Mustard procedure

Transcript of Mustard procedure

Br Heart J 1994;72:85-88

Transcatheter stent implantation for recurrent

pulmonary venous pathway obstruction after theMustard procedure

Martin C K Hosking, Kenneth A Murdison, Walter J Duncan

AbstractA 5 year old boy presented with obstruc-tion of the pulmonary venous pathwayfour years after the Mustard procedure.A successful balloon dilatation ofthe pul-monary venous pathway was performedbut the benefit was transient. Placementof a 10 mm balloon expandable intravas-cular stent across the recurrent stenosisresulted in complete relief ofthe obstruc-tion with prompt resolution ofthe clinicalsigns. The delivery system was modifiedto facilitate stent delivery.

(Br Heart 1994;72:85-88)

Paediatric experience with transcatheterplacement of endovascular stents for residualstenosis has expanded from the initial studiesof systemic vein and pulmonary artery dilata-tion to include recent reports of stenting ofthe ductus arteriosus, aortopulmonary collat-erals, and postoperative coarctation of theaorta.' 2 After the Mustard operation for trans-position of the great arteries, pulmonaryvenous pathway obstruction is a less commonbut more severe complication than systemicvenous pathway obstruction.3 In an attempt toavoid surgery with its attendant high operativerisks balloon dilatation has shown some

benefit, although restenosis often occurs.4

We report the successful percutaneousintravascular stenting of recurrent pulmonaryvenous pathway obstruction after a previouslysuccessful balloon dilatation. We discuss thetechnical modifications found useful in facili-tating stent placement in locations with diffi-cult access.

Division ofCardiology, ChildrensHospital ofEasternOntario, Ottawa,CanadaM C K HoskingK A MurdisonW J DuncanCorrespondence to:Dr Martin C K Hosking,Division of Cardiology,Childrens Hospital ofEastern Ontario, 401 SmythRoad, Ottawa, Ontario,Canada K1H 8L1.

Case reportThe 5 year old patient was diagnosed in theimmediate newborn period with atrioventric-ular concordance, ventricular arterial discor-dance (d-transposition of the great arteries),and intact ventricular septum. A balloon atrialseptostomy was performed on the first day oflife, then a Mustard procedure at threemonths.

During the next five years his clinicalcourse was characterised by persistent deteri-oration in oxygen saturation associated withan increasing requirement for diuretics andsupplemental oxygen to maintain adequateoxygenation. Serial precordial Doppler andcross sectional echocardiography showedevidence of progressive pulmonary venous

pathway obstruction reaching a maximumflow velocity of 2'0 m/s associated with astenosis measuring 2-3 mm in diameter.Right ventricular dysfunction was a persistentechocardiographic finding associated with anincrease in left ventricle dimension inresponse to the rise of pulmonary arterialpressure secondary to the pulmonary venousinflow obstruction. A significant systemic topulmonary venous chamber baffle leak mea-suring 5 mm x 4 mm with right to left shuntingwas seen by Doppler colour flow mapping andcontributed to central cyanosis. Serial chest xray films showed persistence of cardiomegalywith increasing evidence of pulmonary venouscongestion.To avoid the risks of surgical repair in a

patient with impaired right (systemic) ventric-ular function, the initial therapeutic inter-vention included balloon dilatation of thepulmonary venous pathway obstruction witha 12 mm x 2 cm balloon (Meditech,Watertown, MA, USA) along with catheterocclusion of the baffle leak with a 17 mmPDA Rashkind occluder device.5 After this,transoesophageal Doppler assessment withsimultaneous haemodynamic correlationshowed a reduction of the pulmonary venousoutlet gradient to 6-8 mm Hg with anincrease in diameter from 3 mm to 7 mm.Clinically there was a considerable improve-ment with reduction in oxygen requirement.Diuretic treatment was no longer required asthe pulmonary oedema seen previouslycleared.The benefit was transient and seven

months after catheterisation, his clinical statehad once again deteriorated with increasedoxygen and diuretic requirements as before.Careful imaging and Doppler colour flowmapping again showed a velocity of 2 m/sacross the pulmonary venous baffle with arecurrence of the stenosis measuring 3-4 mmin diameter. As the previous catheterisationhad shown the distensibility of this bafflestenosis, to avoid further restenosis and main-tain an optimal passage for pulmonary venousflow we decided to implant an intravascularstent across this area of narrowing.

