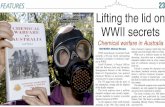

The Mustard Gas War

-

Upload

alan-challoner -

Category

Documents

-

view

255 -

download

5

Transcript of The Mustard Gas War

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

1/31

Italy v Abyssinia

The Mustard Gas War

1935-1936

Alan Challoner MA

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

2/31

Page 2 of 31

US Newspapers October 1935

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

3/31

Italy v Abyssinia

The Mustard Gas War

1935-1936

From Wal Wal to Warsaw

The Italian-Abyssinian War of 1935-36 was a key turning point both in the fortunes of the League of Nations

and in Mussolinis foreign policy; as a result of the invasion, his relations with Britain and France deterioratedand he drew closer to Hitlers Germany.

Since WW2 Britain and America have become great powers in terms of monitoring theworld for aggression which could affect them and other countries. However, in 1935 it wasa different story.

In 1935 the Italy-Abyssinia war was an escapade that should not have been possible.However, the League of Nations was weak; it was headed by Britain and France and theyhad other agendas as did the isolationist USA and they collectively also failed to stop thiswicked and preposterous act of pure aggression by Italy on what could be described as aprimitive country in Abyssinia.

The BattleThe BattleThe BattleThe Battle of Adowaof Adowaof Adowaof Adowa 1896189618961896

As the 20th century approached, most of 19th century Africa had been carved upbetween the various European powers and Abyssinia was the only African country that wasstill completely free from European domination. It had stoutly resisted an attack by Italy in1896 following some political trickery that involved Italy putting a treaty with Abyssinia intotwo languages (Amharic and Italian), each with a different wording. Fortunately Abyssiniarealised what was being attempted and refused to sign. This was the First Italian-Abyssinian

War.

The Italian officer in charge of that battle was General Oreste Baratieri who at the time wasthe Governor of Eritrea (which was to the north of Abyssinia). The Italians had created thecolony of Eritrea around Asmara, in the 19th century. The Abyssinian forces werecommanded by Emperor Menelik.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

4/31

Page 4 of 31

Menelik outmanoeuvred the Italians. On the evening of 29 February 1896, Baratieri metwith his brigadiers but they could not agree amongst themselves about tactics and soBaratieri delayed making a decision for a few more hours, claiming that he needed to waitfor some last-minute intelligence, but in the end announced that the attack would start thenext morning.

Instead of attacking, as Baratieri hoped he would, Menelik concentrated his forces atAdowa and waited. Baratieri planned to send his troops along different routes to meet on

the high ground overlooking Adowa. However the country was so difficult to traverse thatsoon the Italian forces became lost and confused. As the confusion grew great holesopened in the Italian lines and just at this time Ras Makonnen of Harar (Father of EmperorHaile Selassie) arrived with 30 thousand warriors to join the battle. He was joined by hordesof Menelik's warriors.

In the battle that began on 1 March 1896, wave upon wave of Abyssinian soldiers attackedthe Italians, causing them to flee in total confusion. At the end of the battle 289 Italianofficers, 2, 918 European soldiers and about 2, 000 askari (Eritreans fighting for the Italians)were dead. More were wounded, missing or captured. Menelik forced the rest of thecaptured troops to march to Addis Ababa where they were held until the Italiangovernment paid 10 million lire in reparation money. The Italians never forgot that insult totheir national pride.

In 1906, Italy, England, and France, without consulting Emperor Menelik, discreetly gottogether and signed an agreement in which England and France acknowledged Italy'spriority in Abyssinia. The British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, and the French andItalian ambassadors in London accordingly signed a Tripartite Convention, on 13thDecember 1906. It declared, in Article 1, that it was in the common interest of the threepowers to maintain the integrity of Abyssinia, while arriving at an understanding as totheir conduct in case of a change in the situation, by which they meant Menilek's demise.The three signatories jointly agreed, in Article 3, that in such an eventuality they wouldmaintain a policy of neutrality, and refrain from military intervention, except to protect theirlegations and foreign nationals, and that not one of the three powers would take anymilitary action in the country except in agreement with the other two. 1

Part of this agreement stipulated that Italy would never hinder the operation of the French -owned railway from Addis Ababa to Djibuti, or the flow of Blue Nile water from AbyssiniasLake Tana into the White Nile, which fed England's dependencies, Egypt and the Sudan.

However, by the early 1930s, Benito Mussolini had become the Fascist dictator of Italy andhe was aggrieved that his country still did not have the colonies that some other Europeancountries had and he then commenced his attempt to enlarge the Italian Empire byacquiring Abyssinia by fair means or foul.

Italy having tried and failed to conquer Abyssinia in 1896, felt that they didnt get their fairshare of territory after World War I when the Treaty of Versailles (1919) made peace anddecided who would rule Germanys former colonies. The invasion of Abyssinia would makeup for these disappointments. Abyssinia and the territories Italy already held in East Africa

would join together to make a new Italian empire in the region.

Abyssinia had the support of the League of Nations, but did not have an army to match theItalians. Abyssinia was still a backward country in many ways and although the countryhad a large fighting force it was largely one that fought barefoot and used spears andswords rather than the guns, artillery, tanks and planes that Italy could command.

1 Pankhurst, R. A History of Early Twentieth Century Ethiopia. 3: Menilek's Failing Health,European Attempts to Partition Ethiopia, and the Rise of Lej Iyasu.http://www.linkethiopia.org/guide/pankhurst/twentieth_century/twentieth_century_3.html

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

5/31

Page 5 of 31

The League of NationsThe League of NationsThe League of NationsThe League of Nations

Following the First World War several world leaders such as Woodrow Wilson of America 2and Jan Smuts of South Africa3, began advocating the need for an internationalorganization to preserve peace and settle disputes by arbitration. In September 1916,Robert Cecil, a member of the British government, wrote a memorandum in which heargued that civilisation could survive only if it could develop an international system that

would ensure peace. Italy was a founder member, joining at its inception on January 10,1920. Abyssinia was admitted in 1923.

The aims of the League of Nations was to maintain peace through collective security; so, ifone country attacked the other, the member states of the League would act together,collectively, to restrain the aggressor, either by economic or by mil itary means.

The decision making processes of the League were organised around a voting system.Each member of the General Assembly (this included representatives of all member states)had one vote and decisions had to be unanimous. Each member of the Council (initiallycomposed of four permanent members) had one vote and decisions had to be unanimousbut the permanent members had the right of veto.

The procedure for solving disputes was that all disputes were taken to the League and itwould first make suggestions; then apply economic sanctions and, if necessary, send anarmy. Any member breaking the covenant would face action by the rest with the councilrecommending how much army each member should send.

Lasting from 1920 to 1946, the League of Nations was by general consensus a disaster; itwas the much vaunted international instrument of peace that wholly failed to prevent asecond world war. What is more its failure to implement actions that could have stoppedthe Italian Abyssinian War in 1935 eventually led, by that failure, to the greatly increasedconfidence of Adolf Hitler that allowed him to act with disdain for the League as heattempted to conquer Europe.

In the first Macdonald Labour Government of 1924, Arthur Henderson served as HomeSecretary, and five years later when Labour returned to power, he became Foreign

Secretary. At the Foreign Office, Hendersons policy was to try and establish Britainsleadership in seeking to secure foundations for a lasting peace through the League ofNations.

In 1932 Lord Cecil said of the League of Nations: The whole International atmosphere willchange as if by magic. Little did those present to hear him know just how different thismagic would be from what Cecil anticipated. It is significant that the secondItalian/Abyssinian War was the touch-paper for the later event of WW2 and that was tochange not only Europe but many other parts of the world.

See video at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwbrg0R5o8w

2 ThomasWoodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 February 3, 1924) was the 28th President ofthe United States (1913-1921).

3 Jan Christiaan Smuts (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a prominent South African andBritish Commonwealth statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holdingvarious cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 until1924 and from 1939 until 1948.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

6/31

Page 6 of 31

Mussolini believed that Britain and France would permit his invasion of Abyssinia. PierreLaval, the French Foreign Minister, had, in January 1935, agreed that there were no majorFrench interests at stake in Abyssinia. In June 1935, Anthony Eden, the British Foreignsecretary, had visited Rome and proposed a deal between Abyssinia and Italy whichwould have given Italy the Ogaden region and compensated Abyssinia with a piece ofBritish Somaliland, allowing Abyssinia access to the sea. In April 1935, Britain and Francehad signed an agreement with Mussolini, which became known as the Stresa Front; underits terms, the three countries agreed to take co-ordinated action against any country

unilaterally violating existing treaties.

