New Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 Diseases... · 2007. 1. 8. · Cancer...

Transcript of New Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 Diseases... · 2007. 1. 8. · Cancer...

AL

AZAR

CA CO

CT

DE

FL

GA

ID

IL IN

IA

KS

KY

LA

ME

MD

MA

MN

MS

MO

MT

NENV

NH

NJ

NM

NY

NC

ND

OH

OK

OR

PA

RI

SC

SD

TN

TX

UT

VT

VA

WA

WV

WIWY

DC

HI

AK

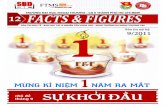

Tobacco Excise Tax by State, 2004*

Equal to or above the national average of 79 cents per pack

Below the national average in the range of 35 to 78 cents per pack

Far below the national average up to 34 cents per pack*Data current as of October 2004.

Source: National Government Relations Department, American Cancer Society, 2004

MI

Cancer Prevention& Early Detection

Facts & Figures 2005

ContentsPreface 1

Children and Adolescents 3

Youth Tobacco Use 3

Overweight and Obesity, Physical Inactivity, and Nutrition Among Youth 8

Sun Protection 15

Adult Cancer Prevention 17

Adult Tobacco Use 17

Overweight and Obesity, Physical Inactivity, and Nutrition Among Adults 25

American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention 26

Cancer Screening 35

Breast Cancer Screening 35

Screening Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer in Asymptomatic People 36

Cervical Cancer Screening 37

Colon and Rectum Cancer Screening 39

Prostate Cancer Screening 44

Barriers and Opportunities to Improve Cancer Screening 44

Statistical Notes 47

Survey Sources 49

References 50

List of Tables and Figures 56

Acknowledgments 57

©2005, American Cancer Society, Inc. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce thispublication or portions thereof in any form. For written permission, address the American CancerSociety, 1599 Clifton Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30329-4251.

This publication attempts to summarize current scientific information about cancer. Except whenspecified, it does not represent the official policy of the American Cancer Society.

Suggested citation: American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts &Figures 2005. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2005.

For more information, contact:Vilma Cokkinides, PhD, MSPHJessica Albano, MPHAlicia Samuels, MPHElizabeth M.Ward, PhDMichael J. Thun, MD, MS

Department of Epidemiology and Surveillance Research

Preface

Tobacco use, physical inactivity, obesity, and poor nutri-tion are major preventable causes of cancer and otherdiseases in the US. The American Cancer Society esti-mates that in 2005, more than 168,140 cancer deaths willbe caused by tobacco use alone. In addition, scientistsestimate that approximately one-third (190,090) of the570,280 cancer deaths expected to occur in 2005 will berelated to poor nutrition, physical inactivity, overweight,obesity, and other lifestyle factors.1-3 Many deaths fromcancers of the breast, colon, rectum, and uterine cervixcould also be prevented by greater utilization of estab-lished screening tests. While these categories overlapand cannot simply be added to determine the total num-ber of fatal cancers that could be prevented, a conserva-tive estimate is that at least half of all cancer deathscould in principle be avoided by the application of exist-ing knowledge.

To support cancer control efforts, the American CancerSociety has published Cancer Prevention & EarlyDetection Facts and Figures (CPED) annually since 1992.CPED is intended to be a resource for American CancerSociety staff, volunteers, and others working tostrengthen cancer prevention and early detection effortsat the local, state, and/or national levels. CPED comple-ments the companion publication, Cancer Facts &Figures, by providing current information on the preva-lence of modifiable risk factors for cancer and the uti-lization of screening tests that can detect cancer early,when treatment is most effective. It includes informa-tion on the burden of disease, death, and economic costsattributable to factors such as tobacco use, obesity, phys-ical inactivity, and under-usage of established screeningtests. It identifies social, legislative, and economic fac-tors that influence individual behaviors that affectcancer risk. It describes best practices for reducingtobacco usage by adults and children and highlightssuccess stories in community efforts to reduce tobaccodependence, increase physical activity, and improvedietary patterns. Although the report is divided into sep-arate sections that discuss cancer prevention in childrenand adolescents and prevention and early detection inadults, these topics are interrelated; many of the strate-gies that foster positive behaviors at one age continue tohave a beneficial effect on health throughout life.

Issues relating to cancer prevention and early detectionare central to the American Cancer Society’s mission andits 2015 goals. The Society is dedicated to eliminating

cancer as a major public health problem by preventingcancer, saving lives, and diminishing suffering fromcancer, through research, education, advocacy, andservice.

In 1999, the Society set bold challenge goals for thenation that, if met, would significantly lower cancerincidence and mortality rates and improve the quality oflife for all cancer survivors by 2015. The AmericanCancer Society has also developed nationwide objectivesthat set the framework for achieving the 2015 goals (seesidebar, page 2). These objectives can be achieved byimproved collaboration among government agencies,private companies, nonprofit organizations, health careproviders, policymakers, insurers, and the Americanpublic.

One example of collaboration is a groundbreaking part-nership of the American Cancer Society, the AmericanDiabetes Association, and the American HeartAssociation, called Everyday Choices for a HealthierLifeTM. This initiative, launched in June 2004, combinesthe efforts of the three organizations to address com-mon risk factors, such as tobacco use, obesity, physicalinactivity, poor nutrition, and under-utilization of effec-tive screening tests. Collectively, cancer, cardiovasculardisease, and diabetes account for approximately two-thirds of all deaths in the United States and about $700billion in direct and indirect economic costs each year.4

By working together, the three organizations can moreeffectively address common goals such as preventing theinitiation of tobacco use, facilitating cessation, promot-ing proper nutrition and weight control, improvingnutrition, increasing physical activity, and establishingroutine use of effective screening tests. The collabora-tion also seeks to increase the focus on preventionamong health care providers, and to support legislationthat increases funding for and access to prevention pro-grams and support for research. More information aboutthis initiative can be found at www.everydaychoices.org.

There is increasing recognition of the impact of commu-nity and environmental factors on individual healthbehaviors.5,6 Physical activity, good nutrition, and cancerscreening can all be influenced through legislation,public health policies, and adequate funding for pro-grams, similar to comprehensive tobacco control.7

Public policy and legislation at the federal, state, andlocal levels can increase access to preventive health serv-ices, including cancer screening.8 For example, at thefederal level, the American Cancer Society has advocatedfor increased funding of the Centers for Disease Control

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 1

and Prevention’s National Breast and Cervical CancerEarly Detection Program (NBCCEDP) to help low-income and uninsured women obtain screening. At boththe federal and state levels, the American Cancer Societyhas advocated for laws requiring insurers to provide cov-erage for recommended cancer screening in health careplans, such as coverage for the full range of colorectal

cancer screening tests. In addition, the Society hasworked at both the state and federal levels to ensureMedicaid coverage for the treatment of breast and cervi-cal cancer cases diagnosed through the NBCCEDP.8

These and other community, policy, and legislative ini-tiatives are highlighted in this publication.

2 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

American Cancer Society Goals and Objectives

2015 Challenge Goals• A 50% reduction in age-adjusted cancer mortality rates

• A 25% reduction in age-adjusted cancer incidence rates

• A measurable improvement in the quality of life (physi-cal, psychological, social, and spiritual), from the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life, of all cancersurvivors

2015 Nationwide ObjectivesAdult Tobacco Use: Reduce to 12% the proportion ofadults (18 and older) who use tobacco products.

Youth Tobacco Use: Reduce to 10% the proportion ofyoung people (under 18) who use tobacco products.

Nutrition: Increase to 75% the proportion of persons whofollow American Cancer Society guidelines with respect toconsumption of fruits and vegetables as published in theAmerican Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition andPhysical Activity for Cancer Prevention.

Physical Activity: Increase to 90% the proportion of youth(high school students) and to 60% the proportion of adultswho follow American Cancer Society guidelines withrespect to the appropriate level of physical activity aspublished in the American Cancer Society Guidelines onNutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention.

Comprehensive School Health Education: Increase to50% the proportion of school districts that provide acomprehensive or coordinated school health educationprogram.

Sun Protection: Increase to 75% the proportion of peopleof all ages who use at least two or more of the followingprotective measures which may reduce the risk of skincancer: avoid the sun between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.; wearsun-protective clothing when exposed to sunlight; usesunscreen with an SPF 15 or higher; and avoid artificialsources of ultraviolet light (e.g., sun lamps, tanningbooths).

Breast Cancer Early Detection: Increase to 90% theproportion of women aged 40 and older who have breastscreening consistent with American Cancer Society guide-lines (by 2008).

Colorectal Cancer Early Detection: Increase to 75% theproportion of people aged 50 and older who have colorectalscreening consistent with American Cancer Societyguidelines.

