Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

-

Upload

bob-andrepont -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

1/85

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

2/85

Front Cover:The Tay Ninh Provincial Reconnais-sance Unit near Nui Ba Den Mountain in 1969.Then-Captain Andrew R. Finlayson, the author ofthis book, is on the bottom left.

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

3/85

MARINE ADVISORS

WITH THE VIETNAMESE PROVINCIALRECONNAISSANCE UNITS, 1966-1970

by

Colonel Andrew R. Finlayson

U.S. Marine Corps (Retired)

Occasional Paper

HISTORY DIVISIONUNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

QUANTICO,VIRGINIA

2009

Third Printing

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

4/85

ii

Other Publications in the Occasional Papers Series

Vietnam Histories Workshop: Plenary Session. Jack Shulimson, editor. 9 May1983. 31 pp.

Vietnam Revisited; Conversation with William D. Broyles, Jr. Colonel John G. Miller, USMC, editor. 11December 1984. 48 pp.

Bibliography on Khe Sanh USMC Participation. Commander Ray W. Strubbe, CHC, USNR (Ret), com-piler. April 1985. 54 pp.

Alligators, Buffaloes, and Bushmasters: The History of the Development of the LVT Through World War

II.Major Alfred Dunlop Bailey, USMC (Ret). 1986. 272 pp.

Leadership Lessons and Remembrances from Vietnam. Lieutenant General Herman Nickerson, Jr.,USMC (Ret). 1988. 93 pp.

The Problems of U.S. Marine Corps Prisoners of War in Korea. James Angus MacDonald, Jr. 1988.

295 pp.

John Archer Lejeune, 1869-1942, Register of His Personal Papers.Lieutenant Colonel Merrill L. Bartlett,USMC (Ret). 1988. 123 pp.

To Wake Island and Beyond: Reminiscences. Brigadier General Woodrow M. Kessler, USMC (Ret).1988. 145 pp.

Thomas Holcomb, 1879-1965, Register of His Personal Papers. Gibson B. Smith. 1988. 229 pp.

Curriculum Evolution, Marine Corps Command and Staff College, 1920-1988. Lieutenant ColonelDonald F. Bittner, USMCR. 1988. 112 pp.

Herringbone Cloak-GI Dagger, Marines of the OSS. Major Robert E. Mattingly, USMC. 1989. 315 pp.

The Journals of Marine Second Lieutenant Henry Bulls Watson, 1845-1848. Charles R. Smith, editor.1990. 420 pp.

When the Russians Blinked: The U.S. Maritime Response to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Major John M.Young, USMCR. 1990. 246 pp.

Marines in the Mexican War.Gabrielle M. Neufeld Santelli. Edited by Charles R. Smith. 1991. 63 pp.

The Development of Amphibious Tactics in the U.S. Navy. General Holland M. Smith, USMC (Ret).1992. 89 pp.

James Guthrie Harbord, 1866-1947, Register of His Personal Papers. Lieutenant Colonel Merrill L.Bartlett, USMC. 1995. 47 pp.

The Impact of Project 100,000 on the Marine Corps. Captain David A. Dawson, USMC. 1995. 247 pp.

Marine Corps Aircraft: 1913-2000. Major John M. Elliot, USMC (Ret). 2002. 126 pp.

Thomas Holcomb and the Advent of the Marine Corps Defense Battalion, 1936-1941. David J. Ulbrich.2004. 78 pp.

Marine History Operations in Iraq,Operation Iraq Freedom I, A Catalog of Interviews and Recordings.LtCol Nathan S. Lowrey, USMCR. 2005. 254 pp.

With the 1st Marine Division in Iraq, 2003. No Greater Friend, No Worse Enemy.LtCol Michael S. Groen, USMC, 2006. 413 pp.

Occasional Papers

The History Division has undertaken the publication for limited distribution of various studies, theses,compilations, bibliographies, monographs, and memoirs, as well as proceedings at selected workshops,seminars, symposia, and similar colloquia, which it considers to be of significant value for audiences in-terested in Marine Corps history. These Occasional Papers, which are chosen for their intrinsic worth,must reflect structured research, present a contribution to historical knowledge not readily available in pub-lished sources, and reflect original content on the part of the author, compiler, or editor. It is the intent ofthe Division that these occasional papers be distributed to selected institutions, such as service schools,official Department of Defense historical agencies, and directly concerned Marine Corps organizations, sothe information contained therein will be available for study and exploitation.

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

5/85

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface .............................................................................................................................v

Acknowledgments .........................................................................................................vii

Introduction.....................................................................................................................1

The Beginning..................................................................................................................3

PRU Organization, Recruitment, Equipment, and Command and Control ......................8

Sergeant Paul C.Whitlock: One of the First and Best, 1966-67 .....................................14

Sergeant Ronald J.Lauzon: Hue City, 1967 ....................................................................16

Staff Sergeant Wayne W. Thompson: Leadership Challenges and Spies, 1967-68..........20

First Lieutenant Joel R.Gardner: A Marine in II Corps, 1967-68....................................22

Lieutenant ColonelTerence M.Allen: The Perspective from Saigon, 1968-70 ...............27

Death at the Embassy House: Tet, 1968.........................................................................29

Sergeant Rodney H.Pupuhi: I Corps, Post-Tet 1968......................................................40

First Lieutenant Douglas P. Ryan: I Corps, 1968-69........................................................43

Capt Frederick J.Vogel: I Corps, 1969 ...........................................................................45

A Typical Operational Scenario: Tay Ninh, 1970............................................................47

Conclusions ...................................................................................................................52

Lessons Learned.............................................................................................................55

Sources...........................................................................................................................61

Bibliography...................................................................................................................63

Appendix: U.S. Marine Provincial Reconnaissance Unit Advisors.................................65

Endnotes ........................................................................................................................69

iii

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

6/85

iv

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

7/85

Preface

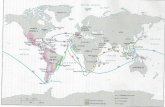

U.S.Marines as advisors have a long history,from Presley OBannon atTripoli through Iraq andAfghanistan via Haiti, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, China, South Korea,Taiwan, Philippines,and Vietnam. While most Marines think of the Vietnamese Marine Corps as the primary advisory

experience during that conflict, others served with various other advisory programs with theU.S.Army,U.S.Navy,U.S.Joint Special Operations,and U.S.Civil Operations and Rural DevelopmentSupport. One of these is the subject of this study: Marine advisors with the Vietnamese Provin-cial Reconnaissance Units (PRUs). This narrative is a combination of experience, research, andreflection. While other journalistic or academic accounts have been published,this is a narrativeof participants.

Many historians consider the two most effective counterinsurgency organizations employedduring the Vietnam War to have been the PRU and USMC Combined Action Platoons (CAP). Inboth cases,U.S.Marines played a significant role in the success of these innovative programs. Itshould be pointed out,however,that the number of U.S.Marines assigned to these programs wassmall and the bulk of the forces were locally recruited fighters. Both programs used a small cadreof Marines providing leadership, training, and combat support for large numbers of indigenous

troops, and in so doing, capitalized on the inherent strengths of each.

The author believes that both of these programs have applicability in any counterinsurgencywhere U.S. forces are called upon to assist a host government. Obviously, adjustments to theseprograms would have to be made to take into account local conditions, but the core concept ofproviding U.S.Marines to command or advise local militia and special police units is one that hasgreat promise for success. With a clear understanding of why the PRUs and CAPs worked, andwith the necessary adjustments to take into account local conditions,similar units can be createdto defeat future insurgencies. With this in mind,the author hopes that this work will provide U.S.military planners with insights into creating and managing units capable of defeating a well-or-ganized and highly motivated insurgent political infrastructure.

v

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

8/85

vi

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

9/85

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank several people who were instrumental in the creation of this work andwhose assistance allowed me to overcome many obstacles to acquiring firsthand accounts ofU.S. Marines who served as advisors with the Provincial Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) program.

First, I would like to thank General James N. Mattis for suggesting that I write this work. GeneralMattis felt that this book would serve as a means of capturing important counterinsurgencylessons learnedduring the Vietnam War, and in so doing, provide valuable insights for present-day Marines as they fight other insurgencies in other lands.

