Aj Gp Family Care Giving

Transcript of Aj Gp Family Care Giving

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

1/10

CLINICAL REVIEW

240 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004

Family Caregiving of Persons With Dementia

Prevalence, Health Effects, and Support Strategies

Richard Schulz, Ph.D.

Lynn M. Martire, Ph.D.

The authors summarize the dementia caregiving literature and provide recommen-

dations regarding practice guidelines for health professionals working with caregivers.

Family caregiving of older persons with disability has become commonplace in the

United States because of increases in life expectancy and the aging of the population,with resulting higher prevalence of chronic diseases and associated disabilities, in-

creased constraints in healthcare reimbursement, and advances in medical technol-

ogy. As a result, family members are increasingly being asked to perform complex

tasks similar to those carried out by paid health or social service providers, often at

great cost to their own well-being and great benefit to their relatives and society as a

whole. The public health significance of caregiving has spawned an extensive litera-

ture in this area, much of it focused on dementia caregiving because of the unique

and extreme challenges associated with caring for someone with cognitive impair-

ment. This article summarizes the literature on dementia caregiving, identifies key

issues and major findings regarding the definition and prevalence of caregiving, de-

scribes the psychiatric and physical health effects of caregiving, and reviews various

intervention approaches to improving caregiver burden, depression, and quality of

life. Authors review practice guidelines and recommendations for healthcare providers

in light of the empirical literature on family caregiving. (Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;

12:240–249)

Received March 7, 2003; revised September 24, 2003; accepted October 28, 2004. From the University Center for Social and Urban Research,

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. Send correspondence to Richard Schultz, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry, Director, University Center for

Social and Urban Research, University of Pittsburgh, 121 University Place, 6th Floor, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. e-mail: [email protected]

2004 American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry

Millions of Americans provide help to disabled

elderly family members living in the commu-

nity, sometimes at great cost to themselves and great

benefit to their relatives and society as a whole. Al-

though no standard definition of family caregiving

exists, there is general consensus that it involves the

provision of extraordinary care, exceeding the

bounds of what is normative or usual in family re-

lationships. Caregiving typically involves a signifi-

cant expenditure of time, energy, and money over po-

tentially long periods of time; it involves tasks that

may be unpleasant and uncomfortable and are psy-

chologically stressful and physically exhausting.

A broadly inclusive definition that characterizes

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

2/10

Schultz and Martire

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004 241

caregiving in terms of providing “informal” care to

an ill or disabled family member or friend of any age

yields estimates of approximately 52 million caregiv-

ers annually in the United States.1 A more restrictive

definition, which requires the provision of care to

someone with long-term illness or disability, yields aconsiderably lower estimate of approximately 9.4

million.2 Limiting care-recipient age range to 65 and

older further reduces the estimates to approximately

5.9 to 7 million.1,3 Of the approximately 3 million

Americans with Alzheimer disease (AD) living at

home, it is estimated that 75% of the home care is

provided directly by family and friends, and the re-

maining 25% represents services purchased by family

members. Regardless of which of these numbers we

select, caregiving is clearly a public health issue of

national significance, and one that will become more

prominent with the aging of the baby boomers.

Caregiving is not a new phenomenon. Before the

enactment of Social Security and Medicare, family

members were the primary and often only source of

support for disabled elderly people. What has

changed in the last half-century is the number of in-

dividuals involved in caregiving, the duration of the

caregiving role, and the types of caregiving tasks per-

formed. Because of increases in life expectancy and

the aging of the population, the shift from acute to

chronic diseases and their associated disabilities,

changes in healthcare reimbursement, and advancesin medical technology, caregiving has become com-

monplace. For some individuals, the caregiving role

lasts many years, even decades, and caregivers are

increasingly being asked to perform complex tasks

similar to those carried out by paid health or social

service providers.

The dominant conceptual model for caregiving as-

sumes that the onset and progression of chronic ill-

ness and functional decline is stressful for both pa-

tient and caregiver and, as such, can be studied

within the framework of traditional stress/health

models. Indeed, some researchers have likened care-giving to being exposed to a severe, long-term,

chronic stressor. Within this framework, objective

stressors include measures of patient physical dis-

ability, cognitive impairment, and problem behav-

iors, as well as the type and intensity of caregiving

provided. The effects of caregiving are typically mea-

sured in terms of psychological distress and burden

and psychiatric and physical morbidity, as well as in

economic impacts such reduced work-hours or in

caregivers’ quitting a job to provide care.4,5 Fre-

quently reported patient outcome measures include

the functional status of the patient and time-to-insti-

tutionalization.

