Cynefin Place Programme Monitoring & Learning · Cynefin is a Welsh Government programme running...

Transcript of Cynefin Place Programme Monitoring & Learning · Cynefin is a Welsh Government programme running...

Cynefin Place Programme

Monitoring & Learning

Final research report for Welsh

Government

November 2015

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government Contents

November2015

Contents

Executive Summary i

1 Introduction 1

1.1 Background 1

1.2 Aims of the Cynefin change programme 1

1.3 Monitoring & Learning Methodology 3

2 Programme description 7

2.1 Structure of the programme 7

2.2 The Place Co-ordinators 9

3 Outcomes – headline findings 12

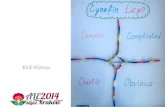

3.1 Characterisation of Cynefin outcomes 12

3.2 Added value 15

4 Learning 18

4.1 Introduction 18

4.2 Ways of working 18

4.2.1. Community level 19

4.2.2. Local service provider level 30

4.2.3. National level 38

4.2.4. The monitoring and learning process 41

4.3 Common barriers to Cynefin ways of working 46

4.4 What needs to be in place to support ways of working developed in Cynefin? 48

4.4.1. Community level – enabling PCs to work differently 49

4.4.2. Local service provider level - values and behaviours 53

4.4.3. National level 59

4.4.4. Aptitudes and competencies for PC facilitator roles 61

4.4.5. Monitoring and learning to support programme effectiveness 63

5 Conclusions and Implications 65

Acknowledgements

The research team thanks all those who gave up time to take part in the quarterly interviews and research workshops, to the PCs both for their time and responding to requests for information, and the Welsh Government management team for their constructive involvement in developing the evidence. All interpretation and views in this report are those of the Brook Lyndhurst authors.

© Brook Lyndhurst 2015

This report has been produced by Brook Lyndhurst Ltd under/as part of a contract placed by the Welsh Government. Any views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the Welsh Government Brook Lyndhurst warrants that all reasonable skill and care has been used in preparing this report. Notwithstanding this warranty, Brook Lyndhurst shall not be under any liability for loss of profit, business, revenues or any special indirect or consequential damage of any nature whatsoever or loss of anticipated saving or for any increased costs sustained by the client or his or her servants or agents arising in any way whether directly or indirectly as a result of reliance on this report or of any error or defect in this report.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

i

Executive Summary

Cynefin is a Welsh Government programme running from April 2013 to March 2016 which

was set up to test and learn about new ways for government at all levels to work in and with

local communities. It operated according to the principles of being led by place-centred

priorities and facilitating more joined-up collaborative working.

The programme design took on board learning from previous Welsh Government

community development programmes and research which suggested that co-ordinated

working between different agencies and programmes at local level, combined with stronger

community involvement in identifying and setting priorities, could potentially avoid

duplication, achieve multiple benefits and more durable long-term outcomes. This called for

an approach centred on place rather than individual policy domains.

The programme turned out to be a timely ‘lab’ for developing lessons that will be relevant to

public bodies as they get to grips with their responsibilities under the Well-being of Future

Generations Wales Act. This report presents the collated findings from the external

monitoring and learning programme which ran five waves of qualitative research and other

evidence gathering during the programme.

The ‘new ways of working’ in Cynefin revolved around initially nine, and eventually eleven,

Place Co-ordinators (PCs) who were locally based facilitators tasked with helping

communities and organisations to work together to improve local places. The PCs were

based in Anglesey, Cardiff, Llanelli, Merthyr Tydfil, Neath Port Talbot, Newport, Rhondda

Cynon Taff, Swansea, Wrexham, Tredegar and Llandrindod Wells.

The role of Place Co-ordinators was to help communities to tackle problems in their local

environment and to make the most of its assets and opportunities, often starting with

immediate issues but with a view to developing sustained involvement and long term

community resilience. PCs were expected to break down barriers and to forge effective

working links between communities and a wide range of agencies and service deliverers in

their area, to improve the effectiveness, efficiency and value for money of public services

and support for communities. The programme also sought to demonstrate practical ways in

which communities can be involved in the decision making processes that affect their

environment and that govern the services provided to them.

Key points of difference from conventional programmes included there being no delivery

budget apart from the PC resource, no pre-set outcome targets or metrics, and an explicit

intention to cut across delivery silos and policy domains. Cynefin’s broad unifying objective

was to facilitate ‘better places’, where public bodies are more attuned to community

priorities and where joined-up working achieves more for people in those communities.

PCs facilitated the development of 59 workstreams around locally determined priorities

together with the community interests and service providers who chose to get involved. The

focus of workstreams and the outcomes from them was very diverse, reflecting the space

PCs were given to catalyse activities around place-centred priorities.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

ii

Workstreams spanned a broad range of place issues, both immediate and long term: local

environment quality, access to greenspace, flooding resilience, poverty, health, housing,

tourism, heritage, arts, youth involvement, economic development, education, training,

renewable energy, and more. Many workstreams were targeted at achieving multiple

benefits across different policy areas, and often for a range of individuals and groups in the

community at the same time.

Most of the important early outcomes were qualitative, in terms of impacts on processes or

‘ways of working’, including building relationships and coalitions of interest to support long

term change. Some of these process changes promise to deliver more substantive benefits

for people and physical environments as workstreams evolve.

Broad quantitative indicators1 suggest that Cynefin-linked activities helped establish 200

new working groups, networks and partnerships; actively engaged individuals and

organisations on more than 6,000 occasions; secured over 23,000 hours of time for Cynefin-

linked activities from individuals and organisations (including public sector bodies); unlocked

over £1.48 million of funding (mainly grants from major charitable and social funds); and

enabled over 900 community members and professionals to receive mentoring and training.

So far, however, change has not been transformational on a widespread scale, although in a

number of places mechanisms have been set in train that have the potential to lead to

radical outcomes if they are sustained once the Cynefin PC is withdrawn. These include

leading examples of service providers working alongside community ‘interests’ (formal or

informal groups and individual residents) and of joint-working between providers to prevent

duplication and to enhance the value of what they are doing already.

The importance of many of the micro-level changes that Cynefin facilitated also needs to be

acknowledged. Some of these micro-level outcomes already are, or could be, building blocks

towards sustained community involvement and/or process change in how public bodies

operate; others relate to intractable local problems that mean a great deal to people locally

but may not get the attention of other initiatives because they are too small or ‘off-target’.

Overall, Cynefin is reported to be adding value by helping to improve service providers’

understanding of what communities want and are capable of, to improve the quality of

dialogue, and to help navigate round blockages embedded in ‘the system’. Many of the

workstreams involve working across traditional policy domains to unlock opportunities

and/or create multiple benefits (e.g. health and greenspace, youth involvement and housing

regeneration).

Cynefin is also helping individuals in communities and service providers to take risks to

‘shake up’ existing practices; in some cases PCs are acting as a ‘community conscience’,

nudging service providers to carry through on promises made or reminding them to involve

residents and communities in meaningful ways; and PCs are brokering relationships between

service providers which result in more collaborative approaches and overcome siloed

working.