Second, I wish to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Mark Moyar, the author of the most objec-tive and accurate book concerning the Phoenix program, Phoenix and the Birds of Prey. Dr.Moyar was the first historian of note to do the kind of thorough research into the Phoenix pro-gram needed to strip away the misunderstandings surrounding this counterinsurgency program.I am indebted to him for his support and insights during the creation of this work.

One individual, Lieutenant Colonel (Ret) George W.T.Digger ODell, provided invaluable as-sistance to me by putting me in touch with former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officers

who had been involved with the PRU and could provide information on how the CIA viewed thecontribution of the military assignees to the program.Lieutenant Colonel ODell served in the Ma-rine Corps from 1965 to 1968, and then left the Marine Corps to join the CIA as a paramilitaryofficer in Laos and the Middle East from 1969 to 1975,before returning to the Marine Corps tofinish his career in 1992 as one of the Corps few experts in the area of special warfare. He wastireless in his efforts to introduce me to his many friends in the CIA who had knowledge of thePRU Program.

I was ably assisted with the editing and formatting of this work by two longtime friends andcolleagues, Hildegard Bachman and Mary Davisson. They provided many professional and valu-able suggestions on how to improve the content and appearance.

I would like to thank several former CIA officers who provided valuable background material

on the Phoenix program, the PRUs,and contact information on the Marines who served as advi-sors. They are Rudy Enders,Ray Lau, Hank Ryan,Warren H.Milberg,William Cervenak,and CharlesO. Stainback. These patriots served their country in silence, often in extremely dangerous as-signments, and I am both indebted to them for their assistance with this paper and for their un-sung service to our nation.

At the Histor y Division, Chief Historian Charles D.Melson provided project guidance, with ed-iting by Kenneth H.Williams and layout and design by W. Stephen Hill.

I also thank Studies in Intelligencefor permission to reprint the map of Tay Ninh from my2007 article.

vii

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

10/85

viii

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

11/85

Introduction

During the latter stages of the Vietnam War, small teams of dedicated and courageous Viet-namese special police,led by American military and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) personnel,fought a largely unsung war against the political leadership of the Communist insurgency. These

special police units were called Provincial Reconnaissance Units (PRUs), and they conductedsome of the most dangerous and difficult operations of the Vietnam War. Because these unitswere created, trained, equipped, and managed by the CIA, they worked in secret, a status thatoften led to myths and falsehoods about their activities. So pervasive are these myths and false-hoods that many historians often take them at face value without subjecting them to the samescrutiny as other historical aspects of theVietnamWar. This lack of understanding is further com-plicated because of the political divisiveness within the United States surrounding the VietnamWar, which led some opponents of U.S. involvement in that war to accept the most perniciousand false claims made against the entire pacification effort conducted by theAmerican and SouthVietnamese governments.

The passage of time and the work of some historians have helped to lift the shroud of secrecyaround the PRU and their battle against the Viet Cong.1 This book relates the story of how asmall group of U.S. Marines assigned to this program contributed to the programs success andto identify, using official records, personal interviews, and other unclassified sources the factorsthat contributed to that success.2 In so doing, I hope to inform the reader about why the PRUProgram was so successful in destroying the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI) despite many obsta-cles placed in its way by both the South Vietnamese and United States governments.

1

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

12/85

2

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

13/85

The Beginning

The Vietnam War was really two wars. Onewas the purely military war pursued by theNorth VietnameseArmy (NVA) against the mili-tary forces of the government of South Vietnam

(GVN) and the United States of America. Theother war was the insurgency waged by theVietCong political apparatus, an extension of theLao Dong Party in SouthVietnam,using local po-litical cadre and guerrillas. These two warswere part of an overall strategy of the NorthVietnamese Lao Dong Party to overthrow theGVN and unite all of Indochina, including Laosand Cambodia, under their control. This dual-track strategy by the North Vietnamese Com-munists modulated between an emphasis onclassic Maoist revolutionary war from 1956 to

1968 to a predominantly conventional war strat-egy from 1968 until the fall of Saigon in 1975.

The scope of this work does not allow for ananalysis of the dual-track strategic approach bythe North Vietnamese,but an understanding ofit is necessary for the reader to comprehendhow both sides fought the war. I leave it to thereader to refer to several excellent books on thissubject, such as Mark Moyars Triumph For-

saken, Lewis Sorleys A Better War, and HarrySummerss On Strategy, for analyses of how thisstrategy was applied during the war. The au-

thors 1988 Marine Corps Gazettearticle mayalso prove helpful.3

This work examines one aspect of the coun-terinsurgency war waged in South Vietnamagainst the Communist political leadership(hereafter referred to as the Viet Cong Infra-structure, or VCI) of that insurgency. It dealswith the primary instrument used by the U.S.Central IntelligenceAgency (CIA) to attack anddefeat theVCIthe Provincial ReconnaissanceUnit (PRU) Program.

Rudy Enders, the legendary chief of opera-tions for the CIA and one of the CIAs most orig-inal and effective organizers of paramilitaryoperations, explains below the origins of thePhoenix program in SouthVietnam and the rolethe PRUs played in the early years of its exis-tence. We pick up his story, in his own words,in 1966:

As Agency-supported programs matured,

the volume of intelligence at province level

became overwhelming. Some of it was tacti-

cal, but most pertained to the VCI. As one

would expect, the collector seldom shared ex-

ploitable intelligence with anyone. With spies

everywhere, who could be trusted? Why

should you pass hot information and let oth-

ers take credit for the operation? This could

be said of the National Police, Special

Branch, Rural Development Cadre, PRU, Mil-

itary Security Service, and Sector and Sub-

sector G-2s. In late 1966, they were all

running operations against theVCI, but there

was little coordination or cooperation. Be-

sides, delays in reaching province often ren-

dered information totally useless. Obviously,

something had to be done. The answer was

to design a mechanism to ensure coopera-

tion amongst all existing South Vietnamese

organizations operating against the VCI, and

that this be done at the district as well as the

province levels.

The CIAs Region One ROIC [Regional Of-

ficer in Charge] and his deputy grabbed the

bull by the horns. They decided to run a pilot

program in Quang Nam Provinces five dis-

tricts, starting with Dien Ban District. Visits

to these districts revealed few had 1:50,000

scale maps of their area, a war room, or anyfiles on VCI cadre. It was shocking. Most dis-

trict compounds had barely enough room for

the subsector staff and advisors. Accordingly,

the ROIC asked General [Lewis W.] Walt, the

commander of the Marines in I Corps, for

supplies to build five A-frame-type wooden

District Intelligence and Operation Coordi-

nating Centers (DIOCC). The centers would

be staffed by representatives from the CIAs

Census Grievance, PRU, Rural Development,

and Police Special Branch, along with the

South Vietnamese National Police and Mili-tary Security Service. They would be run by

the district chiefs S-2 and advised by an

American officer. The ROIC explained his ini-

tiative to John Hart, the CIAs Saigon station

chief at the time, and he used the term Intel-

ligence Coordination and Exploitation

(ICEX) as a way to describe the concept.

3

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

14/85

CIA felt ICEX was too much of a mouthfuland began looking for a symbolic alternative

by holding a region-wide contest to find a

new name for the program. The word was

passed to all I Corps POICs, and the RDC/P

(Rural Development Cadre/Programs) offi-

cer in Quang Ngai suggested Phuong Hoang,

Vietnamese for Phoenix, the mythical bird

that emerges from ashes. He won the contest,

and that is how the Phoenix program got its

name.

Phoenix was nothing more than a coordi-

nation and exploitation program directed

against terrorists and those supporting ter-

rorists. Organizations which came under the

Phoenix umbrella were already working

against the VCI. The only difference involved

sitting down at the table to coordinate and

exploit relevant, usable intelligence. It was

not some devious, nefarious CIA plot to as-

sassinate unarmed civilians. Those who

risked their lives going after armed terrorists

were not murderers. They were legitimate

military, paramilitary, and lawful police

forces facing terrorists, spies, and nonuni-

formed armed insurgents. Blaming Phoenix

for VCI deaths is like calling the FBI murder-

ers because armed terrorists preferred to

fight rather than surrender to lawful au-

thority. . . .