Although the literature consistently reports a mod-erate relationship between level of patient disability

and caregiver psychological distress, there is consid-

erable variability in caregiver outcomes, which is

thought to be mediated and/or moderated by a va-

riety of factors, including caregivers’ economic status

and the availability of social-support resources, and

a host of individual-difference factors, such as gen-

der, personality attributes (optimism, self-esteem,

self-mastery), coping strategies used, and the quality

of the relationship between caregiver and care-recip-

ient.6–8 Researchers have further extended basic

stress/coping models to family caregiving and have

applied many additional theoretical perspectivesbor-

rowed from social and clinical psychology, sociology,

and the health and biological sciences to help under-

stand specific aspects of the caregiving situation. As

such, caregiving has provided a rich platform for con-

ducting basic and applied social- and behavioral-sci-

ence research across many disciplines. Consequently,

the scientific literature on caregiving now includes

nearly 2,000 published studies carried out by re-

searchers from all of the social-science and many of

the health-science disciplines. The research has pro-gressed from simple, often cross-sectional, descrip-

tive accounts of caregiving to complex hypothesis

testing longitudinal and experimental studies, and,

more recently, to intervention studies aimed at im-

proving caregiver and care-receiver health and well-

being outcomes.

Dementia Caregiving

Dementia caregiving is the most frequently studied

type of caregiving represented in the literature.5 Most

older adults with dementia receive assistance fromtheir spouse, but when the spouse is no longer alive

or is unavailable to provide assistance, adult children

usually step in to help. Adult daughters and daugh-

ters-in-law are more likely than sons and sons-in-law

to provide routine assistance with household chores

and personal care over long periods of time, and they

also spend more hours per week in providing assis-

tance.9 Although caregiving tasks are sometimes di-

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

3/10

Dementia and Family Caregiving

242 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004

vided among several family members or friends, the

more typical scenario is that most care is provided by

one individual.

Recent research has illuminated the differences be-

tween dementia caregiving and providing care to an

older relative or friend who has physical impairmentalone, confirming anecdotal reports that dementia

care is the more stressful type of family caregiving.

The national survey conducted by the National As-

sociation for Caregiving and the American Associa-

tion of Retired Persons (AARP) of over 1,500 caregiv-

ing households (with an oversampling of African

American, Hispanic, and Asian American caregivers)

found that, in comparison with caregivers of physi-

cally-impaired older adults, dementia caregivers pro-

vide more assistance and report that care provision is

more stressful; they give up their vacations or hobbies

more often, have less time for other family members,

and report more work-related difficulties.10

Further complicating the picture of providing on-

going care to an older relative with dementia is the

fact that 20%–24% of individuals with dementia also

suffer from a depressive syndrome, one of the com-

mon behavioral problems associated with demen-

tia.11,12 Not surprisingly, depressed dementia patients

have excess cognitive and physical disability, com-

pared with nondepressed dementia patients.13 Re-

gardless of which illness is the antecedent condition

in these cases of comorbidity (i.e., dementia or de-pression), caregivers are faced with an often over-

whelming number of challenges. Family members are

frequent initiators of depression treatment for the

older person and are often crucial in maintaining pa-

tient medication adherence through encouragement,

transportation to medical appointments, and other

logistical support.14,15

Relatively little is known about the experiences of

family members providing care to an older patient

with comorbid dementia and mood disorder. The

programmatic research of Teri and colleagues has

demonstrated that the care of an older relative with both dementia and depression is associated with high

levels of burden caused by to the relative’s emotional,

cognitive, and behavioral problems, as well as the

need for supervision and physical assistance with

daily activities.16 In one study, 10% of these caregivers

met criteria for major depressive disorder, and 62%

met criteria for minor depression.17 Burden in this

population of caregivers may result from attempts to

manage patient antidepressant medication along

with other prescribed medications, difficulty in dis-

tinguishing between dementia and depressive symp-

toms, and negative attitudes toward depressive dis-

order. Clearly, assessment and intervention with this

population are sorely needed.

Health Effects of Caregiving

Although family caregivers perform an important

service for society and their relatives, they do so at

considerable cost to their own well-being. There is

strong consensus that caring for an elderly individual

with disability is burdensome and stressful to many

family members and contributes to psychiatric mor-

bidity in the form of higher prevalence and incidence

of depressive and anxiety disorders.8,17–19 Most stud-

ies indicate that female caregivers report higher levelsof depressive and anxiety symptoms and lower levels

of life satisfaction than male caregivers.20,21 Research-

ers have also suggested that the combination of loss,

prolonged distress, physical demands of caregiving,

and biological vulnerabilities of older caregivers may

compromise their physiological functioning and in-

crease their risk for physical health problems. Sup-

port for this hypothesis is found in studies showing

that caregivers are less likely to engage in preventive

health behaviors,19 that they show evidence of dec-

rements in immunity measures when compared with

control subjects18,22,23 and exhibit greater cardiovas-cular reactivity24 and slowing of wound healing.25

The evidence also suggests that some caregivers are

at increased risk for serious illness,22,26 and one recent

study shows them to be at increased risk of mortal-

ity.27 Overall, the convergence of evidence from these

studies indicates that a meaningful risk for adverse

psychiatric and physical health outcomes exists for a

subgroup of caregivers who sustain high levels of

caregiving demands, experience chronic stress asso-

ciated with caregiving, are physiologically compro-

mised, and have a history of psychiatric illness.8,28

Intervention Research

The accumulating evidence on the personal, social,

and health impacts of caregiving has generated inter-

vention studies aimed at decreasing the burden and

stress of caregiving. The dominant theoretical model

guiding the design of caregiver interventions is the

stress/health model illustrated in the left column of

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

4/10

Schultz and Martire

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004 243

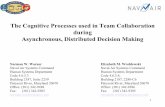

FIGURE 1. The Stress/Health Model applied to caregiving and associated interventions

