PERSHING LLC (An Indirect Wholly ... - BNY Mellon | Pershing

ABE Illinois · Roscoe Pershing has the distinction of receiving the first Ph.D. that the U of I...

Transcript of ABE Illinois · Roscoe Pershing has the distinction of receiving the first Ph.D. that the U of I...

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 1

Greetings from Agricultural and Biological Engineering

Welcome to the latest issue of ABE@Illinois—this one

featuring then and now. Since assuming the position of

interim head this year, I have learned a great deal more about the

amazing work in which our faculty are currently involved. Our new

dean, Dr. Kim Kidwell, who joined us in November 2016, is a strong

proponent for ABE. She has challenged us as individuals and as a

department to articulate what we do and why it matters. Our faculty

were asked to document both of those, and it is uplifting to see the

wide scope and depth of activities in which we are making a differ-

ence both locally and internationally—ably representing the now!

The department’s almost 100 years of incredible accomplish-

ments are documented in two books (abe.illinois.edu/about/history).

Their narratives offer a remarkable record of activities that underpin

this great department—a reflection of then! Some of the articles in

this issue likewise document activities and achievements of our past.

My own path from then to now featured three six-month sabbatical visits from the University of

Kwa-Zulu-Natal in South Africa to the ABE department at Illinois. The visits, which took place at

five-year intervals starting in 1987, sowed the seeds that facilitated my applying for a position in

ABE in 1999, and ultimately my being chosen to fill it. As you will discover from reading through

ABE@Illinois, other faculty and alumni have had interesting and diverse paths from then to now.

One of our current students is even reaching for the moon!

As we prepare for the introduction of a new head of department later this year, I invite you to

provide us feedback. From your vantage point, what is working? What is not? And what should we

as a department consider addressing that will make a difference and ensure that we maintain

excellence? We value hearing your thoughts.

Best regards,

Alan Hansen

Interim Head

ABE@IllinoisAGRICULTURAL AND BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERING

Summer 2017

A

The refrain of a familiar folksong seems particularly appli-

cable to our department right now.The end of the 2016-17 academicyear came with significant changesto ABE. We saw valued membersof our small department leave, cur-rent members step up to fill voids,and new members bring excitingresources and fresh ideas.K.C. Ting was department head

of ABE from 2004 to 2016. K.C.retired from his position in Decem-ber 2016, and he is now the vicedean for academic affairs andstrategy at the Zhejiang UniversityInternational Campus in Haining,Zhejiang Province, China. K.C.helped our department celebrate75 years of agricultural engineer-ing degrees in 2009, and under hisleadership, we were four timesnamed the number one agriculturalengineering department in the nation by U.S. News and World Report.

The search for a new depart-ment head will begin this fall. Untilthen Alan Hansen is serving as interim department head; he wasappointed by ACES Dean Kim Kidwell in January. Al is one of ourmost respected professors, and hiswillingness to lead the departmentthrough this transition is greatly appreciated. He is head of the off-road equipment engineering group,and his most recent endeavor isproject lead of the AppropriateScale Mechanization Consortium.This group, funded by USAID,works in Bangladesh, Cambodia,Burkina Faso, and Ethiopia to helpsmall farmers learn how to growmore food while protecting the natural resources required for itsproduction.

Prasanta Kalita has been aprofessor in the ABE soil andwater division since 1999. In 2016,he took on the position of associ-ate dean of academic programs for the College of ACES. Prasantawill continue to teach Water in theGlobal Environment, a CampusHonors Program course.

Two new faculty members joinedour department this academic year.Girish Chowdhary is an assistantprofessor in Off-Road EquipmentEngineering and director of theDistributed Autonomous SystemsLab. His research interest is in

theoretical insights and practical algorithms for adaptive autonomy,with a particular application focuson field robotics and unmannedaerial systems. Neslihan Akdenizis a clinical assistant professor inBioenvironmental Engineering. Herextension and research interestsinclude livestock manure manage-ment, catastrophic animal mortalitymanagement, odor and air emis-sions from animal buildings, andanimal agriculture and climatechange adaptation.Scott Bretthauer, since 2003

an extension specialist with the

department in aerial applicationtechnology, led the Pesticide SafetyEducation Program (PSEP) until2016, when he left ABE for work inthe private sector. Matt Gill beganan internship with Scott in 2010,Matt’s freshman year as an agricul-tural engineering student. Heworked as an intern throughout hisundergraduate years and receivedhis bachelor’s degree in 2014. Hewill receive his master’s in late 2017.Matt was hired this year as an out-reach specialist and will head thePSEP program for the department.

Turn...turn...turn...ABE@ILLINOISSummer 2017

EDITORSMolly Bentsen

Anne Marie BooneLeanne Lucas

DESIGNPat Mayer

Published by the Departmentof Agricultural and BiologicalEngineering of the College ofAgricultural, Consumer andEnvironmental Sciences andthe College of Engineering at the University of Illinois at

Urbana Champaign

338 Agricultural EngineeringSciences Building

1304 W. Pennsylvania Ave.Urbana, IL 61801

Phone: (217) 333-3570Email: [email protected]

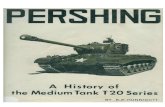

On the coverRoscoe Pershing, former ABEdepartment head and the first recipient of a Ph.D. inAgricultural Engineering at Illinois, is pictured with

Alejandra Botero Acosta, acurrent Ph.D. student in ABE.

Then and nowTurn. . . turn. . . turn. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Through the yearsAlumni from the last six decades give glimpses into the changes in life at Illinois—from then. . . ’til now . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

From precision ag to decision ag —making sense out of ‘big data’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Then and now . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Among the stars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Loren Maxey—Paying it forward . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

Past presidents of ASABE ABE alumni “lead the leaders” through service to professional society . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Giving back through the EAC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Girish Chowdhary

2

Roscoe Pershing, M.S. ’64 AgE, Ph.D. ’66 AgERoscoe Pershing has the distinction of receiving the first Ph.D. that

the U of I granted in agricultural engineering. The year was 1966; Pershing already had two degrees in the field, a bachelor’s from Purdueand a master’s from Illinois, but the Illinois Ph.D. was a near-miss.