Prostate Cancer Early Detection: Increase to 90% theproportion of men aged 50 and older who follow AmericanCancer Society detection guidelines for prostate cancer.

The health of young people, and the adults they willbecome, is critically linked to the establishment ofhealthy behaviors in childhood.9 Risk factors such astobacco addiction, unhealthy dietary patterns, and phys-ical inactivity during childhood and adolescence canresult in life-threatening cancers, cardiovascular disease,and other major illnesses later in life.9 Children whoadopt healthy habits at an early age are more likely tocontinue these behaviors throughout life. It is far easierto establish healthy practices initially than to changebehaviors later. For example:

• About half of youngsters who are overweight as chil-dren will remain overweight in adulthood,10 and 70%of those who are overweight by adolescence willremain overweight as adults.6

• Physically active children are more likely to grow up tobe physically active adults, whereas inactive childrenand youth are much more inclined to be sedentaryadults.11

• Almost 90% of current adult smokers became addictedto tobacco at or before age 18.12

Childhood is not only a formative period; it also presentsan opportunity to teach children healthy lifestyle habitsin school. There are more than 50 million students cur-rently enrolled in the nation’s public and private elemen-tary and high schools (grades K-12). The 129,000 schoolsin the US provide an organizational structure throughwhich health information and prevention programs canbe delivered.9

Furthermore, children are greatly influenced by theirsocial environment, which in turn is strongly influencedby public policies. For instance, adolescents are morelikely to initiate smoking if their film idols smoke in themovies, their favorite sport is sponsored by a tobaccocompany, they see people smoking around them, andtobacco products are cheap and readily available.12

Similarly, children are more likely to engage in sports andother forms of physical activity if safe and enjoyable par-ticipation in these activities is encouraged at school, inafter-school care programs, and in their communities.13

Children who can walk or bike to school safely are morelikely to do so.13 Community support, public health pol-icy, and legislation offer multiple opportunities toimprove the health behavior of future generations.

Youth Tobacco UseAlmost everyone who uses tobacco in the US began as anadolescent. In 2003, 21.9% of US high school studentsreported smoking at least one day in the last 30 days,with 9.7% reporting frequent smoking or smoking for 20or more of the last 30 days (Table 1A).14 According to theMonitoring the Future survey, cigarette smoking variesby race/ethnicity among US 12th graders, with the high-est prevalence among non-Hispanic whites, intermedi-ate prevalence among Hispanics/Latinos, and the lowestprevalence among African Americans (Figure 1A).

Trends Over TimeThe prevalence of current cigarette smoking hasdecreased among white, African American, andHispanic/Latino high school students from 1997 to 2003(Figure 1B).15 The decrease has occurred despite a majorincrease in tobacco company expenditures for promo-tion of cigarettes. Promotions specifically target youngpeople by sponsoring sporting events and by giving or

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 3

Figure 1A. Current* Cigarette Smoking Among 12th Graders, by Race/Ethnicity, 1977-2003

Perc

ent

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

*Used cigarettes in the last 30 days.

Source: Monitoring the Future Survey, 1975-2003, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

12th grade, non-Hispanic white

12th grade, African American

12th grade, Hispanic/Latino

Year

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

200319971992198719821977

Children and Adolescents

4 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

Table 1A. Tobacco Use, High School Students, by State and City, 2003% Current % Frequent % Current % Current smokeless

cigarette smoking* Rank† cigarette smoking‡ cigar use§ tobacco use ||

United States 21.9 9.7 14.8 8.7

State (out of 32 states)Alabama 24.7 21 12.6 13.0 10.5Alaska 19.2 5 8.0 7.8 11.2Arizona 20.9 10 7.3 14.2 4.8Delaware 23.5 17 12.1 12.2 3.4Florida 18.1 3 7.5 13.4 4.8Georgia 20.9 11 8.7 13.9 7.6

Idaho 14.0 2 6.1 8.7 5.7Indiana 25.6 25 12.4 14.7 7.2Kentucky 32.7 32 18.4 18.7 13.7Maine 20.5 9 10.1 11.1 4.3Massachusetts 20.9 12 9.5 11.8 4.1

Michigan 22.6 15 11.3 13.6 6.5Mississippi 25.0 24 12.0 18.4 8.2Missouri 24.8 22 13.6 13.3 5.7Montana 22.9 16 10.8 14.1 13.2Nebraska 24.1 19 11.2 18.2 10.1

Nevada 19.6 7 8.8 N/A 3.6New Hampshire 19.1 4 9.6 13.5 4.3New York 20.2 8 9.2 8.5 4.2North Carolina 24.8 23 12.4 N/A N/ANorth Dakota 30.2 31 16.0 13.0 10.3

Ohio 22.2 14 11.0 13.6 8.0Oklahoma 26.5 27 12.8 17.4 12.7Rhode Island 19.3 6 9.0 10.5 4.6South Dakota 30.0 30 14.7 13.8 15.3Tennessee 27.6 28 14.7 16.6 12.1

Texas¶ 24.3 20 7.9 14.6 6.8Utah 7.3 1 3.0 7.3 3.1Vermont 22.1 13 10.9 11.9 5.2West Virginia 28.5 29 17.7 13.3 13.6Wisconsin 23.6 18 11.6 N/A 7.9Wyoming 26.0 26 13.3 14.7 13.3

City (out of 18 cities)Boston, MA 13.1 6 3.8 8.8 2.2Chicago, IL 16.9 16 5.6 15.6 3.5Dallas, TX 18.1 18 4.0 17.0 2.7Dekalb County, GA 9.5 3 2.5 8.8 2.3Detroit, MI 9.1 1 1.7 7.2 3.2District of Columbia 13.2 7 3.8 11.2 5.0

Ft. Lauderdale, FL 13.4 9 5.3 10.6 3.7Los Angeles, CA 14.4 13 2.4 10.7 2.8Memphis, TN 9.2 2 2.3 13.1 1.5Miami, FL 13.5 10 4.6 10.2 2.4Milwaukee, WI 13.6 11 6.3 N/A 5.5New Orleans, LA 11.5 4 4.1 8.9 3.6

New York City, NY 14.8 14 5.3 5.5 1.6Orange County, FL 16.0 15 5.2 11.1 2.4Palm Beach, FL 17.0 17 8.2 14.2 3.5Philadelphia, PA 13.9 12 5.9 5.2 2.4San Bernardino, CA 12.4 5 3.1 10.4 3.7San Diego, CA 13.2 8 3.4 12.0 2.5

*Smoked cigarettes on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey. †Rank is based on % current cigarette smoking. ‡Smoked cigarettes on 20 ormore of the 30 days preceding the survey. §Smoked cigars, cigarillos, or little cigars on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey. ||Used chewingtobacco or snuff on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey. ¶Survey did not include students from one of the state's largest school districts. N/A = Data not available. Note: Data are not available for all states since participation in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System is a voluntarycollaboration between a state's departments of health and education.

Source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, 2003, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Controland Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(SS-2).

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

exchanging for empty cigarette packs T-shirts, caps,sunglasses, key chains, and sporting goods bearing acigarette brand’s logo.16 In 2002, advertising and promo-tional expenditures topped $12 billion, nearly double theamount spent in 1997.17

The decreases in smoking among high school studentscan be attributed, at least in part, to rising cigaretteprices, restrictions on public smoking, and counter-advertising.18-20 In 2002 alone, 21 states – more statesthan in the previous 5 years combined – raised theircigarette taxes.19

Patterns of Smoking Initiation in YouthMany young people begin to experiment with cigarettesat very young ages. About 36% of middle or junior highschool students21 and 58% of high school students14 havetried cigarette smoking. Figure 1C shows that the pro-gression to established (current) smoking among adoles-cents is strongly associated with age. Experimentationappears to peak at age 13-14 while the proportion ofadolescents who are established smokers rises steadilyfrom age 11-18.22 The addictive and toxic properties oftobacco smoke may be even worse for adolescents,whose lungs are still developing, than for adults.

Recent research documents the highly addictive natureof cigarettes among adolescents.23 Progression to nico-tine dependence, once thought to develop over severalyears, has been shown to develop soon after initiationand to lead to smoking intensification. One studyshowed that approximately 20% of adolescents reported

nicotine dependence symptoms within 1 month ofinitiating regular smoking, with a median consumptionlevel at the onset of symptoms of only 2 cigarettes on 1day per week.24 Even adolescents who had smoked onlya couple of times reported some symptoms of nicotinedependence which increased in frequency with morefrequent smoking.25 These findings should be high-lighted in educating young people about the dangers ofexperimenting with tobacco.