1 Quantitative indicators do not do justice to the diversity, complexity and interdependence of the outcomes from Cynefin and were therefore not a core part of the evidence base for outcomes from Cynefin. They are not precise measures of impact and need to be viewed alongside the detailed qualitative accounts of ways of working and related outcomes in chapter 4 of this report.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

iii

Cynefin is able to do this because of the way in which the PC role was defined and because

of the location of PCs as independent operators in the space between communities and

services providers. Key features that appear to underpin effectiveness in the ways of

working adopted in Cynefin were:

Priorities established through co-development of a place-centred understanding of

the local context rather than targets being pre-set by policy priorities or ‘expert’

evaluations of ‘need’;

Space and freedom for a PC (or equivalent facilitator) to be responsive to place and

context;

Sufficient flexibility to be able to respond to evolving circumstances and longer term

change;

Permission to challenge the status quo and to roam across public sector silos;

Independence from specific programmes or vested interests but with Welsh

Government backing;

Continuity of presence in the community and stability in policy and funding in

recognition of the organic nature of the processes and the time needed to build

effective relationships and coalitions of interest;

Good communication mechanisms to support legitimacy and effective ways to share

learning;

Trusting, responsive and constructively critical management

The management team also worked in innovative ways with a much more porous boundary

and collaborative working between the Welsh Government and management contractor

(Severn Wye Energy Agency) than is usual. This was seen to enhance information flows and

the ability to support the diverse needs of the PCs by having a combined pool of knowledge

and contacts to call upon. The management team also felt that a similarly open and

collaborative relationship with the research contractor enabled effective ‘sense-checking’ as

the programme developed.

As well as supporting the work of the PCs at local level, the management team (WG and

SWEA) engaged with stakeholders at all levels and in national government to build an

understanding of collaborative place-centred working and its potential benefits, especially in

the context of restraint on public spending. The rapid feedback loops in the monitoring and

learning process was reported to be effective in supporting that objective with timely

evidence. Stakeholder feedback suggests however that the constituency of support for these

new ways of working is still narrow in government and national bodies. Feedback from

stakeholders tended to be more positive the closer they were to Cynefin activities and was

either more critical or uncertain the more distant stakeholders were.

The research has shown how Cynefin exemplified many of the principles of the Wellbeing of

Future Generations Wales Act (WFG), notably the principles of involvement, collaboration

and building platforms for durable, long term outcomes. The conclusions to this report

therefore summarise key considerations that would need to be addressed by any

organisation wishing to adopt and adapt the learning from Cynefin. These considerations

focus on:

Designing in the space and conditions that underpin effectiveness

Institutional structures, cultures and behaviours

Aptitudes and competencies of individuals

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

iv

The role of national government

Key design features that made Cynefin ways of working effective were listed above. Cutting

across all of those features was a consensus that freedom from externally pre-determined

targets and having unbounded time to build mutual understanding, a local mandate,

relationships and momentum were of critical importance.

Many of the opportunities or levers that were acted upon would have been difficult to

foresee at the start of the process – which led several PCs to warn against any temptation to

create ‘off-the-shelf’ templates for ‘doing’ Cynefin.

Some interviewees also cautioned that longer term funding for facilitator roles (i.e. more

than 1-2 years) is needed to support long-term change processes. While community capacity

has been enhanced by Cynefin, some PCs and local stakeholders alike felt there would

always be a need for a PC, or some equivalent, to catalyse activity, act as neutral broker and

maintain relationships. The gap left by the end of Cynefin in March 2016 could potentially be

taken on by other organisations locally but there is little evidence of that happening yet. The

requirements of the WFG Act may provide a framework for this to happen.

Regarding the second consideration, the research identified blocking behaviours by

stakeholders, together with institutional cultures and practice, as the key barrier to the

effectiveness of collaborative place-based working. Lack of trust in the capability of

communities and a “we know best” attitude in some parts of Wales’ public sector is a major

challenge for place-centred working to address. Some PCs and stakeholders felt there

needed to be more consistent support for collaborative place-based working from Local

Authority chief executives and senior levels in the new Public Service Boards in particular.

There were some pointers towards the types of positive behaviours that are essential to

these novel ways of working, including: individuals in organisations being willing to let go the

exclusive control of agendas; willingness to compromise and willingness to share credit for

outcomes; openness to others delivering on your behalf; and openness to learning and

critiquing your own organisation’s practices. Government being able to give permission to

take risks within the ‘system’ of public services is a big challenge that will need to be tackled

head-on.

Thirdly, a demanding set of competencies is implicated for those occupying ‘facilitator’ job

roles of the kind tested in Cynefin, especially where facilitation is targeted at more strategic

level change. The competencies tend to stretch beyond those typically needed for delivering

conventional programmes.

Competencies can be summarised as a need to be: confident and flexible in conditions of

uncertainty; self-directed and resilient; persistent and creative; diplomatic; opportunistic

and resourceful; and analytical and authoritative. Individuals in these roles also need to be

able to be a conductor, challenger, broker and negotiator and – above all – be willing to take

risks and have “stupid amounts of confidence” (as one PC put it).

The findings in relation to competencies have implications for recruitment processes and job

roles, which may require further reflection on how traditional processes for recruiting

programme or development officers in public sector organisations can be adapted. This

applies equally to local ‘facilitators’ (if and where this model is adopted) and their managers.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

v

The final and determining feature that needs to be in place is high level support from Welsh

Government. The Wellbeing of Future Generations Act provides an opportunity for public

bodies to switch focus to more systemic ways of working in the pursuit of sustainable

development, but it is by no means certain that the learning from Cynefin will be taken up

widely. The Cynefin programme itself is about to end, which does not send a message of

confidence and may well put some of its early achievements at risk.

The research suggests that more will need to be done at all levels of government to secure

buy-in to these kinds of ways of working if Welsh Government wishes collaborative place-

centred working to be adopted more widely, and for it to be done well. It will most likely

need a ‘home’ and champion at the centre, together with governance mechanisms which

encourage compliance but equally maintain the freedoms and independence needed to

make it work effectively.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

1

1 Introduction

1.1 Background The Cynefin programme originated from concerns at high-level in Welsh Government (WG)

that people living in urban areas often experience the poorest environments and lack the

means to influence and collectively tackle the inequalities they face. Starting in 2011, officers

drew on learning from other WG programmes, and research on place-based and

collaborative ways of working, to explore the merits of piloting an innovative approach to

working in, with, and for poor communities by adopting a place-centred approach.

Existing community development programmes were known to be delivering benefits but

they were not seen to be creating transformational or durable change. The research

evidence suggested that co-ordinated working between different agencies and programmes

at local level, combined with stronger community involvement in identifying and setting

priorities, could potentially achieve more and avoid duplication.

