do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

-

Upload

hamletquiron -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 1/12

Comparing sense of coherence, depressive symptoms and anxiety,and their relationships with health in a population-based study*

Hanna Konttinen a,*, Ari Haukkala a, Antti Uutela b

a Department of Social Psychology, University of Helsinki, Unioninkatu 37, P.O. Box 54, 00014 Helsinki, Finland b National Public Health Institute, Finland

Available online 11 March 2008

Abstract

The strong negative correlations observed between the sense of coherence (SOC) scale and measures of depression and anxiety

raise the question of whether the SOC scale inversely measures the other constructs. The main aim of the present study was to

examine the discriminant validity of the three measures by comparing their associations with health indicators and behaviours.

The participants were 25 to 74-year-old Finnish men (n¼ 2351) and women (n¼ 2291) from the National Cardiovascular Risk

Factor Survey conducted in 1997. The SOC scale had high inverse correlations with both depression ( r ¼À0.62 among both

men and women) and anxiety measures (r ¼À0.57 among the men and r ¼À0.54 among the women). Although confirmatory

factor analyses suggested that it was possible to differentiate between SOC, cognitive depressive symptoms and anxiety, the

estimated correlations were even higher than those mentioned above. Education was related only to SOC, but the associations

of SOC, cognitive depressive symptoms and anxiety with self-reported and clinically measured health indicators (body mass index,

blood pressure, cholesterol) and health behaviours were almost identical. The variation in the lowest SOC tertile was more stronglyassociated with health variables than in the highest tertile. To conclude, the size of the overlap between the SOC and depression

scales was the same as between depression and anxiety measures. This indicates that future studies should examine the discriminant

validity of different psychosocial scales more closely, and should compare them in health research in order to bring parallel

concepts into the same scientific discussion.

Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Finland; Sense of coherence; Depression; Anxiety; Health; Psychological measurement; Discriminant validity; Mental health

Introduction

Personality and emotional factors have long been

suggested to have an influence on physical health.

Research efforts have been directed to the negative

emotions (e.g., hostility, depression, anxiety) hypothe-

sized to affect disease onset and development (Suls &Bunde, 2005), as well as, positive psychosocial vari-

ables (e.g., optimism, social support, sense of coher-

ence) that are assumed to maintain and enhance

health. The tendency among researchers has been to

evaluate the independent effects of different psychoso-

cial factors on physical health, while ignoring possible

overlap among variables (Kaplan, 1995). Sense of

coherence (SOC) attracted a lot of attention after the

development of a quantitative scale to measure it.

* Support to conduct this research was provided by the Signe and

Ane Gyllenberg Foundation.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ358 919124878.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (H. Konttinen),

[email protected] (A. Haukkala), [email protected]

(A. Uutela).

0277-9536/$ - see front matter Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.053

Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e2412www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 2/12

Nevertheless, researchers such as Geyer (1997) have

criticized the ambiguity of the scale and its lack of dis-

criminant validity in relation to the measures of depres-

sion and anxiety.

The sense of coherence construct

Antonovsky (1979, 1987, 1993) proposed a saluto-

genic orientation focusing on factors that protected

individuals’ health. He defined the central concept,

SOC, as an orientation towards life that characterises

the extent to which an individual appraises internal

and external environments as (1) comprehensible, (2)

manageable and (3) meaningful. Antonovsky (1987)

developed these three interrelated dimensions and the

SOC questionnaire on the basis of interviews with

persons who had experienced severe trauma. He

maintained that SOC has much in common with thepsychological constructs of hardiness (Kobasa, 1982),

locus of control (Rotter, 1966) and self-efficacy

(Bandura, 1977).

The SOC scale exists in two forms: the original

29-item questionnaire and the shortened version

including 13 items from the full form. Antonovsky

(1987, p. 87, 1993) designed each item to represent

one of the three dimensions, but he emphasized that

the scale measured the SOC construct unidimension-

ally. The structure of the SOC measure has since

been investigated using both exploratory and confirma-tory factor analysis, but with inconsistent results. Some

studies employing exploratory factor analyses have

supported the one-factor structure proposed by

Antonovsky (e.g., Frenz, Carey, & Jorgensen, 1993),

but other results have also been obtained (e.g., Sandell,

Blomberg, & Lazar, 1998). Furthermore, a confirma-

tory factor analysis study on the 13-item SOC

questionnaire conducted among Finnish working-aged

people found support for the three-factor model (Feldt

et al., 2006). Klepp, Mastekaasa, Sorensen, Sandanger,

and Kleiner (2007), on the other hand, preferred the

one-factor solution for a brief nine-item SOC scale

because the factors in the two- and three-factor models

were very strongly correlated, and the factor scores had

similar correlations with measures of psychological

well-being, depression and anxiety.

The SOC theory hypothesizes that an individual

with a strong SOC maintains and enhances health

through effective and flexible coping with stressors,

such as by adopting health-enhancing and avoiding

unhealthy behaviours (Antonovsky, 1987). An individ-

ual with a strong SOC is also more likely to perceive

internal and social environments as non-stressful.

SOC reduces the health-damaging effects of stress by

lowering the probability of adverse physiological

reactions and negative emotions associated with stress

perceptions. Antonovsky (1987) emphasized that the

consequences of stressors may be negative, neutral or

positive, depending on their nature and the adequacy

of coping. It is also possible that persistent or serious

health problems may influence the development of

SOC.

Numerous cross-sectional studies have found SOC

to be positively associated with physical and psycho-

logical health (Flannery & Flannery, 1990; Larsson

& Kallenberg, 1996; Lundberg, 1997; Pallant & Lae,

2002; Suominen, Blomberg, Helenius, & Koskenvuo,

1999), and health behaviours (e.g., alcohol problems

and physical activity) (Kuuppelomaki & Utriainen,

2003; Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom, & Polen, 1992).

There have been a few longitudinal studies investigat-ing whether SOC predicts health outcomes (e.g., all-

cause mortality and subjective state of health). Most

of these have supported its predictability (Suominen,

Helenius, Blomberg, Uutela, & Koskenvuo, 2001;

Surtees, Wainwright, Luben, Khaw, & Day, 2003),

but inconsistent results have also been reported.

Kivimaki, Feldt, Vahtera, and Nurmi (2000) found in

their study of municipal employees that SOC predicted

sickness absence only among the women. Other

research among people with chronic illness reported

reciprocal causation between SOC and domains of health (Veenstra, Moum, & Roysamb, 2005). Overall,

the SOC relationship with psychological well-being

seems to be stronger and more direct than that with

physical health (Eriksson & Lindstrom, 2006).

Depressive symptoms and anxiety

The conceptual and empirical relationship between

depression and anxiety has been studied extensively,

and the evidence suggests that it is difficult to differen-

tiate these two constructs empirically. The emotion of

fear has a central role in anxiety, which involves

feelings of worry, apprehension and dread (Watson &

Kendall, 1989). The essential characteristic of depres-

sion is sadness, with associated feelings of sorrow,

hopelessness and gloom. Self-reported depression and

anxiety have been highly correlated (typically between

0.45 and 0.75) in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric

samples (Clark & Watson, 1991). Considerable co-

morbidity has also been observed (Mineka, Watson,

& Clark, 1998).