After we established the DIOCCs in I Corps,

the Phoenix program began to take on a life

of its own. The clandestine VCI became our

top priority. As long as it existed, pacification

was impossible. VC terror tactics were far

more effective in winning over the popula-

tion than any hearts and minds program.ICEX/Phoenix soon came under the micro-

scope of the Saigon Station staff and was

eventually scrutinized by the ambassador

and RobertBlowtorchKomer. It didnt take

long for Komer to seize upon Phoenix as a

way to make his mark in Vietnam. He had

President [Lyndon B.] Johnsons ear and this

made him politically powerful. Anyone

standing in his way would be run over with

a bulldozer.

If anyone could move the program for-

ward, it was this overbearing, arrogant, mis-sion-driven former CIA analyst. He acted as

a ramrod to implement a rifle shot rather

than ashotgunapproach to the VCI. As the

number-three man in Saigon, he vetoed var-

ious concept papers until a missions and

functionspaper finally appeared before him,

which he accepted.Anything else, he said,

would not be understood by the military.

Although Komer would be the Phoenix

Czar, he needed someone to actually run

the program. Here he fingered CIAs Evan

Parker Jr. of the Parker Pen Company. He

couldnt have made a better choice. Evan

Parker was a first-generation paramilitary

officer, having served with OSS Detachment

101 during World War II as a liaison officer

with Merrills Marauders and the British. He

was a GS-16 at the time, considered highly

4

Photo courtesy of CWO-4 Ronald J. Lauzon

Provincial Reconnaissance Unit operators in Thua

Thien Province in 1967. In areas contested or con-

trolled by the Vietnamese Communists, they would

go on operations dressed to blend in with the Viet

Cong (VC) or North Vietnamese Army (NVA). The

weapon is a Communist bloc AK-47.

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

15/85

intelligent, soft-spoken, well organized, enor-

mously respected, and extremely capable. He

also came from my parent Special Opera-

tions Division at CIA headquarters and later

became its chief, an organization I would

later head.

Essentially, those in Saigon institutional-

ized what we were already doing in I Corps.

By the summer of 1967, MACV agreed to as-

sign military intelligence officers to the

DIOCCs and PIOCCs throughout the country.

The name change to Phoenix (except in I

Corps) was in transition; thus, all the early

program guidance written by Parkers staff

was circulated as ICEX memoranda. All of

this meant nothing to us in I Corps except

added focus and high-level attention to what

we were doing. Indeed, many of the paperscirculated were simply upgraded versions of

what we already had drafted to explain ICEX

to Saigon.4

As Enders stated, the Phoenix program wasan effort to unify the disparate counterinsur-gency programs of both the United States andthe GVN so a more effective approach couldbe developed. This widely misunderstood pro-gram was a bureaucratic consolidation of thevarious ongoing intelligence-gathering effortsbeing employed in South Vietnam to fight the

Communist political infrastructure. Becausethe Phoenix program included several CIA-sponsored activities, such as the PRUs, it wasgiven an aura of secrecy that only served toarouse suspicion among many observers andlater among some scholars that the programsomehow involved illegal or criminalactiv-ities.5 In reality, the Phoenix program soughtto organize the fight against the VCI in a moresystematic and effective manner by requiringthe various GVN andAmerican agencies to co-operate and coordinate on a countrywide

level.

The efficacy of this approach was not loston the Communists, who recognized and ac-knowledged the serious threat Phoenix posedto their plans to subvert the GVN. In fact,thereis no more cogent proof of the fear thatPhoenix instilled in the Communists than the

comments of several North Vietnamese Com-munists who verified the programs effective-ness after winning the war. Perhaps the mosttelling of these are credited to Mai Chi Tho,who controlled the most famousViet Cong spyof the war, Pham Xuan An, a strategicallyplaced journalist in the Timemagazine officein Saigon. He identified Ans most valuablecontribution over nearly 25 years of spyingfor the NorthVietnamese aseverything on thepacification program . . . so we could developan anti plan to defeat them. . . . I consider thisto be the most important because of its strate-gic scale.6

Despite having the complete American andSouthVietnamese pacification plans,the Com-munists never were able to defeat the GVN

pacification program and, indeed, by early1969,the Communists realized that their planfor a general uprising using local Viet Congunits in South Vietnam was doomed to failureand that a purely military solution involvingCommunist forces from North Vietnam invad-ing South Vietnam was the proper strategy topursue. Internal Communist documents andinformation provided by CIA spies within theVCI confirmed that the VCI and their VC guer-rilla forces were largely defeated by early 1970leaving little option for the northern Commu-nists but to pursue a conventional militarystrategy. For an insight into this changed strat-egy from the enemys side, see Truong NhuTangs Viet Cong Memoir, which details theenemys analysis of the military and politicalsituation in South Vietnam during the crucialyear of 1970.

To understand the PRU Program and how itwas used to attack the VCI, it is helpful to un-derstand how it fit into the overall Phoenixprogram, in theory and practice. Before 1967,the PRU teams were under the control of CIA

officers in many ofVietnams 44 provinces,butthey had no real national-level coordinationmechanism. It was in 1967 that the PRU finallybecame a national program under CIA officerEvan Parker and was given its national-levelmission of defeating the political infrastructureof the Viet Cong.7 The ICEX Program evolvedinto the Phoenix program, but the PRU mis-

5

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

16/85

sion remained the same despite this organiza-tional change.

The Phoenix program as it emerged at theend of 1967 had organizational structures atevery level of administration in SouthVietnam.

At the national level, the Phoenix Committeewas chaired by the minister of interior, withthe director general of the National Police asthe vice chairman. Other members of the na-tional-level Phoenix Committee were the min-ister of defense, the J-2 and J-3 of the JointGeneral Staff,and representatives from the Na-tional Police Field Force (NPFF), the PoliceSpecial Branch (PSB), the Revolutionary De-velopment (RD) Ministry, and the Chieu HoiMinistry.

At the national level, one of the key CIA as-

sistants to the CIAs chief of station on the PRUProgram was the legendary Tucker Gougle-mann, a former Marine who was severelywounded during the battle for Guadalcanal.He was medically discharged from the MarineCorps after World War II and joined the CIA.The author had several conversations with Mr.Gouglemann in the Duc Hotel in Saigon in1969 and found him to be a highly intelligentand engaging man who could best be de-scribed as a brilliant and profane curmudgeonwho possessed an intense love for his job and

the Vietnamese. He also had an almost patho-logical hatred of bureaucracy and bureaucrats,whom he felt had little understanding of Viet-nam or how the war should be fought. Sadly,Gouglemann was captured in Saigon after theCommunist victory in 1975 and died under-going interrogation by the North Vietnamese.His body was released to the American gov-ernment two years after his capture andshowed clear signs of torture.8

The senior U.S. Marine officer assigned to

the PRU was then-Lieutenant Colonel TerenceM.Allen, a combat veteran of the Korean andVietnam wars who spent nearly three years inVietnam running the Department of Defense(DoD) side of the PRU program. He was tire-less in his efforts to mold the PRU into an ef-fective counter-VCI organization, a task thatwas often complicated and frustrated by what

he described as the obstruction of the U.S.State Department and the nave and false re-porting of U.S.journalists who had no valid un-derstanding of the PRU.9 Major,later Colonel,Nguyen Van Lang was the senior Vietnameseassigned to the PRU headquarters in Saigon.Later, Major Lang became the director of thePRU when control of the PRU passed from theCIA to the South Vietnamese National Police.From 1968 until 1970, Colonel Allens job in-volved providing advice and assistance toMajor Lang on the national administration ofthe program.

At the regional level, the Phoenix Commit-tee was chaired by the regions military com-mander, and the deputy chair was the regionsNational Police commander. The remainder of

the committee was made up of representativesfrom the same ministries found on the nationalcommittee.