Building from the evidence and further consultation in and outside Welsh Government, a

pilot programme was designed to explore what outcomes could be achieved from taking a

place-centred approach, which would not be aligned to any specific delivery programme or

service stream, and would be inspired by priorities identified locally rather than from above.

The Cynefin change progamme ran in disadvantaged communities across Wales from April

2013 and will end in March 2016. The programme employed a local facilitator, or ‘Place

Coordinator’ (PC), to work in each of the following areas:

Anglesey (Newborough and Seiriol ward);

Cardiff (Cathays, Plasnewydd and Adamsdown);

Llanelli;

Merthyr Tydfil;

Neath Port Talbot (Neath town centre, Melin and the Fairyland estate);

Newport (Maindee);

Rhondda Cynon Taff (Treherbert and Blaenllechau);

Swansea (Blaenymaes and Penderry wards);

Wrexham (Caia Park and Cefn Mawr);

Tredegar; and

Llandrindod Wells.

1.2 Aims of the Cynefin change programme Ambitious aims were set for Cynefin. It was intended to be far more than a community

capacity building programme that enables community groups to develop and run projects,

or a delivery programme with some community engagement. A core aspiration was to

facilitate greater co-ordination among the various agencies and authorities that are working

locally, to add value to what communities want and are able to do. This was to be a key

measure of the success of the programme.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

2

The aims of the programme were originally framed around outcomes in three spheres:

PLACE: building on people’s sense of pride in place and environments, communities

are strengthened and quality of life gains are maximised in places where there is

poverty.

PROCESSES: new processes are developed through which people can identify and

negotiate shared priorities for places where they live and work and draw down the

support they need from government and other agencies.

POLICY: there is more joined-up working and thinking, so that policy makers and

delivery agents at all levels hear, understand and respond more precisely to the

identified needs of local places and people.

Translated into practical terms, this meant that the Place Coordinator's job was to help

communities to tackle problems in their local environment and to make the most of its

assets and opportunities. The immediate focus of much of the PCs’ work was on local issues

of poverty and inequality: for example poor local environment quality, little or no access to

green space, fly-tipping, the threat of flooding, fuel poverty, the need for local growing

spaces etc. This kind of action was intended to lead as well to more active involvement by

residents in the longer term development of local ‘green growth’ and resilience, for example

in developing community energy generation or other social enterprise activity. On that

basis, each of the 11 PCs co-developed with their communities a range of ‘workstreams’

each focused on a locally identified problem/opportunity.

Place Coordinators were expected to focus on removing barriers to action and forging

effective working links between communities and a wide range of agencies and service

deliverers in their area. Better co-ordination of service offerings within communities was

expected to improve their effectiveness, efficiency and value for money, and to deliver

multiple benefits for residents and local businesses. PCs had no delivery budget of their own

so they had to devise and enact ways to secure the necessary resources and financial

support.

Important aspects of the work included raising communities’ capacity and resilience by

helping to lever funding into the communities from a wide range of sources, bringing

support and guidance to community groups and social enterprises, helping people to use

local assets for community benefit, generating income and developing skills and training

opportunities.

The programme also sought to demonstrate practical ways in which communities can be

involved in the decision making processes that affect their environment and that govern the

services provided to them.

Parallel influencing work was undertaken by the Cynefin management team at national level

to build support from key stakeholders for new ways of thinking and working at local level.

The research base had also identified how ‘co-production’ approaches of this kind tend to

challenge existing institutional cultures and ways of working so there was a need to capture

learning about the way in which practices responded to these anticipated challenges and

what makes place-centred working effective.

Chapter 2 describes in more detail how the programme was organised and operated.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

3

1.3 Monitoring & Learning Methodology The Welsh Government wanted to set up a formative monitoring and learning (M&L)

process to run throughout the duration of the programme, so that early insights could be

used to shape the programme as it progressed. This was especially important in the context

of the work being done to develop the Wellbeing of Future Generations Wales bill (FGW),

where longer term thinking and joined-up working between public sector organisations had

been identified as core to the principle of sustainable development and the duty to be

placed on the public sector to implement it.

Development of the monitoring and learning framework

The innovative approach being taken in Cynefin meant that standard monitoring and

evaluation approaches could not simply be adopted to generate the kind of evidence-based

learning that was needed.

In particular, it was clear that the typical approaches used in impact or process evaluations

would not generate the breadth and depth of learning that WG needed. The fact that

Cynefin could not claim to ‘own’ the outcomes outright (because it was facilitating others to

do things) meant that standard ways to measure or attribute impact were not meaningful.

Moreover, the intangibility of many of the outcomes – notably community empowerment,

new ways of working, relationships and organisational behaviours – meant that focusing on

quantitative measures could lead to a superficial account of programme outcomes. A review

of evidence from innovative approaches elsewhere had identified significant gaps in the

evidence about how they had worked, even where process evaluations had been

undertaken, and this was a key factor which informed the design of the M&L approach to

Cynefin.

Taking into account those and many similar considerations, a monitoring and learning

framework was co-designed during the early stages of the programme by the research team

(Brook Lyndhurst) and the Welsh Government management team, with involvement from

the Place Co-ordinators and ‘early learning’ interviews with some of the local and national

stakeholders who had been involved from the start.

The agreed approach was to develop a rich narrative account of Cynefin based mainly on

qualitative evidence and case examples, supported by a set of 11 cross-cutting indicators

that would cover a mix of place and process outcomes (see Annex 2). The feasibility of

developing quantitative RBA-type2 indicators for every local workstream and Cynefin overall

had been explored in detail (including consultation and the creation of draft indicators) but it

was decided by all involved that a mainly qualitative approach would be a more productive

use of research and Place Co-ordinator resources. This design process in itself was an

example of Cynefin ways of working, including flexibility and responsiveness.

2 Results Based Accounting, which is a trade-marked evaluation methodology used in Welsh

Government, notably by Communities First.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

4

The research questions

The framework comprised a set of research questions and a suite of data gathering

approaches to generate evidence to answer the questions. The agreed research questions

related directly to the framing of objectives around place, process and policy as set out

above and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Research questions in the Cynefin monitoring and learning framework

Research questions

1. What approaches and ways of working have been adopted in Cynefin? And how do these differ from conventional models of service delivery?

2. What have been the barriers and facilitators to these new approaches and ways of working?

3. What are the key lessons from Cynefin about how the Welsh Government, local government and other agencies delivering services in communities?

4a. What outcomes has Cynefin achieved in improving places?

4b. What outcomes has Cynefin achieved in improving processes?

4c. What outcomes has Cynefin achieved in improving policies?

5. Are these outcomes durable over time and in keeping with the principles of Sustainable Development?

During the course of the Cynefin programme, it became increasingly clear that overlaps

between outcomes in the place-process-policy ‘spheres’ often make it difficult or

nonsensical to talk about them separately. This observation has influenced the way in which

outcomes are characterised in chapter 3 and explored in further detail in chapter 4. As the

learning developed it became clear that it is more logical to describe Cynefin outcomes as an

integral part of the narrative about ways of working, because many of the place and process

outcomes in particular are interdependent. It also became clear that it is more logical to

differentiate between Cynefin outcomes at three different levels:

for people in communities;

at the level of organisations working at or influencing outcomes at local level;

and at national level, including Welsh Government and higher tiers of organisations

that also operate locally

While place, process and policy are common themes throughout the narrative in the report

the detailed findings in chapter 4 are structured around the three levels above,

acknowledging that there is overlap between them.