The strong relationship between depression and

anxiety may reflect problems with existing scales

2402 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 3/12

and constructs. There is an overlap in many of the

symptoms that define both syndromes, and many

self-report scales also contain items that actually

measure the other construct (Gotlib & Cane,

1989). Thus, Clark and Watson (1991) proposed a tri-

partite model of depression and anxiety: general

distress or negative affect is common to both, while

manifestations of low positive affect are specific to

depression, and symptoms of somatic arousal signify

anxiety.

The two best-known theories of depression are

perhaps Beck’s (1967, 1987) cognitive theory and

Abramson, Metalsky, and Alloy’s (1989) hopelessness

theory. They both posit that cognitive vulnerability and

negative life stress together precipitate depression.

According to Beck (1987), dysfunctional attitudes

involving feelings of loss, inadequacy, failure and

worthlessness constitute cognitive vulnerability todepression, whereas in the view of Abramson et al.

(1989), cognitive depression diathesis encompasses

the general tendency to attribute negative events to sta-

ble and global causes, to infer negative consequences,

and/or to infer negative characteristics about the self.

In addition, Beck (1987) postulates that all depressed

people show a cognitive triad: automatic thoughts

reflecting negative views of the self, the world and

the future. It is suggested that the degree of this

negative thinking is directly related to the severity of

other depressive symptoms.The SOC construct could be integrated as a protec-

tive/risk factor into vulnerability-stress models of

depression. Individuals with a strong SOC should be

better able to maintain their emotional well-being in

stressful situations, whereas those with a weak SOC

share some of the cognitive vulnerability factors men-

tioned in Abramson et al.’s (1989) and Beck’s (1967)

theories. All this raises a question concerning vulnera-

bility and protective factors in general: do they form

different dimensions or are they merely opposite ends

of a continuum? Antonovsky (1987) considered risk

and protective factors qualitatively different. The

SOC construct also shares similarities with cognitive

and emotional features of depression, which raises

the question of whether a weak SOC represents depres-

sion. Overall, SOC describes individuals’ cognitive

and emotional functioning on a more general level

than theories of depression. In addition, the SOC

theory is more oriented towards societal determinants

(e.g., education) of health than depression theories.

There is evidence that people in higher socio-economic

positions have a stronger SOC (Lundberg & Nystrom

Peck, 1994).

The relationship of SOC with depressive

symptoms and anxiety

High negative associations have been consistently

observed between the SOC scale and measures of

depressive symptoms and anxiety. In studies published

between 1992 and 2003, the correlation coefficients

between the scale and different measures of anxiety

and depression varied from À0.29 to À0.82 and

from À0.34 to À0.90, respectively (Eriksson & Lind-

strom, 2005). Gruszczynska (2006) calculated the

mean weighted SOC correlations on the basis of 17

studies: À0.70 for anxiety and À0.65 for depression.

The size of these correlations raises doubts about the

construct validity of the SOC questionnaire. Thus, it

has been proposed that rather than being a measure

of resilience, the scale measures inversely negative

affectivity/neuroticism (Frenz et al., 1993; Strumpfer,Gouws, & Viviers, 1998; Watson & Clark, 1984).

There are a few studies that have investigated the

relationships between SOC, anxiety, and depression.

When confirmatory factor analysis was used, the 29-

item SOC scale loaded on the same latent variable as

the measures of trait anxiety, neuroticism, optimism,

depression and self-efficacy (Gruszczynska, 2006),

and also on both the health-proneness and negative-

affect factors (Kravetz, Drory, & Florian, 1993). Feldt,

Metsapelto, Kinnunen, and Pulkkinen (2007) found

that a high SOC (measured on the 13-item question-naire) was strongly associated (r ¼À0.86) with

reversed neuroticism in their confirmatory model.

Korotkov (1993) concluded from his four-week

prospective study that the 13-item SOC instrument

lacked face, construct and predictive validity, and

that most of the items measured emotionality (neurot-

icism) rather than SOC. Meanwhile, Breslin, Hepburn,

Ibrahim, and Cole (2006) recently analysed the longi-

tudinal relationship between psychological stress and

the 13-item SOC scale, and found that the stable

components of distress and SOC were strongly inter-

correlated (r ¼ 0.86). On the other hand, Strumpfer

et al. (1998) conceptualised the low end of negative af-

fectivity as emotional stability, and interpreted the

strong negative associations between both versions of

the SOC instrument and the negative-affectivity scales

as supporting the validity of the instrument. However,

the SOC measures were more strongly associated

with negative than with positive emotionality.

In sum, the few previous studies focusing on the

relationship between the SOC scale and measures of

negative emotions have yielded inconclusive results.

SOC, depressive symptoms and anxiety have all been

2403 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 4/12

related to various health indicators and behaviours, but

to our knowledge their associations with health-related

variables have not been compared in any previous

study. The purpose of the present study therefore was

to investigate the discriminant validity of the SOC,

depression and anxiety scales in a population-based

sample. In more specific terms: (1) first, we examined

the strength of the correlations between the measures

of SOC, depressive symptoms and anxiety, and con-

firmed these with a confirmatory model that takes mea-

surement error into account. (2) Our main aim was to

assess the discriminant validity between SOC, depres-

sion and anxiety scales by comparing their associations

with subjective and objective (body mass index, blood

pressure, total cholesterol) health indicators, health

behaviours and sociodemographic factors. If the SOC

scale and the measures of depressive symptoms and

anxiety are distinct measures, they should also bedifferentially related to other variables. (3) Finally,

we wished to find out whether variation in the SOC

was more strongly related to health variables at the

high or low end of the distribution. The questionnaire

produces variation among individuals with a weak

and a strong SOC. Most depression inventories, on

the other hand, do not account for variation among

the non-depressed as they assess only the intensity of

depressive symptoms. Antonovsky specifically hypoth-

esized that a strong SOC, and not just the absence of

weak SOC, protected health. If variation at the highend were associated with health measures, then this

would give the SOC scale an advantage over depres-

sion measures.

Methods

Participants

The participants comprised a random sub-sample of

the national cardiovascular risk factor survey (FIN-

RISK) conducted in Finland in 1997 (Vartiainen

et al., 2000). FINRISK 97 covered a random sample

of 11,500 people aged 25e74 drawn from the Finnish

population registers in five areas, (1) North Karelia

Province, (2) Kuopio Province, (3) South-Western

Finland, (4) the cities of Helsinki and Vantaa in the

capital area, and (5) the northern province of Oulu.

