~ BRAQUE · 2018-12-19 · in the work of Braque over that of Pablo Picasso was unique, as was his...

Transcript of ~ BRAQUE · 2018-12-19 · in the work of Braque over that of Pablo Picasso was unique, as was his...

BRAQUE

1928 1945–

ALBERT EUGENE GALLATIN Georges Braque , 1931

PAUL STRAND Georges Braque, Varengeville-sur-Mer, France , 1957

CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

BRAQUE

1928 1945–

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, St. Louis

The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

Munich London New York

Karen K. Butler with Renée Maurer

Essays by

Karen K. Butler

Patricia Favero

Uwe Fleckner

Gordon Hughes

Narayan Khandekar

Renée Maurer

Erin Mysak

Reprinted essays by

Carl Einstein

Jean Paulhan

with an introduction by

Éric Trudel

GEORGES BRAQUE Glass and Fruit , 1931

Contents

8 Foreword

Sabine Eckmann, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Dorothy Kosinski, The Phillips Collection

9 Preface and Acknowledgments

Karen K. Butler, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Renée Maurer, The Phillips Collection

12 Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945:

The Known and Unknown Worlds

Karen K. Butler

30 Independent Minds:

Duncan Phillips and Georges Braque

Renée Maurer

52 The Joy of Hallucination:

On Carl Einstein and the Art of Georges Braque

Uwe Fleckner

74 Braque's Regard

Gordon Hughes

90 Material and Process in Georges Braque’s Still-Life Paintings, 1928—1944

Patricia Favero

Erin Mysak

Narayan Khandekar

113 Plates

197 Georges Braque (1933) by Carl Einstein

201 Braque le patron (1952) by Jean Paulhan

Translated with an introduction by Éric Trudel

219 Chronology

227 Artworks in the Exhibition

231 Index

238 Reproduction Credits

239 Lenders to the Exhibition

239 Contributors

Contents

8 Foreword

Sabine Eckmann, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Dorothy Kosinski, The Phillips Collection

9 Preface and Acknowledgments

Karen K. Butler, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Renée Maurer, The Phillips Collection

12 Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945:

The Known and Unknown Worlds

Karen K. Butler

30 Independent Minds:

Duncan Phillips and Georges Braque

Renée Maurer

52 The Joy of Hallucination:

On Carl Einstein and the Art of Georges Braque

Uwe Fleckner

74 Braque's Regard

Gordon Hughes

90 Material and Process in Georges Braque’s Still-Life Paintings, 1928—1944

Patricia Favero

Erin Mysak

Narayan Khandekar

113 Plates

197 Georges Braque (1933) by Carl Einstein

201 Braque le patron (1952) by Jean Paulhan

Translated with an introduction by Éric Trudel

219 Chronology

227 Artworks in the Exhibition

231 Index

238 Reproduction Credits

239 Lenders to the Exhibition

239 Contributors

8CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

Foreword

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945 marks the first

occasion for The Phillips Collection and the Mildred Lane Kemper

Art Museum to collaborate on a major international loan exhibition

and scholarly publication. This groundbreaking project provides

new insight into the creative process of Georges Braque and

examines the critical reception of his modernist work. While

attention has been devoted to Braque’s early and late canvases,

scholars and curators have overlooked the artist’s still lifes painted

midcareer, after World War I and through the end of World War II.

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945 is the first to

foreground this important moment and the first major museum

exhibition in the United States on Braque in twenty-five years.

The exhibition considers Braque’s paintings within the

context of the political and cultural upheaval during the years

leading up to and through World War II, a transitional time in the

artist’s own practice. Attending to the cyclical nature of the artist’s

work, the project examines the transformations in Braque’s creative

process, as he moved from painting small, intimate interiors in the

late 1920s, to depicting bold, large-scale, tactile Cubist spaces in

the 1930s, to creating personal renderings of daily life in the 1940s.

The exhibition and catalog also focus on his work in relation to

contemporary aesthetic debates and a politically engaged culture.

In order to understand Braque’s artistic process, conservators

performed technical analysis on specific paintings to investigate

how he manipulated art materials for compositional effect and

returned to canvases to alter and rework the paint surface. Braque’s

methods and techniques—his pigments and materials—during this

moment are all examined for the first time.

Duncan Phillips, founder of The Phillips Collection,

considered Braque to be one of the master painters of the twenti-

eth century, and his work has long been associated with the

museum’s modernist collection. Accordingly, the exhibition and

catalog also examine the pioneering role that Phillips played in

introducing Braque’s art to American audiences. Phillips’s interest

in the work of Braque over that of Pablo Picasso was unique, as

was his conviction that “the artistries of the reserved Frenchman”

would better stand the test of time. Phillips’s early support of

Braque began in 1927, before that of most other major modern art

museums in America. Between 1927 and 1953, Phillips acquired ten

canvases by Braque for the collection, underscoring the signifi-

cance he attributed to the artist as well as to French modernist

painting. Four of these acquisitions are featured in both venues of

the exhibition, including the impressive The Round Table (1929)

and The Washstand (1944). Phillips also hosted the first museum

retrospective of Braque’s art that toured across America; several

paintings from this 1939 exhibition are displayed together again

here, for the first time in nearly seventy-five years. Continuing the

legacy of Phillips, the museum presented in 1982 the first exhibition

devoted to the significance of Braque’s later years, Georges Braque:

The Late Paintings 1940–1963. The paintings in the current

exhibition, Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945, and

those that Phillips collected are a record of his vision of what

mattered most to him in modern art.

In the collection of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum,

the acquisitions of two paintings by Braque from the 1930s are

linked to significant moments in history. In 1941, German exile H. W.

Janson joined the faculty of Washington University’s Department of

Art History & Archaeology and initiated an expansive program to

revitalize the University’s museum. His mission to build the “finest

collection of contemporary art assembled on any American

campus” led to the deaccession of over six hundred objects and the

acquisition of Still Life with Glass (1930) along with approximately

forty works predominantly from European modernist movements.

Acquired from Braque’s dealer in 1946, the painting was one of the

works that Paul Rosenberg was able to bring with him to the United

States when he fled the German occupation of Paris in 1940.

Janson’s emphasis on artworks guided by primarily Cubist and

Constructivist approaches had a lasting impact on the development

of the University’s collection. His successors and others, such as

donors Florence and Richard K. Weil, extended the collection

through the addition of noteworthy examples of European modern-

ism, including Still Life with Oysters (1937). These two paintings by

Braque, one looking back to his Cubist experiments with Picasso

and the other a more naturalistic but nonetheless experimental

investigation of abstracted spaces, reveal an ambitious artist

negotiating his place in the changing field of his practice.