Data and evidence methods

The monitoring and learning research ran throughout the duration of the Cynefin

programme. The main feature was quarterly waves of qualitative research interviews with

PCs, stakeholders and the management team, plus the compilation of cross-cutting

indicators from data supplied by the Place Co-ordinators3. These and other tasks are

described in Figure 1. The first wave of research, together with PC’s own initial scoping work,

provided the qualitative ‘baseline’ against which progress was assessed: this was

3 It was agreed that this data would not be verified independently by the research team although ‘sense checks’ were undertaken and queries resolved with the relevant PC.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

5

incorporated into a developing narrative about workstream ‘journeys’ rather than a

before/after comparison of change in narrowly defined indicators.

At the end of each quarter, evidence from those various sources was brought together and

shared with the Welsh Government management team so that it could be used in their on-

going guidance to the PCs and engagement with policy makers.The management team

identified areas for immediate action from the emerging research findings, such as

engagement activity with specific stakeholders or additional training for PCs. Emerging

learning was also fed back to the programme’s Advisory Group each quarter for a ‘sense

check’ on how Cynefin was being delivered. Feedback from WG in response to the emerging

findings and input from the Advisory Group was then incorporated into the next wave of

research. The findings in this final report were developed from all of the evidence gathered

during the monitoring and learning process.

Figure 1 – Evidence approach in the Cynefin monitoring and learning framework

Note: Blue boxes indicate work by the research team, green boxes denote individual PC activities from which the research team collated evidence

across the programme; evidence in purple boxes was jointly developed.

Wave 1 Wave 2 Wave 3 Wave 4 Wave 5

InterviewsPCs, WG,

stakeholders

InterviewsPCs, WG,

stakeholders

InterviewsPCs, WG,

stakeholders

InterviewsPCs, WG,

stakeholders

InterviewsPCs, WG,

stakeholders

Workstream/stakeholder

maps

PC workstreamPen portraits

PC workstreamPen portraits

PC workstreamPen portraits

Workstreamjourneys

Stakeholder survey

Stakeholder survey

X-cutting indicators

X-cutting indicators

X-cutting indicators

X-cutting indicators

X-cutting indicators

PC learning diaries

Next wave

WG

PCs

Next wave

WG

PCs

Next wave

WG

PCs

Next wave

WG

PCs

Final report

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

6

Limitations of the evidence

The evidence is largely drawn from qualitative methods. While the approach taken followed

social science best practice for qualitative approaches, the evidence is subject to the usual

limitations of that method. The evidence comes from self-reported accounts and relies on

there being accurate and unbiased recollection from informants. The risk of bias from self-

interested responses was taken into account by eliciting views from a wide range of

perspectives, including those less closely involved in Cynefin and from some known to have

critical views. Checks were also built into the analysis process (e.g. through triangulation of

evidence sources and team workshops to moderate emerging findings) to mitigate the risk

of bias.

Other limitations apply to numerical data shown in the report, namely the cross-cutting

indicators and the stakeholder survey. The cross-cutting indicators were compiled from data

provided by PCs and, while sense checks were applied, the research team did not verify the

data independently through further local research. The indicators should be seen as

indicative of the scope and scale of outcomes and not as precise accounts of impact. The

resource available for the stakeholder survey meant that the sample was derived from

contacts provided by the PCs and the management team (i.e. it was a convenience sample

rather than a random or stratified representative sample). The data has therefore been

interpreted qualitatively and in the context that it may not represent the views of those less

involved in Cynefin activities.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

7

2 Programme description

This chapter provides a high-level description of how Cynefin operates. This provides the

essential context for the findings on outcomes and learning that are presented in chapters 3

and 4, especially for those readers unfamiliar with the programme and the ways in which it

differs from a traditional programme delivered in communities.

2.1 Structure of the programme Figure 1 summarises some of the key differences between Cynefin and a traditional

programme that is supporting or working in communities.

Figure 2 – Distinctive features of Cynefin compared to a traditional programme

The ‘new way of working’ revolved around initially 9, and eventually 11, Place Co-ordinators

who were the locally based facilitators that were tasked with bringing communities and

organisations together to improve local places. They were hosted by local authorities or

national organisations in their local offices (see table 2 in section 2.2 which gives more detail

about the PCs and how their roles differed from conventional approaches).

Management of the PCs and programme delivery was sub-contracted to Severn Wye Energy

Agency (SWEA) which had previously been involved in the Welsh Government Pathfinders

programme to support community climate change initiatives. There was also a programme

officer in Welsh Government. In practice, and in keeping with the principles of Cynefin, the

internal and external managers worked closely together as a team of two, rather than in a

traditional client-contractor relationship (as discussed further in chapter 4).

Governance mechanisms are shown in Figure 3 below. Ultimate responsibility for the

Cynefin change programme lies with the Minister for Natural Resources. However, there are

a few layers of governance that advise and shape this change programme.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

8

Cynefin Advisory Group

The Cynefin Advisory Group focuses on creating a dialogue between public service delivery

agents, local authority partners and policy leads from across the Welsh Government. The

role of the Advisory Group is to explore policy and delivery links, identify gaps or challenges

and consider the work being undertaken by the Place Coordinators in the context of policy

development.

Place Development Leadership Group

The Place Development Leadership Group, chaired by the Commissioner for Sustainable

Futures Peter Davies, has a wider remit to look at place based working as a whole across

Wales. The Group has more of an academic focus, and looks at emergent and ongoing

research in the field of place based working. While being a Wales-wide expert forum for

place based work, the Group also acts as a senior advisory group to Cynefin.

Place-based working seminars

Half-yearly place-based working seminars bring together practitioners from across the Welsh

public, private and third sectors to share ideas and best practice, participate in collaborative

workshops and identify opportunities to work together across work streams.

Figure 3 – Governance map

Programmes Engagement & Delivery Board (Welsh Government)

Cynefin Change Programme

WG Place Programme – Governance Map

Minister for Natural Resources

Place Programme

Advisory Group

Linking up across WG Policy & other initiatives

PLACE 2

PLACE 3

PLACE 4

PLACE 5

PLACE 6

PLACE 6+

PLACE 1

eg. Newport

Local

Stakeholder

Group

gp

gp

gp

gp

gp

gp

gp

Advisory Group

WG Prog Team

Place Manager

Place Co-ordinators

Operations Group

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

9

2.2 The Place Co-ordinators Cynefin currently employs 11 Place Coordinators (PCs) in different locations across Wales

(until March 2016). These PCs did not all start working at the same time. The first nine took

up their posts between March and September 2013 . Two more were appointed in February

2015. For this reason the majority of the M&L research has focused on the original nine PCs.

As noted above, Severn Wye Energy Agency (SWEA) was contracted to manage the Cynefin

programme, and employs eight of the 11 PCs directly. The three other PCs are employed by

partner organisations Environment Wales, Keep Wales Tidy (KWT), and Natural Resources

Wales (NRW). Table 2 below identifies where the 11 PCs were located and summarises the

key foci of their workstreams. Further details of the 57 individual workstreams that PCs have

undertaken are given in Annex 1.

