Elizabeth Nourse, the firstlibrary.cincymuseum.org/topics/a/files/artists/red-002.pdf · national...

Transcript of Elizabeth Nourse, the firstlibrary.cincymuseum.org/topics/a/files/artists/red-002.pdf · national...

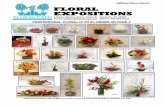

Queen City Heritage

Elizabeth Nourse, the firstAmerican woman elected amember of the New Salon, wasborn and educated in Cincin-nati but spent most of her lifein Paris. She painted her Self-portrait at the age of thirty-three

and the mirror image makesher appear to be left-handed.

Spring 1983

The rediscovery ofElizabeth Nourse

Elizabeth Nourse

Mary Alice Heekin Burke

Elizabeth Nourse, Cincinnati's most eminentwoman artist, graduated from the McMicken School ofDesign of the University of Cincinnati in 1 8 81, went to Parisin 1887 when she was twenty-eight years old and lived thereuntil her death in 19 3 8.1 During her career, she achieved allthe honors to which an expatriate artist could aspire. She wasthe first American woman elected a member of the SocfeteNationale des Beaux-Arts (hereafter, the New Salon) whenthe Salon, the annual exhibition of contemporary art heldeach in Paris, was the primary showcase for internationalartists. Acceptance by the Salon jury, which was made up ofthe most important artists of the day, gave an art work theguarantee of quality that collectors and curators required tojustify their purchases.

Nourse also won many awards in the inter-national expositions of the time, in Chicago, Nashville,Paris, St. Louis, and San Francisco. She was consistentlyinvited to show at the annual juried exhibitions that were aprominent feature of the American art scene: at the Pennsyl-vania Academy, the Carnegie Institute, the Chicago Art

Institute, the Cincinnati Art Museum, and the CorcoranGallery. As a final accolade, the French government boughther painting, Les violets clos, in 1910 for its collection ofcontemporary art at the Musee du Luxembourg to hangwith the work of such artists as Whistler, Winslow Homer,and Sargent.

Despite such recognition during the produc-tive years of her career, Elizabeth Nourse and her work weresoon largely forgotten. Only in recent years have collectorsand curators begun to demonstrate a significant interest inher work. The rediscovery culminated in the opening of amajor retrospective at the National Museum of AmericanArt in Washington, D.C., on January 13, 1983, and thesimultaneous publication of a lavish catalog raisonne bythe Smithsonian Institution. The exhibition, with the titleElizabeth Nourse, 1859-1938,, a Salon Career, displayed 104

oils, watercolors, pastels, and drawings and included por-traits of women working, mother and child scenes, land-scapes, and genre paintings.2 The catalog, with the sametitle, lists some 700 works by the expatriate artist andillustrates 300 of them. It comprises the broadest surveyof European subject matter yet recovered from an Americanartist of this period.3

1 R ,

Mary Alice Heekin Burke, adocent for the Cincinnati ArtMuseum, served as guest cur-ator for the Smithsonian Insti-tution while piecing togetherNourse's career and locatingseveral hundred paintings.

The Elizabeth Nourse Collectionat the Cincinnati HistoricalSociety contains many articlesabout Nourse which appearedin magazines as well as cata-logs and reviews of her work.

The obvious question arises—why has such adistinguished artist been forgotten? One reason is that herRealist work went out of favor after World War I, but themost important factor is that, until recently, art history andart criticism were written by men about male artists makingit extremely difficult to find substantial material on the lifeand work of women artists. Maty Cassatt, a friend of Nourse'sin Paris, was the one American woman artist of this era whobecame well publicized because she was identified with theImpressionists, all men, who had no difficulty attracting theattention of the press.

With few exceptions, the work of women art-ists has never commanded the market as has that of maleartists. They are usually considered "Sunday painters" whodo not produce a sizeable body of work, and their paintingsare found one to a collector making them difficult to evalu-ate. Moreover, they have rarely been the subject of one-person exhibitions and catalogs which would bring theirwork to public notice.

