Yentl

description

Transcript of Yentl

-

YentlAuthor(s): Stephen J. WhitfieldSource: Jewish Social Studies, New Series, Vol. 5, No. 1/2, American Jewish History andCulture in the Twentieth Century (Autumn, 1998 - Winter, 1999), pp. 154-176Published by: Indiana University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4467547Accessed: 11/05/2009 16:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=iupress.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with thescholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform thatpromotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Jewish SocialStudies.

http://www.jstor.org

-

Yend

Stephen J. Whitfield

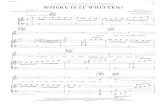

W4 A There is it written what it is I'm meant to be?" This is the nearly monosyllabic question that Barbra

Streisand sings in Yentl (1983) and that resonates through- out the film, which opens with the camera lingering over shelves of books. Her eponymous protagonist defies the rigidity of gender roles, as prescribed in the "Eastern Europe" of 1904, even as her query implicitly denies that her cherished texts prohibit study for females like herself. But Yentl indirectly gives another answer to her own question, which is that she need not be only what Isaac Bashevis Singer meant her to be. The cinema is different enough from books to honor its own aesthetic and historical imperatives; an art form that has its own fluid logic need not be confined to what is inscribed in his story 'Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" (1962).

In such differences might be noted a clash between the Old World and the New, between the seriousness of the literary vocation and the prerogatives of box-office stardom, and even between the sensibilities of a Warsaw-born man and a Brooklyn-born woman a generation younger. In addition, how a work of fiction was transformed into Yentlprovides an entree into the conditions under which an AmericanJewish culture has manifested itself. That transformation is exemplary because of the disorder-of something out ofjoint-that Singer's story itself recounts. Perhaps like all unsettling stories and folktales, "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" involves transgression; its protagonist is so fine a student that her father liked to say to her: 'Yentl-you have the soul of a man." "So why was I born a woman?" "Even Heaven makes mistakes." She is portrayed in masculine terms, with her flat chest, her narrow hips and her upper lip even betraying "a slight down."' This "yeshiva boy" is entangled in a web of duplicity in order to satisfy an illicit passion for knowledge; to bring that story to the screen, Streisand risked charges of betrayal and infidelity

-

to Singer's original tale-and even to the distinctive ambience from which it had sprung. Yentl did not necessarily show the way we were. Yet the dangers of transgression against the authority and authenticity of the Judaic past seem unavoidable in a culture that has propelled itself so far from the austerity of Talmudic study. The refusal to be confined-either by the religious norms that a deceitful Yentl violates or by the genre in which her fate was first imagined-is one way of summarizing the individualism and experimentalism of the national ethos that Jewish immigrants and their descendants have so strikingly honored, rein- forced, and revised.

The invocation of personal freedom and assertion-from the impris- onment of poverty, or from the conventions of what a movie star supposedly looks like, or from the cramped expectations that lower female aspirations-is an irrepressible feature of Streisand's own life. To one interviewer she revealed the searing intensity of her ambition to surmount the material deprivation of her upbringing:

I had to make something of myself. I lived in those movie theaters, and went out into the hot humid Brooklyn streets, and went home to an apartment where there were three children. I didn't have my own room until I was thirteen! We didn't have a couch until I was eight. We had a dining room; we used to sit around the table. My brother slept on a cot that folded out; my mother and I slept in the same bed. I didn't have luxury. My grandmother, my grandfather, my brother, me and my mother all shared a bathroom. A couch to me was an amazing thing.2

Broadway stardom came barely past adolescence, with Funny Girl (1964), in which Streisand's opening song was a poignant ballad called "If a Girl Isn't Pretty"-a condition that does not disqualify "Fanny Brice" from her inalienable right to pursue happiness.

So spectacular was this debut that one drama critic was incited to speculate that, if New York were Paris, Broadway would have been renamed the Rue Streisand. Adapting a hit musical devoted to the theme of show-business success had the aura of cinematic inevitability- as was the casting of the lead, even though Streisand refused to change her name or even to take a screen test (thus blocking any suggestions of rhinoplasty). Stardom in Hollywood would be won on her terms-or rather on Sir Francis Bacon's: "There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion." There would be no surgical solution to the Jewish Problem that Moses Hess identified in Rome and Jerusalem: a nose with deviations was a crime against the German nation, which often "objects less to the Jews' peculiar beliefs than to their peculiar noses."3 By winning an Oscar for Best Actress in Columbia

[155]

Stephen. Whitfield

Yentl

-

Pictures' Funny Girl (1968), Streisand revised the definition of glamour; within a year, she chanced upon Singer's short story.

Its opening four words ("After her father's death") hooked her and activated her determination to bring "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" to the screen; Emanuel Streisand, a high school English teacher and part-time melamed, had died when she was only 15 months old. The fable of barriers being scaled moved Streisand to tell her agent, David Begelman, "I just found my next movie." Screen rights were optioned in 1969, and had Yentl indeed been her next vehicle, when she was in her late twenties, playing a character a little more than a decade younger, then it would have been a drama financed on a small scale, an opportunity to stretch her acting skills. Had any studio seen fit to bankroll a film that in modesty of production and sobriety of tone would have conformed to the short story, much of what later looked problematic would never have hap- pened. But every studio passed at least once on a project so preposterous that a New York Times headline-writer joked: "A New Movie for Barbra: 'Funny Boy."'4

Even when a woman rose to the top of Twentieth Century-Fox, the answer was no. President Sherry Lansing, whose own mother had fled Nazi Germany, could not conceive of such a story as universal enough to fill seats in, say, the Mississippi River Valley or as commercial enough to appeal to the fans of a star who would be pretending to be a boy. "I left the office in tears," Streisand recalled. "I couldn't believe that a woman wouldn't understand." Under the older studio system that the moguls had installed, such a film would have been unimaginable. Under the new dispensation, ingenuity and tenacity were needed to get an unusual project through the maze-and she was failing, especially because Yentl was intended to launch Streisand's career as a director too. Then, a full decade after screen rights had been purchased, she and her brother Sheldon went to visit their father's grave at Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens, and they noticed that the next tombstone was inscribed with the name Anschel. It was the very name that a masquerading Yentl takes as her own, allowing Streisand to decode "a sign from my father that I should make this movie." More earthly aid was provided by her friends, lyricists Marilyn and Alan Bergman, who argued that the project would work as a musical. After Yentl's father dies, she has no one "to whom she can reveal her essential self. And this rich inner life becomes the [song] score," Marilyn Bergman conjectured.5 Music would also convey an atmosphere of surreal magic and lower any audience expectations of ethnography, even though a musical in which the director gives only one member of the cast a chance to sing risked charges to which Streisand was hardly immune: egocentrism.