This agreement was prompted by Hitlers announcement that he was reintroducingconscription (March 1935). At this stage, Mussolini was very suspicious of Hitlers foreignambitions and was anxious that they might conflict with Italys influence over Austria and hisown ambitions to expand into the Balkans.

The British and French governments were very keen to maintain a common front withMussolini and to use it as a deterrent against further German breaches of the VersaillesTreaty. The Stresa Front, therefore, conditioned to a considerable extent British and Frenchpolicies towards the Abyssinian crisis as they did not want the crisis to jeopardize theiragreement with Mussolini.

Therefore, taking advantage of a fluctuating international situation, in which Italy'sfriendship had become important, Mussolini launched in 1935 a campaign the dimensionsof which resembled not so much earlier colonial wars as those in French Indo-China andAlgeria which were to follow. Almost half a million men, 450 aeroplanes, and unlimitedsupplies guaranteed the rapid and crushing victory which was required to overcomeinternational opposition and propitiate the Italian masses.

The Wal Wal IncidentThe Wal Wal IncidentThe Wal Wal IncidentThe Wal Wal Incident

Abyssinia shared a loosely defined border with the neighbouring territory to its southeast(Italian Somaliland) and the Italian military held an outpost 80 miles within the border at a

town by the name of Wal Wal or as it is known today as Ualval. Forces of the AbyssinianArmy skirmished with the Italians briefly at this outpost and as the minor conflict subsided,the Italian government demanded compensation and when it did not receive it, this minorskirmish was used as justification for mobilizing for a much larger-scale conflict.

The precursor of this incident began in 1930 when the Italians built a fort at Wal Wal, insidethe Abyssinian border that was adjacent to Italian Somaliland. Despite this breaking theagreements of friendship with the Abyssinian government, both sides maintained that therewas no aggression between the nations. However, over the next few years the Italians builtup their military presence in the area.

On November 22nd 1934 an Abyssinian force of some one thousand men arrived at the fortat Wal Wal and demanded that the fort be handed over to them. The garrison

commander refused. The risk of armed conflict seemed to die down when an Anglo-Abyssinian border commission arrived at the fort the following day. Tensions howeverremained high.

On December the 5th/6th there was a skirmish between the Abyssinian and Italian forces,both sides blaming the other for the fighting. At the end of this confrontation on themorning of December 6th, the Abyssinians had lost over a hundred of their warriors and theItalian forces had lost about thirty. The Abyssinians then fled the scene and the Italiansremained in possession of Wal Wal. Mussolini used this incident as a pretext for demandingcompensation and preparing for war against Abyssinia.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

7/31

Page 7 of 31

From the Wal Wal confrontation in December 1934 until the outbreak of hostilities some tenmonths later, there was a period of military preparation by Mussolini and despite the lipservice paid at various attempts at conciliation both within the League of Nations andoutside of it. 4

When the incident became known to the Abyssinian government, the Emperor wasinformed of the facts of the bloody battle. He was told that the Italians unexpectedlyattacked his men who were at Wal Wal, employing aircraft, bombs, tanks, guns, and machineguns. The Emperor called his foreign advisers together to ask for their help in deciding whatto do next. After consulting his advisers, the Emperor determined that his troops shouldremain at Wal Wal.

For ten days, reinforcements arrived to increase the presence of both sides but theymanaged to avoid a clash of arms, despite increasing hostility between the commandersof both sides. Early in December 1934 there was an escalation of the confrontation andalthough there may have been some misunderstandings shots rang out from one side orthe other and this was followed by heavy fusillades from both sides.

The Abyssinian machine guns, of which there were only two, were badly placed and werestill uncovered and therefore could not be fired. However, the battle seemed to be fairly

evenly matched until the Italians sent in three aeroplanes and two armoured cars. Thelatter went straight into the middle of the Abyssinians, firing their machine guns in alldirections. The Abyssinian commander fell dead as others around him did likewise; theirrifles having no effect on the armoured cars.

The aeroplanes then commenced bombing and machine-gunning the Abyssinians butfortunately the direction of the firing and the trajectory of the bombs were so inaccuratethat they were ineffective. Despite the attempted withdrawal by the Italian commander,Fitaurari Shiferra, who had very limited wartime experience, the Abyssinians, now under anew leader in Ali Nur, continued to fight regardless of the poor odds stacked against them.Finding their spears to be completely ineffective against the armoured cars, theyattempted to overturn them. Eventually the Abyssinians broke off contact and the battlehad left 107 Abyssinians dead and 45 wounded. The Italians had suffered 30 deaths and a

hundred wounded.Following this flashpoint, Britain was responsible, together with France and the USA, for thefailure to support the Abyssinia in the League of Nations when Italy began its aggressionagainst that country. Laval of France was the real problem but America under Rooseveltfollowed its pacific and isolationist programme and later refused to stop the supply of oil toItaly.

Britain could have trumped Italys war by closing the Suez Canal to stop supplies getting toEritrea and Italian Somaliland, but it didnt. Consequently, Italy defeated Haile Selassie andhis poor and almost defenceless country largely by the used of mustard gas. The successencouraged Hitler and as a result WW2 ensued.

4 Invasion of AbyssiniaPart One http://www.youtube.com/embed/mM8ZN8ZsXPgPart Two http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9OXleDJo8sc&feature=relatedPart Three http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gdRhknE6wEo&feature=relatedPart Four http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DfuJAPR4coEPart Five http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOjhTJrrjIM&feature=related

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

8/31

Page 8 of 31

The Second ItalianThe Second ItalianThe Second ItalianThe Second Italian----Abyssinian WarAbyssinian WarAbyssinian WarAbyssinian War

It was the pathetic response of Britain, France and America, together with the lack ofsupport from the League of Nations that eased the way for Mussolini to wage war onAbyssinia.

On July 6th 1935 some three months before the invasion commenced, Mussolini spoke at

Eboli, a town near to Salerno on the west coast of Italy. He allowed himself to venturebeyond prudence in an address to four Black Shirt divisions which were about to embark forAfrica. Speaking from the back of a truck, he completely exonerated Italy's soldiers of 1896for their defeat at Adowa, blaming instead the abject government in Rome at that time.

With his Fascist government in power, he assured the Black Shirt troops, that their efforts inthe field would get full support at home. Abyssinia, which you are about to conquer, weshall have totally, he shouted. We shall not be content with partial concessions, and ifshe dares resist our formidable strength we shall put her to pillage and to fire. You will havepowerful armaments that nobody in the world suspects. You will be strong and invincible,and soon you will see the five continents of the world bow down and tremble before Fascistpower. ... To those who may hope to stop us with documents or words, we shall answerwith the heroic motto of our first storm troops: Me ne freg [Trans. I don't give a damn]. Weshall snap our fingers in the face of the blond defenders of the black race. We shalladvance against anyone, regardless of colour, who might try to bar the road. We areengaged in a fight of decisive importance and we have irrevocably decided to gothrough with it. 5

Never before had Mussolini stated so publicly his naked plans for Abyssinia. This was not animpromptu outburst; copies of his speech had been sent to Fascist organizations throughoutItaly, and had reached some foreign correspondents. (Coffey, idem)

The military chief that Mussolini had appointed to command the troops in the war withAbyssinia was General Emilio De Bono. Mussolini wrote to him on 16 July 1935, in answer toa report he had sent about progress of military preparations in Eritrea,

It appears ... that the work of the High Commissioner has expanded into every field with an

intense alacrity and without intermission in order to put Eritrea into a position to face presentand future tasks. All that is necessary for the life of a population increased tenfold and agreat Italian and native army, that is roads, water, victuals, barracks, stores, hospitals and aninfinite number of other necessities, has been successfully provided in spite of difficultieswhich for various reasons were at first enormous.

One of the other necessities for which De Bono had provided, under Mussolini's orders, wasthe organization, during July, of a Chemical Warfare Service, to be called the K Service.General Fidenzio Dall'Ora who, as Quartermaster General for all Italian forces in East Africa,took charge of the formation of the "K" Service, wrote in 1937 about how it came into beingdespite the fact that both Italy and Abyssinia had signed the 1925 International Protocolagainst the use of poison gases.