The sample was stratified according to gender,

10-year age groups, and area. In the age bracket

25e64 years there were 250 men and 250 women in

each 10-year age group in each region. In addition,

the sample included 500 men and 250 women aged

65e

74 from North Karelia Province and from the

Helsinki metropolitan area, respectively. Two-thirds

of these participants were randomly assigned to the

present study of psychosocial factors (n¼ 7103).

The participants received by mail a self-adminis-

tered health questionnaire including questions on soci-

odemographic factors (gender, education and income),

health behaviours (smoking and alcohol consumption),

and health (self-rated health, visits to a physician,

somatic and psychological symptoms). They were

asked to fill in the questionnaire at home, and to return

it to the health centre when they came for a medical

examination in which their weight, height and blood

pressure were measured, and blood samples were

taken. A self-administered psychosocial questionnaire

was then given to a sub-sample of these participants,

to be answered afterwards at home. This comprised

a 13-item SOC questionnaire followed by a 21-item

depression inventory and a six-item anxiety inventory.All three scales were separated by a number of other

items. Only the respondents who participated in all

three phases were included in the present study. The

final response rate was 67% (men, n¼ 2351; women,

n¼ 2291).

Measures

Sense of coherence (SOC)

We used a Finnish-language version of Antonov-

sky’s (1987) 13-item orientation to life questionnaireconsisting of four meaningfulness, five comprehensi-

bility, and four manageability items to measure SOC

(for the items and their order in the questionnaire,

see Fig. 1). The respondents were asked to indicate

the number that expressed their feeling best on

a seven-point scale with two anchoring phrases (e.g.,

1¼ very often, 7¼ very seldom or never). As recom-

mended initially by Antonovsky (1993) and recently

by Feldt et al. (2006), one total SOC score was calcu-

lated from the ratings of the 13 questions. The SOC

scores varied from 16 to 91, the higher scores reflecting

stronger SOC. The scale was internally consistent on

the basis of the Cronbach’s alpha criterion (0.86).

Confirmatory factor analysis (with maximum likeli-

hood estimation) was used to compare the applicability

of a one-factor and a correlated three-factor model of

the SOC items to the present data. An adequate fit

was obtained for both models after four error-term

covariances in the one-factor and one error-term

covariance in the three-factor solution were released:

c2 (61)¼ 838.20, p< 0.001; comparison fit index

(CFI)¼ 0.95; root mean square error of approximation

(RMSEA)¼ 0.06 (CI 90%: 0.05e

0.06); Akaike’s

2404 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 5/12

information criterion (AIC)¼ 898.20 for the one-factor

model, and c2 (61)¼ 1006.32, p< 0.001; CFI¼ 0.94;

RMSEA¼ 0.06 (CI 90%: 0.06e0.06); AIC¼ 1066.32

for the three-factor model. The factors were highly

correlated in the three-factor solution (r coÂma¼ 0.94;

r maÂme¼ 0.86; r coÂme¼ 0.76). The three-factor model

could be considered slightly better than the one-factor

model in which we had to release several error-term

covariances based on the largest modification indexes.

However, we decided to use the one-factor solution in

the later confirmatory model because the correlations

between the factors were so high (see also Klepp

et al., 2007).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured on the Finnish

version of the Beck depression inventory (BDI) (Beck,

Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961; Raitasalo,

1977). The BDI is a self-administered 21-item ques-

tionnaire covering the intensity of depressive symp-

toms. Each item includes four or five self-evaluative

statements, which carry a numerical value from 1 to

3 reflecting the intensity of the symptom. The respon-

dents were asked to choose for each item one statement

or more that best described their current situation. If

they had selected more than one option, which was

rare, the one indicating the highest level of depression

Depression

Pessimism

Punish-

ment

Self hate

Self-

accusations

Self-punitive

wishes

Crying

Irritability

Unsatis-

faction

Guilty

Indeci-

siveness

Mood

Failure

Social

withdrawal

.73

.64

.59

.61

.66

.51

.63

.55

.52

.49

.26

.50

.59

.35

.41

.40

.37

.43

.26

.54

.30

.28

.24

.07

.25

.34

Sense of

coherence

2 CO

6 CO

7 ME

8 CO

9 CO

10 MA

11 CO

4 ME

5 MA

13 MA

1 ME

3 MA

12 ME

.21

.15

.18

.29

.28

.36

.27

.53

.47

.14

.46

.51

Anxiety

Worried CalmContent Relaxed Upset Tense

.30

.46

.39

.42

.54

.52

.60

.52

.73

.69

.55

.37

.68

.71

.37

.20

.49

-.75

.76-.65

.60 .75 .76 .55 .71 .80

.36 .56 .58 .31 .51 .64

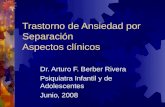

Fig. 1. The first-order correlated three-factor model of the SOC (sense of coherence) scale, BDI-13 (Beck depression inventory without the eight

somatic symptoms) and STAI (state anxiety inventory) with standardized parameter estimates (note: ME¼meaningfulness item;

CO¼ comprehensibility item; MA¼manageability item). The SOC items: 1 (ME) Do you have the feeling that you don’t really care what

goes on around you?; 2 (CO) Has it happened in the past that you were surprised by the behaviour of people whom you thought you knew

well?; 3 (MA) Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you?; 4 (ME) Until now your life has had: no clear goals or

purpose at all e very clear goals and purpose; 5 (MA) Do you have the feeling that you’re being treated unfairly?; 6 (CO) Do you have the feeling

that you are in an unfamiliar situation and don’t know what to do?; 7 (ME) Doing the things you do every day is: a source of deep pleasure and

satisfactione a source of pain and boredom; 8 (CO) Do you have very mixed-up feelings and ideas?; 9 (CO) Does it happen that you have feelings

inside you would rather not feel?; 10 (MA) Many people e even those with a strong character e sometimes feel like sad sacks (losers) in certain

situations. How often have you felt this way in the past?; 11 (CO) When something happened, have you generally found that: you overestimated or

underestimated its importance e you saw things in the right proportion; 12 (ME) How often do you have the feeling that there’s little meaning in

the things you do in your daily life?; 13 (MA) How often do you have feelings that you’re not sure you can keep under control?

2405 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 6/12

was coded on the data. We derived the BDI score by

summing up the ratings given to each of the 21 items.

It varied from 0 to 61 and showed good internal

consistency (Cronbach’s alpha¼ 0.87).

BDI covers eight somatic symptoms (distortion of

body image, work inhibition, sleep disturbance,

fatigability, loss of appetite, weight loss, somatic pre-

occupation and loss of libido) and 13 psychological

symptoms. A measure of depressive symptoms includ-

ing only these 13 psychological symptoms (referred to

as BDI-13 or cognitive depressive symptoms) was also

included as somatic symptoms could also indicate age-

ing and physical health problems.

Anxiety

The six-item short form of the state scale of the

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

(Marteau & Bekker, 1992) was used to measure stateanxiety: this has been found comparable to the full

form. The participants were asked to rate the six items

(e.g., ‘‘I am tense’’) from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very

much) according to how they felt at that moment.