A project of this scope and complexity would not be

possible without the participation of numerous lenders, and we

thank them for entrusting us with their artworks on behalf of

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945. Their

willingness to lend paintings and their profound commitment to the

exhibition testify to the contributions to the scholarship on Georges

Braque made by the curators of this exhibition. Curatorial expertise

from both institutions shaped both the exhibition and its catalog.

The project was directed by assistant curator Karen K. Butler at the

Kemper Art Museum and assistant curator Renée Maurer at The

Phillips Collection. We are very grateful for their commitment and

devotion to the project.

We are also immensely grateful for the generous

financial support, received from many sources, that allowed us to

realize our aspirations for this project. The Federal Council on the

Arts and the Humanities generously indemnified this exhibition;

we thank them for their support. We also thank David Nash

of Mitchell-Innes & Nash for his expertise. At the Mildred Lane

Kemper Art Museum, we are especially grateful for the support

of the Kemper family (James M. Kemper, Jr., the David Woods

9PREFACEFOREWORD

Kemper Memorial Foundation, and the William T. Kemper Founda-

tion) and John and Anabeth Weil, as well as lead support from the

Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne and the National Endowment for

the Arts. At The Phillips Collection, we are thankful to the

National Endowment for the Arts for supporting the exhibition’s

presentation in Washington, DC.

As institutions, we are fortunate to share this innovative

show, which brings together works of exceptional quality from

collections in the United States and Europe.

Sabine Eckmann, PhD

William T. Kemper Director and Chief Curator

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Dorothy Kosinski, PhD

Director

The Phillips Collection

Preface and Acknowledgments

One of the leading founders of Cubism, Georges Braque employed

the genre of the still life to conduct a lifelong investigation into the

nature of perception. In an interview late in his career, he explained

that his goal as an artist had long been to render the space between

humans and the objects that make up everyday life. Braque

differentiated between his attempts to represent the ephemeral

quality of lived experience from more conventional representations

of described objects in relation to one another. “Tactile space,” he

said, “separates us from objects, as opposed to visual space, which

separates objects from one another. I have spent my life trying to

paint the former kind.”1 It was the still life, with its focus on objects

within reach of the hand, that best allowed him to address this

relationship.

In many ways, an investigation of this notion of “tactile

space” has been a guiding paradigm of Georges Braque and the

Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945. It is our premise that Braque’s interest

in rendering the perceptual quality of lived experience is intimately

related to his artistic process as well as to his long-standing

attention to the materiality of objects. Braque systematically

worked through groups of related paintings, revising them for years

on end, or returning later to take up what he had put aside. This

resulted in cycles of works, some ranging across an entire decade,

that explore with variation the same motif, utilizing experimental

techniques and materials to evoke the intangible but no less real

relation between us and things. Many of these cycles are gathered

here, some exhibited together for the first time since the 1930s,

in order to explore the connection between artistic process and

visual experience.

Braque’s formalist attention to the medium of painting

and the genre of the still life during the turbulent period leading up

to and throughout World War II is interesting in light of questions

dominating the aesthetic debates of the time about the autonomy

of the artwork and its relationship to political events. With the onset

of World War II in the late 1930s—the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the

Munich Accords in 1938, and the eventual declaration of war by

Britain and France in response to Germany’s invasion of Poland in

1939—artistic production, and culture more broadly, was more and

more held accountable for its place in the world. For some critics

Braque’s elaborately constructed interiors and still lifes appeared to

be at odds with historical events; for others, the spatial and material

ambiguity of his works and their lack of connection to the external

world provided a realm free from ideology; and for some, Braque’s

extended focus on the still object was a reflection, if in reverse, of

the violent times.

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945

moves chronologically, examining paintings produced from 1928—

roughly when Braque’s work emerged from the neoclassicism of the

retour à l’ordre (return to order)—to 1945, with the end of World

War II. By focusing on less than two decades of the artist’s work

and on the genre of the still life (though Braque did produce

landscapes and figures during this period), the exhibition offers an

unprecedented investigation of the cyclic nature of Braque’s

process and materials, while examining the interplay of the external

and internal worlds of history and art.

It is our hope that this publication and the exhibition will

further open the aesthetic debates surrounding Braque’s work in

relation to a time of dramatic social and political change and inspire

additional scholarship on the relationship between art and politics,

between artistic process and the finished work, and between an

artist and his critics. The five essays in this volume all investigate

Braque’s devotion to the still life within this context, albeit from

different perspectives, ultimately conveying a complex portrait of

an artist at a time in which culture was increasingly subjected to

political claims.

Karen K. Butler’s essay explores the French reception of

Braque’s work before and during World War II. She argues that

while critics, and even Braque himself, tended to highlight the

autonomous nature of his Cubist pictorial worlds, it is in the works’

insistent lack of political engagement that one can locate the

historical specificity of his still-life paintings. They refer to external

events only indirectly and obliquely, creating a parallel interior

universe that is reliant on a bodily experience of space and that by

its very ambiguity resists politicized as well as apolitical readings.

10CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

Uwe Fleckner examines the development of Braque’s

career in the 1920s and early 1930s through his seminal relationship

with one of the leading early commentators on his work, the

German Jewish writer, cultural critic, and art historian Carl Einstein,

who organized Braque’s first major retrospective at the Kunsthalle

Basel in Switzerland in 1933 and published the first monograph on

the artist in 1934. Fleckner argues that Einstein saw in Braque’s art

a form of “subjective realism,” a radically new type of mental

cognition that replaced the conventions of mimetic description with

experiential representations of the viewer’s perception of space. In

this reading, Braque’s paintings of the time were a leading example

of a new form of aesthetic intervention. Gordon Hughes also draws

upon the response of Braque’s immediate contemporaries—the

critic Jean Paulhan and the poet Francis Ponge—in his essay and

uses their experiential prose as guides to his own embodied reading

of Braque’s still lifes. Hughes’s essay, in itself an evocative re-

creation of the effect of Braque’s still lifes on the viewer, closely

looks at the formats and motifs of Braque’s still lifes from the 1930s

and 1940s, arguing that their intertwined frontal and horizontal

orientations and the tension between depicted and literal forms

enacts the painter’s and, by extension, the viewer’s sense of being

in the world.

Renée Maurer discusses the reception of Braque’s art in

the United States during the late 1920s and 1930s. Maurer’s focus is

on one of the artist’s important early American patrons, Duncan

Phillips, his support of Braque’s work through major acquisitions,

installations, and exhibitions at The Phillips Collection, and the

ways in which his evolving tastes as a collector, museum founder,

and director helped to transform how Braque’s work was received

in the United States.