We limited ourselves, Dall'Ora wrote, to the preparation of a means of defence against

chemical-bacteriological warfare, and only very partially [prepared] offensive means to beable to respond with arms equal to the enemy if he ever made use of such arms.

The Italian general staff was, no doubt, filled with uncontrollable anxiety at the possibili tythat Abyssinian, barefooted army, still using spears to compensate for a shortage of rifles,might suddenly provide itself with such a sophisticated and difficult weapon as poison gas!

5 Coffey, T M. Lion by the Tail: The story of the Italian-Abyssinian War. Hamish Hamilton, London;1974.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

9/31

Page 9 of 31

Before the K Service was formed, the Italians conducted an exhaustive study of the possibleuses of gas. One of the conclusions of this study, as Dall'Ora later explained it, was that,

The high temperatures and the vast sinuosity of the terrain produce concomitant causes ofascending air currents which make the formation of strong concentrations of gas difficult.Consequently, the offensive weapons would have had to be used with a greater density thanthat predicted for a European war; particularly for the blistering gases (which include mustardgas), aggressive action would have been predictably limited to that action coming fromdirect contact with the liquid.

According to Dall'Ora, 617,000 kilograms (680 tons) of chemical material was shipped fromItaly to Eritrea for the K Service, and was stored in three warehouses, two near Asmara andone on the plain of Ala near Nefasit, where it would be ready, if needed, to carry out themissions for which it was intended.

Although the British government failed in its duty to protect Abyssinia against the Italians,the public here at home were much surer of that need. Throughout the world, in fact,wherever people were free to speak, they were voicing anger at Mussolini's apparentintentions. The growth of moral indignation against Italy and against the men in the Leagueof Nations who were fostering Italy's designs had now become Haile Selassie's principalasset in his struggle to save his people.

The Emperor, a man of remarkable knowledge and sophistication, knew himself doomed tolead his chiefs and their unsuspecting followers into the range of modern weapons whoseferocity they could not conceive. One of the few hopes he had left was that Englandmight yet take some action, either unilaterally or in conjunction with the League; but herealized that if any help was to be forthcoming from England, it would have to arise fromthe demands of the British people, a great number of whom were now raising their voices inhis support.

Emperor Haile Selassie stood outside his palace in Addis Ababa on 2 October 1935, andaddressed the people of Abyssinia. He warned them that the time had come to fight 100,000 Italian troops had invaded Northern Abyssinia that morning.

His army consisted of around 500,000 men, many of whom were armed with nothing more

than spears, bows and arrows. Other soldiers had more modern weapons, including rifles,but many of these were from before 1900 and were badly outdated.

In general, the Abyssinian army was poorly equipped. They had about 200 antiquatedpieces of artillery mounted on rigid gun carriages. There were also about 50 light andheavy anti-aircraft guns (20 mm Oerlikons, 75 mm Schneiders, and Vickers).

The serviceable portion of the Imperial Abyssinian Air Force included three outmodedPotez 25 biplanes. A few transport aircraft were also acquired between 1934 and 1935 forambulance work. In all, the air force consisted of 13 aircraft and four pilots at the outbreakof the war.

The best Abyssinian units were the Emperor's Imperial Guard (Kebur Zabangna). These

troops were well-trained and better equipped than the other Abyssinian troops. TheImperial Guard, however, wore a distinctive greenish-khaki uniform which stood out fromthe white cotton cloak (shamma) worn by most Abyssinian fighters. Unfortunately for itswearers, the shammaproved to be an excellent target. The skills of the Rases, the generalsof the Abyssinian army, ranged from relatively good to incompetent.

On the night of 2-3 October 1935, Italian forces invaded Abyssinian territory from Eritrea andItalian Somaliland. As the appointed hour of five a.m. approached on October 3, the sunwas still hidden by eastern hills and mountains but the light of dawn had begun to revealthe shallow waters of the Mareb River.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

10/31

Page 10 of 31

Three Italian columns, each composed of an army corps, stood poised on the north bank ofthe river, at twenty-mile intervals, between Meghec on the west and Barachit on the east,ready to advance in compliance with the order issued the previous night by General DeBono. He had told them,

You have waited until this day with firm discipline and exemplary patience, the day hascome. His Majesty the King desires and Benito Mussolini, Minister for the Armed Forces, ordersthat you shall cross the frontier. (Coffey, idem)

At five a.m., native cavalry units, which formed the advance guards of each column,nudged their horses into the muddy water, emerged on the other bank, and rodesouthward into a largely treeless, broken and difficult countryside, looking for the enemy.The invasion of Abyssinia had begun.

The Italians wasted no time in bringing their bomber planes into use. From the morning ofthe 3rd October they had commenced the beginnings of a flying terror. The pilot of one ofthe airplanes above Adowa was Vittorio Mussolini, the oldest son of the Italian dictator. 6Vittorio and his brother, Bruno, had volunteered to fly in the Italian 14th Bomber Squadron,while their brother-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano, who was married to Mussolini's olderdaughter, Edda, had taken command of the 15th Squadron. Twenty two-year-old Vittorio,on his first combat mission, had led his flight across the Eritrean border, swooping so low

over the Takazze River he could see the crocodiles and hippopotamuses in the water.Within minutes they were above the conglomeration of houses and huts which constitutedAdowa. He looked for the bridge which was to be his first checkpoint. Unable to find it, hedecided simply to drop his bombs where they would do the most good into the middleof the town. But he was quite dissatisfied with his work. He later recalled,

I saw with sorrow, as will happen to me every time I miss a target that I obtained onlymeagre results, perhaps because I expected huge explosions like the ones you see inAmerican films. These little houses of the Abyssinians gave no satisfaction to a bombardier.(Idem)

By the end of the first day of the war De Bono was satisfied with its outcome. Hiscommuniqu for that day included the sinister comment:

The Abyssinians have already protested about the aerial bombardment saying that womenand children were killed. Do they expect that we will drop confetti? (Coffey, idem)

The League of Nations stated that Italy were the aggressors and imposed limited sanctions they failed to place sanctions on oil which was needed to enable the continuation ofwar. Sanctions were not increased or universally applied, even after it emerged that Italianforces were making use of Chemical weapons against civilians. Instead of imposingsanctions the British and French foreign ministers came up with the Hoare-Laval Pact. Thispact would end the war if implemented but would grant Italy large areas of Abyssinia.When news of the plan was leaked to the press there was a public outcry and both menresigned and it was withdrawn. The war continued until May 1936, when Abyssinia becamepart of the Italian Empire.

At the end of an unequal struggle, during which the Italian army used chemical weapons,Abyssinia was finally conquered at the beginning of March 1936 and annexed by theKingdom of Italy.

6 Mussolini, Vittorio. Voli sulle Ambe. Florence: Sansoni. 1937.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

11/31

Page 11 of 31

The use of Mustard Gas in the Second ItalianThe use of Mustard Gas in the Second ItalianThe use of Mustard Gas in the Second ItalianThe use of Mustard Gas in the Second Italian----Abyssinian WarAbyssinian WarAbyssinian WarAbyssinian War

Mussolinis orders to use mustard gas on the Abyssinians were not only the greatestcontroversial factor of this war but also it was the factor that turned the Abyssiniansdefence into a defeat.

The effects of mustard gas exposure include the reddening and blistering of skin, and, if

inhaled, it will also cause blistering to the lining of the lungs, causing chronic impairment, orat worst, death. Exposure to high concentrations will attack the corneas of the eyes,eventually rendering the victim blind. 7

Any area of the body which is moist is particularly susceptible to attack by mustard gas,because although it is only slightly soluble in water, which makes it difficult to wash off,hydrolysis (the splitting of a compound by water) is rapid, and occurs freely. It is importantto note here that not only are mustard gas and hemi-mustard both vesicants (blistering theskin), but the hydrolysis reaction also produces three molecules of Hydrogen Chloride,which in itself is a skin irritant. 8 When the gas, hydrogen chloride (HCl) dissolves in water itacts as a strong acid.