The provincial Phoenix Committee differedfrom the national and regional Phoenix com-mittees in one very significant way. The na-tional and regional Phoenix committees werelargely administrative entities that providedguidance and advice to the seniorVietnamesepolitical leaders and set counterinsurgencypolicy. The provincial Phoenix committeeswere actively engaged in the collection of in-

telligence on, and the targeting of,the VCI. Theprovincial Phoenix committees were chairedby the province chief, normally an ARVNcolonel or lieutenant colonel,with the provin-cial police chief as the deputy-chairman, al-though in some provinces the cochair was theprovincial intelligence officer. Representativesof the G-2, the G-3, the Rural Development(RD) program,the Police Special Branch (PSB),Census Grievance (CG), the National PoliceField Force (NPFF),and the Chieu Hoi programmade up the rest of the committee,along with

intelligence officers from the military units inthe province. The provincial Phoenix com-mittees were required to meet at least once aweek, but they often met far more frequently,sometimes daily. They operated 24 hours aday, every day, collecting and discussing intel-ligence on the VCI, maintaining extensiverecords on the progress of the anti-VCI effort

6

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

17/85

in their province,and issuing arrest orders forVCI suspects.

Below the provincial Phoenix committeeswere the DIOCCs. These were the district-level Phoenix Committees, and they served as

the front-line units in the war on the VCI. TheDIOCC was organized along the same lines asthe Provincial Phoenix Committee, and likethe Provincial Phoenix Committee,it operated24 hours a day,seven days a week. In additionto its intelligence-gathering and VCI-targetingduties, it also provided intelligence for theAmerican and Vietnamese militar y units sta-tioned in the district. Each DIOCC had foursections: administrative, military intelligence,police intelligence, and operations. In manyDIOCCs, the PRU was represented, but nor-

mally they had no representation on theDIOCC. Instead, the PRU provided its intelli-gence input to the police intelligence repre-sentative in the DIOCC and received missionsdirectly from the district chief.10

The DIOCCs created dossiers on VCI per-sonnel and coordinated the efforts to arrest

VCI and bring them to justice. They also main-tained a list of all VCI positions in the districtand attempted to identify the individuals inthese positions. While many organizationswere given the mission of defeating the VCI,such as the National Police,the National PoliceSpecial Branch, and the armed forces of theUnited States and GVN, the principal actionarm of the Phoenix committees was the CIA-organized, -funded, and -controlled PRU.

In theory, the DIOCC system provided theinfrastructure needed to collect intelligenceon the VCI and to coordinate operationsagainst it. In practice, the DIOCC system didnot always work as it was intended. Accord-ing to the U.S. Marine PRU advisors inter-viewed by the author, the DIOCC system

worked very well in the provinces where therepresentatives of the Vietnamese and Ameri-can agencies on the various regional, provin-cial, and district Phoenix committees workedwell together and cooperated in the genera-tion of operational leads.

However, several of the Marine PRU advi-

7

Chart re-created from Andrad,Ashes to Ashes, p.291

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

18/85

sors interviewed for this paper stated that thesystem in their province did not meet the stan-dards necessary to fully exploit the DIOCC sys-tem. They attributed this situation to severalfactors, but the primary one was bureaucraticjealousy on the part of the agencies repre-sented on the provincial and district-levelPhoenix committees. They also identified a re-luctance to share operational leads since theagencies involved were afraid they would notreceive the credit (and the budget allocations)they deserved if another agency acted on theintelligence they gathered. Petty personalityconflicts also militated against the smoothfunctioning of many DIOCCs. They stressedthat where the provincial and district chiefshad strong leadership skills and where Ameri-can advisors to the representatives on the

DIOCCs enjoyed the confidence and respectof theirVietnamese counterparts,the DIOCCsfunctioned effectively.

Once the Phoenix program became a na-tionwide program with an organizationalstructure that ran from Saigon to each districtin the country,the CIA soon realized it did notpossess the personnel needed to provide therequired advisors for the PRU Program. In-deed, it was having great difficulty finding ad-equate numbers of CIA case officers for other

tasks in SouthVietnam,especially case officerswith any experience in paramilitary activitiessuch as were required to advise the PRU. Sinceevery province in South Vietnam needed aPRU advisor and in some cases two, the CIAneeded at least 44 American provincial PRU ad-visors and 30 regional and Saigon-based head-quarters staff. With a very limited number ofCIA paramilitary officers available worldwide,it was readily apparent that the CIA would notbe able to provide these PRU advisors usingtheir own personnel.

This serious shortcoming needed to besolved if effective control of the PRU was tobe established and maintained by the CIA. Thesolution to this problem came in the form ofassigning U.S. military personnel to the PRUProgram using cover orders assigning them tothe Combined Studies Division (CSD) of theMilitary Assistance Command, Vietnam

(MACV). Ideally, these DoD assignees were tobe skilled in the special warfare tasks neededby a PRU advisor. With this in mind, the bulkof the PRU advisors came from the U.S.ArmysSpecial Forces, the Navys Seals, and the U.S.Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance Compa-nies.

Since it was envisioned that the PRU wouldhave to coordinate closely with and supportU.S. forces, it was decided to assign PRU advi-sors to the four military regions based uponservice affiliation. For instance,since the bulkof U.S.forces in I Corps were U.S.Marines,theCIA tried to assign Marine PRU advisors to thatmilitary region. The U.S.Army was heavily rep-resented in II Corps and III Corps, so the CIAassigned U.S. Army Special Forces and U.S.

Army Militar y Intelligence PRU advisors tothose two military regions. U.S. Navy Sealswere assigned as PRU advisors to the south-ernmost military region, IV Corps. The firstlarge contingent of U.S. military advisors wasassigned to the PRU in 1967. However, someU.S. military personnel had been assigned tothe PRU in very small numbers before 1967when the PRU Program was not organizedcountrywide. Most of these early U.S. militaryPRU advisors were assigned to I Corps.11

PRU Organization, Recruitment,Equipment, and Command and

Control

Before 1967,the PRUs existed at the provin-cial level,and less than half of the provinces inSouth Vietnam had such units. They ranged insize from 30 to 300 men, depending on thesize of the province and the need for theirservices by the provincial chiefs and the CIA.Many of the early PRU units were organizedalong strictly military lines since they wereoften employed in military operations against

main force VC units. In 1967, when Civil Op-erations and Rural Development Support(CORDS) took over operation of the PRU Pro-gram, the CIA decided to give the PRU a coun-trywide presence and a standard table oforganization for a PRU team. For reasons thatare not known, it was decided that each PRUteam would consist of 18 men broken down

8

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

19/85

into three six-man squads. The senior squadleader in each team became the team leader.The idea was to assign an 18-man PRU team toeach district so the team could react quicklyto any targets identified by the DIOCC in thatdistrict. In theory, each province would begiven enough PRU teams for one to be as-signed to each DIOCC. This new organizationwent into effect in late 1967 and was main-

tained until the PRUs were integrated into theGVN National Police in 1973. This new na-tional-level PRU organization resulted in mostdistricts receiving an 18-man PRU team,whichmeant that small provinces with only a few dis-tricts or no districts had fewer than 50 PRUmembers assigned while larger, more popu-lous provinces with many districts had asmany as 300 PRU members assigned. In total,4,000 to 6,000 Vietnamese PRU personnelwere assigned countr ywide to the programduring the years 1967 to 1975.12

A typical post-1967 provincial PRU organi-zation was the one found inTay Ninh Provincein South Vietnams III Corps. In this organiza-tion, each of the four districts in Tay NinhProvince was assigned an 18-man PRU teamand an additional 18-man team was assignedto the capital of the province as a city teamthat could mount operations in the densely

populated Tay Ninh City or be used to rein-force one or more of the district teams. A verysmall headquarters cell consisting of the SouthVietnamese PRU commander; his deputy,whowas also the leader of the Tay Ninh City PRUteam; and an operations/intelligence officerprovided the staff planning and interagencycoordination for the province. According tothe Marines assigned to the PRU, this form of

organizational structure worked well despitethe paucity of personnel assigned to staff du-ties.

