Between Catwalk and Studio

-

Upload

deinera642 -

Category

Documents

-

view

102 -

download

1

Transcript of Between Catwalk and Studio

Fashion Theory, Volume 13, Issue 1. pp. 7-28DOI; 10,2752/175174109X381337Reprints available directly from the Publishers,Photocopying permitted by licence only.© 2009 Berg,

Antje Krause-Wahl

Between Studioand Catwalk—Artists in FashionMagazines

Antje Krause-Wahl holds a PhDin an history and is currentlyteaching at the Akademie of FineArts, Mainz, She is co-editor ofErblatterie Identitäten. Mode-Kunst—Zeitschrift ¡Jonas. 2006),a book that accompanies anexhibition of the same title. A recentarticle on architecture in Harper'sBazaar is published in AnnetteGeiger {ed.) Der schöne Körper(Böhlau, 2008),krausewa@uni-mainz,de

Abstract

Looking at photographs of artists in their studios during the 1940sand 1950s, fashion spreads of artists as models in the 1960s and theearly 1970s and in current fashion spreads, this article traces the shift-ing modes of representation from studio to catwalk. Paying attentionto magazines as "instruction manuals," the term "model" is used tounderstand the staging of the artist. In looking closely at how images ofartists are integrated in the magazines' layout, it is argued that fashionmagazines assign a creative potential to the artist, which first is con-nected to their work in the studio but which also extends to include the

Antje Krause-Wstfil

self-creation and reflection of the artists' identity. This twofold creativ-ity is variously staged, making the artists attractive to the readers andfinally setting out a role model for them "on the catwalk."

KEYWORDS; fashion magazine, fashion photography, model, Vogue,Harper's Bazaar, art and fashion

In Spring 2005 the Berlin magazine Monopo/claimed Hanne Darboven,Jonathan Meese, Tracey Emin, Rachel Feinstein, Jean-Michel Bas-quiat, and Joseph Beuys to be fashion icons. Drawings of their image-constituting pieces of clothing were accompanied by a text stating thatequal to professional models and actors, artists are now active in thefashion business—their public appearances are meticulously docu-mented and their best outfits often find their way into Vogue's column"Talking Fashion" (Monopol 2005: 84-9).

Leafing through current fashion magazines, one v̂ iill find that thisarticle mentions only one aspect of current associations between artistsand fashion. There are many more: the spectrum reaches from tellingwhich brands are worn in the studio to fashion spreads showing modelsappropriating artist's habitus m fashion and pose.'

The presence of artists in fashion magazines however is not new;since the 1930s Vogue and Harper's Bazaar have frequently reportedfrom the artist's studio. But this large extent of the contemporary pres-ence of artists in magazines is my reason to outline the history anddevelopment of this phenomenon taking into consideration not only theabove magazines but also L'Uomo Vogue and Purfile Fashion to discusschanges in relation to a different readership as well. My focus will beon photographs of artists in their studio from the 1940s and 1950s, thepicturing of artists as models in the 1960s and early 1970s and in cur-rent fashion spreads.^ I will pay special attention to the characteristics ofthe magazines themselves as products, which are designed as "desirableobiects" (Breward 2003: 123) by photographers and art directors. Forthis reason, not only single photographs will be discussed, but also thelayout of the fashion spreads and their situating within the magazines.

Over the last few years the critical literature on the fashion magazinehas grown. Scholars bring into focus the image-text relation (Jobling 1999)or, like a recent issue of Fashion Theory (Fashion Theory, Vol. 10 (1/2),2006) on Vogue, their politics of taste making and shaping nationalidentities. But still the presented and changing concepts of genderedidentities are of importance. For instance Jennifer Craik, following RosBallaster on the world of the woman's magazine (Ballaster 1991), ex-amines the function of fashion magazines as "instructional 'manuals'"for the training of "femininity" (Craik 1994). Through role models andinstructions "techniques of femininity" are conveyed—including ev-erything from body care over conduct, patterns of behavior to moralattitudes in all areas of everyday life. In order to describe the subtle

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines

processes of identification vwith the images of femininiry made fetish,feminist critics put psychoanalytical theories into play and the gaze ischaracterized as desiring.' Looking at magazines from a historical per-spective, Leslie Rabine observed in her study on Anglo-American fash-ion magazines a significant shift. She states, that from 1960 to 1980, theimplied (female) reader changed from one who "uncritically imitates anestablished social role" into one who "produces a self through a pro-liferation of theatrical roles created through a judicious use of costumeand masquerade" {Rabine 1994: 64). On top of that, during the processof the programmatic shift from feminist theory to gender studies, theman, too, entered into view as consumer and addressee of fashion andlifestyle magazines (Bostnar 2002; Crewe 2003).

Paying attention to the assumed processes of identification via thegaze, but also taking into account shifting ideas of the readers, the term"model" is central to my considerations towards an understanding ofthe staging of the artist in these ever-changing constellations.'' Severaldiscourses meet in this term: "model" is not only a synonym for man-nequin, it also means "a model for artistic studies" and is thereforeequally connected to the artist's studio. Thus, the magazines present toits readers, on the one hand, models/mannequins with whom they can/should identify. At the same time, the magazine includes presentationsof the "artist in the studio," that is, the space in which the idea of thecreative male artist is activated through the relationship hetween artistand model. What happens to the artist when he is presented next to themodel/mannequin in the fashion magazines? And, moreover, what hap-pens when the artist leaves the studio and becomes a model him-/herselfand in this process traditional positions, the creative male artist and thefeminine model, who is looked at, get mixed up?