Primary Stressors

Care-Recipient:Disability, Problem

Behaviors, Loss

Perceived Stress

Morbidity/Mortality

Stress/Health Process Interventions

Pharmacologic Treatment,Family Counseling

Social Support

Self Care,Preventive Health Practices

Communication

Skills Training

Education

Secondary Stressors

Family Conflict,Work Difficulties

Appraisal of demands and adaptive capacities

Emotional/ Behavioral Response

Figure 1. According to this model, the primary stress-

ors being placed on the caregiver include the level of

patient cognitive impairment, the frequency of pa-

tient problem behaviors (e.g., agitation, restlessness,

wandering, aggression), number of hours per week

spent providing physical assistance with instrumen-tal or personal activities of daily living (e.g., bathing,

dressing, shopping, housework), and helping the pa-

tient to negotiate the healthcare system (e.g., getting

to physician appointments, taking prescribed medi-

cations). Problem behaviors of the older adult are of-

ten the most frequently endorsed stressor of dementia

caregiving, even compared with provision of assis-

tance with daily tasks.8

A second set of stressors, thought to be a conse-

quence of the primary aspects of caregiving, may be

less obvious to healthcare professionals because of their relatively limited contact with patients and fam-

ily caregivers.29 For example, as a result of the pa-

tient’s physical and emotional dependency on the

caregiver and fundamental changes in the nature of

their relationship, the quality of the relationship be-

tween caregiver and care-recipient often decreases

over time. Decreased relationship quality and even

outright conflict between the primary family care-

giver and other family members is another secondary

stressor of caregiving, in that family members often

disagree about the division of responsibility for care-

giving tasks and the best way to carry out these tasks.

Job-related difficulties, such as missing work, beingoverly tired at work, and missing new job opportu-

nities or chances for promotion, are also a common

consequence of the primary stressors of caregiving.30

Caregivers evaluate whether demands pose a po-

tential threat and whether they have sufficient coping

strategies or capacities. If they perceive the demands

as threatening and their coping resources as inade-

quate, they will experience stress. The experience of

stress is assumed to contribute to negative emotional,

physiological, and behavioral responses that put the

individual at risk for physical and psychiatric dis-ease. Not illustrated in the model are numerous feed-

back loops showing how responses at one stage of

the model subsequently feed back to earlier stages.

For example, a negative emotional response to a stres-

sor might subsequently increase the stressor itself or

have a negative effect on the appraisal of the stressor.

This could occur when a caregiver becomes dis-

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

5/10

Dementia and Family Caregiving

244 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004

tressed in response to the disruptive or self-neglect-

ing behaviors of the care-recipient, who then becomes

more disruptive because of the caregiver’s anger to-

ward him or her, and so on.

The right column of Figure 1 illustrates how vari-

ous interventions might affect the stress/health pro-cess. For example, interventions targeting the care-

recipient (e.g., reducing care-recipient dependency or

disruptive behaviors) are designed to alter the pri-

mary stressors impinging on the caregiver. Interven-

tions targeting caregiver knowledge about caregiving

and the availability of social support and other re-

sources should have their primary impact on caregiv-

ers’ appraisal of demands and adaptive capacities. In-

terventions targeting caregiver affect, such as feelings

of depression and anxiety, are aimed at altering the

emotional response of the caregiver. Finally, interven-

tions targeting caregiver behavior should have direct

effects on the behavioral responses of the caregiver.

Early intervention studies were primarily psycho-

social and targeted caregiver appraisals of their re-

sources and situation. These interventions involved

mostly support groups, individual counseling, and

educational approaches. Evidence from this first

wave of research was inconsistent and showed mod-

est therapeutic benefits, as measured by global rat-

ings of well-being, mood, stress, psychological

status, and burden.31 Recent research focusing on

more rigorous randomized controlled-trial designsevaluated a broader range of intervention programs

involving individual or family counseling, case

management, skills training, environmental modi-

fication, behavior-management strategies, and com-

binations thereof.5,32–34 Evidence from these studies

suggests that combined interventions targeting mul-

tiple levels of the stress/health model and multiple

individuals simultaneously (i.e., caregiver and pa-

tient) produce a significant improvement in caregiver

burden, depression, subjective well-being, perceived

caregiver satisfaction, ability/knowledge, and, some-

times, care-recipient symptoms.33,34

That is, interven-tions combining different strategies and providing

caregivers with diverse services and supports tend to

generate larger effects than narrowly focused inter-

ventions. Similarly, single-component interventions,

with higher intensity (frequency and duration), have

a greater positive impact on the caregiver than com-

parable interventions with lower intensity.35 Inter-

vention effects tend to be larger for increasing care-

giver knowledge and skill than for decreasing burden

and depression. Also, intervention effects for caregiv-

ers of persons with dementia tend to be smaller than

those for caregivers of other types of care-recipients.32

Although many caregiving intervention studies

demonstrate statistically significant effects, it is per-haps more important to ask whether these effects

have practical value to either the individual or soci-

ety. Defining what is practically important in the con-

text of caregiving depends to some extent on whose

perspective we take. However, most clinicians would

agree that successfully treating a case of major or mi-

nor depression in the caregiver is clinically meaning-

ful, and most government agencies would argue that

delaying institutionalization of the patient is an im-

portant and desirable outcome from a societal per-

spective because of the high costs of long-term care.

