Yo Loye 1983

-

Upload

marcos-verdugo -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Yo Loye 1983

Inf. J. EducorronolDevelopmenl, Vol. 3. No. 1, pp. 97-104, 1983 0738-0593/83 $3.00 + 0.00

Printed in Great Britain Pergamon Press Ltd

PERSONALITY, EDUCATION AND SOCIETY: A YORUBA PERSPECTIVE*

E. AYOTUNDE YOLOYE

Professor of Education, Institute of Education, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Abstract - Personality has been given several definitions. Nevertheless these may be classified into two categories, namely: (1) as an inner essential nature of man, and (2) as some outward appearance of man. The concept of personality held by the Yoruba people of Nigeria conforms to this dual pattern. The inner essence of personality is known as or; (inner head) while the external manifestation is iwu (character, behaviour). Two other components of the person are pgbon (wisdom) and i;e (work or skill). Ori is independent and the prime motivator of human action. It is conceived of as both the carrier of destiny and as a kind of guardian angel. It is not subject to education. qg)gbpn and is$ on the other hand are the main objects of education. Much of iwa is determined by ori, but education for pgbqn may modify iwu.

Yoruba ontology of motivation stipulates that three factors are responsible for motivating human action: (1) Ori; (2) Aiye - the psychosocial environment; (3) Or&a - the pantheon of deities. Traditional education is mostly informal but some West African tribes operate formal schools known as pore or sun&. Curricula in these schools conform to the Yoruba aims of education, thus confirming that there are probably strong communalities in aims of traditional education among several West African tribes.

Western education has often led to conflicts in the educated individuals. Such conflicts often can be traced to failure to take account of the traditional perception of personality. A closer study of such perceptions of personality in each community may prove fruitful for diagnostic and remedial purposes in educational reform.

INTRODUCTION

The theme ‘personality, education and society’ implies the existence of some interaction between these three significant concepts. Indeed, there is extensive research as well as philosophical literature on each, and most of such literature points to substantial interactions between them. The central concept in this trilogy, however, seems to be ‘personality’.

This paper intends to discuss personality from the perspective of an African society and environment with a view to identifying similarities and differences between this perspective and Western perspectives as reflected in the scientific literature of the West.

It should be emphasized right from the beginning that Africa is pretty large and heterogeneous. While there are several

*Paper originally presented at the 8th Congress of the World Association for Educational Research, Helsinki, Finland, 2-6 August 1982.

97

similarities in culture and history in the various countries, each country must be regarded as also unique. Even with the same country (as in Nigeria) there can be tremendous differences in culture and ecology from one section to the other. Nigeria, for example, has over 200 languages and as many ethnic groups, each with unique features of its own. Therefore, in this discussion, while I may draw examples from various parts of Africa, the main focus will be on Nigeria, and within Nigeria the focus will be on the Yoruba ethnic group to which the author belongs.

THE CONCEPT OF PERSONALITY

There are many meanings given to the term ‘personality’. Meanings vary not only with scholars within one discipline but also between disciplines. Thus for example there are defini- tions peculiar to the fields of theology, philosophy, psychology, sociology and law. Definitions also vary with societies and

98 E. AYOTUNDE YOLOYE

cultures. Thus, for example, while the full range of definitions may be found in many in- dustrialised countries, the traditional meaning in a developing country like Nigeria tends to be of the theological and philosophical variety.

Allport (1937) in a comprehensive review of literature identified 50 meanings. He came up with his own definition as follows:

Personality is the dynamic organization within the in- dividual of the psychophysical systems that determine his unique adjustments to his environment.

(Allport, 1937, p. 48)

In spite of the variety of meanings, two clear patterns were identified (Hunt, 1944, p. 3):

(1) Definition of personality in terms of outward super- ficial appearance of a person (what has sometimes been referred to as the persona or mask).

(2) Definition of personality in terms of the inner essen- tial nature of man.