“There was no Ph.D. program in ag engineering at that time,” Pershingsays, “so I was studying for a doctorate in theoretical and applied mechanics [TAM]. I was one or two courses short when the Ph.D. in ag engineering was established.” He transferred his coursework andcontinued his study of field data to predict tractor behavior on roadsideslopes from a mathematical model.

Computer modeling was much different in the mid-’60s, and Pershinghad to learn Fortran, the programming language that was the choice forengineering simulation. “I didn’t have time to take a course, so I boughtthe books and learned it in one weekend.”

Punch cards were the technology of the day, and Pershing wouldcarry boxes of them to north campus to run a program. “It was anovernight process, sometimes my program would say ‘AbEnd’—abnormal end. If I made one mistake or misspelling or forgot a comma,the whole thing failed, but I didn’t know it until the next day. It was prettyannoying.”

After finishing his doctorate, Pershing received multiple employmentoffers from industry and academia, including Ford, Deere, GE, TexasA&M, North Carolina State, Minnesota, and Illinois. Two paid internshipswith Deere and Company during his undergraduate years influenced hisdecision to accept a position as a senior research engineer. He spent19 years at Deere in research and development, service, marketing, andcorporate management.

In 1985, Pershing was asked to consider applying to be departmenthead in agricultural engineering at Illinois. He threw his hat in the ring.

Through the years

“I knew I had a great job back at Deere, so when I came to Illinois to interview, I was pretty relaxed,” he says with a laugh. “I was amazed attheir offer. I’d done some part-time teaching at Black Hawk Collegewhile I was at Deere, but I didn’t really have an academic back-ground. They were going to give me tenure as a full professor. Thatwas pretty hard to turn down.”

When Pershing began as department head, there was no intro-ductory course for ag engineering, so he developed AgE 100 andtaught the class himself. “The students were surprised when the department head showed up to teach, but I wanted to get to know them. I wanted to use my industry background to help themunderstand engineering from the outside.”

One issue Pershing faced as head was the floundering agricul-tural mechanization program. “I was told to kill it or fix it. I decided tofix it. I asked everyone I knew, ‘Who’s the best guy in ag mech?’ Theanswer was always ‘Phil Buriak.’ So I recruited Phil, and he more thandoubled the number of students. Now it’s called Technical SystemsManagement [TSM], and it’s an amazing program.”

Other projects Pershing tackled included setting up a computerlab for students—and holding seminars to teach faculty to navigatethe fairly new technology.

Pershing left the department in 1993 to become associate deanfor academic programs in the College of Engineering, where he remained until his retirement in 2004.

Pershing’s interest in computing continues. “I meet with otheremeriti for breakfast every week, and I’m kind of the go-to guy fortheir tech questions. Someone will want to know if they can print remotely from their smartphone to their home printer, and I’ll say,‘Sure I’ll show you how.’ ”

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 3

Ruth Book, B.S. ’80 AgE, M.S. ’95 AgE, Ph.D. ’98 AgERuth Book was a U of I student in two very different periods.

She first came in 1976 to earn a bachelor’s degree in structures and environment. Computer technology had advanced since the1960s, but students still used punch cards to communicate with amainframe computer.

“I’d spend hours creating the code and transferring it to the punchcards,” Book says. “Today we have more computing power on ourphones than existed in that mainframe.”

Book returned to campus in the 1990s, earning a master’s and aPh.D. in off-road equipment. “The excitement for me at that time wasmechatronics, a blend of electronics and mechanical engineering.My particular interest was control systems for fluid power.”

The role of women in engineering was another difference Booksaw from the ’70s to the ’90s. “As far as I can recall, as an under-graduate I was the only woman in all of my engineering classes,” shesays. “When I returned in 1994, women were still in the minority, butthey were definitely a presence to be reckoned with. I see that as agood thing, and we’ve made even more progress since then.”

Book has worked as a design engineer with Cessna Fluid Power in Hutchinson, Kansas, and as a project engineer with EatonHydraulics in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. For the last 16 years she hasworked with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, as an agricultural engineer for four years and a resource conserva-tionist for two. For the last 10 years, she has been the state conservation engineer.

“I’ve changed direction in my career several times, gaining new interests and moving on. That’s what is so powerful about our ABEprogram at Illinois. It’s great preparation for whatever life might throwat you!”

Alumni from the last six decades give glimpses into the changes in life at Illinois—from then . . . ’til now.

“I’d spend hours creating the code and transferring it to the punch

cards,” Book says. “Today we have more computing power on our

phones than existed in that mainframe.”

“If I made one mistake or misspelling or forgot a comma,

the whole thing failed, but I didn’t know it until the next day. It

was pretty annoying.”

1970s

1960s

4 Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 5

Steve Ford, B.S. ’87 AgM“The advent of the personal computer was the major development

in the mid- to late 1980s,” Steve Ford says. “Even small companies in the agricultural equipment manufacturing sector had access to affordable CAD [computer-aided design] programs and CNC [computer numerically controlled] tools.”

“However,” he continues, “the computers and programs of that time were pretty much standalone, in contrast to today’s ‘connected’society.”

Ford points to a change in the student population since his time as an undergraduate. “Fewer ABE and TSM students have farm backgrounds today,” he says. And movies streamed on a computer orphone were far in the future. “At that time, showing movies was agreat way for the Ag Mech club to make money. Student organiza-tions could reserve a large lecture hall on campus and rent a film tobe shown on Friday or Saturday night. To Catch a Thief with CaryGrant was one I remember watching.”

After graduation, Ford worked with GSI–Grain Systems in engi-neering product development for three years. In 1990, he returned to the department to manage the BESS (Bioenvironmental and Structural Systems) Laboratory.

