Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr...

Transcript of Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr...

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

1/18

Revue de la rgulation13 (1er semestre / Spring 2013)conomie politique de lAsie (1)

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Alan Cibils et Cecilia Allami

Financialisation vs. DevelopmentFinance: the Case of the Post-CrisisArgentine Banking System

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Avertissement

Le contenu de ce site relve de la lgislation franaise sur la proprit intellectuelle et est la proprit exclusive del'diteur.Les uvres figurant sur ce site peuvent tre consultes et reproduites sur un support papier ou numrique sousrserve qu'elles soient strictement rserves un usage soit personnel, soit scientifique ou pdagogique excluanttoute exploitation commerciale. La reproduction devra obligatoirement mentionner l'diteur, le nom de la revue,l'auteur et la rfrence du document.Toute autre reproduction est interdite sauf accord pralable de l'diteur, en dehors des cas prvus par la lgislationen vigueur en France.

Revues.org est un portail de revues en sciences humaines et sociales dvelopp par le Clo, Centre pour l'ditionlectronique ouverte (CNRS, EHESS, UP, UAPV).

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Rfrence lectroniqueAlan Cibils et Cecilia Allami, Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis ArgentineBanking System , Revue de la rgulation [En ligne], 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013, mis en ligne le 31 mai 2013,consult le 24 juin 2013. URL : http://regulation.revues.org/10136

diteur : Association Recherche & Rgulationhttp://regulation.revues.orghttp://www.revues.org

Document accessible en ligne sur :http://regulation.revues.org/10136Document gnr automatiquement le 24 juin 2013. Tous droits rservs

http://regulation.revues.org/10136http://www.revues.org/http://regulation.revues.org/10136http://www.revues.org/http://regulation.revues.org/ -

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

2/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 2

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Alan Cibils et Cecilia Allami

Financialisation vs. Development Finance:the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine

Banking System

1. Introduction

1 The demise of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s, the crisis of Keynesiandemand-management policies and the growing acceptance and popularity of monetarismin academic and policy circles resulted in a radical shift in macroeconomic and financialpolicies worldwide. The new policies shunned demand management and income redistributionpolicies in favour of broad trade and finance liberalisation, privatisation and deregulation. Theinternational financial institutions, originally created to guarantee the proper functioning ofthe Bretton Woods system, were reconfigured to promote and enforce implementation of the

new liberalisation policies.2 As a result of these global changes, countries in the centre and the periphery underwent radical

policy changes, replacing a system of protections and State intervention in the economy withpolicies aimed at freeing markets from such distortions. The cornerstone of the new policyframework was financial liberalisation, which sought to deregulate national and internationalfinancial markets to rid them of what the monetarist orthodoxy called financially repressivepolicies1. The theoretical and policy shift profoundly transformed the economies of centre andperiphery countries, as well as the international economic arena. Epstein (2005) sums up thechanges as a broad geographical expansion of neoliberal economic policies, a high volume oftrade and financial flows between national economies (globalisation), and financialisation2.

3 As a result, national financial systemsbanking systems in particularwere substantially

transformed. From heavily regulated systems focused on financing investment anddevelopment, banking systems became major players in financial markets. With theprogressive erosion of financial regulation, banks sought higher profits that were not to befound in traditional banking activities, but in various types of financial and investment servicesand consumer credit (dos Santos, 2009).

4 Argentina was not immune to these changes. Starting with the 1976-1983 military dictatorship,the countrys economy began a radical restructuring as a result of the implementation of

a full-scale neoliberal economic programme3. The central piece of the dictatorships policyframework was the 1977 reform of the banking regulatory framework, greatly dreregulating

the sectors activities4. The new policy framework was supposed to usher in an era of greaterefficiency in the allocation of financial and productive resources that would lead to a virtuouscircle of higher growth and investment rates, greater employment and more welfare forall. The virtuous circle never materialised and financial liberalisation policies resulted inthe 1982 debt crisis which, together with the militarys defeat in the Falkland/Malvinas warresulted in the military leaving power in 1983. However, the neoliberal economic policieswere maintained long after the military left power and taken to extremes during the 1990s,including broad trade and financial liberalization and a currency board exchange rate regime,culminating in Argentinas economic depression (1998-2002) and spectacular economic crisis

and sovereign debt default of 2001-20025.5 As a result of the economic crisis, the currency board was abandoned in January of 2002. Under

strong presure from the IMF and against the best judgement of Argentine policy makers, afreely floating exchange rate regime was adopted6. When, as Argentine officials had predicted,a run on the dollar resulted in an ever growing depreciation of the peso, a managed floatexchange rate regime was implemented under strong opposition from the IMF7. The newexchange rate regime, a monetary targets monetary policy, and a widespread government

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

3/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 3

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

subsidy for the unemployed8 provided the fuel to kick-start the economy, which began to growagain in the second quarter of 2002 after four consecutive years of recession.

6 The 2001-2002 crisis revealed the extent of anti-neoliberalism in Argentina. Record levels ofpoverty, indigence and unemployment resulted in mass protests against the IMF and formerpresident Menem, the most recent symbol of neoliberalism in the country. Therefore, whenNstor Kirchner took office in May 2003, he received wide support for his fiery anti-neoliberalrhetoric that lead many to wonder whether his presidency would mean the end of three decades

of free-market policies with their disastrous social and economic consequences. Indeed,Kirchners monetary and exchange rate policies, which he inherited from his predecessor,Eduardo Duhalde, were in direct contradiction to the IMFs prescription. However, manyother policies, especially for the financial sector, were left untouched. As a result, the issue ofwhether Argentina left neoliberalism behind after the crisis is the subject of heated debate.

7 The purpose of this paper is to examine one aspect of this question, namely whether thebehaviour of the post-crisis Argentine financial system differs significantly from its behaviourduring the heyday of neoliberalism and, consequently, whether it is better suited today tofinance development. To do this, we first review two strands of heterodox literature. Thefirst strand deals with the issue of financialisation, a term generally used to describe themarked ascendance of the financial motif in economic activity that has taken place in recent

decades. The second strand of literature deals with the role of banks in the process of economicdevelopment. While there is a long tradition in economics of studying the financing ofdevelopment, this issue has taken on new relevance in the light of recent banking and financialcrises. Following these reviews, we look at Argentine data to see whether there has been aprocess of financialisation in Argentina and to describe salient features of Argentine bankingtoday. The paper concludes with some brief reflections on the implications of our findings forthe financing of development in Argentina.

