FINAL TECHNICAL PAPER-CHRIS KIPTOO - MEFMImefmi.org/mefmifellows/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/...4.3...

Transcript of FINAL TECHNICAL PAPER-CHRIS KIPTOO - MEFMImefmi.org/mefmifellows/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/...4.3...

i

FINAL DRAFT

FINANCIAL PROGRAMMING AND POLICY: THE CASE OF KENYA

By

Christopher K. Kiptoo

(MEFMI Candidate Fellow)

Supervisor

Dr. Anna Lennblad

A Technical Paper Submitted to the Macroeconomic and Financial Sector Management Institute of Eastern and Southern Africa (MEFMI) in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements

of the MEFMI Fellowship Development Program

OCTOBER 2006

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A number of people and institutions have helped me in one-way or another in the course of undertaking this technical paper. First, I would like to express my gratitude and thanks to my supervisor to Dr. Anna Lennblad for her technical guidance and constructive contribution and encouragement right from the beginning to the finalisation of this paper.

Second, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to MEFMI for admitting me to the Fellowship Program and Funding all the activities under the Customized Training Plan that included the production of this technical paper. Third, I thank the management of the Central Bank of Kenya for having allowed me to pursue the program to it successful completion. Fourth, I owe a lot of thanks to a number of staff members of the Economics Department of the Central Bank of Kenya who were very cooperative in providing the data and other relevant information used in this paper.

Finally, the completion of this study could not have been a success without the help and support of my dear wife Priscilla and my children Brian, Melvin and Mona. Notwithstanding all these support from various people and institutions, I take full responsibility for the views expressed in this paper together with any errors that may be found in it.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS iii

ABSTRACT vi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS viii

LIST OF FIGURES xii

LIST OF TABLES xiii

LIST OF BOXES xiv

1.0 BACKROUND OF THE KENYAN ECONOMY 1

1.1 Historical Background 1

1.2 Kenya’s Economic Structure 2

1.2.1 The Domestic Economy 2

1.2.2 The External Sector 3

1.3 Overview of Economic Developments in Kenya: 1963-2005 6

1.3.1 The 1963-1972 Period - A Decade of Economic Expansion 7

1.3.2 The 1973-82 Period – A Decade of Uneven Economic Growth and High Inflation 8

1.3.3 The 1983-1992 Period – A Decade of Rising Inflation and Declining Growth 9

1.3.4 The 1993-2005 Period –Another Era of Mixed Economic Performance 11

1.4 Conclusion 13

2.0 THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS OF FINANCIAL PROGRAMMING 15

2.1. Introduction 15

2.2 Theoretical Foundations 15

2.3 Evolution in the Design of Financial Programs 18

3.0 CONSISTENCY CHECKS OF MACROECONOMIC ACCOUNT LINKS 20

3.1 Consistency Checks and Derivations 20

3.1.1 Inter-Account Consistency Checks and Derivations 20

iv

3.1.2 Data Consistency Checks Within Accounts 57

3.1.2.1 Data Consistency Checks Within the National Accounts 57

3.1.2.2 Data Consistency Checks Within the Balance of Payments 58

3.1.2.3 Data Consistency Checks Within the Statement of government Operations 58

3.2.1.4 Data Consistency checks within the Depository Corporations Survey 59

3.2 Discussions of Results of the Consistency Checks 61

3.2.1 Discussions of Results of the Inter-Account Consistency Checks 61

3.2.2 Discussions of Results from the Flow of Funds 66

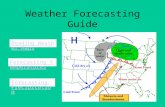

4.0 BEHAVIORAL RELATIONSHIPS FOR FORECASTING 76

4.1 The Basic Framework 76

4.2 Steps for Forecasting in Financial Programming 77

4.3 Forecasting Individual Accounts 81

4.3.1 Forecasting National Accounts: Output, Expenditure and Prices 81

4.3.2 Procedure Used in Forecasting Kenya’s Fiscal Accounts 97

4.3.3 Forecasting the Balance of payments 101

4.3.4 Forecasting Monetary Aggregates 110

4.4 Discussions of Results Obtained from Baseline Forecasting 117

5.0 SUMMARRY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.........................................121

5.1 Summary 121

5.2 Conclusions 122

5.3 Recommendations 124

REFERENCE ................................................................................................................................127

APPENDICES ...............................................................................................................................131

Appendix 1: The Results of Inter-Account Consistency Checks (in absolute terms) 131

Appendix 2: Sequence of Kenya’s National accounts (Kshs Million) 133

v

Appendix 3: Kenya’s Statement of Government Operations (in Kshs million) 137

Appendix 4: Regression Results of Exports Supply Function 139

Appendix 5: Regression Results of Imports Demand Function 144

Appendix 6: Kenya’s Balance of Payments (Kshs Million) 149

Appendix 7: Depository Corporations Survey (In Millions Kshs) 152

Appendix 8: Regression Results of Money Demand Function 154

Appendix 9: Selected Historical and Forecasted Economic Indicators for Kenya (2001-2008) 160

vi

ABSTRACT

The objective of this technical paper was to develop a framework that integrates all the four macroeconomic accounts, with internal consistency checks based on the financial programming framework. To achieve this objective, a number of data consistency checks were constructed within the financial programming framework (FPF) and the economic implications for each of them given. The manner in which the links in the consistency checks came about was derived statistically. The same framework was used to develop a forecasting scenario. The FPF was therefore used in this paper as a general approach to inform and tie together the various sectors in a consistent manner, while incorporating the Kenyan-specific factors. In this way, not only did financial programming serve as an ex ante consistency check on important macroeconomic aggregates but also provided an ex post monitoring tool.

The results of the consistency checks undertaken in chapter three revealed that virtually all the inter-account consistency checks, which were 41, in total failed to hold. To be more specific, all the ten inter-account consistency checks between the national accounts and balance of payments failed to reveal consistency except in the case of exports of services. Similarly, all the eight inter-account consistency checks between the statement of government operations and balance of payments failed to hold. In the same vein, all the three inter-account consistency checks between the statement of government operations and the depository corporations survey failed to reveal consistent results. Finally, all the thirteen inter-account consistency checks between the deposit corporations survey and the balance of payments did not reveal consistent results except in the case of monetary Gold. The results from the use of flow of funds, which was used an ultimate consistency check also produced results that were mixed. While all vertical consistency checks in the flow of funds failed, some horizontal checks failed to hold.

Based on these results, the paper concluded that there is still a lot of work to be done in Kenya to render the data from different sources consistent. In this respect, the paper made a number of recommendations. Among them was that the relevant institutions should comprehensively examine each specific item in all of the four macroeconomic accounts with a view to making sure that the compilers of such data capture all transactions by all institutional sectors as required.

The financial programming exercise carried out in chapter four involved making projections of developments in the Kenyan economy for the period 2006-08 based on the assumption that existing policies remain unchanged. The results of this baseline scenario provided a benchmark for assessing the impact of the policy package included in a program scenario. Its principal aim was to show whether existing problems were likely to remain broadly constant, to be resolved without explicit intervention by the authorities, or to worsen over time. The conclusion drawn from these

vii

results was that unless an active program is put in place for Kenya, the country’s economic situation, though impressive from the domestic front, may be undermined by the developments in the external sector and to a small extent the fiscal front.