Mustard gas is a particularly deadly and dehabilitating poison, but its real danger is when itis used as a weapon as in the Italian/Abyssinian War in 1935/36 and also in WW1. 9

The history of its use by the Italian armed forces in the Abyssinian War is particularly horrificbecause the Abyssinian army was very largely composed of men who wore little clothing inbattle and frequently they also went barefoot.

8THOCTOBER 1935

The first record of the use of mustard gas against the Abyssinians was not in the north withDe Bonos army but in the south where General Rodolfo Graziani, commanded the Italianforces based in Italian Somaliland.

His planes had flown bombing missions against several small towns in the Ogaden desert,and his troops had occupied a few others. The Abyssinian commander in the Ogaden, Ras

Nesibu, had accused General Graziani, on October 8th of dropping mustard gas fromplanes as one of his harassment tactics. Nesibu reported,

Bursting aerial bombs blanketed a wide area with a thick yellow gas causing soldiers andnon-combatants to fall to the ground and suffer painfully. (Coffey, idem)

7 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

8 http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/motm/mustard/mustard.htm

9 MacPhee, K.E. & Barton, J.L. Polyurethane-based elastomeric material. U.S Patent 4 689 385(Cl 528-58) C08G18/327 25th Aug. 1987. CA Application 499 244 8th Jan. 1986.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

12/31

Page 12 of 31

The Abyssinian Emperor however, felt that these reports were unsubstantiated and isreported to have said that,

Let us try if we may to mitigate the inherent horrors of war by being frank and honest, andgiving our enemies credit where credit is due. Is not war horrible enough without investing itwith such horrors?

The Emperor was possibly correct that day in defending General Graziani's forces from the

charge that they had been using mustard gas. It seems that Graziani did not receiveauthorization to use gas against the Abyssinians until three days later, when Mussolini senthim a secret telegram with the following instructions:

Authorized use gas as last resort in order to defeat enemy resistance and in case ofcounterattack. (Coffey, idem)

De Bono received a telegram from Mussolini dated 14 November 1935 which in effect toldhim his time in Abyssinia was up and he was to be replaced by Marshal Badoglio. This ofcourse brought great consternation to De Bono, but it appears that Mussolini wasconcerned that the war was not moving to its conclusion as fast as he wanted it to.

Of course it is impossible to be absolutely certain to what extent De Bono's removal wasdue to Mussolini's impatience, and to what extent it was due to intrigues within the regime.

The retired Marshal Enrico Caviglia, a friend of De Bono's, blamed Badoglio, Lessona, andItalo Balbo for Mussolini's decision. Caviglia wrote in his diary:

Already in July, Badoglio had induced Balbo to support him, and then he won Lessona'ssupport. In November he went to visit De Bono in Eritrea with Lessona. There he must haveheard that success against the Abyssinians was easy, and then he managed to replace DeBono. He had been against the expedition into Abyssinia in every way; now he was full ofenthusiasm for it because it would remunerate him with easy glory. 10

This entry in Caviglia's diary, made 12 December 1936, after De Bono paid him a visit,included also some private and retrospective remarks by the embittered De Bono on thesubject:

I am happy to have left but you can't imagine how much effort was made to damage me by

my friends and my enemies. Badoglio and Lessona had worked up some infantile pretext togo there, to see whether an operation toward the Sudan was possible, as i f I were notcapable of assuring [Mussolini] that such was impossible. In order not to have to show themaround, I made myself busy, but they must have investigated the question of whether victoryover Abyssinia would be easy, and they must have assured themselves that the test wouldnot present any difficulty.

Lessona, in his memoirs, tells the story differently. He recalled that during one of themeetings he had in Africa with De Bono and Badoglio, De Bono said, I must think aboutthe war and conduct it as I can. Let him [Mussolini] think of the political problems. After all,that's his job. 11

Lessona recalled arguing with De Bono that such an attitude would be satisfactory if it werea military impossibility to win the war rapidly, but, since a quick victory seemed certain, itwas necessary in this case that arms come to the aid of politics. Either Italy wins the war ina few months, Lessona claimed to have said, or it is lost.

10 Caviglia, Enrico. Diario, aprile 1925-marzo 1945. Rome; Casini, 1952.

11 Lessona, Allessandro.Memorie. Florence; Sensoni, 1958.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

13/31

Page 13 of 31

6THDECEMBER 1935

The next serious bombing raid by the Italians occurred on the morning of 6th December1935. The Emperor had moved his headquarters to Dessie. This raid did not involve mustardgas but it did destroy a hospital.

The bombing was indiscriminate and the bombs were dropping all over the town of Dessie.Most of them, about a hundred and fifty, were incendiaries, but twenty-one high-explosive

bombs were also released, ranging in size from twenty-five to two hundred pounds. Forty ofthese bombs, mostly incendiaries, hit the Seventh-Day Adventist Red Cross hospital. Five hitthe main building in the compound, tearing the roof from the surgery. An instrument tent,contributed by a committee of Abyssinian women under the guidance of Lady Barton, theBritish minister's wife, was totally destroyed. Whole clusters of Abyssinian tukuls (roundthatched cottages) were burned to the ground. No Italian airplanes were shot down.

When the planes retired, fifty-three people were found dead and about two hundredinjured. As soon as the hospital was returned to some kind of order, the doctors thereperformed thirty amputations.

Despite attacks such as these, the battles between the troops on the ground were moreevenly matched; partly because of the terrain and partly because the Abyssinians knew

the territory better than the Italians. This obviously worried the Italian commanders and itwas from this point in December 1935 that the mustard gas war began.

Badoglio found that the Abyssinians were arriving in such numbers on his western flank thathe did not have enough conventional resources to cope with them. He believed that Itwould be useless to send infantry into the wild country west of Axum to try to cut off theAbyssinians before he reached Eritrea. The trackless terrain there was ideal for theAbyssinians and suicidal for the Italians. Only airplanes could get at the advancingAbyssinians in such country. Since the Abyssinians were now learning to spread out andtake cover, the airplanes would have to be armed with something more effective thanbombs and bullets.

Due to of the foresight of Mussolini and De Bono, Badoglio found that he did havesomething more effective, and though his country had signed an international agreementnever to use it, Mussolini, just a few days previously, on the sixteenth, had reiterated anearlier authorization to use it. 12

Badoglio could congratulate himself now for his foresight in banishing news correspondentsto Eritrea. As long as they didn't actually see what he was about to do, they wouldprobably believe him later when he denied having done it.

BOMBING OF A RED CROSS UNIT ON 22NDDECEMBER 1935

Dr. Fride Hylander, chief of the Swedish ambulance unit had come to Abyssinia under theauspices of the International Red Cross in December 1935. His Unit was based in a newencampment on the Ganale River about fifty miles from the town of Dolo in the extremesoutheast corner of Abyssinia. Dolo, on the border of Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland, was

only a few miles north of the Kenya boundary line. 13

The seventeen Swedish tents had been pitched at the edge of a sparsely wooded palmgrove, the only shade within miles, on the south bank of the wide Ganale. The camp wasclearly marked by nine Red Cross flags, three on the roofs of tents, and six more, ten totwelve feet wide, on the surrounding ground.

12 Telegram, Mussolini to Graziani, 16th December 1935.

13 League of Nations, Document c. 207.M.129, May 7,1936. Junod, 33-36. 2

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

14/31

Page 14 of 31

Very shortly after Dr. Hylander's unit had begun accepting patients on the 22nd Decemberthe area was flown over by Italian planes. After flying over the tents they then moved overthe surrounding areas and then returned from differing directions to fly over the campagain.

One, following the river bed, dropped a few bombs before it reached the camp and a fewmore after passing over it. Another, flying lower than the first opened machine-gun firedirectly above the camp, but appeared not to aim at the camp. This same plane returned

again later and made another pass at a lower altitude firing its machine-gun into theground and leaving a trail of them across the entire site. No one was injured in theseattacks and no damage was inflicted on the tents or supplies. For the next two days theplanes returned but did not attack the Unit again. (idem)

23RDDECEMBER 1935

On the morning of December 23rd, the Abyssinian commander, Ras Imru, with a sizablebody of troops, crossed the Takazze River on his way up the mountain to his advancepositions at Dembeguina Pass and Selaclaca. He had just reached the north bank nearMai Timchet when he saw several Italian planes overhead. By this time he had beenbombed so often, especially on the march north to the front, that he was not undulyalarmed. He was surprised to see, however, that these planes were not dropping bombs.