Studies that have been done on the Yoruba of Nigeria indicate that both patterns of definition are present in the traditional philosophical thoughts of the people. Morakinyo and Akiwowo (1981) provide a review of such studies. Most of such studies have sought the Yoruba explanations of personality and motivation in the philosophical and religious thoughts of the people, as well as in their language. Perhaps the most significant repository of Yoruba philosophical and religious thought is the ifa. ldowu (1962) defines ifa as the geomantic form of divination. In Yoruba mythology Orunmila, the oracle divinity, is regarded as the deputy to Olodumare, the supreme deity, in matters per- taining to omniscience and wisdom. Connected with the cult of Orunmila is a body of oral recitals which belong to the intricate system of divination. These recitals are arranged in self contained chapters each of which is called an odu. The odu corpus numbers 256 and to each odu are attached 1680 stories or myths, called pathways, roads or courses (Johnson, 1899, quoted by ldowu, 1962, p. 8). The odu corpus is referred to as odu ifa and is known by heart by every babalawo, i.e. diviner who is con- nected with the cult of Orunmila. In traditional Yoruba life therefore, the babalawo is a highly respected person. He is the custodian of knowledge and wisdom. He can explain any

events natural or supernatural. He can predict the future. In addition he is an accomplished medical practitioner.

There are of course other sources of Yoruba philosophical thought such as the songs, and folklore. Odu ifa nevertheless stands out as the source par excellence of the wisdom of the Yorubas. What then can be discerned from the odu corpus about the Yoruba concept of per- sonality?

Yoruba on tology of personality Like the definitions in Western literature, the

Yoruba definition of personality considers it as having two components.

(1) Ori. Translated literally, ori means ‘head’. However, to the Yoruba, the physical head is only a symbol of an internal head, ori inu. Ori inu is regarded as the very essence of personality. It is this ori inu that rules, controls and guides the life and activities of the person. The nature of ori inu is determined at the time of creation and thereafter it is unalterable by any human effort. In common parlance, the shortened word ori is used to denote both the internal and the physical head. To the Yoruba, each individual is created separately. At the time of his creation, his ori kneels before the creator and receives its portion (ipin). The por- tion is determined in three ways: partly by a free choice of ori (a kunlc yan); partly by a free gift of the creator (a kunlc gba) and partly by affixation (ayan mo). The Yoruba is of course aware of the biological process of conception and birth. Nevertheless, he believes that the process of creation and the choice of portions takes place for each conception. In practice, ori is credited with a dual role: (1) the essence of personality and controller of destiny, and (2) a protector and guardian. In the latter role ori becomes an object of veneration and worship. If ori is not duly taken care of through worship and consultation, its protection and guidance may be withdrawn for some time and then the individual, left to his own devices, may wander into pathways which were not meant for him and the result is misfortune.

(2) Iwa. In many translations, iwa is equated with the word ‘character’. Similar to what has been found in Western literature, there is a moral/ethical dimension to iwa but there is also

PERSONALITY, EDUCATION AND SOCIETY 99

a dimension that suggests conation. Often iwa is also equated with ‘behaviour’ - not just all actions of the individual but those that occur with consistency, regularity and pattern. Thus iwa approximates to what in Western literature is called ‘personality traits’ but at the same time is the external manifestation of the individual’s personality.

Ogbon. Intelligence is seldom considered as an mtrinsic part of personality. Qgbgn is what closely approximates to the concept of in- telligence. It is, however, more appropriately translated as ‘wisdom’. pgbqn is seen as a func- tion of the physical ori (head). Qgbgn encom- passes all that is necessary for successful adjust- ment in society. In other words, it includes knowledge of the culture, the mores, and the codes of conduct. Thus the knowledge of how to consult ori for guidance is part of qgbqn. Thus while ori inu per se cannot be subjected to training or education, the physical ori can be educated to develop qgbgn.