[156]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

But such an accusation mattered less than potential studio interest. If the most popular female vocalist in American history would abandon the idea of a small dramatic movie, then Yentl would be bankable. Especially after Singer received the Nobel Prize, such a film would provide the respectability that is not utterly foreign to the ambitions of even the producers of blockbusters. The choice Streisand faced was between a film that seemed destined only for the art houses, which meant that it might never be done at all, and the lavish and lush musical that she finally agreed to make. However distant from Short Friday and Other Stories, such a film would at least tap what music critic Stephen Holden called Streisand's "mysterious ability to personify the fullness of human experience when she sings. Instantly recognizable, her voice, at once beautiful and emotionally exacerbated, has always conveyed an innate imperiousness and an intense yearning." Her "primal" gift is a "supreme dramatic command," which can "take a flowery romantic ballad and make its sentiments seem ineffable, transcendent."6

Such a power is not teachable-but Judaism itself is. Having met Chaim Potok, Streisand decided to prepare for the film by taking Talmud lessons over a three-year period-the same length of time she had spent in a Jewish day school in Brooklyn (from the ages of five to eight). Potok called her command ofJudaism "confused and rudimen- tary. Yet she asks questions openly, unself-consciously, with no hint of embarrassment.... I have no way of gauging her comprehension. Her mind leaps restlessly, impatiently, from one subject to another." Streisand herself also made much of the distinction between an obligation to study, whichJudaism historically imposed only upon men, and a prohi- bition upon female learning, which the Talmud does not make em- phatic.7 The effort to bring "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" to the screen remained stalled, however, even as her own ambitions grew. Singer became testier, doubting that any "human being ... [would] have all the qualifications. She cannot be the actress, the producer ... but she chose this way. So, if she succeeds, I will consider it a miracle." Orion Pictures disagreed; by promising to contain costs to $13 million, Streisand could star in, direct, produce, and write the film. But when a $38 million Western called Heaven 's Gate tanked at the box office in 1980, Orion got so terrified of expensive films that it tore up its contract with Streisand. Only after her former agent Begelman took charge of United Artists did she finally get the chance to make her movie. The script, which was co- credited to British playwright Jack Rosenthal, eventually required 18 rewrites. Yentl still looked so unpromising that Richard Gere turned down the role of Anshel's study partner, Avigdor, and Carol Kane, who had playedYekl's wife Gitl inJoan Micklin Silver's Hester Street (1975), was

[157]

Stephen. Whitfield

Yentl

-

unavailable for Hadass. By the time principal photography was com- pleted, in October 1982, the 40-year-old actress ended up playing a 28- year-old woman masquerading as an adolescent boy.8

But perhaps the miracle had occurred after all. When Streisand showed a cut of the finished film to Steven Spielberg, his advice was crisp: "Don't change a frame." When Yentl opened in November 1983, News- week's David Ansen announced that the director had given its star "her best vehicle since Funny Girl," and The New Yorkers Pauline Kael praised the film as "rhapsodic yet informal" and mostly "glorious." The $20 million production grossed $50 million in the United States and as much abroad, and about three million customers bought the sound- track album. Indeed, Michel Legrand won an Academy Award for Best Original Film Score, though Streisand won nothing on Oscar night-a shut-out that amplified Hollywood's earlierjudgment that her taste was narrowly musical. No one, however, took more initiative to try to torpedo this international hit than Isaac Bashevis Singer, who absorbed the shock of recognition by proclaiming his own recognition of shlock. Interview- ing himself for the Arts and Leisure section of the New York Times, he offered three reasons for his hostility to the transformation of "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy": the introduction of singing, the substitution of a different ending, and in general the imperiousness and tastelessness of "those who adapt novels or stories for the stage or for the screen," who "must be masters of their profession and also have the decency to do the adapta- tion in the spirit of the writer."9

What was appealing to Hollywood was anathema to Singer, whose short story "was in no way material for a musical, certainly not the kind Miss Streisand has given us. Let me say: one cannot cover up with songs the shortcomings of the direction and acting." He was unable to "find anything in her singing which reminded me of the songs in the study houses and Hasidic shtibls, which were a part of my youth and environ- ment. As a matter of fact, I never imagined Yentl singing songs. The passion for learning and the passion for singing are not much related in my mind. There is almost no singing in my works." Biographer Janet Hadda speculates that such an objection stemmed from the sense of impropriety implanted in the Talmudic fear that the solitary female voice is sexually alluring.10 Though unobservant himself, he may thus have acknowledged in a residual way the halakhic rule against women singing alone in public.

A very strict interpretation of kol ishah ("the voice of a woman") would have impoverished the nation's musical life by blocking the career of an artist like Beverly Sills. According to one Orthodox authority, "a woman's singing voice, under all circumstances, is to be considered a form of

[158]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

nudity, to be exposed exclusively to one's husband." What are those circumstances? "The identification of a woman's voice as a likely source of sexual stimulation has led many modern halakhic authorities to ban, albeit with substantial dissent by other authorities, activities such as choirs of men and women together, women singing zemirot in the presence of men other than their husbands, listening to records of women singing, and even women singing lullabies to their children in the hearing of men." For the 30-day anniversary to memorialize the murder of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, held in Madison Square Garden, Orthodox groups threatened to pull out were Streisand to sing- according to a report of her intentions-"Ha-tikvah" as well as the peace song sung at the rally in which the Israeli prime minister had been killed in Tel Aviv. "We were promised no women singing," according to Rabbi Pesach Lerner, executive vice president of the National Council of Young Israel. Dr. Mandell Ganchrow, president of the Union of Ortho- dox Jewish Congregations of America, warned that "having a female soloist might present an unnecessary obstacle."1 (She did not partici- pate after all.)

Singer himself claimed thatYentl would hardly have sung in aYeshiva. Though she deceptively dressed as a man to satisfy her yearning for learning, the author insisted, she otherwise did not intend to flout Judaic law. His objections are not convincing. Never mind thatYentl's 11 songs are sung only to herself; she does not sing in public. Characters do not croon at one another, which requires the suspension of disbelief in musicals other than Yentl. But odder is Singer's insistence that his protagonist's male disguise represents the only shock to the system, that no other anomalies (or perversities like singing) would have been in character. Indeed, Singer's Anshel realizes that, in asking for the hand of Hadass and becoming a groom, she "warned herself that what she was about to do was sinful, mad, an act of utter depravity. She was entangling both Hadass and herself in a chain of deception and committing so many transgressions that she would never be able to do penance."12

Even if Singer were correct in tabulating only one anomaly, the blurring of gender lines constitutes so bizarre a breach that it is tempting to enlarge the list that Richard J. Israel compiled under the rubric he labeled "the kosher pig." This conundrum of AmericanJewish life stems from

attempts to apply the classic categories ofJewish law to new situations. The problem is that the questioners either do not know about or have rejected some of the most basic presuppositions of the Jewish legal system. There is something about the premise of their questions that prevents a halakhic

[159]

Stephen . Whitfield

Yentl

-

answer, an answer according to traditionalJewish law, from being given. The puzzle we are left with is: Can the halakha be applied to non-halakhic questions or must we rely upon the punch line of the old joke and say that you can't get there from here?

