World’s Hottest Blue-Water Destination - edc.uri.edu · to tell me about the experience after...

Transcript of World’s Hottest Blue-Water Destination - edc.uri.edu · to tell me about the experience after...

www.SportFishingMag.comwww.SportFishingMag.com

VOLUME 18 ISSUE 3U.S. $4.99 CAN.

VOLUME 18 ISSUE 3U.S. $4.99 CAN.

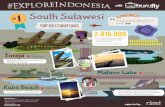

World’s Hottest

Blue-WaterAscension Island

TRY SMALL BAITS FOR BIG FISH OFFSHORETRY SMALL BAITS FOR BIG FISH OFFSHORE

ELECTRONICSAll the Latest and Greatest GearHow to Choose and Use Chart Plotters

ELECTRONICSAll the Latest and Greatest GearHow to Choose and Use Chart Plotters

MARCH 2003

World’s Hottest

Blue-WaterAscension Island

Guide to ChesapeakeOyster Reefs

Guide to ChesapeakeOyster Reefs

Florida’sBehemothBlack Drum

Florida’sBehemothBlack Drum

DestinationDestination

••

••

20032003

Osborne had gone out before work to fish the Monitor-Merrimack Bridge-Tunnel in Hampton Roads, Virginia. On theway back, he stopped at the spot where Norfolk’s Lafayette Rivermeets the larger Elizabeth River. The minute he turned off theengines of his 20-foot cat, he heard the predators chasing silver-sides (also called spearing) as an ebb current swept them throughtiny channels between a series of oyster-shell mounds along achannel edge. Unable to contain his enthusiasm, Osborne calledto tell me about the experience after reaching his office.

The most innovative reef-building program in theChesapeake Bay doesn’t depend on old ships — it’s built onoyster shells. Shells form the bases of more than 50 oyster reefsthat the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) hasbuilt during the past 10 years. The program aims to restore oys-ter brood stock (adult oysters that contribute the most off-spring to the population), but the resulting fish habitat pro-vides a great byproduct for bay anglers.

Bottomfishermen have long been attuned to the feel of

sinkers on shells and the characteristic pattern of flat oysterbars on depth sounders, but it has been a long time — morethan a century — since visible oyster reefs dotted the bay. Thesenew reefs have proven so successful at attracting fish that someof the money for them now comes from the Virginia Salt WaterFishing License Fund, with the enthusiastic support of theCoastal Conservation Association’s Virginia chapter (CCA-VA).

Restoring oysters also should help revitalize theChesapeake’s seafood industry and clean up the bay (a matureoyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day, removingsediment as it feeds on algae).

Oyster HistoryTo the Algonquin Indians, “Chesapeake” meant “great

shellfish bay.” Early accounts by Europeans like Capt. JohnSmith describe huge reefs that made navigation hazardousthroughout the bay. Harvesting oysters meant simply beachinga small boat and picking up shells.

Iheard ’em before I saw ’em!” Kendall Osborne told me excitedly over the phoneone morning last summer. “Schoolie rockfish [striped bass] were busting bait allaround the shell piles. I had a ball with them for half an hour, casting a popperon floating line.”

A few early-morning casts near the LafayetteRiver oyster reef in Norfolk, Virginia, canpay off with speckled trout, rockfish, puppydrum and flounder. With the help of volunteersand federal agencies, Virginia has built morethan 50 such reefs to restore oyster-breedingpopulations in the Chesapeake Bay.

www.SportFishingMag.com MARCH 105

cartons, Wesson says. The reefs sit on naturaloyster bars in 8 to 10 feet of water on theedges of channels. Groups of students andadults organized by Chesapeake BayFoundation staff raised hatchery-bred oystersto stock the reefs, using small floating “oystergardens” as a sort of backyard aquaculture ini-tiative. In addition, VMRC and CBF fundedseveral buyback programs in which watermenharvested mature spawning-stock oysters toplace on the reefs.

The results proved encouraging, even inlight of oyster diseases that have plaguedthe bay since the 1960s. Oysters on the reefsgrew faster than their flat-bar counterparts.Reproductive rates were high enough thatWesson began spreading shell around theperimeters of the reefs to catch the “shad-ow” of spat (baby oysters) from larvae theoysters produced.

