Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas: a congestive myelopathy - Brain

Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula: a treatable cause of myelopathy

Transcript of Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula: a treatable cause of myelopathy

Practice

CMAJ • May 6, 2008 • 178(10)© 2008 Canadian Medical Association or its licensors

11228866

The case: A previously healthy 46-year-old man, who works as a stand-ing forklift operator, presented to anemergency department with a 1-dayhistory of bilateral leg “soreness” andnumbness in his right leg ascendingto his groin. Seven-months beforewhile lifting a heavy box, he had expe-rienced sudden pain in his right but-tock and leg that was treated withanti-inflammatory medications andrest. Subsequently, he began to expe-rience bilateral leg fatigue with mod-erate activity, occasional nocturnalurinary incontinence, stiffness of gait

with dragging of the right leg and legweakness elicited by hot baths(Uhthoff phenomenon). The patientalso reported a 12-month history ofintermittent sharp left costal pain thatfollowed a dermatomal distribution,from just below his left nipple to hismid back. The pain became worsewith deep inspiration.

On physical examination, the pa-tient was oriented and cooperative,and his vital signs were normal. The re-sults of an examination of the cranialnerves and upper extremities were nor-mal. He was able to stand, and hewalked with a spastic gait and appre-hension of falling. The patient had anormal range of spine movement withno tenderness to palpation over thelength of the spine. A passive straight

leg raise did not elicit pain. Muscletone was increased in both of his lowerextremities. Power in his iliopsoas,quadriceps and hamstrings was slightlyweak, and he had normal power in hisgastrocnemius, tibialis anterior and ex-tensor halluces longus bilaterally. Thepatient’s deep tendon reflexes were hyper-reflexic bilaterally in his lower ex-tremities, his plantar reflex was down-going bilaterally and clonus could notbe elicited. The patient’s rectal tonewas normal and perianal sensation wasintact, and his pinprick, light touch andvibration senses were intact in hislower extremities.

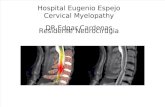

A plain and gadolinium-enhancedmagnetic resonance image of the patient’s whole spine showed in-tramedullary T2-weighted hyperintensityand cord expansion from thoracic spinalcord at the T8 level to the conusmedullaris with prominent peri-medullary flow voids surrounding thespinal cord that were consistent with engorged vessels (Figure 1). A contrast

DO

I:10

.150

3/cm

aj.0

7154

2

Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula: a treatable cause

of myelopathy

Teaching case report

Figure 1: Sagittal T2-weighted magneticresonance image of the thoracolumbarspine showing edema of the thoraciccord and conus medullaris (black arrows) and regional dilated peri-medullary vessels (white arrow) sugges-tive of a spinal vascular malformation.

Figure 2: Selective spinal angiogram of the right T10 segmental artery showing a fistu-lous connection (black arrow) between the segmental artery and the perimedullary venous plexus (white arrow).

Practice

magnetic resonance angiogram of thethoracic and lumbar spine showed afeeding vessel at the right thoracic T10level that was supplying an intraspinalvascular malformation. A catheter-basedspinal angiogram confirmed the pres-ence of a dorsal, dural arteriovenous fis-tula with extensive perimedullary venousreflux supplied from the right T10 seg-mental artery (Figure 2).

The patient was operated on within7 days of presentation because of pro-gressive myelopathy. A posterior tho-racic T9-T11 laminectomy and duro-tomy was performed, which showedengorged venous vessels on the surfaceof the spinal cord (Figure 3). An arteri-alized draining vein was identified aris-ing from the inner aspect of the duralsleeve of the right T10 nerve root. Thisvein was cauterized and divided, whichimmediately reduced the turgor of thedistended perimedullary venousplexus. Postoperatively, the patient regained full power in his legs with improvement in gait, and his pain wasmarkedly reduced. He had mild urinaryretention that was treated successfullywith bethanechol chloride.