2. Financialisation vs. Financing Development: a BriefOverview of the Issues

8 While debate on financial liberalisation and its effects has been intense in academic and

policy circles over the last two decades, there is little disagreement on the expansion of bothnational and cross-border financial activity in recent decades. Indeed, according to the Bankof International Settlements (BIS), in 2010 average daily global foreign exchange marketturnover was 4 billion US dollars, up from a 1.5 billion daily average in 1998 and 620 millionin 1989. Baker et al. (1998:10) provide another interesting indicator of this phenomenon. In1950, total funds raised on financial markets were equivalent to 0.5% of world exports. By1980 that percentage had jumped to 5.8% and by1996 funds raised were the equivalent of 20%of world trade.

2. 1. Financialisation

9 In recent years, heterodox economists have focused attention on the increased weight of thefinancial sector and financial transactions in economic activity, a process which has beenbroadly labelled as financialisation9. However, there is no agreed upon single definition forthe term financialisation; rather there are several different, if complementary, definitions.Krippner (2005) has identified four different definitions of financialisation commonly usedin the literature. First, financialisation is sometimes used to describe the dominant place thatshareholder value has taken in non-financial corporate governance10. Second, some use theterm to refer to the growing role of capital markets in financial markets, displacing banksand other financial institutions11. Third, some follow Hilferdings usage to mean the growingfinancial and economic power of financial capitalists or rentiers12. Finally, some authors use theterm financialisation to refer to the explosion of financial trading and innovation in financialmarkets that has taken place in the last decade.

10 Some authors use a fifth definition that combines elements of all of the above definitions.For them, financialisation is the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets,

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

4/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 4

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and internationaleconomies (Epstein 2005:3)13.

11 In general, using these definitions, economists conclude that financial liberalisation andfinancialisation have resulted in the following set of local and global economic transformations(Skott and Ryoo, 2007):

monetary policy oriented almost exclusively to price stability (inflation targeting), a significant increase in the volume of international financial flows, a large expansion of consumer credit for households, a re-orientation of large corporation objectives toward the short-term interests of

shareholders, and a greater influence of the international financial institutions in the global economy.

12 Most research on financialisation is empirical and can broadly be classified in two groupsaccording to whether their focus is microeconomic or macroeconomic. The first group includesstudies that focus on the activities of large industrial corporations, using firm-level data toidentify the ways in which investment and growth are impacted by firms investing in financialassets rather than in productive capacity. Examples of this first grouping are Orhangazis(2007) research on financialisation in the US economy, Demirs (2007) research on a sampleof several peripheral countries, including Argentina, Plihon and Miottis (2001) study of therelationship between financialisation and bank crises and Stockhammers (2004, 2006, 2008)study of the impact of firm-level financialisation on accumulation.

13 A second group of studies focuses on the macroeconomy. Using aggregate sectoral, financialand macroeconomic data, these studies explore mechanisms of financialisation integratingstrategies of a broad number of economic actors. We can broadly classify them according tothe economic school of thought authors subscribe to in regulationist (Boyer 1999, 2000), post-keynesian (Palley 2007) and radical (Krippner 2005, Epstein 2002, 2005, Lapavitsas 2009a,2009b).

14 There are a smaller number of theoretical studies on financialisation, both at themacroeconomic and firm levels. Examples of theoretical models of financialisation are Skottand Ryoo (2007), van Treeck (2007, 2008) and Orhangazi (2007).

15 According to Krippner, the definitions used above and in much of the literature onfinancialisation are centred on economic activity. The problem is that it is often difficult todetermine the existence of a financialisation process based on economic activity and sectoraldata. To have a more complete understanding, it is necessary to expand ones focus to includeextra-sectoral activity and data, in addition to sectoral analysis. Therefore, based on the work ofArrighi (1994), Krippner argues that financialisation is a particular pattern of accumulation inwhich profit-making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through tradeand commodity production (Krippner 2005:181). In other words, it is necessary to study theevolution of sectoral profits and their change over time to be able to fully grasp the processof financialisation.

2. 2. Financial structure and the financing of development

16 Financialisation has not only had a large impact on non-financial corporations. It has alsoresulted in a profound transformation of the banking industry. According to a study of largetransnational banks by dos Santos (2009), bank profits are increasingly generated from loans toindividuals and from services, including investment banking. Thus, bank profits have shiftedfrom the sphere of production to the sphere of circulation. In other words, it is not capitalistprofits that are the main source of financial sector profits, but worker salaries (Lapavitsas,2009d).

17 These transformations, coupled with recurrent financial and banking crises, have revivedthe debate over financial system structure and regulation and their role in the economicdevelopment process. The recent crises in the U.S and Europe have given new life tothese debates and prompted some orthodox and many heterodox economists to call for thenationalisation of banks. Broadly speaking, debate on banking system structure has focusedon two central dichotomies. The first dichotomy consists of debates on whether bank-based

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

5/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 5

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

financial systems are better than market-based financial systems at promoting stability, growthand development. The second dichotomy that has dominated the debate in recent years consistsof intense debates on whether public banking systems are more efficient and stable at financinginvestment and development than privately owned banking systems. We will discuss each

briefly14.18 Debate on bank- vs. market-based systems goes back at least to the work of Gerschenkron

(1962), who compared the development of the British and German financial systems.

According to Gerschenkron, industrialisation in the UK was a slow and gradual processwhere businesses financed investment primarily through retained earnings. In this way,a distant relationship developed between industrial firms and banks, eventually allowingfor the emergence of independent financial markets. Germany, on the other hand, was alate industrialiser where the need for a rapid process of technology incorporation by firmsrequired the assistance of large universal banks to provide financing and managerial support.Eventually, these banks also helped firms coordinate long-term investment needs, acting asinvestment banks as well.

19 While Gerschenkron did not pass judgment on the relative merits of each system, nor why theyendured, the issue has been taken up by many economists and a substantial debate has takenplace on the merits of bank-based vs. market-based systems15. It is generally agreed upon that

bank based systems are better for achieving long-term development goals and for financialstability for several reasons. First, bank-based systems are more likely to achieve positiveresults from expansionary monetary and industrial policies. Second, integration between banksand firms is greater in bank-based systems, generating common objectives which are absentin market-based systems16. Finally, bank-based systems are better at solving informationasymmetry, uncertainty and coordination problems.