They were dropping strange containers that burst open almost as soon as they hit theground or the water, releasing pools of colourless liquid.

Before Ras Imru had time to ask himself what was happening, a hundred or so of his menwho had been splashed by the strange fluid, began to scream in agony as blisters brokeout on their bare feet, their hands, and their faces.

Some of the men rushed to the river to splash water on their burning skin, or, if they hadbreathed the ghastly fumes, to drink for the relief of their burning lungs. But since the waterhad also been polluted by the bursting canisters, these men only aggravated their injuries.Many of them, fell contorted on the banks, where they were destined to writhe, in agonythat lasted for hours before they died. A few peasants and villagers who had come to theriver for water shared their fate.

Ras Imru's chiefs and lieutenants, totally bewildered by this strange new affliction, rushed tohim for advice and help. I was completely stunned, he said later. I didn't know what totell them. I didn't know how to fight this terrible rain that burned and killed. 14

It was on this day that the Abyssinians received their first big dose of Italian mustard gas.The victims lay twisted upon the ground, without any medical care, unable to breathe thecontaminated air, and unable even to wash their wounds because of the contaminatedstream. The gas-drenched grass and shrubs around them, as well as the trees above theirheads, began to turn a sickly yellow. The barefooted companions of the afflicted men,coming to their aid, soon had to retreat as their own feet began to blister, their own lungs toburn. Marshal Badoglio had found the answer to one of his most acute problems. Heneedn't worry, for some time at least, about Ras Imru's troops dashing through the backcountry to raid the vital Adi Quala base in Eritrea. (Coffey, idem)

14 Imru to Angelo Del Boca, interview, 13th April 1965. (Angelo Del Boca - Italian historian andwriter. He specialized in the study of the Italian Colonial Empire, and the involvement in Libya,Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia during the first part of 20th century. )

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

15/31

Page 15 of 31

ITALIAN PILOTS INCIDENT ON 24THDECEMBER 1935

A completely different scenario presented on 24th December. An Italian plane was flyingover the area of Daggahbur, some 160 miles south of Harar when it developed enginetrouble and was forced to land. The plane carried a pilot and co-pilot. The latter feltapprehensive about being on the ground, unprotected from any attack by the Abyssiniansso he tried to hide in the surrounding dessert. The pilot engaged himself in trying to find away to get his plane airborne again. Whilst he was so occupied he was surrounded and

captured by either Abyssinian troops or local natives who had been affected by thebombing and machine-gunning of their flocks.

The pilot was attacked by his captors and suffered horrible injuries before he was killed anddecapitated. This was confirmed by an Egyptian who was in the area and who gave anaffidavit to this effect. This incident was used by the Italian commander, Graziani, tosupport his use of gas in the ensuing battle against the Abyssinian troops in the area.Mussolini had previously given complete and immediate authorization for the use of thebroom against foreigners.

It was Graziani who had who had been inconvenienced by the appearance of the RedCross two days earlier. He had mounted the attacks on Hylander's Unit to try and scare theSwedish medical team out of the area before they could witness the atrocity of a gas raid

on the Abyssinians.

ANOTHER BOMBING OF RED CROSS UNITS ON 30THDECEMBER 1935

The earlier attempt to decamp the Swedes was not successful and on 30th December 1935another plane attack by the Italians took place. This time the planes dropped bombs onthe Unit and Dr Hylander and two of his assistants were injured whilst they were in theoperating tent. The attack went on for about twenty minutes. Many patients were killed aswere some of the Units staff. Dr Hylander estimated that a hundred bombs had been usedin the attack.

When the planes had gone away and the level of destruction could be assessed, it wasfound that 28 men were dead and another fifty wounded. Of those wounded, fourteen

eventually died. Apart from the injuries and loss of life the Unit suffered damage to thetents and all of its motor trucks. This damage destroyed most of the medical equipment.

Later, in the debris of the attack, a number of leaflets were found that had been droppedby the Italian planes. Printed in Amharic, the leaflets stated:

You have transgressed the laws of kingdoms and nations by killing a captive airman bybeheading him. According to the law, prisoners must be treated with respect. Do not touchthem! You will consequently receive the punishment which you deserve.

The leaflet was signed "GRAZIANI," and the Italian government never denied that he wasthe author.

On the same day and again the following day, Graziani's planes also bombed andleafleted an Egyptian ambulance unit 250 miles north at Bulale. Neither he nor the Italiangovernment ever explained why, if these attacks were actually reprisals for the beheading

of the Italian pilot, Lieutenant Minniti, they were directed against foreign medical facilitiesand not against the Abyssinian troop encampments near each of these facilities.

THE MAJOR BADOGLIO OFFENSIVE IN JANUARY1936

By 19th January 1936 Marshal Badoglio was ready to launch his attack on Abyssinias largestforce. It had eighty thousand men under Ras Mulugeta and they were occupying theAmba Aradam, the very large mountain around twenty miles south of Makalle. This sitebarred the way southwards towards Quoram, Dessie and Addis Ababa.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

16/31

Page 16 of 31

History tells us that this prospective move by Badoglio was a ruse and he intended to isolateMulugetas troops from another large Abyssinian force under Ras Kassa and Ras Seyoumthat were entrenched in the Abbi Addi, Tembien region. Mussolini had been fuming at thedelays with which Badoglio had presented him and he telegraphed him to tell him to getthings moving.

Badoglio decided, at last, to move against Kassa in the west so that the Abyssinians couldnot cut off the road from Makelle north to the Eritrean border where the supply l ine ran from

the Italian bases in that country. He reported this new plan to Mussolini who approved itand in so doing reminded Badoglio that he now had an overwhelming force under hiscommand.

Mussolini ended his telegram by making it clear that his impatience had not subsided:

A word of order is not to wait placidly for the initiative of the enemy, but to confront him andcontrol him in battles which will be large or small according to the case, but victorious.

Another telegram from Mussolini was received by Badoglio on the 19th January 1936:

The manoeuvre is well conceived and will surely succeed. I authorize Your Excellency to useall the means of war I say all, both from the air and from the land.

Mustard gas had been so effective against Imru at the Takazze that Badoglio fully intendedto use it against Kassa and Seyoum; and he was happy to have Mussolini take theresponsibility for it.

Badoglio ordered a Black Shirt division, then garrisoned in the Warieu Pass about five milesnorth of Abbi Addi, to send a contingent toward Kassa's left wing in the hope of keeping itoccupied. These Black Shirt troops were not intended for any heavy fighting. That role, asusual, was reserved for the very dependable Eritrean troops to the southeast of Abbi Addi.The Black Shirt assignment, as Badoglio explained it, was, to engage the enemy, whoappeared to be in force in that area, and prevent them from leaving their positions ... [tomake] a rapid concentration with the [Abyssinian] troops distributed to the east. (Coffeyidem)

The Eritreans very quickly established contact with the Abyssinians, who had already beenharassed by aerial bombardment, thus beginning the war's first major battle, which wouldcontinue for four days and which would eventually be known as the first battle of theTembien. From morning until dusk on the twentieth, the Eritreans attacked the Abyssinianswith rifles and bayonets, slowly pushing them back until, when the sun fell, Kassa's troopshad been dislodged from one mountain and from the foothills of another. (idem)

21ST &22NDJANUARY1936

On the 21st January, all did not go well for the white Italian Black Shirt troops as they madetheir thrust south from the Warieu Pass. Better progress was made by the black Eritreantroops. Despite the bombs and mustard gas dropped by a hundred Italian planes onKassa's left-wing positions around Abbi Addi, the Abyssinians swarmed upon the Black Shirt

troops and forced them to fall back toward the pass; almost surrounding them. By the endof the day, the Black Shirts had lost 335 men, killed and wounded, during their retreat butreached the relative safety of the pass where the rest of their division was garrisoned.