Table 2 – Introduction to the Place Co-ordinators

Location Host Work focused on…

Llanelli Carmarthenshire

County Council

… co-creating a community owned emergency plan for Llanelli;

developing an ethos of co-operation and co-production between service

providers that will add value to current areas of work and lead to a

different way of working; and facilitating the response of Llanelli Town

Council and the local community to the Well-being and Future

Generations Bill (now Act)

Wrexham Wrexham

County Council

… supporting local communities and organisations in the Cefn Mawr

and Caia Park areas of Wrexham through capacity building, tourism and

timebanking; and promoting community renewable energy across

Wrexham

Rhondda

Cynon Taff

(RCT)

Rhondda Cynon

Taff County

Council

… facilitating improved access to woodlands for local communities;

supporting the creation of tourism hubs across the county and a

community flooding group; and, at a more strategic level, facilitating the

adoption of more co-productive place-based working by service

providers

Neath Port

Talbot

(NPT)

Keep Wales Tidy …place planning for local target areas, bringing residents and service

providers together to improve the local environment and resources;

helping social landlord NPT Homes with its place planning work;

facilitating an increase in community cohesion and capacity, with a

particular focus on young people

Cardiff Cardiff City

Council

… to create and sustain a sense of community in an area of Cardiff

(Cathays) which has a highly transient population by catalysing

community-led activities to reduce littering, improve local

environmental quality, promote more active travel, and celebrate local

food production

Anglesey Groundwork

North Wales

… stimulating community participation in service design and delivery;

and enabling local communities to access funding and new

opportunities to undertake activities that benefit the local environment

and economy

Merthyr

Tydfil

Flytipping Action

Wales

…bringing stakeholders together to improve open spaces in Merthyr to

encourage greater use of these assets by the community, as a resource

for health and wellbeing through GP referrals to local activity groups

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

10

Newport Newport City

Council

… facilitating the improvements of the Maindee area of Newport, by

encouraging residents and businesses to find and lead opportunities to

develop a more sustainable and resilient community

Swansea Swansea City

Council

… bringing stakeholders and service providers together to improve

provision and end duplication, recognising that Swansea already has a

lot of community groups, networks and support systems in place

Llandrindod

Wells

Powys County

Council

… stimulating community-led activities, engaging with local

organisations and businesses to promote tourism in Llandrindod and the

surrounding area, and making initial linkages with service providers at a

more strategic level

Tredegar Tredegar Town

Council

… undertaking engagement work with the local community to

understand their needs and desires, joining up stakeholders and taking

forward projects on a wide range of issues including food, energy, social

enterprise and local business support.

The ways in which the PCs were enabled to operate was very different from normal

‘development officer’ roles. Since it would have contradicted the place-centred approach

that was being explored, the Cynefin programme did not set specific and measurable targets

that were common across all the areas in which it worked. The PCs therefore had no pre-

determined targets or workstreams, or target audiences, at the outset of the programme.

Instead, the PCs’ first task was to ‘baseline’ the area to which they had been assigned – to

explore what was already happening under the broad umbrella of ‘place improvement’, and

to identify opportunities where they could facilitate connections within and between

communities, service providers, policy and other stakeholders to add value to current ways

of working. At its most basic, the intention was that PCs would be ‘facilitators’ and ‘catalysts’

rather than ‘deliverers’.

The initial place planning process was a distinctive feature of Cynefin. It consciously avoided

a ‘task and finish’ approach – namely one based on one-off community consultation

meetings at the start, technical analysis and a written report and action plan. Instead, PCs

were required to spend time building a vision, a mandate and shared plan with individuals,

community groups and stakeholders over an extended period. This, often iterative, process

was expected to bottom out the real causes of local issues, including how systemic factors

(e.g. assets, institutions, stakeholders, policies, people) interact to create blockages or

opportunities for change. Variability of approaches was therefore an inherent part of the

design of the programme, enabling WG to learn how different approaches led to different

outcomes and what needed to be in place to make them work.

Place-centred priorities were identified during a scoping period through events such as

stakeholder workshops and community visioning events, individual conversations with

groups and stakeholders, from previous and existing research, or suggested by PCs from

their previous or other roles in their areas (particularly in the case of those PCs ‘seconded’

from other organisations). The detail of workstreams was worked up by PCs with the

management team and with the agreement of key stakeholders. Once priorities had been

identified and workstreams defined, performance targets and milestones were negotiated

between PCs and the management team, which were then monitored as the workstreams

developed. The way in which these performance standards were defined, however, still

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

11

enabled considerable latitude in how PCs operated, so that the PCs could be responsive to

evolving circumstances and relationships as their workstreams took shape.

Another distinctive feature was that the PCs had no budget other than their own time4 so

that a key part of their role was to influence others to use existing resources and budgets. In

several cases, PCs also helped community organisations to secure funding from major grant

funders (perhaps more like traditional development officers) although funding was quite

often sought to support process changes rather than to fund specific community activities.

Chapter 4 reports in detail on the learning about how Cynefin ways of working were and

were not effective, and how they compared to usual practice.

4 Although later in the programme PCs were able to apply for very small grants to help fund some

small-scale activities.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

12

3 Outcomes – headline findings

Given the nature of Cynefin – its broad aims, operation, and the diversity of the PCs’

locations and workstreams – the outcomes it has achieved to date have been highly varied.

This is true on several dimensions: with respect to scale, from the micro-local to the more

strategic within a place; in relation to who has or will benefit; and whether outcomes were

time-bound or contributed to a continuing change process.

It is also possible to map outcomes broadly onto the place-process-policy axes envisaged in

the original programme design, although atomising outcomes in this way tends to miss their

interconnected nature and their link to place contexts (as noted in section 1.2). This section

therefore provides a headline summary of the key types of outcome from Cynefin under the

the three headings before these are unpacked in greater detail and illustrated through

workstream ‘journeys’ in chapter 4. The second part of this chapter reports the feedback

from stakeholders interviewed in the research on their perceptions of the value added of

Cynefin. This is again at headline level before it is explored in further detail in chapter 4.