Studies show that being exposed to tobacco industrypromotions increases the likelihood that adolescentswill experiment with cigarettes and transition fromexperimentation to regular smoking.22,26 One studyshowed that young people who were exposed to tobaccomarketing (owned a promotional item displaying atobacco logo or were able to name a brand whose adver-tisements attracted their attention) were more likely toinitiate smoking and more than twice as likely tobecome established smokers.26

Comprehensive Approach to Youth TobaccoControlAlthough recent trends in youth smoking have beenfavorable, US prevalence remains high.14 In the absenceof intervention, most adolescent smokers continuesmoking as adults.12 Studies have shown that compre-hensive tobacco control programs, including increasesin excise taxes, reduce the rates of adolescent smoking.5

States that have imposed higher excise taxes, thus rais-ing the price of cigarettes, generally have lower youth

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 5

Figure 1B. Current* Cigarette Smoking Among High School Students, by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, 1991-2003Pe

rcen

t

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

*Smoked cigarettes on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey.

Source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(23):499-502.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

1991 1995 1997

40 3940

32 31 30

37

32

26

38

33

11 12

17 18

13 14

28 28

22

16

23

33 32

28

35 3634

27

Hispanic/Latino male

Hispanic/Latina female

African American (non-Hispanic)

female

African American (non-Hispanic)

male

White (non-Hispanic)female

White (non-Hispanic)male

40

30

35

27

32

23

1411

1619

27

18 19

1993 2001 20031999

smoking prevalence. In addition to supporting increasedexcise taxes, advocacy for smoke-free school environ-ments and restrictions on youth access to tobaccoproducts are important factors in decreasing smokinginitiation and encouraging youth to quit smoking.5

School-based smoking prevention programs can beeffective as part of comprehensive tobacco control pro-grams.5 Because of the early age of cigarette initiation,smoking prevention classes must be taught from ele-mentary school to high school.5 The Surgeon Generalrecommends that tobacco use prevention begin at orbefore sixth grade. Currently, however, 25% of states donot require that tobacco use prevention be taught in ele-mentary schools.27 Because the long-term consequencesof smoking may seem remote to adolescent smokers,smoking prevention materials geared to youth shouldfocus on both short- and long-term consequences ofsmoking, such as lower sports performance, breath odor,being manipulated and exploited by the tobacco compa-nies, and reduced physical attractiveness due to stainingof teeth and fingers.23,28

Evidence suggests that antismoking media campaignsare effective in reducing smoking initiation in earlyadolescence.29 Children aged 12-13 years who reportexposure to effective counter-advertising on televisionare significantly less likely to progress to establishedsmoking over a 4-year period, with no effect observed

among older adolescents (14 to 15 years).29 States thathave utilized extensive paid media campaigns in com-bination with other anti-tobacco activities have seenrapid declines in youth smoking prevalence.30 In devel-oping its “Truth” campaign, the Florida Governor’sOffice worked with teen advisors to develop a mediacampaign that countered the image perception ofsmoking as cool and rebellious. Significant declines insmoking prevalence were reported among middle andhigh school students following implementation of theprogram,5 with a 40% reduction over 2 years among mid-dle school students.30

The state of Massachusetts initiated a multi-facetedyouth tobacco control program that included commu-nity-based efforts, statewide media campaigns, andschool-based tobacco education. The implementation ofthese efforts was associated with a decline in youthsmoking prevalence from 36% in 1995 to 30% in 1999.31

The television component of Massachusetts’ media cam-paign has been identified as an essential element inslowing the rate of progression to established smokingamong young adolescents.29

Recently, several of the most effective comprehensivetobacco control programs in the nation have beenjeopardized by severe budget cuts. The tobacco controlbudget in Massachusetts was cut from $48 million in2002 to $2.5 million in 2004; in Florida, the budget was

6 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

Figure 1C. Progression to Established Smoking of US Youth by Age, 1999-2000Pe

rcen

t

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

*Students who have never smoked but are open to smoking and students who have tried a cigarette but have smoked fewer than 26 cigarettes in their lifetime. †Students who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes and smoked on 1 or more days in the 30 days preceding the survey. ‡Students who have smoked 100 cigarettes or more but have not smoked in the past 30 days.

Source: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 1999-2000. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mowery et al. Progression to established smoking among US youths. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):331-337.

Experimenter* Current† Former‡

44.0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1817161514131211Age

26.9

39.3

48.7 50.2

45.6

41.038.0

13.8

1.61.22.5 2.9 3.7

18.8

22.9

28.2

7.8

3.30.40.9 0.20.4 0.0

cut from $37.5 million in 2003 to $1 million in 2004.32

After operating for 3 years, Minnesota’s Target Marketyouth anti-tobacco campaign ended in 2003, whenfunding was cut by more than 75%.33 Adolescents aged12-17 years were surveyed several times throughout thecampaign to ascertain their susceptibility to smoking(i.e., the percentage of youth who agree with the state-ment, “You will smoke a cigarette in the next year”). Sixmonths after the campaign was stopped, susceptibilityto smoking among adolescents had significantlyincreased from 43% to 53%.33

Cessation support is important for adolescents who arealready addicted to tobacco.34 In 2000, nearly 60% ofadolescent smokers made an unsuccessful attempt toquit in the previous year.21 School-based cessationprograms are an effective way to reach the majority ofadolescent smokers and equip them with the motivationand skills to quit.35

In order to increase the likelihood of successful cessa-tion, a full range of options, including pharmacotherapy,should be considered in treating nicotine dependence inadolescents.25 Although research on smoking-cessationinterventions for adolescents has been extremely lim-ited,36 a recent study showed that treatment with anicotine replacement patch appears effective in helpingadolescents quit.37

Parental guidance is important to maintain smoke-freehouseholds, set early nonsmoking expectations, monitoradolescents for signs of smoking, limit exposure to adultmedia, and counteract the influence of smokingdepicted in movies and other media as glamorous orgrown up.38 Prevention and cessation programs shouldaddress other tobacco products in addition tocigarettes.39

Other Tobacco ProductsWhile cigarettes remain the primary tobacco productused by youth, smokeless tobacco and cigars have gainedpopularity. Cigars are the second most popular type of

tobacco in all states, except South Dakota and Alaska,where smokeless tobacco is second to cigarettes.14

Tobacco usage varies by race and gender. Non-Hispanicwhite and Hispanic/Latino students smoke predomi-nantly cigarettes, while non-Hispanic AfricanAmericans are equally likely to smoke cigarettes andcigars. Male and female students were equally likely tosmoke cigarettes, but males were 5 times more likely touse smokeless tobacco and 2 times more likely to smokecigars than females. Table 1A provides data on currentand frequent cigarette smoking, current cigar use, andsmokeless tobacco use among high school students instates and cities for which these data are available for2003. A total of 27.5% of high school students reporteduse of any tobacco product in 2003.14 Other reports showthat among middle school students surveyed in 2002,13.3% reported current use of any tobacco product.Cigarette use was most commonly reported (10.1%),followed by cigars (6.0%), smokeless tobacco (3.7%), andpipes (3.5%).40

Alternative tobacco products such as bidis (small browncigarettes from India made of tobacco wrapped in a leafand tied with a thread) and kreteks (flavored cigarettescontaining tobacco and clove extract) are used less com-monly.40 Less than 5% of middle (2.4%) and high (2.6%)school students used bidis on one or more of the 30 dayspreceding the survey.40 Similarly, less than 5% of middle(2.0%) and high (2.7%) school students used kreteks onone or more of the 30 days preceding the survey.40 Allforms of tobacco are addictive and cause cancer andother life-threatening diseases. Moreover, use of othertobacco products among youth smokers may hasten theonset of nicotine dependence.41

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 7

Youth-oriented counter-advertising is effective athelping decrease smoking prevalence among highschool students by changing perceptions about thesocial acceptability of cigarette use.

Overweight and Obesity, PhysicalInactivity, and Nutrition Among Youth

Overweight and ObesityThe proportion of children aged 6-19 who are overweighthas tripled over the past 3 decades (Figure 1D). Thepotential consequences to the health of the populationare enormous. Some of the adverse health conditionsseen in overweight and obese adults, such as type IIdiabetes and high cholesterol levels, are now alsoappearing in overweight and obese adolescents.44 Inaddition, because overweight children tend to becomeoverweight adults,6,10 the current increase in childhoodoverweight and obesity will result in future adult popu-lations with increased risk of developing cancer, heartdisease, type II diabetes, and other serious chronicdiseases.45,46

The dramatic increase in the percentage of overweightchildren and adolescents has occurred among boys andgirls of all age groups and races/ethnicities, althoughMexican Americans and African Americans experiencedthe greatest increase.47 Table 1B shows the percentagesof youth who are either at risk for overweight or who areoverweight in states and major cities in the US.