“The BESS Lab is to agricultural ventilation fans what the NebraskaTractor Test Lab is to tractors,” Ford says. “We measure airflow and energy efficacy of fans used in livestock housing and publish the datafor end users. I meet and work with people from all over the U.S., Europe, Asia, and Central and South America. It’s what I enjoy mostabout the job.”

When asked for a favorite memory of his time as an undergraduatein ABE, Ford had a quick answer: “Getting married to my great wifebetween my junior and senior years!”

Christopher Behme, B.S. ’94 AgM“Most significant in agriculture and the economy are the exponen-

tial changes in technology and how we manage it,” says Chris Behme.“The challenge has been to include security in those shifts and to understand how regulation impacts application of new technologies.”

After graduating from Illinois, Behme earned a master’s degree in ag mech from Texas A&M University. Today he is a partner andsouth-central cluster lead with IBM’s communication practice, focusedon innovation with North American utilities. Prior to joining IBM, he was a SunGard Global Services utilities lead and a client partneracross key accounts at Accenture. He was also employed at Dow-Elanco, a joint venture between Eli Lilly and Dow Chemical.

The overriding memory of his undergraduate years, Behme says,was the camaraderie in the department.

“Roscoe Pershing was the department head, and Phil Buriak ledthe ag mech section. Those two men made sure every single studentfelt like they had a home here. It was very easy to connect with facultyand other students in ABE.”

In fact, Behme says, a fellow ABE alum was present on one of themost important days of his life: “I proposed to my girlfriend Kelly, onthe Great Wall of China, and John Tuntland (BS ’99 AgE) guarded thetower so we wouldn’t be interrupted!”

Matt Robert, B.S. ’96 AgE, M.S. ’00, AgE“The biggest innovation coming out of ag engineering when I was in

college was GPS-driven tractors and equipment,” says Matt Robert.“It’s what everyone was talking about. Today GPS equipment can befound on every farm.”

“The improvements of gas detection and the measurement of airquality had the most impact on my career,” Robert continues, “since I was specializing in structures and environment. We could do measurements never before done on livestock sites.”

After working as an engineer for a swine building manufacturer, a visiting research engineer at Illinois, and a consultant for livestockproducers, Robert took his current position as agricultural engineer for USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“I review proposals and designs for producers in Illinois who hope toreceive funding to solve environmental problems on their site,” Robertsays. “I also design some of those facilities when necessary.”

Robert says being a problem solver is his favorite part of the job.“When I was a student I was taught structures and environment, powerand machinery, soil and water, and food processing. I did specialize in afield, but I really wasn’t an ‘expert’ in only one area. I didn’t realize howimportant it was for me to learn those basic principles in other areasuntil I was out working with farmers. They always have questions thatrequire me to use all the basic engineering principles taught in thoseclasses. I work with other ag engineers who graduated in the ’70s and’80s, and it’s great to see how well-rounded and versatile they are.”

Away from the job, Robert volunteers with the local Knights ofColumbus Council, and for the last 11 years he has done the PolarPlunge to raise money for Special Olympics.

Brian Jacobson, B.S. ’10, TSMBrian Jacobson has seen progress continue in automation in

manufacturing and ag production after coming to Illinois. “As a freshman, I worked at a company helping set up automated produc-tion equipment in a manufacturing facility,” Jacobson says. “I also remember seeing experimental ‘miniature aircraft’ and helicopters on the first floor of the ag engineering building.

“Today, production automation is almost required to be competitive,”he continues. “Those aircraft—now known as drones—are every-where, serving important commercial uses in agriculture and otherfields. Automation has even entered people’s personal lives through‘smart home’ devices that you can speak to.”

Another area Jacobson is excited about is using biological materialfor energy and consumer product production. “While corn ethanol hasbeen around for some time, new patents are being filed and productsdeveloped every day that greatly expand our ability to use biomass asa production input.”

Jacobson works in ACES as the manager for the FSHN (Food Science and Human Nutrition) and IBRL (Integrated BioprocessingResearch Laboratory) pilot plant facilities. His responsibilities includeoverseeing renovation and construction activities.

“The pilot plants are flexible facilities for teaching and for researchand development, so I’m constantly working on different problems andprojects, with different people, for different stakeholders. That changekeeps me motivated, and the large expansion in capabilities we willhave after all the construction is complete is very exciting.”

Jacobson spends his time off work with his wife and their two-year-old son, sometimes traveling west to visit friends on extended camp-ing trips in Wyoming. He also enjoys cooking for friends and familyand does a whole-hog roast at least once a year.

“The computers and programs of that time were pretty much standalone, in contrast to today’s‘connected’ society.”

“The improvements of gas detection and the measurement of

air quality had the most impact on my career.”

“The challenge has been to include security in those shiftsand to understand how regulation impacts application ofnew technologies.”

“I remember seeing experimental ‘miniature aircraft’ and

helicopters on the first floor of the ag engineering building.”

2010s2000s1980s 1990s

6

“ ‘Big data’is changing the world of agricul-ture as we know it,” says Chris Harbourt, ABE alumnus andCEO of Agrible, Inc. “Minute by minute, day by day the land-scape for growers and food companies is adjusting and react-ing based on data that companies like ours are presenting. We help both growers and companies utilize that information.”

Harbourt has been working since the mid-’90s to transformthe agriculture industry using big data. He founded Agrible in2012 to provide growers with tools to increase productivity, ef-ficiency, and sustainability. Agrible uses a variety of datasources to develop their products, Harbourt says, includinggovernment soils databases, atmospheric models that predictweather, and databases of historic weather as well as infor-mation gleaned from growers who use the company’s prod-ucts. To date, Agrible has produced six software products:Morning Farm Report, Find My Seed, Agrible Services, Pocket

Rain Gauge, Pocket Spray Smart, and Pocket Drone Control. “When it can be harnessed and used effectively, big data is a

useful tool, especially in the agriculture world. We’re making amove from what’s largely been called precision ag to whatwe’re now calling decision ag,” Harbourt says. “We take all ofthis information that’s called big data and turn it into somethinguseful, something that can increase the power of the informa-tion. We want to give growers insight into their operations tomake better decisions and make a profit.”