3.1 Characterisation of Cynefin outcomes According to the cross-cutting indicators for which PCs provided data throughout the

monitoring and learning programme, by mid-2015 Cynefin had: catalysed 59 workstreams

and over 200 new working groups, networks and partnerships; actively engaged individuals

and organisations on more than 6,000 occasions; secured over 23,000 hours of time for

Cynefin-linked activities from individuals and organisations (including public sector bodies);

unlocked over £1.48 million of funding (mainly grants from major charitable and social

funds); and enabled over 900 community members and professionals to receive mentoring

and training.5

The breadth and diversity of Cynefin outcomes reflects the space that PCs were given to

build their workstreams around place-centred priorities. Outcomes spanned local

environment quality, access to greenspace, flooding resilience, poverty, health, housing,

tourism, heritage, arts, youth involvement, economic development, education, training,

renewable energy, and more. Many workstreams were targeted at achieving multiple

benefits, and often for a range of individuals and groups in the community at the same time.

While it is therefore difficult to characterise outcomes in a simple way, examples of some of

the main thematic outcomes are identified in table 3 around the place-process-policy

headings and these are discussed further in chapter 4.

5 These indicators should be seen as illustrative of the scale of Cynefin involvement rather than

precise figures: the overlapping nature of the work with other programmes means in particular that it is difficult to attribute outcomes specifically to Cynefin and the diversity of PC’s activities meant that figures reported under given indicators may be qualitatively different. The indicators are as reported by the PCs and were not verified independently. The full set is shown in Annex 2.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

13

Table 3 Characterisation and examples of Cynefin outputs and outcomes

Physical/tangible outcomes such as…(examples in bullet points)

Physical improvements to place

Installation of community waymarking signs in Cardiff to increase awareness and usage of local

amenities and businesses, and to encourage more active travel (walking/cycling) in the

community.

Clean-up of areas repeatedly affected by fly-tipping in Merthyr led by key stakeholders (Local

Authority, housing association and landowner) and with involvement from the community.

Helping communities to access funding

A PC supported a successful bid for £365,000 of Arts Council funding for significant community-led

regeneration work in Newport which will be on-going.

In Anglesey, the PC brought the community and stakeholders together in a successful bid for

£250,000 of Olympic Legacy funding. The group is now running its own small grants programme

having distributed 21 grants of £1,000 to £2,000 to fund local activities.

Supporting the set up and development of new community groups and organisations

The Wrexham Energy Group, which has undertaken feasibility studies and is working towards

developing a community renewable energy scheme.

In Newport, facilitating the creation of a community group and supporting it to expand its horizons

to become a social enterprise (Maindee Unlimited) which has recently been approached by the

local authority to get involved in local asset improvement, and potentially, ownership.

Protecting and enhancing community assets

The PC in Wrexham helped to support a case to the local authority for continuing funding for a

local development trust while it secured other sources of funding. He then brokered agreement

for the social enterprise to be co-bidders with the local authority for a Big Lottery grant to support

timebanking (outcome pending at the time of writing).

Process/relationship outcomes such as…

Building a shared vision for place

Many of the PCs undertook visioning to identify priorities and opportunities. The PC in Wrexham in

particular used asset mapping to identify existing resources in the community and opportunities to

build from. Visioning is covered in more detail in chapter 4.

Brokering and facilitating new collaborative ways of working

Bringing service providers together to identify overlaps, duplication and opportunities for joint

working in the Penderry Providers Planning Forum in Swansea which has resulted in specific

actions and outcomes (the PC has logged almost 200 ‘deals.’)

Bringing communities and service providers together

Leading a Youth Consultation in Neath Port Talbot which has led to some physical outcomes such

as improvements to playing fields, as well as ongoing engagement between young people and

service providers through creation of a youth council and a Local Authority Youth Liaison Officer.

Acting as an ‘honest broker’ between community groups and a Local Authority to overcome a

historic stalemate and secure a piece of land to be used as a community garden and playing fields

by different interest groups in the community in Wrexham.

Identifying shared/multiple benefits to enable service providers to work together

Facilitating the formation and agreement of shared goals for service providers in Rhondda Cynon

Taff to underpin collaborative working.

Bringing service providers together to deliver health benefits for residents related to greenspace

improvements in Merthyr.

On a smaller scale, combining IT training courses for residents to prevent them being cancelled

because of low attendance.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

14

Policy outcomes such as…

Policy influencing from the ‘bottom up’

Llanelli, where the PC has initiated and facilitated the development of a community-led emergency

plan to complement that of the Town Council, which has now been adopted, with other towns in

the area looking to emulate the idea. The work was identified as best practice by the Wales Audit

Office and the team leading the Wellbeing of Future Generations Wales Bill.

Drawing attention to areas where policy doesn’t work for communities

Newport, where Maindee Unlimited is working with the Local Authority on an asset transfer which

has highlighted barriers to community control and a need to revise the asset transfer policy.

Enabling a community ‘voice’ in policy making

A Llanelli We Want event that communicated the goals of the Well-being of Future Generations

Act to local residents and engaged them to vote on priorities for the future of their area in line

with these goals, which were then adopted by the Town Council.

Complementing national policy implementation

The PC in RCT was approached by NRW for advice about place-based working and access to

contacts with respect to its piloting of Area-Based Planning, having recognised that the PC had a

good overview and cross-cutting relationships that NRW could build on.

Engaging with and supporting national policy development and programmes

As a result of its efforts to make links across policy areas, the management team was invited to

share Cynefin learning with policy teams working on new Welsh Government Bills or initiatives.

This included NRW in relation to the Environment Bill and area-based planning pilots they are

currently running, the team responsible for the Well-being of Future Generations Bill (now Act),

and Public Health Wales concerning a multi-service provider initiative being developed for the

Health goal in the WBFG (see section 4.2.3).

National level outreach work by the management team has also taken Cynefin learning to other

public and charitable programmes (e.g. Big Lottery).

By the end of the M&L research, it was apparent that many of the Cynefin workstreams had

made significant headway in achieving process improvements but many were yet to deliver

large scale tangible place improvements. Influence on local and national policy was limited

to a few leading examples. There was as yet no widespread evidence of transformational

change although in a number of places mechanisms had been set in train that have the

potential to lead to radical outcomes if they are sustained once the Cynefin PC is withdrawn

(see further discussion on durability and supporting conditions in chapter 4).

Cynefin had also resulted in the demonstration of innovative models that could have the

potential to be rolled out elsewhere: for example the Penderry Providers’ Planning Forum,

the collaborative service provider model in RCT, the health workstream in Merthyr to link

greenspace and exercise referral, and the approach to co-productive working between

communities and town council in Llanelli (see the annex for a summary of all PCs’

workstreams).

While some of the potential outcomes of Cynefin lie in the future, there were tangible

benefits for people in communities during the time it was in operation. In general, the scale

of outcomes has tended towards the micro level (i.e. at ward level rather than across a Local

Authority or area), although there were more strategic ones, as the examples above

illustrate. This is not to negate the impact of Cynefin, but to recognise that a large

proportion of PCs’ work focused on and occurred at this more micro level. It is also

important to note that the initial short-term funding of Cynefin (for nine months)

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

15

contributed to a focus on achieving immediately tangible outcomes, although most PCs also

initiated activities with a longer term horizon during the early period, which were taken

forward when funding was continued.