CATHETERISATION PROCEDUREInformed consent was obtained and the pro-cedure was performed under general anaes-thesia. A transoesophageal biplane 5 MHzechocardiographic probe was placed beforethe start of the catheterisation and left in situthroughout. An arterial catheter was placed bya standard percutaneous approach and the

85

Hosking, Murdison, Duncan

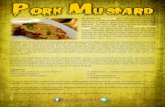

Figure 1 (A) Angiogram(anterior to posteriorprojection) of the proximalpulmonary venous atriumshowing position andseverity of the baffle neckobstruction (arrows). (B)Anterior to posterior viewshowing the non-inflatedstent (arrows) in positionacross the baffleobstruction. Note thetortuous catheter coursewith the guide wirepositioned in the left lowerpulmonary vein. Thedelivery sheath has beenretracted before inflation.The 17 mm Rashkindoccuder device is inposition across a previoussystemic to pulmonaryvenous baffle defect (openarrow) and was used tohelp position the stentoptimaly before inflation.(C) Similar view as beforeshowing the inflated stentin position. Note how thestent has attained the curveof the superior baffle aspect(arrows). ruPV, rightupperpulmonary vein;d PVA, distal pulmonaryvenous atrium; p PVA,proximal pulmonaryvenous atrium.

patient was heparinised with 100 U/kg. Thediagnosis ofpulmonary venous outlet obstruc-tion was confirmed by haemodynamic mea-surement by pullback tracing over the stenoticarea and angiographic assessment (right ante-rior oblique and lateral projections).A retrograde arterial approach was used to

gain access to the pulmonary venous atrium.An end hole balloon catheter (ArrowInternational, Reading, PA, USA) wasdeflected from the morphological right ventri-cle across the right atrioventricular valve andpositioned within the distal pulmonary venousatrium. With the aid of a steerable guide wire(Hi-Torque Floppy, Advanced Cardio-vascular systems, Temecula, CA, USA) thearea of stenosis was crossed and measuredhaemodynamically and with angiograms todelineate it (fig 1(A)). A stiff 0-032 inchAmplatz guide wire was positioned in the leftlower pulmonary vein and the stent deliverycatheter was manoeuvred over this. A 2 cmPalmaz stent (Johnson and JohnsonInterventional Systems) carefully secured on a

10 mm x 3 cm balloon dilating catheter(Optiplast, Mississauga, Ont) was successfullyplaced across the area of baffle stenosis. Thefinal stent diameter was 10 mm (fig 1 (A-C)).Due to the tortuous route leading to thebaffle stenosis, a modification in the standard

delivery technique was used to avoid thepotential for kinks to develop in the 7 Frenchdelivery sheath once the dilator was removed.After placement of the sheath and dilator sys-tem within the abdominal aorta, the dilatorwas replaced with the stent/balloon dilatingcatheter. Ensuring that only the tip of thiscatheter extruded from the sheath, thus actingas a smooth guiding tip for the sheath whilestill protecting the stent, the entire system wasmanoeuvred over the guide wire and posi-tioned across the area of stenosis. Even withthe use of a stiff 0-032 inch Amplatz guidewire careful alternating traction and advance-ment of the wire was requiured for the catheterto traverse the trabeculated right ventricle andmake the final curves across the baffle steno-sis. Once in an optimal position, the sheathwas withdrawn and the stent deployed in thestandard method. No complications occurredduring the stenting procedure.