Examples of clinically-meaningful depression treat-

ment include the work of Gallagher-Thompson et

al.,36 Mittelman et al.,37 and Teri et al.17 Teri et al. re-

port clinically significant improvement in caregiver

depression in two active treatment conditions (i.e.,

pleasant-events or problem-solving, lasting 9 weeks.)

Similarly, Gallagher-Thompson et al.36 reported im-

proved or stable depression diagnosis among 80% of

caregivers who participated in a 10-week life-satis-

faction psychoeducational group. Several studies

have reported results showing delays in institution-

alization or reductions in the rate of institutionaliza-tions among care-recipients with dementia.37–41 In the

Mittelman et al. study,37 for example, care-recipients

in the intervention group were placed in nursing

homes significantly later (median: 329 days) than in

the control group. However, achieving this outcome

required a relatively intensive 1-year intervention

that included six counseling sessions, 4 months of

support-group attendance, and clinician telephone

support, as needed.

A persistent limitation of caregiver-intervention re-

search is that individual studies offer relatively small

sample sizes, test a limited range of interventionstrategies, and are geographically-bound. Also, it has

been difficult to identify the optimal mix of program

elements for a given caregiver/care-recipient dyad,

and the clinical significance of treatment effects has

not been systematically evaluated.33 Some of these

limitations are currently being addressed in the most

ambitious caregiver-intervention trial to date, re-

ferred to as REACH (Resources for Enhancing Alz-

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

6/10

Schultz and Martire

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004 245

heimer’s Caregiver Health). REACH is a unique,

multi-site research program sponsored by the Na-

tional Institute on Aging (NIA) and the National In-

stitute on Nursing Research (NINR). Phase 1 of

REACH was recently completed; it tested several dif-

ferent social and behavioral interventions designed toenhance family caregiving for AD and related disor-

ders. The approach was through randomized clinical-

trial methods.42–46 A total of 1,222 caregivers and

care-recipients participated in this trial. Although dif-

ferent interventions were carried out at different sites,

all sites used the same measurement protocol, en-

abling the researchers to carry out pre-planned meta-

analysis to assess the effects of active treatments ver-

sus control conditions,44 as well as to conduct

hierarchical linear modeling to identify key elements

of interventions that contributed most to positive

caregiver outcomes.45,46 The results showed that,

among all caregivers combined, active treatments

were superior to control conditions in reducing care-

giver burden. In particular, women and those with

less education (high school or lower) who were in

active treatment reported significantly lower burden

than similar individuals in control conditions. Care-

givers in active interventions who were Hispanic,

those who were non-spouses, and those who had less

than high school education reported lower depres-

sion scores than those with the same characteristics

who were in control conditions. Interventions thatemphasized behavioral-skills training had the great-

est impact in reducing caregiver depression.

Based on findings of Phase 1, a new intervention

that combines the most promising elements of the

Phase 1 trial was developed and is currently being

tested. Informed by lessons learned from the Phase 1

trial, the strategy being pursued in Phase 2 involves

the assessment of caregiver risk in five domains:

safety, social support, health and self-care, emotional

well-being, and care-recipient problem behaviors.

The intervention addresses all five domains, but at

varying doses, depending on the risk profile of thecaregiver. Results from this study will be available in

2005.

Modeled after the ongoing REACH study, Table 1

identifies five domains of risk for caregivers, inter-

vention options derived from the stress/health

model, and suggested outcomes for monitoring im-

pact. The key risk areas include safety, self-care and

preventive health behaviors, caregiver support, de-

pression and distress, and problem behaviors of the

care-recipient. As shown in the table, for each area of

risk, there are multiple intervention options, as well

as outcomes assessment strategies. A comprehensive

approach to caregiver management would require as-

sessment of all five areas of risk, tailoring of inter-ventions to match the risk profile of the individual,

and assessment of multiple outcomes. Although this

may be the ideal, implementing this approach will be

challenging. First, we must develop ways of quickly

and accurately assessing caregiver risk. The initial

step in this process requires identifying and address-

ing issues of patient and caregiver safety (e.g., does

the patient drive, have access to weapons?). This pro-

cess should be followed by assessment of the clinical

status of the caregiver, to identify problems such as

major depression and other medical conditions thatrequire intervention. Second, we need to develop

guidelines on which intervention options are most

appropriate for a given individual on the basis of

caregiver vulnerabilities and coping resources. For

example, caregivers who are not knowledgeable

about local referral resources (e.g., local chapters of

the Alzheimer’s Association, Area Agency on Aging

services) may benefit from case management, respite,

support, or homemaker services available from these

organizations. Clinicians interested in directly pro-

viding these types of services can consult “how-to”

books, designed to educate healthcare professionalson how to provide a wide array of caregiver services,

including case management, counseling, and sup-

port.47 The third challenge for the clinician is assess-

ing the effects of clinical interventions. This will re-

quire that we develop cost-effective methods for

monitoring caregiver status over time. Finally, we

must identify how best to practically implement this

approach and ways in which it might be paid for.