The paper therefore recommended that an active program should be put in place to address the external sector as well as the fiscal problems that are likely to worsen over time in Kenya. The paper also recommended that the program should address the country’s fiscal problems that also seem to likely to worsen overtime if the current existing fiscal policies remain unchanged. The objective of the program should therefore be to achieve sustainable current account balance, non-inflationary growth as well as fiscal discipline.

viii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AGOA African Growth and Opportunities Act

AML Anti-Money Laundering

BB Bonds and Bills

BoP Balance of Payments

CBK Central Bank of Kenya

CBS Central Bank Survey

CE Compensation of Employees

CEg Compensation of Employees Payable by Government

CFKg Consumption of Fixed Capital by government

CFT Combating Financing of Terrorism

COMESA Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

CurAcBal Current Account Balance

Dg Government Deposits

DCS Depository Corporations Survey

DI Disposable Income

DIg Disposable Income of Government

EAC East African Community

EPSR Economic and Public Sector Reform

ESAF Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility

EU European Union

FAcb Foreign Assets held by the Commercial Banks

FAma Foreign Assets held by the Monetary Authority

FE Foreign Exchange

FEma Foreign Exchange by Monetary Authority

FC Final Consumption

ix

FCg Final Consumption by Government

FinAcBal Financial Account Balance

FinAcBalg Final Account Balance of Government

FLcb Foreign Liabilities held by the Commercial Banks

FLma Foreign Liabilities held by the Commercial Banks

FPF Financial Programming Framework

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GFKF Gross Fixed Capital Formation

GFKFg Gross Fixed Capital Formation of Government

GKF Gross Capital Formation

GNI Gross National Income

GNDI Gross National Disposable Income

G Government

IC Intermediate Consumption

ICg Intermediate Consumption by Government

IDA International Development Association

IMF International Monetary Fund

KA Capital Assets

KAcBal Capital Account Balance

KEMSA Kenya Medical Supplies Agency

KenGen Kenya Electricity Generating Company

KPLC Kenya Power and Lighting Company

Lg Loans and Advances to Government

M Imports of Goods and Services

MEFMI Macroeconomic and Financial Sector Management Institute of Eastern and Southern Africa

MG Monetary Gold

MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology

NA National Accounts

x

nADA Net Additions to Deposits abroad vis-a-vis Non-Residents

nANPNFA Net Acquisition of Non-Produced, Non-Financial Assets

nCurTr Net Current Transfers from Non-Residents

nBrg Net Borrowing vis-a-vis Non-Residents by Government

NBER National Bureau of Economic Research

nCTr Net Current Transfers from Abroad

nCTrg Net Current Transfers vis-à-vis Non-Residents by Government

NG Non-Government

nKTr Net Capital Grants vis-a-vis Non-Residents

nKTr g Net Capital Grants vis-a-vis Non-Residents by Government

nPIg Net Property Income vis-avis Non-Residents by Government

nNPNFAg Disposal/Acquisition on Non-Produced Non-Financial Asset by Government

nRFSg Net Receipts of Foreign Securities vis-a-vis Non-Residents by Government

NFAma Net Foreign Assets of Monetary Authority

NFAcb Net Foreign Assets of Commercial Banks

nI Net Income from Abroad

NLg Net Lending of Government

ODC Other Depository Corporations Survey

OP Output

OPg Output by Government

OS Operating Surplus

OSgg Gross Operating Surplus of Government

OSng Net Operating Surplus of Government

OTPg Other Taxes on Production Payable by Government

PRGF Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility

RA Reserve Assets

RPF Reserve Position in Fund

S Savings

Sg Savings by Government

xi

SB Social Benefits

SC Social Contributions

SCGSg Sales of Current Goods and Services by Government

SDR Special Drawing Right

SGO Statement of Government Operations

TIW Taxes on Income and Wealth

TMRP Tourism Marketing Recovery Programme

TP Taxes on Products

TPI Taxes on Production and Imports

TTF Tourism Trust Fund

VA Value Added

VAgg Gross Value Added by Government

VAng

Net Value Added by Government

X Exports of Goods and Services

∆ Change

∆Inv Net changes in inventories,

% Percent

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

Name of Chart Page

Chart 1.1: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1967-72 Period (%) 4

Chart 1.2: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1973-83 Period (%) 4

Chart 1.3: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1984-93 Period (%) 4

Chart 1.4: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1994-2005 Period (%) 4

Chart 1.5: Composition of Kenya's Imports During 1967-72 (%) 5

Chart 1.6: Composition of Kenya's Imports During 1973-83 (%) 5

Chart 1.7: Composition of Kenya's Imports During 1984-84 (%) 6

Chart 1.8: Composition of Kenya's Imports During 1994-2005 (%) 6

Chart 1.9: Kenya’s Real GDP Growth Rates During 1963-2004 Period (%) 7

Chart 1.10: Kenya’s Inflation Rates During 1963-2004 Period (%) 8

Chart 4.1: Inflation Rates By Region (%) 95

xiii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1: Kenya's Composition of GDP by Origin at Current Prices, 1963-2003 (Percent) ........................2

Table 3.1: Inter-Account Consistency Checks: National Accounts (Na) And Statement Of Government Operations ...........................................................................................................................25

Table 3.2: Inter-Account Consistency Checks: National Accounts (NA) Versus Balance of Payments and Balance of Payments (BOP)..................................................................................................33

Table 3.3: Inter-Account Consistency Checks: Statement of Government Operations (SOG) and Balance of payments (SGO)...................................................................................................................40

Table 3.4: Inter-Account Consistency Checks: Statement of Government Operations (SGO) and the Depository Corporations Survey (DCS) .................................................................................46

Table 3.5: Inter-Account Consistency Checks: Deposit Corporations Survey (DCS) and (Balance of Payments)............................................................................................................................49

Table 3.6: The Results of Inter-Account Consistency Checks ..................................................................62

Table 3.7: Kenya’s Flow of Funds for 2004 (in Kenya shillings, Millions) ...............................................69

Table 4.1: Forecasting of Activities for the Period 2006-08 .....................................................................83

Table 4.2: Gross Domestic Product by Activity (Percentage Change).......................................................88

Table 4.3: Proxy Bases for Forecasting Revenues ...................................................................................97

Table 4.4: Transactions Affecting Kenya’s Net Worth (% GDP)..............................................................98

Table 4.5: Proxy Bases for Forecasting Expenses .................................................................................100

Table 4.6: Forecasting of Balance of Payments Items............................................................................102

Table 4.7: Forecasting of Monetary Aggregates in the Depository Corporation Survey ...........................115

Table 4.8: Selected Historical and Forecasted Economic Indicators for Kenya (2001-2008) ....................118

xiv

LIST OF BOXES

Box Name Page

Box 4.1: The Export Supply Function 105

Box 4.2: Import Demand Function 106

Box 4.3: Money Demand Function for Kenya 115

1

1.0 BACKROUND OF THE KENYAN ECONOMY

1.1 Historical Background

Kenya is a former British colony that gained independence in 1963 and became a republic in 1964. It has an area of 582,646 sq. km and a population of about 32 million, up from the 28.7 million and 15.3 million recorded in the 1999 and 1979 national census, respectively. Kenya’s population is distributed in a very uneven way throughout the country, with the majority dwelling in the Highlands, where the climate is mild. The population density hardly reaches 2 inhabitants per sq km in the arid and semiarid areas found in the north and northeast parts of the country, whereas in the rich and fertile western the rate rises to 120 inhabitants per sq km. Urban population is nearly 25% of the total and is concentrated in a few large cities, mainly in Nairobi, Mombasa, Nakuru, Eldoret and Kisumu.

Since the late 1970s, Kenya’s social indicators have been mixed in terms of performance. Over this period, for instance, contraceptive prevalence has doubled, and the total fertility rate has fallen from 8.0 children per woman to about half that number. Current estimates on fertility range from 3.1 to 5 births per woman, making Kenya among the countries with the lowest birth rate in Subsaharan Africa. Life expectancy, on the other hand, has fallen to about 48.3. Estimates place the death rate at 16.3 deaths per 1,000 people and the infant mortality rate at about 79 per 1,000 live births. The age structure of the population is very young, with 42 percent of the population under age 15, and only 2.9 percent being 65 or older. The median age is estimated to be about 18.6 years. Kenya’ literacy rate is estimated at 80 percent, with the female rate being about 10 points lower than that of the male. HIV/AIDS is one of the threats to economic recovery. It is estimated that about 4 million people (equivalent to about 12.5 percent of the population) is infected with HIV, with about 80-90% of this figure estimated to be in the 15-49 age group.