The process of rediscovering Elizabeth Noursebegan with research on her paintings at the Cincinnati ArtMuseum for entries in The Golden Age: Cincinnati 'Painters ofthe Nineteenth Century Represented in the Cincinnati ArtMuseum, a splendid catalog and exhibition organized byDenny Young, the museum's curator of painting. Themuseum files and archives provided some valuable material,but the Elizabeth Nourse Papers at the Cincinnati HistoricalSociety first revealed the quality and variety of Nourse'swork and the extent of her fame during her working career.

The Elizabeth Nourse Papers are a treasuretrove of information about the artist. They include photo-graphs of her paintings, medals she won, reviews of herwork, catalogs containing her entries, and notes by theartist's niece and donor of the collection, Melrose Pitman, asto where some of her paintings were located. In addition,there are numerous sketches, Nourse's estate inventory thatlists some seventy-four paintings returned to Cincinnati in1938, and seventy-two letters in her correspondence datedfrom 1 890 to 1919. Some of the items raised more questionsthan answers, for instance, a passport written in Russian andmarked, "Warsaw, January 24, 1889." This intriguing mate-rial led to further research in libraries to ascertain how manypaintings could be located.

The Library of Congress proved the bestresource for old catalogs of all kinds, such as the Saloncatalogs from 1888 on, or those for international exposi-tions from Copenhagen to San Francisco. In these one finds

The Nourse collection whichMelrose Pitman donated to theSociety contains sketch books,letters written by and toNourse, drawings, paintings,and numerous other items. Thesketch books and diaries pro-

vided a marvelous source fortracing her travels andresearching her painting style.

Spring 1983 Elizabeth Nourse

not only entries for Nourse paintings, but illustrations ofthem as well. Various museum libraries contain catalogs oftheir annual exhibitions, and it was a testimony to Nourse'sstature as an artist that her work was often illustrated in theseas well since only about thirty of some hundred worksshown yearly could be pictured in them. Handbooks pub-lished by museums also revealed those that owned Noursepaintings, including the Art Institute of Chicago, SmithCollege Art Museum, the Detroit Institute of Arts, theNewark Museum, the Grand Rapids Museum, the ArtMuseum of South Australia, and the Portland (Oregon) ArtMuseum.

This material together with other sources inCincinnati provided a substantial biography of Nourse'searly years, but her life in Europe was only sketchily docu-mented. Then a Nourse descendant produced a scrapbook,dated 1 880-1911, that had been maintained by the artist'sdevoted sister, Louise, who lived with her all her life. Thiswas a researcher's dream come true— in chronological orderit contained press clippings, photographs of importantpaintings that are dated and marked with the names of thebuyers, and lists of paintings entered in exhibitions. One ofthe marked paintings led to a Cincinnati collector who notonly had a complementary scrapbook, dated 1911-1932,

but had also inherited eighteen of Nourse's sketchbooks.These beautiful sketches were likewise dated and annotatedgiving a record of the artist's travels in France, Holland, Italy,Austria, Russia, Switzerland, Spain, Africa, and Alsace. Inaddition, sketches that served as the basis for paintings wereoutlined and signed, so that compositions of paintings thathave never been located can be determined.

The fascinating life and work of ElizabethNourse emerged from this wealth of material. In 1859she and her twin, Adelaide, were the last of ten childrenborn to Caleb and Elizabeth Rogers Nourse. Their parents,descendants of pioneer New England families, had marriedin Cincinnati in 1833 and shortly thereafter converted toCatholicism. Their religion became an important force intheir lives and remained a profound influence on the lives oftheir children and on Elizabeth's concerns as an artist.

Caleb Nourse was a prosperous banker whosebank failed as a result of Cincinnati's financial decline whenthe Civil War disrupted its river commerce. The threeyoungest of his children, the twins and Louise, who was sixyears older than they, grew up understanding that they mustprepare themselves to earn a living. Louise graduated fromWoodward High School and became a teacher and the twinstook courses at the School of Design which was open to allqualified residents tuition free. Elizabeth, however, undertookthe full curriculum, taking in all five years of drawing andpainting and four years training in sculpture. She also studiedwoodcarving, china painting, and engraving, and, after hergraduation in 18 81, returned to study for two years in thefirst life classes offered to women since a nude model wasavailable only for male students during her school years.