There was no let up for the Italians as the chasing Abyssinians were also at the pass,engaging the garrison's outer defences. They needed to capture this pass to gain all roadsnorth. They retired for the night, convinced that a great victory was within their grasp.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

17/31

Page 17 of 31

The following morning, the 22nd January, waves of Abyssinians braved heavy bombing andgassing as they raced up the approaches to Warieu Pass to take part in a fierce siege ofthe garrison. This siege was to continue unabated during the next two days. Thebeleaguered Black Shirts, gradually running short of food, water, and ammunition, foundthemselves in ever-increasing peril as the barefooted Abyssinians, emitting hideous battlecries and spurred on by the blaring of war bugles behind them, poured forward in suchnumbers that it was impossible to stop all of them, even with machine-gun fire. Italian guncrews, with mounds of dead Abyssinians in front of their muzzles, found dozens of live ones

leaping over their fallen comrades to slash and stab with swords and spears. Gradually theItalians drew back into a tighter and tighter fortified circle as the Abyssinians overran theirouter defences. The Black Shirt division was now completely surrounded. (Coffey, idem)

The conflict was now in a position of stalemate; Badoglio tried to extricate the Black Shirts atWarieu and the Abyssinians had enormous casualties despite their successes. They alsolacked communications as they did not have a radio for either sending or reception.Italian planes managed to drop off supplies to those trapped at Warieu but there was nowater.

Italian planes that day were also dropping the heaviest concentration of mustard gasBadoglio had used to date on the Abyssinian rear positions. (No Italian commander woulddrop it into an actual battle zone because it would then injure Italian as well as Abyssinian

troops. This might explain why so many Italian soldiers have continued to disbelieve thattheir commanders used gas.) Ras Kassa afterward described vividly one of these attacks: 15

The bombing from the air had reached its height when suddenly a number of my warriorsdropped their weapons, screamed with agony, rubbed their eyes with their knuckles, buckledat the knees and collapsed. An invisible rain of lethal gas was splashing down on them. Oneafter another, all those who had survived the bombing succumbed to this new form ofattack. I dare not think of how many men I lost on this one day alone. The gascontaminated the fields and woods and at least 2,000 animals died. Mules, cows, rams anda host of wild creatures, maddened with pain, stampeded to the ravines and threwthemselves into the depths below.

A relief column finally reached the men at Warieu. Ras Kassa, who might have continuedhis assault against the exhausted Black Shirts trapped there, had now lost so many of his

own men to gunfire, bombs, and gas that he could not sustain the attack against fresh,well-armed replacements. Gradually, in the words of Marshal Badoglio, he relaxed hispressure and withdrew. (Coffey, idem)

BADOGLIO ATTACKS RAS MULUGETA ON 16THFEBRUARY1936

On 9th February 1936 Marshal Badoglio addressed a gathering of war correspondents at hisEnda Jesus headquarters near to Makalle. He spoke for a long time and eventually said tothem:

I have decided to attack Ras Mulugeta. I shall proceed as follows: Tomorrow, Monday, thetenth, the First Army Corps will transfer to positions farther forward than those it now occupies.On the eleventh, the First Army Corps and the Third Army Corps will advance in two columnstoward Antalo, south of Amba Aradam, where they will converge. I do not expect any

enemy reaction on the first day, but this will be an action on a very large scale. I shall bedirecting the movements of seventy thousand men. You will observe the battle from anobservation post near mine. Therefore, you shall see what I see. Good day, gentlemen.(Coffey, idem)

15 Haile Selassie I.La vrit sur la guerre Italo-Ethiopienne. Translated from the Amharic by MarcelGriaule. Paris: Impr. Franaise, 1936. Published also as a supplement to Vu, Paris, 1936, underthe title Une victoire de la civilisation.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

18/31

Page 18 of 31

His plan therefore was to attack Abyssinias largest army, this was estimated to be someeighty thousand men commanded by Ras Mulugeta and encamped in the caves,crevices, and foothills of the great Amba Aradam massif less than twenty miles belowMakalle. Defeat for the Abyssinians allow the Italians to gain access to the route south-ward. It would defeat the whole of the Abyssinian strategy in the north and only the armiesof the Emperor himself, now at Waldia about a hundred fifty miles below Makalle, wouldstand between him and Addis Ababa.

Badoglio had previously sent a message to Mussolini on 31st January 31 in which he wrote:

I shall concentrate the troops available here into one mobile body; with it I shall march onAntalo and Debra Aila [south of Amba Aradam). Ras Mulugeta will either accept battle orwill have to retire southward, thus uncovering Ras Kassa's lines of communication andabandoning his strong position on Mount Aradam. I hope he will decide to fight, in whichcase there will be an important battle. (Coffey, idem)

Mussolini replied on 4th February and told Badoglio: I approve the preparation and Iconfirm my certainty of victory. I authorize you to use any means. Once again, Badogliohad Mussolinis permission to use mustard gas.

On the afternoon of 12th February, the First Corps, arriving near Afgol at the south-easternfoot of the mountain, met the advance guard of a twenty-thousand-man force under the

command of Dejasmatch Wodaju, Governor of Dessie. His army advanced to meet theItalian Division and the battle of Amba Aradam finally began. It was not to last very longand the slaughter of the Abyssinians who had by then lost six thousand men was only at itsbeginning.

At dawn on the morning of 16th February, the Italian planes found Ras Mulugeta's men,consisting of more than fifty thousand defeated troops, plodding southward along theroutes toward Quoram and Dessie. That day the planes were not loaded with bombsbecause there was no danger of contaminating Italian troops, so they were carryingmustard gas, which they sprayed mercilessly upon the barefooted men below them.

Vittorio Mussolini, who took part in this exercise though he did not admit dropping gas,bragged later about the fun he had:

Whoever refuelled and reloaded first, took off first. It was a continuing contest. TheAbyssinians run fast and you can't let them disappear in smoke as they have done in the past.So, on the day of the 16th, I made two attacks. . . . Over the radio we kept gettinginformation, almost like hunting bulletins: There's a beautiful covey of fat doves at CastelPorciano, or, I advise you to go to Samra and see how full it is. To make sure, I ignored noone. I went everywhere. (Mussolini, V., idem)

The dead and the gassed (but still living) lay side by side along the roadsides south fromAmba Aradam, all equally unattended by their panicky, fleeing comrades. As the planesroared in low overhead, they spurted an oily-looking fluid which fell like light rain, causingscreams of pain within moments of contacting the skin of the Abyssinians. Those whoabsorbed heavy or even moderate doses fell quickly by the wayside, clutching their limbsor their faces, gasping for breath as the lethal gas entered their lungs. Those who were

sprayed by only a few drops cried out like the others but kept moving in the hope that theymight avoid the next shower as more planes approached. (Coffey, idem)

For three more days, Italian planes sprayed mustard gas and machinegun bullets on thefleeing Abyssinians until the bodies lay in sprawling piles along the route and an estimatedfifteen thousand men had been added to the six thousand casualties of the Aradambattle. By evening of the nineteenth, the army of Ras Mulugeta no longer existed. (Coffey,idem)

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

19/31

Page 19 of 31

DEATH OF RAS MULUGETA ON 19THFEBRUARY1936

On 19th February 1936 and to avoid any further bombing and gassing during his retreat, RasMulugeta travelled along a circuitous route towards Mai Chew. After five days he met upwith two other retreating bodies of Abyssinians led by Ras Kabede and Major Burgoyne.

As they moved towards their destination, Kabede led the party and he was followed byBurgoyne and Ras Mulugetas son, Major Tadessa Mulugeta. Without warning they were

attacked by Italians planes and a bomb, landing between Burgoyne and TadessaMulugeta killed them both. In the ensuing battle that had been enjoined by snipers fromthe hills, Ras Mulugeta was also killed.

1ST MARCH 1936

The Emperor was now feeling desperate as he heard news of defeats in several quarters.On 27th February he struck camp at Waldia and moved north to Cobbo. By 1st March hehad reached Alamata which was about fifteen miles from his destination at Quoram.

All along his route he had been passing his own troops marching northward. Now hebegan passing Mulugeta's bombed, gassed, and almost insensible men stragglingsouthward. The reports of Red Cross doctors in the area indicate some of the scenes he

had to witness.