But I want to take into consideration another aspect of the term"model" as well. In connection with the current fashion magazine's in-terest in artists, a more general question appears: "model" means alsoan original that is basis for a "reproduction." I like to state, that bymeans of fashion magazines, the shifting ideas of the artist can be char-acterized: this is because the fashion magazine is exactly the place inwhich artists, presented as models, become models, in the sense of "rolemodels," for their readers.

In the Studio

In Vogue and Harper's Bazaar references to art have a long tradition.Vogue's art director Alexander Liberman (1943-61) traveled since 1947to France every year in order to photograph European avant-garde art-ists in their studios. Vogue regularly showed a selection of these photo-graphs accompanied by short texts, which became well known in 1960,when the Museum of Modern Art dedicated Liberman an extensive

10 Antje Krause-Wahl

exhibition and he published the book The Artist in His Studio (Liber-man 1960). But also Harper's Bazaar with his art director AlexeyBrodovitch (1934-58) featured artists of the European and later theAmerican avant-garde.^

The roie of the artists' presentations in the aforementioned maga-zines has been characterized by Mary Bergstein: "Interspersed amongfine-point of etiquette and fashion, these pictures brought the legendof the modernist artist to women within the realm of fashion-magazinefantasy. In this context, it seemed 'natural' for North American womento study a photograph of a model wearing a Dior dress within secondsof having contemplated a photo essay of Picasso in his studio" (Berg-stein 1995; 45). Caroline A. Jones argues looking at Alexander Liber-man: "Life of these texts and images has been rich, spread over manysectors of American society and enduring over decades. We can locatehere a primary source for the post-war Américanisation of the isolatedRomantic artists" (Jones 1996: 28).

These observations leave certain questions unanswered. Why wereimages of artists, including the mentioned myth creation, taken on asinteresting in the context of Fashion magazines, where the readers con-sume fashion and images of femininity in looking at and identifyingthemselves with the female models? A close look on the presentation ofthe model in relation to art might help us.

Browsing through magazines one can find different visual strate-gies bringing models and artworks together. It is very common for theabove-mentioned journals to introduce a collection or report from anexhibition. Some of these articles are obviously connected to pictures ofmodels. The British edition of Vogue in January 1950 shows paintings ofwomen by "old masters" (Watteau, Terborch, Chardin, Botticelli, van derWeyden). The article with the headline "When the mind loses its feelingfor elegance it grows corrupt" (British Vogue 1950: 36-^5) praises thepainter's sense for elegance in drawing attention to the texture and colorof fabrics and the "characters of the model's souls," that are "drawn inline of flesh and bone." Under the same headline the reader finds pho-tographs of society ladies (Lady Pamela Berry, Miss Clarisse Churchill,Lady Birley with daughter) by Cecil Beaton. These women wear designsby Schiaparelli or Paquin, their poses take up those represented in thepaintings, thus connecting printed artwork and photograph.

We every so often see photographs of models together with art ingalleries or museums. In the January 1945 issue of American Vogue,models, dressed in the new "uncluttered look," pose next to a sculp-ture of Brancusi, in front of a Mondrian and an Interior Design byTerence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings. Especially during the last yearsof World War II Vogue reported regularly from the front. This issueshows Paris designs during 1940 introduced as "fashionable resistance"against the German occupation and images of a visit on an aircraft car-rier. Due to the involvement of the USA in World War II, the article

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 1 1

emphasizes the "uncluttered look" as a "sort oí minor comfort." Butat the same time the reduced shape of clothes and the minimal accom-panying accessories are nevertheless compared to artworks and an inte-rior design that still signify luxury and sophistication (American Vogue1945: 42-7). John Rawling, like Beaton, tries to translate the "serenedimensions" of the Brancusi in the photograph as well. He places thesculpture in the center, the model is only seen half-cut, so emphasizingthe simple, geometric forms of the dress—you do not need the other halfto imagine the whole.

In hoth strategies the model is correlated with the artworks: eitherthrough the sequence of paintings and photographs or within the imageitself (when the model poses with an artwork). Such the photographertakes over the role of an artist: he "pictures" the modei with his camerain a way that makes his photographic staging correspond with artworks,or, like Beaton, self-consciously compares his photographs with exist-ing paintings. At the same time fashion is revaluated hy art; the fashionphotograph itself is raised to the level of an artwork.

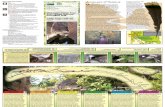

But the January 1945 issue of American Vogue also features tra-ditional studio portraits: images of Matisse and Bonnard are tellinglyplaced a few pages after the already described fashion spread (AmericanVogue 1945: 50-1, photographer André Ostier). Both hold brushes inhand, sitting or standing in front of an easel, Matisse Is shown with amodel (Figure 1). The accompanying text describes their isolation inFrance during World War II and together with the images of AndréOstier the myth of the isolated romantic artist is put into play. But flip-ping through the magazine, it is striking that between the "unciutter"images, that are accompanied by the appeal "You might try to makea new design of yourself" (American Vogue 1945: 43) and the photo-graph of the artists, two pages encourage the female readers to seize thecrayon themselves. To practice, they should blacken out the superfluousaccessories of a furnished room and of an outfit to make it fashionable(Figure 2). In the flow of the pages, the artists are placed as inspiringsource for female activities like decorating and dressing up.