The ratings given to each item were summed so that

higher STAI scores reflected higher anxiety. The short

form of the STAI was internally consistent (Cronba-

ch’s a¼ 0.85) and its range was from 6 to 24 in

this sample.

Self-rated healthThe question, What is your opinion about your cur-

rent health condition (1¼ very bad; 5¼ very good)?

was used to assess self-rated health.

Visits to a physician

Visits to a physician were covered by the question,

How many times have you visited a doctor during the

past year (12 months)?

Somatic and psychological symptoms

The participants were asked to indicate (from

1¼ often to 3¼ never) how often they had somatic

or psychological symptoms in the previous 30 days.

Somatic symptoms included tachycardia, trembling of

the hands, an irregular heart rate, dizziness, headache,

and sweaty palms, while psychological symptoms in-

cluded feeling confused when having to do something

quickly, feeling tense and nervous, having frightening

thoughts, feeling exhausted and overstrained, having

nightmares, depressiveness, and sleeplessness. The

mean scores of the ratings of the seven psychological

and six somatic symptoms were calculated separately

(Cronbach’s a¼ 0.81 and 0.67, respectively). The

scores varied from 1 to 3, the higher ones indicating

more symptoms.

Smoking status

Participants who reported that they had been

smoking regularly (more than once a day) for at least

a year, and had been doing so during the preceding

month, were classified as current smokers, and were

compared to former and never smokers in the analyses.

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed by means of

a self-report questionnaire inquiring into the usual

quantity and frequency of consuming various bever-

ages (Poikolainen, Poldkletnova, & Alho, 2002). The

average weekly alcohol consumption (grams of pure

alcohol per week) was estimated based on this

information.

Body mass index (BMI)

Body mass index was calculated as weight in

kilograms (measured to the nearest 100 g in light

clothing) divided by the square of height in meters

(measured to the nearest 0.5 cm).

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured twice after 5 min of

rest in a sitting position and the average systolic value

was used in the analyses.

Cholesterol

An enzymatic method was used to analyse the

serum total cholesterol value from serum samples.

Education

Education was assessed on a continuous scale based

on the self-reported number of years of schooling.

Income

Income was measured in terms of the self-reported

household gross income during the previous 12 months,

the response alternatives ranging from (1) less than

40,000 to (9) more than 320,000 Finnish marks (the

Finnish currency is now the euro, one euro correspond-

ing to 5.95 Finnish marks).

Statistical methods

Pearson correlation coefficients were used in

assessing the associations between the SOC, depressive

symptoms, anxiety and sociodemographic variables

(years of education were age-adjusted), and the

2406 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 7/12

relationships between the SOC scale, BDI-13 and

STAI were further examined by means of confirmatory

factor analyses (with maximum likelihood estimation).

Correlations with health and health-behaviour indica-

tors were controlled for age. We used a method for

testing the significance of the difference between the

dependent correlation coefficients in order to deter-

mine whether the SOC scale correlated with the health

indicators and behaviours to a significantly different

degree than BDI, BDI-13 or STAI (Cohen & Cohen,

1983). Finally, we tested equality of the strength of

the correlations among the SOC and various health-

related variables between the lowest and the highest

SOC tertiles (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). All the analyses

except the factor analyses were conducted separately

for men and women because this study included

variables (depressive symptoms and health-related

measures) that normally feature gender differences.Cases with missing values were excluded. Amos 7

and SPSS 15.0 were used.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for SOC,

depressive symptoms, anxiety and sociodemographic

factors, and the Pearson correlations between these

variables separately for men and women. Correlation

coefficients of less than 0.10 were not considered note-

worthy, although they became statistically significantdue to the large sample size.

The mean age was 51.3 years (SD¼ 13.8) for the

2065 men and 47.1 years (SD¼ 12.7) for the 2002

women (Table 1). The SOC mean score was 65.6

(SD¼ 11.8) among men and 64.8 (SD¼ 11.8) among

women, and was significantly higher for men ( p¼

0.006, h2¼ 0.002). The males (8.0, SD¼ 7.3) had

a significantly lower BDI mean score than females

(8.7, SD¼ 7.5) ( p¼ 0.001, h2¼ 0.003). A similar

phenomenon was observed when the eight somatic

symptoms of the BDI were excluded. In contrast, the

male and female STAI mean scores did not differ

(for the males: 10.4, SD¼ 3.0; for the females: 10.4,

SD¼ 3.1).

As Table 1 shows, SOC, depressive symptoms and

anxiety were highly associated in both genders. The

correlation between SOC and BDI was r ¼À0.62 for

all of the participants, and corresponding results were

found for BDI and STAI (r ¼ 0.64 in males and r ¼

0.65 in females). The association between SOC and

STAI (r ¼À0.57 for men and r ¼À0.53 for women)

was significantly lower than that between SOC and

BDI in both genders ( p< 0.01). The exclusion of the

eight somatic symptoms from the BDI did not affect

these correlations.

Confirmatory analysis was also used to investigate

the relations between SOC, cognitive depressive

symptoms and anxiety. A model was specified in

which cognitive and affective BDI items loaded on

the depression factor, the SOC items on the SOC fac-

tor, and the STAI items on the anxiety factor. These

three latent variables were specified to correlate. This

model did not fit the data adequately based on the fit

indexes: c2 (461)¼ 6345.43, p< 0.001; SRMR¼

0.04; CFI¼ 0.88; RMSEA¼ 0.06 (CI 90%: 0.05e0.06);

AIC¼ 6479.43. After three error-term covariances

between the SOC items were released on the basis of

the largest modification indexes, the model provided

a satisfactory fit with the data: SRMR¼ 0.04;

CFI¼ 0.91; RMSEA¼ 0.05 (CI 90%: 0.05e0.05);

AIC¼ 4712.18. The chi-square value was still signifi-cant (c2 (458)¼ 4572.18, p< 0.001), but the above-

mentioned fit indexes suggested that this was due to

the large sample size. As Fig. 1 indicates, the depres-

sion factor correlated highly with both the SOC and

anxiety factors (r ¼À0.75 and 0.76, respectively),

but it is possible to separate these constructs. The in-

ter-correlation of the SOC and anxiety factors was

also strong (r ¼À0.65).

The associations of SOC, depressive symptoms

and anxiety with sociodemographic factors were

somewhat different (Table 1). Age was related todepressive symptoms: the older men and women

were more depressed. However, this association

disappeared when the eight somatic symptoms of

the BDI were excluded. The younger participants

showed more anxiety, but these correlations were

weak (r ¼À0.07 among males and r ¼À0.06 among

females). Years of education were age-adjusted

because of the rapid rise in the level of education

in recent decades (r educationÂage¼À0.45 for the men

and r educationÂage¼À0.50 for the women, respec-

tively). Education was related to SOC, but not to

BDI, BDI-13 or STAI, after controlling for age:

more educated men and women had higher SOC

scores (Table 1). In contrast, income was associated

with SOC and depressive symptoms: SOC increased

and depression decreased as the income level rose.