More reefs have been built throughoutVirginia’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay sinceWesson and VMRC partnered with the OysterHeritage Program of Virginia’s Department ofEnvironmental Quality. Federal agencies suchas the National Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration and the U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers have thrown their hats into thering as well. There are now four reefs in thePiankatank River, two in the York, three in therivers of Mobjack Bay, two in the James, sevenin the Elizabeth River system (includingKendall Osborne’s favorite), five in theLynnhaven River, one in Pungoteague Creekon the Eastern Shore, two in the GreatWicomico, and several in the Yeocomico andCoan rivers. The Corps of Engineers helpedbuild some of the 10 reefs that theRappahannock now boasts and has recentlycompleted eight reefs in the Tangier andPocomoke sounds.

CBF’s Oyster Corps program to stock thereefs has grown to include 3,000 students atmore than 100 Virginia schools, and morethan 1,400 families. A commercial-scale oys-ter farm operated by CBF supplements theoysters that volunteers produce. The 1 mil-lion CBF oysters at the farm, one of the largestsuch facilities on the East Coast, may be morefortunate than other commercially grownoysters. These mollusks are scheduled forrelease at Virginia reefs.

Multifaceted Fish HabitatYou won’t need a GPS to find these reefs —

just look for the signs that read “Danger,

104 SPORT FISHING www.SportFishingMag.com

After the Civil War, oystermen from NewEngland who had decimated their local stockscame to the Chesapeake with steam vesselsand toothed dredges, inspiring local water-men to copy their techniques. Railway linesfacilitated long-distance shipping of thecatch, and the industry boomed. By the endof the 19th century, the Virginia-Marylandharvest exceeded 15 million bushels per year.Although the supply at first appeared limit-less, harvests quickly outpaced the oysters’capacity to reproduce.

Chesapeake oysters began a long declineearly in the 20th century, but overharvestingcreated only part of the problem. Changesmade to the structure of reefs put further

strain on the shellfish:It’s easier to harvest oys-ters from flat bars thanfrom high mounds, sowatermen scraped reefsflat over time. A flat,low bar, though, forcesoysters to expend ener-gy pumping out sedi-ments instead of grow-ing and reproducing. Ata time when we were

pouring soil into the bay by developing itswatershed, we were unwittingly making itsoysters more vulnerable to the sediment.

Under stress from sediment, oysters fell preyto diseases. Two parasites, MSX and Dermo,decimated stocks in the late 1980s and early’90s. Bay harvests dropped below 100,000bushels, but in recent years they have climbedback toward a few hundred thousand bushels.

New Thinking aboutRestoration

As the Chesapeake’s oyster populationcrashed, scientists, resource managers and

environmentalists began to stress oysters’ecological value as filters and habitatproviders in addition to their value asseafood. Restoration programs aimed atbringing oysters back for all three reasonsevolved in Virginia and Maryland.

VMRC’s Jim Wesson, chief of shellfishconservation and replenishment, startedthinking about an old print he had seen ofNative Americans harvesting oysters from ahigh reef in the 17th century. Wesson, a for-mer waterman who holds a doctorate inwildlife management, reasoned that oystersdepicted in the print had thrived because theelevation kept them away from bottom sedi-ments and put them in a zone of water withhigher levels of dissolved oxygen. Water clos-er to the surface also contains greater concen-trations of algae, which oysters eat.

Wesson began the restoration project in1993 by building two reefs in the PiankatankRiver from mounds of oyster shells purchasedat local shucking houses. The structure of theshells on the bottom mimicked closely thehistoric drawings from observations madecenturies before. When completed, the oys-ter-shell structures measure 100 yards long by10 yards wide. Placed in rows, the moundsform a pattern that looks like inverted egg