Dr. George Dassios, a Greek volunteer, had seen his first gas patient in January, at Waldia.The man had been brought from Quoram, where he was a victim of an air raid. Dr. Dassiosrecalled:

Seeing this first victim, I could not believe it, though the signs were there difficultbreathing due to gas in the lungs and blisters on the skin; but because it had taken a con-siderable time to get the man from Quoram to Waldia, I thought he might be suffering fromsomething else. Within a few days, more victims came and I realized the Italians wereactually using mustard gas. From that time on, there was a continuous increase in the flow ofvictims. During January, I treated more than fifty. 16

In February, Dr. Dassios moved north toward the front. Here is his description of the trip:

Going to Quoram, one passes a small lake, beautiful and picturesque. The water wasyellowish and all around the shore lay bodies of men and animals more animals than men.During that period I was so hungry and had so many things on my mind I can't rememberexact dates, but it was after the battle of Amba Aradam. After that battle, thousands of mencame our way. There were so many we could do nothing for them. There were so many wecouldn't count them. We couldn't even put up tents at treatment centres during thedaytime. The planes were still attacking. After five p.m. we would put up our tents and dowhat we could. I asked one patient if he had seen the plane (which attacked him). He said,No, I think it was the devil pulling someone by a string. The gas victims I saw (after AmbaAradam) must have numbered around two thousand. (idem)

Dr. John W. S. Macfie 17 of the British Red Cross unit, who had also treated a few cases ofgas burns in Waldia, arrived at Alamata on February 29th, the day before the Emperor

passed through en route to Quoram. Dr. Macfie reported that he and the other men in hisunit were not fully prepared for the sight that greeted us on driving into the camp whichother members of the unit had built at Alamata. He went on to write:

16 Dr George Dassios, interviewed, Addis Ababa, 17 February 1972.

17 Macfie, John W. S. An Ethiopian Diary. Liverpool; Liverpool University Press, 1936.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

20/31

Page 20 of 31

In a corner on our right under a tree, we saw the outpatients collected there, scores ofthem, and Chandler (Warrant Officer E. D. Chandler, another member of the unit) and hisdressers were feverishly covering them with bright yellow pieces of gauze and rolls and rollsof bandages. Somewhere in the middle of the group stood a great pail of yellow fluid picric acid solution (the only medication available for treating the burns).

On closer inspection, the patients were a shocking sight. The first I examined, an old man, satmoaning on the ground, rocking himself to and fro, completely wrapped in a cloth. When Iapproached he slowly rose and drew aside his cloak. He looked as if someone had tried to

skin him, clumsily; he had been horribly burned by mustard gas all over the face, the backand the arms.

There were many others like him; some more, some less severely affected; some newlyburned, others older, their sores already caked with thick, brown scabs. Men and womenalike, all horribly disfigured, and little children, too. And many blinded by the stuff, withblurred, crimson apologies for eyes. I could cover pages recounting horrors, but what wouldbe the use?

Early the next morning, a Sunday, the Emperor arrived in Alamata with his entourage just asthe Italian airplanes began the day's bombings. Like the thousands of his soldiersencamped along the road and on the surrounding plains, he retired into the hills for safetyduring the day. When bombing time came, the Abyssinian troops, accustomed to it now,swarmed up the hillsides to find shelter, leaving their folded tents and personal effects

hidden from the planes under trees.

In the afternoon, when the bombing receded, the Emperor, again like all his soldiers,emerged from shelter and resumed his journey to Quoram. Although it was only a littlemore than fifteen miles north of Alamata, the road, which followed a winding, hilly trail, wasonly partly finished. It was also overcrowded with troops going both ways, arriving from thesouth and retreating from the north. The daily bombings were almost constant. It tookHaile Selassie three days to reach Quoram, a small village within a circle of big hills aboutfive miles south of Lake Ashangi. (Coffey, idem)

Captain John Meade, the American military attach, who was at Quoram when theEmperor arrived, found him obviously much depressed but quite pleasant in his manner. Bythis time, the remnants of Mulugeta's army had circulated fearsome rumours about the

strength of the Italian forces and the speed with which they were driving southward. TheEmperor immediately sent a party of men northward on a reconnaissance mission todetermine the exact location of the enemy. Then he settled into one of the three largecaves which had been set aside as his headquarters and began the tedious details ofmoulding his rabble-like followers into a battle-ready army.

THE SECOND BATTLE OF TEMBIEN

Meanwhile, Marshal Badoglio, having routed Ras Mulugeta and destroyed his army, wasnow able to turn his two hundred thousand well-equipped and battle-seasoned men uponthe sixty to seventy thousand Abyssinians left in the north under the commands of Kassa,Seyoum, and Imru. He gave his attention first to Kassa and Seyoum, whose combinedforces, about thirty thousand men, were still encamped near Abbi Addi and the Warieu

Pass, where the first Battle of Tembien had taken place, about thirty miles west of Makalle.

On February 16th and 18th, determined to give the Abyssinians no respite, Badoglio issuedorders disposing his troops for a second Battle of Tembien. He sent his First Army Corps fromAmba Aradam to Amba Alagi, and they captured this mountain without opposition onFebruary 28th, thus closing the best and one of the few possible routes of retreat for Kassaand Seyoum. He then sent his Third Army Corps from Amba Aradam southwest into theTembien, whence this force could advance northward toward Abbi Addi as one prong of apincer movement. The other prong would be the large Eritrean Corps, which he hadalready concentrated just north of the Kassa-Seyoum positions, in the area of the WarieuPass.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

21/31

Page 21 of 31

Badoglio was feeling much more confident now. When he addressed the warcorrespondents at his Amba Gedem observation post after the Battle of Amba Aradam, hewas, in the words of one reporter, extremely animated, in high good humour, and lookingtwenty years younger. He had become so certain of the ascendancy as a result of hisgreat victory that when Mussolini suggested to him the possible use of bacteriologicalwarfare, he had advised against it. He must have felt that as long as he had enoughmustard gas, he could afford to show how humane he was by forgoing even more hideousweapons. In a February 20th telegram, Mussolini acceded to his advice. I agree with

what Your Excellency observes about the use of bacteriological war, the Duce wrote. Noother references to the subject have been found. Badoglio launched his drive to annihilateKassa and Seyoum in the early hours of February 27th. (Coffey, idem)

The second battle of Tembien ended without a major confrontation, but with a flight asdisastrous as any battle could have been. In the southern Tembien and Seloa regionsduring the following days, the Italians found a wealth of targets for their mustard gas as thebewildered Abyssinian soldiers struggled southward through forests, rivers, plains, canyons,and mountains, trying to escape the burning rains which fell upon them from the airplanes'bomb racks.

Badoglio was now able to take up battle with Ras Imru who had defeated him in their firstengagement and who had been subjected to the first use of mustard gas by the Italians.

Fortunately for Badoglio, he did have the means at his disposal to cover up his earliermistakes in battle strategy. Once again at the end of this battle, which was to becomeknown as the Battle of Shire, he sent his airplanes against the Abyssinians, whose retirement,he later reported, very quickly turned into a disorderly rout.

Badoglio reported that:

On reaching the Takazze fords, difficult enough in themselves because they were sunkbetween high, steep and thickly wooded banks, Ras Imrus passage was rendered evenmore critical by continued air activity. In addition to the usual effective bombing andmachine-gun fire, small incendiary bombs were used to set on fire the whole region aboutthe fords, rendering the plight of the fleeing enemy, utterly tragic. Our aerial activity may besummed up in the following figures: 80 tons of explosives were dropped, and 25,000 rounds ofmachine-gun ammunition were fired.

Once again Badoglio failed to credit his most useful ally mustard gas. Italian pilots whobombed, strafed, gassed, and burned the area of the fords between the third and the sixthof March later reported seeing, vast numbers of Abyssinian dead on the north bank of theTakazze and countless bodies of men and beasts floating on the river. Later, when Italianground troops crossed the Takazze, they found the area, littered with thousands of corpsesin an advanced state of putrefaction.

Ras Imru, describing his flight many years later, said,

I succeeded in leading some ten thousand of my men across the river to safety, but theywere so demoralized that I could no longer hold them together. Day by day my ranksthinned out; many were killed in the course of air attacks, many deserted. When at last Ireached Dashan (about fifty miles south of the Takazze), all that remained of my army was

my personal bodyguard of three hundred men.