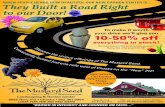

Before stenting, both angiography andtransoesophageal echocardiography showed adiscrete wedge of tissue projecting into thevenous channel from the superior atrial wallresulting in a minimal pulmonary channel of4 mm (fig 2A). Haemodynamic measure-ments showed a mean gradient of 12 mm Hg,with a maximal Doppler velocity of 1-9 m/sand non-laminar colour flow Doppler. Afterstent placement indwelling transoesophagealechocardiography clearly showed the stent inan optimal position with a widely patentlumen of 10 mm diameter and laminar unob-structed colour flow Doppler across the openstent (maximal velocity of 0-8 m/s). To avoidpotentially dislodging the stent a pressurecatheter was not placed across the area andthe wire and catheters were removed withoutcomplication. The patient was maintained on aheparin infusion (20 U/kglh) for 24 hoursthen subsequently placed on aspirin (8mg/kg/day).

Since the procedure a dramatic clinicalimprovement has been seen. His chest x rayfilm has cleared, there is no further need fordiuretic treatment, and oxygen saturationsare above 95% in room air. His activity leveland general demeanour have dramatically

86

Transcatheter stent implantation for recurrent pulmonary venous pathway obstruction after the Mustard procedure

Figure 2 (A) Transoesophageal echocardiogram in the longudnal plane. There is a discrete 3-4 mm diameter irregular stenosis (arrows) betweenproximal (p) and distal (d) pulmonary venous atnum (PVA). An additional pulmonary vein (large arrow) is seen to enter the d PVA.(B) Transoesophageal echocardiogram in the longitudinal (L) plane showing the stent in position across the stenosis. Note iow the stent has contact withthe superior atrial wall and baffle (arrows) for all of its length, thus providing optimal stability. (C) Doppler spectral analysis offlow after stentimplantation.

improved. Follow up Doppler studies haveshown persistent relief of the baffle obstruc-tion with flow velocity <1 mIs.

DiscussionIn t-his report we describe the successful appli-cation of percutaneous intravascular stentingfor the treatment of a persistent pulmonaryvenous pathway obstruction. Balloon dilata-tion of a pulmonary venous pathway obstruc-tion has been shown to be an efficacioustherapeutic option for this difficult complica-tion of both the Mustard and Senning repair.There is, however, a strong tendency for thestenosis to reoccur4 and these patients presenta high risk at reoperation.3 Intraluminalstents, when inflated, expand with a highresistance to radial collapse thus making themoptimal devices for maintaining patencyacross the distensible venous baffle. One con-sideration in whether to stent for baffleobstruction is the length of contact betweenthe baffle and the superior atrial wall. Thisshould be sufficient to allow the stent to haveadequate atrial wall to baffle contact so as tomaintain a stable position when inflated. Caremust be made to ensure that, when position-ing the stent, the origin of the right upper and

right lower pulmonary veins will not be dis-torted on inflation (fig 1(A)), which couldinduce a pulmonary vein stenosis. In this case,placement of the stent across the area ofrestenosis resulted in a widely patent 10 mmchannel with no evidence of stenosis by bothimaging and Doppler colour flow mapping.This was associated with a considerable clinicalimprovement, although close follow-up will berequired. As the stent is within the systemiccirculation we have decided to continueantiplatelet treatment indefinitely, rather thanthe usual six months for devices placed withinthe pulmonary circuit or systemic veins.

For pulmonary venous pathway balloondilation, balloon to stenosis ratios of three tofour have been recommended.4 As the stentmaintains a non-collapsible state after deploy-ment a much smaller balloon to stenosis ratiocan be used, thus reducing the potential forarterial damage. A 1 cm diameter stent waschosen as it was considered that this wouldallow unimpeded pulmonary venous bloodflow. It was recognised that with growth itwould be unlikely that a 10 mm pathwaywould allow unimpeded flow for life. Furtherdilatation to 12-14 mm would have beenoptimal, but over expansion would result inshortening and distortion of the 2 cm medium

87

Hosking, Murdison, Duncan

Figure 3 Angiogram(lateral projection) duringstent inflation showing theanterior position of theductal occluder devicerelative to the area ofstenosis.