This is also the case in another studio photograph of Matisse.'' InFebruary 1949 American Vogue published an article ahout his interiordesign for the Dominican chapel "Sainte Marie du Rosaire," showing aone page photograph hy Clifford Coffin.̂ The text talks about the ar-tistic project, the photograph depicts the bedridden artist in his studioin Nice. Meticulously dressed in shirt, tie, and pullover, he is workingon a paper cut. Its flower pattern permeates the entire composition: infront of the hed's frame, whose ornaments apparently have inspiredthe paper cut, lie finished paper cuts. The mirror in the backgroundshows them on a door frame, even the hair of the drawn portraits ofwomen placed as a frieze on the wall, pick up the same wavy lines.A photograph on the next page is taken from the perspective of theartist, who can view the living room/studio from this bed. In a magazine

12 Antje Krause-Wahi

IIKMll M\Tt\SK

Figure 1Matisse in American Vogue.January 1 1945: 50, photograph byAndré Ostier, Courtesy of Vogue,Conde Nast Publication Inc,

concerned with the art of tailoring, Matisse, working with his scissors,becomes a fashion and an interior designer of the homely environmentat the same time. Here making fashion and making art are closelylinked, and he has taken over a role that lies within the area of women'sactivities."

These few examples show that there are different methods and pos-sible reasons for placing images of art and artists next to the fashionpages of the magazines. Looking over the visualized relation betweenmodel and artwork first, it will become clear that the designers of fash-ion magazines, by including art and artists, appropriate their creativerole. In this way one could interpret the artist presentations as substi-tutes for photographer or art director.' Moreover, with the studio imagesnot only the image of the isolated, romantic artist is promoted; artistsare engaged in a creative act that is thought of as male, but in the caseof Matisse is closely linked to the female reader's assumed activities.*"In May 1954 Louise Dahl-Wolfe tellingly takes up the work of Ma-tisse in a fashion spread in Harper's Bazaar. In the photographs themodels apparently create holding scissors in their hands the paper cutsthemselves—imitations of "La Perruche et la Sirène" (1952)—that formthe background of the fashion presentation (Harper's Bazaar 1954:120-5).

On the Catwalk

Photographs of artists within the fashion magazine necessarily turnedthe attention to the clothes worn in the studio, but their status as

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 13

Figure 2"Unclutter" in American Vogue. January 1 1945: 48-9, illiistrations by Priscilia Peck.Courtesy of Vogue, Conde NasI Publication Inc.

fashionable outfits did not attract interest at first." It is in the October1963 issue of Harper's Bazaar that Marisol Escobar appeared as a modelwithin the regular "Fashion Independent" series, in which famous andsuccessful women show fashion (Harper's Bazaar 196.3b: 198-201).'-The interest in Escobar was triggered by the Museum of Modern Art'sexhibition Thirteen Americans, in which her work occupied a wholeroom." On the first double page, three photographs by Duane Michalsshow Escobar in the exhibition next to some of her wooden sculptures.Her trousers, boots, and the casual sweater are defined in a short textas her working clothes, accompanied by the information where theycan he purchased (Figure 3). The following pages show Escobar in adiscotheque, wearing a "stark white crepe evening dress" and in herapartment, where she poses in a "banker's grey wool flannel Empirelounging dress." Further works of art are shown, but these merelydecorate a discotheque or are described as results of a creative leisureactivity: "at home after working hours—she displays one of her dollsshe makes just for fun,"

It is striking that Escobar's poses on the first pages match her ob-jects: Her half profile mirrors that of the sculptured horse and she posesmotionless between her sculptures in the museum space. Even the darkplane, which is painted on one of Escobar's sculptures, is taken up inthe harsh light and shadow contrast Duane Michals uses in his photo-graphs. Through these correspondences between the artist and her art-work, Marisol Escobar becomes a sculpture; the creative subject turnsinto an object of the photographic gaze.

Further correlations are created suhtly in the arrangements of thephotographs: While on the one in the upper left-hand corner the artistseeks eye contact with the spectator, the other photographs correspond

14 Antje Krause-Wahl

Figure 3Marisol Escobar in Harper's Bazaar, October 1963: 198-9, photographs by Duane Michals, Courtesy of Duane Michals.

with each other in a way that leads the reader's gaze, via the gaze ofMarisol Escobar, beyond the edge of the page. Leafing backwards onefinds actors and Broadway script writers ("Good Theatre: The Man toWatch, and the Clothes to Wear"), also photographed by Duane Mi-chals {Harper's Bazaar 1963a: 176-9; Figure 4). They pose with one ormore models on a stage harshly lit by spotlights. The male protagonists,unlike Marisol, look directly into the camera, while, as in the case ofMarisol, the profiles and hody contours of the models are emphasized.Their gazes are upon the male protagonists or they support those of themen aimed beyond the image frame.

Harper's Bazaar presents—and here I follow the analysis of CécileWhiting—Marisol Escohar not only as an artist who is a fashionablewoman, but much more as a "Eashion Independent," who (incidentally)happens to he an artist (Whiting 1997: 210). In Système de la modeRoland Barthes, examining the Erench magazines Elle and Jardin des

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines Ifl

Figure 4Harper's Bazaar, October 1963:176-7, photograph by DuaneMichals, Courtesy of DuaneMichals,

Modes from June 1958 to June 1959, claimed that presented femaleoccupations indeed creates a point of reference, which gives the modelan identity, that nevertheless soon evaporates. The secretary, the booksaleswoman or the student are less characterized through their activities,these employments give rather access to a position in society (Barthes1990: 259). Even if Harper's Bazaar is aimed at a different readership(you will hardly find models with those jobs in it), his observation istransferable: it seems that Marisol Escobar's "job" as an artist gives ac-cess to a position in society that goes along with special activities suchas a dressed up visitor of a museum or a discotheque. The process ofindividualization, i.e. the freedom from predetermined "traditional pat-terns of life," the multiplication of ways of living and possible biogra-phies with new spaces for action, had still not found their way into thefashion magazines (see Rabine 1994).'"'