20 In the context of peripheral countries, where financial markets are thin and informationand coordination problems abound, the desirability of bank-based systems is even greater.However, with the globalisation of financial systems, the dichotomy between bank-based andmarket-based systems has blurred. Banking systems in the financially liberalised periphery,whether they be bank-based or market-based, have become dominated by the practices of large

international banks from the industrialised countries17

.21 As a result of financial globalisation and cyclical financial crises, and especially as a resultof the world financial and economic crisis which erupted in 2007, debate around a seconddichotomy has intensified. On one side of the dichotomy are economists and policy makerswho argue that private banking and financial markets are necessary and desirable, but moreand better prudential regulation are needed to ensure that irrational exuberance does not gounchecked18. On the other side of the debate is a growing number of heterodox economistsarguing that private banks have failed and that there is a strong case to be made for publicbanks being the backbone of the financial system.

22 Indeed, even Nobel laureates Stiglitz (2009) and Krugman (2009a) have called for thenationalisation of US banks, albeit not permanently. Others have argued, instead, thatpermanent nationalisation is a better solution if stability, investment and development aredesired policy objectives19. Chandrasekhar (2011:274-275) argues that the Glass-Steagalfinancial regulatory framework that prevailed in the U.S. through much of the post WWIIperiod was built on the premise that the role of banks in a capitalist economy is of suchimportance that they had to be regulated in such a fashion where, even though they wereprivately owned and socially important, they would earn less profit than other institutionsin the financial sector and private institutions outside the financial sector. This regulationproduced a deep inner contradiction which, over time, led to substantialand successfulpressures for deregulation.

23 As a result of the internal contradictions of financial regulation and the financialised systemsthat have resulted, Chandrasekhar, Lapavitsas (2009d), Moseley (2009) and other heterodoxeconomists have called for the full nationalisation of banks, not only as a solution to the crisis

but also as a long-run solution to problems of financial instability, financialisation, and rent-seeking activities that do not promote investment and growth. In a similar vein, Krugman

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

6/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 6

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

(2009b) has called for a return to boring banking and Epstein (2010) has called for financewithout financiers.

24 The proposal for a public banking system has sound empirical grounding. Public banking waskey to the successful industrialisation of Asian countries. A successful development strategyrequires investment, and investment requires credit, which Korea and China managed throughpublic banks. In the case of South Korea, nationalisation of the banking system and financial

policies were key to the financing of investment needed for industrialisation20. China has also

achieved high credit/GDP ratios (138% in 2008, six times the Argentine rate), thanks primarilyto its large public banks that finance investment of Chinas large state-owned enterprises21.

25 In the following section we use data from the Argentine economy to examine the post-1990period to see whether Argentina has experienced a process of financialisation. Additionally,we look at financial sector data in order to have a clearer picture of the origin of bank profits.

3. Financialisation in Argentina Since 1990: EmpiricalEvidence

26 The Argentine economy and financial system have undergone a radical restructuring sincethe 1976-1983 military dictatorship introduced full-scale economic liberalisation policies. The1977 financial reform was the starting point of the liberalisation of Argentinas financialsystem, and the Financial Entities Law that liberalised finance is still in place today, with only

minor changes22. During the 1990s, the process was deepened further with the ConvertibilityLaw of 1991 which established the currency board and provided for equal treatment ofdomestic and foreign capital. Financial liberalisation set in motion a process of concentrationand increased foreign ownership in Argentine banking, with public and local private banksincreasingly adopting financial behaviour of the international banks23. While there is littledoubt about the liberalisation of Argentinas financial system, up to what point can we saythat there has been a financialisation process in Argentina?

27 In order to answer this question, we follow Krippners accumulation-based definition offinancialisation. However, as proof of the validity of Krippners critique of activity-baseddefinitions in the case of Argentina, we first look at two sets of data on economic activity:financial sector employment indicators and the relative weight of manufacturing and financialintermediation in GDP.

Table 1. Sectoral and total employment (in thousands and as percentage)

Year Financial Manufacturing Economy Financial/ Financial/

Intermediation Total Manufact. Total

1993 191 2.084 13.234 9% 1,4%

1994 192 1.993 13.036 10% 1,5%

1995 196 1.821 12.654 11% 1,5%

1996 196 1.847 12.881 11% 1,5%

1997 207 1.949 13.632 11% 1,5%

1998 208 1.968 14.189 11% 1,5%1999 200 1.883 14.324 11% 1,4%

2000 211 1.841 14.347 11% 1,5%

2001 216 1.781 14.019 12% 1,5%

2002 196 1.692 13.241 12% 1,5%

2003 191 1.857 13.909 10% 1,4%

2004 199 1.976 14.914 10% 1,3%

2005 214 2.073 15.645 10% 1,4%

2006 228 2.126 16.453 11% 1,4%

2007 253 2.204 17.047 11% 1,5%

Source: Argentine Economy Ministry.

28 Table 1 contains sectoral and total employment data for Argentina during 1993-2007. The1990s were the decade of greatest financial liberalisation in the country, under Menems

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

7/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 7

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

currency board policy and the most extreme privatisation and deregulation policies Argentinahas ever experienced. Therefore, it is the decade where one would have expected to see asignificant increase in financialisation. However, based on sectoral employment data, it isdifficult to reach that conclusion. While employment grew in the manufacturing and financialintermediation sectors, the ratio of financial sector employment to manufacturing and to totalemployment remained virtually constant throughout the entire period. In other words, therewas not a relatively higher growth of employment in the financial sector during this period.

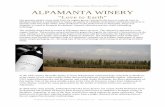

Figure 1. Manufacturing and financial intermediation as a percentage of GDP 1960-2009

Source: Authors calculations based on Ferreres (2005) and Argentine Economy Ministry data.

29 Figure 1 plots the contribution of manufacturing and financial intermediation to GDP for theperiod 1960-2009. The figure clearly shows a growing weight of manufacturing in GDP fromthe early 1960s until the mid 1970s, the end of the import substitution industrialisation period.