Conservator Patricia Favero and conservation scientists

Erin Mysak and Narayan Khandekar examined works by Braque

from this period and present the results of their close investigation

of the methods and processes Braque employed in his still lifes

during this transitional time. The findings of their material analysis

support, both directly and indirectly, the conceptual theorizations

of Braque’s work by critics of his own time, such as Einstein and

Paulhan; by the decades of scholarship since then; and by the

authors of this volume.

It is also the goal of this publication to give voice to

Braque’s early commentators and to make their writings, many of

which were published only in French or German and often in

hard-to-find editions or catalogs, accessible for current and future

scholars. Thus, we present the first complete English translation of

Einstein’s introduction to the catalog of Braque’s 1933 retrospective

and of Paulhan’s essay Braque le patron, first published in 1945 and

completed in 1952.

* * *

From its very beginning, this project benefited from the assistance

of a number of individuals. Both the catalog and the exhibition were

the topics of numerous conversations with friends and colleagues,

whose good will and intellectual support were crucial to the

project’s success. We are particularly indebted to Stephanie

D’Alessandro, Claire Barry, Sophie Bowness, Elizabeth Childs, David

Cottington, Lionel Cuillé, Bart J. C. Devolder, Sabine Eckmann,

Susan Behrends Frank, Paul Galvez, John Golding, Mark Haxthau-

sen, Megan Heuer, John Klein, Eik Kahng, Allison Langley, Meredith

Malone, Klaus Ottmann, Charles Palermo, Eliza Rathbone, Alexandra

Schwartz, and Laurie Stein.

The support of many individuals affiliated with museums,

private collections, and galleries around the world also contributed

significantly to the successful realization of this project. For their

generous assistance, we are particularly grateful to Marion Acker-

mann, William Acquavella, Paloma Alarcó, Hope Alswang, Peter

Barberie, Stephanie Barron, Carlos Basualdo, Laura Bechter, Neal

Benezra, Brent R. Benjamin, Maria Brassel, Cheryl Brutvan, Thomas P.

Campbell, Catherine Chagneau, William J. Chiego, Harry Cooper,

Electra Ducommun DePeyster, Andria Derstine, Stephan Diederich,

Robert Ducommun, Jean Edmonson, Michael Findlay, Ilda François,

David Franklin, Adelheid M. Gealt, Michael Govan, Judy Greenberg,

Robert Grosman, Brent R. Harris, Jeffrey Harrison, Josef Helfenstein,

William Hennessey, Joshua Holdeman, Simon Kelly, Brian P. Kennedy,

Sharon Kim, Kasper König, Annette Kruszynski, Heather Lammers,

Brooke Lampley, Quentin Laurens, Brigitte Leal, Ellen W. Lee, Galen

Lee, Olga Makhroff, Andrea Mall, Jenny McComas, Mitchell Merling,

Jacqueline Munck, David Nash, Alexander L. Nyerges, Alfred

Pacquement, Earl A. Powell III, Donald Prochera, Emily Rauh Pulitzer,

Rebecca Rabinow, Marc Rich, William Robinson, Mrs. Alexandre P.

Rosenberg, Timothy Rub, Guillermo Solana, Michael Taylor, Anna

Vallye, Charles Venable, Michelle White, Stephanie Wiles, and John

Zarobell, and to additional private collectors in Paris, Philadelphia,

New York, Washington, DC, and throughout Switzerland. We are

profoundly indebted to all the individuals and institutions who have

agreed to share their works on behalf of the exhibition. A complete

list of lenders can be found on page 239.

We would like to thank the conservators at the Chrysler

Museum of Art, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Indiana University

Art Museum, Indianapolis Museum of Art, The Menil Collection,

Museum Ludwig, Cologne, National Gallery of Art, Philadelphia

Museum of Art, Saint Louis Art Museum, and San Francisco Museum

of Modern Art, who graciously made their works available to us for

scholarly examination. We also thank the research staff at the

Archives of American Art, The Arts Club of Chicago, The Frick

Collection, Kunsthalle Basel, The Morgan Library & Museum, The

Newberry, The Paul Rosenberg Archives, and San Francisco

Museum of Modern Art Library and Archives.

11ACKNOWLEDGMENTSPREFACE

An outstanding group of scholars contributed insightful

essays to the catalog, and we are grateful to Uwe Fleckner and

Gordon Hughes, as well as to the conservation teamwork of Patricia

Favero, Erin Mysak, and Narayan Khandekar, all of whom also

provided helpful and friendly counsel and dialogue. Éric Trudel’s

introduction to and translation of Jean Paulhan’s Braque le patron is

an essential contribution, and we are also grateful to Kevin Cook for

his thoughtful translation of Uwe Fleckner’s essay and, along with

Fleckner, of Carl Einstein’s essay. We are also grateful to Jacqueline

Paulhan, Claire Paulhan, Bernard Baillaud, and Editions Gallimard for

permission to publish and translate Paulhan’s important essay.

This beautiful scholarly catalog would not have been

possible without the editorial acumen and unflagging devotion of

Jane E. Neidhardt, managing editor of publications at the Mildred

Lane Kemper Art Museum, for which we are boundlessly grateful.

Consulting colleague Karen Jacobson contributed invaluable editorial

input, and Eileen G’Sell and Holly Tasker, publications assistants,

worked tirelessly gathering images and permissions for reproduction;

they provided important editorial assistance, as did Esther Ferington.

Michael Worthington at Counterspace designed the catalog with

intelligence, insight, and creativity befitting the project. Mary

of the book. Aliya Reich compiled the chronology, and Kathleen

Preciado prepared the index for the publication.

Numerous staff members at both museums contributed

generously to the organization of this project. At the Mildred Lane

Kemper Art Museum, these include Rachel Keith, chief registrar,

whose expertise and professionalism were essential to securing the

loans and who oversaw all aspects of the exhibition’s installation in

St. Louis. Additional thanks are due to Kim Broker and Kristin Good,

assistant registrars; Jan Hessel, facilities manager; Ron Weaver,

exhibition preparator; Allison Taylor, manager of education

programs; and Mike Venso, manager of marketing, visitor services,

and events. Michael Adrio, director of development at the Sam Fox

School of Design & Visual Arts, and Elizabeth Embree, senior

associate director of foundation relations, provided essential support

for funding and grant development. We are grateful for the research

assistance of David Leonard, Benjamin Murphy, Carolina Peguero,

and Rebecca Wahrman. Leah Chizek provided essential translations

of German documents. Frank Escher and Ravi GuneWardena’s

beautiful design of the exhibition in St. Louis was an essential

contribution. And we continue to be deeply grateful to Carmon

Colangelo, dean of the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, and

Mark Wrighton, chancellor of Washington University, for their

unfailing commitment to this and all Kemper Art Museum projects.