From independence in 1963 until the elections held in December 2002, Kenya had two Presidents, Jomo Kenyatta (who ruled for 15 years from 1963 to 1978) and Daniel Arap Moi (who ruled for 24 years from 1979 to 2002). Both were from the party Kenya Africa National Union (KANU), which ruled Kenya until when it lost to National Alliance Rainbow Coalition (NARC) in the elections, held in December 2002, with Mwai Kibaki becoming Kenya's third President. Kenya’s legislature is a single chamber National Assembly with 224 members, 210 of whom are directly elected every five years in single-seat constituencies; 12 members are nominated by parties on a pro rata basis; and 2 ex-officio members (the Speaker and the Attorney General). The president who is also directly elected for five years holds executive power.

2

1.2 Kenya’s Economic Structure

1.2.1 The Domestic Economy

Kenya's economy can be divided into three sectors, namely: the primary sector, the secondary sector and the tertiary sector. The primary sector is composed of agriculture, forestry, mining and quarrying activities. Kenya’s economy has traditionally been based on the performance of the primary sector where the agriculture activity plays a prominent role. The primary sector’s contribution to GDP has, however, been on a declining trend over the decades as shown in Table 1.1 below. In particular, Agriculture’s weight in GDP decreased from 34.9% in the first decade of independence (1963-72) to 31.3% and 24.8% in the third (1983-92) and fourth (1993-2003) decade, respectively. Its dominant role in Kenya’s economy is still supported by the fact that about 75-80% of the employed population works in agriculture. 50% of income earnings from exports also come from this activity.. Mining and quarrying, which is the other major component of Kenya’s primary sector, has also declined as a proportion of GDP from 0.4% in the first decade of independence (1963-72) to 0.2% in the fourth decade (1993-2003).

Like the primary sector, Kenya’s secondary sector has similarly declined in performance as a share of the country’s GDP. This development has been mainly in the utilities and construction sub-sectors as the manufacturing activity has grown, albeit marginally (Table 1.1). The share of manufacturing activity in the country’s GDP has grown slowly to account for 11.5% in the period 1993-2003 compared to 11.1% in the first decade (1963-72). It employs 10% of the population. The major industrial plants are located around the big cities, mainly Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu. The main industries are food (crop processing and canning), beverages, tobacco, chemicals, petroleum derivatives, metals, textiles, leather, rubber, construction materials (cement, clay, glass), motorcar assembly and pharmaceutical products. Other consumer goods that are manufactured are plastics, furniture, batteries and soap.

Kenya’s tertiary sector has registered significant growth as a percent of GDP since independence. During the first decade of independence, the share of the tertiary sector as percent of GDP was 45.1%. The share, however, rose such that by the fourth decade covering 1993-2003, it stood at 57.8% of the country’s GDP. The improvement in the country’s tertiary sector as percent of GDP was mainly in the following activities: trade, restaurants, hotels as well as services from financial institutions as shown in Table 1.1 below.

Table 1.1: Kenya's Composition of GDP by Origin at Current Prices, 1963-2003 (Percent)

Origin 1963-72 1973-82 1983-92 1993-2003

Primary sector 35.3 34.5 31.6 25.0

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing 34.9 34.3 31.3 24.8

3

Table 1.1: Kenya's Composition of GDP by Origin at Current Prices, 1963-2003 (Percent)

Origin 1963-72 1973-82 1983-92 1993-2003

Mining and quarrying 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.2

Secondary sector 19.6 20.6 18.8 17.2

Manufacturing 11.1 12.6 11.7 11.5

Construction 4.8 6.0 5.6 4.5

Utilities 3.6 2.0 1.5 1.2

Tertiary sector 45.1 44.8 49.6 57.8

Trade, restaurants, and hotels 9.8 11.0 11.5 20.5

Transport, storage, and communications 7.6 5.7 6.7 7.7

Financial institutions 3.6 5.7 7.8 11.0

Ownership of dwellings 5.8 6.4 8.1 5.6

Other services 18.3 16.1 15.6 13.0

GDP at factor cost 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Sources: Government of Kenya, Statistical Abstract and Economic Survey, various issues

1.2.2 The External Sector

During the first two decades of independence, Kenya's exports were limited to a narrow product range, mainly coffee, tea, and pyrethrum (see Charts 1.1 and 1.2). This situation left the country highly vulnerable to external vagaries such as changes in world prices. Over the last two decades, however, the government's efforts to diversify the export base resulted in the growth of non-traditional exports, especially horticulture commodities (e.g. cut flowers, fresh fruits and vegetables) as shown in Charts 1.3 and 1.4 below.

Coffee exports, which use to be the leading foreign exchange earner in the first decade, declined such that by the fourth decade it had been relegated very far away from the top list of Kenya’s foreign exchange earners, only contributing about 9%. The latest data (for year 2005) shows that Kenya’s leading exports are tea and horticulture that accounted for 17.4% and 13.4% of total exports, respectively. Coffee accounts for 4% of total exports. Kenya’s other significant exports are petroleum products, fish, cement, pyrethrum, and sisal. The main destination countries for Kenya’s merchandise exports in 2005 were: Uganda (17.5%), United Kingdom (9.6%), Tanzania (8.2%), the Netherlands (7.5%), Pakistan (5.8%), the Democratic Republic of Congo (4.0%), Egypt (3.6%), and Rwanda (3.0%). Total exports to African countries accounted for 49.3% of Kenya’s total merchandise exports.

4

Chart 1.1: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1967-72 Period (%)

Unroasted Coffee21%

Tea13%

Petroleum products

16%

Pyrethrum3%

Horticulture5%

Cement3%

Soda Ash2%

other37%

Chart 1.2: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1973-83 Period (%)

Unroasted Coffee

28%

Tea14%

Petroleum

products25%

Pyrethrum

2%

Horticulture7%

Cement3%

Soda Ash1%

other20%

Chart 1.3: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1984-93 Period (%)

Unroasted

Coffee20%

Tea24%

Petroleum

products13%

Pyrethrum

2%

Horticulture8%

Cement1%

Soda Ash2%

other30%

Chart 1.4: Composition of Kenya's Exports During 1994-2005 Period (%)

Unroasted Coffee

9%

Tea24%

Petroleum products

6%

Pyrethrum1%

Horticulture3%

Cement1%

Soda Ash1%

other55%

Source: Own Calculations from Data obtained from Statistical Abstracts and Economic Surveys

5

Kenya’s imports are primarily industrial inputs including crude materials, petroleum and refined petroleum products, edible oils and fats, agricultural and transport machinery and manufactured goods. As indicated in charts 1.5, 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8, the composition of Kenya’s imports has changed over the last decade. Significant changes have particularly occurred in the imports of manufactured goods, with the decline being attributed to the growth of the manufacturing sector that led to import substitution of the manufactured products. The major sources of these imports are mainly Asia and Europe. In 2005, Kenya’s main sources of imports where: United Arab Emirates (13.4 percent), United Kingdom (12.1 percent), United States of America (9.1 percent), South Africa (9.1 percent), Saudi Arabia (5.9 percent), India (5.2 percent), Japan (5.0 percent), China (4.3 percent), Germany (3.4 percent) and France (3.0 percent) in 2005.