Agrible products address a variety of crops, including corn,soybean, winter and spring wheats, hard red and soft whitewheats, cotton, and peanuts. “We can predict yields for grow-ers,” Harbourt says. “They tell us what day and what seedthey’re going to plant, what fertilizer they’re going to put downand when. We can predict their yield before they’ve even en-tered the field.”

From precision ag to decision ag– making sense out of ‘big data’

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 7

Preparing students for ‘big’ futures

Scientists will tell you that the importance of big data isn’t howmuch data you have; it’s what you do with it that matters.Being able to examine and analyze large and varied data

sets is a skill that continues to increase in importance.To meet this need, Luis Rodriguez, an associate professor in

ABE, has developed the Food and Agriculture Big Data (FAB) Fellowship Program. “Before now, our ability to create people whowere ready to work in the area of big data was limited but growing.The FAB Fellowship expands on that growth. It will be an effectivecredential that demonstrates the depth of a student’s training infood and agriculture, big data, and the ability to analyze complexsystems,” Rodriguez says.

The program is recruiting first- and second-year students whowill take courses in computing, statistics, and data analysis as wellas participate in laboratory research, pursue study abroad opportu-nities, and participate in international industrial immersion.

The FAB Fellowship is part of a USDA National Institute of Foodand Agriculture grant that funds the DIFM—Data-Intensive FarmManagement—program. The interdisciplinary DIFM uses precisionagriculture technologies to run full-field, on-farm agronomic trialsthat change application rates of nitrogen fertilizer. David Bullock, aU of I agricultural economist, is the project’s principal investigator,and Rodriguez is one of 28 researchers and extension personnelfrom six universities who coordinate the on-farm experimentsacross 100 fields in Illinois, Nebraska, Kentucky, Argentina, andUruguay.

Because this study will generate substantial data, Rodriguez andhis colleagues felt it was important to take a strategic and more ho-listic approach to preparing students to work with big data. He hasrecruited five first- and second-year students who have expressedan interest in developing their computational skills as well as theirunderstanding of food and agriculture.

“Somewhere along the line, they picked up the idea that thereare real opportunities here,” Rodriguez says. “This program will bol-ster their undergraduate education in a way that will put them in abetter position down the line to contribute to the field at an entrylevel, whether that’s graduate education or industry.”

Agrible’s predictions are impressive in their accuracy. “We’re limitedonly by the accuracy of the weather forecast, but even in outside cases,we come within five percent,” Harbourt notes. “When we get to the endof a season and all the weather has occurred, our models are almost anexact match with the yields growers see coming out of the field.”

Agrible has more than 7,000 clients in 86 countries and 48 states,with a large presence in both the U.S. and Brazil. The company beganwith two people and now has more than 60 employees. “There’s an inter-esting social piece to the company,” Harbourt says. “I have employeesthat are 16 all the way up to 70. One of our app developers is 16—a bril-liant kid. Then we have employees who are the same age as the averagegrower today—they’re still interested in staying engaged in new technol-ogy and want to have fun.”

Harbourt received his master’s degree and his Ph.D. in agricultural engineering from the department in 1999 and 2002, respectively. Theblack-and-white photo shows Harbourt as a graduate student workingon a computer that he says had less power than the average tablet usedtoday. “I’m sitting there pulling data together and trying to analyze oneday of storm information. It took me a year and a half. That was my wholemaster’s program. Now Agrible’s Pocket Rain Gauge gets 30,000 to40,000 uses a day, and at each of those locations, it’s doing more calcu-lations than I did in my master’s degree. And it’s free. The democratiza-tion of technology has been quite amazing.”

The rate of technology increase is so astounding that it’s almost im-possible to know where agriculture will be 10 years from now, Harbourtsays. “What you need to keep in mind is that we are in a nearly optimizedsituation in the U.S. There’s not a whole lot many growers can do betterexcept remove some of the variability around the weather and thingsthey can’t control directly. That’s where Agrible comes in; we help grow-ers streamline operations so they’re maximizing yields responsibly ontheir farms.

“I think we’ll see the greatest strides in agriculture and data sciencewhen we take what we’ve learned in the U.S. to someplace like India,” hecontinues. “Crop failure for them is a three- or five-year event. Completefailure every three to five years. What do we see here in the U.S.— onefailure every 20 years, maybe? And even then it’s not a true failure, it justmeans the year’s not profitable. So I hope we’re going to see great appli-cations of knowledge to areas that really didn’t have access to it before.That should be the next revolution in agriculture.”

Luis Rodriguez (far right), professor in ABE, with the first recipients of the FAB Fellowship,left to right: Aiden Kamber, Maddie Poole, Brady Winkler, Raagini Gupta, and Elisa Kim.

1999 2017

The Pocket Rain Gauge™provides accurate,

location-specific rainfallmeasurements.

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 98

2017Angela Green is the firsttenured female professor inthe Department of ABE.

1867The Illinois General Assemblypasses a bill authorizing the creation of the Illinois IndustrialUniversity. John Milton Gregoryis the first regent.

1885Illinois Industrial Universityis renamed the Universityof Illinois.

1900The Division of Farm Mechanics(the original name for our department) isformed in the Department of Agronomyin the College of Agriculture.

1904The first Bachelor of Science degree in Agricultural Mechanization is awarded to Charles A. Ocock.

1921The discipline of agricultural engineering separates from the Department ofAgronomy as part of a new Department of Farm Mechanics. The first head of the new department isEmil W. Lehmann.

1932The department namebecomes AgriculturalEngineering.

In 2017, we mark the sesquicentennial anniversary of the University of Illinois. The Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering has been an integral part of ouruniversity’s 150 years—albeit under several names. Let us share just a few highlights…

1934The Illinois Student Branch ofthe American Society ofAgricultural Engineers holdsits first meeting on October 9.