This patient presented with a history ofwork-related radicular leg pain as wellas progressive weakness and signs andsymptoms of myelopathy. The differen-tial diagnosis for myelopathy is exten-sive; however, one starting point is thedifferentiation between structural andnonstructural lesions. Disorders thataffect the spinal cord can be classifiedas being from bony, intervertebral disk-related, tumorous, infectious, cystic or

hemorrhagic causes. A thorough his-tory should be obtained with emphasison pain and neurologic symptoms,past trauma and risk factors for cancerand infection. A neurologic examina-tion will help to determine whether apatient is affected by myelopathy (withupper motor neuron signs) or radicu-lopathy (with lower motor neuronsigns) (Table 1). Mixed upper and lowermotor neuron findings may be present.A neurologic examination will alsohelp to localize the lesion to the cervi-cal, thoracic or lumbar level. Oncemyelopathy is suspected, initial investi-gations should be guided by the pa-tient’s history and the results of a phys-ical examination. However, urgentmagnetic resonance imaging of thespinal column is almost always neces-sary for patients with myelopathy. Incases with a spinal dural ateriovenousfistula, the radiologic findings include

regional T2-weighted hyperintensity ofthe spinal cord and local dilated peri-medullary vessels.1 Neurosurgical refer-ral is appropriate if a structural lesion isidentified.

The exact incidence of spinal duralateriovenous fistula is unclear; how-ever, our tertiary care centre, whichserves a population of 1.4 million, hasabout 1–3 cases each year. Spinal duralateriovenous fistulas are 5 times morecommon among men compared withwomen, with a mean age at diagnosisof 55–60 years, and the most frequentlocation is the thoracolumbar spine.This condition arises from an acquiredabnormal communication between abranch of a segmental spinal artery anda radicular vein connecting with theperimedullary venous plexus of thespinal cord. High venous pressure inthe arterialized vessels is thought toproduce edema and relative ischemia ofthe spinal cord, which results in myelo-pathic symptoms.

Symptoms of spinal dural aterio-venous fistula may be mistaken for morecommon spinal degenerative conditionssuch as lumbar spondylosis and neuro-genic claudication, multiple sclerosis,spinal cord tumour, transverse myelitisand polyneuropathy. Delayed diagnosisis common, with the time from symp-tom onset to diagnosis ranging from 12to 36 months.1 Progressive weakness,muscle spasm, fecal incontinence, over-flow urinary incontinence or urinary retention and erectile dysfunction arecharacteristic of myelopathy, but they

Table 1: Symptoms and signs of myelopathy and radiculopathy

Symptoms or signs Myelopathy Radiculopathy

Symptoms • Weakness of limbs, typically proximal and bilateral

• Muscle spasm

• Fecal incontinence

• Erectile dysfunction

• Urinary retention or incontinence

• Weakness in muscles supplied by affected nerve roots

• Dermatomal paresthesias

• Pain along dermatome

Signs • Increased muscle tone

• Hyper-reflexia

• Upgoing plantar reflex

• Clonus

• Decreased muscle tone

• Hypo-reflexia

• Downgoing plantar reflex

• No clonus

Figure 3: Intraoperative photograph of a spinal dural arteriovenous fistula (black ar-row) and engorged perimedullary vessels (white arrow).

Cou

rtes

y of

Dr.

R.J.

Hur

lber

t

CMAJ • May 6, 2008 • 178(10) 11228877

Practice

CMAJ • May 6, 2008 • 178(10)11228888

are not specific to spinal dural aterio-venous fistula. These symptoms may beaggravated by activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure. In about one-third of cases, lower motor neuron find-ings precede upper motor neuron find-ings.1 Sensory findings may follow anascending radicular pattern (Table 1).

Spinal dural ateriovenous fistulahas a variable course ranging fromacute onset that mimics anterior spinalartery syndrome to chronic and pro-gressive symptoms.1 Untreated, it mayprogress to subacute necrosis of the

spinal cord with permanent and severeimpairment, including limb paralysisand loss of sphincter function (Foix–Alajouanine syndrome).