We further investigated the discriminant validity of

the SOC scale by comparing the associations of SOC,

depressive symptoms and anxiety with health indica-

tors and health behaviours. Higher SOC scores and

lower depression and anxiety scores were related to

better self-rated health, fewer visits to a doctor, and

less somatic and psychological symptoms in both

2407 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 8/12

genders (Table 2). There were some differences be-

tween the males and females: SOC, depressive symp-

toms and anxiety were all related to smoking and

alcohol consumption among the men, but no such asso-

ciations emerged among the women. However, SOC,

BDI, BDI-13 and STAI showed no associations with

BMI, systolic blood pressure or total cholesterol levels

in either gender. These results suggest that SOC, de-

pressive symptoms and anxiety have inverse but other-

wise comparable relations with health indicators and

behaviours.

A comparison of the magnitude of the correlations

listed in Table 2 showed that BDI had significantly

higher correlations with self-rated health, psychologi-

cal and somatic symptoms, and visits to a physician

than the SOC scale ( p< 0.01). However, this differ-

ence remained significant only for psychological

symptoms among males when the eight somaticsymptoms were excluded. Comparisons between the

SOC scale and STAI indicated that these variables

were associated with all health indicators and health

behaviours to the same degree in both genders. Thus,

of the 54 comparisons of correlation coefficients, 45

indicated relationship equality.

The SOC score tertiles were then used to investigate

whether the variation in a low or high SOC was more

strongly associated with health and health-behaviour

variables. As Table 3 shows, SOC was related to self-

rated health and visits to a physician among the menand women whose SOC score fell into the lowest

SOC tertile, but there were no such relations in the high-

est tertile ( p< 0.05). SOC was associated with somatic

and psychological symptoms in both the lowest and

highest tertiles, but the correlations were stronger in

the lowest tertile among the men ( p¼ 0.035 for somatic

and p< 0.001 for psychological symptoms). The

strength of the associations among SOC and alcohol

consumption, smoking, BMI, blood pressure and cho-

lesterol were equal between the lowest and highest

tertiles, but all these correlations were low and most

of them were non-significant.

Discussion

We found strong relationships between the SOC

scale and measures of depressive symptoms and

anxiety in a representative population sample of 25

to 74-year-old Finnish people. These associations

became stronger when we applied structural equation

modelling, which takes measurement error into

account. The main aim of our study was to examine

the discriminant validity between the SOC, depression T a

b l e 1

T h e c o r r e l a t i o n c o e f fi c i e n t s b e t w e e n S O C , d

e p r e s s i v e s y m p t o m s , a n x i e t y a n d t h e s o c i o

d e m o g r a p h i c v a r i a b l e s

M e n ( n ¼

2 0 6 5 )

W o m e n ( n ¼

2 0 0 2 )

S O C

B D I

B D I - 1 3

S T A I

M e a n ( S D )

M i n e M a x

S O C

B D I

B D I - 1 3

S T A I

M e a n (

S D )

M i n e M a x

S O

C

1 . 0 0

6 5 . 6 ( 1 1 . 8 )

1 9 e 9 1

1 . 0 0

6 4 . 8 ( 1 1 . 8 )

1 6 e 9 1

B D I

À 0 . 6 2

1 . 0 0

8 . 0 ( 7 . 3 )

0 e 4 7

À 0 . 6 2

1 . 0 0

8 . 7 ( 7 . 5 )

0 e 4 6

B D I - 1 3

À 0 . 6 3

0 . 9 4

1 . 0 0

4 . 6 ( 5 . 1 )

0 e 3 4

À 0 . 6 2

0 . 9 5

1 . 0 0

5 . 2 ( 5 . 2 )

0 e 3 0

S T

A I

À 0 . 5 7

0 . 6 4

0 . 6 5

1 . 0 0

1 0 . 4 ( 3 . 0 )

6 e 2 4

À 0 . 5 3

0 . 6 5

0 . 6 3

1 . 0 0

1 0 . 4 ( 3 . 1 )

6 e 2 4

A g e ( y e a r s )

0 . 0 3 *

0 . 1 3

À 0 . 0 3 *

À 0 . 0 7

5 1 . 3 ( 1 3 . 8 )

2 5 e 7 4

À 0 . 0 0 *

0 . 1 4

0 . 0 3 *

À 0 . 0 6

4 7 . 1 ( 1 2 . 7 )

2 5 e 7 4

E d u c a t i o n ( y e a r s ) a

0 . 1 2

À 0 . 0 4

À 0 . 0 2 *

À 0 . 0 1 *

1 1 . 9 ( 4 . 1 )

1 e 5 4

0 . 1 1

À 0 . 0 6

À 0 . 0 4

0 . 0 3 *

1 1 . 9 ( 3 . 9 )

1 e 4 0

I n c o m e

0 . 2 0

À 0 . 1 6

À 0 . 1 3

À 0 . 0 9

0 . 1 7

À 0 . 1 6

À 0 . 1 3

À 0 . 0 6

* N

o t s i g n i fi c a n t ( a t t h e p <

0 . 0 5 l e v e l ) .

S O

C ¼

s e n s e o f c o h e r e n c e s c a l e ; B D I ¼

B e c

k d e p r e s s i o n i n v e n t o r y ; B D I - 1 3 ¼

B e c k d e p r e s s i o n i n v e n t o r y w i t h o u t t h e e i g h t s o m a t i c s y m p t o m s ; S T A I ¼

s t a t e a n x i e t y i n v e n t o r y .

a

A d j u s t e d f o r a g e .

2408 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 9/12

and anxiety scales by comparing their relations with

health-related and sociodemographic variables. Educa-

tion was related only to SOC, but the associations of

SOC, cognitive depressive symptoms and anxiety

with health indicators and health behaviours were

practically identical in both genders. Our eventual

aim was to find out whether variation at the high end

of the SOC distribution is related to health measures.

The inter-correlations among the SOC and health

variables were stronger among the respondents in the

lowest than among those in the highest SOC tertile.

The SOC scores had a high negative association with

both depression (r ¼À0.62 for the men and the women)

and anxiety (r ¼À0.57 for the men and À0.53 for the

women), which is consistent with previous findings

(Eriksson & Lindstrom, 2005). Although factor analy-

ses suggested that it was possible to differentiate

between the SOC, cognitive depressive symptoms andanxiety variables, the estimated correlations were

even higher than those mentioned above. The relation-

ship between SOC and depressive symptoms was as

strong as that between depressive symptoms and

anxiety. This was particularly interesting given

evidence from extensive studies on the close relation-

ship between depression and anxiety (Gotlib & Cane,

1989).