1934The first Bachelor of Sciencedegree in Agricultural Engineering is awarded to H. Paul Bateman, who joinsthe faculty and serves untilhis retirement in 1968.

1960The Illini AgriculturalMechanization Clubis established.

1955Frank B. Lanham is named thesecond department head of Agricultural Engineering.

1978Roger R. Yoerger is namedthe third department head of Agricultural Engineering.

1966Roscoe Pershingbecomes the first Ph.D. recipient in the Departmentof Agricultural Engineering.

1985Roscoe Pershing is namedthe fourth department headof Agricultural Engineering.

1983The department moves tothe new AgriculturalEngineering SciencesBuilding at 1304 W.Pennsylvania, Urbana.

1994Loren Bode is named thefifth department head ofAgricultural Engineering.

1994The Department of Agricultural Engineeringachieves its first #1 national ranking in asurvey published by U.S. News and WorldReport. The department goes on to earn the#1 ranking four more times and remain inthe top five nationally.

2003Agricultural and Biological Engineeringis adopted as the new department name to reflect changes in the discipline as food, environmental, and energy systems begin to play a significant role in our economy.

1996The degree in AgriculturalMechanization is renamed Technical Systems Management.

2011The Technical Systems Management program offers students their first opportunity to earn a master’s degree.

2004K.C. Ting, Ph.D. ’80 AgE, is named thesixth department head of Agriculturaland Biological Engineering.

2013The state’s Capital DevelopmentBoard designates $20 million tobuild the Integrated BioprocessingResearch Laboratory (IBRL) onthe ACES campus. ABE professorDr. Vijay Singh is later named director of IBRL.

2012Yuanhui Zhang, professor in ABE, isinvested as the Innoventor Professorin Engineering, the first named chairin the Department of ABE.

Then and now

Timeline photos (left to right): a) First building on the Illinois Industrial University campus. b) Ag engineers demonstrate surveying skills in 1913. c) Engine short course in 1920.d) Al Jensen, Ed Hansen and Art Muehling discuss plans for the Moorman Research Farms. e) Emerti professors conduct their own groundbreaking as the AESB project gets underway on May 26, 1981.f) Roar Irgens led the way in the aerobic research program. g) Carroll Goering adjusts a dual fuel tractor engine that burns either ethanol or diesel fuel. h) Architectural drawing for IBRL.

a b c d e f g h

1867 2017

1948Barbara Jordan is the firstwoman to receive a bachelor’sdegree in the Department of Agricultural Engineering.

among the Stars. 10

Shoot for the

moon and even

if you miss,

you will land

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 11

While many new university students spend theirfirst year largely adjusting to college life, AlexDarragh, a freshman in ABE, decided to

shoot for the moon. Literally.Darragh and Matt Steinlauf, a freshman in mechani-

cal engineering, entered the Lab2Moon Challenge, an international competition sponsored by TeamIndus,an aerospace research organization. The competition required students to design and build an experimentthat would help develop sustainable life on the moon.TeamIndus would manufacture the winning design andinclude it on a voyage to the moon in December of 2017.

The aspiring engineers designed a miniature green-house enabling humans to grow crops in lunar soil.About the size of a beverage can and weighing lessthan half a pound, the galactic greenhouse has anArchimedes’ screw that drills into the ground, lifts lunarsoil (also called regolith), and drops it into rotating cupsinside the device. When the screw retracts, the holecloses, and the device pressurizes, heats up, and exposes the regolith to atmospheric gases includingoxygen and nitrogen. Tubes deposit seeds, water, andfertilizer into the cups, and once a plant starts to grow, itis monitored by sensors and a camera.

Because lunar soil lacks nitrogen, the team chose togrow blue lupine, a bean that takes nitrogen from the air.The idea is to introduce nitrogen and other fertilizers at various levels and gather data to determine which fertilizers will be the most effective.Regolith Revolution, the Darragh/Steinlauf team, grew the bean in regolith simulant, a form of crushed volcanic ash.

“We tested different fertilizer solutions to find the one that workedbest with lunar soils and plants to minimize the amount of nutrients youwould have to bring to the moon,” Darragh says. “The blue lupine grewextremely well.”

TeamIndus is one of five privately held companies traveling to themoon in December, hoping to win the Google Lunar XPrize, a globalcompetition to challenge and inspire engineers and entrepreneurs to develop low-cost methods of robotic space exploration. To win the $30-million prize, a privately funded team must successfully place a robot on the moon, travel at least 500 meters, and transmit high-definition video and images back to earth.

To increase opportunities for lunar research,TeamIndus developed the Lab2Moon Challenge,which spurred entries from more than 3,000teams in 15 countries.

The second phase of the competition nar-rowed the field to 25 teams. Regolith Revolutionwas one of three teams from the United Statesto make the cut. Several teams were from India,and the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, and Mexico were also represented.

Of the 25 teams, 15 traveled to Bangalore,India, in March to present their designs to TeamIndus. Judges narrowed the field to seventeams qualified to join the mission—includingRegolith Revolution.

The final challenge for each of the seventeams was to raise $750,000 to pay for the experiment. Darragh says he and Steinlauf wereunsuccessful in securing the required fundingby the deadline.

Prasanta Kalita, a professor of agricultural engineering and associate dean of academicservices in the College of ACES, was a sponsorfor the team. He gave the competitors labora-tory space and connected them with a lab assis-tant and other Illinois professors. He has nothing

but praise for the young inventors.“We live in a world where our greatest problem will be feeding nine

billion people by the year 2050,” Kalita says. “We won’t have enoughfood, so here are two students who come up with the idea of growingfood on the moon. They have never faced hunger, yet they wanted to do something. They had the background and the ability, and they weretotally dedicated. I think it was a remarkable effort.”

Although Darragh had hoped for a different outcome, he concludes,“This has been an amazing experience as an aspiring engineer. It wasgreat to be part of a project that has so much potential.”