Obesity occurs when caloric intake exceeds caloricexpenditures (for metabolism and physical activity) overtime. Even a small excess in caloric intake consumed

over time may upset this delicate balance.48 Physicalactivity, by itself, cannot offset large excesses in caloricintake. For example, 45 minutes of moderate physicalactivity are needed to burn off the calories in a 20-ouncesoda.49 The largest sugar-containing soft drink servingand its free refill in some fast-food chains provide half ofan adult’s daily caloric (but not nutritional) needs.49

There is broad consensus among medical and publichealth experts that countering the obesity epidemicamong children and adolescents ought to be a nationalhealth priority. A Surgeon General’s report in 2001, andmore recently a report by the Institute of Medicine(IOM), have emphasized the need to develop a compre-hensive approach to address the problem.6,50 The IOMreport, Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in theBalance, calls for coordinated efforts across schools,communities, industry, and governmental and non-governmental agencies to prevent and reduce obesity inAmerican youth.50

A combination of increasing physical activity and reduc-ing excess calorie consumption is needed to preventobesity in children. In 2003 the American Academy ofPediatrics released specific recommendations for theprevention of obesity in children.44 These include:

• Limiting television and video time to a maximum of 2hours per day

8 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

Figure 1D. Overweight* Children and Adolescents, by Age Group, 1971-2002

Perc

ent

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

*Body mass index at or above the 95th percentile of growth chart for age and sex.

Source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1971-1974, 1976-1980, 1988-1994, 1999-2000, 2001-2002, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hedley et al. Prevalenceof overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2847-2850.

1971-1974

1976-1980

1988-1994

1999-2002

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

12-19 years6-11 years2-5 yearsAge group

5.0 5.0

7.2

4.0

10.3

6.5

11.3

15.8

5.06.1

10.5

16.1

Success StoryHealthy Hawaii Initiative:Investing in PreventionHealthy Hawaii Initiative (HHI) is a school health programcreated in 1999 through funds from the MasterSettlement Agreement (MSA*) to promote health andreduce chronic disease among students and faculty. In itsfirst 3 years, the program provided professional develop-ment and teaching resources to health educators in avariety of settings, facilitated conferences to addressstatewide school health, and piloted and implementedcoordinated school health programs.42 In addition to theHHI, 25% of MSA funds were allocated for tobaccoeducation, prevention, and cessation programs.

*The 1998 settlement of a lawsuit launched by 46 stateAttorney Generals against large tobacco companies fortheir deceptive practices and to recover Medicaidexpenses due to smoking-induced illnesses43

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 9

Table 1B. Overweight and Related Factors, High School Students, by State and City, 2003% Watched % % % Eating

% three or % % Attended Played five or more At risk for more hours Moderate Vigorous physical on one or fruits andbecoming % per day of physical physical education more sports vegetables

overweight* Overweight† Rank‡ television§ activity|| activity¶ classes daily teams# a day**

United States 15.4 13.5 38.2 24.7 62.6 28.4 57.6 22.0

State out of 31 statesAlabama 14.5 13.5 24 41.7 18.6 58.0 33.3 56.3 14.5Alaska 14.4 11.0 14 27.5 28.2 67.8 18.2 62.8 16.1Arizona 13.6 10.8 12 36.6 29.2 66.9 23.2 51.7 20.4Delaware 16.7 13.5 25 45.4 22.6 57.2 28.7 53.4 19.5Florida 14.0 12.4 19 42.7 22.3 60.8 27.3 51.2 20.7Georgia 15.1 11.1 15 42.4 25.4 59.0 29.1 53.1 16.8Idaho 11.3 7.4 3 23.7 29.5 66.4 29.5 58.5 19.0Indiana 14.2 11.5 17 32.9 26.5 62.3 23.7 57.1 20.3

Kentucky 15.3 14.6 29 30.8 21.3 56.1 23.8 50.9 13.2Maine 14.6 12.8 22 26.3 24.6 60.6 8.2 56.7 22.6Massachusetts 13.8 9.9 8 31.3 23.5 61.3 13.7 53.7 N/AMichigan 15.0 12.4 20 34.8 25.6 62.3 27.5 N/A 18.4Mississippi 15.7 15.7 31 54.1 18.0 53.3 23.4 54.0 20.4Missouri 14.9 12.1 18 32.4 28.1 66.6 33.2 51.8 15.0Montana 11.6 8.1 4 25.3 23.9 62.3 32.6 60.5 16.7Nebraska 14.7 10.4 10 28.0 26.7 64.7 36.4 62.0 16.3

Nevada N/A N/A N/A N/A 27.2 66.6 N/A N/A N/ANew Hampshire 13.4 9.9 9 26.4 26.1 64.1 N/A 56.9 N/ANew York 15.4 12.9 23 43.6 22.8 64.5 18.5 57.7 24.3North Carolina 14.7 12.5 21 N/A 22.3 61.2 30.5 N/A 17.8North Dakota 11.0 9.3 5 21.3 29.0 63.6 37.2 60.8 17.3Ohio 13.1 13.9 27 32.1 N/A 67.6 31.5 62.6 N/AOklahoma 14.2 11.1 16 36.7 25.1 64.3 29.8 55.6 14.3Rhode Island 14.5 9.8 7 31.9 22.3 62.2 21.1 55.5 28.4

South Dakota 14.5 9.4 6 28.1 26.5 62.2 16.3 64.9 17.1Tennessee 14.8 15.2 30 44.3 24.0 61.1 28.7 50.7 18.1Texas†† 16.4 13.9 28 44.1 20.2 59.9 29.7 54.0 17.5Utah 11.3 7.0 1 22.9 29.3 71.1 25.8 62.9 20.3Vermont 14.1 10.8 13 N/A 26.6 65.4 14.6 N/A 26.5West Virginia 15.1 13.7 26 33.9 27.4 66.3 28.6 52.7 20.6Wisconsin 13.7 10.4 11 N/A 28.2 63.4 N/A 61.7 N/AWyoming 11.7 7.2 2 26.6 28.3 67.7 23.2 56.3 22.5

City out of 18 citiesBoston, MA 18.0 14.2 11 50.0 19.2 50.2 9.2 44.5 N/AChicago, IL 17.9 13.9 10 52.5 18.4 46.3 49.9 51.9 17.7Dallas, TX 19.9 15.9 16 57.5 16.2 54.2 11.2 46.6 16.1Dekalb County, GA 16.6 12.1 5 55.8 23.2 57.9 25.9 55.8 17.2Detroit, MI 19.5 19.9 18 65.0 22.4 49.8 28.5 N/A 18.5Dist. of Columbia 16.8 13.5 8 56.7 15.5 44.4 18.8 45.3 21.3

Ft. Lauderdale, FL 16.0 9.3 1 50.6 20.4 54.7 27.0 46.5 22.5Los Angeles, CA 17.0 15.8 14 50.4 20.8 58.8 51.0 47.9 19.1Memphis, TN 18.6 15.8 15 65.5 21.3 53.9 24.0 48.5 14.5Miami, FL 15.3 12.9 6 53.7 17.1 53.5 13.9 44.1 22.2Milwaukee, WI 19.3 16.2 17 N/A 23.0 52.3 N/A 51.5 N/ANew Orleans, LA 18.2 13.8 9 64.9 14.9 40.1 22.6 44.5 29.1

New York City, NY 16.2 13.3 7 59.1 22.9 61.0 48.9 45.5 25.9Orange County, FL 14.2 10.9 3 43.7 22.9 58.2 22.3 48.9 17.9Palm Beach, FL 14.9 11.2 4 44.2 20.8 57.9 18.8 49.4 23.1Philadelphia, PA 18.6 15.1 12 59.9 21.2 50.6 24.5 45.1 17.1San Bernardino, CA 20.6 15.4 13 51.5 22.2 57.3 48.0 49.8 18.9San Diego, CA 15.7 9.6 2 41.8 27.2 65.8 44.9 52.4 18.7

*Body mass index at or above the 85th percentile but below the 95th percentile of growth chart for age and sex. †Body mass index at or above the 95th percentile ofgrowth chart for age and sex. ‡Rank is based on % overweight. §During an average school day. ||Activities that did not make students sweat and breathe hard for 30 min-utes or more on 5 or more of the 7 days preceding the survey. ¶Activities that made students sweat and breathe hard for 20 minutes or more on 3 or more of the 7 dayspreceding the survey. #During the 12 months preceding the survey. **Had eaten 5 or more servings per day of green salad, potatoes (excluding French fries, fried potatoes,or potato chips), carrots or other vegetables, 100% fruit juice, or fruit during the 7 days preceding the survey. ††Survey did not include students from one of the state'slargest school districts. N/A = Data not available. Note: Data are not available for all states since participation in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System is a voluntarycollaboration between a state's departments of health and education.Source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, 2003, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(SS-2).