Chart 1.5: Kenya's Composition of Imports During 1967-73 (%)

Food & live animals

7%

Beverages & Tobacco

1%

Crude Materials

3%

Mineral Fuels10%

Chemicals10%

Manufactured goods

24%

Machinery & Transport

eqp.32%

Others13%

Chart 1.6: Kenya's Composition of Imports During 1974-83 (%)

Food & live animals

4%

Bev. & Tobacco

1%

Crude Materials

2%

Mineral Fuels30%

Chemicals11%

Manufactures15%

Mach. & Transport

eqp.29%

Others8%

6

Chart 1.7: Kenya's Composition of Imports During 1984-93 (%)

Food & live

animals6%

Beverages &

Tobacco0%

Crude Material

s3%Mineral

Fuels21%

Chemicals

17%Manufac

tured goods14%

Machinery &

Transport eqp.29%

Others10%

Chart 1.8: Kenya's Composition of Imports During 1994-2005 (%)

Food & live

animals8%

Beverages &

Tobacco1%

Crude Materials

3%Mineral Fuels20%

Chemicals

15%

Manufactured

goods14%

Machinery &

Transport eqp.26%

Others13%

Source: Own Calculations from Data obtained from Statistical Abstracts and Economic Surveys

1.3 Overview of Economic Developments in Kenya: 1963-2005

Kenya’s post-independence economic history can be divided into four periods, each constituting a decade. The first two periods, namely 1963-72 and 1973-82 is characterized by strong economic performance and huge gains in social outcomes. The other two periods (1983-92 and 1993-2004) is typified by slow or negative growth, mounting macroeconomic imbalances and significant losses in social welfare, notably rising poverty and falling life expectancy. Failures to sustain economic reforms and increased role of politics over policy are at the heart of this structural break.

7

1.3.1 The 1963-1972 Period - A Decade of Economic Expansion

The first decade of Kenya’s independence covering the period 1963-72 was one of economic transformation. During this decade, Kenya not only experienced rapid expansion of smallholder cultivation but also introduction of high-value crops including tea and coffee and adoption of high-yielding maize varieties and the development of dairy farming, all of which led to rapid increases in agricultural output. The country also experienced rapid increases in industrial output, mainly due to import substitution activities. An expanding export services to neighboring countries as well as emerging tourism sector led to improved balance of payments position in Kenya. The country, for instance, had a balance of payments situation in which both the overall and basic balances were in surplus. This was also reflected in the continuous increase in the Central Bank reserve holdings from US$ 51.5 million in 1966 to US$ 205.2 million in 1970. The surplus was accompanied by a high real growth rate of 6.5% per year over the period 1963 to 1972 (Chart 1.9).

Chart 1.9: Kenya' GDP Growth Rate rates (1963-2004)

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

1963

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

Year

Per

cent

(%)

REAL GDP growth rate (1982 prices) REAL GDP growth rate (2001 prices)

Such a rapid rate of economic growth meant that real per capita incomes had increased significantly since independence, despite the country having had one of the highest rates of population growth in the world. This success was also attributed to a number of factors including the existence of a politically stable atmosphere necessary for a high level of private investment. Kenya's savings performance over the period under review was good. Gross domestic savings, as a proportion of GDP, averaged around 19-20 percent in most years between 1964 and 1972. As a result of the successful fiscal policies of government, public

First Decade

Second Decade

Third Decade

Fourth Decade

8

sector savings rose to over 23 percent of total savings by 1971. Additionally, the rate of inflation remained low, averaging 2.8 per cent per annum (Chart 1.10).

1.3.2 The 1973-82 Period – A Decade of Uneven Economic Growth and High Inflation

Overall, growth throughout this decade was uneven, fluctuating between 1.5% in 1974 and 8.6% in 1977, with the latter principally resulting from sharp improvement in the external; terms of trade. On average, growth during this decade averaged 4.5% (Chart 1.9). Like many Sub-Saharan African countries, Kenya was beset with unprecedented succession of external shocks, such as changes in the level and variability of terms of trade compounded by increases in oil prices, rising and variable international interest rates and sharp changes in the availability of foreign financing by the end of 1973. The economy was particularly hurt severely by the world oil price shock of 1973 and two poor harvests in 1974-75 period.

These problems were compounded by the inefficiencies and distortions brought about by the pursuit of inward development strategies such as the controls in the country’s financial system that became apparent and were exacerbated by the emergence of severe macroeconomic difficulties during this period. In the domain of international trade and payments, these problems showed up in the form of growing balance of payments deficits1, which became increasingly difficult to finance. In the internal economy, the same problem emerged as an increasing government budget deficit. The financing of the budget deficit was in many cases

1 The country’s terms of trade deteriorated further owing to adverse world conditions while the volume of exports

declined, thus causing deterioration in Bop. Other episodes of BOP crises experienced in Kenya were in 1975 and 1979.

Chart 1.10: Infation (annual average)

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

1963

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

Year

Per

cent

(%)

Infation

9

inflationary. For instance, inflation in 1975 accelerated to an annual average of 15.5 per cent compared with 4 per cent in 1974.

During the next four years up to 1982, balance of payments position worsened recording large deficits while inflation accelerated back to double-digit figures (Chart 1.10). GDP growth rate also dropped to low levels, averaging 3.2 per cent per annum – a rather relatively low level compared to earlier years. The lower growth was attributed to, among other factors; the effects of the second oil price shock experienced in 1979 and a military coup attempt in August 1982. Also contributing to declining economic growth was the stance of fiscal policy in 1979-82 that proved to be highly expansionary, mainly due to a sharp increase in Government expenditure. In fiscal years 1979-82, for instance, the budget deficit averaged about 8 per cent of GDP per annum and was principally financed by borrowing from the banking system. These large budget deficits and the consequent large borrowing from the banking system marked the beginning of a challenging period for the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) in managing monetary policy. While the use of monetary policy before 1979 yielded reasonable results, monetary policy in the period after 1979 proved less effective largely because of unsupportive fiscal policy. The attempts in 1980/81 to liberalise imports, devalue the shilling exchange rate and raise the interest rates did not help much in improving the economic growth rate.

It is important to note that during this decade, the Executive Board of the IMF approved an extended arrangement and three standby arrangements for Kenya. The extended arrangement was approved in July 1975 while the three standby arrangements were approved in August 1979, October 1980 and January 1982, respectively. Each of these programs was, however, interrupted, primarily because the performance criterion on net credit to government was not observed. This is reflected in the uneven economic growth that was observed during this decade.

1.3.3 The 1983-1992 Period – A Decade of Rising Inflation and Declining Growth

Real GDP growth during this decade was mixed but on average was 4.0%, a level relatively lower than that registered in the previous two decades. A severe drought experienced in 1983-84 adversely affected growth and forced government to resort to food imports to avert famine. Thus, economic performance in the first three years of the decade under review remained below 3% in spite of the Executive Board of the IMF having approved two standby arrangements for Kenya in March 1983 and in February 1985. Each of these programs was also interrupted following the failure by the government of Kenya to observe the performance criterion, particularly on net credit to government as required. The continued decline in economic performance culminated in the drawing up of Sessional Paper No. 1 of 1986 on Economic Management for Renewed Growth by the end of the first half of 1980s. This policy document, which was supported by the IMF and the World Bank, set to renew the economic recovery and

10

growth through a process of economic liberalisation. It set off the process of undertaking far reaching institutional and structural reforms in the economy. The change from inward looking import substitution policy regime to outward oriented strategy led to higher earnings of foreign exchange and in turn helped to reduce the balance of payments deficits.