From the mid 1970s to the present, there has been a sustained process of de-industrialisation,which is clearly reflected in figure 1. Financial intermediation, on the other hand, is relativelystagnant as a percentage of GDP until the Argentine neoliberal era begins in 1976. From thatpoint on, it has an overall upward trend, with the periods 1976-1982 and 1991-2000 exhibitingthe strongest growth. While it is true that end-to-end financial intermediation doubles itscontribution to GDP, at its highest point in the year 2000 it was only 6.3% of GDP. Based onsectoral data, one would be hard pressed to say that there has been a strong financialisationprocess in Argentina during this period.

30 If we now shift to the accumulation-based approach as suggested by Krippner, we obtain a verydifferent picture of what happened during the period 1990-2010. Krippner suggests that it iskey to observe the variation over time of sectoral profits in an economy in order to get a pictureof how the process of capital accumulation is changing. To do this for the Argentine economy,we took three groups of businesses for the period 1992-2010. The first group consists of non-financial corporations that trade on the Argentine stock exchange (Merval). The second groupconsists of the 500 largest corporations surveyed periodically by the national statistics agency,INDEC (Instituto Nacional de Estadsticas y Censo). The third group is made up of nationaland foreign banks operating in Argentina as reported in the Argentine Central Banks data24.

31 Figure 2 plots average real profits for each of these groups of business for the period1992-201025. Real profit behaviour for the three groups of enterprises does not differsignificantly between the early 1990s and the 2001-2002 crisis. However, during and afterthe crisis the three groups have strongly diverging trajectories. Publicly traded non-financialcorporations experienced negative profits from mid-2001 and through 2002. Still, from the firstquarter of 2003 to the end of the period under study they experienced a remarkable recovery,

with real profits substantially exceeding the levels of the previous decade. Large enterprisessurveyed by INDEC exhibit a similar behaviour, with the exception that they did not

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

8/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 8

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

experience losses during the crisis. Finally, the banking sector exhibits the widest variations.During the latter part of the 1990s, the financial sectors profits did not differ significantlyfrom those of the other two groups of businesses. However, after taking substantial lossesduring 2001-2003, profits recovered remarkably, outstripping the other two groups and at

much higher levels than in the 1990s in real terms26. Given Argentinas highly concentratedeconomy, a trend which began in the 1990s and has continued up to the present 27, this profitbehaviour can be interpreted as a shift in income distribution in favour of the banking sector.

Figure 2. Real average profits of financial and non financial sectors (1993-2010)(in thousands of constant pesos)

Source: Authors calculations based on Argentine Central Bank (BCRA), INDEC, and Economtica data.

32 Based on real profit behaviour, and taking Krippners definition of financialisation, weconclude that there has been a process of financialisation in Argentina in the post-2001-2002crisis period, especially since 2004. At first glance, this may seem odd since the 1990s areknown as the Argentine neoliberal era par excellence. Also, as stated above, there has beena considerable change in official economic policy rhetoric since 2003, which has becomeoutspokenly anti-neoliberal, even if changes in the actual policy framework have not been thatremarkable28.

33 Why, then, has financialisation increased in the post-crisis period? While we do not have adefinitive answer, we believe that the key to understanding post-crisis profit behaviour is thatthe financial liberalisation policies and framework implemented in Argentina since the 1976military dictatorship are still in place at the time of this writing. The profound 2001-2002

crisis and subsequent government bail-out allowed banks to clean out their balance sheets andstart over. Furthermore, as stated above, during the 1990s all segments of Argentinas bankingsectorincluding public banksadopted the behaviour of large international banks, whichhas resulted in hefty profits29. The following examination of the composition of bank profitsconfirms this.

34 Figure 3 shows bank profits from interest, services, and bonds as a percentage of net assetsfor 2000-2010, where we can detect several important trends. First, profits from bonds showan overall upward trend, with peaks during the 2001-2002 crisis (due to the forced conversionof bank deposits to bonds), just prior to the subprime crisis, and in the post-crisis recovery.End-to-end profits from bonds almost tripled during this period. Second, profits from servicesdrop during the crisis and then recover steadily over the entire post-crisis period. Prior to thecrisis, profits from services were lower than profits from interest, however, between 2002 and2008 services generated more profits than interest. Since data are not available prior to the

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

9/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 9

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

crisis, our conclusions are necessarily tentative. It is clear that in the post-crisis period until2008, banks have given priority to generating income from services and fees over traditionalbanking profits from interest rate spreads. The behaviour of Argentine banks is consistentwith the behaviour of large international banks (dos Santos 2009). Although the presence offoreign banks in Argentina decreased in the post-crisis period, domestic private and publicbank behaviour continues to be heavily influenced by large foreign bank behaviour.

Figure 3. Financial system profits from interest and services as a percentage of net assets

Source: Authors calculations based on BCRA data.

35 An examination of traditional bank activity in Argentina is also revealing. Figure 4 shows

total credit and credit to the private and public sectors as a percentage of GDP for the period1993-2009. Total credit grew steadily during the 1990s, but experienced a sustained declinein the whole post-crisis period. Credit to the public sector grew throughout the 1990s and hada very substantial increase during the crisis due to fiscal bail-outs of indebted corporationsand households. During the post-crisis period and until 2007, bank credit to the public sectorexceeded credit to the private sector, indicating that the state was a key source of bank profitsfrom interest. Credit to the private sector also increased during the 1990s, although it wasnever more than 25% of GDP, which is low compared to other peripheral countries (Herr,2008). However, following the crisis, credit to the private sector experienced a sharp declineand never fully recovered to its modest pre-crisis levels.

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

10/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 10

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Figure 4. Financial system credit to private and public sector as a percentage of GDP

Source: Authors calculations based on BCRA and INDEC data.

36 A further look at credit to the private sector also proves revealing. Figure 5 shows bankfinancing by type of economic activity as a percentage of total financing. Bank financingof manufacturing experiences a steady decline during the 1990s, from roughly 35% to 10%of total financing at the time of the crisis. Post-crisis, bank finance to manufacturing firmsrecovers partially, to about 18% of total financing. Bank finance to the primary sector wasrelatively stable during the 1990s, at about 10% of total financing on average. Following thecrisis, financing to the primary sector grew to levels slightly higher than pre-crisis, due mostlyto booming international commodity prices and the expansion of transgenic soy productionwith its associated technological package (large scale mechanised production, herbicides, no-till planting).