A comparison of the SOC and the BDI items

revealed some content overlap. Four meaningfulness

items and one manageability item (numbered 1, 4, 7,10 and 12, see Fig. 1) could be interpreted as reflecting

symptoms measured with the BDI (lack of satisfaction,

social withdrawal, sense of failure, guilty feeling and

self accusations), and two comprehensibility items

(numbered 8 and 9, see Fig. 1) seemed to assess

negative emotional experiences in general. In addition,

two manageability items and one comprehensibility

item (numbered 2, 3 and 5, see Fig. 1) were more likely

to measure interpersonal trust/mistrust than the man-

ageability or comprehensibility dimensions of SOC.

In previous factor-analytic studies, these items have

formed their own factor, which has been interpreted

as reflecting interpersonal trust or mistrust (e.g.,

Sandell et al., 1998). Factor analyses conducted on

the present data also indicated that the structure of

the SOC scale was rather ambiguous. This is no

wonder as half of the items could be interpreted as as-

sessing symptoms of depression or negative emotions.

The relationships of the SOC, depression and

anxiety scales with years of education revealed some

differences between these measures: educational level,

controlled for age, was associated only with SOC.

Household annual income, however, was associated T a

b l e 2

T h e a g e - a d j u s t e d c o r r e l a t i o n c o e f fi c i e n t s b e t w e e n S O C , d e p r e s s i v e s y m p t o m s , a n x i e t y

a n d h e a l t h - r e l a t e d v a r i a b l e s

M e n ( n ¼

1 9 5 4 )

W o m e n ( n ¼

1 9 4 3 )

S O

C

B D I

B D I - 1 3

S T A I

M e a n ( S D )

M i n e M a x

S O C

B D I

B D I - 1 3

S T A I

M e a n ( S D )

M i n e M a x

S e

l f - r a t e d h e a l t h

0 .

3 0

À 0 . 3 8

L 0 . 2

9

L 0 .

3 1

3 . 5 ( 0 . 8 )

1 e 5

0 .

2 6

À 0 . 3 4

L 0 .

2 7

L 0 .

2 8

3 . 7 ( 0 . 8 )

1 e 5

V i s i t s t o a p h y s i c i a n ( t i m e s / p a s t y e a r )

L 0 .

1 3

0 . 2 4

0 .

1 8

0 .

1 8

2 . 7 ( 4 . 2 )

0 e 9 9

L 0 .

1 4

0 . 2 1

0 .

1 6

0 .

1 7

3 . 5 ( 4 . 2 )

0 e 9 2

S o

m a t i c s y m p t o m s a

L 0 .

3 2

0 . 4 1

0 . 3

4

0 .

3 4

1 . 4 ( 0 . 3 )

1 . 0 e 2 . 8

L 0 .

3 2

0 . 4 1

0 .

3 7

0 .

3 3

1 . 5 ( 0 . 3 )

1 . 0 e 3 . 0

P s

y c h o l o g i c a l s y m p t o m s b

L 0 .

5 1

0 . 6 1

0 . 5 6

0 .

5 5

1 . 5 ( 0 . 4 )

1 . 0 e 3 . 0

L 0 .

5 3

0 . 6 0

0 .

5 7

0 .

5 4

1 . 6 ( 0 . 4 )

1 . 0 e 3 . 0

S m

o k i n g s t a t u s c

L 0 .

1 1

0 .

1 4

0 . 1

4

0 .

1 0

L 0 .

0 8

0 .

0 9

0 .

0 8

0 .

0 6

A l c o h o l c o n s u m p t i o n ( a b s . g / w e e k )

L 0 .

1 1

0 .

1 4

0 . 1

3

0 .

0 9

1 0 3 . 2 ( 1 4 9 . 3 )

0 . 0 e 1 5 1 . 5

L 0 .

0 2 *

0 .

0 1 *

0 .

0 3 *

0 .

0 4 *

4 2 . 6 ( 8 2 . 0 )

0 . 0 e 9 3 . 8

B M I ( k g / m

2 )

L 0 .

0 4 *

0 .

0 7

0 . 0

3 *

0 .

0 3 *

2 6 . 9 ( 3 . 8 )

1 4 . 7 e 4 7 . 9

L 0 .

0 6

0 .

0 7

0 .

0 4 *

0 .

0 1 *

2 6 . 1 ( 4 . 8 )

1 5 . 4 e 5 1 . 6

S y

s t o l i c b l o o d p r e s s u r e ( m m H g )

0 .

0 2 *

L 0 .

0 1 *

L 0 .

0 0 *

0 .

0 2 *

1 4 0 . 3 ( 1 9 . 6 )

7 8 . 0 e 2 1 9 . 0

0 .

0 4 *

L 0 .

0 4 *

L 0 .

0 4 *

L 0 .

0 5

1 3 1 . 5 ( 1 9 . 5 )

8 1 . 0 e 2 2 5 . 0

C h o l e s t e r o l ( m m o l / l )

L 0 .

0 2 *

0 .

0 2 *

0 .

0 4 *

0 .

0 2 *

5 . 6 ( 1 . 0 )

2 . 4 - 1 0 . 5

L 0 .

0 5

0 .

0 2 *

0 . 0

3 *

L 0 .

0 1 *

5 . 5 ( 1 . 1 )

2 . 7 e 1 0 . 3

* N

o t s i g n i fi c a n t ( a t t h e p <

0 . 0 5 l e v e l ) .

T h e s t r e n g t h o f t h e c o r r e l a t i o n c o e f fi c i e n t s m a r k e d i n b o l d i s s i m i l a r t o t h e c o e f fi c i e n t s b e

t w e e n S O C a n d d i f f e r e n t h e a l t h - r e l a t e d v a r i a b l e s . S O C ¼

s e n s e o f c o h e r e n c e s c a l e ; B D

I ¼

B e c k d e p r e s s i o n

i n v e n t o r y ; B D I - 1 3 ¼

B e c k d e p r e s s i o n i n v e n t o r y w i t h o u t t h e e i g h t s o m a t i c s y m p t o m s ; S T A I ¼

s t a t e a n x i e t y i n v e n t o r y ; B M I ¼ b o d y m a s s i n d e x .

a

A r a p i d h e a r t r a t e , s h a k i n g h a n d s , a n i r r e

g u l a r h e a r t r a t e , d i z z i n e s s , h e a d a c h e , a n d

s w e a t y h a n d s .

b

F e e l i n g c o n f u s e d w h e n h a v i n g t o d o s o m

e t h i n g q u i c k l y , f e e l i n g t e n s e a n d n e r v o u s , h a v i n g f r i g h t e n i n g t h o u g h t s , f e e l i n g e x h a u s t e d a n d o v e r s t r a i n e d , h a v i n g n i g h t m a r e s , d e p r e s s i v e n e s s , a n d

s l e e p l e s s n e s s .

c

N e v e r / f o r m e r s m o k e r s ¼

1 ; c u r r e n t s m o k

e r s ¼

2 .

2409 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 10/12

with both SOC and depression. In addition, the levels

of both SOC and depressive symptoms varied accord-

ing to gender: women had a significantly lower SOC

mean score and a higher BDI mean score than men.

Age was not related to SOC in these data, although

not all population studies have found SOC to be

independent of age (Larsson & Kallenberg, 1996).