An individual clinician is unlikely to have the re-

sources to address all of the caregiver’s needs, al-

though the more problems addressed, the better thelikely outcome for the caregiver. Addressing multiple

problems with relatively intense interventions will

generate the best possible outcomes, and involving

both patient and caregiver is likely to be more effec-

tive than focusing on the caregiver or patient alone.34

Clinicians also can be instrumental in recruiting other

family members to share the burden of care. Involv-

ing other family members is particularly important

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

7/10

Dementia and Family Caregiving

246 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004

TABLE 1. Risk appraisal, intervention options, and suggestions for outcome assessment strategies for caregivers of patients with

dementia

Risk Area Intervention Options Outcome Assessment

Safety of caregiver and care-recipient(e.g., driving, access to weapons,chemicals, medications, householdobstacles)

Home assessment and alterations; patientmonitoring devices; removing access

Reduction or elimination of targeted risk area

Self-care and preventive health behaviorsof caregiver (e.g., sleep quality, diet,exercise, vaccinations, screening)

Respite; education; monitoring;facilitating access

Improved self-care, health behaviors,better health

Support of caregiver (e.g., informational,instrumental, and emotional support)

Information and referral sources; supportgroups; family therapy, counseling

Enhanced knowledge on caregiving,disease, and aging; increased respiteand satisfaction with support; fewer negative interactions

Depression, distress of caregiver Medication; counseling; psychotherapy Depressive Symptoms (CES-D); ClinicalDepression (Ham-D)

Disruptive and problem behaviors of care-recipient

Behavioral skills training; medications Reduced burden

for spousal caregivers, who may jeopardize their own

health to care for their loved one.

Existing Guidelines for Practitioners

Caregivers play a critical role in the diagnosis and

treatment of patients with dementia. Because caregiv-

ers have around-the-clock access to patient behavior

and the knowledgebase to identify significant

changes in patient functioning, they serve as a critical

source of information for the clinical assessment of

the patient.48 Also, treatments and behavioral inter-

ventions for the patient are typically implemented by

the caregiver, who has day-to-day contact with the

patient. The centrality of the caregiving role in patient

diagnosis and management has resulted in guidelines

and recommendations on working with caregivers of patients with dementia published by the major medi-

cal societies, including the American Medical Asso-

ciation (AMA), the American Psychiatric Association

(APA), and the American Association for Geriatric

Psychiatry (AAGP). For example, the APA, in their

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Alz-

heimer’s Disease and other Dementias of Late Life,49 em-

phasizes that the psychiatric management of the pa-

tient must be based on a solid alliance with the

patient and family.

The AMA takes a similar view when it recommends

that understanding family caregiver needs and chal-lenges are essential aspects of caring for persons with

dementia.50 The AMA advocates a physician/care-

giver/patient partnership approach, in which physi-

cians provide information and referral to caregivers

as well as monitor caregiver functioning to ensure

their health and well-being. To help implement the

latter goal, the AMA has developed a brief assess-

ment instrument, called the Caregiver Self-Assess-

ment Tool, to be used by physicians to identify care-

givers at risk for adverse health outcomes.51

Caregivers are asked to answer 18 questions, assess-

ing their level of distress and health and whether or

not they feel overwhelmed, lonely, irritable, have

poor sleep because of caregiving, are satisfied with

the support they receive from family members, and

so forth. Persons who report high levels of distress

are encouraged to consider 1) getting a check-up from

a doctor; 2) obtaining respite from caregiving; and 3)

joining a support group. Although this tool has not

been empirically evaluated, it provides valuable

guidance on the signs and symptoms of excessive

burden among caregivers.

AAGP also acknowledges the essential role of care-

givers in providing reasonable and appropriate care

for dementia patients and has issued a formal posi-

tion statement on family caregivers and healthcare

professionals.52 AAGP takes the position that family

and caregiver counseling are medically necessary for

the appropriate treatment of dementia, that counsel-

ing often requires family or caregiver visits without

the patient present, and that caregiver counseling

should be considered a reimbursable, covered ser-

vice. The rationale for this position is based on theobservation that caregivers must receive guidance

from physicians to observe, monitor, and manage the

patient with dementia, and that providing this guid-

ance is time-consuming and costly.