At The Phillips Collection, the project received the

invaluable guidance and assistance of numerous individuals,

including Joseph Holbach, chief registrar and director of special

initiatives; Trish Waters, associate registrar for exhibitions, who

along with Rachel Keith at the Kemper Art Museum diligently

coordinated crating and shipping arrangements and managed the

indemnity application; Sue Nichols, chief operating officer, who

tirelessly negotiated and administered contracts; Cherie Nichols,

director of budgeting and reporting, who oversaw all project costs;

Gretchen Martin, assistant registrar, who performed key visual

resource requests; and librarians Karen Schneider and Sarah

Osborne-Bender, who aided with numerous research queries.

Additional thanks go to essential museum staff, including Ann

Greer, director of communications and marketing; Cecilia Wagner,

publicity and marketing manager; Vivian Djen, marketing communi-

cations editor; Suzanne Wright, director of education; Brooke

Rosenblatt, education specialist for public programs and interpreta-

tion; Margaret Collerd, public programs and in-gallery coordinator;

Dale Mott, director of development; Christine Hollins, director of

institutional giving; Bridget McNamara, grants writer; Liza Stelka,

curatorial coordinator; and Dan Datlow, director of facilities and

security. We also acknowledge the dedication and efforts of the

installation team of Bill Koberg, Shelly Wischhusen, Alec MacKaye,

and designer Val Lewton.

For their support of this project from the beginning and for

their unfailing institutional commitment to its success, we are deeply

grateful to our respective directors: Sabine Eckmann, William T.

Kemper Director and Chief Curator of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art

Museum; and Dorothy Kosinski, director of The Phillips Collection.

This ambitious project could not have been accomplished

without the essential financial support of many. We extend our

sincere thanks to James M. Kemper, Jr.; the David Woods Kemper

Memorial Foundation; the William T. Kemper Foundation; John and

Anabeth Weil; Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne; the National

Endowment for the Arts; the Hortense Lewin Art Fund; the Missouri

Arts Council, a state agency; the Regional Arts Commission; and

members of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum; as well as to the

Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities, which supported

the exhibition with an indemnity.

Karen K. Butler

Assistant Curator

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Renée Maurer

Assistant Curator

The Phillips Collection

NOTES

1. Braque to John Richardson, in “Braque Discusses His Art,”

Réalités, no. 93 (August 1958): 28.

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945: The Known and Unknown Worlds

UNKNOWNWORLDSAND

THEKNOWN 13

Notes1. Georges Braque, in Jacques Lassaigne, “Un entretien avec Georges Braque” (1961), XXe Siècle, no. 41 (December 1973): 6. All translations are mine unless otherwise noted.2. Georges Braque, in John Richardson, “Braque Discusses His Art,” Réalités, no. 93 (August 1958): 28.3. Georges Braque, “Enquête,” Cahiers d’art, no. 1–4 (1939): 66, as trans-lated in Alex Danchev, “The Strategy of Still Life; or, The Politics of Georges Braque,” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 31 (January–March 2006): 3.

GEORGES BRAQUE’S ABIDING INTEREST IN STILL LIFE is well known. From the height of

his early Cubist investigations—roughly from 1907 to 1914—until his death in 1963, still

life was the primary subject of Braque’s art. He believed that the genre allowed the

artist to explore one of the questions that has been central to Western art since the

Renaissance: the relationship between the representation of space and the experience

of the lived body in space. As the artist repeatedly said, it was still life, with its long

history of depicting the materiality of things, that seemed most able to invoke the

sensations he was searching for: “I worked from nature. It was this that directed me to

still life. I found there a more objective element than landscape. The discovery of the

tactile space that put my arm in motion in front of landscape invited me to look for an

even closer, more tangible contact. If a still life is no longer within reach of the hand, it

ceases to be a still life and to move me.” 1 The question of how to depict the tactile

quality of an object and what he described as the space that “separates us from

objects” 2 was one that Braque found compelling throughout his life.

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945 takes as its field of

exploration the artist’s still lifes made during the tumultuous years leading up to and

during World War II. These were years in which questions about the relationship

between aesthetics and politics came to the fore in particularly provocative ways.

With the rise of fascism in the 1930s and the increasing inevitability of war, cultural

production became fraught with issues of responsibility and commitment. In a war-torn

era that also saw the emergence of philosophies that questioned the very nature of

human existence and experience, such as existentialism and phenomenology, Braque

appears to have continued his exploration of the space of the Cubist still life with

the same formalist, self-reflective attention to the medium that began as far back as

the 1910s. On the eve of the war he was asked about the relationship of his work to

historical events, and he acknowledged his belief in the separateness of art from

the political sphere. An artist, he said, suffered with the weight of historical events

just as much as anyone, but art was nonetheless something else: “Fulfillment requires

physical time; if it takes ten years to conceive and execute a canvas, how is the

painter supposed to stay abreast of events? A painting is not a snapshot. Once again,

this does not mean that the painter is not influenced, concerned, and more by history;

he can suffer without being militant. Only let us distinguish, categorically, between art

and current affairs.” 3

Braque’s statements about art indicate that his work was grounded in a belief

in aesthetic autonomy, in the notion that art is independent from society and the

sociopolitical events that produce it while at the same time being deeply implicated in

a perceptual experience of the world and the objects in it. And yet, even if at first

glance they appear so, his paintings are not as separate from the events of the outside

world as Braque would have them, for it is precisely their turning inward, to unknown

FIG. 1

Georges Braque

Studio with Black Vase, 1938Plate 27

14CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

insist on the differences between Picasso and Braque in 1911 and 1912; and even right when they say that what we are con-fronted with at this point in Cubism (in contrast to others) is a hierarchy as opposed to collectivity. A dyad with Picasso on top.” See Clark, “Cubism and Collectivity,” 223. 8. For a long time the early Cubist years remained the focal point for scholarship, though recently there has been an expansion in curatorial and scholarly interest in the scope of Cubism, reflected in an extension of the timeline and in a broadening of focus to include the artists and movements that were affiliated with the move-ment as it spread beyond Braque’s and Picasso’s studios. Recent examples of this include T. J. Clark’s Mellon Lectures on Picasso’s work from the 1920s and 1930s at the National Gallery of Art; Yve-Alain Bois’s exhibi-tion Picasso, 1917–1937 at the Complesso del Vittoriano in Rome in 2008–9 and its accompanying catalog; Carol Eliel’s exhibition L’Esprit Nouveau: Purism in Paris, 1918–1925 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2001–2 and its accompanying catalog; and Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, eds., A Cubism Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), which broadens the understanding of the contemporary reception of French Cubism by in-cluding German, English, Czech, Italian, and Spanish primary sources.