Adelaide mainly studied woodcarving in theclasses inaugurated by Benn Pitman whom she was to marryin 1882. Pitman, an Englishman and younger brother of SirIsaac Pitman, the inventor of shorthand writing, had settledin Cincinnati in 18 5 2 to estabish the Phonographic Institutefor the dissemination of the Pitman method. His avocationwas design reform and he became Cincinnati's most visibleand vocal link to the English arts and crafts movement. Tocounteract the use of shoddy, machine-made home furnish-ings, he taught his students to value simplicity and originalityin design and fine craft work. His stated aim was to teachwomen because he believed they would eventually influencepublic taste through the decoration of their own homes.

From its inception in 18 7 3, the Wood CarvingDepartment was overwhelmingly feminine in enrollmentand most of the women came from families of socialprominence.4 Pitman also provided the teacher and materials

Elizabeth Nourse took coursesin drawing, painting, and sculp-ture at the School of Designand graduated in 1881.

Both Nourse sisters, Elizabethand Adelaide, studied underBenn Pitman whom Adelaidemarried in 1882.

Queen City Heritage

Melrose Pitman gave thePortrait of Benn Pitman to theCincinnati Historical Society.The portrait is signed "To myDear Brother—Benn Pitmann— E. Nourse 1893"

Spring 1983 Elizabeth Nourse

for a class in china painting in 18 74 and many of the womenin this class went on to become decorators at the RookwoodPottery.5 Adelaide became proficient in both arts whileElizabeth was more interested in the design aspects. Themost important result for the painter of her participation inthe design reform movement was the lasting friendships sheformed among the women involved in it. Even though shelived in Paris for nearly fifty years they never forgot her—theyadmired her work, publicized it, and bought it.

Of the many women who helped the artistachieve success, however, the two most important were hersister, Louise, and her Cincinnati friend, Anna SeatonSchmidt. Louise was indispensable as her companion, house-keeper, secretary, and business manager and Anna served asher chief publicist. The latter was a successful writer andlecturer on art who wrote enthusiastic articles about Nourse'swork in International Studio, Art and Progress, Century Maga-zine, and in newspapers in Cincinnati, Boston, and Washing-ton, D.C. She frequently visited the Nourses in Paris andjoined them on their painting trips in Picardy, Brittany, Italy,and Switzerland, so that her accounts of Nourse's work arethe most personal and knowledgeable that can be found.

In 18 80 both of Nourse's parents died and thefollowing year, when she graduated from the School ofDesign, she was offered a position as teacher of drawing

there. She declined because she was determined to be aprofessional artist, and she set about earning a living in avariety of ways. She executed pen and ink drawings of localhomes, such as the Rawson and Bullock residences, illustratedmagazine articles, did mural decorations, and painted por-traits and flower paintings. Louise retired to keep house forher, and the two sisters saved their money to finance furtherstudy for Elizabeth in Paris. They were unaware that hertechnique, characterized by strong draughtmanship andmasterful handling of light and shade, was already formed sothat she would have no problem competing with the best ofthe young artists abroad.

St. ffiforgtttff Sird)e, ©alfyoun Strafje.

Nourse had not only developed her individualstyle, a realism that reinforces the subject matter, but she hadfound her themes as well. Her future interest in the peasantsubjects that were so popular among the Salon painters ofher day was simply an extension of her preoccupation withthe simple subjects she painted in the Midwest—the dailyroutine of rural folk, especially women at work, portraits ofNegro women, and country landscapes. One has to comparethe academic painting of the established artists who depictednoble themes, executed with smooth brushwork and arbi-trary color, to understand that Nourse's style represented thereaction of the young, modern artist against the oldergeneration.

Her interest in peasant themes scapes. Her Head of a Negrowas an extension of her pre-occupation with the simplesubjects she had painted in themidwest—the daily routine ofrural life, portraits of Negrowomen and girls, and land-

Gir/ done about 1882 wasgiven to the Cincinnati ArtMuseum by Harley I. Procter.