The state-run Indian Space Research Organization will launch the TeamIndus spacecraft from Andhra Pradesh in late December.

[left] Greenhouse plant grown in regolith.[center] Shell of galactic greenhouse.[right] Alex Darragh works in the lab[bottom] Alex Darragh, left, and Matt Steinlauf qualify for the Lab2Moon mission.

“We tested different fertilizer solutions to find the one that workedbest with lunar soils and plants to

minimize the amount of nutrients youwould have to bring to the moon.”

“

”

Les Brown

After facing his own financialchallenges to higher educa-tion last century, ABE alum-

nus Loren Maxey is turning someof the fruits of his education andcareer to helping the students oftoday.

Loren Maxey was born in 1932at home on a farm near Polo, Illinois. He was the first baby everdelivered by the young doctor,who arrived at the house in asleigh (it was early March and theroads were drifted shut). Also bornon the farm were an older andyounger brother and twin sisters.A “tagalong” brother came later,after the family had moved to adairy farm near Freeport, Illinois.

Like all farm kids, Maxey did avariety of jobs, including field workand caring for hogs, chickens,sheep, and horses. Later, in the

early years of World War II, hehelped his father install electricalwiring on farms. “Now and then, afarmer had a little leftover materialfrom wiring the barn,” Maxey says,“so he’d ask if we could put in ayard light or house outlets ‘whilewe were there.’ ”

With that training and someFFA classwork, Maxey competedfor and won FFA electrificationawards at the state, regional andnational levels. “The award moneypaid my first-semester tuition atIllinois State University in the fall of 1950,” Maxey says. “But the Korean War was on, and I had nofunds for a second semester, so I joined the Navy.”

Maxey became an electrician’smate on the USS Shea (DM-30).Ship operations took the crew toEngland, Ireland, Portugal,

Panama, the Virgin Islands, Cuba,and Puerto Rico, as well to as anumber of stateside ports.

From its original base inCharleston, South Carolina, theShea was transferred to LongBeach, California, in 1954. “To oursurprise,” Maxey says, “we loadeda full cargo of over 100 activemines and took them to the hy-drogen bomb test site in the Mar-shall Islands. We laid the mines ina quarter-mile circle outward from

the bomb barge tied to asandbar.

“We were 12 miles out from theblast site at 6 p.m. when the bombwent off. I was topside and got toturn and see the mushroom cloudtwo minutes after the blast.”

Maxey advanced quickly topetty officer, first class and be-came friends with the three engi-neering officers on the ship.“That’s when I knew I wanted topursue ag engineering at Illinois

12

Loren Maxey – Paying it forward

Loren Maxey during his first week of school at the University of Illinois.

“The award money paid my first-semester tuition at Illinois StateUniversity in the fall of 1950, but the Korean War was on, and I had

no funds for a second semester, so I joined the Navy.”

This year, with a desire to help others “move on to that engineering future,” Maxey established the Loren R. Maxey Scholarship, which will give tuition assistance to third-year students in ABE.

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 13

when I was discharged,” Maxeysays.

The Navy released him a monthearly to allow him to get started at the University of Illinois in January of 1955. The GI Bill paidhis tuition, and college credits fromISU and several correspondentcourses he took during his enlist-ment enabled Maxey to enroll as a sophomore.

“I first stayed with my brother-in-law’s parents while I looked forstudent housing and supplementalwork,” Maxey says. “I was about tomove to the landing of a stairwayin a rooming house and take a jobserving tables at a sorority. My ad-visor, Howard Wakeland, called totell me that the department headof agricultural engineering, EmilLehmann, wanted to see me.”

Lehmann, known for helpingstudents find ways through eco-nomic hardship, had a basementroom with a separate entranceand shower facilities in his largehouse. He offered Maxey rent andtwo meals a day in exchange forhis help with a variety of projectsaround the property.

Maxey knew it was a goodarrangement, “but I had to explainthat at least once a month andover breaks, I planned to go hometo Freeport, and I was engaged tobe married at the end of July.”

Once the details were workedout, Maxey moved to his basementroom in the Lehmann home. Over the next several months, he helped convert a closet to a

half-bath, drilled a new well, converted a chicken house to aworkshop, planted shrubs andtrees in the small nurseryLehmann owned, and sold nurserystock to weekend customers.

Maxey must have impressedLehmann with his work ethic, be-cause “that’s when the best thinghappened. Dr. Lehmann wanted toknow if I would be interested instaying on during the summer toturn a small, older farmhouse atthe back of the property into livingquarters for me and my bride-to-be.” Lehmann was retiring from Illinois in the fall and would betraveling for a different teachingposition, so the new arrangementwould include helping Mrs.

Lehmann during the professor’sabsence and taking over manage-ment of the nursery.

Maxey began work on thehouse in June, taking two weeksoff for a honeymoon in July. Thenewlyweds came back to Urbanaand rented a small apartment forsix weeks. By the start of theschool year, the lower level of thehouse was insulated, the outerwalls were finished, applianceswere in, and the bath was func-tional. “We moved in with sheetson the inside walls and a bed inthe unfinished living room. Whenwe moved out, the house, the yard,and the garage were finished andready for the next occupants.”

Because of his friendship withthe Lehmanns, Maxey says hewas able to meet and interact with many other staff and facultymembers, including Frank Lanham, a future ag engineeringdepartment head; Ben Jones, afaculty member who would bewith the department for 40 years;Hoyle Puckett, the research

engineer who supervised Maxey’ssenior project; and Frank Andrews,the ag engineering extension specialist in farm electrification. “It was a fantastic three years,”Maxey says.

Maxey graduated with a degreein agricultural farm mechanizationin 1958. Over the next 10 years,he worked as a draftsman for anairplane manufacturer, nationalcustomer service manager for an arc welder manufacturer, andengineering manager of a sugarbeet equipment company. Hestarted his own manufacturingcompany in 1969 to build irriga-tion sprinklers for turf grass farms.Maxey Companies evolved over45 years, building truck bodies,equipment trailers, and snowgrooming equipment for ski areasand snowmobile trails.