4. See Jean Paulhan, “Braque ou le sens du caché,” Cahiers d’art, numéro unique (1940–44): 87–88.5. The scholarship on the early years of Cubism is extensive and multigener-ational, and while this list is by no means exhaustive, it includes the founda-tional English-language scholarship of Yve-Alain Bois, Pepe Carmel, T. J. Clark, Douglas Cooper, David Cottington, John Golding, Christopher Green, Rosalind Krauss, Christine Poggi, John Richardson, William Rubin, Leo Steinberg, and Jeffrey Wolf, as well as many others who have made more recent signifi-cant contributions. 6. T. J. Clark, “Cubism and Collectivity,” in Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 223.7. William Rubin’s semi-nal exhibition Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism, presented at the Museum of Modern Art in 1989, and the accompanying symposium, published as Lynn Zelevansky, ed., Picasso and Braque: A Symposium (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1992), established this hierarchy for much of recent scholarship. Even T. J. Clark, whose essay sets out to explore the collective nature of the project—the two artists’ desire to create a shared language that moved beyond the modernist paradigm of individual-ity—concludes with the observation that Picasso was the better artist: “I am afraid that the critics are ultimately right to

worlds of imagined experiences, that makes them relevant to questions of aesthetics

and politics for his contemporaries. In his still lifes from this period, Braque altered and

obscured the sanctified terrain of the bourgeois interior through standard Cubist

devices such as overlapping planes and the separation of color from contour line.

In this, as well as in the introduction of a kind of figurative equivocation that he

compared to poetic metaphor and that makes the identification of everyday objects

difficult, Braque created complex spatial and symbolic systems that require careful

visual navigation and analysis. Although the viewer is invited into these worlds, to

imagine entering these spaces and touching these objects, the experience is often

troubled and incomplete. It is this very ambiguity—as if the paintings had something

to hide, as one critic put it 4—that makes them defy easy categorization and opens

them up to questions of political engagement. There is a tension between Braque’s

devotion to the creation of a world that is purely internal—both literally, with respect

to subject matter (the bourgeois interior and its attendant objects), and experientially,

with its imaginary scenes requiring perceptual exploration—and the historical

complexities of the world beyond.

Most scholarship on Cubism has focused on the late 1900s and early 1910s,

when the famous collaboration between Braque and Pablo Picasso that gave rise to

the movement was at its height.5 These were the years when the two artists over-

turned the history of Western representation, achieving, as T. J. Clark has argued,

nothing short of “a way of painting as if they had happened on a whole new represen-

tational idiom—a new understanding of the world.” 6 Although much of the scholarship

acknowledges the collaborative nature of the project—hence Braque’s famous dictum

that he and Picasso were like two mountain climbers roped together—it generally

establishes Picasso as the innovator and leader in the exchange.7 While it is not the

goal of this project to take issue with this claim, it is the case that, at least in part due

to this critical assessment, there are lacunae in the scholarship on Braque’s work.8

Periods of his post-Cubist work have been explored by scholars, including the retour

à l’ordre (return to order) years of the late 1910s and early 1920s and his great late

cycles of billiard tables, studios, and birds.9 Braque’s still lifes from 1928 to 1945—an

interim period of renewed experimentation between the return to order and the end of

World War II—and their relation to the complexities of the sociopolitical developments

of the time have, however, not been examined in any sustained way. It is the objective

of this exhibition and the accompanying publication to offer a variety of focused

perspectives on Braque’s art of this turbulent era.

UNKNOWNWORLDSAND

THEKNOWN 15

9. Kenneth Silver and Christopher Green situate Braque’s work between 1917 and the mid-1920s as part of the return to order, a general rejection of the aesthetic innovation and progress of the prewar years and a return to an art of Neoclassicism and thematic wholeness. See Kenneth E. Silver, Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-garde and the First World War, 1914–1925 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989); Christopher Green, Cubism and Its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987); and more recently, the exhibition catalog Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918–1936 (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2010). For a recent examination of the late cycles created be-tween 1940 and Braque’s death in 1963, see John Golding, Sophie Bowness, and Isabelle Monod-Fontaine, Braque: The Late Works (New Haven, CT:

The Eve of the War In April 1939, on the eve of World War II, the Parisian art dealer Paul Rosenberg held an

exhibition of Braque’s recent work that exemplified the contradictions of the work at

that time, sparking complex responses by contemporary critics. The paintings in the

show—vibrantly colored, texturally varied still lifes, many set in lavishly decorated and

spatially ambiguous interiors—might be seen as the culmination of Braque’s increas-

ingly decorative and dramatically large-scale still lifes of the previous decade. For

many of the attendees, the works on view appeared to offer a refuge from troubling

historical events. Works containing two of the most symbolically significant motifs

of the 1930s, the vanitas and the artist’s studio, were on display in the exhibition, and

yet these paintings ripe with meaning and spatial complexity are difficult to interpret

as references to outside events.

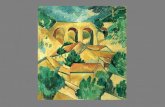

Studio with Black Vase (1938; fig. 1), which combines both the skull and the

studio and even includes a reference to the artist (in the slice of a dark silhouette

just to the right of the palette), epitomizes the clash between internal and external

worlds.10 A reflection on the act of creating, it consists of a painting of an artist

painting within an interior, on the wall of which hangs a still-life painting. The artist’s

studio has a long history within Western art, and the motif places the work in

dialogue not only with representations from earlier eras but also with works by

Braque’s contemporaries, such as Henri Matisse and Picasso, both of whom had

painted a number of significant depictions of the artist’s studio. This too is primarily

an internal dialogue: one of Braque inserting himself into the great tradition of

artistic self-reflection. Yet the work is not entirely self-contained. Although it may

not be obvious at first, the painting is structured so that it interpolates the viewer,

enclosing him or her in the private world of the artist. Superimposed on the interior

world of Studio with Black Vase is a transparent geometric grid that resembles the

outer frame of an easel. Looking through it, the viewer takes on the role of the artist

looking through an easel at a depiction of an artist in his studio painting a still life.

As such the space beyond the canvas—the space between the painting and the real

easel, which the viewer can only imagine—is compressed onto the two-dimensional

space of the canvas itself. Within the work, the complicated series of discontinuous

and overlapping transparent planes and variously textured surfaces—wood grain,

marble, wallpaper, cloth—only further invites us into and enfolds us in this space.

The windowless room offers no escape, however, leaving us caught somewhere

between the real space in which we are standing and the world of the painting. The

work is most certainly an allegory of the act of painting, but how are we to under-

stand this allegory, in which we are invited to participate—as a formalist celebration

of the decorative excess and virtuosity of a master painter or as something more?