At first Nourse earned moneyby making drawings of privatehomes and illustrating booksand magazines.

In August 1887 the sisters arrived in Pariswhere they rented a studio on the Left Bank and Elizabethenrolled at the Academie Julian. After three months shewas advised that she needed no further instruction so sheset to work preparing La mere for the spring Salon. Thispainting was not only accepted by the jury but hung "onthe line," at eye level, a signal honor for an unknown artist.For all its rich, dark color harmonies and academic finish,this beautiful painting was modern for its day in its sim-plicity and realism. Nourse was able to convey an emotionalquality that is not sentimental, and, by omitting any anec-dotal details that would depict a specific mother and child,she infused it with a universal feeling, that of any woman'slove for her child.

W-vKvmk-.

This was an auspicious beginning for the youngCincinnatian in Paris, but the next important step was to sellher work. Tracing the history of La mere demonstrates howdifficult this could be. Some seven years and exposure at fiveexhibitions were required before Nourse sold it, apparentlyfor $ 300. After the Salon of 18 8 8 the painting was exhibitedin London at the Continental Gallery, shown in Liverpoolthe next year, then Glasgow, and again in her 1893 retro-spective in Cincinnati. In 1894 it was bought at an exhi-

Queen City Heritage

bition in Washington, D.C. by Parker Mann, a local artist.By 1914 it was hanging in the Princeton study of WoodrowWilson, then governor of New Jersey. It is revealing thatthe artist signed this work "E. Nourse" as she did all herearly paintings because she apparently felt that it would bemore favorably received if the public did not know shewas a woman. By 1891 she began to sign her full nameon her Salon entries and by 1904 this had become herstandard signature.

The Nourse sisters made their headquarters inParis for the next four years but they traveled widely. Elizabethtook her only trip without Louise when she spent six weekswith a friend in Russia in 1889 and that summer they wentto Picardy accompanied by Anna Schmidt. In 18 90 the threewomen traveled through Italy together for several monthsand it was in Rome that Elizabeth received an invitation tojoin the New Salon. This new exhibition group was organizedby modern French artists, such as Puvis de Chavannes andAuguste Rodin, in reaction to the conservative standards ofthe established artists who served on the jury of the OldSalon. Nourse promptly joined the rebels although she tookthe risk that the new group might fail to gain acceptance andshe would lose the opportunity to become a Salon painter.

Alice Pike Barney was one of themany interesting women whosupported Nourse. This sketchof Barney was done in Parisin 1888.

The Society's Family Group, acharcoal and watercolor doneby Nourse, illustrates her con-tinued interest in paintinginfants and mothers and children.

Spring 1983 Elizabeth Nourse

In 1888 Nourse entered La mere Gamble's collection of paintingsin the Salon of the Societe by Cincinnati artists.Nationale des Artistes Francais,Paris. Her painting was acceptedand was hung "on the line"La mere is now in Procter &

Anna returned home and the Nourses jour-neyed to Assisi where they spent six weeks. Assisi was a placeof pilgrimage for them since they had become members ofthe Third Order of St. Francis, a lay group that observes amodified version of the Franciscan rule. The primary require-ment is that members perform acts of personal charity, apledge that the Nourses took very seriously and incorporatedinto their daily lives. It resulted in their becoming deeplyinvolved in the lives of Elizabeth's models, feeding theirchildren, helping the sick and elderly in their families, andperforming innumerable personal services for them. Thisaffected the way Elizabeth saw her subjects. Because sheshared in their lives, she was able to portray rural and urban

Queen City Heritage

working women with a depth of understanding that eludedartists who knew them only as picturesque subjects.

This Italian sojourn lasted a year and a halfand then the sisters spent six weeks in Borst, a remotemountain village in southern Austria. One canvas paintedthere, Peasant Women of Borst, was purchased by thesubscription of seventeen prominent Cincinnati women forthe new Cincinnati Art Museum which they had beeninstrumental in establishing. It was hung there in a carvedoak frame donated by Benn Pitman.