1;~. Literally translated, if: means ‘work’. Conceptually however, when the Yoruba use the term to refer to a person’s overall en- dowments it is better translated as ‘skill’, par- ticularly occupational skills. Like qgbqn, it: is associated with a physical part of the human anatomy, namely the arm and hand. Most of the traditional occupational skills can, in fact, be located in the arm and hand - farming, hunting, dyeing, cooking, building, smithing, carving, etc.

Thus, in Yoruba traditional thought the four most essential components of the whole person are: (1) Ori; (2) Zwu; (3) Qgbgn; (4) Z?c.

Ori is not subject to development or educa- tion; it is given. Zwa is largely an external manifestation of ori and to that extent aspects of it are not subject to education. However, the Yoruba recognise that being external there is in- teraction between iwa and the environment. So there are also ecological determinants of iwa. To that extent iwa can also be modified. We shall consider the case of iwa in a little more detail presently. Qgbqn and $c are the two components of a person’s make-up that are almost wholly determined by education.

The Yoruba ontology of motivation Motivation refers to the determinants of

human activity. Western literature is rich in

theories of motivation, for example, the psychoanalytic theory (Freud, 1953), the self- actualisation theories (Maslow, 1954; Rogers, 1967) and the stimulus-response theories (Estes and Skinner, 1941; Miller and Dollard, 1941; Mowrer, 1939).

According to Morakinyo and Akiwowo (1981), the Yoruba identify three determinants of human behaviour (the relevant aspect of per- sonality is iwa).

(1)

(2)

(3)

Ori - in this case the internal ori (ori inu) which we have discussed in preceding sec- tions of this paper. Aye - literally translated as ‘the world’ but conceptually it means the psychosocial environment and more specifically ‘people’ in the psychosocial environment. Orisa - meaning the pantheon of gods and other supernatural beings.

Ori. This is regarded as the primary source of all achievement-oriented behaviour. It has activating, energising and directing properties.

Aye. This is usually held responsible for those types of behaviour that are detrimental to the individual’s well-being. In other words, although in theory aye could be responsible for positive events, in practice its role is largely a negative one. Thus aye is usually personified in such creatures as a& (witch) oso (wizard) elenini (antagonists of fellow men’s progress) and olofofo (the ubiquitous gossiper). Explana- tion for individual’s misfortunes and unfor- tunate acts are inevitably sought in aye. Behaviour disorders which would be classified as neuroses or psychoses would be attributed to aye.

Orisa. In the Yoruba religious and metaphysical world, there are believed to be about 400 different orisa each with his or her own distinctive characteristics. Many of the orisa are believed to have once lived as people but became deified as a result of some remarkably distinguished life. All orisa are under the control of the supreme being Olodumare. An orisa may influence an in- dividual’s action by taking possession of him or by responding to an invocation by the in- dividual for his help. Such invocation would usually relate to the expertise of the orisa.

Between them, these three entities determine most of the action and behaviour of the in- dividual.

100 E. AYOTUNDE YOLOYE

It will be seen from the foregoing discussion that the Yoruba interpretation of the structure of personality and determinants of behaviour differ in some significant ways from Western concepts. It is important to keep these facts in mind as we discuss the role of education in per- sonality development.

THE ROLE OF EDUCATION IN PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

In practically all cultures, education plays a significant role in personality development. However, in a developing country like Nigeria, the culture of the people has become increasing- ly difficult to define. One of the significant legacies of colonialism is the introduction of Western education and the Christian religion into the colonised country. The result is that one may identify within the same country three categories of cultures, namely: (1) Traditional - representing the status quo

before the advent of the colonisers. (2) Modern - representing the culture of the

colonial power. (3) Transitional - representing a mixture of the

traditional and the modern. Most illiterates and rural dwellers belong to

the first category. They are still firmly rooted in the traditional thoughts and practices. Most of the educated and the school children belong to category (3) - the transitional. Formal Western education and modernisation have im- posed the Western modes of thought, values and culture on them. Nevertheless, they are still firmly in contact with the traditional through their parents and extended family who mostly belong to the traditional category. Most of the educated still regard their original villages as home irrespective of where they live and earn their living.