Near the end of the twentieth century, queries associated with intermar- riage posed to American rabbis like Richard Israel are paradigmatic: "Rabbi, I am marrying an Episcopalian woman, but I want to include the traditional seven blessings of the Jewish wedding in our ceremony. Do they have to be in Hebrew or can I translate them into English?" Or: "Does the prohibition against weddings during the period between Passover and Shavuot (The Feast of Weeks) apply to our upcoming intermarriage?" Or an unmarried Gentile who is having an affair with a Jewish man is led to wonder: "Is it against his religion to sleep with me when I am having my period?"13 Since "Anshel" is not entitled to study the Talmud in an all-male sanctuary anyway, the interdiction of kol ishah seems irrelevant.

The conclusion that Singer gave his tale is suffused with entrapment and estrangement. At Avigdor's suggestion, Hadass learns from a mes- senger bearing papers of her divorce from Anshel, who has vanished. Now free to marry her, Avigdor divorces his own wife Peshe to marry Hadass, igniting much gossip among the townspeople. When a son is born, "those assembled at the circumcision could scarcely believe their ears when they heard the father name his son Anshel." Though "he" is in effect reborn, the transvestite herself is compelled to wander. She needs to escape detection, but she cannot get rid of her disguise (and become merely Yentl) because she remains desperate to continue her Talmudic studies.14 Singer's ending is bleak and inexorable, and it forecloses any attractive options.

But "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" is set in a shtetl called Pechev, and Yentlwas made in the United States. As William Dean Howells informed Edith Wharton, when the dramatization of her novel The House of Mirth failed in New York: "What the American public always wants is a tragedy with a happy ending." Streisand's Yentl does not seem trapped at all. She crosses an ocean in an effort to separate past from present, and on the ship is back to wearing female attire. She is herself again. But "was going to America Miss Streisand's idea of a happy ending for Yentl?" Singer wondered. Why could the protagonist not have found numerous other Yeshivas in Lithuania or in Poland that would have harbored "Anshel"? The novelist inquired further: "What wouldYentl have done in America? Worked in a sweatshop twelve hours a day when there was no time for learning? Would she try to marry a salesman in New York, move to the

[160]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

Bronx or Brooklyn and rent an apartment with an ice box and dumb- waiter?"15 For an impoverished Jewish scholar of whatever gender, he suggested, the United States was no promised land. Although Alma Singer should not be regarded as an authoritative reader of her hus- band's fiction, she concurred: "This going to America ... has absolutely nothing to do with what was intended." Even Kael felt betrayed: "It feels almost like a marketing choice," the point of which was "to give the movie audience hope." The dilemma that Yentl faces seems unresolv- able: "One moment, Yentl is a yeshiva boy, taking pleasure in being the smartest kid in the class; the next moment, she's got herself in a fix. There's only one end to this story, and it's the one that Singer gave it: Yentl must go down the road in search of another yeshiva. She is condemned to the life of study that she has chosen." Finally, Kael added, "the closing shipboard sequence seems a blatant lift from the 'Don't Rain on My Parade' tugboat scene in Funny Girl; it feels like a produc- tion number, and it violates the whole musical scheme of the movie."16

But here, too, at least a partial defense can be mounted. If movies must at least move (whatever else they do), then a logic to Yentl's trajectory can be traced: from an unnamed shtetl to a larger but still obscure town, then to Lublin, and finally across the Atlantic to another continent, where at its other end Hollywood would develop the tech- niques of retelling such stories. She would have immigrated at the precise historical moment when theJewish moguls who had themselves come from Eastern Europe were disentangling their medium from "such non-literary amusements as travelogue and natural-history lec- tures, live musical entertainment, circus performances, vaudeville acts, and the like," film historian Joel Rosenberg has observed, and were adapting literary and dramatic works to give primacy to narrative.'7Yentl is heading in the direction of the place that would add new curlicues of self-reflexivity in the act of story-telling.

Moreover, to protest the rousing musical finale is not necessarily to discredit what has come before. Yentl is no more "ruined" by "A Piece of Sky" than the high-jinks and phony bravado to which Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer subject the already emancipatedJim spoil The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Nor should Streisand's ending be read as unambigu- ously happy. By revealing her breasts to Avigdor, she has, after all, lost him. Her study partner is a conformist unwilling to challenge the rigidities of gender ("This is crazy: I'm arguing with a woman"), nor can he fathom why Yentl would still need to pore over the Talmud (though he offers her a furtive nocturnal syllabus), nor does he conceive that he (or halakhah) could change, nor does booking passage to America occur to him. Therefore she is all alone. In Alfred Kazin's recollection of

[161]

StephenJ. Whitield

Yentl

-

the legacy of the shtetl, "the most terrible word was aleyn." That could be the fate of Streisand's Yentl for having opted for scholarship over marriage-even marriage to Avigdor, who cherishes the devotion (and succulent dishes) of the very unliberated Hadass. "No wonder she suits him," Anshel sings; "she never disputes him."18

The camera finishes its movements by following Yentl on her own, bereft of friends or relatives, "going to new place, where I hear things are different." (The country itself remains anonymous.) She has only heard of its advantages; but nowhere, she implicitly acknowledges, is it written that life is better in the United States. "Anyway we'll see" is her wary expectation of a land where the American Adam could start afresh, outside the groove of tradition, without the deadweight of institutions. The destiny of the American Eve is left dangling, however. But by heading for the New World, the cinematic Yentl will presumably be able to test rumors by experience, and there truths will have to be self- evident. There the impetus of personal ambition could not be placed "under strict rabbinic supervision," and the perpetuation of communal authority would yield to the ideal of autonomy. What better place to find individual fulfillment, "to see myself, to free myself, to be myself"? The choice of the United States was neither eccentric nor senseless for a woman who seeks a wider sphere for her own piety than what the Old Country appears to offer. Even if still considerably east of Eden, America was a loophole-and a more accessible recourse than Palestine. In leaving Warsaw, Pauline Kael's own parents and, later, Singer himself found a refuge that was statistically far more probable than was the Yishuv.

An imperfect democracy offered a promise not least for those who felt stifled in the gender roles that normative Judaism had presumably assigned them. Exactly a century after the Declaration of Independence, Isaac Mayer Wise denounced in the American Israelite the confinement of woman to "a garret in the synagogue, isolated like an abomination, shunned like a dangerous demon, and declared unfit in all religious observances," and he ostensibly introduced the family pew to help erase gender differences "in regard to duties, rights, claims and hopes." By the end of the century, women in Philadelphia were taking advanced courses in Judaism at Gratz College, the first of the nation's Hebrew teachers' colleges to offer such a curriculum without distinguishing women from men. When Streisand's Yentl asserts that "learning is my whole life," she might have been speaking for the young Henrietta Szold, whose devo- tion to scholarship could be honored without having to cross-dress in translating much of Louis Ginzberg's Legends of the Jews, in serving as editor of theJewish Publication Society of America, and in assuming the

[162]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

editorial responsibility for the American Jewish Year Book. To be sure, she had to assure Solomon Schechter that her sole intention in seeking admission to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America was to study and not to become a rabbi.19

Lesser figures might also be mentioned. Though far from serving as a forum for Talmudic scholarship, The American Jewess, which Rosa Sonneschein edited from 1895 until 1898, began to elevate the status of women in the decade before the plot of Yentl unfolds. Another prece- dent had been established by the San Francisco-born Rachel (Ray) Frank, whose sobriquets included "The Girl Rabbi" and "The Female Messiah." In Spokane, circa 1890, she might have been the first woman in history to preach from the bimah on the High Holy Days. Mostly in the West, she continued to deliver sermons and addresses in praise of the religion to which the Jewish family and Jewish women were indebted. Given the honor of delivering the opening prayer at theJewish Women's Congress during the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Frank was no counterpart to Yentl, and she was closer in her homiletical style to Protestant revivalist preachers than to the piety of Yeshiva boys. Nor was she much of a proto-feminist; when she married in 1898, her public career virtually ceased.20 She cultivated charisma and explored "spirituality" in ways that were of no interest to Yentl. But Frank's vocation-as well as Szold's and Sonneschein's-suggested a plasticity and inclusiveness to fin-de-siecle American Judaism that makes the finale to Yentl cogent though not inevitable.