The sisters returned to Paris for the winter,but in July 1892 they were off again to work in Holland forthree months. In the fishing village of Volendam, a favoriteof many artists, they shared a cottage with Laura andHenriette Wachman, expatriate friends from Cincinnati.Elizabeth and Henriette, the painters, had a platform con-structed outside their studio window so that they couldwork even in cold, windy weather. Elizabeth worked soprodigiously that she finished four large paintings as well assome twenty-two smaller ones during that happy summer.

In a 1915 letter Anna Schmidtwrote: "I was with Elizabethwhen she painted that girl onthe Etaples Dunes—it was socold and windy the model usedto weep...the picturepossesses in a striking degree

that stormy atmosphere of theFrench coast on windy falldays..." Fisher Girl of Picardywas given to the SmithsonianInstitution's fine-arts collectionby Elizabeth Pilling, sister ofAnna Schmidt.

Intrigued by the Bigoudinepeople and their colorful cos-tumes Nourse returned toPenmarc'h for three consecu-tive years to paint. Rentrant deeglise, Penmarc'h was painted

during her first year atPenmarc'h.

Spring 1983 Elizabeth Nourse

In April 1893 the Nourses returned to Cin-cinnati because Adelaide was ill with consumption. Duringthe summer the artist traveled to Chicago for the ColumbianExposition where her three paintings shown in the Palace ofFine Arts received a medal. Two of her paintings were alsoon loan in the Cincinnati Room of the Woman's Buildingat the Fair.

Adelaide died on September 12, 1893. Thisleft Elizabeth and Louise as the only surviving members oftheir immediate family. It was a tragic loss for the artist who

had always felt a special closeness to her twin and from thattime on she apparently decided to make Paris her home. Sheand Louise always retained their American citizenship andmaintained a deep interest in their Cincinnati relatives andfriends, but Paris provided an art community second tonone and the Nourses found that they could live with greaterfreedom there as single women and also maintain a higherstandard of living. By selling her paintings to Americans,Nourse benefited from the exchange rate of five francs to thedollar, and the sisters reported in 1900 that they could livesimply on $ 1,000 a year and, if they had any more, they

considered themselves rich.Returning to Paris in 18 94, the Nourses found

a studio at 80 rue d'Assas in the Latin Quarter where theywere to live for the rest of their lives. It afforded a splendidview of the Luxembourg Gardens, and over the years theywere able to sublet it frequently to help fianance their workingtrips in search of fresh subject matter for Elizabeth in theFrench countryside. Brittany became one of their favoritepainting locales, particularly the remote village of Penmarc'hwhere they boarded in a local convent, at a cost of $1.00 aday each, and made many friends among the villagers.

Peasant Women of Borst whichseventeen Cincinnati womenhad purchased for the CincinnatiArt Museum hung in the Cin-cinnati Room of the ColumbianExposition in Chicago.

She received a medal for threeof her paintings shown inthe Palace of Fine Arts atthe Columbian Exposition inChicago.

Queen City Heritage

Louise Nourse wrote that theprice for Dans I'eglise aVolendam was $700 althoughshe had sold it once for $ 1,000,the buyer decided it was toolarge and exchanged it for two

small pictures priced at$500 each.

Although there is no recordthat Nourse ever consultedFrank Duveneck, renown Cin-cinnati artist and teacher, herpainting Old Man and Childindicated she experimented

with the bravura brushwork ofhis early canvases.

The Cincinnati Public Schoolsown her Interieur breton,Plougastel which exhibited atthe New Salon in 1908.

Spring 1983

ft

„ • - ' ^ . • • • • •

r »^r\ t

Inscribed "Em Pit," this drawingof Emerson Pitman, Nourse'snephew, was given to her niecein 1929. Both drawings arepart of the Nourse Collectiondonated to the HistoricalSociety by Melrose Pitman.

Nourse made this drawing ofher twin sister when the twowere fourteen and gave it toAdelaide's daughter, MelrosePitman, many years later.