The recruitment of PRU personnel variedfrom province to province. Many PRU mem-bers were formerVC or former ARVN soldiers.Some were former South Vietnamese SpecialForces soldiers or former members of a Citi-zen Irregular Defense Group (CIDG), while afew were simply local youths who did notwant to join the regular ARVN forces and pre-ferred to serve their country in their own

home province. In a few provinces, someparoled criminals were allowed to join thePRU, but the number of such people was fewand greatly reduced after 1968. Some hadstrong religious and community affiliationsthat made them natural enemies of the Com-munists, such as Catholics, Cao Dai, Hoa Hao,and Montagnard tribesmen. Most PRU mem-

9

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

20/85

bers were strongly motivated by their hatredof theVCI.13 Since there were many people inevery province who had a grudge against theVCI, there were many South Vietnamese whowere eager to join the PRU. The fact that mostPRU hated the VCI made them a very formida-ble force and one that made it very difficult forthe Communists to infiltrate or proselytize.14

According to ColonelTerence M.Allen,the sen-ior military advisor to the PRU Program inSaigon from 1968 to 1970, the most effectivePRU teams were those who were recruitedamong the Cao Dai and Catholic religious com-munities and the Montagnard tribes sincethese groups had a visceral hatred of the VietCong and a vested interest in protecting theircommunities from the ravages inflicted onthem by the VCI terrorist cells.

The Marine PRU advisors interviewed bythe author expressed confidence in the re-cruiting methods used to obtain PRU membersand felt the men assigned to their units were,on balance, extremely competent and experi-enced. However, there were some notable ex-ceptions. This was especially true in the earlyphases of the PRU program when MACV firstbegan to assign its personnel in I Corps. Thesenior CIA officer in Quang Tri Province in1967, Warren H. Milberg, explained one

provinces recruiting problem this way:Quang Tri was a relatively sparsely popu-

lated province. By mid-1967, the war was

heating up at all levels. Young men of mili-

tary age and qualification were either in the

ARVN, the CIDG, or were engaged in farming

in the districts. PRU recruitment became a

problem of demographics: there was just not

a large pool of physically and mentally qual-

ified young men to choose from. It was pretty

well known in the province what the PRU did

and what their mission was so that even

those who may have otherwise qualifiedwere too risk-averse to want to join. The peo-

ple we did manage to recruit all came with

their own set of issues. For the most part,

this was not a problem, although we did

have some exceptions here and there. In the

end, they became a great group of brave

fighters, but they were not unlike a pack of

pit bulls: training, discipline, leadership and

focus were needed all the time.15

The experience of PRU advisor SergeantRodney H. Pupuhi in 1968 illustrates the re-cruiting challenges faced by the PRU in I

Corps. When he reported to his PRU unit inHoi An, Quang Nam Province, in March 1968shortly after the Tet Offensive, he was not en-couraged by what he found. The Quang NamPRU was in the midst of being disbanded, andonly seven PRU members remained out of theoriginal pre-Tet force of more than 100 men.Like any good Marine noncommissioned offi-cer, Sergeant Pupuhi immediately took chargeof the situation, held a formation of his re-maining seven-man PRU force, made themsquad leaders,and sent them to their home vil-

lages to recruit replacements for each squad.As he put it,I gave these men strict guidelineson recruiting and a deadline of two weeks toreturn with enough recruits to fill the sevensquads. Slowly, these men came back withfamily within family recruitsthat is, broth-ers recruited other brothers and nephews re-cruited cousins until we had the necessarynumbers to fill the squads.

Pupuhi arranged with the CIA to give therecruits families advance pay and to have AirAmerica fly the recruits to Hoi An. In shortorder, Pupuhi had resurrected the Hoi An PRUwith reliable men and had embarked on a rig-orous training program to prepare his new re-cruits for their demanding and dangerousmissions. Within six weeks of his arrival in HoiAn,he had recruited,trained,and equipped hisnew unit and began conducting counter-VCIoperations.16

PRU teams were equipped with an assort-ment of uniforms, weapons, and equipment.Most PRU members dressed in the black paja-

mas worn by Vietnams peasants or tiger-striped camouflage uniforms when they wentto the field, but some units actually usedVC/NVA grey or light green uniforms whensuch uniforms gave them a tactical advantage.In garrison, most PRU members wore eithercivilian clothes or the standard PRU tiger-striped camouflage uniform. This wide variety

10

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

21/85

of uniforms made it difficult for both theenemy and friendly units to identify them.Therefore,it was essential that the U.S.PRU ad-visors coordinate closely with friendly units ifthe PRU were to operate in areas where U.S.and ARVN units were located. The Marine PRUadvisors normally wore black pajamas or tiger-

striped camouflage uniforms in the field andcivilian clothes while in garrison. Some advi-sors even wore civilian clothes on PRU opera-tions but this was rare.

Weapons consisted primarily of M-16 rif les,45-caliber pistols,M-79 grenade launchers,andM-60 machine guns. However,many PRU unitsmaintained extensive armories of captured

weapons, and they often used these in opera-tions against the VCI. The PRUs found it con-venient to equip some of their men withCommunist-made AK-47 rifles and RPGgrenade launchers, so any VCI encounteredduring an operation in enemy territory wouldinitially think they were fellow VC. This gave

the PRUs a distinct tactical advantage in anyengagement.17

This ploy of using enemy weapons becamedangerous after late 1967 when the CIA beganplanting doctored AK-47 and other enemy am-munition in enemy stockpiles. These doctoredrounds would explode when fired,causing se-rious, often fatal, wounds to those firing

11

Photo courtesy of GySgt Rodney H. Pupuhi

A mor e typical Provincial Reconnaissance Unit operation showing uniforms and equipment as worn by

the Vietnamese and Americans. This was more characteristic than the VC or NVA uniforms shown before.

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

22/85

them.18 Still, despite this serious risk, manyPRUs continued to use enemy weapons andammunition after 1967 when they thought therisk was worth it. Other weapons that wereemployed by PRU members and their advisorswere Browning 9-mm automatic pistols,38-cal-iber Colt Cobra revolvers,Browning automaticrifles (BAR), M-2 carbines, Swedish K subma-chine guns, and British Bren guns. This wideassortment of weapons posed a logistical chal-lenge to some PRU teams, but in most casesthere were never any serious shortages of am-munition. Captured enemy ammunition wasreadily available, and the CIA supply systemworked wonders in obtaining just about anyammunition required for operational use. Am-munition for the PRU was often stored inConEx boxes within the CIAembassy house

compounds or in the various PRU armoriesthroughout the provinces so it could be rap-idly issued.

For communications, the PRUs wereequipped with the PRC-25 FM radio and its an-cillary equipment. A few PRU units maintainedsome high frequency radios for long-rangecommunications, but such radios were notstandard issue, and most PRUs needed to es-tablish temporary radio relay sites on moun-taintops to support their long-range missions.

This was especially true in the mountainousareas of I Corps.The PRUs were given theirown frequencies for tactical communications.They were wary of the enemy intercepting

their radio communications, so they seldomused their radios for the transmission of oper-ational details while they were in garrison,choosing instead to use their radios sparinglyand primarily during field operations. ThePRUs had neither encrypted communicationsequipment nor code pads,so communicationssecurity was often nonexistent,ad hoc,or rudi-

mentary. One of many valuable assets anAmerican PRU advisor brought with himwhenever he accompanied a PRU team to thefield was the ability to encode communica-tions; however, the use of encoding materialswas not frequently employed during most PRUoperations,even those that were accompaniedby U.S. PRU advisors. Some PRUs did not use

radios on their operations, preferring to main-tain complete silence until the mission wascompleted.