Yale University Press, 1997). The exhibition was organized by The Menil Collection, Houston, in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Arts, London. See also the still relevant essay by John Richardson on Braque’s studio series, “The Ateliers of Braque,” Burlington Magazine 97 (June 1955): 164–71.10. For lists of works by Braque included in Rosenberg’s exhibitions throughout the 1930s, see Nicole S. Mangin, ed., Catalogue de l’oeuvre peint de Georges Braque: Peintures 1928–1935 (Paris: Maeght, 1962), and Mangin, ed., Catalogue de l’oeuvre peint de Georges Braque: Peintures 1936–1941 (Paris: Maeght, 1961); the 1939 exhibition, however, is not included. Given the matching di-mensions, it is likely that Studio with Black Vase is the work listed as Intérieur au vase noir in the catalog of Paul Rosenberg’s 1939 exhibition. See Exposition Braque: Oeuvres récentes (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), no. 1.

16CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

Moderne in August 1942, he was indeed mainly absent from public life in France during the war. He was, however, fairly active in the United States, thanks to the support of Rosenberg. For more on his participation in US exhibitions, see Renée Maurer’s essay in this volume, “Independent Minds: Duncan Phillips and Georges Braque.” 12. For another discussion of this aspect of Braque’s work at this time, see Gordon Hughes’s essay in this volume, “Braque’s Regard.”13. Stool, Vase, Palette is most likely Vase gris et pal-ette, no. 5 on the checklist of the 1939 exhibition.

11. Many reviewers of the 1943 Salon saw Braque’s participation as a kind of coming-out after a long silence. See, for example, Lucien Rebatet, “A propos du Salon d’automne: Révolutionnaires d’ar-rière-garde,” Je suis partout, October 29, 1943. Braque had been quite successful throughout the 1930s, holding solo shows almost yearly and participating in numerous group shows at Paul Rosenberg’s Paris and London galleries. (Rosenberg co-owned the London gallery known as Rosenberg & Helft with his brother-in-law Jacques Helft.) Although Braque was included in the Inauguration provisoire du Musée National d’Art

What are we to make of the fact that once we get our bearings in this space there is

a depiction of a shadowy figure holding a palette that resembles a skull as well as an

actual skull and cross seen from behind? Is this vanitas—a motif that is generally a

reference to the vanity of man and his interest in worldly pleasures in the face of the

inevitability and permanence of death—also an oblique reference to the tragedy of

war? Let us for the moment hold on to this question.

The exhibition at Rosenberg’s gallery would be the last exhibition in Paris of

Braque’s recent work for more than four years, until he was given a special room at the

Salon d’automne in 1943. His hiatus from public life in France may simply have been

a result of wartime circumstances (his Jewish dealer was forced to flee to the United

States), but it may also have been symptomatic of the larger questions plaguing his

work at the time.11 Indeed, although Braque had always painted still lifes set in bour-

geois interiors, during the late 1930s and early 1940s his still lifes became even more

oriented toward inner worlds, both in their devotion to the physical elements of the

interiors—increasingly the world that he painted was limited to scenes set within two

rooms of his own apartment—and in their incorporation of the viewer’s body and the

viewer’s space into their very structure.12

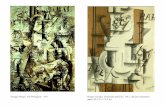

But let us return to the exhibition at Galerie Paul Rosenberg for a moment to

set the stage for the discussion of aesthetic debates to come (fig. 2). The 1939 show

was devoted mainly to the still life, a genre that is in itself generally limited to the

interior, if not the domestic, world. The works in the exhibition would have been

ravishing, though on the level of technique somewhat hermetic, consisting primarily

of Braque’s serial explorations of a limited range of objects: the same tables, vases,

tablecloths, skulls, palettes, paintbrushes, easels, and paintings on easels, painted in

different combinations, colors, and from slightly varied perspectives. The sparse,

descriptive titles of the works suggest that these are purely formalist investigations

of the still life and the interiors that contain them: Interior with Black Vase, Vase and

Table, The Baluster, Palette and Gray Vase, Vase in Front of a Window, Vase and

Palette, The Green Vase, Interior with Mauve Vase, and so on. Intentionally or

otherwise, these titles do not hint at either the symbolic density of the objects or the

remarkable textural and spatial complexity of the works.

Stool, Vase, Palette (1939; figs. 2, 3), is an example of the type of material and

spatial play that Braque was devoted to at the time: thick and thin, transparent and

opaque, dark and light, bursting forth yet spiraling in.13 In its attention to the details

of what is essentially the artist’s studio, it seems entirely guided by aesthetic notions

of form and technique. And yet with its obsessive rendering of the very real textures

and surfaces of things—of tablecloth, wood grain, and straw—it is oddly attentive to

the material dimensions of the real world. In both aspects, however, this is an internal

experience, one that necessitates the viewer turning inward, relying on his or her

UNKNOWNWORLDSAND

THEKNOWN 17

FIG. 2 (TOP)

Installation view of the exhibition of Georges Braque’s

paintings at Galerie Paul Rosenberg in Paris in 1939, show-

ing (left to right) Vanitas I (1938), Vase, Palette, and Skull

(1939), and The Blue Tablecloth (1938).

(BOTTOM)

Installation view of the exhibition of Georges Braque’s

paintings at Galerie Paul Rosenberg in Paris in 1939, show-

ing (left to right) Boat with Flag (1939), Baluster and Skull

(1938; plate 24), and Stool, Vase, Palette (1939; plate 28).

18CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

14. Germain Bazin, “Braque 1939,” Prométhée, no. 5 (June 1939): 180.15. For a detailed discussion of Braque’s movements at this time, see Danchev, “Strategy of Still Life,” 5–9.

imaginative abilities to comprehend the spatial discontinuity and textural variation of

Braque’s painted world. In Stool, Vase, Palette, the external and inner worlds become

conflated, and the viewer is invited to reimagine the experience of the artist himself

in painting this world.

At least one critic saw this apparent remove from the external world and

celebrated it. Germaine Bazin, at the time the curator of paintings at the Musée du

Louvre and a supporter of Braque’s, said of the exhibition at Rosenberg’s: “Standing

in the middle of these canvases, a few meters from the roaring and deafening noise of

the street, what a delicious impression of distance, of time stopped, of abstraction.

Just like that, one feels liberated from the real, released from the burden of this

insistent presence of the exterior world that modern life imposes on us. One enters

an unknown world.” 14 Like Braque’s paintings, Bazin’s comment was obscure. Although

it refers to the external world, Bazin’s review, which came out in June, barely acknowl-

edges the circumstances looming on the horizon: by this time the growing threat of

German imperial power was pronounced in France, and a few months later, in

September 1939, war was officially declared.