There are relatively few people who would belong to the second category, - the modern, in the sense of having completely adopted the Western culture and values. Nevertheless, there are a substantial number who come close to the specifications of this category.

Whether we like it or not, the Western form of formal education has become a part of the cul- ture of developing countries. The major prob- lem of relating education to culture and socie- ty therefore exists with respect to categories (1)

and (3), the traditional and transitional. The various conflicts that arise between education and culture have their origin in the impact of formal education of these people, especially the category (3). In order to understand the prob- lem fully, it is useful to review the role of education in the traditional culture.

Traditional education Using the Yoruba as a case study once again,

we may here recapitulate the structure of per- sonality as traditionally perceived by the Yoruba. We identified four essential com- ponents: (1) ori (essence of personality); (2) iwa (enduring patterns of behaviour); (3) og@n (wisdom); (4) i;$ (skills, especially occupational skills).

Traditional education among the Yoruba was geared towards the development of. qgbon and kc. The development of ygbgn m turn in- fluences the development of rwa although much of iwa is controlled by ori which in itself does not fall within the purview of education.

Majasan (1967; 1975) has written extensively on Yoruba traditional education. He identifies the following agencies of traditional education. (1) Child-rearing practices; (2) Folklores and mores; (3) Organised plays and games; (4) Forms of association and age grades; (5) Formal apprenticeship. In some Yoruba communities, the age grades involve initiation ceremonies which provide more or less formal education in the codes of conduct, social responsibilities and privileges apertaining to the particular age grades. By and large, however, much of traditional education is informal.

In some other West African communities, a greater degree of formalisation of traditional education has existed for centuries. Grimes- Brown (1972) has described extensively formal traditional education among the Grain Coast tribes of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Such educa- tion was given in what were called ‘bush schools’ because they were located in special bushes outside the villages. Two forms of the schools existed, namely, poro for males and sande for females. Because a certain atmosphere of secrecy and mystery surrounded these schools, early Western scholars and mis- sionaries described them as ‘devel-bush’. Later

PERSONALITY, EDUCATION AND SOCIETY 101

insight has shown that they were well organised has been an all-pervading dissatisfaction with formal educational institutions with clearly Western education as inherited from the col- defined curricula. Table 1 below shows how onial masters. The spirit of the discontent is wide spread the bush schools were among the neatly summarised in the following declaration Grain Coast tribes. The schools went by dif- of the Addis Ababa Conference of African ferent names in different tribes. Ministers of Education in 1961:

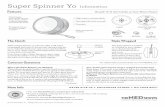

Table 1. Names designating the pore in ten tribes

Tribe Name of the poro Name of the sunde

1. Belle 2. Dey 3. Gbandi 4. Gola 5. Kisi 6. Kpelle 7. Loma 8. Mandingo 9. Mende

10. Vai

Finyer Bohn Polongi Pore (Bohn) Toma Polondo Poro Polongi Kekene Poro, Beli Beli

Sunde Sai Bendei or Sunde Sande (Bondo) Toma Bondo Sannin Zade Musukene Sande Sande

Source: Adapted from The Tribes of the Western Province and the Denwoin People: Bureau of Folkways, Interior Department, 1955,

pp. 15-37 (Monrovia, Liberia).

These schools have existed since the seventeenth century and are still in existence today. Little (1948) has summarised the purposes of educa- tion in these schools as follows: (1) General education in the sense of social and

vocational training and indoctrination of social attitudes.

(2) Regulation of sexual conduct. (3) Supervision of economic and political

affairs. (4) Operation of social services ranging from

medical treatment to forms of education and recreation.

These four aims fit nicely into what the Yoruba would also identify as the aims of education, namely for (tgbqn, isf and indirectly iwa. It does seem, therefore, that although the cultural interpretations of the structure of personality may differ in traditional African societies, there may be considerable similarity in the aims of traditional education.