Palmaz stent with the potential for suboptimalpositioning on implantation. After completeendothelialisation, the stent will be moresecure and not easily displaced. O'Laughlin etal have shown the ability to further dilateimplanted stents.1 Should flow velocityincrease over time an attempt at further infla-tion to 12 mm would be a reasonableapproach. Close follow up of these patients ismandatory.

Complete endothelialisation of the ductaloccluder device occurs within three to sixmonths of implantation. A device that isplaced in too posterior a position along thebaffle may impinge on systemic and pul-monary venous return. Also it is possible thatextension of the endothelialisation processmay augment any intrinsic pulmonary venous

pathway obstruction. In this case the anteriorlocation of the occluder device relative to theinflated stent (fig 3) makes it unlikely that thiswould contribute to restenosis.Due to the tortuous route required to posi-

tion the stent across the baffle stenosis and as a

result of previous experience, we have modi-fied the placement technique from that previ-ously described. In previously described

reports after the sheath and dilator have beenpositioned across the area of stenosis the dila-tor catheter is removed leaving the guide wireand empty sheath in place.' On removal of thedilator catheter there is a tendency to developkinks within the sheath especially in thosecases where the catheter is needed to negoti-ate acute angles. As a result, when attemptingto pass the balloon dilatation or stent catheterthrough the sheath it can become caught inthe kink, causing displacement of the stentfrom the balloon. Alternatively, the stent maybe unable to traverse the kink thus necessitat-ing the replacement of the dilator and furthercatheter manipulations to straighten out thedelivery sheath. With the stent deliverycatheter as part of the sheath and manoeuv-ring the entire complex as a unit obviates thedevelopment of the sheath kinks. This greatlyeases stent placement in small infants and instenoses with difficult access. As the sheathdoes not require flushing this is especiallyadvantageous for cases needing stent place-ment in the systemic circulation.

In conclusion, this case shows that persis-tent obstruction of the pulmonary venous out-let can be successfully relieved with the use ofa percutaneous intravascular stent and furtherexpands the paediatric applications of thisnew therapeutic method. The long termpatency of such a device within the pulmonaryvenous system remains unknown, althoughlarge diameter stents in high flow venouschannels have previously shown optimalpatency rates.6 The modifications of the deliv-ery technique that we described have facili-tated the technical aspects of stent placement.

1 O'Laughlin MP, Slack MC, Grifka RG, Perry SB, LockJE, Mullins CE. Implantation and intermediate termfollow-up of stents in congenital heart disease.Circulation 1993;88:605-14.

2 Redington AN, Hayes AM, Ho SY. Transcatheter stentimplantation to treat aortic coarctation in infancy. BrHeartJ 1993;69:80-2.

3 Stark J. Reoperations after Mustard and Senning opera-tions. In: Stark J, Pacifico A, eds. Reoperations in cardiacsurgery. London: Springer Verlag, 1989:187-207.

4 Coulson JD, Jennings RB Jr, Johnson DH. Pulmonaryvenous atrial obstruction after the Senning procedure:relief by catheter balloon dilatation. Br Heart J 1990;64:160-2.

5 Hosking MCK, Alsheri M, Murdison KA, Teixeira OHP,Duncan WJ. Transcatheter management of pulmonaryvenous pathway obstruction with atrial baffle leakfollowing Mustard and Senning repair. Cathet CardiovascDiagn 1993;30:76-82.

6 Chaitelain P, Meier B, Friedli B. Stenting of superior venacava and inferior vena cava for symptomatic narrowingafter repeated atrial surgery for D-transposition of thegreat vessels. Br Heart J 199 1;66:466-8.

88