In accusing Streisand of infidelity to a story that had been published over two decades before her film was released, Singer located the larger cultural question of how novelists should confront the movie industry. Notorious for paring away subtleties and complexities for the sake of maximizing intelligibility and accessibility, Hollywood was personified in a producer likeJerry Wald, a real-life Sammy Glick, whom an interviewer described as "plump, baldish, cigar-chewing"; Wald "talks rapidly and freely on any topic." When Ulysses was mentioned as a promising film, he quickly retorted: "I got an option on it! It's basically just a father searching for a son. Universal theme!" So coarse are such reductive proclivities that one can only guess at the speed with whichJoyce was sent spinning in his grave, but Singer was at least able to exert some damage control when his own literary property was threatened. His predica- ment, however, was that the screen rights to 'Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" had been sold-and no one is known to have held a gun to the novelist's head in relinquishing them. Singer wanted it both ways-the big bucks that Streisand paid for the opportunity to adapt the short story (though he complained that her acquisition had been "a bargain") and the custodial

[163]

Stephen. Whifield

Yent Yenfd

-

high ground from which to scorn the results of vulgarization. "First, I'll see the killing," he had warned before Yentl was released, "then I'll perform an autopsy."21

Singer's attitude might be contrasted with the stances of other novel- ists. After an initial mistake with "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut," J. D. Salinger adopted a stance of purism and adamantly declined to enrich himself from the "goddam movies," which Holden Caulfield insists "can ruin you. I'm not kidding." Or consider the complaisance of Vladimir Nabokov, who acknowledged the considerable liberties taken not only with the nymphet in Stanley Kubrick's Lolita but also with the screenplay with which the novelist himself was credited. He nevertheless praised the artistry of the director, whose changes included material Nabokov wished had been in the novel. Graham Greene preferred to take the money and run, and he saw no point in "go [ing] through the unpopular motions of fighting every battle lost at the start.... No, it is better to sell outright and not to connive any further than you have to at a massacre. Selling outright you have at least saved yourself that ambiguous toil of using words for a cause you don't believe in." Greene's advice to impecunious writers was simple: 'You rake [in] the money, you go on writing for another year or two, you have nojust ground for complaint." After all, he noted in 1958, a Hollywood producer "can turn your tragedy of East EndJewry into a musical comedy if he wishes."22

Perhaps the repertoire of narratives that our species recounts to itself is somewhat limited after all, but show-business operators like Wald helped to account for Professor Allan Bloom's valorization of literature. His best-seller indicted the fondness for movies as symptomatic of students' failure

to distinguish between the sublime and trash, insight and propaganda.... The distance from the contemporary and its high seriousness that students most need in order not to indulge their petty desires and to discover what is most serious about themselves cannot be found in the cinema, which now only knows the present. Thus, the failure to read good books both enfeebles the vision and strengthens our most fatal tendency-the belief that the here and now is all there is.23

Such put-downs of a medium in which artists have worked and which manages to satisfy the hunger for sublimity of many intellectuals is quaintly snobbish, a reactionary battle cry that long ago ended in defeat. Such an effort to grade one art form as superior to another would certainly not make sense if applied elsewhere: is Othello better than Verdi's Otello, or Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet better than Tchaikov-

[164]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

sky's? It is possible to mourn the eclipse of literacy without disdaining an art that offers many other satisfactions, or without feeling a compulsion to rank what can be achieved with quite different means.

Works of literature are not obviously superior to how they might be transferred to celluloid, which in any event lacks the power to cancel out what readers find stimulating and indispensable. To be sure, some adaptations are ludicrous. The well-meaning producers of the best- selling Native Son promised Richard Wright to respect the original, except for one minor change: they wanted to make Bigger Thomas a white man. Some adaptations vastly improve their originals; only schol- ars of racism in the post-Reconstruction South bother to read the fiction of Thomas Dixon that inspired the alchemy of D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation. L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is still cherished, though no longer read as a parable of Populism, and yet the world of childhood (and even adulthood) is a little more enchanted because of MGM's The Wizard of Oz. The 1939 musical has not displaced the novel, which makes no mention of a rainbow; lyricist 'Yip" Harburg inserted that symbol of hope for a different era. When film adaptations click, cultural life is enlarged rather than shrunk, enriched rather than per- verted. Those who fear what successful movies do to the original stories betray an unwarranted fear that the shelves have been emptied of books to be read and pondered, that the temperature of our culture has already reached the Fahrenheit 451 at which book paper will reputedly burn.

Interestingly enough, Singer did not criticize Yentl for its unfaithful- ness to the world of learning that the film casts in such glowing terms. But this movie has been subjected to two additional objections: that it is insufficiently serious about Judaism, and that it is insufficiently serious about feminism.

For example, even though Yentl surely provides the first Hollywood soundtrack to be punctuated by the names of such sages as Hillel and Rabbi Israel Salanter, the literary scholar David Roskies, for example, was struck by how rudimentary is the discussion among Yentl and her peers-such as Hillel's famous question (from Tractate Avot of the Mishnah) that begins, "If I am not for myself.. .": "This is about the sum total of what Streisand could've imagined a Talmudic argument to be ... Any chederboy knows about this." In an incisive scholarly critique, historian Felicia Herman finds that

[T] he film reduces the complex system ofJewish law to a single axiom: if it is written, it holds authority. Aside from implying a complete rejection of the authority of minhag (custom), this simplification also assumes that there

[165]

StephenJ. Whitfield

Yentl

-

is one single place where Jewish law is "written." Does Yentl follow only the laws in the Torah? What of those in the Talmud? Or later rabbis' commen- tary? The Shulchan Arukh? The film ignores these questions.