Antonovsky (1987) developed SOC as an explana-tory concept related to health. Hence, the main interest

in this study was to compare the associations of SOC,

depressive symptoms and anxiety with health

indicators and behaviours. Consistent with the results

of previous studies (Eriksson & Lindstrom, 2006;

Friedman & Booth-Kewley, 1987), SOC was positively

and depressive symptoms and anxiety were negatively

associated with various health-related measures. The

full 21-item BDI includes eight somatic symptoms

that, in addition to depression, are directly related to

ageing and physical health (r ageÂBDI¼ 0.13 for the

men and 0.14 for the women). Thus, to avoid possible

bias, the 13-item BDI, which includes only cognitive

and affective symptoms (r ageÂBDI-13¼À0.03 for the

men and 0.03 for the women), is more appropriate in

terms of comparing the relationships of SOC and de-

pressive symptoms with health indicators. The SOC

scale, BDI-13 and STAI were associated to an equal

magnitude with all the subjective and objective health

indicators used in the present study. The only exception

was that BDI-13 had a significantly higher correlation

with psychological symptoms among the men than the

SOC measure. However, this difference was not

sizeable, becoming statistically significant due to the

large sample size (r SOCÂpsychological symptoms¼À0.51

and r BDI-13Âpsychological symptoms¼ 0.56). Furthermore,

the strength of the correlations of the SOC scale,

BDI, BDI-13 and STAI with health behaviours

(smoking and alcohol consumption) was consistent.

We also examined whether variation at the high end

of the SOC was related to health measures, as depres-sion inventories do not extend to the positive end. The

resulting analyses with the SOC tertiles indicated that

the variation at the low end was more strongly associ-

ated with health variables than the variation at the high

end. This is consistent with the findings reported by

Kivimaki et al. (2000): it was only a low and not

a high SOC that predicted health (sickness absence).

These results could be interpreted to imply that a strong

SOC is not necessary for good health, although it may

have a positive impact on other aspects of the quality

of life.

The present study included quite a wide range of

health-related measures: self-reported health indicators

and health behaviours, and clinically measured health

indicators (BMI, systolic blood pressure and total

cholesterol). SOC, depressive symptoms and anxiety

all had the strongest correlations with self-assessed

health variables. It is possible that self-reported health

indicators are confounded by psychological character-

istics and emotional states. For example, people with

depressive symptoms or anxiety may report more phys-

ical symptoms, and may visit a physician more often

because negative mood states result in negative biases

Table 3

The correlation coefficients between SOC and health-related variables by SOC tertiles

Men Women

Low SOCa

(n¼ 626)

Medium SOCb

(n¼ 717)

High SOCc

(n¼ 741)

Low SOCa

(n¼ 708)

Medium SOCb

(n¼ 682)

High SOCc

(n¼ 678)

Self-rated health 0.18*** 0.10** 0.06 0.20***À

0.01 0.00Visits to a physician (times/past year) À0.13** À0.01 À0.01 À0.17*** 0.05 À0.04

Somatic symptoms À0.25*** À0.06 À0.14*** L0.21*** À0.01 L0.13**

Psychological symptoms À0.39*** À0.10* À0.20*** L0.37*** À0.05 L0.31***

Alcohol consumption (abs. g/week) L0.10* À0.04 L0.03 L0.02 0.03 L0.05

Smoking statusdL0.06 À0.05 L0.02 L0.06 À0.05 L0.09*

BMI (kg/m2) L0.01 À0.03 0.01 L0.05 0.02 0.05

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 0.08* À0.00 0.04 L0.02 0.03 0.08*

Cholesterol (mmol/l) 0.04 0.02 L0.04 L0.03 À0.01 0.03

*** p< 0.001; ** p< 0.01; * p< 0.05.

The correlation coefficients marked in bold are equal in strength between the lowest and highest tertiles. SOC ¼ sense of coherence scale; BMI¼

body mass index.a Scores 16e60.b Scores 61e71.c Scores 72

e91.

d Never/former smokers¼ 1; current smokers¼ 2.

2410 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 11/12

in the evaluation and categorisation of stimuli (Cohen

& Rodriguez, 1995). In this study, SOC, depression

and anxiety were not related to clinically measured

health variables.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare

the relationships of SOC, depressive symptoms and

anxiety with health-related variables in a representative

population sample. A few earlier studies have compared

the associations of SOC and other personality traits with

health variables. The SOC scale has shown stronger cor-

relations with different health and well-being measures

than the self-efficacy, hardiness, locus of control, self-

esteem and optimism scales, for example (Pallant &

Lae, 2002; Smith & Meyers, 1997). Similar associations

found between the SOC, depression and anxiety

measures suggest that SOC has more in common with

them than other positive psychology concepts.

In the present study, we used the 13-item SOCquestionnaire, and it is possible that the heterogeneity

of the SOC construct would be better captured in the

full 29-item questionnaire. Furthermore, the depression

and anxiety inventories we used are not unproblematic

either: it is possible that one common factor, such as

negative emotionality, explains the strong and inverse

relationship of the SOC with depression and anxiety

(Frenz et al., 1993). Indeed, the SOC questionnaire

might measure negative emotionality, and according

to the tripartite model of depression and anxiety (Clark

& Watson, 1991), negative emotions common to bothdepression and anxiety are mainly responsible for the

strong association between the measures of these two

constructs.

In conclusion, our study provides additional

evidence of the overlap between the SOC scale and

measures of depression and anxiety. This is consistent

with the findings reported by Breslin et al. (2006),

Gruszczynska (2006) and Korotkov (1993). It seems

that current psychometric methods are able to separate

highly correlated measures, and these small differences

could have value in some research settings. However,

in view of our almost equal associations with health

indicators and behaviours, it would be useful to bring

these concepts into the same scientific discussion.

This kind of research could have a positive impact in

the application of these constructs to theory-based

health-improvement programmes.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopeless-

ness depression: a theory-based subtype of depression.

Psychological Review, 96 (2), 358e

372.

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How

people manage stress and stay well . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of

coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 36 (6), 725e733.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of

behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191e

215.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment . Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T. (1987). Cognitive models of depression. Journal of

Cognitive Psychotherapy, 1(1), 5e37.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J.

(1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of

General Psychiatry, 4, 561e571.

Breslin, F. C., Hepburn, C. G., Ibrahim, S., & Cole, D. (2006).

Understanding stability and change in psychological distress

and sense of coherence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,

36 (1), 1e21.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and

depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 316e336.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correla-

tion analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cohen, S., & Rodriguez, M. S. (1995). Pathways linking affective

disturbances and physical disorders. Health Psychology, 14(5),

374e380.

Eriksson, M., & Lindstrom, B. (2005). Validity of Antonovsky’s

sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. Journal of

Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(6), 460e466.

Eriksson, M., & Lindstrom, B. (2006). Antonovsky’s sense of

coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic

review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60,

376e381.