To offer the possibility of being identified with, the woman artist mustnot only wear different pieces of clothing, she must simultaneously slipinto more everyday female roles appropriate for a society lady, and herartworks evidently serve merely to support this {self)staging. But in myopinion not only photographs but likewise the layout emphasizes her roleas a model." Elipping through the pages one does not notice that, unlikein the above described examples of studio portraits, there is now an artiston display.

But nevertheless, the presentation of Escobar is somehow ambiva-lent. On the one hand, her profession as an artist is not centra!—she isnot shown producing her work, an activity that is reserved for the male

16 Antje Krause-Wahl

artist and would be in conflict with the role she is given. But anyway,an individualization can be glimpsed in Marisol: even though she isreferred to by her first name, and in this way grouped with the mod-els, she is not a usual one, because she is presented as a successful andindependent working woman. Visually, the conflict between having anactive role and looking good and fashionable is staged, but at the sametime it seems that the creative woman as "model" for an attractive self-fashioning is also of possible interest for the readers."^

Compared to Harper's Bazaar and Vogue, L'Uomo Vogue., which wasreleased in 1969 for a male audience, presented a large numher of fash-ionahly dressed men who work in creative occupations: actors, musicians,artists, '̂' and the fashion designers themselves. With this strong focus onthe site of production the magazine introduced to their readers the ideathat to be fashionable and to be male do not exclude each other. Fashionspreads with Karl Lagerfeld, the "creatori della moda," who is photo-graphed from below with models arranged around his feet, show, thatnevertheless gender hierarchies are still at work (L'Uomo Vogue 1969).

Andy Warhol, who was himself active in the fashion business, work-ing for magazines and launching in 1969 his own magazine Inter/View,is frequently present as a model in L'Uomo Vogue."* The 1974 Springissue starts with a reprint of a group photograph of the Factory mem-bers, already shown in L'Uomo Vogue in 1972 {L'Uomo Vogue 1972:162-3, photographer Oliviero Toscani). When in 1972 Oliviero Toscanidepicts "his heterogeneous group of friends," dressed in individual lei-sure style, now his employees are dressed in suits available at BrooksBrothers—an accompanying text clearly defines their jobs (Alheroni1974: 122-7).^' The following two pages show Warhol wearing fittingattires for all occasions, from suit to housecoat, with brands and pricesmentioned next to the images (Figure 5). With his outfit he promotesa new "conservative" style—the return of the suit, that is establishedin an interview with Yves Saint Laurent and in several other fashionspreads as well {L'Uomo Vogue 1974: 152-5). Comparing the photo-graphs of models wearing Yves Saint Laurent and the dressing downof Andy Warhol there are similarities in chosen format and layout—four small images with different looks on one douhle page. There are,however, important differences to be found: while the models utilizedistinctly lazy male poses (hands in the pockets, cigarette in the hand),Andy Warhol conducts himself in a more feminine way. He is shownwith his arms crossed behind his head—a pose also to be found in oneof Marisol Escobar's images. Warhol does not, however, become a pas-sive model: he holds a camera in his hand and in the layout it appears asif he is photographing himself—he is simultaneously the photographingsubject and the object of his own camera.

In order to clarify the different conditions for male and female art-ists to become modeis, a look at the original presenters of fashion is inits place. Susanne Holschbach has shown how today's fashion poses

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 17

Figure 5Andy Warhol in LVomo Vogue, February/March 1974: 126-7, photographs by Oliviero Toscani, Courtesy of OlivieroTosoani,

have been developed out of actresses' stage poses in the nineteenth cen-tury. They were accustomed to striking and holding them, an impor-tant ability for fashion photography in early magazines (Holschbach2006).-" But even as a frozen pose was not necessary anymore due tothe new technical possibilities in photography, they remained fashionmagazines' favorite models. They offer possibilities for identification intwo directions: The (good-looking) actress is easily recognizable, whichprompts interest in her clothing. And further since the actress as fashionmodel takes on a role, the piece of clothing can also be imagined forthe reader's own roles. The actress is therefore especially suitable tomodel the (female) person because she fulfills a double postulate; i.e.she can embody individuality and diversity simultaneously—and this,according to Roland Barthes, is exactly the quality that is characteristicfor the successful presentation of fashion (Barthes 1990: 261). It seemsthat in the early 1960s Marisol could not model on the catwalk as anartist, because her profession, as opposed to that of being an actress, is

18 Antje Krause-Wahl

tied to an identity that is in conflict with the socially acceptable femaleroles. In order to let herself become a role model for the readers of thefashion magazine, she has to be "disconnected" from her work. Warhol,on the contrary, steps into the place of the actress and takes on differentgender roles, too—a technique that is comparable to his own artisticpractice, where he puts himself on display constantly with a camera.̂ ^Thus he was showing a clearly changed image of the artist. But in re-flexively staging this game he goes even further. In L'Uomo Vogue, theartist presents the act of working on one's own image as an ideal for themale reader. Unlike the usual presentations where successful men wearfashion, in the fashion spread by Toscani Andy Warhol surpasses thesuggested connection between fashion and the creative self. He presentshimself as someone who creates himself in and with fashion.