Other than study, no other forms of Judaic expression are conveyed. Yentl is shown taking over the recitation of the mourners' kaddish at her father's grave site, and later kneels rather than stands in prayer when alone in the forest right after her flight from home. Both scenes, Herman adds, would be "problematic" for traditionalJews.24

Although Yentl becomes Anshel a year after the Kishinev pogrom, bigotry is absent from the film, which depicts Gentiles in only one brief scene (in which Anshel is tricked by peasants on a cart). The careful avoidance of any allusion to oppression, Herman suspects, may have left audiences puzzled to see so many other immigrants crowded on the deck of the steamer bound for America.25 In Streisand's defense, one might rebut that Gentiles do not serve as characters in Singer's short story either, and even a mass audience that is presumed to be as ignorant of the past as Allan Bloom claimed might be expected to realize that the United States is a nation of immigrants-some of whom fled persecution as well as poverty. In fact it is to the credit of Yentl to show the internal completeness of Judaic cultural and religious life, to suggest that so singular an ambience did not need to define itself under the pressure of a host society. That nowhere is the word 'Jew" mentioned-an omission shared, incidentally, by such texts as the Book of Genesis and the fiction of Kafka-is a sign of the classiness of Yentl, which is so thoroughlyJewish in its subject matter and spirit that it is vaguely un-American. Like "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," this film barely hints at an external world that serves as a source of fear or of allure. A plausible relocation of such an ambience in the United States would have presented a challenge, a satisfactory standard of representativeness even more so. Set in the same era, Hester Street addresses the varieties of immigrant adjustment to the New World (or at least to New York City); Enemies, A Love Story, based on Singer's 1972 novel, measures the ordeal of Holocaust survivors, whose struggles are hardly indigenous to the overwhelming majority of U.S.Jewry. A film that focuses so intently on the texture of communal life is probably is not easily set in America, from which Haym Solomon had written a letter to his family in Posen that, despite the advantages of economic opportu- nity, there was "wenig Yiddishkeit."26

In its indifference to the larger society, Yentl therefore constitutes something of a breakthrough among mainstream U.S. films; perhaps its only antecedent is The Chosen, based on Potok's novel, which depicted a rather marginal community even within the statistically small branch

[166]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

of Orthodox AmericanJewry in the 1940s. Only around three decades later, Joel Rosenberg has claimed, did it

become possible to show something more like Jewish experience rather than simply images of Jews. This is not to suggest that the category 'Jewish experience" is irrelevant to the intervening eras. Often it is there by its absence: silence, disguise, implicitJewishness, allegorization, sentimental- ization, the soft focus of Gentile actors inJewish roles-all such evasions of Jewish realities are likewise part of Jewish experience, even when it is the larger society that has dictated or encouraged the evasion.27

Another way of suggesting the singularity of Yentl is to note the utter absence of what has been the most typical theme in American movies about Jews: intermarriage. Even several films in which Streisand has starred (from The Way We Were to A Star is Born to The Prince of Tides) highlight such relationships. Even in Enemies, A Love Story, Herman Broder has married the Polish Catholic who has converted toJudaism (a bit uncertainly) after protecting him from the Nazis. In Yentlthe impedi- ments to true romance are not the eerily artificial barriers between Jew and Gentile but rather the tragicomic dilemma that both Avigdor and Hadass happen to "love" a study partner and a groom who is praised for having no secrets to hide. This particular triangle is entirely internal to the Jewish community.

Singer's tale was published near the end of the pre-feminist epoch, a year before Betty Friedan unleashed The Feminine Mystique. To read his story as a similar plea would be anachronistic; that cause was only beginning to regain the momentum lost earlier in the century. But in the early 1960s, a protagonist who has to practice to be a boy in order to be a better practicing Jew was baffling. That may be why Orville Prescott, reviewing Short Friday in the New York Times, was not gentle toward "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," since a tale "about a girl with a man's mind or soul... comes perilously close to being silly." Not long thereafter such a story would be perfectly intelligible; the cultural moment precluded a reviewer like Prescott from appreciating an anomaly like gender-bend- ing: "Even as artful a writer as Mr. Singer can't maintain a uniformly high standard in sixteen stories," and 'Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" demonstrated that he "is an uneven writer as well as a greatly gifted one."28

The author himself later insisted that Yentl's commitment was not to feminism but to learning itself. But the text yields evidence of grievances rooted in sexist discrimination, even though such a vocabulary was not available. When Yentl exposes herself to Avigdor to prove that she is not "Anshel," she explains: "I didn't want to waste my life on a baking shovel

[167]

StephenJ. Whitfield

Yentl

-

and a kneading trough." She later exculpates herself as follows: "I wasn't created for plucking feathers and chattering with females," even if the brazenness of her duplicity might mean losing her share in the world to come. When he wonders why she did not simply marry him, Yentl replies: "I wanted to study the Gemara and Commentaries with you, not darn your socks!"29 Even if Singer's disclaimer of a feminist orientation were accepted, to require that Streisand be faithful to Singer's own under- standing would be reductive and would short-circuit the exploration of his text. The film offered a chance to provide fresh interpretive strate- gies, to make new artistic choices, to retell the story in a way that is alert to the historic limitations imposed upon women and that presents such subjugation as "natural."

Although egalitarianism and studiousness are obviously distinct and separable categories, they cannot be disentangled when it is women who invoke the same right to discuss holy writings that men enjoy. Normative Judaism exhibited its patriarchal character by granting to men a virtual monopoly over learning, which is why-whatever Singer's own interpre- tive assertions-Streisand's feminist version hardly appears strained or ahistorical. The critique now seems incontestable that historic Judaism has been systematically misogynist. Judith Plaskow argues in a represen- tative statement:

Like women in many cultures,Jewish women have been projected as Other. Named by a male community that perceives itself as normative, women are part of theJewish tradition without its sources and structures reflecting our experience. Women are Jews, but we do not define Jewishness. We live, work, and struggle, but our experiences are not recorded, and what is recorded formulates our experience in male terms. The central categories of Torah, Israel, and God are all constructed from male perspectives.30

The domesticity that was assigned to women (and from which some yearned to be emancipated) was their destiny-even when they also had to earn a living, like the widow Peshe who is Avigdor's first wife. A sharp division of labor was fortified by folk wisdom in the era when Yentl "lived"; when Tevye tries to rebut the arguments of his headstrong daughter Chava, he cites "an old custom" that "when a hen begins to crow like a rooster," it is time for the shohet. The father of Emma Goldman, her 1931 autobiography reports, once threw her French grammar into the fire and shouted at her: "Girls do not have to learn much! All aJewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare gefillte fish, cut noodles fine, and give the man plenty of children."31

Such attitudes were hardly confined to AshkenazicJewry. The Tuni-

[168]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

sian-born Gisele Halimi, who became an activist in the French feminist movement, recalled her maternal grandfather telling her-when she was about 10 years old-that women could not lay tefillin. Their role was not to pray but rather to serve the men who pray. When asked what the female role is, her grandfather looked toward the kitchen, into which his wife had disappeared, and said: "A saintly woman, but she does not pray." Halimi later wondered why the morning prayer should not be changed from "Blessed be the eternal one, who did not make me a woman," to sanctify a diversity of hopes and ambitions: "Blessed be the eternal one, who made me as he wished." Or take note of a wry variation-"I always did thank God I wasn't born a woman," which was uttered by the otherwise secular Gertrude Stein, whom Spanish villagers once mistook for a bishop (itself the sort of occupation that requires cross-dressing).32 In the past two decades, Orthodox men have nevertheless felt obliged (to borrow a political slogan) to listen to women for a change, in the United States-where egalitarian claims and the fine-tuning of rights have proven irresistible, where feminism could not simply be met by "zero tolerance." As one historian of American Orthodoxy has noted, "a few rabbis have placed their imprimatur upon separate women's tefilot (prayer services) within their communities," which inevitably provoked a revelatory stridency in defense of halakhah (or, depending on your point of view, of male supremacy). In 1982 the Agudat ha-rabanim dismissed such ceremonies as "worthless":