Only one Abyssinian fighting force now stood between the Italians and Addis Ababa theEmperor's army at Quoram, less than thirty miles south of Badoglio's First Army Corps atAmba Alagi. (Coffey, idem)

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

22/31

Page 22 of 31

HITLER TAKES COURAGE FROM THE FASCIST MUSSOLINI

In Berlin on 1st March 1936, Hitler summoned his Minister of Defence, General Werner vonBlomberg, and told him that despite the fact that Germany was not ready for war and didnot have sufficient armaments available and that its army would not be up to fightingagainst the French, he had decided to defy the Versailles Treaty by reoccupying thedemilitarized left bank of the Rhineland. He was aware, however, that the French couldstop him if they decided to march into the Rhineland and he reserved the right in such an

event, to decide on any military countermeasures. 18

As several German generals testified many years later at Nuremberg, the onlycountermeasure Hitler contemplated in case the French resisted was an immediateGerman retreat. It is clear that Hitler had already learned so much about France andEngland by studying Mussolini's methods of bluffing, bullying, and manipulating them thathe did not believe the French would make any move which might bring on a war.

At dawn on 7th March 1936, whilst German generals quaked in fear, a skeleton force ofthree German battalions marched timidly across the Rhine River bridges into thedemilitarized zone. In the days that followed, the French and British filled the air withquerulous complaints, but not one French soldier set foot in the Rhineland to resist this firstaggressive move the German army had made since 1918; this first military foray of Adolf

Hitler's career. (Coffey, idem)

ANOTHER UNPROVOKED ATTACK ON A RED CROSS UNIT

Early on 4th March 1936, Dr John Melly, the commanding officer of a British Red Cross Unitthat had just been placed near to Quoram, was getting ready for the work of the day. TheUnit was a thirty-one tent camp that was marked with two Red Cross ground flags as well asother flags on poles (one Red Cross, the other a British Union Jack. The camp was wellaway from any Abyssinian troops. Although new, the Unit had been inspected from theair by several Italian planes during the short time it had been erected.

Dr Melly and his colleagues had some twenty-one surgical operations to perform that dayand there were more than a hundred patients in the Unit who had suffered from gassing.

As he started to operate on his first patient around noon he heard a plane approaching atlow altitude and before anyone could take precautions it dropped a bomb very close tothe tents. Dr Melly took the necessary surgical precautions and halted the operation, eventhough the patient was suffering from peritonitis.

More bombs fell and the operating tent was inundated with falling earth from theexplosion. The team sought the protection of cover away from the tents and had toabandon the anaesthetised patient. Another attack sent more bombs in their directionand one of Dr Mellys assistants was injured.

The raid lasted about half an hour and when the doctors returned to the camp they foundthe site strewn with wreckage amongst which were dead and wounded. After the raid wasover it was found that five Abyssinians had been killed and several others woundedincluding the patient who was on the operating table.

The operating tent and two ward tents were seriously damaged; a third tent was burned.Five other tents were destroyed as well as a large amount of medical equipment. Anassessment showed that at least forty bombs had been dropped, one of which gained abulls eye on the Red Cross ground flag.

18 Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960; London:Seeker & Warburg, 1960.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

23/31

Page 23 of 31

Later reports indicated that the planes number was S62 and that Vittorio Mussolini was itspilot. The Italian government tried to appease complainants by saying that their planeshad previously been fired upon as they passed over Red Cross camps.

It seems that the agenda behind the attacks was to frighten the Red Cross out ofAbyssinia so that the Italian atrocities would not get the first hand reports that wereproduced by that organisation.

The International Red Cross sent out an inspector so that he could see for himself what theRed Cross Units had to tolerate whilst undertaking their humanitarian work. 19 The Inspector,Dr Marcel Junod, arrived at Quoram and was assisted to get to the mountainside cavesthat were the headquarters of Haile Selassie by riding on a mule that had been sent by theEmperor. As they progressed on their two-mile journey, the doctor noticed a pervadingsmell like horse-radish and asked his guide what it was. He was informed that it was theresidue aura of mustard gas that the Italian planes spread over the area.

Dr. Junod was able to have his first hand experience of what the Abyssinians and the RedCross workers had to tolerate. His Abyssinian guide explained that the gas was beingspread in two ways. It was either dropped in bombs which scattered it over an area of twohundred yards or more or it was sprayed it from low-flying planes so it fell like rain. He toldJunod:

They know our soldiers go barefoot," and in that way contract terrible burns. In addition, ourmules die from nibbling grass and leaves contaminated with the liquid.

The plane that had brought Junod and Count van Rosen (his planes pilot) had beencamouflaged in a primitive way and this allowed it to be seen in outline from above. Thefirst of the days Italian bombers arrived and Junods plane and that of the Emperor musthave been clearly visible to the Italian pilots and they made a beeline for them both anddropped their bombs. The Emperors plane was destroyed by a direct hit but that of theRed Cross team was miraculously missed. The pilot and Junod desperately tried to reachtheir pane so that its Red Cross marking could be seen.

As they got nearer to the plane it became obvious from the odour and their stinging eyesthat the Italians had mixed mustard gas bombs in amongst those that were high explosive.

The pair managed to strip the flimsy camouflage from their plane just as three Italian fighterplanes approached. They fired their machine guns at the remaining plane and hit the fueltanks that then allowed all of it to flood out. They left the scene to quickly return to thecaves in the hope of telephoning Geneva to try and get the planes called off. As theyonce again got up the mountainside they looked back to see that their plane was now apile of burning wreckage.

As they got near to the Emperors caves they heard wailing that caused them to pale androunding the last bend they came across what must have been thousands of Abyssiniansstretched out in agony under the trees. The sound that they heard was the commonAbyssinian cry for help or mercy; Albeit! Albeit! Albeit! (Coffey, Idem)

As they approached these men, they could see, horrible, suppurating burns on their feet

and on their emaciated limbs. The gas could not, of course, be blamed for theiremaciated limbs. Most Abyssinian soldiers were thin and underweight because of thechronic food shortage. As Dr. Junod walked through this writhing, piteous mass of men, hehad to endure his frustration at being unable to relieve their pain.

19 League of Nations Document C201, M126, 9 May 1936, photos 1-25, Appendix 9.

-

7/23/2019 The Mustard Gas War

24/31

Page 24 of 31

The two Red Cross units under his supervision in the area, the Dutch and the damagedBritish, were already treating as many gas cases as they could handle. But if Junodexpected this suffering multitude at his feet to make impossible demands upon him, hesoon learned otherwise. It was not the white medical men, whose skills they scarcely knew,that they begged for help. Their voices were raised toward the cave of their Emperor, whowas their only hope, but who could do no more than pace the floor, as helpless as they,listening to their cries.

After hearing these cries until he could scarcely endure them, Haile Selassie wrote his wife,Empress Menen, in Addis Ababa, the first letter in which he had showed any indication ofdespair. It was horrible, he said, to hear the screaming of his men during the night. Oldfriends had come to see him whom he no longer recognized because of the terrible bumson their faces. He could bear it no longer, he told her. (Coffey, Idem)

He continued to bear it, however, because he was acutely conscious of his role and dutyas Emperor of Abyssinia. The Lion of Judah must confront his enemy in the open field. Hehastened to do so, ordering his chiefs to prepare their men for battle. He now had at hisdisposal about thirty thousand men, including his own Imperial Guard, who wereAbyssinians best soldiers. But the Guard was comprised of only six infantry battalions plus abrigade of artillery. Most of the thirty thousand in this last-ditch Imperial army were un-trained and nondescript.

Although the Emperor wanted to make an early attack on the Italians his powerful chiefsargued for a delay to consider the implications. This did not please Haile Selassie and heagain pressed for an immediate advance on the Italian troops at Mai Chew. Days passedwhilst the Emperor and his chiefs continued their discussions. The Italian planes continuedto bomb his troops. Haile Selassie sent a telegram to his wife explaining what washappening and what he was proposing to do. This telegram was intercepted by theItalians.

By this time Mussolini was beginning to believe that his conquest of Abyssinia was almostcomplete. He recklessly sent a message to Badoglio:

Any Red Cross Unit which might be found at Gondar and any flag which might be pulledout at the last moment (you) should go ahead and shoot at it, but avoid damaging the

British Red Cross if any exists there.

Aware that he had already tried British patience beyond reasonable limits, and that theycould still thwart him at the edge of victory by closing the Suez Canal, he apparently feltthe time had come to begin handling them with at least a small degree of prudence. Butthere was still no need for prudence in his treatment of anyone else, especially theAbyssinians. On the 29th March 1936, he sent Badoglio the familiar endorsement:

Given the enemy methods of war, I renew the authorization for the use of gas at any timeand in any measure. (Coffey, Idem)