This year, with a desire to helpothers “move on to that engineer-ing future,” Maxey established theLoren R. Maxey Scholarship, whichwill give tuition assistance to third-year students in ABE.

“That’s when the best thing happened. Dr. Lehmann wanted to knowif I would be interested in staying on during the summer to turn a small, older farmhouse at the back of the property into living

quarters for me and my bride-to-be.”

“I was about to move to thelanding of a stairway in arooming house and take a job serving tables at

a sorority.”

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 15

Douglas Bosworth

Robert G

ustafson

Larry Huggins

ABE faculty and alumni who have served ASABE as presidents

Charles A. Ocock, ’04 1911–12

Earl A. White, ’08 1921–22

Emil W. Lehmann 1923–24

Glen W. McCuen, ’15 1934–35

Karl J.T. Ekblaw 1939–40

Frank B. Lanham 1976–77

Douglas L Bosworth, M.S. ’64 1992–93

Allen R. Rider, Ph.D. ’73 1996–97

Larry F. Huggins, M.S. ’62 1999–00

Lyle E. Stephens, M.S. ’68 2002–03

Robert J. Gustafson, M.S. ’72 2003–04

For 100 years, agricultural and biological engineers around our countryand the world have looked to their professional society for leadership and support. Founded in 1907 by J. Brownlee Davidson, the American

Society of Agricultural Engineers boasted 18 charter members, including EarlA. White, University of Illinois student and center on the football team. Whitewould later become president of the Society. Today the expanded AmericanSociety of Agricultural and Biological Engineers has over 9,000 members in more than 100 countries. Contributors to the organization’s long and distinguished history include 11 from our department who have served the society as presidents. Three are alumni Doug Bosworth, M.S. ’64, Larry Huggins, M.S. ’62, and

Robert Gustafson, B.S. ’71, M.S. ’72. Bosworth was president of ASABE in1993–94, Huggins in 1999–2000, and Gustafson in 2003–2004. Each tooktime to share some of their experiences as president and their thoughts onchanges in their discipline over the years.

Q&APast presidents of ASABE ABE alumni “lead the leaders” through service to professional society

“There will be no ‘leveling off’ of engineering in this field as population growth continues, demands for more nutritious foods grow, and resources to produce food, fiber, and energy become limited.”

14

Q. What was new in the discipline at the time of your tenure? Douglas Bosworth – “The early 1990s had seen the increased use of electronics and satellite technology that was being labeled‘precision farming.’ The growth in this part of agricultural engineeringhas been phenomenal in increasing productivity, safety, and efficiencyof agricultural production. Members of ASABE are leaders in thistechnology, and many are graduates of our programs.”

Larry Huggins – “The big issue was about the future role of biologicalengineering and how to integrate it into the profession without offending the ‘traditional’ subdisciplines. In particular, changing the society’s name was becoming a major, multiyear issue. And the rapidlyemerging availability of low-cost, powerful computers was the majortechnology impacting not only our professional practices, but everyaspect of society.”

Robert Gustafson – “I think the way we accessed information, and other people, affected how we practiced engineering. Electronicaccess to information and people via the Internet was an amazing resource. But it came with a higher level of responsibility to be able to interpret and apply the information. I think this made the practice of engineering more dynamic, interesting, and even more fun.”

Q. What was your most significant achievement and yourgreatest challenge during your tenure?Bosworth – “In my position at John Deere, we were moving from a traditional hierarchical organization to a team-based organization. My initial goal in ASABE was to develop a team environment at head-quarters. I took several Deere workshops to ASABE headquarters for staff development and training. The result was favorable, and thestaff self-developed into a team structure. This was also the time when the organization changed from a semiannual to annual meetings.Since this broke with tradition, there were obstacles, but one excellentmeeting per year was accepted as a good model.”

Huggins – “I had the benefit of having served on and chaired the Finance Committee before becoming president, so the most signifi-cant achievement was improving the financial undergirding for the society. Growing our foundation’s endowment was a significant long-term component of the improvement. Challenges we faced included struggles with building our international membership andrecognition. The society also grappled with how to help academic departments increase enrollments.”

Gustafson – “I think the biggest challenge we faced [and success-fully addressed] during my term was a name change for the society. A name reflects many things to current members and projects a significant message to potential members and the public. Althoughwe considered a number of names that would reflect the current and desired nature of the society, I was pleased that members ralliedaround picking a name that would best serve the future of the society.”

Q. What role do you see for ag and bio engineering in addressing some of the problems society faces?Bosworth – “The entire scope of production agriculture and the industries that serve agriculture has little resemblance to that of 20years ago. The incorporation of the biological sciences is natural for our programs and has brought the expertise of our researchers to nanotechnology levels. It’s exciting to see the research and develop-ment of our professionals in industry and academia. There will be no‘leveling off’ of engineering in this field as population growth continues,demands for more nutritious foods grow, and resources to producefood, fiber, and energy become limited.”

Huggins – “I believe our role must continue to be the unique focus on how to best produce, store, and process agricultural/food products.This will utilize our unique engineering-based educational programshaving a biological emphasis to innovate applications that make a positive difference.”

Gustafson – “We are well positioned to practice engineering in a waythat creates sustainable and applied solutions to some of the mostchallenging problems of food, water, energy and environmental healthlocally and worldwide. We can collaborate across other disciplinesthat share our passion for seeing an abundance of food and water resources, in a world where energy is used in a sustainable mannerand the environment is protected or maybe even improved.”

Q. Any words of wisdom for today’s graduates?Bosworth – “Find a career that can benefit mankind, provide a great vocational opportunity for yourself, and have personal satisfaction.”

Huggins – “One’s attitude and how well one respects and works withother people will be the keys to ultimate personal success and impact.”