Interaction of Western education and traditional cultures

If there has been one single thing that has most characterized educational ferment in the new nations of Africa in the last two decades, it

the content of education in Africa is not in line with either existing African conditions, the postulates of political independence, the dominant features of an essentially technological age, or the imperatives of balanced economic development involving rapid in- dustrialization, but is based on non-African background allowing no room for the African child’s intelligence, powers of observation and creative imagination to develop freely and help him find his bearings in the world.

Perhaps some of the statements in that declara- tion sound like over-reaction against the col- onial past. But it does indicate the dilemma of anybody trying to make a change in the system. The problem is how to take account of so many different factors.

A close study of the Yoruba concept of per- sonality and determinants of motivation may help us gain some insight into the real core of the problem, for the problem is still largely un- solved even today.

Education for qgbgn, ig+? and iwa as aims of education are as valid today as they ever were in the traditional society. What has in fact chang- ed over the years are: (1) What constitutes 9gQr (wisdom)? What

was wisdom in the Yoruba society a century

102 E. AYOTUNDE YOLOYE

ago may in fact be foolishness now because the nature of society has changed. The wisdom required to adjust to the simple village life in rural illiterate communities is very inadequate for adjustment in a metro- polis of two million people.

(2) What constitutes $e (skill)? Again the skills required for occupational survival today are vastly different from those required for the simple life of fifty years ago.

Most educators, I am sure, will agree readily with these assessments although when prescrip- tions are made about changes in educational policies, educators and policy-makers alike often act as if they are unaware of these changes. We shall consider some instances presently. But first let us consider if there are certain things about traditional thought and concepts that have not changed.

I would hold that for the Yoruba society, the concepts of the structure of personality and the ontology of motivation have remained largely unchanged, even among the educated. Many social and emotional conflicts owe their origin to this fact. Let us consider two examples.

It is a well-known fact, especially in the Yoruba areas of Nigeria, that the orthodox Christian denominations (Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, etc.) have lost a lot of ground among their converts to a new Africanised version of the Christian religion known by the generic name ‘aladuru’ churches. They conduct their services with a lot of singing, clapping, drum- ming and dancing and lots of lengthy prayers. The features of dancing and drumming clearly fit in beautifully with the Yoruba culture in a way that the dignified hymns of the orthodox churches do not. But it would be a mistake to think that this is the only reason they attract more converts. Perhaps the most significant reason is that in their ministration to the sick and the troubled their methods are based on the Yoruba ontology of motivation. Their methods inevitably involve an attack on and exorcisa- tion of aye. The orthodox Christian religion tends to place the responsibilities for problems on the individual himself and pays scant atten- tion to societal evil-doers - aye. It is well known that most of the converts to the afadura churches joined up in moments of severe per- sonal problems and difficulties for which the

orthodox churches offer no solutions beyond prayers to God.

Of course, the Yoruba recognise the power of the supreme God but they also recognise the powers of aye which must be neutralised before prayers to God can be effective. Many of the leaders of afadura churches have no more than primary education, yet highly educated men in- cluding university professors and top civil ser- vants have joined their ranks as followers.

It is not uncommon for fully trained and qualified medical doctors in times of severe medical problems to turn to the illiterate babaluwo for help. Again underlying this phenomenon is the concept of aye as the motivator of misfortune. Some medical practi- tioners have used this knowledge positively. A prime example is Professor T. A. Lambo who combined Western psychiatric methods with traditional ones to cure the mentally disturbed.

In other words, two major agencies of Western education, the church and the school, somewhere along the line lost contact (or perhaps never made contact) with reality as the Yoruba see it.

In religion, ahdura churches have provided an alternative with greater face validity. The schools have yet to find an alternative. In ef- fect, Western education has created dual per- sonalities in those who have been to formal schools - a Western personality superficially imposed on the traditional one.