Modeling Success

Whereas Warhol in the example above displays different fashion brands,in other spreads he is only wearing Yves Saint Laurent [L'Uomo Vogue1975: 148, photographer Helmut Newton}." This strong connectionbetween a designer label that stands in for a special lifestyle and anartist can he found today with Tracey Emin and Vivienne Westwood.In April 2004 Tracey Emin was shown in British Vogue under the head-line "Indecent Exposure" (Picardie 2001: 254-61, photographer JulianBroad). In the article's main photograph the artist is depicted in a bath-room (Figure 6). She wears a silk and brocade dress with a high slit,high-heeled shoes by Vivienne Westwood and knee-high net stockings.The prices of the dress and accessories can be found in the text next tothe image. With her left hand placed on her thigh Emin pulls the dressa little upwards. The photograph gives the impression that she has justchanged her outfit, as discarded clothes are lying on the floor at herfeet. In her right hand the artist holds a delayed action release and sheapparently looks into a mirror, which is outside the image frame. Bymaking visible the technical device and having a controlling eye onthe image, Emin, like Warhol, claims hoth subject and object status.She takes on a clichéd seductive pose, while she demonstrates that sheknows that for sure.^' In the accompanying article, which is illustratedwith several of her works, Emin is portrayed as a successful artist.Again a good-looking woman artist is posing as a model—but in thiscase there is no conflict between good looks and artistic production.Here too, a transformation is staged—but Emin is not slipping intodifferent social roles; she wears a label that fits to her image as womanand artist with unconventional attitudes. The expensive designer dressis the result of hard work. Dressing up in her bathroom, she might be-come a role model for the readers, as she lets them imagine their owntransformation.

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 1 9

EXPC6LPJBanr^ her body and soul in the name of art,

Tracey Emin has never shed away from the shockingrevelation.But can her pan-fueletí confessions continue m

the wake of fwr success' Justne Rcarde meets Bntart'sfavounte exhibitioncst.Photographed by Jiian Broad

Figure 6Tracey Emm in British Vogue. April 2001: 254-5, photograph by Julian Broad, Courtesy of Julian Broad/Vogue.

Even if Vogue and Harper's Bazaar have a focus on art, their mainpurpose is to present fashion. In the last years several new magazinesreport on fashion and art more equally. Purple Fashion was launchedin 2004, emerging out of the magazine Purple founded in 1992 by agroup of young critics, artists, and curators. The editors wanted to giveartists an opportunity to present their work and build up a network forthe exchange of information hetween different disciplines (see www.purple.fr/). Purple Fashion is published twice a year in keeping withthe seasonal changes of fashion and it contains interviews with artistsand theorists and fashion spreads by internationally well-known pho-tographers, who are active in both the field of art and fashion. In theAutumn/Winter 2004-5 issue the artist Elizabeth Peyton was modeling{Purple Fashion 2004-5: 114-23; Figure 7). Posing in a bourgeois villa,in its garden, in a studio, in the forest and by the sea she wears clothesby Miu Miu, Dolce & Gabbana, Yohji Yamamoto, Marc Jacobs, andMartin Margiela. What "Elizabeth" wears is barely described, whereto buy the clothes is not mentioned at all. The photographs by An-nette Aurell are very different from the shrill fashion presentations in

20 Antje Krause-Wahl

Figure 7Elizabeth Peyton In Pt/fp/eFas/ïibn, no. 2, ALrtumnA/Vinter2004-5, pp. 120-1, photographs by Annette Aurell. Courtesy of Pu/pteFashion Magazine.

the magazine: They still have bits of Scotch tape attached to them, sug-gesting that the Ektachromes are put directly onto the paper withouthaving been worked over first. This signalizes that here we are dealingwith a portrait of an artist, the snapshot-like unsharpness of the firstphotograph, implies that Peyton is not posing in designer clothes, hutmerely wearing her everyday outfits. Made in black and white and obvi-ously in a format that is standard for the professional photographing ofartworks as well furthermore elevates the photographs in relation to theother fashion presentations in the issue. Fashion is again linked to art,but now it is the photographic style that infuses the fashion witb a time-less modernity, a value, that is somehow contrary to the ever-changingand avant-garde style in fashion.

But the photograph of Peyton working in her studio, placed betweenher images as a model, stands in visible contrast to her fashion pre-sentations as well. In a slovenly put on T-shirt she is sitting in deepconcentration in front of an easel with an unfinished painting. Nextto the brushes, a mobile phone appears, ready to be used. As in the

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 21

photograph of Tracey Emin personal success is linked to designer labelsthrough the "slipping into designer clothes," but here the story is told inthe order of the pages. But this is not the only difference: Unlike Vogue.,Purple Fashion serves a group of consumers for whom tbe crossoverof the fields of art and fashion has become a matter of course and whoknows who Elizabeth Peyton is. The usage of her first name does not somuch identify her as a model as it suggests a familiarity within the es-tablished network. The desk with easel and mohile phone also lets one'sown curatorial or critical activity imagine as one that justifies appearingin certain brands of designer clothes, which however are not only obvi-ously fashionable, but promise a timeless modernity.'''

"To Model" as a Project

Within the much-discussed crossover between art and fashion art-ists do not only model in fashion magazines, the wearing of fashionalso becomes an artistic project in itself. For Harper's Bazaar in 1993Cindy Sherman used her technique of masquerade to, in an ohviouslyexaggerated way, stage clothes by John Galliano and Calvin Klein andto question poses in fashion photography (Lewis 1993: 144-9)."