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

8/10

Schultz and Martire

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004 247

Of course, it is likely that there is much variability

in the extent to which clinicians follow practice

guidelines for involving family caregivers in the man-

agement of dementia. One recent survey examined

how closely such guidelines are followed by regis-

tered nurses, primary-care physicians, social work-ers, psychologists, nurse-practitioners, neurologists,

and psychiatrists. This study concluded that clini-

cians were most divergent from practice guidelines

in the areas of promoting referral of caregivers to sup-

port services and community organizations and in-

creasing caregivers’ knowledge of behavior-manage-

ment techniques.53

On the whole, these guidelines are consistent with

and are supported by empirical literature and clinical

experience, but, at this point, they are not very com-

prehensive. They need to be expanded and elabo-

rated with greater emphasis on ways in which they

can be operationalized. Specifically, guidelines

should address four issues: 1) identifying caregivers/

patients at risk for adverse outcomes; 2) methods for

addressing identified risk areas; and 3) methods for

assessing clinically meaningful outcomes. A fourth

and final issue concerns how and by whom these

guidelines should be implemented and paid for.

Future Directions

Caregiving presents difficult, sometimes intracta- ble problems, and although we have learned a great

deal about how to describe and characterize the chal-

lenges of caregiving, assess its impact on family

members, and identify promising intervention ap-

proaches, much more needs to be done. For example,

with the exception of a few recent studies, we know

relatively little about transitions into and out of the

caregiving role. Understanding pre- or early caregiv-

ing stages may enable us to develop preventive in-

tervention strategies that protect the caregiver from

adverse outcome later in the caregiving experience.

Recent work on the transitions out of the caregivingrole, through the death of the care-recipient, has shed

new light on our understanding of bereavement by

showing that the response to death is strongly influ-

enced by the caregiving experience.54,55 Highly

stressed caregivers show remarkable signs of recov-

ery after the death of their loved one, suggesting that

much of the work of dealing with loss occurs before

the death. Clinicians can play an important role in

helping the caregiver deal with loss while they are

caregivers.

Caregiving, by definition, occurs in a social rela-

tional context. Yet, we have paid little attention to the

reciprocal impact that patients and caregiver have on

each other. Some recent studies56,57 have shown thatthere is a high degree of similarity in affect among

marital pairs, controlling for known predictors of

well-being. This suggests that the affect of the care-

recipient may spill over to the caregiver, and vice

versa, initiating a downward spiral that undermines

the quality of life of both individuals. An important

implication of this finding is that clinical interven-

tions that simultaneously treat the patient and the

caregiver are likely to achieve the largest effects.

The existing caregiving literature tells us a great

deal about who is at risk for negative health out-

comes, yet these findings have not been systemati-

cally applied in intervention studies. Studies have

been either narrowly focused on a specific problem,

such as providing respite for the caregiver, or of the

“kitchen-sink” variety, where interventionists pro-

vide a little bit of everything. Neither approach has

paid much attention to the articulation or measure-

ment of mechanisms through which interventions

might achieve their desired effects. This should re-

ceive high priority in future studies. Other new di-

rections for intervention research include testing in-

novative approaches to supporting informalcaregivers through monitoring technology and so-

phisticated communication systems.58,59 For example,

telemetry and other monitoring devices have been

used with dementia patients to observe their move-

ments and location. Telephones and, more recently,

personal computers have been used to provide social

support, deliver technical assistance, and enhance

caregivers’ understanding of aging and disability and

their role as caregivers. Computers, videotapes, and

telephones have also been used as a means for enter-

taining or distracting the care-recipient and provid-

ing respite to caregivers. It is conceivable that in thenot-too-distant future, healthcare providers, family

members, and patients will be linked through ubiq-

uitous computing environments, giving clinicians

and family members on-line access to patient status

and functioning whenever they wish.59

As the complexity of caregiving tasks increases, it

will be all the more important to develop methods

for assessing the quality of care provided and deter-

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

9/10

Dementia and Family Caregiving

248 Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004

mining who can and cannot provide the necessary

care, what types of assistance (training and supervi-

sion) the caregiver needs in order to ensure high-

quality care, as well as methods for monitoring care-

giving performance. These issues will become all the

more important as the demands for post-acute care

increase, and caregivers are required to care for older

individuals with underlying chronic disability along

with special needs generated by an acute illness epi-

sode. Clinicians will play a critical role in defining

and assessing adequate care.

Addressing the challenges of caregiving in Amer-

ican society now and in the future will require not

only innovative research and clinical applications but

also macro-level social experiments to support and

motivate caregivers, as well as changes in healthcare

policy that fully recognize the role of the caregiver as

a healthcare resource. Developing and evaluating the

impact of healthcare, financial, and workplace poli-

cies (e.g., reimbursement, tax credits, pension

schemes, caregiving leaves, and payment to caregiv-

ers) will become a critical task for future researchersand policymakers. Healthcare providers of all types

will undoubtedly play a major role in shaping future

caregiver policy.