37 Financing to individuals experiences a sharp increase in the early 1990s with theimplementation of the Convertibility Plan and then grows steadily throughout the decade.During the crisis, this credit category experiences a sharp drop, as did bank financing tothe private sector in general. However, once the economy began to recover, financing toindividuals increased at a substantially higher rate than credit to other sectors and also at ahigher rate than during the previous decade, reaching 35% of total financing to the privatesector by 2009. Financing to individuals by Argentine banks is fully compatible with thebehaviour of major international banks, as reported by dos Santos (2009).

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

11/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 11

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Figure 5. Financing by economic activity as a percentage of total financing

Source: Authors calculations based on BCRA data.

38 Finally, a further source of bank profits, presented in Figure 3 above, are bonds held as partof their portfolios. While we do not have detailed data of bank portfolio composition, we dohave information on government bonds held by banks. Figure 6 shows total nominal value ofpublic bonds held by banks (left axis) and public bonds held by banks as a percentage of totalbank assets (right axis). Bank holdings of government bonds increased sharply during andafter the 2001-2002 crisis due to forced conversion of bank deposits to bonds, implementedto preserve the banks from the crisis-induced run on deposits. While in nominal terms bankholdings of government bonds continued to increase in the entire post-crisis period, taken as a

percentage of total assets public bond holdings stabilised at approximately 22% after peakingat more than 30% in 2004-2005. From this we can conclude that the state is the source for asubstantial portion of bank profits from bond holdings.

Figure 6. Public bonds held by banks (in millions of pesosleft axisand as a % of totalassetsright axis)

Source: Authors calculations based on BCRA data.

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

12/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 12

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

4. Concluding remarks

39 From the data presented above and using Krippners (2005) definition, we conclude that therehas been a strong process of financialisation in Argentina during the post-crisis period. In otherwords, profits in the banking sector have increased in real terms at a much faster rate than inthe large business sectors.

40 The Argentine 2001-2002 crisis and the policies implemented to deal with it allowed banks

a fresh start in the post-crisis period. With the financial liberalisation policies implementedin the previous decade still intact, banks increasingly conformed to behaviour patterns typicalof large international banks. An examination of bank profits confirms this. Financial serviceshave gained relevance as a source of bank profits, outstripping profits from interest ratespread and financial investments during much of the post-crisis period. Profits from financialinvestments have grown cyclically during the post-crisis era, and bank holdings of governmentbonds are an important source for this type of profit.

41 Regarding profits from traditional banking activities (taking deposits and making loans), datareveal that:

there has been a sustained decline in overall bank credit as a percentage of GDP sincethe crisis;

bank credit to the public sector as a percentage of GDP increased considerably with thecrisis and has since consistently declined; bank credit to the public sector in the post-crisis period was considerably higher than

credit to the private sector until 2007 from which time private sector credit has beenslightly higher than credit to the public sector;

credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP fell sharply with the crisis andeventually stabilised at a level considerably below that of the 1990s average; and

credit to the private sector shifted noticeably away from credit to primary andmanufacturing sectors towards individuals.

42 It is clear from our analysis that Argentinas financialised banking system is not well suitedto provide the support required to accompany a development process. Banks are clearly doing

well, much better than large corporations, and yet they are allocating very limitted financialresources to productive investment and economic development. Instead, following behaviourpatterns of the large international banks, they prioritize short-term profits through consumercredit and other financial activities not directly related to productive investment.

43 Argentina is therefore at a crucial juncture regarding its future. If the country is to truly changeeconomic direction and begin to reverse the effects of 35 years of neoliberal deindustrialisationand reprimarisation, then there is a convincing case to be made that the country wouldgreatly benefit from the nationalisation of its banking system. In addition to the argumentsin favour of nationalisation presented in previous sections, historical evidence in this regardis overwhelming. The examples provided by European and Japanese industrialization andthe more recent example of successful Asian late-industrialisers are sure witnesses to theimportance of State intervention in the banking system to ensure the proper supply of creditfor development. In addition to seriously considering historical examples, it is fundamental tolearn from from their extensive and well documented experience to avoid making the samemistakes.

The authors would like to thank participants at both events and annonymous reviewers for

helpful comments. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Economtica for having

provided temporary, free-of-charge access to data of publicly traded businesses in Latin

America.

Bibliographie

Arestis Philip (2007), Financial liberalisation and the relationship between finance and growth, inArestis Philip and Sawyer Malcolm,A Handbook of Alternative Monetary Economics. Cheltenham, UK:Edward Elgar.

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

13/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 13

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Arestis Philip and Sawyer Malcolm (2004), Re-examining Monetary and Fiscal Policy for the 21st

Century. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Arestis Philip and Sawyer Malcolm (ed.) (2005),Financial liberalisation: Beyond orthodox concerns.Nueva York : Palgrave-McMillan.

Arestis Philip and de Paula Luiz Fernando (ed.) (2008), Financial liberalisation and economicperformance in emerging countries. New York: Palgrave-McMillan.

Arestis Philip and Santonu Basu (2008), Role of finance and credit in economic development, in

Amitava K. Dutt and Jaime Ros (eds.),International Handbook of Development Economics. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.

Arrighi Giovanni (1994), The long twentieth century: Money, power, and the origins of our times.London: Verso.

Azpiazu Daniel, Pablo Manzanelli and Martn Schorr (2011), Concentracin y extranjericacin : LaArgentina en la posconvertibilidad. Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual.

Baker Dean, Gerald Epstein and Robert Pollin (1998), Introduction, in Dean Baker, Robert Pollinand Gerald Epstein (eds.), Globalisation and Progressive Economic Policy. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Basu Santonu (2006), The role of banks in the context of economic development with reference toSouth Korea and India, in Philip Arestis and Malcolm Sawyer (eds.),Handbook of Alternative MonetaryEconomics. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Boyer Robert (1999), Two challenges for the twenty first century: achieving financial discipline andputting the internationalization process in order. CEPAL Review 69, 31-49.

Boyer Robert (2000), Is a finance-led growth regime a viable alternative to Fordism? A preliminaryanalysis.Economy and Society. 29(1), 111-145.

Chandrasekhar C. (2011), Learning from the crisis: Is there a model for global banking?, in Jomo, K.S.(ed.),Reforming the International Financial System for Development. New York: Columbia UniversityPress.