Less known, hecause less obvious, is a fashion-art shoot in a L'UomoVogue issue in 2000 titled "Artists. On Location" (Casadio 2000: 104-9, photographer Armin Linke)." It was made on the occasion of the"Carihhean Biennial," a fake biennial, staged by Jens Hoffmann andMaurizio Cattelan, who invited famous artists to a Carihhean island, todo nothing. The adverts for the biennial in various art magazines andthe press coverage, such as here in VUomo Vogue, became the "real"project. On the first page Rirkrit Tiravanija and Tobias Rehherger arephotographed standing at the water's edge, paraphrasing the romantictopic of the back view. The text informs the reader that they both aredressed in Tommy Hilfiger. Another page shows Vanessa Beecroft in ashirt by Diesel, worn in such a manner that the prominent label appearsas an accessory, so that an explicit naming of it is no longer necessary.Likewise the label of Maurizio Cattelan's shirt, wrapped around hisbody, is easy to discern. Whereas the modeling Emin and Peyton werepresented still in the tradition of the studio portrait this spread high-lights the similarities between the fashion and the art system. Drawingattention to Paul Poiret and the French avant-garde Nancy Troy haspointed out in detail how a fashion designer used artistic strategies andvice versa to position him/herself in the likewise connected field of artand fashion (Troy 2002). Troy's important observation is how signatureand label intermingle, the signature is used hy designers to signal artisticindividuality, artists on the other hand use their signature as a lahel, sym-bolic capital and market value goes hand in hand. In L'Uomo Vogue thenames of the artists are supposed to guarantee the quality of a product.

22 Antje Krause-Wahl

be it an artwork or a piece of clothing. But the participants of the art-fashion spread comment on this—not so new but fashionable—connec-tion in an ironic way in asking for the difference between advertising for

fashion and advertising for fashionable art events.

Between the Studio and the Catwalk

My investigation into this extensive period of artists presence in fashionmagazines has shown that there are many facets between studio andcatwalk closely connected to changing ideas of tbe artist. In the begin-nitig, the presentation of artists and models posing with art served thepurpose of adding to the value of fashion and fashion photography.Continuing the traditional idea of male productivity, artists were madeto exemplify a potential that the female readers should take on in thecreative design of their own looks or their environment. In this respectthe creative (female) artist seems especially suitable to be a role modelfor self-design: in the early 1960s this meant, though, entering into dif-ferent social roles by way of one's clothing. To be able to pose as amodel with whom the female readers could identify, the profession ofthe artist had to step into the background. In magazines aimed at a maleaudience, on the other hand, the merging of artist and model is lessproblematic. On the contrary: wearing fashion becomes a possibilitynot only to advertise a look, but also to play with the gender roles in aself-conscious creation of the self.

Isabelle Graw, looking closely at the correspondences between the fash-ion and art system, sees in the promise of fashion—the possibility to alwaysreinvent oneself—a framework that today both artistic practices and self-constructions are influenced by (Graw 2004: 83). It is Andy Warhol whointroduced this performative self-design into the fashion magazine, linkingreflexive self-invention to artistic creativity. In this way, traditional genderpatterns in the visual arts become disrupted as well and this opens the wayfor the presentation of female artists in fashion magazines. But in view ofthe observation above, the question concerning implicit gender hierarchiesis still present: whereas Warhol plays with his self-staging, making thefashion presentation an image of his self-creation, it seems that the expen-sive clothes of Emin and Peyton are a reward for their success. In currentfashion magazines more and more artists and fashion brands go hand inhand, but differences can be found as well, taking into consideration thedifferent audiences of the magazines. Compared to traditional magazinesa crossover product like Purple Fashion aims itself at both fashion and artinterested readerships. The strategy of mutual exchange, already found inthe photographs of models with artworks, now characterizes the wholeproduct. The fashion spreads in which fashion and artists are staged re-flexively show that artists are very aware of this process. Whether this can

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 2 3

be seen as a critique remains an open question, but it does have a parallelin the self-reflexivity of current fashion design and presentation.

In the period investigated, fashion magazines focus on artists withdifferent desires. The fashion magazine assigns a creative potential tothe artist, which first and foremost is connected to their work in thestudio but which extends to include the self-creation and reflection ofthe artist's own role. This twofold creativity is variously staged, makingthe artists attractive to the readers and finally setting out a role modelfor them "on the catwalk."

Notes

Every effort has been made to obtain permission for images reproducedin this article. If any omission has been made, please contact the pub-lisher, who will be glad to rectify this in future editions.

l.In the British magazine Î0+ (Spring/Summer 2006 S. 86-109) amodel poses after performances of Joseph Beuys. Photographer:Serge Leblon; Fashion Design: Nancy Rohde.

2. This study is part of a research project that focused on the multi-layered connection between art and the fashion magazine: AhretaH2006).

3. See Evans and Thornton (1989). They are building upon theoriesof looking that are widely discussed in feminist critique. Because ofshifting concepts of the viewer, those are revisited in the last years(for instance: Lewis 1997), but nevertheless still useful to under-stand the process of identification via the gaze (Silverman 1996).

4. 1 refer to the German encyclopedia: Meyers EnzyklopädischesLexikon (1976: 364).

5. For examples, see Holschbach and Krause-Wahl (2006).6. In the 1940s Matisse is shown frequently in fashion magazines.

Compare the list in O'Brian {1999: 249).7. Also in British Vogue, June 1949. For a selection of Coffins studio

portraits including the image of Matisse, see Muir (1997). It is inter-esting, that other portraits commissioned by Vogue, that obviouslyeroticize the male artist, are printed in small size in Vogue only, ordid not go into print at all.

8. Looking at the following pages, it becomes clear, that Matisse is notphotographed like a romantic genius. Instead this role is turned overto Father Couturier, whose portrait In black and white by IrvingPenn follows the article. Couturier worked together with Matisse indesigning the church.