Owing to the undertaking of these reforms as spelled out in the Sessional Paper No. 1 of 1986, real GDP growth rebounded; averaging 5.6% per annum during 1986-90 in spite of continued deterioration in terms of trade. Kenya, however, experienced sharply worsened economic conditions from late 1991 to early 1993. Economic growth decelerated from 4.4% in 1990 to 0.4 percent in 1992 (Chart 1.9), inflation accelerated from 20% in 1990 to 34% in 1992 (Chart 1.10) and external payments arrears emerged for the first time in Kenya’s history. Several factors accounted for this crisis. First, the economy was faced with a series of exogenous shocks that included drought owing to irregular rainfalls, a large influx of refuges from neighbouring countries faced with internal civil strive and unfavourable export prices in world commodity markets. Second, protracted and unsettled social and political conditions in the period leading up to the first multiparty elections in December 1992 impacted on economic policy making. Third, balance of payments assistance from bilateral donors was suspended in late 1991, reflecting donor’s concerns over weak economic policy implementation as well as the lack of progress in the introduction of multiparty democracy. Fourth, several major economic policy reversals occurred, notably in liberalization of the external sector and the maize market and this undermined the public’s confidence in the government’s economic management.

Widespread mismanagement of the financial system also contributed to the economic crisis in the early 1990s. The mismanagement involved access to central bank credit by four commercial banks through irregular means. This included access to large overdrafts with CBK as well as access to the export pre-shipment finance facility for financing of fictitious gold exports (they were not reflected in the customs statistics). The commercial banks also persistently failed to meet prudential requirements in addition to the statutory cash ratio. Thus, excessive liquidity expansion, which mainly went to finance the presidential, parliamentary and civic elections held in December 1992, became a major destabilizing force in the economy. These problems compounded the perennial difficulties relating to the central government budget and public enterprise performance. Serious problems were therefore encountered over the period not only in the implementation of macroeconomic policies, particularly monetary and to a lesser extent fiscal polices but also structural reforms particularly those pertaining to trade and exchange rate regimes as well as maize marketing. Weak export performance together with the cessation of balance of payments support brought about severe foreign exchange shortages and a major compression in imports also compounded the problem.

11

1.3.4 The 1993-2005 Period –Another Era of Mixed Economic Performance

As a result of further economic reforms undertaken in early 1990s, Kenya’s economy moved onto a road to recovery. GDP grew by about 3 percent in 1994 and by an estimated 5 percent in 1995 up from 0.4 percent in 1992 and 0.1 percent in 1993. Fiscal deficit was sharply reduced from over 11 percent of GDP in 1992/93 to 2.6 percent in 1994/95. Expansion in money supply, though still high, was also reduced substantially. Inflation was also reduced substantially - annual inflation declined steadily from a peak of 62 percent in January 1994 to 6.9 percent in December 1995. However, after a small surplus in 1993, the current account balance (excluding official transfers) deteriorated to a deficit of 0.4 percent of GDP in 1994, and further to an estimated 4.2 percent in 1995. Kenya's real GDP grew at 5% in 1995. The budget deficit on commitment basis and excluding grants was reduced from 2.3% of GDP in 1994/95 to 1.4% of GDP in 1995/96 fiscal year, much lower than the programmed target of 1.9% of GDP. Although the conduct of monetary policy was complicated by large financial inflows and upward pressure on the exchange rate, success was achieved in moderating the growth in broad money (M3) and private sector credit significantly by end 1995. With the removal of all controls on trade, exchange rate and liberalization of the current account, the terms of trade increased to 100 percent in 1994. This was a marked improvement from the previous downward trend.

In order to consolidate further the gains made in the previous three years, the Kenya Government, in conjunction with the IMF and World Bank, developed a Policy Framework Paper in February 1996 that spelled out economic reform program to be implemented within the next three years. In support of the program, the Executive Board of the IMF approved a three-year loan under the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) amounting to SDR 149.55 (equivalent to 75 percent of Kenya’s quota then) on April 26, 1996. The program aimed at accelerating real GDP growth to 5 percent; maintaining inflation at 5 percent and sharply reducing the external current account deficit.

Despite the significant policy shifts supported by the IMF and World Bank and accompanying improved economic conditions witnessed in the first half of 1990s, economic trends in the second half of 1990s were disappointing, with GDP growth declining and falling substantially below the population growth rate, estimated at 2.4%. Real GDP grew by an estimated 4.2 percent in 1996, somewhat lower than programmed target of 5%. GDP growth rates assumed declining trends from 2.3% in 1997, 1.8% in 1998 and 1.4% in 1999 and drifting to negative 0.3% in 2000 -the lowest level since independence as shown in chart 1.9. The weak performance of the economy was attributed to a combination of factors including governance and management problems in the agricultural co-operative institutions that adversely affected production of most cash crops; poor transport and communications infrastructure devastated by

12

the El Nino rains of 1997 and 1998 and which continued to impose heavy costs on businesses; reduced effective demand particularly for manufactures; and reduced domestic investment and savings due to declining investor confidence due to, among other factors, the withholding of donor funding, following the lapse2 in July 1997of the IMF’s ESAF supported programme.

In September 1998, the World Bank’s Board endorsed a new three-year country assistance programme for Kenya. Subsequently, the Kenya government undertook a series of governance and public sector reforms that paved the way for a resumption of a “base case” lending from the World Bank, through International Development Association (IDA). Under this program, the Bank’s Board approved an Economic and Public Sector Reform (EPSR) in three tranches for a total of US$ 150 million on August 1, 2000. This was immediately followed by an approval of three-year arrangement under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) by the IMF Executive Board on August 4, 2000 amounting to Special Drawing Rights (SDR) 150 million. On October 18, 2000, the Board also approved a modification of the program that significantly increased the fiscal deficit allowable to take account of the effects of drought and augmentation of access of SDR 40 million. In spite of this support from Brettonwood Institutions, economic activity in 2000 remained weak. The severe drought experienced during this year caused real GDP to contract by 0.3 percent. Kenya, however, managed to achieve some modest economic growth in the period 2001-05 despite the difficult external environment it continued to face.

Responding to the various policy measures undertaken by the new Government since taking over power in January 2003, the economy recovered, with real GDP expanding by 2.8% in 2003 from 1.1 percent in 2002, 1.2 percent in 2001 and negative 0.2 percent in 2000 (chart 1.9). The main sources of growth were agriculture and the manufacturing activities. The agricultural activity is estimated to have grown by 1.3% in 2003 compared with 0.9% growth in 2002, with coffee and horticulture recording strong growth in output. Growth in the manufacturing sector was estimated at 1.2% in 2003 compared with 1.0% in 2002. The manufacturing sector continued to be supported by tax incentives introduced over the previous two financial years as well as the more liberal trade policies that increased access to external markets particularly in East African Community (EAC), Common Market for Eastern and southern Africa

2 The IMF suspended the three-year loan for Kenya under the enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF)

signed on April 26, 1996 for an amount equivalent to SDR 149.55 million (about $216 million). This loan was meant to support the Government's economic reform program for 1996-98, which was built on the policy framework paper published by the Kenyan Authorities on February 16, 1996. The first annual loan in an amount equivalent to SDR 49.85 million (about $72 million) was disbursed in two equal semi-annual instalments, the first of which was made available on May 15, 1996. The World Bank also put a $90-million structural adjustment credit on hold.

13

(COMESA), and United States through African Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA). Major services such as transport, telecommunications, tourism and financial services also registered notable improvements in 2003.

The economy grew by 4.3% in 2004, up from 2.8% in 2003 in spite of the high cost of production inherent in steady rise in wages, crude oil prices and structural bottlenecks associated with inadequate infrastructure (Chart 1.9). The growth was mainly reflected in tourism and transport and communications sectors, which grew by 15.1% and 9.7%, respectively. Manufacturing, trade, and building and construction activities, also performed well, having expanded by 4.1%, 9.5% and 3.5% respectively in 2004. Growth in the export sector, mainly in horticulture (13.2%) and tea (10.5%), as well as significant expansion of credit to productive sectors at affordable interest rates in the local money market, and faster growth in the world economy also supported economic recovery during the year. Appropriate fiscal and monetary policies pursued resulted in a conducive macroeconomic environment for investment, particularly affordable interest rates and a stable exchange rate.