We are shocked to hear that "rabbis" have promoted such an undertaking which results in the desecration of God and his Torah. We forewarn all those who assist such "Minyonim" that we will take the strictest measures to prevent such "prayers," which are a product of pure ignorance and illit- eracy. We admonish these "Orthodox rabbis": Do not make a comedy out of Torah.33

Without a sisterhood to sustain her, Yentl instead assumed the guise of a young man. To so radical a transformation, Deuteronomy 22:5 posed a formidable barrier, however: "A woman must not put on man's apparel ... for whoever does these things is abhorrent to the Lord your God." The divinely ordained dress code thus forbids transvestism,34 and Maimonides prescribed whipping for those who cross-dress. But he also held that women who study the Torah (as women) were praiseworthy, though admittedly his Mishnah Torah (Hilkhot Talmud Torah 1:13) generalized that "most women are not equipped to study and will distort the words of the Torah according to the whims of their minds."35 But what of fathers wanting to teach daughters who were astute? Sometimes

[169]

StephenJ. Whitfield

Yen Yenti

-

Heaven made mistakes. In eleventh-century Troyes, for example, Rashi had only daughters, and their sagacity and knowledge enabled them to proffer opinions that some rabbis accepted as authoritative. There were female teachers as well as pupils among the Jews of Muslim Spain. Gender separation itself sometimes had to bend, and the "exceptional" features of some women (notably daughters and wives and even grand- daughters of rabbis) were acknowledged. To be sure, a tautology clung to such flexibility. According to some rabbis, the mark of exceptional women was precisely their eagerness to study, and those who managed to achieve mastery of the Bible and of the Talmud were treated, sociologist Sylvia Barack Fishman writes, "with great admiration and respect by the rabbis and scholars in their communities." In the course of the eight centuries after Rashi, many communities harbored some women who became prodigies of learning, and even the late Menachem Mendel Schneerson argued for female study of the Talmud to enhance the transmission of tradition. Many precedents to the contrary notwith- standing, the Lubavitcher Rebbe insisted that not just exceptional women were competent to grasp the oral law. Indeed the entire Talmud could be taught to them, including the knottier passages; those "fine, dialectical" legal brain-teasers were as accessible to the intelligence of wives as of husbands.3

But Yentl was no one's wife (though she was briefly someone's husband), and the deception-which also ran the further risk of self- deception-makes the short story open to interpretive possibilities that were only dimly available to its first readers. Sometimes referring to Yentl as Anshel, oscillating between using the masculine and the feminine pronouns, Singer invited questions about what is normal and what is natural; his tale provokes conjecture on what is timeless and assumed about the social conventions that are associated with gender. The story and the film can be lifted out of the dimensions of "local color" or of Jewish particularism and re-inserted on a very different-and disturb- ing-plane of meaning. Transvestism, the Shakespearean scholar Mar- jorie Garber has argued, "is a space ofpossibility structuring and confounding culture: the disruptive element that intervenes, notjust a category crisis of male and female, but the crisis of category itself." The presence of Yentl thus implicitly defies the binarism that is integral toJudaism, that divides sacred from profane, kosher from unfit, the Sabbath from the rest of the week, and-ineluctably-Jew from Gentile. Yentl is ensnared in the mystery of what a category is and what function it serves, and as Anshel she challenges the viability of the distinctions upon which particular cultures-if not culture itself-are founded. The mystery cannot be entirely dispelled; Yentl lingers even when she is subtracted

[170]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

from the equation that will bind Avigdor and Hadass under the hupah (in ajoyless ceremony at the end of Singer's tale). Because the protago- nist is "a figure of ambivalence, complex subjectivity, and erotic power" who attracts both a man and a woman, both the fiction and the film put at the center, Garber writes, "the transferential object of desire."37

From that angle, however, Singer's Yentl is a more disturbing and ambiguous character than Streisand's. Hers is not masculine at all-no down on the lip, no bony features, no doubts about her own gender. A firm sense of her female self is never surrendered. She remains a woman pretending to be a man, and is therefore far more like, say, theJosephine (Tony Curtis) of Some Like It Hot than Geraldine (Jack Lemmon), who cavorts so convincingly as a female that the boundary from Jerry has been crossed. But in Singer's fiction Yentl dreams that "she had been at the same time a man and a woman, wearing both a woman's bodice and a man's fringed garment." (Never mind for the moment that, among her Gentile neighbors and theirJewish imitators, a fringed garment was far more likely to be a woman's than a man's.) "Only now," Singer contin- ues, "did Yentl grasp the meaning of the Torah's prohibition against wearing the clothes of the other sex. By doing so one deceived not only others but also oneself."

Singer makes Anshel the name of a deceased uncle. Streisand's version gets closer to the enigmas of intimacy and of identity by making Anshel the name of a deceased brother and thus more hauntingly the marker of her male alternative. Although skill at chess is not an acquired characteristic that can be genetically transmitted, Avigdor is introduced to the movie audience playing the game; Yentl's father had been a chess player too. In both the story and the film, Anshel substitutes herself for Avigdor in seeking to marry Hadass, and he in turn bonds so closely with Anshel that the model of David and Jonathan is mentioned.38 Yentl is condemned to love not only learning but also (like Viola in Twelfth Night) a boy who thinks that she is a boy. The control of passions, which is the Talmudic definition of strength quoted in the father-daughter dialogue early in the film, will not be respected; Yentl is no better at exhibiting that sort of power than in the arm-wrestling contest when she meets Avigdor. "No greatwork of the imagination has ever been based on illicit passion," Charles Eliot Norton once foolishly proclaimed,39 forgetting all about Tristan and Isolde, Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary and The Scarlet Letter. What befalls Yentl is yet another violation of that dictum and another vindication of the unsettling properties of art.

A final defense of Yentl can be advanced in terms of Streisand's own importance to AmericanJewish culture. The theme of the first film that she directed-a fable of female emancipation from the shackles of

[171]

StephenJ. Whitfield

Yentl

-

convention-may be at least as apposite a self-reflexive work as the first film in which she starred, because the show-business saga of Fanny Brice was played out within a different frame of reference. Funny Girl por- trayed a vaudeville and musical comedy star who lacked Streisand's ethnic self-assurance (and who, incidentally, did not speak Yiddish). Although Brice was enormously popular, she wanted to attract an even larger audience, one that might be turned off by a performer who was "too New York" and "too Jewish." She had changed her name from Borach, but she was hardly alone in an era when those who wanted to see their names in lights rarely kept their own. How far would Isaiah Edwin Leopold have gone had the comedian not erased his first and last names and split his middle name into Ed Wynn? And, later, how at home on the range would Kirk Douglas have seemed had he been billed as Issur Danielovitch? Nor is self-hatred a plausible explanation for the actor Laurence Harvey's decision to drop the name first bestowed in Lithua- nia (Laruska Mischa Skikne), or for the producer Mike Todd to switch from Avrom Girsch Goldbogen. And would there have been marquees big enough to bill Walter Matthau, whose career began in the Yiddish theater, had he insisted on keeping the surname of Matuschanskayasky? Until roughly the 1960s, show business (like national politics) was often designed to disguise the multi-ethnic mosaic that is the United States.