14

In 1897 the Nourses spent three months inTunis visiting the Wachman sisters who were living there.The artist's palette had been brightening for some years, butthe influence of tropical sunshine caused her to use morevivid colors than she had in the past. Her dramatic portrait,Head of an Algerian, illustrated this new interest in rich color.

The Nourses and the Wachmans had anotherpair of Cincinnati friends who also became expatriates, Helenand Mary Rawson, with whom they visited over the years.In 1901 the Nourses spent some time at the Rawsons'villa in Menton where Elizabeth sketched their niece, MarthaRawson at Menton, against the background of the Rivieracoast. It illustrated the bold drawing technique that wonher election to the New Salon board as societaire. Pastelwas her favorite medium for portraiture and, through theyears, she executed many commissions for Parisian friendsand for Americans visiting Paris.

For the Salon Nourse continued to paintstraightforward portraits of ordinary peasants, such asNormandy Peasant Woman and Child in which she showedthe child gazing directly at the viewer while the mother

Queen City Heritage

averts her head. As she frequently did, here she emphasizedthe contrast between the mother's weathered hands and thechild's tender skin. Anna Schmidt reported that severaldealers objected to her ugly peasants and asked her to paintsomething pretty that would sell. Nourse refused to com-promise her belief, however, that there was beauty in thecommonplace and said that she could not paint what didnot appeal to her.

Through the years Nourse was preoccupiedwith illustrating light in both her watercolor and oil paintings.She could capture the fugitive light of sky and water swiftlyin watercolor. In her oils, she experimented with light ofevery day and season of the year with artificial light, lamplightand firelight. A Salon painting, Les violets clos, featuring bothinterior and exterior light, became the most important workof her career when it was purchased in 191 o by the Frenchministry of Fine Arts for the state's permanent collection inthe Luxembourg Museum. This official recognition of herwork caused her to be acclaimed by at least forty critics at theSalon and occasioned much publicity in English and Ameri-can newspapers as well.

Buoyed by this success, Nourse painted Lareverie for the next Salon, an even bolder experiment withsunshine flooding a dim interior in which a woman's figure,composed of vivid shades of blue, green, and violet, is almostdissolved by the light as in an Impressionist painting. Thiswork was left in her estate and her executor, Walter S.Schmidt, donated it and thirty-one other Nourse paintingsto the College-Conservatory of Music (now a part of the

Her dramatic portrait, Head ofan Algerian, illustrated her newinterest in rich color.

Nourse painted straightforwardportraits of ordinary peasantsin which she emphasized thecontrast between the mother'sweathered hands and the child'stender skin as in NormandyPeasant Woman and Child

now owned by the CincinnatiArt Museum.

University of Cincinnati) where he served as chairman of theboard of trustees.

Nourse was at the peak of her career in theseyears just prior to World War I. She worked prodigiously totake advantage of all the requests to exhibit her paintings. InJuly 1914, however, the Germans invaded Belgium and thewar marked the end of the art world as Nourse knew it. TheSalon lost its importance as dealers in London, Paris andNew York attracted the public by showing a rapid successionof modern styles.

Most of the American expatriates in Paris wenthome, but the Nourses felt an obligation to their adoptedcountry, and they remained and worked tirelessly for the

refugees who flooded into Paris. Elizabeth solicited donationsfrom many American and Canadian friends. Anna Schmidtwas particularly active in raising funds for her in Cincinnati,Boston, and Gloucester. Nourse was especially concernedwith aiding artists whose lives were now disrupted by thewar, and in 1919 the board of the New Salon presented herwith a silver plaque in recognition of this work.

In March 1920 Elizabeth underwent surgeryfor breast cancer and was unable to paint at her easel forsome time. She exhibited three works in the Salon of 1921that had been painted some years previously, and by 1924she ceased to exhibit at all. She was sixty-five years old andher professional career had spanned forty-four years.

— .• ! 9 ° J t h e N o u r s e s spent time In the early twentieth centu77

at the Rawsons' villa in Menton Nourse's work was reproducedand while there Elizabeth ~- •= •- -•-*sketched Martha Rawson atMenton.

- — - . . ww w » T V I ix vvao i ^LJI UUUUc

on French picture postcards.