Real GDP growth rose for the third consecutive year in 2005, to reach an estimated 5.8 percent. Strong performance in the tourism, construction and telecommunications sectors stimulated activity, which was underpinned by robust private sector credit growth stemming from the implementation of modest reforms and the lagged effect of a sharp fall in interest rates in 2003. A jump in imports stemming from higher oil prices and aircraft purchases caused the current account deficit to leap to 8.3 percent of GDP in 2005, from 2.3 percent of GDP one year earlier. Nonetheless, large short-term financial inflows generated a balance of payments surplus and foreign exchange reserves rose by 18 percent over 2005 to end the year at $1.8 billion (equivalent to three months of imports of goods and non-factor services).

1.4 Conclusion

Based on the above discussions, it is clear that Kenya has over the last four decades faced macroeconomic disequilibria. Like most African countries, Kenya had to undertake macroeconomic stabilization and structural adjustment based on agreed IMF-supported adjustments programs in an effort to bring about internal and external balance. While macroeconomic stability has generally been achieved in Kenya following the undertaking of these reforms, that stability has, however, been fragile particularly when viewed against the backdrop of generally low economic growth rates.

The most daunting economic challenges that the country continues to face today are the creation of enough employment opportunities to absorb the large number of new entrants into the labour market and the alleviation of poverty. More than two million Kenyans are currently unemployed and at least ten million people are living below the poverty line (defined as

14

earnings of less than US$ 1 per day). A large proportion of Kenya's population does not have access to safe water for domestic use, adequate health facilities and health provision, and minimum requirement of food and essential-non-food commodities. Above all, income inequality between the poor and the rich in our country remains high.

The challenge therefore that faces Kenya is to design a financial program that will enable the country achieve the desired growth rates of at least 7 percent per annum and hopefully overcome the problems of high poverty levels and unemployment it currently faces. Ability to undertake appropriate financial programming and policy advice is therefore critical. This technical paper develops a framework that integrates all the four accounts and with internal consistency checks. It is an attempt to develop Kenya’s own financial programming model and in this way take command of the technical analysis and thus be in a position to negotiate with the Fund in more pro-active terms. It will also lead to establishment of the foundation for a deeper commitment to prudent macroeconomic policy management in Kenya.

15

2.0 THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS OF FINANCIAL PROGRAMMING

2.1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the theoretical framework underpinning the discussions of the next two chapters of this paper, namely; chapters three and four. In summary, chapter three presents a number of data consistency checks that have been constructed within the financial programming framework and gives the economic implications for each of them. It also derives statistically how the links in the consistency checks have come about. Chapter four, on the other hand, uses the financial programming framework (FPF)3 to develop a forecasting scenario. The purpose of this chapter therefore is to provide the theoretical foundations of the FPF.

The discussions in Chapter I brought out clearly that Kenya has over the last four decades faced a number of macroeconomic disequilibria and thus had to undertake macroeconomic stabilization and structural adjustment during these periods. The adjustments were based on the agreed IMF-supported programs aimed at bringing about internal and external balance. Policy targets for these programs had to be derived from the standard financial programming framework. The following section provides the theoretical framework that underpins the FPF.

2.2 Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical foundations of financial programming are based on the model designed in 1957 by J. J. Polak4 in his article entitled: Monetary Analysis of Income Formation and Payments Problems. Cast within the framework of a small open economy with a fixed exchange rate system, the model assumes that balance of payments problems were purely a monetary phenomenon, implying that money supply was an endogenous variable influenced by surpluses and deficits in the balance of payments.

Since the 1950s, the Polak model has been the centrepiece of the analysis leading to IMF conditionality—the policy actions that a borrowing country must take to have access to IMF credit. It thus forms the cornerstone of Fund programs. In general, Fund-supported programs are packages of policy measures which, combined with approved financing, are intended to achieve certain economic objectives that include: reducing inflation, promoting growth and poverty reduction, and reducing vulnerability to future balance of payments problems or financial crises. A program is thus defined by its broad objectives, the analytical framework

3 The FPF is not a macroeconomic model per se, but rather a set of accounting identities constructed on

spreadsheets that link the accounts of the major sectors of an economy in an internally consistent manner.

4 The work of Polak (1957) were modified in the 1960s and 1970s by Walter Robichek (1967, 1971)

16

linking these objectives to policies, and the formulation and implementation of individual macroeconomic and structural policies.

The FPF attributes balance of payments (BoP) disequilibria to excessive credit expansion. The framework therefore considers domestic credit ceilings and a predetermined exchange rate as the key policy instruments to achieve the desired BoP target. The variables are autonomous changes in exports and the creation of domestic bank credit (Polak, 1957).

The model has four building blocks, two of which are behavioural in nature while the other two are accounting identities. The first is the demand-for-money function, which is behavioural in nature. In its simplest form, the model assumes that the demand for money is proportional to income. In this case, a change in a country's money supply (M) is assumed to be proportional to the change in its income (Y) by a factor k. In an equation form, this relationship is expressed as:

tdt YkM ∆=∆ ……………………………………………………………………………….(1)

Equation 1 shows that there is a constant proportional relationship between nominal income Y, and the money-stock M. The coefficient of proportionality, k, is the inverse of the velocity of circulation of money (Y/M); thus, k = M/Y. Going by the functional form of equation 1, it implies that the average and marginal income velocities are equal, and constant5. In this case therefore, any increase in nominal income will equal the increase in the money stock times the velocity of circulation of money.

The second building block is also a behavioral relationship, namely, the demand for imports (M) expressed as a function of a country's income (Y). This is expressed in an equation form as follows:

tt mYM = …………………………………………………………………………………(2)

where m is the country's marginal propensity to import. Equation 2 shows that there is a constant proportional relationship between imports at time t, and nominal income at time t via the marginal propensity to import out of income. Like equation 1, the lack of a constant in the equation implies that the average and marginal import propensities are the same. It is also assumed that 0 < m < 1 i.e. an increase in nominal income leads to a proportional increase in imports.

5 The constancy of the velocity of circulation of money is a crucial assumption in monetarist models of the

economy.

17

The third building block is an accounting identity expressing the change in the money stock as the sum of changes in its international and domestic components. This is expressed in an equation form as follows:

ttst NDCNFAM ∆+∆=∆ ……………………………………………………………….(3)

where ∆ stM is the change in the money supply, ∆ NFAt is the change in the net foreign

reserves of the banking system (expressed in domestic currency) while ∆ NDCt is the change in the domestic credit of the banking system. The monetary identity represented by equation 3 is the most important identity in FPF. This identity could apply to the central bank, in which case M is high-powered money, or it could apply to the entire banking or financial system, in which case M is broad money, implying M is derived from the deposit corporations survey (i.e. consolidated balance sheet of the banking system including the Central Bank). The identity states that the change in assets in any form (i.e., the increase in the stock of international reserves of the monetary system expressed in domestic currency, plus the increase in domestic credit) is eventually equal to the change in liabilities ( ∆ Ms,), implying increase in the nominal supply of money.

Combining equation 1 and 2 yields the equilibrium in the money market, which in equation form is represented as:

st

dt MM ∆=∆ …………………..………………………………………………………..…(4)

where dtM is the money demand at time t while s

tM∆ is the money supply also at time t. This

means at equilibrium, change in the demand for money is equal to the change in supply of money in the money market.