Feldt, T., Lintula, H., Suominen, S., Koskenvuo, M., Vahtera, J., &Kivimaki, M. (2006). Structural validity and temporal stability

of the 13-item sense of coherence scale: prospective evidence

from the population-based HeSSup study. Quality of Life

Research, 16 , 483e493.

Feldt, T., Metsapelto, R.-L., Kinnunen, U., & Pulkkinen, L. (2007).

Sense of coherence and five-factor approach to personality.

European Psychologist, 12(3), 165e172.

Flannery, R. B., & Flannery, G. J. (1990). Sense of coherence,

life stress, and psychological distress: a prospective

methodological inquiry. Journal of Clinical Psychology,

46 (4), 415e420.

Frenz, A. W., Carey, M. P., & Jorgensen, R. S. (1993). Psychometric

evaluation of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale. Psycholog-

ical Assessment, 5(2), 145e153.

Friedman, H. S., & Booth-Kewley, S. (1987). The ‘disease prone

personality’: a meta-analytic view of the construct. American

Psychologist, 42(6), 539e555.

Geyer, S. (1997). Some conceptual considerations on the sense of

coherence. Social Science & Medicine, 44(12), 1771e1779.

Gotlib, I. H., & Cane, D. B. (1989). Self-report assessment of

depression and anxiety. In: P. C. Kendall, & D. Watson (Eds.),

Anxiety and depression: Distinctive and overlapping features

(pp. 131e169). San Diego: Academic Press.

Gruszczynska, E. (2006). What is measured by the orientation to life

questionnaire? Construct validity of the instrument for the sense

of coherence measurement. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 37 (2),

74e

83.

2411 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412

8/8/2019 do Sense of Coherence Ansiedad y Sitnomas Depresivos

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/do-sense-of-coherence-ansiedad-y-sitnomas-depresivos 12/12

Kaplan, G. A. (1995). Where do shared pathways lead? Some

reflections on a research agenda. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57 ,

208e212.

Kivimaki, M., Feldt, T., Vahtera, J., & Nurmi, J. (2000). Sense of

coherence and health: evidence from two cross-lagged longitudi-

nal samples. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 583e597.

Klepp, O. M., Mastekaasa, A., Sorensen, T., Sandanger, I., &

Kleiner, R. (2007). International Journal of Methods in Psychiat-

ric Research, 16 (1), 11e22.

Kobasa, S. C. (1982). The hardy personality: toward a social psychol-

ogy of stress and health. In: J. Suls, & G. Sanders (Eds.), Social

psychology of health and illness (pp. 3e33). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Korotkov, D. (1993). An assessment of the (short-form) sense of

coherence personality measure: issues of validity and well-being.

Personality and Individual Differences, 14, 575e583.

Kravetz, S., Drory, Y., & Florian, V. (1993). Hardiness and sense of

coherence and their relation to negative affect. European Journal

of Personality, 7 (4), 233e244.

Kuuppelomaki, M., & Utriainen, P. (2003). A 3 year follow-up study

of health care students’ sense of coherence and related smoking,

drinking and physical exercise factors. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 40(4), 383e388.

Larsson, G., & Kallenberg, K. (1996). Sense of coherence, socioeco-

nomic conditions and health. European Journal of Public Health,

6 (3), 175e180.

Lundberg, O. (1997). Childhood conditions, sense of coherence,

social class and adult ill health: exploring their theoretical and

empirical relations. Social Science & Medicine, 44(6), 821e831.

Lundberg, O., & Nystrom Peck, M. (1994). Sense of coherence,

social structure and health. Evidence from a population survey

in Sweden. European Journal of Public Health, 4, 252e257.

Marteau, T. M., & Bekker, H. (1992). The development of a six-item

short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychol-

ogy, 31, 301e

306.Midanik, L. T., Soghikian, K., Ransom, L. J., & Polen, M. R. (1992).

Alcohol problems and sense of coherence among older adults.

Social Science & Medicine, 34, 43e48.

Mineka, S., Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1998). Comorbidity of

anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychol-

ogy, 49, 377e412.

Pallant, J. F., & Lae, L. (2002). Sense of coherence, well-being, cop-

ing and personality: further evaluation of the sense of coherence

scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(1), 39e48.

Poikolainen, K., Poldkletnova, I., & Alho, H. (2002). Accuracy of

quantity-frequency and graduated frequency questionnaires in

measuring alcohol intake: comparison with daily diary and

commonly used laboratory markers. Alcohol & Alcoholism,

37 (6), 573e576.

Raitasalo, R. (1977). Depression and its connections with need for

psychotherapy. Helsinki: Research Institute for Social Security.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus ex-

ternal control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1).

Sandell, R., Blomberg, J., & Lazar, A. (1998). The factor structure of

Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale in Swedish clinical and

nonclinical samples. Personality and Individual Differences,

24(5), 701e711.

Smith, T. L., & Meyers, L. S. (1997). The sense of coherence: its

relationship to personality, stress and health measures. Journal

of Social Behavior and Personality, 12(2), 513e526.

Strumpfer, D. J. W., Gouws, J. F., & Viviers, M. R. (1998). Antonov-

sky’s sense of coherence scale related to negative and positive

affectivity. European Journal of Personality, 12(6), 457e480.

Suls, J., & Bunde, J. (2005). Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk

factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications

of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychological Bulletin,

131(2), 260e300.

Suominen, S., Blomberg, H., Helenius, H., & Koskenvuo, M. (1999).Sense of coherence and health e does the association depend on

resistance resources? A study of 3115 adults in Finland. Psychol-

ogy & Health, 14(5), 937e948.

Suominen, S., Helenius, H., Blomberg, H., Uutela, A., &

Koskenvuo, M. (2001). Sense of coherence as a predictor of

subjective state of health: results of 4 years of follow-up of adults.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 50(2), 77e86.

Surtees, P., Wainwright, N., Luben, R., Khaw, K. T., & Day, N.

(2003). Sense of coherence and mortality in men and women in

the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom prospective cohort study.

American Journal of Epidemiology, 158(12), 1202e1209.

Vartiainen, E., Jousilahti, P., Alfthan, G., Sundvall, J., Pietinen, P., &

Puska, P. (2000). Cardiovascular risk factor changes Finland,

1972e

1997. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29, 49e

56.Veenstra, M., Moum, T., & Roysamb, E. (2005). Relationships

between health domains and sense of coherence: a two-year

cross-lagged study in patients with chronic illness. Quality of

Life Research, 14, 1455e1465.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: the disposi-

tion to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological

Bulletin, 96 (3), 465e490.

Watson, D., & Kendall, P. C. (1989). Understanding anxiety and

depression: their relation to negative and positive affective states.

In: P. C. Kendall, & D. Watson (Eds.), Anxiety and depression:

Distinctive and overlapping features (pp. 3e26). San Diego:

Academic Press.

2412 H. Konttinen et al. / Social Science & Medicine 66 (2008) 2401e 2412