Gustafson – “The need to be professionally affiliated with an organization like ASABE is critical to continued professional success.It is both a resource and a means for making contributions well beyond what we can do as individuals.”

Summer 2017 I ABE@Illinois I 1716

Many ABE alumniand friends of thedepartment stay

connected to our departmentthrough participation in the Exter-nal Advisory Committee (EAC).Members bring their unique under-standings of our department, theirexperiences in the workplace, andtheir knowledge of the industry tothe table. Their contributions have

been significant and instrumentalin the growth of our program.

Chad Yagow, B.S. ’01 AgE, andKay Whitlock, B.S. ’70 AgE, arepast members of the committeewho began their six-year appoint-ments in 2007. Yagow continues toserve the department as the ABErepresentative to the ACES AlumniBoard. Here the two offer both reflections on the past and advicefor the future of the department.

Whitlock begins: “During mytenure, the Ag Mech major mor-phed into Technical Systems Management [TSM], and the department name was changedfrom Agricultural Engineering to Agricultural and Biological Engineering. Those changes weremore than just words. They are abetter fit for some of the chal-lenges in our society.”

Yagow says later changes madein TSM aided funding efforts forthe department. “Since we openedup our programming in TSM, trans-fer students from other depart-ments were able to take some ofthe core curriculum classes we offered. That helped generate theinstructional units we needed toget funding to allow growth in thedepartment. It also allowed stu-dents to see what else we had to

offer from the standpoints ofteaching and hands-on research.TSM has blossomed, and the department has doubled in size.”

With the name change to Agri-cultural and Biological Engineer-ing, Yagow says, there has been adefinite shift in the emphasis ofthe department. “We’ve donesome strategic hiring in the biolog-ical area, and there has been more

growth there than in the more tra-ditional disciplines like power ma-chinery and off-road equipment.

“The change has made the de-partment much more diverse thanwhen I was a student,” he says,“and that’s a good thing. I do thinkwe have to be careful to balancethe swing of the pendulum,though. We can’t neglect our re-cruitment of faculty and students

from the more traditional disci-plines. Those were our foundation,and we can’t forget about whatgot us to where we’re at.”

Overall, Yagow says, the mix ofbiological sciences and engineer-ing is a good change. “It’s one ofthe strengths of the department.We’re at the nexus of those differ-ent systems, and no one else oncampus can give you that combi-nation. As we continue to researchand promote how mechanical sys-tems and biological systems inter-act, we’ll become even stronger.”

Whitlock notes another impor-tant change—the makeup of thestudent body. “In the late ’60s andearly ’70s, except for me and twoor three support staff, there wereno women in the building. Ever. Inthose years, almost all our under-graduate students were white,Christian, Illinois family farm boys.”Today when she walks into the agengineering building, Whitlock

says, “I see diversity in everysense of the word. I know we’redelivering a well-educated and di-verse group to take on the chal-lenges of the future.”

Yagow agrees: “Agricultural andbiological engineers are going toplay a critical role in the challengeof feeding the world’s populationin the future. Understanding howag and bio engineering systemscan work together to meet thatchallenge is crucial.”

Yagow believes there are threethings the department can do toprepare students. “We need tofirst make sure graduates aregrounded in the basics. Knowl-edge of all the different disciplinesis very important,” he says.

“Second, they need a high levelof competency in emerging tech-nology. Ag and bio engineers areby nature systems thinkers, andunderstanding the new technol-ogy that lets those systems worktogether is essential.

“Finally, our grads need to beable to communicate the informa-tion they have learned to otherpeople. Understanding it is onething. Giving them strong commu-nication skills enabling them totransfer information, through writing or speaking, to people

who need it will be paramount in importance.”

In April, the current ExternalAdvisory Committee met to ad-dress needs and challenges facedby today’s department. Topics included the value of creating anon-thesis master’s in engineer-ing, finding a focus for the department’s diverse research, increasing engagement with ouralumni, and defining clear goals inour fundraising efforts.

The department looks ahead toa challenging and exciting future,and we would like to express our gratitude to all the men andwomen who have served on theEAC. Your commitment to our department is appreciated morethan we can say, and your contri-butions have made, and will continue to make, our programone of the best in the nation.

Giving back through the EAC

“It’s one of the strengths of the department. We’re at the nexus ofthose different systems, and no one else on campus can give you

that combination.”

“Agricultural and biological engineers are going to play acritical role in the challenge offeeding the world’s population

in the future.”

Current members of the External Advisory Committee include, left to right: Scott Dixon, M.S. ’06 AgE, Interim Head Alan Hansen, Mark Niemeyer, B.S. ’83 AgE, J.B. Priest, Ph.D. ’99 AgE, andChris Harbourt, Ph.D. ’02, AgE

“I see diversity in every sense of the word. I know we’re

delivering a well-educated anddiverse group to take on thechallenges of the future.”

EXTERNAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE

EXTERNAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE[Proposed mission statement]

• Help support the department in developing and achieving its mission and strategic objectives

• Improve the understanding of what graduates of the program will need upon graduation

• Transfer knowledge and insight about global and domestic trends and practices in business and the engineering industry

• Help identify and jointly develop potential solutions forconstraints, barriers, or critical issues that may inhibit ordelay the department from achieving its mission andstrategic objectives

• Improve the quality of the educational experience by interjecting practical experience into the overall program

Staci and Chad Yagow, B.S. ’01 AgE

Kay Whitlock, B.S. ’70 AgE

2

COLLEGE OF

ACESENGINEERINGAT ILLINOIS

Department of Agricultural & Biological Engineering338 Agricultural Engineering Sciences Building1304 W. Pennsylvania AvenueUrbana, IL 61801

NONPROFITORGANIZATION

U.S. POSTAGE PAIDCHAMPAIGN, ILPERMIT NO. 453

The Tractor Laboratory in the late 1920s

We want your feedback about ABE@Illinois. Please send your comments to Leanne Lucas at [email protected].

ABE.ILLINOIS.EDU