16 Queen City Heritage

>;•-,..

DISCE-QUASI-SEMPER-VICTURUS--VIVE- QUASI- CRAS-MOR1TVRVS

NOTRE DAME, INDIANA, MA

TO A MELTING SNOWFLAKE.

CUNSHINE, thHas lured youA guileless thinWllr ill ha

.g that lricy brea

But languish ere the day.Albeit happily,After your bit of play.

MISS ELIZABETH NOURSE,LAETARE MEDALIST.

W *if PON Miss Elizabeth Nourse, foremostI I of the women artists of America,V J the University of Notre Dame this

year confers the highest honor withmits power, an honor symbolical of the pre-eminence of a lay Catholic of America, theLaetare Medal. Not only on account of herachievement in her profession but by reasonof her untiring and effective efforts to betterand beautify the lives of others is Miss Noursemost worthy to be added to the august groupof Laetare Medalists.

Miss Nourse, a descendent of the RebeccaNourse family of Salem, Massachusetts, was

In 1921 Nourse received one last public honorthat must have been gratifying for her. The University ofNotre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, awarded her the LaetareMedal, given annually to a Catholic layperson for distin-guished service to humanity. The Paris edition of the NewYork Herald described the ceremony, presided over by thePapal Nuncio in Paris, and called Nourse "the dean of Amer-ican woman painters in France and one of the most eminentcontemporary artists of her sex." The Chicago Tribune simplyreferred to her as "the first woman painter of America."Elizabeth was probably not completely happy with suchtributes since she once told her friend, Anna Schmidt, thatshe wanted to be judged as an artist, not as a woman. She hadbecome accustomed, however, to hearing her work praisedfor showing "the strength of a man."

In retirement the Nourses enjoyed visits frommany of their Cincinnati relatives and friends. In 1926 Louisewrote that so many Cincinnatians visited their studio that"Little by little we see the whole town." When Louise died in1927 at the age of eighty-four, Elizabeth immediately becameill and was hospitalized. She lingered on for a year and a half,but after the loss of her sister, she lost all interest in the worldaround her. She died on October 8, 1938, and was buriedbeside Louise in the parish cemetery in St. Leger, a villageforty-five miles southwest of Paris which had been theirfavorite country retreat. She left the bulk of her estate to herfour nieces and all of her remaining art work to her executor,Walter S. Schmidt, a Cincinnati realtor who had managedher affairs after his father's death in 1911.

Born with great natural ability, ElizabethNourse received excellent training at the School of Design,but more than this was needed for her to achieve internationalprominence at a time when few women artists were takenseriously. She brought to her work a spiritual dimension thatenabled her to express deep personal convictions aboutbeauty and about the importance of the daily life and workof ordinary women, whom she portrayed with sympathyand respect. She was a Victorian lady with all the virtues weassociate with them—she was religious, devoted to her fam-ily, patriotic, and hard working. Yet, she was also independent,courageous, and determined to make a successful career in afield where many men failed to earn a living. Her life atteststo the fact that her dedication was an inspiration to thenumerous women who supported her, publicized her, andadmired and purchased her art.

1 Unless otherwise noted, all information on Nourse is taken from Mary

Alice H e e k i n Burke , Elizabeth Nourse, 1 859-1 9 3 8 : A Salon Career

(Washington, D.C., 1983).

An enlarged version of the exhibition opened for a seven-week showing

on May 13, 1983, at the Cincinnati Art Musuem.

William H. Truettner, Introduction to Elizabeth Nourse, 1859-1938, A

Salon Career pp . 12-13.

Kenneth R. Trapp, "Toward a Correct Taste: Women and the Rise of

the Design Reform Movement in Cincinnati 1947-1880;" Celebrate

Cincinnati Art, (Cincinnati, 1982), p. 51.

Anita Ellis, "Cincinnati Art Furniture," Antiques, April 1982, p. 931.

In 1921 the University of Notre

Dame in South Bend, Indiana

awarded Nourse the Laetare

Medal, given annually to a

Catholic layperson for distin-

guished service to humanity.