Chesnais Franois (ed.) (1996, 1999),La mundializacin financiera : Gnesis, costos y desafos. BuenosAires: Losada.

Chick Victoria and Dow Sheila (1988), A post-Keynesian perspective on the relation betweenbanking and regional development, in Philip Arestis (ed.),Post-Keynesian Monetary Economics: New

Approaches to Financial Modelling. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.Cibils Alan, Weisbrot Mark and Kar Debayani (2002), Argentina desde la cesacin de pagos : El FMIy la depresin.Realidad Econmica 192, 60-86.

Cibils Alan and Lo Vuolo Rubn (2007), At debts door: What can we learn from Argentinas recentdebt crisis and restructuring?, Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 5(2), 755-795.

Cibils Alan and Allami Cecilia (2010), El sistema financiero argentino desde la reforma de 1977 hastala actualidad : rupturas y continuidades.Realidad Econmica 249, 107-133.

Cibils Alan and Allami Cecilia (2011), El financiamiento bancario a las PYMEs en Argentina(2002-2009).Problemas del Desarrollo 42(165), 61-86.

Cibils Alan, Cecilia Allami and Pilar Piqu (2011), Sistema financiero y desarrollo : Elementos parael debate. Paper presented at the IV Jornadas de Economa Crtica, August 25-27, 2011, Crdoba,

Argentina.Crotty James (2002), The effects of increased market competition and changes in financial markets andthe structure of nonfinancial corporations in the neoliberal era. University of Massachusetts, Amherst:Political Economy Research Institute, Working Paper 44.

Crotty James (2005), The neoliberal paradox: The impact of destructive product market competition andmodern financial markets on non-financial corporation performance in the neoliberal era. In GeraldEpstein (ed.),Financialisation and the World Economy, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Demir Firat (2007), The rise of rentier capitalism and the financialisation of real sectors in developingcountries,Review of Radical Political Economics, 39(3), 351-359.

dos Santos Paulo (2009), On the content of banking in contemporary capitalism. HistoricalMaterialism 17, 180-213.

Dumnil Grard and Lvy Dominique (2001), Costs and benefits of neoliberalism: A class analysis.Review of International Political Economy, 8(4), 578-607.

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

14/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 14

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Epstein Gerald (2002), Financialisation, rentier interests, and Central Bank policy, Universityof Massachusetts. Amherst: Political Economy Research Institute. Paper prepared for conferenceFinancialisation and the World Economy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, December 7-8, 2001.

Epstein Gerald (ed.) (2005),Financialisation and the World Economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Epstein Gerald (2010), Finance without financiers: Prospects for radical change in financialgovernance.Review of Radical Political Economics 42(3), 293-306.

Epstein Gerald and Yeldan Erin (eds.) (2009), Beyond Inflation Targeting: Assessing the Impacts and

Policy Alternatives. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.Ertrk Korkut and zgr Gcker (2009), What is Minsky all about, anyway?Real World EconomicsReview 50, 3-15.

Ferreres Orlando (2005),Dos siglos de economa argentina. Buenos Aires : Fundacin Norte y Sur.

Gerschenkron Alexander (1962), Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Nueva York:Praeger.

Herr Hansjrg (2008), Financial systems in developing countries and economic development, inEckhard Hein, Thorsten Niechoj, Peter Spahin & Achim Truger (eds.), Finance-led Capitalism?Macroeconomic effects of changes in the financial sector, Metropolis-Verlag.

Kotz David (2008), Neoliberalism and financialisation. University of Massachusetts, Amherst:Department of Economics. Paper presented for the conference in honor of Jane DArista, Political

Economy Research Institute, May 2-3.Kregel Jan (1996), Origine e sviluppi dei mercati finanziari. Arezzo : Banca popolare dell Etruria e delLazio/studi e ricerche.

Kregel Jan (1998), The Past and Future of Banks. Ente Einaudi : Roma.

Krippner Greta (2005), The financialisation of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2),173-208.

Krugman Paul (2009a), Banking on the brink. The New York Times, February 23.

Krugman Paul (2009b), Making banking boring. The New York Times, April 10.

Lapavitsas Costas (2009a), Financialisation, or the search for profits in the sphere of circulation, Schoolof Oriental and African Studies, Discussion Paper No. 10.

Lapavitsas Costas (2009b), Financialisation embroils developing countries, School of Oriental andAfrican Studies, Discussion Paper No. 14.

Lapavitsas Costas (2009c),El capitalismo financiarizado : Expansin y crisis. Madrid: Maia Ediciones.

Lapavitsas Costas (2009d), Systemic failure of private banking: A case for public banks. London, UK:School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Economics, Research on Money and FinanceWorking Paper 13.

McKinnon Ronald (1973),Money and Capital in Economic Development. Washington, DC : BrookingsInstitute.

Ministerio de Economa (2004), Argentina, el FMI y la crisis de la deuda.Anlisis 1(2).

Moseley Fred (2009), Time for permanent nationalisation,Dollars and Sense, March 3.

Orhangazi zgr (2007), Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate

sector: A theoretical and empirical invstigation of the US economy 19732003. University ofMassachusetts, Amherst:Political Economy Research Institute: Working Paper 149.

Palley Thomas (2007), Financialisation: What it is and why it matters. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY:The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Working Paper No. 525.

Patrick, Hugh (1966), Financial Development and Economic Growth in Developing Countries,Economic Development and Cultural Change, 14(2), 174-189.

Plihon Dominique, Miotti Luis (2001), Libralisation financire, spculation et crises bancaires .Larevue du CEPN85.

Pollin Robert (1995), Financial structures and egalitarian economic policy, University ofMassachusetts, Amherst:Political Economy Research Institute, Working Paper 182.

Shaw Edward (1973),Financial Deepening in Economic Development. New York: Oxford UniversityPress.

Skott Peter and Ryoo Soon (2007), Macroeconomic implications of financialisation, University ofMassachusetts, Amherst:Department of Economics Working Paper 2007-08.

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

15/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 15

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Stiglitz Joseph (2009), A bank bailout that works. The Nation, March 4.

Stockhammer Engelbert (2004), Financialisation and the slowdown of accumulation. CambridgeJournal of Economics, 28(5), 719-741.

Stockhammer Engelbert (2006), Shareholder value-orientation and the investment-profit puzzle.Journal of post Keynesian Economics, 28(2), 193-215.