Treatment options include openspinal surgery to disconnect the arterial-ized draining vein or endovascular embolization; however, surgery has ahigher likelihood of cure. In contrast,the first choice treatment for otherspinal arteriovenous malformationstends to be embolization.2 Recovery depends on the age of the patient andthe severity of preoperative myelopathy.3

Most patients have improvement of theirsymptoms and a reversal of radiologicchanges after treatment.4 Gait difficultyand muscle strength respond best totreatment, and micturition, pain andmuscle spasms respond less well.1

Although it is a rare disease, clini-cians should be aware of spinal dural arteriovenous fistula as a frequently mis-diagnosed and progressively disablingneurologic condition that can be cured(Box 1). Early clinical identification cou-

pled with urgent imaging can shortenthe time to diagnosis and treatment.

Roberto Jose Diaz MDJohn H. Wong MD MSc

Division of NeurosurgeryDepartment of Clinical NeurosciencesFoothills Medical CentreUniversity of CalgaryCalgary, Alta.

REFERENCES:1. Jellema K, Tijssen CC, van Gijn J. Spinal dural arte-

riovenous fistulas: a congestive myelopathy thatinitially mimics a peripheral nerve disorder. Brain2006;129:3150-64.

2. Veznedaroglu E, Nelson PK, Jabbour PM, et al. En-dovascular treatment of spinal cord arteriovenousmalformations. Neurosurgery 2006;59:S202-9.

3. Nagata S, Morioka T, Natori Y, et al. Factors thataffect the surgical outcomes of spinal dural arteri-ovenous fistulas. Surg Neurol 2006;65:563-8.

4. Steinmetz MP, Chow MM, Krishnaney AA, et al. Out-come after the treatment of spinal dural arteriovenousfistulae: a contemporary single-institution series andmeta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2004;55:77-87.

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Box1: Clinical features of spinal dural atriovenous fistula

• A rare but treatable cause of myelopathy

• May present with a mix of myelopathic and radicular findings

• Mean age at diagnosis ranges from 55 to 60

• More common in males

Stay informed! Receive the latest Health Product Advisories and the Canadian Adverse Reaction Newsletter by email.

Soyez à jour! Recevez par courriel les derniers Avis sur les produits de santéet le Bulletin canadien des effets indésirables.

Subscribe to MedEffect e-Notice at www.healthcanada.gc.ca/medeffectAbonnez-vous à l’Avis électronique MedEffet à www.santecanada.gc.ca/medeffet

Practice

Clinical quiz

DO

I:10

.150

3/cm

aj.0

7009

4

Figure 1: A chest radiograph (left) of a 53-year-old man showing a mass (arrow) in the lower lobe of his right lung, and a computedtomography scan of his chest (right) revealing a 2.5 × 2.9-cm spiculated mass (arrow), pleural effusion on the right side, mediastinallymphadenopathy and postobstructive pneumonia.

Malaise, weight loss, pleuritic chest pain and productive cough: What is your call?

chest revealed a 2.5 × 2.9-cm spiculatedmass, pleural effusion on the right side,mediastinal lymphadenopathy and pos-tobstructive pneumonia (Figure 1). Theresults of extensive imaging tests formetastatic disease, including computedtomography scans of his head, ab-domen and pelvis and a bone scan,were negative.

What is the diagnosis?

a. Pulmonary tuberculosisb. Lung cancerc. Pulmonary actinomycosisd. Pulmonary nocardiosise. Pulmonary blastomycosis

A 53-year-old man from Texas pres-ented with a 2-month history ofmalaise, anorexia and 14-kg weightloss, and a 2-week history of chest painand a productive cough of yellow–brown sputum. He was a smoker(40 pack-year), and he had hyperten-sion, hepatitis C and a long history ofalcohol abuse (4–6 beers per day for> 25 years). He denied having fever,chills, night sweats, dyspnea or hemop-tysis. His vital signs were normal, andphysical examination revealed temporalwasting, pallor, poor oral hygiene withmultiple cavities, wheezing and de-creased breath sounds in the right lung,and clubbing of his fingers and toes. Hehad mild normocytic anemia and hypo-albuminemia. He was HIV negative. Achest radiograph showed a mass in thelower lobe of his right lung and a locu-lated effusion in the right pleura (Figure1). A computed tomography scan of his See page 1290 for diagnosis.