PRU forces were equipped with groundtransport in the form of commercial light

trucks and motorcycles, which were pur-chased by the CIA. These trucks and motor-cycles were typical of the trucks andmotorcycles used by Vietnamese civilians, sotheir use did not arouse suspicion or draw un-wanted attention to them when they were em-ployed by the PRU. It also made repair of thesetransport assets easy since parts, automotivesupplies,and repairs could be readily obtainedlocally. When major repairs were needed,PRUvehicles were taken to the CIAs automotiverepair facility in Saigon.

Unfortunately, the trucks and motorcycleswere never provided in the numbers neededby the PRU. Often, only two to three truckswere given to each province, thus they had tobe shared by each district team or kept atprovince level for use as needed. Most PRUteams suffered because of the lack of organictransport. As a result,the PRUs also used pub-lic transportation,such as cyclos and buses, orprivately owned motorcycles or bicycles to in-sert themselves into operational areas.Dressed in civilian clothes and posing as civil-

ian travelers, they were able to blend in withthe locals using these modes of transportationuntil they were near their operational area andready to engage their targets.19

Although most PRU operations did not re-quire U.S. military or ARVN transportation as-sets, the PRUs did avail themselves of suchtransport when it was provided to them, usu-ally through the good offices of the Viet-namese province chief, a district U.S. militaryadvisor,or the U.S. PRU advisor. For operations

over long distances and in mountainous ter-rain, the PRUs would rely primarily on U.S.hel-icopters for insertion and extraction. Most U.S.PRU advisors felt the PRUs would have beeneven more effective had they possessed addi-tional organic transportation assets, such asthree-quarter-ton trucks and motorcycles, anda dedicated helicopter package in each mili-

12

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

23/85

tary region. The U.S. PRU advisors stated thatthey often lost valuable time trying to obtainnonorganic transportation for deep or difficultPRU operations,and these delays often had anadverse impact on the success rate of such op-erations. Since most PRU targets were fleet-ing in nature, a timely response, often within24 hours,was needed to achieve success. Thelack of organic or rapidly available transporta-tion assets often meant that the target wasgone by the time the transportation had beenarranged.

As stated earlier, the PRUs were under theoperational control of the CIA. However,under an agreement between the GVN and theCIA, the Vietnamese province chiefs weregiven some control over how and when the

PRUs could be used. In some instances, thisdual-command relationship caused friction be-tween the local CIA leadership in the provinceand the province chiefs. The relationship wascertainly a violation of the unity of commandprinciple. Theoretically, all PRU operations ina province required both the approval of theprovincial officer in charge (POIC), who wasthe senior CIA officer in the province, and theprovince chief. In many provinces, the PRUsfollowed this arrangement, but in someprovinces, the CIA disregarded it.

In the case of the author, he followed thedual command relationship procedures andencountered little problem with it in hisprovince. He had few problems obtaining dualauthorization for a mission, usually obtainingthe approval of both his POIC and provincechief in a matter of a few hours. He did this byhaving his Vietnamese PRU operations officeruse a standard-form arrest order for each VCIsuspect identified, then he would hand carrythe arrest order to the province chief after thePOIC had initialed his concurrence. In some

cases, the author was also required to obtainthe signature of the provincial judicial repre-sentative on the Provincial Intelligence Oper-ations Coordination Committee to ensure thatthe arrest order was issued properly and withthe necessary legal safeguards.20

Some PRU advisors simply obtained the per-

mission of the POIC and assumed the POICwould get the province chiefs approval. Asthe program matured,the necessity to fully co-ordinate PRU arrest orders and operationswith the province chiefs became institutional-ized. One positive aspect of this dual approvalsystem was the increased cooperation it gen-erated between the Vietnamese and Americanagencies assigned counter-VCI duties. It alsohelped to break down suspicion among theVietnamese Phoenix agencies that the CIA wasacting alone and without consideration of thesovereignty of the Vietnamese government.

The PRU command and control authorityon the Vietnamese side came down from thepresident through the minister of interior tothe province chiefs and finally down to the dis-

trict chiefs, but this was more administrativethan operational since day-to-day operations ofthe PRUs were planned and executed underthe direct supervision of the CIA. In a practi-cal sense, the CIA POICs controlled the PRUsand used theAmerican PRU advisors to ensurethe PRU teams were properly employed oncounter-VCI operations.

A great deal of authority and independenceof action was given to the PRU advisors, oftenamounting to outright autonomy. Since manyPOICs were busy with their primary duties,

not the least of which was the collection ofpolitical and strategic intelligence on theenemys Central Office South Vietnam(COSVN) and the North Vietnamese govern-ment, they simply did not have the time to mi-cromanage the PRU advisor. Also,many POICslacked military experience or their military ex-perience was dated. This meant that they didnot feel they had the technical expertise toplan and control the types of operations thePRUs were conducting and preferred to leavethe operational details to the initiative of the

American PRU advisors.

Because the PRU advisors had a great deal ofcontrol over how and when their PRU teamswere employed,the job required a level of ma-turity and sophistication not commonly foundamong the normal special operations soldier,sailor, or Marine. The American PRU advisors

13

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

24/85

were unanimous in their recommendation thatthe best men for assignment to this form ofduty should be in the age range of 25 to 30years old and should have obtained at leastthe equivalent rank of sergeant (E-5) for en-listed and first lieutenant (O-2) for officers.Ideally, they felt the enlisted advisors shouldbe the equivalent of gunnery sergeants (E-7)and the officers should be captains (0-3). Com-mand and control of PRU-type units requiredobjectivity, maturity, and sound judgmentalltraits that can only be developed with timeand experience. The American PRU advisorswere unanimous in their belief that immatu-rity and emotionalism were two of the mostdestructive and corrosive characteristics a PRUadvisor could possess and,along with a lack ofcultural sensitivity, the root causes of most se-

rious problems.

The number of U.S. military PRU advisorswas small; perhaps no more than 400 were as-signed to the program from 1967 to 1971. Ofthat number,the author has been able to iden-tify 51 Marines who served with PRUs as ad-visors. See the Appendix for a list of theseMarine PRU advisors.

The experiences of the PRU advisors variedwith their respective units and the provincesin which they served. As the Phoenix program

matured and the PRU developed into a trulynationwide organization, the Marine PRU ad-visors helped mold and shape this develop-ment. The following firsthand accounts willgive the reader an idea of how the advisory ef-fort progressed from its inception until the lastU.S.military advisors were removed.

Sergeant Paul C. Whitlock: Oneof the First and Best, 1966-1967

Sergeant Whitlocks outstanding per-

formance in Quang Tri led the CIA to

ask for more such fine men to assist the

CIAs PRU advisory effort. His input is

extremely valuable in explaining how

he easily fit in and contributed posi-

tively to Agency paramilitary field pro-

grams.

Rudy Enders 21

Paul C.Whitlock was a young staff sergeantserving as a reconnaissance team leader in the3d Force Reconnaissance Company in Octo-ber 1966 when he was called into the officeof his commanding officer, Captain KennethJordan, and told he was to report to work inQuangTri City and form a reconnaissance unitthere for special police operations. Staff Ser-geant Whitlock asked Captain Jordan why hehad been selected for this assignment,and Jor-dan simply replied,because you are a Marine.Whitlock knew better than to ask any morequestions, and besides, he trusted Jordan andknew there must be a good reason why hewanted him to go to Quang Tri City. Whitlockwas one of the first Marines assigned to thePRU Program and he remained with theQuang Tri PRU from October 1966 until May

1967. The CIA officers who knew Whitlockspoke highly of him and stated that as one ofthe first Marines assigned to the PRU in ICorps, he set the standard for every Marinewho followed.

When Whitlock reported to his CIA boss inQuangTri, he found a recently organized PRU,one that had been staffed with former mem-bers of the Counter Terrorist Team (CTT) forQuang Tri. His unit consisted of 200 men, ledby a very capable PRU chief and already con-

ducting operations against the VCI. He imme-diately struck up a strong professionalrelationship with the PRU chief, and this rela-tionship remained healthy throughout theeight months that Whitlock was the QuangTriPRU advisor. Whitlock considered the PRUchief to be a strong leader who enjoyed the re-spect of his men and the Americans whoworked with him.