Many of Cynefin’s micro-level achievements were, at least superficially, similar to those

typically delivered by development officers, such as training, setting up community groups,

promoting healthy living, tackling local environmental quality and so on. While some could

not be said to be especially different or innovative, in some cases these ‘micro-level’

outcomes were distinctive in that they had required the kind of time, persistence and

challenge across operating silos that may not have been possible to deliver in other

programmes.

Moreover, the way in which they had been prioritised through community involvement

meant that at least some of Cynefin’s micro-level outcomes focused on intractable local

problems that meant a great deal to people locally but may have been by-passed by other

initiatives because they were ‘off-target’ or too resource intensive compared to their

perceived importance . Starting small by tackling these sometimes overlooked but vexing

issues (e.g. broken goalposts, graffiti, open space access) appeared to be a ‘door opener’ for

the wider and sustained place-based work of at least some of the Cynefin workstreams.

Illustrative examples can be found in the case study boxes in chapter 4.

Finally, looking at the level of the programme as a whole, a distinctive feature of outcomes

in Cynefin is the way in which they have cut across diverse policy areas to deliver multiple

benefits, both within some individual workstreams and when outcomes from all the various

workstreams are combined.

3.2 Added value Feedback from stakeholders tended to be more positive the closer they were to Cynefin

activities and was either more critical or uncertain the more distant stakeholders were.

Perceptions did change during the course of the programme, including of some individuals

who had been critical at the beginning. Over time, examples of Cynefin in action

communicated locally and by the management team began to help demystify what the

programme meant by ‘new ways of working’ and what might be achieved. There remain

critical voices, however, including some who think Cynefin is duplicative, expensive, too

micro-local, too unfocused, and not sufficiently disruptive at a strategic level. More detailed

learning about stakeholder perceptions and involvement is provided in the various sections

on local service providers and national level engagement in chapter 4.

A stakeholder survey was carried out in the last wave of research, which elicited 177 detailed

responses6 from stakeholders who had been in contact with the programme to varying

extents and in various roles. Responses (in Figure 4) were largely positive to questions

relating to the perceived value added of Cynefin. This was most true (by a small margin) in

relation to the impact of Cynefin on improving service providers’ ability to engage in

communities.

6 More people answered but did not respond to the key ‘value of Cynefin’ question. It needs to be

noted there was very limited resource for a survey so that measures were not taken to ensure this was a representative sample.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

16

Figure 4 – Stakeholder feedback on the added value of Cynefin

Overall, Cynefin was thought to add value by working across silos, coordinating resources

and catalysing more innovative approaches. Examples of ways in which stakeholders and PCs

reported that Cynefin is doing this included:

Ensuring service providers are more in touch with local community priorities;

Brokering relationships between service providers and communities, including in

situations where relations have become strained;

Joining up disparate interests that would not have come together without a catalyst

(e.g. tourism in Wrexham);

Helping existing local groups to come together, including with service providers, to

grow their ambitions and scale of what they are involved in (e.g. Anglesey, Maindee

in Newport)

Adding an extra resource and dimension to existing programmes (e.g. working with

local Communities First or NRW officers)

Helping communities to develop the capacity, partnerships and vision to secure

large amounts of funding that they would not have been able to do otherwise (e.g.

Newport);

Identifying and preventing duplication between service providers and thus potential

cost saving (e.g. Swansea, RCT);

Identifying opportunities for mutual and multiple benefits from adopting a joint

approach (e.g. health workstream in Merthyr).

While there is a clear sense among stakeholders that Cynefin is adding value through

collaborative working, most respondents were not able to say if Cynefin had impacted on

local or national policy or they stated it had little impact (as Figure 4 shows). Feedback in the

qualitative interviews with local stakeholders confirmed that this isn’t how Cynefin is being

perceived on the ground: it is being seen as a way to get service providers to work in an

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

...the impact of Cynefin in influencing local ornational policy-making

...the extent to which you think Cynefin isadding value to existing service provision

...the impact of Cynefin in improving the abilityof service providers to engage with the local

community

...the impact of Cynefin in empoweringmembers of the community

How would you rate...

5 (Significantimpact/added value)

4

3

2

1 (no impact/addedvalue)

Don't know

No response

Number of respondents (n=177)

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

17

involved way with communities and each other but is not being seen as a vehicle for

influencing policy, even though giving communities a greater voice in local and national

policy was one of the original intentions.

PCs cited some examples of how they had used activity around the WBFG Bill to add impetus

to some of their work but on the whole PCs similarly found it difficult to say how their

workstreams would or could influence policy. While some PCs were well attuned to

opportunities to link their local work with national policy developments not all of them were

as broad in their thinking. This could be an area for development in any future programme

similar to Cynefin.

Equally, a minority of respondents in the survey did perceive that Cynefin was having an

influence on policy, and this was also a view shared by certain national stakeholder

interviewees. At this level, and largely through the activities of the management team,

Cynefin was seen to be using learning generated locally by PCs to start to inform policy

development within some areas of Welsh Government or within other national delivery

bodies (see section 4.2.3). Local communities and PCs were not necessarily fully aware of

this national-level activity, which may partly explain the survey results.

The following chapter explores some of the headline themes identified in this chapter in

more detail.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

18

4 Learning

4.1 Introduction This chapter explores learning about the Cynefin ways of working and their related

outcomes in more detail and more narratively, including case examples and workstream

journeys to illustrate how different facets of PCs’ approaches joined up to make them

effective. This is followed by a summary of the barriers that were commonly seen and,

conversely, factors that were reported to be enabling. The last part of the chapter considers

what kinds of operating arrangements and behaviours are implicated in ‘what needs to be in

place’ to enable Cynefin-style approaches to operate effectively in a public service setting.

4.2 Ways of working One key overarching feature of the ways of working adopted within Cynefin is their diversity.

Cynefin was not designed to implement one pre-determined methodology in every area it

operated but rather to try out and learn from a range of approaches to improving places,

process and policies in Wales. The ways of working adopted by different PCs were also

partly a reflection of the specific characteristics, opportunities and challenges they found in

their area, their personal interpretation of the PC role and the different competencies each

possessed. What has ultimately emerged is that there is no singular “Cynefin way” but

instead a nest of interrelated approaches each with their own pros and cons, and some more

suited to certain local contexts and the capabilities of individual PCs than others7. In

addition, not all of the approaches were radically “new” or different from approaches

already being adopted by officers of other pre-existing programmes and initiatives in Wales.

This section describes and illustrates the different ways of working adopted within Cynefin,

with a particular focus on: how these compare and contrast with existing approaches; how

effective they have been in delivering outcomes and adding value; and why. The section is

loosely structured around the three different levels that Cynefin can be seen to have

operated at:

Community level - residents and community groups

Local service provider level - local authorities, Local Service Boards (LSBs),

Community Voluntary Councils (CVCs), housing associations, other local service

providers, and locally-based arms of national organisations, e.g. Communities First

clusters and NRW officers working locally

National level - national policy makers in the Welsh Government, NRW,

Communities First, etc.