By all accounts, Braque was profoundly affected by the coming war. In August

1939 he and his wife, Marcelle, considered relocating to Geneva, though in the end

they decided to stay in France.15 When France and Britain declared war on Germany in

September 1939, Braque was at his country home in Varengeville, in Normandy. As the

Germans got closer to Paris, breaking the Maginot Line in May 1940, he and Marcelle

fled south to the Limousin region, where they took refuge with the family of his studio

assistant, Mariette Lachaud, and then with the painter André Derain and his wife in the

FIG. 3

Georges BraqueStool, Vase, Palette, 1939Plate 28

UNKNOWNWORLDSAND

THEKNOWN 19

Life,” 23n22). A review of Braque’s catalog raisonée confirms Danchev’s obser-vation. In 1938 and 1939 he made twenty-eight paintings each, but in 1940 he made only eight paintings; see Mangin, Peintures 1936–1941.19. This period in Braque’s career is the subject of Danchev, “Strategy of Still Life,” 1–26, one of the few detailed and complex ex-plorations of Braque’s life and work during World War II. Danchev argues that Braque exhibited a form of “active passivity,” a reference to French philosopher Jean Grenier’s notion of principled nonengagement with the occupier. Danchev’s essay is adapted from his biog-raphy of Braque, Georges Braque: A Life (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2005). Danchev’s article and biography have offered invaluable insights into Braque’s work and its reception at this moment. I am also grateful to Jennifer Pap, who shared her unpublished paper “Georges Braque and Occupation: German Taste and French Resistance,” in which she explores the critical response to Braque’s work during the war and the question of its relationship to history.

16. Mariette Lachaud, cited ibid., 6.17. For a detailed discussion of the relationship between Braque and Einstein, see Uwe Fleckner’s essay in this volume, “The Joy of Hallucination: On Carl Einstein and the Art of Georges Braque.” Rosenberg’s plight would also have resonated with events during World War I, for Braque’s German dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, given enemy alien status, was forced to close his gallery after his stock was confiscated by the French government, and Braque had to seek new representation. For a brief discussion of Rosenberg’s flight to New York, see Michael C. Fitzgerald, Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995), 262–68.18. Danchev cites a letter from Braque to Rosenberg, dated October 6, 1939, in which Braque describes his difficulties painting (see Danchev, “Strategy of Still Life,” 5, 23n21), and letters to Rosenberg dated April 13 and May 4, 1940, which indicate that Braque had returned to painting (see Danchev, “Strategy of Still

town of Gaujac, near Toulouse and the border with Spain, eventually returning in July

to Paris, where they remained for the duration of the war. The events leading up to

World War II would have had particular resonance for Braque, who had been severely

injured in World War I. Wounded in May 1915, he underwent trepanation and was

temporarily blind. He would not paint again until 1917. Lachaud later described the

artist’s feelings as war again threatened France: “He was so shocked by the disaster

that was looming. . . . His sensitive soul couldn’t bear what he had already lived

through personally during the First World War. It’s that above all that traumatized

him for more than a year.” 16 His fear for his own circumstances would only have been

compounded by the tragic events that affected others close to him. In early summer

of 1940 his Jewish dealer, Paul Rosenberg, was forced to flee to New York, and most

of his twentieth-century paintings were seized by the Nazis in Bordeaux, as were his

gallery and residence in Paris. In July of that year, the German Jewish writer Carl

Einstein, a close friend and supporter of Braque’s, committed suicide in the French

Pyrenees when it became clear that he would be unable to escape the Gestapo.17

Indeed, this period was so unsettling that Braque largely stopped painting and worked

mainly on his sculpture.18 By 1941 he was painting again, and after his initial hardships

and attempts to relocate, he spent the war years in occupied Paris, where he seems to

have managed with great finesse to continue working and to avoid doing anything that

would arouse the suspicions of the Nazis while at the same time keeping his distance

from them.19

FIG. 4

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973)Guernica, 1937Oil on canvas, 137 ½ x 305 ¾" (349.3 x 776.6 cm)

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

20CUBIST STILL LIFE,1928 1945

GEORGES BRAQUE

ANDTHE

20. The scholarship on the role of art and literature in these debates is extensive. For a succinct discussion of the issues as they arose around Guernica, see Susan Rubin Suleiman, “Committed Painting,” in A New History of French Literature, ed. Denis Hollier (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989): 935–42. 21. See Georges Duthuit, “Enquête,” Cahiers d’art, no. 1–4 (1939): 65–73. Cahiers d’art was no strang-er to these debates. In 1937 it had published Picasso’s Dream and Lie of Franco, a series of engravings condemning the atrocities committed by Franco and his troops in the Spanish Civil War, and it devoted most of the next issue to Guernica, then on display at the Spanish pavilion of the world’s fair, and related works; see Cahiers d’art, no. 1–3 (1937): 37–41, and Cahiers d’art, no. 4–5 (1937): 105–56. 22. Such surveys were quite common in French publications before and after World War II, and Cahiers d’art published a number of them over the years.23. Duthuit, “Enquête,” 65.

The Aesthetic DebatesThe nature of the relationship between aesthetics and politics in Europe was one of

the most significant cultural debates in the period leading up to World War II and was

particularly acute in Paris. Questions about the ability of art and literature to effect

political change and about the appropriate form that artistic production should take

had been discussed in French avant-garde journals since the emergence of Surrealism

in the early 1920s, but they became more urgently tied to current events with the

beginning of the Spanish Civil War on July 18, 1936, and the murder of the Spanish

poet Federico García Lorca by General Francisco Franco’s troops in August of that

year. For many artists and intellectuals, García Lorca’s murder raised the issue of

the very survival of art and culture as well as of democratically elected government.

These questions entered the mainstream with Picasso’s creation of the painting

Guernica (1937) for the Spanish Pavilion of the Paris world’s fair of 1937 (fig. 4).

A condemnation of the destruction of the town of Guernica on April 26, 1937, by Nazi

bombers working for Franco, Picasso’s painting combines a semiabstract modernist

style that drew on the legacy of Cubism with a message that was, for some, a clear

critique of the tragic bombing and, for others, difficult to interpret.20 The painting and

its reception spearheaded a heated debate between politically engaged intellectuals

and artists about the ways in which art should mediate between social events and

aesthetic innovation. Picasso and the Surrealists, with whom he was then aligned,

argued for aesthetic autonomy, while for others, including the mainstream Communist

Party, which was then quite influential in France, Socialist Realism, or a mimetic

approach to the representation of real-world events, was the only appropriate

method, and social commentary was a requisite component of all art.