Whitlock also had an excellent relationshipwith the province chief. He stated that he andthe province chiefworked well together,not-

ing that he helped out when and where hecould. It was evident from Whitlocks com-ments to the author that having both a capableand strong PRU chief and a reliable and coop-erative province chief made his job easier andhis work more effective than it would havebeen without these two key men assisting him.Whitlock also had high praise for his boss, the

14

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

25/85

POIC, Thomas D. Harlan. Harlan worked inwhat was labeled the Office of Civil Opera-tions for Quang Tri Province. According toWhitlock, Harlan helped him whenever heneeded help, provided him with many excel-lent operational leads,and backed him up100percent.

The QuangTri PRU had two types of opera-tions. They were based upon the geographyof the province. Deep missions were thosethat were conducted in the western moun-tains of the province in such areas as the BeiLonValley,Khe Sanh,and the QuangTri and BeiLon rivers. These missions were assigned bythe 3d Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF)headquarters and could best be described aslong-range reconnaissance missions since their

main purpose was to determine what the NVAunits in those areas were doing. As such,theywere not the classic counter-VCI mission nor-mally assigned to a PRU. These operationswere coordinated with III MAF by the POIC,Tom Harlan, and employed handpickedteamsof PRU members. The teams were nor-mally inserted and extracted by Marine heli-copters. Prior to insertion on these deepmissions, the PRU team, which normally con-sisted of five to seven men, was isolated andonly briefed on the location of the mission just

prior to departure. This was done to ensureoperational security. Some of thesedeepmis-sions requiredWhitlock to establish radio relaystations on prominent terrain features so theteams would have continuous FM radio con-tact with PRU headquarters.

The second type of mission the Quang TriPRU conducted was thecoastalmission. Thisentailed operating in the eastern section of theprovince in the populated coastal plain. Theseoperations involved teams of 10 to 15 men.The means of insertion and extraction varied

from Marine helicopters to commercial boatsand other forms of transportation readily avail-able. The focus of the coastal missions wasthe capture of VCI, not reconnaissance. Assuch, they were equipped, dressed,and armedfor raid operations against known or sus-pected VCI targets.

The Quang Tri PRU dressed in tiger-stripedcamouflage uniforms, black pajamas, and NVAlight green uniforms,depending on the condi-tions and the mission. The only civilian clothesthey wore were the ubiquitous black pajamasworn by peasants in the countryside. The unitemployed PRC-25 radios for communications,and they carried an assortment of weapons,which were issued depending on the mission.For instance,deep mission teams normallywere armed with M-16 rif les, while coastalmissions used M-1 and M-14 rifles and M-2 car-bines.

Whitlock described his PRU as very welltrained. This was so because Whitlock made itso. Like most PRU advisors, he spent a lot oftime in garrison training his troops. Most of

his training involved land navigation, radioprocedures, reconnaissance techniques,weapons training and small unit tactics. Hepossessed well-developed organizational skillsand was able to increase the strength of hisunit from 200 to 300 men, all while maintain-ing a professional force, well trained and wellequipped for their mission.

Whitlock identified the main strength of hisPRU as the ability to move around when andwhere others could not. . . .They knew the ter-rain and the people. The one serious problem

he had with his unit was the lack of reliabilityof some of the PRU members to carry out theirmission properly. Specifically, he often couldnot be sure they went where they were in-structed to go or carried out their mission ashe wanted them to unless he went along onthe mission. Later on, he developed a meansfor checking on their veracity when he did notaccompany them on an operation. He did thisby assigning a different insert and extractionlocation for each mission. By doing this, thePRU team had to travel from its insertion loca-

tion through the area Whitlock wanted cov-ered in order to reach its extraction location.

The best source of intelligence on the VCIin QuangTri Province was the intelligence gen-erated by the PRU using local people. TheQuang Tri PRU members had their own sys-tem for gathering intelligence, according to

15

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

26/85

Whitlock, and it proved to be accurate wheremost other sources were not. Whitlock wouldsend his PRU members and their families outinto their home villages to develop operationalleads. They were to pay attention to their sur-roundings and report back. . . . Once the PRUand their family members developed enoughinformation on the local VCI, the PRU wouldlaunch an operation. Whitlock also identifiedprisoner interrogation by the PRU as a valuablesource of exploitable intelligence.

Whitlock offered this advice for futureMarines involved in a counterinsurgency likethe one he fought in during the Vietnam War:Find an in-country leader who you can trustand communicate with effectively. Also,if youcant speak the local language, find a good in-

terpreter who will follow your instructionscompletely and will translate exactly what youhave said without embellishment. 22

CIA officer Rudy Enders,who was the chiefof operations in I Corps when Whitlock wasfirst assigned to the PRU, thought Whitlockpossessed in abundance the qualities neededfor a PRU advisor. He wrote:

There are many qualifications associated

with being an effective PRU advisor. Lets

take Whitlock as an example. First of all, he

was an experienced, brave combat leaderwho could assess the capabilities and short-

comings of the men he advised. If necessary,

he could train them in every aspect of small

unit tactics starting with basic shooting, fire

and maneuver, scouting and patrolling, map

and compass, etc....I understand he did this.

Furthermore, he singled out his PRU com-

mander, Do Bach, as a heroic, competent

warrior. To gain PRU confidence, he accom-

panied Bach on dangerous missions proving

he was willing to lay his life on the line while

fighting alongside his men. This is what lead-

ership is all about.

Secondly, Whitlock was mature. He was

not some wide-eyed kid looking for adven-

ture. Instead, he understood the seriousness

of his position and behaved accordingly. I

cant overstate the importance of this attrib-

ute. PRU advisors performed their jobs with

very little oversight and supervision. This re-

quires a high degree of self-discipline and

commitment common to most Marines.

Finally, Whitlock was aggressive. He sifted

through mountains of intelligence reports to

find the most promising. His PRUs didnt sitaround in camp waiting for things to hap-

pen, they made things happen. They sought

out the enemy, enough so that the North Viet-

namese sent a special sapper unit to destroy

the PRU camp. The point is, a single Marine,

Whitlock, with CIA help, produced an effec-

tive and aggressive South Vietnamese coun-

terinsurgency force of over 300 men. 23

Staff Sergeant Whitlock was one of the firstand best U.S. military PRU advisors and, assuch, he became a model for the advisors that

followed. His POIC,Thomas Harlan, summedup the contributions of Whitlock in a letter hewrote to the commanding general, 3d MarineDivision,on 3 April 1967 thanking the generalfor sending such a highly trained and capableNCO to the PRU Program. Harlan wrote thatWhitlock displayed unique dedication, imagi-nation, and knowledge of his job. . . . [T]hePRUs under his guidance have distinguishedthemselves in long range reconnaissance pa-trols and unconventional warfare operations....[H]is methods are being adapted throughout

I Corps with all Provincial ReconnaissanceUnits being patterned after the one in QuangTri Province.

Whitlock retired from the Marine Corps asa gunnery sergeant in 1974 and then workedfour years with a high school Junior ROTC pro-gram before embarking on a 20-year career asa project manager for a major commercial con-tracting firm.

Sergeant Ronald J. Lauzon:Hue City, 1967

Sergeant Ronald J. (Ron) Lauzon had 12years of militar y experiencesix with the AirForce and six with the Marineswhen he wasassigned to the PRU on 8 March 1967. His as-signment took him to Hue City in Thua ThienProvince, and he remained with the PRU inHue City until he was reassigned to the Marine

16

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

27/85

Corps on 8 October 1967. He described thetime he spent as a PRU advisor as a great ex-

perience for an E-5/E-6 during the peak of theprogram, and one he considered the most re-warding of his Marine Corps career. He retiredfrom the Marine Corps as a chief warrant offi-cer (CWO-4). Lauzon provided the followingselected comments in a paper he submitted tothe author:

I relieved Sergeant Robert B. Bright III as

the PRU advisor for Thua Thien Province. He

had done an outstanding job of organizing,

training, equipping, and establishing coordi-

nation for the unit. I inherited a PRU unitof 137 soldiers, but I paired it down to 117,

and I lost seven killed in combat during the

seven months I was their advisor.