Stockhammer Englebert (2008), Some stylized facts on the finance-dominate accumulation regime.Competition & Change 12(2), 184-202.

Tonveronachi Mario (2006), The role of foreign banks in emerging countries: The case of Argentina1993-2006.Investigacin econmica, LXV(255), 15-60.

Van Treek Till (2007), A synthetic stock-flow consistent model of financialisation. Dsseldorf:Institutfr Macrokomie (IMK), Working Paper 6/2007.

Van Treek Till (2008), The political economy debate on financialisationa macroeconomicperspective. Dsseldorf:Institut fr Macrokomie (IMK), Working Paper 1/2008.

Wray L. Randall (2010a), What Should Banks Do? A Minskyan Analysis. Annandale-On-Hudson,NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Public Policy Brief 115/2010

Wray L. Randall (2010b), What do banks do? What should banks do? Annandale-On-Hudson, NY:The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Working Paper 612.

Zysman John (1983), Governments, Markets and Growth: Financial Systems and the Politics ofIndustrial Change. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Notes

1 The neoliberal orthodoxys justification for financial liberalisation is based on two hypotheses oferroneous theoretical grounding and very little substantiating empirical evidence. The first is the financialliberalisation hypothesis, based on the writings of Patrick (1966), McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973).According to this hypothesis, low growth rates in the developing world were due to low domesticsavings rates, which were due to financial repression, i.e. State regulation of financial markets, interestrate caps, and credit allocation policies. Therefore, once markets were freed from such fetters. Thehypothesis is based on the questionable assumption that credit depends on saving and that saving financesinvestment. See Arestis (2007), Arestis and Sawyer (2005), Arestis and de Paula (2008), Arestis and Basu

(2008), Chesnais (1999) and Chick and Dow (1998) for more detailed critiques. The second hypothesisis the efficient financial market hypothesis according to which capital market prices are supposed toalways fully reflect available information. The well documented problems of financial markets, such asherd behaviour, self fulfilling prophecies and financial speculation bubbles among others, should havedictated the death sentence to this hypothesis. However, it is still alive and well in orthodox literature.

2 As we shall see in the following section, there are different definitions of the term financialisationdepending on whether they focus on economic activity or on the accumulation process, although theygenerally complement each other.

3 For a detailed description of the transformations that took place in the financial system, see Cibils andAllami (2010).

4 Cibils and Allami (2010) provide a detailed account of this regulatory change and its effects.

5 See Cibils et al. (2002) for an account of the process leading up to the crisis.

6 See Ministerio de Economa (2004) for a revealing insider account of the IMFs considerable mistakesin handling Argentinas crisis.

7 In April 2002, at the lowest point of the Argentine crisis, then-president Duhalde appointed RobertoLavagna as economy minister. Despite strong IMF pressure to the contrary, Lavagna implemented aquantitative targets monetary policy and a managed or dirty float exchange rate regime. The IMFsprescription is a freely floating exchange rate regime and an inflation targeting monetary policy. For acritique of these policies see Arestis and Sawyer (2004) and Epstein and Yeldan (2009).

8 The subsidy, known as the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados, had as many as two millionbeneficiaries at its point of highest enrollment.

9 See, for example, Chesnais (1999), Crotty (2002, 2005), Demir (2007), Epstein (2002, 2005), Kotz(2008), Krippner (2005), Lapavitsas (2009a, 2009b, 2009c), Orhangazi (2007), Palley (2007), Skott andRyoo (2007) and Stockhammer (2004), among others.

10 E.g., Crotty (2002, 2005).

11 E.g., Ertrk y zgr (2009) y Pollin (1995) among others.

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

16/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 16

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

12 See, for example, Epstein (2002), Demir (2007).

13 See also Epstein (2002), Palley (2007) y Kotz (2008).

14 For a more extensive discussion of these issues, see Cibils et al. (2011).

15 See Pollin (1995), Kregel (1996, 1998) and Zysman (1983), among many others.

16 Minsky wrote extensively about this aspect of bank-based systems. For Minsky, in bank-basedsystems banks act as intermediaries between firms and financial markets, but hold on to firm equitiesas part of bank assets. In this case, solid underwriting is key, as the banks success is tied to the firms

success. This does not occur in market-based systems, where banks do not hold on to firm equities.In these systems, where firm equities are quickly sold on secondary markets, underwriting is not asimportant since bank success is not linked to firm success [see Wray (2010a, 2010b) for an in-depthdiscussion of Minskys views] .

17 See Dos Santos (2009) for the changes that have taken place in large international bank operations.Tonveronachi (2006) analyzes the impact of the penetration of large international banks in Argentinaon domestic private and public banks. He concludes that local banks, both private and public, haveessentially adopted the international bank modus operandi. Allami and Cibils (2011) arrive at the sameconclusion from a study of bank finance of small and medium businesses in the post-crisis period.

18 Readers will recall then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of the United States Alan Greenspansuse of the term during the dot com bubble in 1996.

19 Moseley (2009), Lapavitsas (2009d) and Chandrasekhar (2011), among others.

20 Basu (2006) and Arestis and Basu (2008).

21 Herr (2008).

22 For a detailed account of the financial reform and its effects, see Cibils and Allami (2010).

23 Tonveronachi (2006).

24 For publicly traded non-financial corporations and for the large businesses surveyed by INDEC, weused total profits without discriminating whether they were the product of financial investments. For thebanking system profits, we took annual ROA (return on assets) multiplied by the yearly average assetstock, as published by the Argentine Central Bank. Since each group has different numbers of enterprises,which also vary over time, we divided total profits by the number of enterprises in each category eachyear. These calculations enabled us to compare profits across groups. Due to the unreliability of INDECprice data, all profits were deflated by a composite price index built from data of seven of Argentinaslargest provinces. Finally, the number of financial institutions in the sample remained relatively stablethrough out the period, so the spike in financial sector profits at the end of the period is not due to a

decrease in the number of financial institutions.25 Krippner suggests looking not only at sectoral profits but also at their composition, thus showingto what extent profits in each sector are being generated through financial investments. Due to lack ofavailability of detailed data, we only studied sectoral profits, not their breakdown. Had we been able todetermine the percentage of big business profits generated through financial investments, financial profitgrowth would have been even greater.