9. Katharina Sykora argues, that Liberman's photographs seek to imi-tate the organization of Matisse's paintings (Sykora 2005).

í

24 Antje Krause-Wahl

10. For a history of the interior decorator in relation to women maga-zines see McNeil (1994). He draws attention to a Vogue article onPicasso as decorator (British Vogue 1929: 41). To justify modern artwhich appears decorative the male genius is defined in oppositionto female practices, after World War II the term design leaves thefemale-associated decoration behind thus opening up a new domainfor male practitioners. The article on Matisse's "designing" exem-plifies those shifting concepts.

11. Amelia Jones has paid attention to clothing as part of the artistic"habitus" (Jones 1995).

12. The series was launched in August 1963. Further "Fashion Inde-pendents" are, for example: the critic and writer Mutsuko Nagare,who is referred to as the wife of the famous Japanese sculptureMasayuki Nagare {Harper's Bazaar 1964b: 124-7); Mrs RichardBodgett, "writer, clubwoman, New York interested in the arts"{Harper's Bazaar 1964a: 152-5); and Mrs Vernon Taylor, a success-ful ski athlete, who herself designs clothes (Harper's Bazaar 1964c;128-31).

13. Whiting has analyzed the appearance of Marisol Escobar in thepopular press in detail. I'm taking up her arguments with anotherfocus (Whiting 1997).

14. Looking at German women's magazines, Jutta Röser has shown,too, that in the 1970s new models of identity are introduced (Röser1992).

15. One of the characteristics of Harper's Bazaar during the art direc-torship of Alexey Brodovitch is an all-over layout concept that setsevery page into correspondence with one another.

16. That this conflict is especially one of the creative working womancan be seen in comparison with other "Fashion Independents." Thesportswoman is characterized as a freelanced designer, but MutsukoNagare is described as follows: "whose beauty is as soaring andchiselled as some of her husband's famous stone shapes." FrancesFollin (2004) has shown, that with the painter Bridget Riley imagesof the female artist in fashion magazine change, but Riley is notmodeling. But it is in the 1970s that Vogue featured reportages atsome length about female artists, presented in their studio in a simi-lar manner than her colleagues in the 1940s. For example, BarbaraRose. "American Great: Lee Krasner" (Rose 1972: 118-20, 154).Krasner is photographed by Irving Penn sitting in her studio in frontof her paintings, another black-and-white image shows her at work.Her husband is mentioned, but their equal status stressed: "JacksonPollock and I were painters ... Sometimes I cooked. Sometimes hecooked."

17. Regular reports on the artist in his studio can be found between1970 and 1972, for example: Michelangelo Pistoletto, Lucio delPezzo, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg.

Between Studio and Catwalk—Artists in Fashion Magazines 2 5

18. For the increasing modeling of Warhol in the 1980s, see Hainley(1998:42).

19. The year 1974 marked comeback of the suit, bringing to mind thefamous book of John T. MoUoy, Dress for Success (Molloy 1975).

20. Holschbach argues that the fashion pose can be fully understoodonly regarding this "media shift" from theater to photography(Holschbach 2006).

21. L'Uomo Vogue June/August 2007 has reprinted the original pho-tograph of the Warhol fashion shoot without the cuttings for thelayout. Andy Warhol holds not only the camera but also a taperecorder, another feature that characterizes his image.

22. Remarkable are the "shy" brackets in the headline.23. Ulrich Lehmann has shown in detail how the photograph in Vogue

and her modeling for Vivienne Westwood is part of the trademark"Tracey Emin" (Lehmann 2002).

24. This issue, a retrospective of the magazine itself, contains a col-lection by Nicolas Gesquière described as follows: "forceful andtimeless modernity and his ability to innovate from season toseason."

25. For a close reading, see Loreck (2002). Another example of a projectin Harper's Bazaar is in "The Eashionabie Barbara Kruger" (Harper'sBazaar 1994: 148-53).

26. You find the same photo in the accompanying book (Cautelan andHoffmann 2001), but without the brand name.

References

Ahr; Katharina, Susanne Holschbach and Antje Krause-Wahl (eds).2006. Erblätterte Identitäten. Mode—Kunst—Zeitschrift, Marburg:Jonas.

Alberoni, Francesco. 1974. "Ritorno al conservatorismo?" L'UomoVogue February/March: 122-7.

American Vogue, 1945. "Unclutter." American Vogue January 1:42-7.

Bailaster, Ros. 1991. Women's World: Ideology, Femininity and theWoman's Magazine. London: Macmillan.

Barthes, Roland. 1990. Die Sprache der Mode. Frankfurt am Main:Suhrkamp.

Bergstein, Mary. 1995. "The Artist in his Studio: Photography, Art, andthe Masculine Mystique." Oxford Art Journal 18(2): 45-58.

Bernier, Rosamond. 1949. "Matisse Designs a New Church." AmericanVogue February 15: 68-71, 100.

Bostnar, Nils. 2002. Männlichkeit und Werhung: Inszenierung, Bedeu-tung, Typologie. Kiel: Ludwig.

Breward, Christopher. 2003. Fashion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

26 Antje Krause-Wahi

British Vogue. 1929. "Picasso as Decorator." British Vogue April 17:41.

British Vogue. 1950. "Elegance." British VogHe January: 36-45.Cattelan, Maurizio and Jens Hoffmann. 2001. 6th International Carib-

bean Biennial. Dijon: Presses du Réel.Casadio, Mariuccia. 2000. "Artists: On Location." L'Uomo Vogue

May/June: 104-9.Craik, Jennifer. 1994. The Face of Fashion: Cultural Studies in Fashion.