I did not have much bush time with the

unit;most of the100 or so operations I spon-

sored were small-unit actions aimed at gain-

ing or supporting intelligence requested by

the Regional Officer in Charge (ROIC) and,

as such, participation on them was restricted

to indigenous personnel. On most of our op-erations, a Caucasian would not have fit in,

and the CIA was paranoid about having

someone captured by the enemy who pos-

sessed internal knowledge of how the CIA op-

erated.

I did go on major military operations

which were requested by MACV, USMC, or

ARVN units, but these operations were all ul-

timate disasters for the PRU since they were

employed as regular ground forces, and they

were not trained or equipped for such em-ployment. Many times these large-scale mis-

sions were misrepresented to CORDS as

missions appropriate for the PRU, but in

every case they turned into standard mili-

tary type operations against main force VC

or NVA units.

I principally served out of Hue City and

17

Photo courtesy of CWO-4 Ronald J. Lauzon

Sergeant Ronald J. Lauzon on operations with the Thua Thein Provincial Reconnaissance Unit in 1967.

Marine advisors wore utility, tiger-stripe, or even black pajama uniforms while in the field. Note the

lack of distinguishing rank or other insignia.

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

28/85

stayed in the PRU compound, which was

Madame Nhus summer home.* This com-

pound sat on the northwest corner of the

Hue perimeter overlooking the Royal Tombs.

My area of operations was the entire

province with the exception of Hue City. The

city was solely reserved for the CORDS intel-

ligence section, which had a number of

USMC counterintelligence personnel as-

signed to it. They worked out of the National

Police Intelligence Center, and they relied

heavily on the provinces Police Special

Branch (PSB), which gathered most of its in-

telligence from the provinces interrogation

center (PIC).

I did not live in an embassy house, like

many other PRU advisors. Instead, I lived in

a leased house in southern Hue across froma large Roman Catholic cathedral close to the

Phu Can Canal along Nguyen Hue Street.

This house was where my replacement was

killed and where Ray Lau spent a couple of

days in a pigsty hiding from the VC during

the Tet Offensive when the enemy controlled

the city. I rotated where I slept almost nightly

during my PRU tour, spending some nights

at my house, some at the PRU barracks, some

at Ray Laus, some at the POICs house, and

some at other trusted locations. We were

often on alert for an attack, and we kept

arms and ammunition stored in our house

in case we came under attack.

PRU operations varied from province to

province based upon the enemy situation in

each province and the priorities of the CIA

and the province chiefs. In our case, the POIC

and his assistant strictly wanted the PRU to

generate intelligence and not lose any assets.

There was no doubt in anyones mind that

assassinations were strictly forbidden. This

was stressed by both Colonel Redel,24 who

briefed me in Saigon during my indoctrina-tion, and by my training instructors at the

CIA PRU training base at Vung Tau in III

Corps. My PRU teams were strictly focused

on obtaining intelligence about the VCI in

my province and ensuring this intelligence

was put to good use by the various Viet-

namese and American units in the province.

Since I had access to all the intelligence

resources in I Corps, I could pick up the lat-est reports from the MACV compound, the

Special Forces SOG Headquarters, the 3d Ma-

rine Division G-2, the 8th Radio Relay Unit

(RRU), the Army Side Looking Radar and In-

frared Assessments, and the PIC. I would

read through these reports each night look-

ing for any information about the latest

movements of the National Liberation Front

(NLF) committee members. This included

the VC paymasters, recruiters, party organiz-

ers, armed propaganda teams, and assassi-

nation squads. Once I picked a couple oftargets, I would go to the PRU compound

early in the morning and brief the PRU Com-

mander, Mr. Mau. We would agree on one or

two missions and assign the missions to the

platoon leader on duty, who would select the

men, uniforms, and equipment for the mis-

sions. We had two 30-man rifle platoons; a

30-man weapons platoon equipped with

60mm mortars, RPGs, and crew-served ma-

chine guns; and a headquarters section,

which included intelligence, logistics, armory,

and first-aid personnel.Once the teams were identified for the mis-

sion, they were put into isolation. The PRU

intelligence section would brief them on the

mission and any pertinent information they

had on the target(s), the supply section

would issue them their special equipment

(cameras, binoculars, sensors, radios, etc.),

and the armory would issue them their am-

munition and special weapons (sniper rifles,

claymore mines, satchel charges, pistols, etc.).

The majority of the 117 PRU I ultimately

ended up with were holdovers from the pre-

vious Counter Terrorist Team (CTT) program

in the province. We also had 13 active PRU

intelligence agents in the field. We had very

little turnover, and we were very selective in

whom we chose to join our ranks. A few of

our men were former VC, and some were for-

18

*Madame Nhu was the flamboyant wife of Ngo Dinh Nhu, the

younger brother and chief advisor of Ngo Dinh Diem, who was

president of SouthVietnam until he and his brother were assas-

sinated in 1963.

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

29/85

mer ARVN Rangers and Marines who had

completed their military service but wanted

to join the PRU in their home province. All of

my PRU were local people, and they came

from all eight districts, which meant they

had firsthand knowledge of the terrain and

people where they were operating. Most had

served in the military, eitherVC or ARVN, and

they had been trained at the PRU training

center in Vung Tau and at the Reconnais-

sance Indoctrination Program (RIP) school

at the 1st Marine Division at Da Nang. They

were, in my opinion, well trained and highly

experienced soldiers. I liked the PRU I

worked with and had complete confidence in

the team leaders and the PRU Commander,

Mr. Mau.

All operations in the province were cen-trally planned and controlled out of the PRU

compound in Hue City. To my knowledge, we

did not have active DIOCCs in the eight dis-

tricts in our province and, if we did, I had no

contact with them. To be honest, I only

trusted our own intelligence system, which

was operated by the RD/PRU/CG/CI intelli-

gence center in Hue City.

The operational PRU teams were usually

small, four or five men, with one of the men

familiar with the area of operations and the

people living there. They would dress eitherin civilian clothes or VC uniforms and be

equipped with AK-47 rifles, French pistols, M-

1 carbines, and hand grenades. They would

be inserted late in the day but before curfew

at a neutral point as close to the target area

as possible, either by public transportation

or taxicab. Sometimes they went by bicycle

or used U.S. Navy swift boats for insertion.

We often used U.S. Marine Combined Action

Platoon (CAP) compounds in the country-

side to launch operations, and we considered

these CAP areas ideal for the insertion of ourteams since they could provide coordination

with higher headquarters in the 3d Marine

Division and a safe haven once an operation

was completed.

After a team was inserted, I went to the

MACV compound and reported the opera-

tional plan. I reported the operation after in-

sertion because I did not want any enemy

agents in the MACV compound to reveal the

operation to the NLF.

While I was a PRU advisor, I read literally

hundreds of intelligence reports from the U.S.and South Vietnamese military, and not a

single one was either timely or totally accu-

rate. The military intelligence reports were

written with specific times and dates with

specific map coordinates and numbers, but I

found out from dozens of interrogations that

the VCI did not read or use map coordi-

natesthey just used place names such as

Cam Lo Bridge or Phouc LyVillageand they

measured time by after a specific event,

soon, pretty soon, or now. The unit descrip-

tions used in the military reports meantnothing to me since aVC squadcould num-

ber between 1 and 50 men and a VC com-

pany could number between a dozen and

several hundred men.

We mounted over 100 operations during

my tour with the PRU, and 11 of these were

19

Sergeant Lauzon in garrison with a member of the

Thua Thein Provincial Reconnaissance Unit in

1967. In these circumstances, civilian clothes were

usally worn.Photo courtesy of CWO-4 Ronald J. Lauzon

-

8/7/2019 Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese Provencial Reconnaissance Units 1966-1970

30/85

successful in capturing or killing VCI. There

were only two sources for these 11 successful

missions: the PRUs organic intelligence sys-

tem and Ray Laus RD Census Grievance el-

ement, which gathered information from the

RD teams travels in the province. We never