26 It has been suggested that banking sector profits may have been so high after 2004 in order to fulfilBasel II balance-sheet requirements following the substantial losses in the immediate post-crisis period.However, the strong growth of profits in the last two years of the period under study would indicate thatthere is, indeed, a change in behaviour of banking profits.

27 See Azpiazu et al. (2011) for Argentine economy concentration trends, especially in the post-crisis era.

28 The greatest break with the convertibility regime of the 1990s was implemented in April 2002 by then-president Eduardo Duhalde and his economy minister Roberto Lavagna. At that time a managed floatexchange rate regime was implemented, together with a monetary targets monetary policy. In 2005, aChilean-style capital control policy was implemented to try to avoid short-term capital flow disturbances.However, the financial system regulatory framework is provided by the Military Dictatorships 1977Financial Entities Law, which liberalised finance in Argentina.

29 Tonveronachi (2006) finds that private and public domestic banks adopted behaviour of internationalbanks after liberalisation. Dos Santos (2009) describes the behaviour of large international banks. Manyof these behaviours are observed also in Argentina.

Pour citer cet article

Rfrence lectronique

-

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

17/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 17

Revue de la rgulation, 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013

Alan Cibils et Cecilia Allami, Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-CrisisArgentine Banking System ,Revue de la rgulation [En ligne], 13 | 1er semestre / Spring 2013, misen ligne le 31 mai 2013, consult le 24 juin 2013. URL : http://regulation.revues.org/10136

propos des auteurs

Alan Cibils

Chair, Political Economy Department, Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, Argentina,[email protected] Allami

Professor, Political Economy Department, Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, Argentina,[email protected]

Droits dauteur

Tous droits rservs

Rsums

The end of the Bretton Woods era and the emergence of neoliberal economics resulted inprofound transformations in domestic economies and international economic relations. Thekeystone of these transformations was the liberalisation of domestic and international financialmarkets. Faulty theoretical foundations and the resulting catastrophic policy failures prompteda vast literature by critical economists on the international financial architecture and domesticfinancial structures best suited for economic development. In recent decades, debate has alsocentred on what has been labelled financialisation, i.e. the increasingly central role playedby financial markets and transactions in economic activity. In this paper we try to ascertainwhether Argentina experienced a process of financialisation between 1990 and 2009 and whatimpact, if any, it has had on Argentine banking. We conclude that there has been a strongprocess of financialisation in Argentina in the post 2001-2002 crisis period. We also explorein a preliminary fashion potential reasons behind Argentine post-crisis financialisation. Thepaper concludes by suggesting that it is time to consider alternative banking arrangements ifdevelopment finance is to become a policy priority.

Financiarisation vs. financement du developpement : le cas dusystme bancaire argentin dans laprs-crise

La fin de lre Bretton Woods et lmergence dune conomie nolibrale ont eu pourconsquence de profondes transformations des conomies nationales et des relationsconomiques internationales. La cl de vote de ces transformations a t la libralisation desmarchs financiers nationaux et internationaux. Des rfrences thoriques errones et lchec

des politiques catastrophiques qui en dcoulaient ont donn lieu une littrature importantepar des conomistes critiques sur larchitecture financire internationale et les structuresfinancires nationales les mieux adaptes au dveloppement conomique. Depuis quelquesdcennies, le dbat est galement centr sur ce qui a t tiquet financiarisation , cest--dire le rle de plus en plus prpondrant jou par les marchs et les transactions financiresdans lactivit conomique. Nous allons tenter, dans cet article, de dterminer si lArgentinea connu un processus de financiarisation entre 1990 et 2009 et limpact, le cas chant, dece processus sur le systme bancaire argentin. Nos conclusions tablissent quil y a eu unintense processus de financiarisation en Argentine dans la priode daprs crise 2001-2002.Nous recherchons galement en prliminaire les raisons possibles de la financiarisationde lArgentine dans laprs-crise. Larticle conclut en soulignant quil serait temps, si le

financement du dveloppement devait devenir une politique prioritaire, denvisager despratiques bancaires alternatives.

mailto:[email protected]:[email protected]:[email protected]:[email protected] -

7/29/2019 Cibils Allami.financialisation vs Development Finance the Post Crisis Argentine Banking System.rr n13 2013

18/18

Financialisation vs. Development Finance: the Case of the Post-Crisis Argentine Banking S (...) 18

Financiarizacin versus financiamiento del desarrollo : el caso delsistema bancario argentino luego de la crisis

El fin de la era de Bretton Woods y de la emergencia de una economa neoliberal tuvo comoconsecuencia profundas transformaciones de las economas nacionales u de las relacioneseconmicas internacionales. La llave maestra de esas transformaciones fue la liberalizacinde los mercados financieros nacionales e internacionales. Las referencias tericas errneas yel fracaso de las polticas catastrficas que generaron dieron lugar a una literatura importantepor parte de economistas crticos sobre la arquitectura financiera internacional ms adaptadasal desarrollo econmico. Desde hace varias dcadas, el debate se centr sobre lo que se hadenominado financiarizacion, es decir el papel cada vez mas preponderante jugado porlos mercados y las transacciones financieras en la actividad econmica. Vamos a intentaren este artculo determinar si Argentina ha conocido un proceso de financiariacion entre1990 y 2009 y, en ese caso, el impacto sobre el sistema bancario argentino. Nuestrasconclusiones establecen que hubo un intenso proceso de financiarizacin en Argentina en elperiodo posterior a la crisis de 2001-2002. Nosotros tambin buscaremos primeramente lasrazones posibles de la financiarizacin de Argentina luego de esa crisis. El artculo concluyedestacando que ya habra llegado el momento de proponer prcticas bancarias alternativas enel caso de que el financiamiento del desarrollo llegara a ser una poltica prioritaria.

Entres dindex

Mots-cls :financiarisation, systme financier, libralisation financire, ArgentineKeywords :financialisation, financial system, financial liberalisation, ArgentinaPalabras claves : financiarizacin, sistema financiero, liberalizacin financiera,ArgentinaCodes JEL :E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy, E51 - Money Supply;Credit; Money Multipliers, N26 - Latin America; Caribbean

Notes de lauteur

This version of the paper was prepared for the Second IIPPE Conference, Istanbul, Turkey,May 2011. An earlier version was presented at the II Jornadas de Economa Poltica, November9-11, 2009, Los Polvorines, Buenos Aires.