London: Routtedge.Crewe, Ben. 2003. Representing Men. Oxford: Berg.Evans, Caroline and Minna Thornton. 1989. Women and Fashion: A

New Look. London; Quartet.Follin, Frances. 2004. Embodied Visions: Bridget Riley, Op Art and the

Sixties. London: Thames &C Hudson.Graw, Isabelle. 2004. "Der letzte Schrei: Üher modeförmige Kunst und

kunstförmige Mode." Texte zur Kunst 5(>: 80-95.Hainley, Bruce. 1997. "Model." In Mark Francis (ed.) The Warhol

Look—Glamour Style Fashion, pp. 39-44. München: Schirmer undMosel.

Harper's Bazaar. 1954. Harper's Bazaar May: 120-5.Harper's Bazaar. 1963a. "Good Theatre: The Man to Watch, and the

Clothes to Wear." Harper's Bazaar Octoher: 176-9.Harper's Bazaar. 1963h. Harper's Bazaar October: 198-201.Harper's Bazaar. 1964a. Harper's Bazaar February: 124-7.Harper's Bazaar. 1964h. Harper's Bazaar January: 152-5.Harper's Bazaar. 1964c. Harper's Bazaar December: 128-31.Harper's Bazaar. 1994. "The Fashionable Barbara Kruger." Harper's

Bazaar FehTuary: 148-53.Holschbach, Susanne. 2006. Vom Ausdruck zur Pose: TheatraUtät

und Weiblichkeit in der Fotografie des 19. Jahrhunderts. Berlin:Reimer.

Holschbach, Susanne and Antje Krause-Wahl. 2006. "Mode und Avant-garde im Medienverbund Zeitschrift." In Katharina Ahr, SusanneHolschbach and Antje Krause-Wahl (eds) Erblätterte Identitäten,pp. 67-72. Mode—Kunst—Zeitschrift. Marburg: Jonas.

Jobiing, Paul. 2006. Fashion Spreads: Word and Image in FashionPhotography since 1980. Oxford: Berg.

Jones, Amelia. 1995. "'Clothes Make the Man': The Male Artist as aPerformative Function." Oxford Art Journal 18(2): 18-32.

Jones, Caroline. 1996. Machine in the Studio, Constructing the PostwarArtist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lehmann, Ulrich. 2002. "The Trademark Tracey Emin." In MandyMerck and Chris Townsend (eds) The Art of Tracey Emin., pp. 60-78.London: Thames Ik. Hudson.

Lewis, Jim. 1993. "The New Cindy Sherman Collection." Harper'sBazaar May. 144-9, 183.

Between Studio and Catwalk—^Artists in Fashion Magazines 2 7

Lewis, Reina. 1997. "Looking Good: The Lesbian Gaze and FashionImagery in Lifestyle Magazines." In Feminist Review 55: 92-109.

Liberman, Alexander. 1960. The Artist in His Studio. New York:Viking.

Loreck, Hanne. 2002. "De/constructing Fashion/Fashions of Decon-struction: Cindy Sherman's Fashion Photographs." Fashion Theory6(3): 255-75.

L'Uomo Vogue. 1969. LUomo Vogue no. 6.L'Uomo Vogue. 1972. "Andy Warhol & amici nella sua new factory."

L'Uomo Vogue April/May: 162-3.L'Vomo Vog^e. 1974. "Da parigi: Yves Saint Laurent, perché il clas-

sico?" L'Vomo Vogue February/March: 152-5.L'Uomo Vogue. 1975. "Andy Warhol (Dressed by Yves Saint Laurent)."

L'Uomo Vo^e January: 148.McNeil, Peter. 1994. "Designing Women: Gender, Sexuality and the In-

terior Decorator, c. 1890-1940." Art History 17(4): 631-57.Meyers Enzyklopädisches Lexikon. 1976. Meyers Enzyklopädisches

Lexikon in 25 Bänden, vol. 16, p. 364. Mannheim: BibliografischesInstitut.

Molloy, John T. 1975. Dress for Success. New York: Warner.Monopol. 2005. "For Beuys and Girls." Monopol no. 2, April/May: 84-9.Muir, Robin (ed.). 1996. Clifford Coffin. Photographs from Vogue

1945 to 1955. München: Schirmer/Mosel.O'Brian, John. 1999. Ruthless Hedonism: The American Reception of

Matisse. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Picardie, Justine. 2001. "Indecent Exposure." British Vogue April:

254-61.Purple Fashion. 2004-5. "Elizabeth Peyton: Portraits by Annette Au-

rell." Purple Fashion no. 2, Autumn/Winter: 114-23.Rabine, Leslie. 1994. "A Woman's Two Bodies: Fashion Magazines,

Consumerism, and Feminism." In Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferriss(eds) On Fashion. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Rose, Barbara. 1972. "American Great: Lee Krasner." American VogueJune: 118-20, 154.

Röser, Jutta. 1992. Frauenzeitschriften und weihlicher Lehenszusam-menhang: Themen, Konzepte und Leitbilder im sozialen Wandel.Opiaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Silverman, Kaja. 1996. The Threshold of the Visihle World. New York:Routledge.

Sykora, Katharina. 2005. "Auf den zweiten Blick. Henri Matisse unddie Fotografie." In Pia Müller-Tamm (ed.) Henri Matisse, Figur,Farbe. Raum, pp. 330-42. Ostfilder-Ruit: Hatje Cantz.

Troy, Nancy. 2002. Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art and Fash-ion. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Whiting, Cécile. 1997. A Taste for Pop: Pop Art, Gender, and Con-sumer Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.