But Fanny Brice went further: she altered her unmistakably ethnic appearance. Even as power was being transferred from the late Warren Harding to Vice President Calvin Coolidge in August 1923, the news of her nose job was jostling for space in the New York Times. "Everything about me has stopped growing except my nose," Bricejoked, even as she sought to be cast in serious dramas instead of musical comedies. Surgery would eliminate the stigma of being "tooJewish," though she could not publicly acknowledge the truthfulness of the quip attributed to Dorothy Parker that Brice had "cut off her nose to spite her race." Sadly she failed to get the serious parts she craved and to grow as a dramatic actress. Directors and audiences seemed to want her as she had been, and they continued to type-cast her as a clown rather than elevate her into a tragedienne. Even her marriage suffered. When divorce papers were filed four years later, she charged that the surgery had alienated the affections of Nicky Arnstein, heightening his sense of inferiority in the presence of his gifted and famous wife: "I was not the same Fanny he used to know."40

The contrast with Streisand need not be belabored. Her consistent refusal to consider ethnicity a birth defect or a bad career move is a striking index of the legitimation of diversity in the evolution of Ameri- can popular culture. "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy" would never have been

[172]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

transferred to the screen were her identity as a Jew (and her commit- ment to feminism) of superficial importance to her. It seems weirdly appropriate that, to promote Yentl, Streisand's first appearance was in New York at the annual dinner of UnitedJewish Appeal, which named her the UJA's Man of the Year. With her feistiness as much as her less- than-classic profile, and with a reputation for pushiness that doubled for her status as Jew and as woman, she reminded no one of Miss America (not even of Bess Myerson).41 The making of Yentl is therefore a tribute to one artist's tenacity, which was tested for so long that almost half of Streisand's entire career in Hollywood was spanned.

The result reveals as well as any other such American artifact the conflict between the subtleties of high art and the appeal to the masses, between elitism and vulgarization, between the original, personal vision of a writer and a personal signature in a collective enterprise. Such a clash is hardly unique to the United States, but it is especially acute where the operations of the democratic marketplace are so largely uncontested. Consider the first "talkie," which happened to be about Jews and was also a musical in which the star was (almost) the only performer permitted to sing. In 1927 the jazz singer must choose between succeeding his father in shul and succeeding in mass entertain- ment. Yet in Max Nosseck'sYiddish film, Overture to Glory (1940), another cantor's son, Moishe Oysher, abandons the synagogue to perform in the Warsaw opera, which is hardly the equivalent of Al Jolson's Winter Garden. The United States would soon allow tenors likeJan Peerce and Richard Tucker to chant in shul andto sing at the Met. But show-business values remained virtually idiomatic, and the plea to let the people decide is an aesthetic criterion as well as a political one. George Gershwin's operatic experiment with Porgy and Bess aroused such suspicion among the Hollywood executives who valued his creative services that in 1936 he fired off the following telegram: "Rumors about highbrow music ridicu- lous. Stop. Am out to write hits."42 The rumors stopped because the hits got written-and even Gershwin had abandoned plans to base an opera on TheDybbuk so that he could explore Catfish Row. The story of Yentlhas cultural reverberations because it comes with a question: how much of a compromise must be made for the sake of addressing the masses, which would have found references to hallah and Sukkot and kaddish quite foreign, and which would have been unable to locate Zamosc or Lublin on a map?

A properly nuanced recounting of this history would acknowledge that Singer himself had no principled objections to popular satisfaction; he claimed to reject the turn in Yiddish theater toward "plays that don't entertain. They write plays for the feinschmeckers, for the elite, for people

[173]

Stephen. Whitfield

Yentl

-

who like allusions toJoyce and Kafka. When I go to the theater I want to see a love story with humor and a little joy, not to convince myself how erudite I am." He added: "A theater is not made so you can sit there and recognize a passage from Joyce. A theater is made to entertain. No entertainment-no theater!" The wide readership that Singer's books have enjoyed at home and abroad (in further translations) has also shown how exoteric his own art is, how compatible it is with popular appreciation. One must nevertheless deem it probable (and probably gnawing) that Barbra Streisand gave Isaac Bashevis Singer a bigger audience than his own writings ever did. The cost was to tag Yentl's story more with her own name than with his.43

When Streisand unbuttons her shirt to show herself as Yentl, she pleads with Avigdor to accept who she really is. "There's no book with this in it," she asserts. That line is a declaration of independence, stating that Yentl itself would not be joined at the hip with Short Friday and Other Stories, that film should not be judged only by its fidelity to a text. Indeed, despite the intense bookishness of the East EuropeanJewish culture that Streisand's movie celebrates, the medium she uses does prove apt in portraying the fate of Yentl-and merits appreciation on its own terms, removed from the shadow of Singer's original creation. "There's no book with this in it" is a monosyllabic announcement that novelties should not be sought only in novels and short stories, and that the future need not be foreclosed in the sefer ha-hayim (the book of life). The belief that history itself is something still to be written constitutes a supremely American contribution toJewish culture.

Notes

I very much appreciate the help of Donald Altschiller, Jeffrey S. Gurock, Matthew Nesvisky, David B. Starr, and especially Felicia Herman in the preparation of this essay.

1 Isaac Bashevis Singer, "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," trans. Marion Magid and Elizabeth Pollet, in The Collected Stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer (New York, 1982), 149.

2 Quoted in Michael Shnayerson, "A Star Is Reborn," Vanity Fair 57 (November 1994): 193.

3 Moses Hess, Rome andJerusalem: A Study in Jewish Nationality, trans. Meyer Waxman (New York, 1945), 52.

4 Tom Tugend, "Streisand's Big Risk," Jerusalem Post, December 9, 1983, p. 14; Felicia Herman, "The Way She Really Is: Images of Jews and Women in the Films of

[174]

Jewish Social

Studies

-

Barbra Streisand," in Talking Back: Images ofJewish Women in American Jewish Popular Culture, Joyce Antler, ed. (Hanover, N.H., 1998), 184;James Spada, Streisand: Her Life (New York, 1995), 402, 403.

5 Quoted in Spada, Streisand, 401, 404, 405.

6 Ibid., 403, 405-6; Stephen Holden, "How a Star Is Born, and Grows Up," New York Times, September 22, 1991, sec. 2, pp. 28,32.

7 Quoted in Spada, Streisand, 407; Chaim Potok, "Barbra Streisand and Chaim Potok," Esquire 98 (1982): 117-18, 120-21,124, 126-27; Shnayerson, "A Star Is Reborn," 159.