This work was supported by grants from the National

Institute on Aging (K01 MH065547, R01 AG15321, U01-

AG13313), National Institute of Mental Health (R01

MH46015, P30 MH52247), and National Institute for

Nursing Research (R01 NR08272), and grant P50

HL65111-65112 (Pittsburgh Mind-Body Center) from the

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

1. Health and Human Services: Informal Caregiving: Compassion in

Action. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Ser-

vices, 1998

2. Alecxih LMB, Zeruld S, Olearczyl B: Characteristics of caregivers

based on the survey of income and program participation. Na-

tional Family Caregiver Support Program: Selected Issue Briefs.

Falls Church, VA, The Lewin Group, 2001

3. Spector WD, Fleishman JA, Pezzin LE, et al: The Characteristics

of Long-Term Care Users. AHRQ Research Report. AHRQ Publi-

cation No. 00-0049. Rockville, MD, Agency for Health CarePolicy

and Research, Department of Medicine, JohnHopkins University,

Urban Institute, 2001

4. Biegel D, Sales E, Schulz R: Family Caregiving in Chronic Illness:

Heart Disease, Cancer, Stroke, Alzheimer’s Disease, and ChronicMental Illness. Newbury Park, CA, Sage Publications, 1991

5. Schulz R (ed): Handbook on Dementia Caregiving: Evidence-

Based Interventions for Family Caregivers. New York, Springer,

2000

6. Haley WE, Roth DL, Coleton MI, et al: Appraisal, coping, and

social support as mediators of well-being in black and white fam-

ily caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Consult Clin

Psychol 1996; 64:121–129

7. Yee J, Schulz R: Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity

among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist

2000; 40:147–164

8. Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, et al: Psychiatric and physical

morbidity effects of Alzheimer’s disease caregiving: prevalence,

correlates, and causes. Gerontologist 1995; 35:771–791

9. Montgomery RJ: Gender differences in patterns of child–parentcaregiving relationships, in Gender, Families, and Elder Care. Ed-

ited by Dwyer JW, Coward RT. Newbury Park, CA, Sage Publi-

cations, 1992, pp 65–83

10. Ory MG, Hoffman RR, Yee JL, et al: Prevalence and impact of

caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and non-

dementia caregivers. Gerontologist 1999; 39:177–185

11. Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz TT, et al: Mental and behav-

ioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County

Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:708–714

12. Meyers BS: Depression and dementia: comorbidities, identifica-

tion and treatment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1998; 11:201–

205

13. Rovner BW, Broadhead J, Spencer M, et al: Depression and Alz-

heimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:350–353

14. Hinrichsen GA: Adjustment of caregivers to depressed older

adults. Psychol Aging 1991; 6:631–639

15. Hinrichsen GA, Zweig R: Family issues in late-life depression.

Journal of Long-Term Home Health Care 1994; 13:4–15

16. Teri L: Behavioral treatment of depression in patients with de-

mentia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1994; 8:66–74

17. Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, et al: Behavioral treatment of de-

pression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Ger-

ontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997; 52B:P159–P16618. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Dura JR, Speicher CE, et al: Spousal caregivers

of dementia victims: longitudinal changes in immunity and

health. Psychosom Med 1991; 53:345–362

19. Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, et al: Health effects of care-

giving: The Caregiver Health Effects Study: an ancillary study of

The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med 1997; 19:110–

116

20. Miller B, Cafasso L: Gender differences in caregiving: fact or ar-

tifact? Gerontologist 1992; 32:498–507

21. Yee JL, Schulz R: Genders differences in psychiatric morbidity

among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist

2000; 40:147–164

22. Kiecolt-Glaser J, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al: Chronic stress

alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older

adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93:3043–304723. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK: Chronic stress modulates the virus-

specific immune response to latent herpes simplex virus Type 1.

Ann Behav Med 1997; 19:78–82

24. King AC, Oka RK, Young DR: Ambulatory blood pressure and

heart rate responses to the stress of work and caregiving in older

women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1994; 49:239–245

25. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarkey WB, et al: Slowing of

wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet 1995; 346:194–

196

26. Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Semple SJ, et al: Longitudinal analysis of

-

8/13/2019 Aj Gp Family Care Giving

10/10

Schultz and Martire

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:3, May-June 2004 249

multiple indicators of health decline among spousal caregivers.

Ann Behav Med 1997; 19:101–109

27. Schulz R, Beach S: Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The

Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA 1999; 282:2215–2219

28. Burton LC, Zdaniuk B, Schulz R, et al: Transitions in spousal care-

giving. Gerontologist 2003; 43:230–241

29. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al: Caregiving and the stress

process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontol-

ogist 1990; 30:583–594

30. Neal MB, Chapman NJ, Ingersoll-Dayton B, et al: Balancing Work

and Caregiving for Children, Adults, and Elders. Newbury Park,

CA, Sage, 1993

31. Knight BG, Lutzky SM, Macofsky-Urban F: A meta-analytic review

of interventions for caregiver distress: recommendations for fu-

ture research. Gerontologist 1993; 33:240–248

32. Sorensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P: How effective are inter-

ventions with caregivers? an updated meta-analysis. Gerontolo-

gist 2002; 42:356–372

33. Schulz R, O’Brien A, Czaja S, et al: Dementia caregiver interven-

tion research: in search of clinical significance. Gerontologist

2002; 42:589–602

34. Brodaty H, Green A, Koschera A: Meta-analysis of psychosocial

interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. J Am Ger-iatr Soc 2003; 51:657–664