Perhaps the area that has been most attacked (and in my view, unfairly) is the effect of Western education on children’s motivation to work with their hands - a revered aspiration of Yoruba traditional education.

The erroneous impression has often been given that African children who have been to school do not like to work with their hands. This is a subjective judgement based on the reluctance of children who have been to school to return to farming. Some research evidence available indicates that these children, although they do not wish to farm, do not necessarily dislike working with their hands.

Calcott (1968), as part of a bigger study in the former Western Nigeria, administered a questionnaire to a sample of primary six children in which the children were asked to choose what occupations they would like to go

PERSONALITY, EDUCATION AND SOCIETY 103

on to after primary school. Their choices were Table 4. Occupational aspirations and expectations of

as shown in Table 2. Ghanaian secondary school students

Table 2. Occupational aspirations of primary six children, Western state Nigeria

Occupations Aspirations Expectations % choosing % choosing

Occupation % Choosing

Farmers 0.7 Craftsmen and artisans 21.2 Trades and businessmen 3.4 Professionals, clerks, etc. 30.0 Others 8.0 Further education 36.6

Professional (law, medicine, etc.)

Scientific and technical Clerical Secondary school

teaching Teaching at lower levels Farming and fishing

20.7 0.1 21.7 6.1

1.5 51.9

16.4 1.3 5.3 32.4 1.3 1 .o

The results suggest that what the children dislike is not working with their hands per se, but specific occupations. They do not like far- ming (0.7%) but they would like to be crafts- men and artisans (2 1.2 Vo). The operative factor is not the mode of working but the acceptability of the occupation.

In terms of aspiration, professional, scien- tific and technical occupations rate high (20.7% and 31.7%) while clerical rate low (7.5%). In terms of expectations, however, the positions are reversed with clerical now rating very high (50.1 O7o). Interpreting these data, Foster says:

Silvey (1969) in a similar study in Uganda using secondary school students in the school certificate year got the responses indicated in Table 3.

Table 3. Occupational aspirations of Ugandan secondary school students

Occupation % Choosing

Professional (medicine, law, etc.)

Commercial or administrative Scientific and natural

24.7 4.3

Our evidence suggests that critics who have implied that African students are unrealistic in their vocational ex- pectations or wish to enter only clerical and white-collar employment are generally incorrect. They have not realized what these students appear to perceive, that there are few openings in the occupational structure apart from this kind of employment. . Ultimate occupational destination may of course be partly in- fluenced by vocational preferences but in the last resort, it is determined by the structure of job opportunities in the economy. By a process of post-hoc reasoning it has been assumed that vocational destinations reflect the real aspiration patterns of students more often than not people are obliged to accept jobs that do not feature very highly in their plans.

resources 18.5 Technical 10.9 Teaching 14.0 Social work 4.7 Farming 0.4 Others 21.7

The search for relevant education

Similar results have been obtained by Foster (1965) and Foster and Clignet (1966) in Ghana and the Ivory Coast respectively.

A lot of progress has been made in the new nations of Africa in their search for greater relevance in education. National curriculum development centres have been created in most countries. As many as 20 national centres spread through as many countries in Africa now belong to the African Curriculum Organisation (ACO)‘. But the search has been focussed on environmental conditions.

Contrary to common belief, general commer- cial and administrative posts are not popular in terms of aspirations (4.3%). Foster (1965) in his Ghana study made a distinction between aspira- tions and expectations of secondary school students. His results showed different patterns for these two as indicated in Table 4.