8 Quoted in Janet Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer: A Life (New York, 1997), 198, 199; Spada, Streisand, 406,408,409-10, 416, 417.

9 Quoted in Stephen Holden, "Barbra Streisand: Don't Get Me Wrong," New York Times, Decem- ber 22, 1991, sec. 2, p. 9; Pauline Kael, For Keeps (New York, 1994), 1015; Spada, Streisand, 417-18, 419; "I. B. Singer Talks to I. B. Singer About the Movie 'Yentl,"' New York Times, January 29, 1984, sec. 2, p. 1.

10 "I. B. Singer Talks to I. B. Singer," 1; Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer, 199-200.

11 SaulJ. Berman, "Kol Isha," in RabbiJoseph Lookstein Memorial Volume, Leo Landsman, ed. (New York, 1980), 45-66; Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer, 200-201; Douglas Feiden, "Charedi Seeking to Ban Barbra at Peace Rally," Forward, December 1, 1995, p. 1.

12 Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer, 201;

Singer, 'Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," 159-60.

13 RichardJ. Israel, The Kosher Pig and Other Curiosities of Modern Jewish Life (Los Angeles, 1993), 6, 8, 9-10.

14 Singer, "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," 169; Marjorie Garber, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety (New York, 1992), 83.

15 Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance (New York, 1934), 147; "I. B. Singer Talks to I. B. Singer," 1.

16 Quoted in Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer, 198, 199; Kael, For Keeps, 1018.

17 Joel Rosenberg, 'Jewish Experi- ence on Film: An American Overview," American Jewish Year Book 96 (1996): 11.

18 Alfred Kazin, A Walker in the City (NewYork, 1951), 60; Garber, Vested Interests, 79.

19 Quoted in Pamela S. Nadell, "'Top Down' or 'Bottom Up': Two Movements for Women's Ordination," in An Inventory of Promises: Essays on American Jewish History in Honor of Moses Rischin, Jeffrey S. Gurock and Marc Lee Raphael, eds. (Brooklyn, 1995), 198-202.

20 Jonathan D. Sarna, A Great Awakening: The Transformation That Shaped Twentieth-Century

Judaism and Its Implications for Today (NewYork, 1995), 19, 22-24.

21 Quoted in Dwight Macdonald, "No Art and No Box Office" (1959), in Discriminations: Essays and Afterthoughts, 1938-1974 (NewYork, 1974), 254; also quoted in Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer, 198, and in Tugend, "Streisand's Big Risk," 14.

[175]

Stephen. Whitfield

Yentl

-

22 J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (Boston, 1951), 136; Brian Boyd, Nabokov: The American Years (London, 1993), 466; Graham Greene, "The Novelist and the Cinema-A Personal Experi- ence" (1958), in The Graham Greene Film Reader: Reviews, Essays, Interviews and Film Stories, David Parkinson, ed. (New York, 1995), 443, 445.

23 Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York, 1987), 64.

24 David Roskies, interview with Allen Hoffman in "Men of Faith," The Pakn Treger24 (1997): 40; Herman, "The Way She Really Is," 185, 186-87.

25 Herman, "The Way She Really Is," 187.

26 Quoted in Arthur Hertzberg, "United StatesJewry-A Look Forward," in The American Jewish Experience, 2nd ed.,Jonathan D. Sarna, ed. (NewYork, 1997), 351.

27 Rosenberg, "Jewish Experience on Film," 27.

28 Orville Prescott, "Demons, Devils, and Others," New York Times, December 14, 1964, p. 33.

29 "I. B. Singer Talks to I. B. Singer," 1; Singer, "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," 164, 165.

30 Judith Plaskow, StandingAgain at Sinai:Judaism from a Feminist Perspective (San Francisco, 1990), 3.

31 "Chava," in The Best of Sholom Aleichem, Irving Howe and Ruth R. Wisse, eds. (Washington, D.C., 1979), 169; Emma Goldman, Living My Life (New York, 1970), 1:12.

32 Gisele Halimi, Le lait de l'oranger (Paris, 1988), 26; Malcolm

Bradbury, Dangerous Pilgrimages: Trans-Atlantic Mythologies and the Novel (London, 1995), 256, 318.

33 Quoted in Jeffrey S. Gurock, American Jewish Orthodoxy in Historical Perspective (Hoboken, NJ., 1996), 60-61.

34 Garber, Vested Interests, 28-29. 35 Quoted in Sylvia Barack Fishman,

A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community (New York, 1993), 184.

36 Ibid., 184, 186-88, 193; Raphael Patai, TheJewish Mind (Detroit, 1996), 102.

37 Garber, Vested Interests, 17, 80, 82. 38 Singer, "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy,"

155, 160; Garber, Vested Interests, 78,82.

39 Quoted in Alfred Kazin, On Native Grounds: An Interpretation of Modem American Prose Literature (Garden City, N.Y., 1956), 57.

40 Barbara W. Grossman, Funny Woman: The Life and Times of Fanny Brice (Bloomington, Ind., 1991), 148, 149, 150, 169;Joyce Antler, TheJourney Home:Jewish Women and the American Century (New York, 1997), 149.

41 Garber, Vested Interests, 80; Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Deborah, Golda and Me: Being Female andJewish in America (New York, 1991), 267.

42 Quoted in Deena Rosenberg, Fascinating Rhythm: The Collabora- tion of George and Ira Gershwin (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1997), 321.

43 Isaac B. Singer, "The Yiddish Writer and His Audience," in Creators and Disturbers: Reminis- cences by Jewish Intellectuals of New York, Bernard Rosenberg and Ernest Goldstein, eds. (New York, 1982), 42; Hadda, Isaac Bashevis Singer, 202.

[176]

Jewish Social

Studies

Article Contentsp. [154]p. 155p. 156p. 157p. 158p. 159p. 160p. 161p. 162p. 163p. 164p. 165p. 166p. 167p. 168p. 169p. 170p. 171p. 172p. 173p. 174p. 175p. 176

Issue Table of ContentsJewish Social Studies, New Series, Vol. 5, No. 1/2, American Jewish History and Culture in the Twentieth Century (Autumn, 1998 - Winter, 1999), pp. 1-206Front MatterIntroduction [pp. 1-2]The First Loves of Isaac Rosenfeld [pp. 3-24]In the Wilderness: Reflections on American Jewish Culture [pp. 25-39]Historical Reflections on the Problem of American Jewish Culture [pp. 40-51]The Cult of Synthesis in American Jewish Culture [pp. 52-79]Scholarship as Lamentation: Shalom Spiegel on "The Binding of Isaac" [pp. 80-90]"Harbe sugyes / Puzzling Questions": Yiddish and English Culture in America during the Holocaust [pp. 91-110]"O Taste and See": The Question of Content in American Jewish Poetry [pp. 111-123]Taking Jewish American Popular Culture Seriously: The Yinglish Worlds of Gertrude Berg, Milton Berle, and Mickey Katz [pp. 124-153]Yentl [pp. 154-176]Mitzvah and Medicine: Gender, Assimilation, and the Scientific Defense of "Family Purity" [pp. 177-202]Back Matter [pp. 203-206]