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

• Routinely promoting physical activity, includingunstructured play at home, in school, in childcaresettings, and throughout the community

• Encouraging parents and caregivers to promotehealthy eating patterns by offering nutritious snacks,such as vegetables and fruits, low-fat dairy foods, andwhole grains; encouraging children’s autonomy in self-regulation of food intake and setting appropriate lim-its on choices; and modeling healthy food choices

10 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

• Identifying children and adolescents in the health caresetting who are at risk due to family history, birthweight, or socioeconomic, ethnic, cultural, or environ-mental factors and tracking them annually by calcu-lating and plotting BMI

• Enlisting policymakers from local, state, and nationalorganizations and schools to support healthy lifestylesfor all children, including proper diet and adequateopportunities for regular physical activity

Television Viewing: A Modifiable Risk FactorWatching television is one modifiable factor that maycontribute to obesity in children.52 On average, childrenand adolescents spend more time in front of a televisionthan in any other activity besides sleeping.53 Televisionwatching competes with other activities that involvephysical activity. It bombards children and adolescentswith advertisements for high-calorie, low-nutrient foods,and it encourages between-meal snacking.54 The ThirdNational Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, con-ducted from 1988 to 1994, found that more than 25% ofchildren in the US watched at least 4 hours of televisionper day; children who watched 4 or more hours of tele-vision per day had a significantly greater body massindex than those who watched less than 2 hours perday.55 Having a television in a child’s bedroom is a strongpredictor of the child being overweight.44

Three or more hours oftelevision watching perday is considered indica-tive of sedentary behavior.The proportion of highschool students whowatch 3 hours or more oftelevision daily correlatedsignificantly with the pro-portion who were over-weight or at risk ofbecoming overweight inthe 28 states for whichdata were available in2003 (Figure 1E). Itshould be noted that theassociation between theprevalence of overweightyouth and the proportionof high school studentswho watch 3 or morehours of television per day

Figure 1E. Combined Youth Overweight* Versus Three or More Hours of Television Watching, by State, 2003

Wat

ched

th

ree

or

mo

re h

ou

rs o

f te

levi

sio

n p

er d

ay (

per

cen

t)

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

*Body mass index at or above the 85th percentile of growth chart for age and sex. Note: See Statistical Notes on page 47 for explanation of correlation.

Source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, 2003, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(SS-2).

Overweight and at risk for becoming overweight (percent)

R2 = 0.6028

p < 0.01

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 350

10

20

30

40

50

60

Body Mass Index (BMI) for Youth andAdolescentsAs children grow and mature, their body compositionchanges dramatically. The definitions of overweight andobesity are different for youth than for adults. Growthcharts showing the entire distribution of height, weight,and body mass index were revised in 200051 and areavailable at the CDC’s National Center for Health statisticsWeb site at www.cdc.gov/growthcharts. These growthcharts are the recommended approach to evaluate over-weight and obesity in children and youth. In this report,the following definitions are used:

• Overweight: 95th or higher percentile for BMI

• At risk of becoming overweight: 85th to 94th percentilefor BMI

replaced by more sedentary activities, such as playingvideo games, watching television or videotapes, or usinga computer. Although participation in organized sportsoffers many social and physical benefits to children whoparticipate,62 it is critical that schools and communitiesoffer a wide range of physical activities (i.e., dance, mar-tial arts, walking or running clubs) to all children, notonly to those who are athletic.

The potential influence of the physical environment onhealth has been recognized only recently.63 Urbansprawl, one aspect of the physical environment, reducesopportunities to walk or bike from home to school,shopping, or other destinations.64 According to the 2001National Household Travel Survey, children’s walkingtrips have declined by 60% since 1977; walking andbiking to school have declined by 50% since 1969.48 Arecent study found that fewer than 10% of WestVirginian students walked to school and that those whodid spent less than 10 minutes walking.65 In NorthCarolina, 12.1% of middle school and 6.4% of high schoolstudents walked or biked to school at least once a week,while only 3.5% of middle school and 1.6% of high schoolstudents walked to school 5 times a week.66 Distance,traffic safety, and fear of crime are factors that con-tribute to the declining rates of physical activity64,67 andthat must be addressed. Improvements in neighborhoodsafety are essential to provide children with opportuni-ties for physical activities.68

For many communities, environmental changes such asincreased housing density, walking and bicycle trails,and urban redesign will require long-term planning andinvestment.69 Recently, the Institute of Medicine rec-ommended that local governments, working with devel-opers and community groups, should increaseopportunities for physical activity by revising zoningordinances to increase availability and accessibility ofphysical activity in new developments, prioritizing capi-tal improvements to increase physical activity in existingareas, and building schools where they can be reachedsafely on foot by the communities they serve.50

One place to start fostering an environment that pro-motes physical activity is in schools, where childrenspend the majority of their time.70 A study conducted inSan Diego found that children in middle schools withadequate space, facilities, equipment, and supervisionwere 4 to 5 times more likely to be physically active atschool during free time than children in schools withinadequate space and supervision.71

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 11

does not prove causation. However, it does identify animportant issue for further study.

Television viewing has been associated with poor eatinghabits and greater consumption of fast food and softdrinks. One study found that daily servings of fruits andvegetables decreased significantly among adolescentswith each additional hour of television viewed per day.56

Physical ActivityThere are no national estimates of physical activity levelsamong children younger than 12 because self-reports inthis age group are less reliable than in older children oradolescents.57 Based on Youth Risk Behavior Sur-veillance System data from 2003, more than half of highschool students are considered vigorously active, and20%-25% are moderately active on a regular basis (Table1B). Nationally, 57.6% of high school students reportedplaying on one or more sports teams during 2003, withhigher participation rates among males (64.0%) thanfemales (51.0%).14

Limited data suggest that physical activity decreasesprogressively from ages 12 to 21.58 One longitudinalstudy has documented that only a small proportion ofUS adolescents who achieved the recommended amountof physical activity continued to do so into adulthood.59

Another longitudinal study reported substantialdeclines in physical activity levels among white andAfrican American girls from ages 9-10 to ages 19-20.60

The decrease was largest among African American girlsover the 10-year period. This study also found thatsmoking initiation in adolescence was associated with adecline in physical activity levels.60 Other factors con-tributing to declines in physical activity among youthinclude the increasingly sedentary nature of leisure-timeactivities, decreases in daily-living activities such aswalking or biking to school and doing household chores,and changes in availability and requirements of schoolphysical education programs.44,61 Vigorous physicalactivity, such as playing basketball, may have been

Many schools have increased time for academic instruc-tion and limited recess, unstructured playtime, andphysical education classes. Most school districts do notprovide time for daily physical education for students inkindergarten through 12th grades.11 In 2003, only 28.4%of high school students attended physical educationclass daily (Table 1B),14 down from 41.6% in 1991.72

Nationwide in 2000, only 8% of elementary schools, 6.4%of middle/junior high schools, and 5.8% of senior highschools provided daily physical education, althoughnearly three-quarters (71.4%) of elementary schoolsprovided regularly scheduled recess to all students.27

Results from a recent study suggest that participation inschool-based physical activity may help to prevent over-weight in youth. The study followed a nationally repre-sentative cohort of children from kindergarten to first

grade and found that increasing physical educationinstruction time by one hour in first grade comparedwith kindergarten significantly reduced BMI amonggirls who were overweight or at risk for overweight.73

This effect was not seen among boys due to boys beingmore active than girls at young ages. Furthermore, thestudy estimated that if school physical education pro-grams nationwide were expanded so that every kinder-garten child receives a minimum of 5 hours of PEinstruction weekly, the prevalence of overweight amonggirls could be decreased by 43% and the prevalence ofchildren who are at risk for overweight could bedecreased by 60%.73 Parents can advocate for schoolpolicies that require daily physical education or thatencourage the development of competitive and non-competitive activities.74

12 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

Success StoriesWith the increasing recognition of childhood obesity, manyprograms have begun to address the problem. This sectionhighlights some of these efforts.

CDC’s Kids Walk-to-School ProgramSince only 1 out of every 10 trips to school are made by walk-ing or bicycling, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC)’s Kids Walk-to-School program seeks to increase oppor-tunities for daily physical activity by encouraging children towalk to and from school in groups accompanied by adults.75

Another goal of the program is to encourage communities to create an environment that supports safe walking and biking to school. The online guide (available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/kidswalk) provides step-by-step details on howto organize a Kids Walk-to-School Program, including safetyinformation and an extensive list of resources to assist withprogram development.

The PATH ProgramPATH (Physical Activity and Teenage Health) is a school-basedintervention focused on urban teenage girls in New York Citythat has shown significant improvements in heart healthknowledge, eating habits, percentage of body fat, and bloodpressure compared with traditional school physical educationprograms.76 The PATH program presents a school-based healthpromotion and personal wellness program intended to reducethe occurrence of unhealthy behaviors, and to prevent theonset of risk factors for coronary artery disease among urbangirls through an integrated program of exercise and hearthealth-related education. Many of the risk factors addressed bythis program also apply to cancer.