When educationists have attempted to do something with the personality of the in- dividual, they have, I am afraid, often missed the point. Consider the case of ‘working with the hands’ discussed in the preceding sections, for example. Educationists and policy-makers have attempted to tackle what they perceive as the problem by preaching something called ‘the

104 E. AYOTUNDE YOLOYE

dignity of labour’ to the pupils. They implicitly Conference of African States on the Development of

equate labour with manual labour, and attempt Education in Africa (1961) Addis Ababa, 15-25 May,

to exalt it by cloaking it with some abstract Final Report, UNESCO, Paris.

dignity. If we were to go back to the Yoruba Estes, W. K. and Skinner, B. F. (1941) Some quantitative

properties of anxiety. Journal of ~x~r~me~tai concept of .i.sc, however, we will note that you Psychofogy 29, 390-400.

can genuinely talk of the ‘dignity of ise’. Zse Foster, P. J. (1965) ~dacatjo~ and Social Change in

was inevitable for survival of the indi;‘idual. Ghana. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

But remember that i;e is more correctly Foster, P. J. and Clignet, R. (1066) The Fortunate Few: a

translated as occupational skill and not as Study of Secondary Schools and Students in the Ivory Coast. Northwestern University Press, Chicago.

‘manual labour’. It is true that in former times, Freud, S. (1953) The Complete Psychological Work oj

occupational skills were also mainly manual Sigmund Freud, Vol. VII. Hogarth Press, London.

skills. Today the occupational skills that max- Grimes-Brown, M. A. (1972) Education among the Grain

imise the chances of survival are very often not Coast tribes. In Foundations ofAfrican Education, Vol. 2. The Drive towards ~odern~zatjon (edited by Yoloye,

of the manual kind. Many of them are intellec- E. A. & Nwosu, S. N.) pp. 208-234. Ibadan WACTE

tual. If educationists operated from the basis of (mimeograph).

this insight (which, by the way, the pupils have Hunt, J. McV. (ed.) (1944) Personality and the Behaviour

no difficulty in achieving) more attention Dfsorders. The Ronald Press Co., New York.

Idowu, E. B. (1962) Olodumare: God in Yoruba Belief. would be directed to the relevant skills rather William Clowes, London.

than some non-functional concept like the Johnson, J. (1899) Yoruba Heathenism. James Townsend,

‘dignity of labour’. The concept of the human London.

personality as seen in particular cultures may Little, K. (1948) The poro society as an arbiter of culture.

have significant implications for education. As African Sfudies 7, 3.

Majasan, J. A. (1967) Yoruba education: its principles,

the foregoing discussion has shown, closer at- practice and relevance to current educational develop-

tention to such personality perceptions may be ment. Unpublished Ph.D Thesis, University of ibadan.

very fruitful in more meaningful diagnosis of Majasan, J. A. (1975) Indigenous Educution and Progress

educational problems and therefore in initiating in Developing Countries. Ibadan University Press, Ibadan.

solutions. Maslow A. (19.54) Motivation and Personality. Harper & Row, New York.

NOTE Miller, N. E. and Dollard, J. (1941) Social Learning and

1. The African Curriculum Organisation (ACO) is an association of nationally recognised Curriculum centres in Africa. Its secretariat is in the Institute of Education, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Countries represented are Botswana, Cameroun, Congo, Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Mauritius, Nigeria, Sierra-Leone, Somalia, Swaziland, Tanzinia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Imitation. Yale University Press, Newhaven. Morakinyo, 0. and Akiwowo, A. (1981) The Yoruba

ontology of personality and motivation; a multidisciplinary approach. Journal of Social and Biologicaf Structures 4, 19-38.

Mowrer, 0. H. (1939) A stimulus-response analysis of anxiety and its role as a reinforcing agent. Psychological Review 46, 553-565.

Rogers, C. (1967) On becoming a Pelson. Constable,

REFERENCES London.

Silvey, .I. (1969) The occupational attitudes of secondary Allport, G. W _ (1937) Personality: a Psychological lnter-

pretafion. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York. Calcott, D. (1968) Interim Report, ‘Education in a rural

area of Western Nigeria’. Ministry of Economic Plan- ning and Social Development, Ibadan.

schooi leavers in Uganda. In Research and Action Educa- rion it? Africa (edited by Jolly, R.) pp. 135-153. East Africa Publishing House, Nairobi.