35. Kennet J, Burgio L, Schulz R: Interventions for in-home caregiv-

ers: a review of research 1990 to present, in Handbook on De-

mentia Caregiving: Evidence-Based Interventions for FamilyCare-

givers. Edited by Schulz R. New York, Springer, 2000, pp 61–126

36. Gallagher-Thompson D, Lovett S, Rose J, et al: Impact of psycho-

educational interventions on distressed family caregivers. J Clin

Geropsychol 2000; 6:91–110

37. Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E et al: A family intervention

to delay nursing home placements of patients with Alzheimer’s

disease: a randomized, controlled trial. JAMA 1996; 276:1725–

1731

38. Chu P, Edwards J, Levin R, et al: The use of clinical case manage-

ment for early-stage Alzheimer’s patients and their families. Am J

Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2000; 15:284–29039. Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Sivenius J, Sulkava R: Support program for

dementia patients and their carers: the role of the dementia fam-

ily care coordinator is crucial, in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related

Disorders. Edited by Iqbal K, Swaab DF, Winblad B et al. West

Sussex, UK, Wiley, 1999, pp 795–802

40. Hébert R, Leclerc G, Bravo G, et al: Efficacy of a support pro-

gramme for caregivers of demented patients in the community:

a randomized, controlled trial. ArchGerontol Geriatr 1994;18:1–

14

41. Mohide EA, Pringle DM, Streiner DL, et al: A randomized trial of

family caregiver support in the home management of dementia.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38:446–454

42. Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, et al: Introduction to the special

section on Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’sCaregiverHealth

(REACH). Psychol Aging 2003; 18:357–360

43. Wisniewski S, Belle SH, Coon DW, et al: The Resources for En-

hancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): Project design

and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging 2003; 18:375–384

44. Gitlin L, Belle SH, Burgio L, et al: Effects of multicomponent in-

terventions on caregiver burden and depression: The REACH

multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up. Psychol Aging 2003;

18:361–374

45. Czaja SJ, Schulz R, Lee CC, et al: A methodology for describing

and decomposing complex psychosocial and behavioral inter-

ventions. Psychol Aging 2003; 18:385–395

46. Belle SH, Czaja SJ, Schulz R, et al: Using a new taxonomy to

combine the uncombinable: integrating results across diverse

caregiving interventions. Psychol Aging 2003; 18:396–405

47. Mittelman MS, Epstein C, Pierzchala A: Counseling the Alzhei-

mer’s caregiver: a resource for health careprofessionals.Chicago,

IL, American Medical Association Press, 2002

48. Tierney MC, Herrmann, N, Geslani DM, et al: Contribution of

informant and patient ratings to the accuracy of the Mini-Mental

State Exam in predicting probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Ger-

iatr Soc 2003; 51:813–818

49. American Psychiatric Association: Clinical Resources: Practice

Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease

and Other Dementias of Late Life. Washington, DC, American

Psychiatric Association, 1997; http://www.psych.org/clin_res/

pg_dementia.cfm

50. American Medical Association: Medicine and Public Health: Is-sues in Family Caregiving. Washington, DC, American Medical

Association, 2002; http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/cate-

gory/5032.html

51. American Medical Association: Medicine and Public Health:

Health Risks of Caregiving. Washington, DC, American Medical

Association, 2002; http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/cate-

gory/8802.html

52. American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry: Family and Care-

giver Counseling in Dementia: Medical Necessity. Bethesda, MD,

American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 2001; http://

www.aagponline.org/prof/position_dementia.asp

53. Rosen CS, Chow HC, Greenbaum MA, et al: How well are clini-

cians following dementia practice guidelines? Alzheimer Dis As-

soc Disord 2002; 16:15–23

54. Schulz R, Beach SR, Lind B, et al: Involvement in caregiving andadjustment to death of a spouse: findings from the Caregiver

Health Effects Study. JAMA 2001; 285:3123–3129

55. Schulz R, Mendelsohn A, Haley WE, et al: End-of-life care and the

effects of bereavement among family caregivers of persons with

dementia. New Engl J Med 2003; 349:1936–1942

56. Bookwala J, Schulz R: Spousal similarity in subjective well-being:

The Cardiovascular Health Study. Psychol Aging 1996; 11:582–

591

57. Tower RB, Kasl SV: Gender, marital closeness, and depressive

symptoms in elderly couples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci

1996; 51B:115–129

58. Schulz R, Lustig A, Handler S, et al: Technology-based caregiver

intervention research: current status and future directions. Ger-

ontology 2002; 2:15–247

59 . Dishman E, Matthews JT, Dunbar-Jacob J: Everyday health, tech-

nology for adaptive aging, in Steering Committee for the Work-

shop on Technology for Adaptive Aging. Edited by Van Hemel S.

Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2004, pp 173–200