CDC’s VERBTM CampaignVERB, a 5-year media campaign initiated by the CDC inOctober 2002, promotes physical activity through research,media, partnership, and community efforts. VERB advertise-ments aimed at children portray physical activity as being“cool,” fun, and socially appealing, while advertisementsaimed at parents encourage them to engage in physical activ-ity with their children and suggest ways to overcome perceivedbarriers to physical activity. This campaign also addresses otherimportant environmental factors, such as access to safe andaffordable opportunities for both leisure-time and organizedphysical activities.

The outcomes of this media campaign are being measured 3times by the Youth Media Campaign Longitudinal Survey(YMCLS), a telephone survey of children aged 9 to 13 and theirparents. Baseline data from spring 2002 showed that whilemost participants engage in some free-time physical activity(77.4%), the majority of children 9-13 years do not participatein any organized physical activity outside of school (61.5%).Data from the spring 2003 and spring 2004 surveys have notbeen published. However, initial evaluation data from thespring 2003 survey indicate that the program shows potentialin shrinking the gap in physical activity levels between boys andgirls. Communities receiving enhanced levels of VERB market-ing activity showed even more promise. Future YMCLS reportswill provide more insight into the effectiveness of the mediacampaign. More information about the VERB campaign is avail-able at www.cdc.gov/youthcampaign.

While these results are encouraging, continued awareness andincreased participation rates in both free-time and organizedphysical activities are needed to curb the youth obesityepidemic.

Several new initiatives are attempting to consolidate andmake available resources to help individuals, communi-ties, organizations, and politicians address the obesityproblem of America’s youth.

• SAY (Shaping America’s Youth) is a nationwideinfrastructure that has begun to identify and central-ize information about organizations, agencies, andbusinesses that address inactivity and obesity amongyouth. More than 1,800 active programs, representingall 50 states, have registered to be included in thesearchable database available at www.shapingameric-asyouth.com.

• Action for Healthy Kids (AFHK) assists schools infinding solutions to improve students’ health andreadiness to learn through daily physical activity,quality health and physical education, and increasedavailability of healthy foods and beverages. A reportfrom the AFHK program documenting successes inimproving school attendance, raising standardizedtest scores, and reducing behavior problems can beaccessed at www.actionforhealthykids.org.

• PAY (Physical Activity for Youth Policy Initiative)provides advocates and policymakers with the ration-ale, recommended policy options, and examples ofcurrent programs, legislation, or laws in order to assistwith the integration of physical activity awareness andaction in afterschool programs, community programs,community design, and school programs. The docu-ment and accompanying policy resource guide can be obtained at www.ncppa.org/publicaffairspolicy_index.asp.

Healthy Eating PatternsMajor changes in the diet of youth have been docu-mented over the past 2 decades, including increases inoverall energy intake, added sugars, sodium, soft drinks,fruit juices, and fast foods and decreases in the amountsof fruits, vegetables, and milk consumed.77-79 Snack foodconsumption has doubled in the last 20 years, andAmerican children are consuming more meals awayfrom home.78,80 Less than one-fourth (22%) of US highschool students ate 5 or more servings of vegetables andfruits per day in 2003 (Table 1B).

Among the recommendations to improve eating pat-terns among children and adolescents are to: 1) limitchildren’s consumption of fast foods; 2) promote health-ier food choices in school cafeterias; 3) decrease avail-ability and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages;and 4) limit and monitor food and beverage advertisingto children.6,44,50

1. Limit children’s consumption of fast foods.

Meals eaten away from home are generally less healthythan home-cooked food.78 Research shows that 30% ofchildren and adolescents consume fast food on a typicalday.81 Children who eat fast food consume more totalcalories, total fat, and added sugars, as well as moresugar-sweetened beverages, less milk, and fewer fruitsand nonstarchy vegetables.81 A recent study found thatwhen eating fast food, adolescents, regardless of theirbody weight, tended to eat too much, consuming roughly60% of their estimated total daily caloric needs in asingle sitting.82 Unlike leaner participants, those whowere overweight did not reduce their energy intakeduring the rest of the day, consuming an average of 400excess calories. Eating fast food may maintain or exacer-bate obesity.82 Parents should limit their children’sconsumption of fast food and ensure that healthy foodchoices are available and accessible at home for mealsand snacks.83

2. Promote healthier food choices in school cafeterias.

Foods high in fat, sugar, sodium, and calories are not onlypopular among adolescents but also generate substan-tial revenue for schools.84 In 43% of elementary schools,74% of middle schools, and 98% of high schools, studentshave access to vending machines and/or snack barswhere they can purchase food or beverages that are highin fat, salt, and added sugar.27 A study of students transi-tioning from elementary to junior high (where theygained access to school snack bars) documented dra-matic decreases in the consumption of fruit (33%),

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 13

vegetables (42%), and milk (35%), while the amount offried vegetables and sweetened beverages consumedincreased by 68% and 62%, respectively.85 Another studyfound that students attending schools without “a lacarte” programs consumed a diet higher in fruits andvegetables compared with students who had access to “ala carte” programs.86 This study also found that students’mean intake of fruit and vegetable servings declined by11% for each additional snack vending machine presentin a school.86

3. Decrease availability and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, including soft drinks.

Between 56% and 85% of school-age children consumeat least one nondiet soft drink daily, adding calories withno nutritive value to their diet.87 A 19-month follow-upstudy of Massachusetts school children found significantincreases in both body mass index (BMI) and obesity foreach additional daily serving of a sugar-sweeteneddrink.88 A longitudinal study of adolescents found thatsoda consumption was significantly related to BMI.89

NHANES data also shows that the contribution of softdrinks to total energy (calorie) intake is highest amongoverweight children.90 A targeted, school-based educa-tional intervention that reduced the number of carbon-ated drinks consumed also prevented further weightgain in the children compared to the controls.91

One intervention that has been adopted by a number ofschool districts (including Los Angeles, New York City,Oakland, and Philadelphia) is to eliminate sales of sugar-sweetened drinks in schools. A report issued from the USGeneral Accounting Office stated that food sales werethe most prevalent form of commercial activity in

14 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

Success StoriesUSDA’s Fruit and Vegetable Pilot Program(FVPP)The USDA (a partner in the 5 A Day for Better HealthProgram) created the FVPP through a $6 million grant fromthe 2002 Farm Act to provide fresh and dried fruits andvegetables free to children in 107 elementary and second-ary schools in 4 states as well as in 1 tribal organization.These foods are delivered through classroom service,kiosks, and free vending machines. Schools participating ina 1-year pilot program reported that 80% of studentswere very interested in the program and that more than90% of fruit and vegetable offerings were consumed.One-third of the schools reported that the programincreased the likelihood of student participation in theschool meal program, and almost 80% of schools reportedthat the program increased the acceptance of fruits andvegetables offered as part of school meals. Virtually all ofthe schools advocated for continuation of the program,and in June of 2004, Congress passed legislation makingthe program permanent and expanding it to include 8states and 3 tribal organizations with an additional $3 mil-lion in annual funding.96 For more information about thisand other 5 A Day for Better Health programs, see page32 in the adult section on fruit and vegetable consumptionor visit www.5aday.gov.

TACOS (Trying Alternative Cafeteria Optionsin Schools)TACOS is a high-school-based intervention that was ableto increase the number of lower-fat “a la carte” foodoptions by 50% in target schools located in theMinneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. The program doc-umented increased sales of these foods and increasedacceptability of lower-fat foods by students and schoolpersonnel. The findings indicate that changes in the schoolenvironment can positively influence food choices with noadverse effects on food service revenues.97

Florida – Eat Your Colors EverydayThis school-based pilot program, initiated in 2002 througha grant from the Florida Department of Agriculture andConsumer Services, has continued to expand throughoutFlorida and into other states across the nation (Kansas,Oregon, and South Carolina in 2003-2004). The programis designed to increase student consumption of fresh fruitsand vegetables by implementing, enhancing, and expand-ing salad bars, salad options, and nutrition educationactivities in elementary, middle, and high schools.Evaluations of the pilot program found an increase instudent fruit and vegetable consumption ranging from 9%to 31% at the school level, as well as an increase in thepercent of students eating more than 50% of their fruitsand vegetables following the intervention. More informa-tion can be obtained at www.5aday.com/html/industry/floridastats.php.