The final building block is another accounting identity expressing the change in foreign reserves (R) as being equal to exports (X) minus imports, plus net financial inflows of the non-bank sector (K).

tttt KMXNFA +−= …………………….………………………………………………….(5)

Equation (5) is the definitional equation underlying the balance of payments. It states that the change in net foreign assets is equal to exports of goods and services minus imports of goods and services plus net financial inflows. Both equations 3 & 5 are accounting identities that have to be satisfied over any defined time-period. The four equations (i.e. 1, 2, 3 and 5) form the basis of the Polak model, that itself is the basis of the FPF. It is clear from the four equations that the Polak model has four endogenous variables and three exogenous variables. The endogenous variables (with corresponding symbols) are (i) the stock of money (M) (ii) nominal income (Y) (iii) imports of goods & services (M) and (iv) net foreign assets (NFA). The

18

exogenous variables (with corresponding symbols) are (i) exports of goods and services (X); (ii) financial inflows (K) and (ii) net domestic credit (NDC).

From the above equations, it is clear that the FPF not only assumes a one for one relationship from the identity between the policy variable and the outcome variable but also assumes that the other variables in the identity are exogenous with respect to the policy variable. Thus, the FPF is a dynamic model as the variables in the model include macroeconomic targets. These are what the policy maker aims to achieve, such as output and inflation. It also includes policy instruments, which are the variables that the policy maker aims to change, such as money growth rates and levels of government spending, in order to attain the desired changes in the target variables. The specification of the FPF rests on both economic theory (in particular, Keynesian and Monetarist theory) and the analysis of historical data. The multiplier represents the Keynesian elements, the marginal propensity to expenditure being equal to 1 and the monetarist elements are represented by the speed of money in circulation. Data on the macroeconomic variables are interfaced with the model in order to generate statistical results that give more refined information regarding the behaviour of the economy, such that the impact of policy changes can be reliably measured.

2.3 Evolution in the Design of Financial Programs

The theoretical foundations of financial programming have remained generally unchanged since the 1970s. However, the conception and the structure of financial programs (also called adjustment programs) have gradually evolved and expanded since 1970s, partly reflecting institutional and structural changes in most developing countries that often sought support from the IMF and World Bank. Significant events that have occurred in the world economy have also necessitated the changes in the approach to program design.

While structural measures were rarely an element in Fund-supported programs until the 1980s, almost all programs included some element of structural conditionality6 by the 1990s. The expansion of structural conditionality was also reflected in increasing numbers of performance criteria, structural benchmarks, and prior actions. The increasing structural content of Fund-supported programs has, however, prompted legitimate concerns. In particular, the Fund has 6 Conditionality is the link between the approval or continuation of the Fund's financing and the implementation of

specified elements of economic policy by the country receiving this financing. It is a salient aspect of the Fund's involvement with its member countries. This link arises from the fact that the Fund's financing and policy adjustments by the country are intended to be two sides of a common response to external imbalances. Conditionality is intended to ensure that these two components are provided together. In other words, it provides safeguards to the Fund to ensure that successive tranches of financing are delivered only if key policies are on track, and assurances to the country that it will continue to receive the Fund's financing provided that it continues to implement the policies envisaged. IMF, “Conditionality in Fund Supported Programs: Policy Issues”, 2001:PP1-20

19

been criticised for overstepping its mandate and core area of expertise, using its financial leverage to promote an extensive policy agenda and short-circuiting national decision-making processes. Moreover, the expansion of conditionality has raised issues regarding its effectiveness. Arguments have been put forward that most conditionality have been too comprehensive and these have undermined the ability of most countries to not only implement the necessary reforms but also Marshall the necessary political support for a multitude of policy changes advocated in the programs. Finally, there have been concerns that overly pervasive conditionality have tended to detract countries from implementing desirable policies owing to failure by the authorities' to take ownership of the program and instead viewing them as imposed by the IMF.

Concerns have also been raised that the FPP framework has, by and large, ignored the existence of country-specific structural features and adverse external shocks. Easterly7 tested the financial programming model and reported large statistical discrepancies in the accounting identities, concluding that such identities do not make a macro model. The assumption of constant velocity failed in the data and velocity was found to be non-stationary. Easterly found the programming approach as flawed, because it does not take into account the endogeneity of virtually all the variables in each macroeconomic identity, the instability of its simple behavioural assumptions, and the large statistical discrepancies in all the identities. To address this problem, he advocated for additional structural features to describe the macro economy so as to minimize the statistical discrepancies.

Finally, it is worth noting that the mutual dependence of instruments and targets within the FPF means that the modelling process is usually iterative and often quite complex. A key concern is ensuring consistency of the macroeconomic framework and coherence of the policy stance across instruments to meet program objectives. Financial programming is used as a general approach to inform and tie together the various sectors in a consistent manner, while incorporating country-specific factors. In this fashion, not only does financial programming serve as an ex ante consistency check on important financial aggregates, it also provides an ex post monitoring tool. This is clearly seen in the next two chapters of this paper.

7 Easterly, W., “The Effect of IMF and World Bank Programs on Poverty”, 2000:P26

20

3.0 CONSISTENCY CHECKS OF MACROECONOMIC ACCOUNT LINKS

This chapter presents a number of data consistency checks that have been constructed in this technical paper. The chapter is structured in two parts. Part one contains the consistency checks and gives the economic implications for each of them. It also derives statistically how the links in the consistency checks have come about. Part two uses the Kenyan data as an example to check the efficacy of the consistency framework developed in part one of this chapter.

3.1 Consistency Checks and Derivations

This part is divided into two sections. Section one provides the inter-account consistency checks and gives the economic implications for each of them. Section two presents a number of data consistency checks that must hold within each account.

3.1.1 Inter-Account Consistency Checks and Derivations

The purpose of this section is to develop consistency checks that ensure that data are consistent within and across the accounts and as reliable as possible. This is achieved as follows: First, there is set of inter-account identities that must hold. For example, exports in the national accounts must be equal to exports in the balance of payments. Some of these are very simple, but some are slightly more complicated. For example, final consumption (FC) by government in the national accounts must equal compensation of employees (CE) plus intermediate consumption (IC) plus consumption of fixed capital (CFK) less sales of current goods and services (SCGS) in the government account. Second, there is a set of control mechanism within each account. For example disposable income (DI) by financial corporations and non-financial corporations must equal to savings (S) of each corporations.

Third, we will check for data gaps in the collection strategy. The best way to do this is to comprehensively examine each specific item in all of the accounts to investigate whether it is likely that we have captured all transactions by all sectors that might be involved in that transactions category. For example, in the balance of payments the starting point would be exports and imports. The main source of data comes from customs. But the customs data by definition does not capture smuggling and it might also not capture donor-financed imports. Furthermore, it does not capture repair of capital assets by non-residents nor does it capture repairs done by residents on capital assets by non-residents. One would therefore have to check whether the compilers of balance of payments and national accounts for that matter have made an effort to include such flows in the data.

The next item is income. In Kenya, the credit side for compensation of employees shows zero in each time period. This cannot be true given the substantial presence of international organizations mainly the United Nations and the large number of embassies in Nairobi. All of

21

these bodies employ a considerable number of Kenyan residents some of whom are professional even though most are working as non-professionals. This type of examination should be done for each item. It should be part of the financial programming exercise because the ultimate goal of financial programming is to forecast and analyse data. Unless the dataset is complete, the analysis and forecasting loose a lot in value or meaningfulness.

As final step, we will subject the whole dataset to a flow of funds, which is the ultimate data consistency check. The flow of funds is based on the following main principles: First, all credit items are treated as positive values while all debit entries are treated as negative values. In this way, consistency checks ensure that the total value of each and every account must be equal to zero. Secondly, all prorated values are checked so as to ensure that they are equal the total.