These debates on the relationship between artistic production and political

commitment help shed light on Braque’s work at this time. Although he was known as

a “painter’s painter” and remained essentially apolitical throughout his lifetime, he too

was pulled into these discussions, giving an interview on the topic, which was pub-

lished in 1939 in the deluxe art journal Cahiers d’art.21 His position on these issues

appeared in an “Enquête” (Survey), a series of questions on a particular topic posed to

individuals whose responses were published in serial form.22 For this “Enquête,” the art

historian Georges Duthuit asked five well-known artists—Henri Laurens, Fernand

Léger, André Masson, and Joan Miró, as well as Braque—about the influence of

historical events on their artistic production. The first question addressed the issue

head-on: “Does the creative act reveal the influence of external events, when these

events consist of nothing less than the very annihilation of the forms of civilization that

the painter or the sculptor, more or less consciously, at the beginning of his career,

sets out to enrich?” 23 Duthuit continued, asking if the artwork exists outside historical

UNKNOWNWORLDSAND

THEKNOWN 21

26. Duthuit, “Union et Distance,” 60, 64. The essay referred to Soviet Socialist Realism, which had reached its height in the debates around Guernica, and the Surrealist manifesto “Pour un art révolution-naire indépendant,” which had been signed by André Breton and Diego Rivera, although in reality it was cowritten by Breton and Leon Trotsky in July 1938. If Socialist Realism called for a mimetic art that was immediately understood by the people, Breton and Rivera’s man-ifesto argued that “art must, above all, be judged by its own laws—that is to say, the laws of art.”27. Duthuit, “Union et Distance,” 62. Although Duthuit’s text appeared in the 1939 issue of Cahiers d’art, it was written in 1938, and thus it seems likely that the British critic that Duthuit men-tions was referring to the exhibition Recent Works of Braque at Rosenberg & Helft in London from June 13 to July 13, 1938, or, perhaps less likely, to the Exposition Braque at the Galerie Paul Rosenberg in Paris from November 16 to December 10, 1938.28. Duthuit, “Union et Distance,” 62, 64.

24. Georges Duthuit, “Union et Distance,” Cahiers d’art, no. 1–4 (1939): 60–61. Duthuit explains in the essay that he had asked Picasso to partic-ipate in the “Enquête” but that the artist replied that he had no need to make a public statement as his works spoke for themselves (one assumes that Picasso was referring here to Guernica).25. The Collège de Sociologie was a group of avant-garde writers and artists—initiated by Georges Bataille, Roger Callois, and Michel Leiris—who met to lecture on and discuss aspects of contemporary society. It emerged in late 1937 amid a political climate marked by the extremes of Surrealist anarchist individualism and Soviet collectivism then popular in France, as well as a pervasive sense of betrayal and dissatisfaction with failed politicized models of avant-garde production after the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s. Founded on the belief that a sense of the sacred was missing in the current age of advanced civilization, the Collège de Sociologie was dedicated to exploring phenomena that drew individuals together in voluntary unions that were outside the political realm, such as close-knit communities, brother-hoods, secret societies, armies, and of course art. For more on the Collège de Sociologie, see Denis Hollier, ed., The College of Sociology (1937–39), trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

time; if the artist is in any way dependent on collective social and religious problems or

if, because of his art, the artist exists in a realm beyond that of the average man; and

lastly if there is a bond between the artist and the dominant class that creates the

market and controls patronage. The “Enquête” was introduced by Duthuit’s essay

“Union et Distance,” which addresses both politics—he was an ardent supporter of the

Spanish Republic and critical of the French Popular Front government’s decision to

close the borders to Spanish refugees—and the politicized debates about the function

of artistic production (“as of today, we put in place a series of problems relative to the

position of art in its relationships to the human groupings that compose or decompose

beside us”).24 The combination of Duthuit’s essay and Braque’s responses to Duthuit’s

questions helps position Braque and his still lifes at this time. Duthuit’s essay and the

“Enquête” were illustrated with works by the participating artists, including two of

Braque’s recent paintings: Still Life with Easel (1938; fig. 5) and Studio with Skull (1938;

fig. 6). Like the works then on display at Rosenberg’s, these still lifes are remarkable

demonstrations of painterly virtuosity, and yet the reason for their inclusion is not

self-evident. Resistant to narrative interpretation, with no evidently political subject

matter, they again appear to be self-reflective explorations of the painter’s studio.

Duthuit’s association with the Collège de Sociologie forms the backdrop to his

essay and the “Enquête” and may partially explain Braque’s inclusion.25 If in the essay

Duthuit is searching for a model of artistic practice that can reconcile the needs of

both the collective and the individual (hence the title “Union and Distance”), which was

one of the goals of the Collège de Sociologie, the artists who participated in the

“Enquête” might be understood to stand for Duthuit as potential examples of that kind

of practice. Critical of both Soviet Socialist Realism’s descriptive approach and what he

referred to as the Surrealist “synthesis of the arts, action, and thought,” he seemed to

be searching for an alternative (or perhaps mourning the loss of one) in which “the

plastic arts, music, architecture, poetry, and social man could be joined together in the

service of a common pursuit.” 26 It is therefore reasonable to assume that Braque

appealed to Duthuit precisely because his art appeared apolitical, adding a more

complex dimension to the main question of the “Enquête.” Indeed, Duthuit suggests

that this is the case when he refers to the apparent autonomy of Braque’s work: “Just

yesterday, speaking about an exhibition of Georges Braque’s work, a London critic,

who could not hide his enchantment, remarked on the finesse, the supreme elegance

of this continental production, that is apparently unaltered by the baseness and

horror of the present hour.” 27 Duthuit posed these observations in a more critical light

than the reviewer had but said that he would let the artists speak for themselves.28

UNVERKÄUFLICHE LESEPROBE

Karen K. Butler, Renée Maurer

Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928-1945

Gebundenes Buch, Leinen mit Schutzumschlag, 240 Seiten, 25,5x30,5107 farbige AbbildungenISBN: 978-3-7913-5270-1

Prestel

Erscheinungstermin: März 2013

Neue Aspekte der Forschung, dargestellt in Reproduktionen von höchster Qualität. Als einer der Begründer des Kubismus setzte sich Georges Braque intensiv mit dem Stilllebenauseinander. In seinen Experimenten mit Stillleben und Interieurs erforscht er die Natur derWahrnehmung durch die fühlbare und vergängliche Welt der Alltagsgegenstände. DiesePublikation behandelt einen wichtigen, bislang vernachlässigten Zeitraum – die Übergangszeitvom frühen kubistischen Werk zu den späten großen Serien – und betrachtet BraquesGemälde im kulturellen und politischen Kontext Europas. Die Essays behandeln die Zeit seinergroßen Erfolge in den USA ebenso wie die Rezeption seines Werkes durch die deutsche undfranzösische Kunstkritik.

![Hand in hand [Braque and Picasso] left behind the world of simple appearances.... The two friends worked toward the solution of the same problems, now.](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/56649ed25503460f94be191b/hand-in-hand-braque-and-picasso-left-behind-the-world-of-simple-appearances.jpg)