CMAJ • May 6, 2008 • 178(10)© 2008 Canadian Medical Association or its licensors

11228899

Practice

CMAJ • May 6, 2008 • 178(10)11229900

Discussion

Although the most likely diagnosis in asmoker who presents with the clinicaland radiographic manifestations wedescribed would be lung cancer, in ourpatient the answer is (c) pulmonary ac-tinomycosis. We performed a bronch-oscopy and an endoscopic ultrasoundbiopsy of paratracheal lymph nodes,but the results did not reveal the diag-nosis. We also performed medi-astinoscopy, video-assisted thoraco-scopic surgery and decortication of theright pleura. The results of all biopsieswere negative for malignant disease.The results of routine, fungal and acid-fast bacilli cultures were also negative.The pathological specimen from thepleura showed extensive neutrophilicinfiltration and sulfur granules (Figure2) as well as branching micro-organisms consistent with Actino-myces (Figure 3). The patient’s symp-toms resolved after a 6-month courseof amoxicillin. A subsequent radio-graph of his chest showed improve-ment (Figure 4). The patient remainedasymptomatic 2 years after the comple-tion of treatment and showed no evi-dence of relapse.

Pulmonary actinomycosis: Pulmonaryactinomycosis is rare.1 It accounts for10%–15% of reported cases of actino-mycosis and occurs less frequently thanthe cervicofacial and abdominopelvicforms of the disease.1,2 It is caused by

Actinomyces, a genus of gram-positiveanaerobic micro-organisms that aresusceptible to several classes of anti-biotics, including penicillin G (the anti-biotic of choice) and other β-lactams,clindamycin, tetracycline and macro-lides.1,2 Although Actinomyces israelii isby far the most common species foundin humans, Actinomyces meyeri is morefrequently seen in cases of pulmonaryactinomycosis.1,2 Important risk factorsfor pulmonary actinomycosis includepoor dental hygiene and alcohol abuse,both of which were present in our pa-tient. These risk factors predispose pa-tients to aspirate oral secretions con-taining Actinomyces bacteria into thelower respiratory tract.1,2

The clinical presentation and radio-graphic features of pulmonary actino-mycosis closely resemble those of lungcancer and chronic suppurative pul-monary infections such as tuberculosisand fungal infections.2 Therefore, thediagnosis of pulmonary actinomycosisis challenging and often delayed.Weese and Smith reported that the av-erage time from symptom onset to di-agnosis was 6 months, and the infec-tion was suspected at the time ofadmission in less than 10% of casesthat were later diagnosed as pulmonaryactinomycosis.3 Pulmonary actino-mycosis should be suspected in pa-tients with known risk factors (e.g., al-cohol abuse, poor dental hygiene) whopresent with nonspecific, subacute, orchronic constitutional and respiratorysymptoms. Clinical features that canpoint to a diagnosis of pulmonaryactinomycosis in such patients include

the development of draining sinustracts, and radiographic features in-clude the presence of pulmonary ab-normalities that progress across differ-ent anatomic planes.

For a definitive diagnosis of actino-mycosis, the presence of sulfur gran-ules in cultures or biopsy material is re-quired. In tissues, Actinomyces speciesgrow in filamentous clusters sur-rounded by polymorphonuclearneutrophils, as shown in Figure 2 andFigure 3. When these clusters exudefrom soft tissues through sinus tracts,they are macroscopically yellow, andare called sulfur granules. In rare cases,Actinomyces species can be identifiedin blood cultures.1 A prolonged course(6–12 months) of antibiotics is neces-sary to treat pulmonary actinomycosisand is usually successful if startedearly.2 Thus, pulmonary actinomycosisshould be suspected in patients whoinitially receive a diagnosis ofcommunity-acquired pneumonia andrespond to antimicrobial therapy butwho promptly relapse after completionof a short course of antibiotics.

Differential diagnosis: As mentionedpreviously, the clinical and radio-graphic presentation of chronic lunginfections and lung cancer may be sim-ilar to that of pulmonary actinomycosis(Table 1).1,2 We ruled out lung cancer inour patient because the results of mul-tiple tissue biopsies obtained duringbronchoscopy and decortication of thepleura were negative.