The following sections provides the list of inter-account consistency checks for the national accounts (NA), statement of government operations (SOG), balance of payments (BOP) and Depository corporations survey (DCS) followed immediately by explanations and where applicable derivations of each consistency checks. Underpinning the whole consistency checks framework is the fact that all transactions are either of a current, capital or financial nature. Additionally, the double-entry system is used to ensure that the sum of all the transactions within any account is equal zero. Thus, the sum of the current account must be equal to the sum of the negative of the capital and financial account. Similarly, the sum of the current and capital account must be equal to the negative of the financial account.

It is imperative to note that the national accounts, the balance of payments and the statement of government operations are transactions accounts while the depository corporation survey is a stock account. Transactions are defined as acts in which two units engage in an economic exchange on a voluntary basis8. Acquisitions, disposals, borrowing, wages, interest, output and consumption are examples of such transactions. Relevant transactions in national accounts, the balance of payments and the statement of government operations are; consumption of fixed capital, withdrawals from inventories and migrants’ transfers, respectively. Although most transactions take place between two units, there are situations in which a single unit acts in two different capacities. Under this circumstance, it is analytically useful to treat this act as a transaction. Since such a transaction is internal to one economic unit, it is referred to as an internal transaction9. It is also important to note that transactions are one of three flow

8 IMF, “Balance of Payments Manual”, 1993:P6

9 Ibid “Government Finance Statistics Manual”2001: PP 23-24.

22

categories. The other flow categories are; holding gains/losses10 and, other changes in volumes of assets. The two latter flow categories are recorded and organized in separate accounts.

A stock account, on the other hand, shows the value of an asset or a liability at a given point in time. Capital assets like machinery and housing as well as financial assets like loans and deposits are examples of stocks. Thus, a stock refers to a position or a value at one point in time while flow refers to an action or is an effect of an event during a time period. Given that a change between the closing balance and the opening balance is equivalent to the total flow, it is normally inappropriate to use stock accounts as source data for transaction accounts. This is because the total flow, not just the transaction is captured. This is particularly relevant for all positions in foreign exchange and for all those that are traded in a secondary market.

3.1.1.1 Inter-Account Consistency Checks: National Accounts and Statement Of Government Operations

When the statement of government operations is being compared with the national accounts, there are certain things that must be taken into account:

• The statement of government operations is consolidated as far as government transactions are concerned while the national accounts are not.

• Own-account production is reflected as capital formation both in the government account and in the national accounts. However, own-account production is also reflected as cost of production (i.e. compensation of employees plus intermediate consumption) in the national accounts but not in the statement of government operations.

• Government account in practise are compiled on cash basis while the national accounts are compiled to a very large extent on accrual basis

(a) Consolidation of Government Transactions

If statistics are done correctly, the statement of government operations should be a consolidated account. Thus, all transactions between government units are netted or eliminated. However, in the national accounts, all transactions involving two government units should be shown. A

10“Holding gains/losses (also referred to as capital gains/losses or valuation changes) are defined as a change in the monetary value of assets and liabilities in the recording period, due to fluctuations in the exchange rate and/or changes in the domestic and foreign prices of assets/liabilities. Other changes in volumes of assets on the other hand are defined as changes, which are due neither to transactions nor to unrealised holding gains/losses. Examples include writing-off bad debts, theft and, involuntary seizure of assets without compensation”. Lennblad (2005), “Stocks versus Flows and Flow Categories”

23

central government, for instance, may give a transfer to a municipality. The value of that transfer should be shown in the national accounts but not in the statement of government operations due to the fact that it is netted out in the process of consolidation. Another example is when the central government purchases a service such as electricity from a municipality. While that transaction does show in national accounts, it is reflected as zero in the statement of government operations owing to the consolidation process.

In general, therefore, one will get higher values for the gross flows in the national accounts than in the statement of government operations. This statement is mainly relevant in the use of goods and services (i.e. intermediate consumption), sales as well as transfers. It is, nevertheless, not relevant for compensation of employees, transactions with non-residents or transactions with banks. This is because the other party to the transaction, by definition, is a unit outside the government sector. This means that when data is being compared across the two sets of accounts, one should approach the relevant officers in the ministry of finance to find out if they consolidate the statement of government operations as well as relevant staff in the national statistical office to establish if they do adjustments in order to show the total value of gross flows and not only the consolidated flows. If no adjustments are made, data should be identical across the two sets of accounts. However, if adjustments are made, transfers, sales and intermediate consumption should be somewhat larger in the national accounts.

(b) Own-Account Production

In a situation where the compilation of statistics is done correctly, gross fixed capital formation recorded in the statement of government operations should be the same as that recorded in the national accounts. In this case, own-account production is reflected as capital formation both in the government account and in the national accounts. However, own-account production is reflected in compensation of employees and intermediate consumption (the sum of the two equals cost of production) in the national accounts, but not in the government account.

For instance, in the statement of government operations, an improvement on an existing capital asset or the acquisition of a new capital asset, such as a bridge or building, when done on own account, should not be recorded as the cost of production, but only as gross fixed capital formation. In the national accounts, on the other hand, all three entries should be made, namely: compensation of employees; intermediate consumption, and; gross fixed capital formation. Thus, if data compilations are done correctly, the compensation of employees and intermediate consumption (i.e. cost of production) recorded in the statement of government operations would be smaller than that recorded in the national accounts. It is therefore recommended that one should contact the ministry of finance and the national statistical office to ascertain the nature of the compilation methods. If the statistical office makes no adjustments, data should be identical. Otherwise, national accounts data should relatively be bigger.

24

(c) Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Government accounts in practise are compiled on cash basis while the other accounts are compiled to a very large extent on accrual basis. When accounts are compiled on cash basis, only transactions that give rise to a cash flow are included in the accounts. Thus, the time of recording corresponds to the time the cash payment is made or received. Accrual accounting, on the other hand, means that the timing of the entry should reflect the time of the underlying economic event or process. Accordingly, the transaction should be recorded when the economic benefit associated with an event is flowing from or to the entity.

In practise, government accounts are compiled on cash basis while the other accounts are compiled to a very large extent on accrual basis. The prevailing norm in all internationally accepted guidelines for macroeconomic accounting is that transactions should be recorded on accrual basis. Many statistical offices particularly in Africa, Middle East and other developing countries, however, often do not make an effort to make adjustments to the statement of government operations to be based on accrual accounting. Due to the failure to make these adjustments, that which is recorded in the statement of government operations is often not equal to what is recorded in the other accounts.

Some transactions could have different meaning when compiled on cash or accrual basis. For example, interest payments could have an accrued component and arrears component. If done correctly, both the accrued and the arrears components would be shown in the national accounts and the balance of payments. However, if the recording of transactions of government operations is done strictly on cash basis, neither the accrued component nor the arrears component of interest payments would be shown in the statement of government operations.

In the case of grants, the balance of payments and national accounts, if done correctly should show the total values of the grant11 including technical assistance and transfers in kind. However if the statement of government operations is done correctly on cash basis, technical assistance and transfers in kind are not shown. This is also the case for arrears in loans repayment. If done correctly, the arrears of loans repayments would be shown in the balance of payments account but would not be reflected in the statement of government operations. The same also applies for debt rescheduling and debt forgiveness. In fact, no entries are made for debt rescheduling and forgiveness in a cash account.

The financial programmer must therefore contact people responsible for compilation of balance of payments and statement of government operations and find out the methodology of

11 Grants are also called transfers in both the balance of payments and the national accounts.

25

compilation of these five transactions categories, namely: interest payments, transfers, arrears debt rescheduling and debt forgiveness. If no adjustments are made, data should be identical across the two sets of accounts. However, if adjustments are made, these transactions should be somewhat larger in the balance of payments and national accounts compared to the statement of government operations.

Table 3.1 below provides eight inter-account consistency checks between the national accounts and the statement of government operations.

Table 3.1: Inter-Account Consistency Checks: National Accounts (Na) And Statement Of Government Operations