson (cited n. 27), p. 136.

35 Ibid., p. 133.

36 Bergson (cited n. 32), pp. 6-7.

37 Ibid., pp. 342-43.

38 Ibid., p. 7.

39 Bergson (cited n. 27), p. 135.

40 Ibid., p. 128.

41 Ibid., p. 18.

42 Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. II), p. 4.

43 Readers of Bergson should be alert to thedistinction he makes between homogeneity andextensity, which is found in all his major texts.

44 Gray (cited n. 9), p. 86.

45 Bergson (cited n. 27), p. 96.

46 Bergson (cited n. 32), pp. 211-13.

47 Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. 11), p. 14.

48 Ibid., p. 8.

49 Ibid.

50 Bergson (cited n. 27), pp. 16-17.

51 Henri Bergson, "The Introduction to Metaphysics" (1903), in The Creative Mind. trans.Mabelle L. Andison, New York, 1946, p. 213.

52 Bergson (cited in 27), p. 132.

53 Ibid., p. 15.

54 Ibid.

55 Visan applied this concept to the poetry ofMaeterlinck in 1907, and later codified it in anarticle on Bergson published in 1910; see:Tancrede de Visan, "Sur L'Oeuvre de MauriceMaeterlinck,' Vas et Prose. 8 (December1906-February 1907), p. 92; and idem, "LaPhilosoplie de M. Bergson et le Lyrisme Contemporain,' Vers et Prose. 21 (April-June1910), p. 137.

56 Bergson (cited n. 51), p. 195.

57 Ibid.

58 Henri Bergson, "The Life and Work of FelixRavaisson" (1904), in The Creative Mind(cited n. 51), pp. 261-300.

59 Ibid., p. 273.

60 Ibid.

61 Bergson (cited n. 27), p. 13.

348 Art Journal

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4

62 Visan 1910 (cited n. 55), pp. 131,137.

63 Visan 1906-7 (cited n. 55), p. 92: "accumuleles images disparate, tourne et retourne uneimpression primitive, un jeu savant d'analogiescombinees, rnalgre un apparent discord, en vued'enserrer cette impression dans son entierecornplexite."

64 Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. II), p. 12.

65 Ibid., p. 5.

66 Ibid., p. 9.

67 Ibid., p. 8.

68 Ibid., p. 9.

69 Bergson (cited n. 51), pp. 208 -20.

70 Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. II), p. 17.

71 Ibid., pp. 16-17.

72 See: Denys Sutton, "The Singularity of Severini," Apollo. 97 (May 1973), pp. 450-51;Gino Severini, La Vita di Pittore, Milan, 1965,pp.83-97. For Severini's visit to AlbertGlcizes's studio in 1911, see: Albert Gleizes. ed.Jean Cassou, Lyons, 1954, pp. 19-20.

73 Marianne Martin, Futurist Art and Theory,Oxford, 1968. pp. 98-99.

74 On the Futurist relation to unanimism, see:Marianne Martin, "Futurism. Unanimism,and Apollinaire," Art Journal, 28:1 (Spring1969), pp. 258-68. Daniel Robbins has showntlie pervasive impact of unanimism on Gleizes,Le Fauconnier, and other Cubists in his variouspublications; in particular. see: Daniel Robbins, "The Formation and Maturity of AlbertGleizes: A Biographical and Critical Study,188 I through 1920" (Ph.D. diss., New YorkUniversity, 1975).

75 Jules Romains, "Intuitions" (cited in n. 7), p.175.

76 Jean Metzinger, "Notes sur la Peinture,' Pan.10 (October-November 1910), pp. 649-52.

77 Jules Romains, "Sur quelque rapports de laphilosophie et de l'Epoque,' La Grande Revue(August 10, 1910), p. 619; Metzinger (citedn. 76), p. 651. The English translation is byDaniel Robbins, who has recently drawn attention to Metzinger's discussion of Delaunay andLe Fauconnier in the 1910 Pan article; see:Robbins(citedn. 12).p. 10.

78 Delaunay attended Alexander Mercereau'ssoirees as of 1910, and may have becomeacquainted with unanimism there, before hemet Romains in January 1912. Although Met-

zinger relates Delaunay's Tower image to theunanimist intuitive method, Delaunay's artisticprocess was similar to Severini's introspectivetechnique. He apparently painted the image asit unfolded in his memory during the summerof 1910. Thus the Tower is a composite ofmemory images whose fragmentary arrangement evokes their durational origin. See: Buckberrough (cited n. 6), pp. 54. 59,91.

79 See: Beck (cited n. 6), p. Ill; and Roskill, TheInterpretation of Cubism, Philadelphia, 1985,p.35.

80 See: Daniel Robbins, "Sources of Cubism andFuturism," Art Journal, 41:4 (Winter 1981),pp.324-27.

81 A copy of this volume, which contains Visan'sfirst essay on Bergson and Symbolism, is in theMarinetti archive at the Beinecke library. YaleUniversity.

82 Gray (cited n. 9), p. 87.

83 See: Jean Metzinger, "Cubisme et Tradition,"Paris-Journal (August 16, 1911), Englishtranslation in Fry (cited n. 10), pp. 66-67.

R4 For a recent summation of the literature onKant and Cubism, see: Paul Crowther, "Cubism, Kant, and Ideology," Word and Image.3:2 (April-June 1987). pp. 195-201. For areference to Kantianism in Du Cubisme, see:Gleizes and Metzinger (cited n. II), p. 13.Gleizes and Metzinger explicitly refuted thepossibility of grasping an object absolutelythrough a combination of simultaneous views.

85 Fry (cited n. 10), p. 63.

86 Ibid.

87 On Futurism. see: Buckberrough (cited n. 6),pp. 136-39. For Bergson's effect on Malevich,see: Charlotte Douglas. Swans of OtherWorlds, Ann Arbor. 1980, pp. 49-61.

88 J. M. Nash, "The Nature of Cubism: A Studyof Conflicting Explanations,' Art History, 3:4(December, 1980), pp. 436-47. I wish to thankDaniel Robbins for drawing my attention toNash's article.

89 See: Rose-Carol Washton Long, "Occultism,Anarchism, and Abstraction: Kandinsky's Artof the Future," Art Journal, 46: I (Spring1987), pp. 38-45. For a discussion of the linksconnecting anarchism to the theories of artisticindividualism in France, see: Patricia DeeLeighten, "Picasso: Anarchism and Art, 18971914" (Ph.D. diss., The State Univesity of NewJersey, 1983).

Robert Mark Antliff is a Ph,D,candidate at Yale University and therecipient ofa Mary David Fellowshipfor /988-90. He is currently writinghis dissertation on the subject ofHenriBergson's influence on the visual artsbefore World War I.

Winter 1988 349

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ston

y B

rook

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

5:33

15

Oct

ober

201

4