Reactivation of pulmonary tubercu-losis typically affects the upper lobes of

Clinical quiz

Figure 2: Histological section of thespecimen from the right pleura show-ing extensive neutrophilic infiltrationand sulfur granules (arrow and inset).Hematoxylin and eosin stain, originalmagnification × 100.

Figure 3: Histological sections of pleural specimen showing branching micro-organisms consistent with Actinomyces. Left: Gomori methenamine silver stain, ori-ginal magnification × 400. Right: Gram stain, original magnification × 1000.

Practice

CMAJ • May 6, 2008 • 178(10) 11229911

the lungs. This was not the case in theradiographs of our patient, whose acid-fast bacilli cultures were also negative.

Pulmonary nocardiosis usually af-fects immunocompromised patients.It is caused by Nocardia species —gram-positive branching filamentousrods that resemble Actinomycesspecies. Unlike Actinomyces species,the presence of Nocardia species is de-tected with the modified acid-fastKinyoun stain.4

Finally, pulmonary blastomycosis isan endemic mycosis that can also mas-querade as lung cancer.5 However, theabsence of a relevant travel history, theabsence of blastomycosis in Texas andthe negative fungal cultures in our pa-tient made this diagnosis unlikely.

Michail S. Lionakis MD ScDRichard J. Hamill MDSection of Infectious DiseasesMichael E. DeBakey Veterans AffairsMedical Center

Baylor College of MedicineHouston, Tex.

REFERENCES1. Smego RA Jr, Foglia G. Actinomycosis. Clin Infect

Dis 1998;26:1255-61.2. Mabeza GF, Macfarlane J. Pulmonary actinomyco-

sis. Eur Respir J 2003;21:545-51.3. Weese WC, Smith IM. A study of 57 cases of actin-

omycosis over a 36-year period. A diagnostic ‘fail-ure’ with good prognosis after treatment. Arch In-tern Med 1975;135:1562-8.

4. Heffner JE. Pleuropulmonary manifestations of

actinomycosis and nocardiosis. Semin Respir In-fect 1988;3:352-61.

5. Poe RH, Vassallo CL, Plessinger VA, et al. Pul-monary blastomycosis versus carcinoma — a chal-lenging differential. Am J Med Sci 1972;263:145-55.

CMAJ invites contributions to theClinical Quiz, which uses multiple-choice questions to guide a focusedimage-based discussion of thediagnosis or management of clinicalcases. Submit manuscripts online athttp://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cmaj.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

Figure 4: Radiograph of the patient’schest showing improvement after a 6-month course of amoxicillin.

Table 1: Differential diagnosis of pulmonary actinomycosis

Condition Characteristics

Pulmonary tuberculosis

Reactivation of pulmonary tuberculosis usually involves the apical-posterior segments of the upper lobes of the lungs. Primary tuberculosis usually involves the middle lobe of the right lung and the lower lobes of both lungs. About two-thirds of patients with primary or reactivated tuberculosis have hilar lymphadenopathy.

Lung cancer Patients who are older than 50, have a history of smoking tobacco or were exposed to asbestos have a higher clinical risk of lung cancer. Radiographic features of a lung mass that raise suspicion of lung cancer include a size of > 1 cm in diameter, rapid growth in sequential radiographs, irregular or spiculated margins, associated lymphadenopathy or pleural effusion, additional lung masses and eccentric asymmetric calcification.

Pulmonary actinomycosis

Characterized by contiguous anatomic spread, pulmonary actinomycosis may involve the pleura or the chest wall, with sinus tract formation and discharge of sulfur granules. The infection is typically seen in patients who are prone to aspiration of oral secretions because of poor oral hygiene and alcohol abuse.

Pulmonary nocardiosis

Caused by Nocardia species (gram-positive filamentous bacteria that are found worldwide in soil), pulmonary nocardiosis is typically seen in immunocompromised patients with hematologic malignant disease. Abscesses in distant sites, such as the central nervous system, may occur.

Pulmonary blastomycosis

Risks include travel to disease-endemic areas, including parts of the United States (states bordering the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers and the Midwest), Canada (Ontario and Manitoba, particularly around Kenora, Ontario) and Africa (South Africa and Zimbabwe).

For prescribing information see page 1346