schools; these were primarily soft drinks sold from vend-ing machines and at fundraising events.92 Fifty percentof school districts have contracts with companies thatallow the companies to sell soft drinks in the schools andto advertise in schools and on school grounds. In return,schools and districts receive incentives and/or a per-centage of the sales revenue.27 Only 19 states havepolicies regarding commercial marketing activities inschools.92 A new policy statement from the AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics recommends that school districtsconsider restricting the sale of soft drinks to safeguardagainst health problems that result from overconsump-tion among children.87 Nutritious alternatives such aswater, real fruit juice, and low-fat milk can be sold inplace of soft drinks to help maintain school revenues.87

4. Limit and monitor food and beverage advertisingto children.

Studies have reported that students in grades 7-12 whofrequently eat fast food tend to watch more televisionthan other students93 and that middle-school childrenwho watch more television tend to consume more softdrinks.94 One factor that may explain these associationsis increased exposure to youth-directed food advertisingamong children who watch more television. A study offood advertising directed at youth during Saturdaymorning children’s television programming found thatalmost one-third of the ads were for foods high in fat andsugar, such as candy, soft drinks, chips, cookies, fastfoods, and high-sugar breakfast cereals. During this timeframe, an estimated exposure to food advertising occursonce every 5 minutes.95 The Institute of Medicine hasrecommended that national guidelines be developedconcerning food and beverage advertising and market-ing to children. These guidelines would be implementedby industry and monitored by the Federal TradeCommission.50

Sun ProtectionThe vast majority of skin cancers are due to unprotectedand excessive ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure. WhileUV exposure is associated with a small percentage of allcancer deaths,98 the American Cancer Society estimatesthat UV exposure is associated with more than 1 millioncases of basal and squamous cell cancers and 59,580cases of malignant melanoma annually.1 Artificialsources, such as tanning booths, add to UV exposure.The short-term adverse effects from unprotected UVexposure are sunburn and tanning, while long-termexposure can cause prematurely aged skin, wrinkles, andskin cancer. Though it was once believed that dark

brown or black skin prevented melanoma, more recentresearch indicates that darker-skinned people candevelop this cancer, especially on the hands, soles of thefeet, and under the nails.

Regular practice of sun protection behaviors can lead tosignificant reductions in sun exposure and risk of skincancer (see sidebar on page 16). Sunburn during child-hood and intense, intermittent sun exposure increasethe risk of melanoma and other skin cancers.99-101

Because much exposure to sunlight occurs during child-hood and adolescence, protection behaviors shouldbegin early in life. However, a CDC study revealed that25% of parents did not require their children aged 12 oryounger to use sun protective behaviors, and the pro-portion of children who used one or more protectivebehaviors decreased with age.102

Adolescence is a period of heightened unprotected sunexposure.103 An American Cancer Society study showedthat less than one-third of youth aged 11 to 18 used anytype of sun protection measures.104 The Youth RiskBehavior Surveillance System found that only 15% ofpublic and private high school students used sunscreenof SPF 15 or higher “most of the time” or “always” whenthey were outdoors in the sun for more than an hour.105

In another study, almost three-quarters (72%) of youthreported getting sunburned during the summer months.Of those, more than one-third (39%) reported usingsunscreen lotion of SPF 15 or higher when they gotburned.106 It is important that adolescents be educatedabout proper application and re-application intervals forsunscreen.107,108

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 15

To improve sun protection practices among children andadolescents, the CDC has made recommendations todevelop comprehensive programs that include schoolintervention components.109 However, policies for sunsafety programs do not exist in the majority of elemen-

tary, junior/middle, or senior high schools (Figure 1F). Instates where UV exposure is high year-round, parentsshould work with schools to develop sun protectionprograms at all grade levels and should establish propersun protection practices for their own children.

16 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School Health Policies and Programs Study, 2000. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Figure 1F. Policies for Required Sun Safety or Skin Cancer Prevention in Schools, by State, 2000

AL

AZAR

CA CO

CT

DE

FL

GA

ID

IL IN

IA

KS

KY

LA

ME

MD

MA

MI

MN

MS

MO

MT

NENV

NH

NJ

NM

NY

NC

ND

OH

OK

OR

PA

RI

SC

SD

TN

TX

UT

VT

VA

WA

WV

WIWY

DC

HI

AK

Elementary and middle or high schools

Middle or high schools only

No policies

Risk Factors and Prevention Measures for Melanoma and Other Skin Cancers

Risk factors for melanoma110

• Light skin color

• Family history of melanoma

• Personal history of melanoma

• Presence of moles and freckles

• History of severe sunburn occurring early in life

Risk factors for basal and squamous cell cancers110

• Chronic exposure to the sun

• Family history of skin cancer

• Personal history of skin cancer

• Light skin color

Measures to prevent skin cancer• Avoid direct exposure to the sun between the hours

of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., when ultraviolet rays are themost intense.

• Wear hats with a brim wide enough to shade the face, ears, and neck, as well as clothing thatcovers as much as possible of the arms, legs, andtorso.

• Cover exposed skin with a sunscreen lotion with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher.

• Avoid tanning beds and sun lamps, which providean additional source of UV radiation.

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 17

Tobacco UseTobacco use is the single largest preventable cause ofdisease and premature death in the US. Each year,according to the Surgeon General, it accounts for an esti-mated 440,000 premature deaths related to smoking,38,000 deaths in nonsmokers as a result of exposure tosecondhand smoke, and $157.7 billion in health-relatedeconomic losses.111 Tobacco use causes increased risk ofcancer of the lung, mouth, nasal cavities, larynx, phar-ynx, esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, kidney, bladder,and uterine cervix, as well as myeloid leukemia.112 Thirtypercent of cancer deaths, including 87% of lung cancerdeaths, can be attributed to tobacco (Figure 2A).2,112,113

Both cigarette consumption and the prevalence of smok-ing in the US have declined since the release of the firstUS Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health in1964, although recent decreases have been greater fortobacco consumption than for prevalence.114 Per-capitacigarette consumption is currently lower than at anypoint since the start of World War II. Nonetheless, an

estimated 25% of men and 20% of women still smokecigarettes, with approximately 82% of these individualssmoking daily.115

Smoking prevalence varies by level of education.Interestingly, though, this relationship has reversed overtime. In the early 1960s, college-educated adults had thehighest smoking prevalence. By 2002, only 9.9% of collegegraduates were current smokers, compared to 31% ofthose who did not graduate from high school (Figure2B).116 Smoking prevalence is higher among men thanwomen, and varies by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomicstatus (Table 2A). The prevalence of smoking is highest

Adult Cancer PreventionC

ance

r si

te

Figure 2A. Annual Number of Cancer Deaths* Attributable to Smoking, Males and Females, by Site, US, 1995-1999

*Among men and women 35 and older.

Source: US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health, 2004. American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

0 20 40 60 80 100

Male

Number of deaths (in thousands)

Oropharynx

Esophagus

Stomach

Pancreas

Larynx

Lung

Bladder

Kidney

Myeloid leukemia

Can

cer

site

0 20 40 60 80 100

Female

Number of deaths (in thousands)

Oropharynx

Esophagus

Stomach

Pancreas

Larynx

Lung

Bladder

Kidney

Myeloid leukemia

Cervix

Attributable to cigarette smoking

Other causes

18 Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005

among American Indian/Alaska Native men andwomen, and lowest among Asian American men andwomen.115 Across the states, smoking prevalence rangesfrom 12% in Utah to 31% in Kentucky (Table 2B).

Comprehensive Tobacco ControlFurther reductions in tobacco use will require imple-mentation of economic, policy, and regulatory interven-tions that reduce tobacco use and protect nonsmokersfrom secondhand smoke.5 The goals of comprehensivetobacco control5 are to:

• Prevent the initiation of tobacco use among youngpeople

• Promote quitting among young people and adults

• Eliminate nonsmokers’ exposure to environmentaltobacco smoke (ETS)

• Identify and eliminate the disparities in tobacco useand its effects among different population groups

• Facilitate smoking cessation

Best practices for comprehensive state tobacco controlprograms have been published by the Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention (CDC).117 The CDC recommendsthat states establish tobacco control programs that arecomprehensive, sustainable, and accountable. Effectivestate-based programs include the following compo-nents: community and school programs and policies,

Table 2A. Current Cigarette Use*, Adults 18and Older, US, 2002

Characteristic % Men % Women % Total

Age group (years)18 to 24 32.4 24.6 28.525 to 44 28.7 22.8 25.745 to 64 24.5 21.1 22.765 or older 10.1 8.6 9.3

Race/EthnicityWhite (non-Hispanic) 25.5 21.8 23.6African American (non-Hispanic) 27.1 18.7 22.4Hispanic/Latino 22.7 10.8 16.7American Indian/Alaska Native† 40.5 40.9 40.8Asian American‡ 19.0 6.5 13.3

Education (years)§

8 or fewer 25.4 13.5 19.39 to 11 38.1 30.9 34.112 29.8 22.1 25.613 to 15 24.8 21.6 23.116 or more 13.6 10.5 12.1more than 16 7.8 6.4 7.2

Total 25.2 20.0 22.5

*Persons who reported having smoked at least 100 cigarettes or moreand who reported now smoking every day and/or some days.†Estimates should be interpreted with caution because of the smallsample sizes. ‡Does not include Native Hawaiians and other PacificIslanders. §Persons aged 25 or older.