The extent to which Cynefin has facilitated linkages and relationships between these

different levels is also explored.

7 See also section 4.4.4 on PC competencies.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

19

4.2.1. Community level

All of the PCs engaged with residents and community groups in their local area, although in

practice the nature and extent of this engagement did vary somewhat between individual

PCs. For some, particularly those with a professional background in community development

and who interpreted their role mostly in terms of facilitating “grass roots” community-led

activities to improve the local area, this has been their primary focus. Others have generally

divided their time between engaging at this level and at the level of local service providers.

It was generally at this community level that some stakeholders, particularly national ones,

queried whether Cynefin was doing anything genuinely new or different. Local authorities

and some national programmes or initiatives were known (or assumed) to already be

engaging with local communities. From a distance these national stakeholders were

concerned about Cynefin duplicating these efforts and were not conscious of it doing

anything different or adding value. In practice, and drawing in particular on evidence from

local stakeholders who had first-hand exposure to the work of the PC in their area, certain

features of how Cynefin engages with local communities did emerge as being distinct from

more traditional pre-existing approaches to community engagement. These features, and

their perceived added value, are discussed under the following broad headings:

Open-ended engagement and involvement

Building community capacity

Removing blockages

Bringing communities and service providers together

Open-ended engagement and involvement

One of the clearest distinctions local stakeholders made between Cynefin and other

programmes and initiatives was that the initial “dialogue” between the PC and members of

the local community was open-ended. Residents and community groups were generally

invited by the PC to identify local priorities themselves through initial visioning events.

Workstreams were then developed around these priorities. Other PCs, wary of over-

consulting local communities in areas where there had been recent attempts at

consultation, had relied more on one-to-one conversations with residents or groups and

their own research to identify local priorities. Interest in these from the wider community

was then explored through subsequent public events. Whichever of the two approaches

was used, priorities were developed ‘bottom up’ following local scoping and conversations in

the community, from which target outcomes were identified then agreed by Welsh

Government with the PC and key local stakeholders.

These approaches were contrasted by local stakeholders with other forms of community

engagement they were aware of – in which the “priority” and the intended outcomes of any

activities linked to this had already been decided by the programme or initiative doing the

engagement before there was any community involvement. Specifically, several compared

Cynefin with Communities First, saying they felt the latter was too narrowly focused on

specific ‘top down’ outcome targets. Consequently their engagement tended towards

proposing specific activities aligned to these targets and applied to local communities. For

example, one resident who had met with officers from both programmes commented on

how different and “refreshing” it had felt to be asked by the PC what he thought was

important in the local area, and to be listened to.

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

20

Open-ended engagement &

involvement

In Cardiff, the PC ran an initial ‘Community Visioning’ event in which attendees were encouraged to identify key challenges, opportunities and risks for their area. An ‘Ideas Event’ followed which invited the community and other stakeholders to discuss and co-design project ideas relating to the themes that emerged from the visioning event. ‘Scoping Meetings’ were then held to prioritise these ideas before the PC catalysed a number of workstreams to deliver these – eventually resulting in diverse outcomes such as 2 large food festivals in a deprived area, and a 101 metre mural on a frequently vandalised wall. A recent ‘Re-visioning’ saw members of the community celebrating what had been achieved so far, and generating new project ideas.

The reported added value of the more open-ended engagement and involvement practised

through Cynefin included the following:

The development of workstreams that closely reflect the priorities of local

communities. This is partly reflected in the diversity of the workstreams that have

emerged across the different Cynefin areas (see Annex 1) which span such issues as

climate change, waste, art, tourism, health and regeneration. Despite Cynefin not

having pre-determined outcome indicators, there are also clear and significant

overlaps between the intended outcomes of these workstreams and the national

goals of the WFG Bill.

The active involvement of members

of the community. Linked to the

above, PCs have reported that by

engaging communities in this way,

they have been able to make

connections to residents and

community groups early on that

have been invaluable throughout

the course of their work. In one area

for example, some of those

attending initial visioning events

went on, with the support of the PC,

to form a group that has since bid

for and received significant funding

to make improvements to their local

area. Anecdotally at least, some PCs

and local stakeholders also reported

that public events held as part of a

workstream (such as the two food

festivals highlighted above) have

attracted large numbers of local

residents to attend.

In addition, identifying workstreams

that reflect the priorities of the local

community had given PCs a clear ‘mandate’ to push this work forward, particularly

when dealing with local service providers.

Open-ended engagement and the building of a local mandate was possible within Cynefin

because the PCs were given the scope to build knowledge and relationships over an

extended period of time before they were required to get stuck into the ‘delivery’ of a plan.

In the Cynefin model, this building of a mandate and a locally propelled place-plan was, in

fact, a foundation for and an integral part of the programme delivery. The PCs who were

appointed later in the programme reported some difficulties from having a compressed start

to their work.

Despite these benefits, there were also some reported limits to how far these extended and

how consistently they appear to have been achieved across different PCs. Specifically the

ability of Cynefin, through its more open-ended engagement, to actively engage all members

or sections of the community was felt to be mixed. PCs who had engaged residents in the

Cynefin Monitoring and Learning | A report for Welsh Government

21

management and delivery of a workstream reported that the majority of these were people

already fairly active in their community and/or existing members of a community group.

Likewise, despite the large number of attendees reported at workstream events, and some

success in attracting diverse sections of a local community, there was still a predominance of

“the usual suspects” amongst attendees.

Some PCs that had chosen not to do any visioning events at the start had also reported initial

difficulties and false starts in identifying the priorities of the local community, and

establishing a clear mandate to guide where they directed their efforts, although they

compensated over time by finding other pathways to establishing a mandate. For example,

one PC had directed their initial efforts towards engagement with the local community

around a specific issue suggested by a local service provider. This attracted a muted

response, and it was only through subsequently finding other, more open-ended, means of

establishing local priorities directly from community members that the PC was able to gain

more traction. Notwithstanding the initial concerns some PCs voiced about “over-

consultation”, and even though the PCs who did not do visioning managed to navigate to a

mandate over time, there appear to have been several benefits and no appreciable

downsides to undertaking visioning events or other open-ended approaches early on.

There was an overall sense that the open-ended engagement practised through Cynefin

represented a considerable upgrade on other existing community engagement practices.

Equally, there were still some limits to how far on their own these approaches can

effectively engage all the heterogeneous individuals and subgroups that go to make up a

“local community”.

Building community capacity

One of the intended features of Cynefin, which may have differentiated it from some other

programmes and initiatives, was that the PCs would primarily facilitate local communities to

deliver workstreams rather than doing this delivery themselves. Implicit in this was that PCs

would build the capacities of the communities they were engaging with so they could

undertake key tasks on workstreams, and in the longer term so they were able to lead a

stream of work once Cynefin had ended and go on to initiate and deliver other initiatives