Source: National Health Interview Survey, 2002, National Center forChronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults – UnitedStates, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(20):427-431.

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

Figure 2B. Current* Cigarette Smoking by Education, Adults 25 and Older, 1974-2002

Perc

ent

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

*Adults 25 and older who have ever smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and who are current smokers (regular and irregular).

Source: National Health Interview Survey, 1974-2002, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(20):427-431.

No high school degree

College degree

Some college

Year

High school degree

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

200220012000199919981997199519941993199219911990198819871985198319791974

Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2005 19

Table 2B. Tobacco Use, Adults 18 and Older, 2003, and Comprehensive Tobacco Control Measures, by State,2001, 2004, and 2005

Cigarette Smoking* Fiscal year Fiscal year Difference in per% Men % Women % 2001 per capita 2005 per capita capita tobacco Cigarette

% 18 State 18 and 18 and Low tobacco control tobacco control control funding tax perand older rank† older older education‡ funding ($) funding ($) (2001-2005) pack ($)§

Alabama 25.35 39 28.54 22.45 33.35 1.35 0.08 -1.27 0.425Alaska 26.30 47 30.32 21.93 46.34 2.23 6.70 4.47 1.60||

Arizona 20.95 15 23.78 18.17 21.73 6.72 4.50 -2.22 1.18¶

Arkansas 24.84 36 27.59 22.31 36.65 6.02 6.58 0.56 0.59#

California 16.80 2 20.48 13.20 17.15 3.38 2.18 -1.20 0.87

Colorado 18.55 4 19.61 17.48 33.00 2.95 1.00 -1.95 0.20Connecticut 18.75 5 19.67 17.90 25.99 0.29 0.02 -0.27 1.51#

Delaware 21.94 22 25.99 18.23 31.92 3.57 11.87 8.30 0.55#

Dist. of Columbia 22.33 27 26.15 19.00 27.84 0.00 0.00 0.00 1.00Florida 23.95 33 25.98 22.06 29.95 2.75 0.06 -2.69 0.339

Georgia 22.82 30 25.84 19.97 36.02 1.93 1.40 -0.53 0.37#

Hawaii 17.26 3 20.08 14.45 22.24 7.68 7.35 -0.33 1.40||

Idaho 18.98 6 19.52 18.46 33.71 0.93 1.47 0.54 0.57#

Illinois 23.41 31 27.18 19.90 27.22 2.30 0.89 -1.41 0.98¶

Indiana 26.14 45 28.57 23.84 38.42 5.76 1.78 -3.98 0.555¶

Iowa 21.74 21 22.83 20.71 31.62 3.21 1.74 -1.47 0.36Kansas 20.36 13 21.04 19.72 32.61 0.19 0.28 0.09 0.79¶

Kentucky 30.85 51 33.77 28.13 38.61 1.44 0.67 -0.77 0.03Louisiana 26.58 48 30.28 23.22 33.29 0.92 2.53 1.61 0.36¶

Maine 23.60 32 23.12 24.05 39.54 14.75 11.14 -3.61 1.00

Maryland 20.21 12 22.98 17.69 35.32 5.66 1.79 -3.87 1.00¶

Massachusetts 19.16 7 20.02 18.38 26.04 6.79 0.60 -6.19 1.51¶

Michigan 26.16 46 30.24 22.35 37.76 0.00 0.00 0.00 2.00||

Minnesota 21.11 17 22.35 19.92 31.69 7.11 3.80 -3.31 0.48Mississippi 25.63 43 31.10 20.67 30.37 10.90 7.03 -3.87 0.18

Missouri 27.32 49 31.15 23.82 35.30 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.17Montana 19.92 11 19.50 20.33 32.44 3.88 2.77 -1.11 0.70#

Nebraska 21.27 19 23.60 19.05 26.16 4.09 1.69 -2.40 0.64¶

Nevada 25.19 38 28.97 21.31 30.84 1.50 2.20 0.70 0.80#

New Hampshire 21.24 18 22.37 20.16 33.71 2.43 0.00 -2.43 0.52

New Jersey 19.48 8 21.17 17.91 23.99 3.57 1.31 -2.26 2.40||

New Mexico 21.96 23 23.56 20.46 33.18 1.26 2.75 1.49 0.91#

New York 21.63 20 24.78 18.79 24.12 1.58 2.08 0.50 1.50¶

North Carolina 24.83 35 27.96 21.87 32.38 0.00 1.86 1.86 0.05North Dakota 20.47 14 21.98 19.00 23.22 0.00 4.83 4.83 0.44

Ohio 25.39 40 26.93 23.98 35.91 5.28 4.69 -0.59 0.55¶

Oklahoma 25.17 37 27.79 22.72 35.16 1.83 1.39 -0.44 0.23Oregon 20.96 16 23.10 18.90 27.61 2.48 1.02 -1.46 1.18Pennsylvania 25.52 41 27.06 24.13 33.66 0.00 3.75 3.75 1.35||

Rhode Island 22.40 28 23.83 21.12 25.45 2.19 2.38 0.19 2.46||

South Carolina 25.53 42 28.49 22.81 34.87 0.45 0.00 -0.45 0.07South Dakota 22.67 29 24.70 20.72 22.73 2.25 1.99 -0.26 0.53#

Tennessee 25.70 44 27.30 24.23 39.10 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.20¶

Texas 22.10 26 26.73 17.62 24.97 0.45 0.35 -0.10 0.41Utah 11.95 1 13.99 9.93 32.87 2.69 3.13 0.44 0.695¶

Vermont 19.58 10 19.82 19.36 31.11 10.68 7.72 -2.96 1.19¶

Virginia 22.06 24 26.41 17.98 38.34 1.78 1.84 0.06 0.20||

Washington 19.54 9 20.93 18.19 29.03 2.54 4.61 2.07 1.425¶

West Virginia 27.39 50 27.60 27.19 28.72 3.26 3.26 0.00 0.55#

Wisconsin 22.07 25 23.97 20.25 30.98 3.95 1.86 -2.09 0.77Wyoming 24.63 34 25.17 24.09 40.64 1.82 7.70 5.88 0.60#

United States** 22.32 25.06 19.74 28.73 3.11 2.76 -0.36 0.46Range 11.95-30.85 13.99-33.77 9.93-28.13 17.15-46.34 0.0-14.75 0.0-11.87 -6.19-8.30 0.03-2.46

*Adults 18 and older who have smoked 100 cigarettes and are current smokers (regular and irregular). †Rank is based on % 18 and older. ‡Adults 25 and older with lessthan a high school education. §Taxes reported as of September 2004. ||Passed tax increase legislation in 2004. ¶Passed tax increase legislation in 2002. #Passed tax increaselegislation in 2003. **See Statistical Notes on page 47 for definition of prevalence measures; average value (including District of Columbia) for taxes and per capita funding.

Source: Cigarette smoking percentages: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Public Use Data Tape 2003, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and HealthPromotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004. Per Capita Funding: calculated by dividing state prevention funding (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, et al. A Broken Promise to Our Children. The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement Five Years Later, National Center for Tobacco-Free Kids, 2004) by US Census state populationcounts (http://www.census.gov). Cigarette Taxes: American Cancer Society. Unpublished information as of October 2004. Washington (DC): American Cancer Society,National Government Relations Department, 2004.

American Cancer Society, Surveillance Research

smoke-free policies, counter-marketing campaigns(such as antismoking tobacco ads), and cessation pro-grams and policies (smoking cessation quitlines, bene-fits coverage for tobacco cessation therapies).117

Evidence that supports these recommendations stemsin part from efficacy studies in states that have imple-mented such programs (including California,Massachusetts, Oregon, Maine, Florida, Minnesota, andMississippi).5 These studies document the beneficialimpact of comprehensive tobacco control programs inreducing tobacco use and consumption.118-127 In a studyof the California Tobacco Control Program (CTCP),begun in 1990, analyses of lung cancer incidence inCalifornia between 1975 and 1999 found that there was asignificantly greater rate of decline in lung cancer casesduring the period of 1988 to 1999 than would have beenpredicted from prior lung cancer trends in the state. Thisdecline was also much greater than declines in lungcancer incidence trends (if any) in other areas, measuredby SEER.127 The CTCP has estimated that for every dollarspent on tobacco control between 1990 and 1998, morethan $3.00 was saved in direct medical costs.128