25 250

MILES

Tappahannok

Completed oyster reef restoration sites

Ch

esap

eake

Bay

Smith Island

Tangier Island

Potomac River

Rappahannock River

James River

York River

Piankatank River

Mobjack Bay

Great Wicomico River

Tangier Sound

Pocomoke Sound

Lafayette River

Lynnhaven River

Elizabeth River

Pungoteague Creek

Wreck Island

Hog Island

Assateague Island

West Point

Hampton

Norfolk

Fishermans Island

Newport News

Richmond

LEARNMORE, GETINVOLVED

• For more informationabout Virginia’s OysterHeritage reef program, visitwww.deq.state.va.us/oysters/homepage.html.• For information on howyou can participate in theOyster Corps Program, visitthe Chesapeake BayFoundation’s Web site,www.savethebay.cbf.org.• Two good fly-rod/light-tackle guides who know howto fish the VMRC reefs areCapt. Chris Newsome ofGloucester (804-642-1925;[email protected]) andCapt. Kevin duBois ofNorfolk (757-486-6735;www.coastalexplorer.com). • Underwater grass bedsand oyster reefs make anunbeatable combination forattracting fish. If you’reinterested in finding outwhich reefs have grassclose by, visit the Web siteof the Virginia Institute ofMarine Sciences atwww.vims.edu. On the homepage, click on BiologicalResearch Programs, then onBay Grasses (SAV). You’llfind a lot of basic informa-tion on the bay’s grasses,plus quadrangle maps ofgrass distribution in 2001.

The Chesapeake BayFoundation gives these seedoysters to volunteer oyster"gardeners," who raise the little mollusks in floating pensfor later release into the bay.

This splendid striped bass came from watersnear the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Anglershope fish like this will become more commonas projects such as Virginia's oyster-reef development improve water quality and habitat.

Young oyster gardenersrelease adult oysters over areef in the Lafayette Rivernear Norfolk, Virginia.

These two tanks demonstratehow well oysters filter water.Volunteers poured a bucket ofChesapeake Bay water intoboth tanks, then placed adultoysters in the left tank. Within20 minutes, water in the left tank had cleared, whilewater in the right tankremained cloudy.

www.SportFishingMag.com MARCH 107

good tide movement. For speckled trout andbig croakers, try to fish low-light periods earlyand late in the day. In spring and especially infall as the cooler weather chills the water,most reef fish feed through the day. Oyster-reef predators fall for bull minnows (killifish),squid strips, bloodworms and chunks of peel-er crab. Fish these baits on bottom rigs aroundthe deep edges and flats.

Fly-fishermen will find that chartreuse/white Clouser Deep Minnows work well here.Sink-tip or sinking lines allow you to coverdeep edges and flats effectively. A friend tooka speck over 7 pounds this way in thePiankatank two years ago. At high tide, espe-cially under low-light conditions, a Clouserwith small eyes fished on a slow-sinking inter-mediate line remains the fly of choice onshallow flats over shells or grass.

Jigs rank as the all-time favorite lure forfishing the reefs. Try a 4-inch Lunker CityFin-S Fish, Bass Assassin Split Tail Shad, orBerkley Power Grub on a 1/16- to 1/4-ouncejig head and 6- or 8-pound spinning tacklefor light-tackle fun. A white or chartreusebucktail also works well. Tip jigs with achunk of peeler crab or a 2-inch pennant ofsquid to persuade fish to bite on slow days. Iimprove my chances by soaking plastic tailsin menhaden (bunker) oil overnight beforefishing them. (The oil is available in manytackle shops. Put a tablespoon of it into afreezer-weight Ziploc bag with the bodies,and seal tightly.) The D.O.A. TerrorEyz hasalso proven effective on the bay’s game fish.Fishing high tides in the early morning, onesharpshooter on the Piankatank has donewell with poppers and a Rebel Windcheaterdanced along the tops of the reefs.

Anglers throughout Virginia’s tidewaterare only beginning to discover the VMRC oys-ter reefs, so the territory remains fertile forexperimentation. The techniques outlined

here offer a starting point, but the mostimportant part of the game is learning howthe reefs function as fish habitat. Study themcarefully and you may develop the nextbreakthrough technique for fishing them.

Capt. Rob Brumbaugh is the Chesapeake BayFoundation’s Virginia fishery scientist. He tracksfishery management issues in the lower bay as anadvocate for sustainable management programsand oversees oyster restoration programs. TheChesapeake Bay Foundation is the largest private,nonprofit conservation organization working tosave the bay. With more than 100,000 members,CBF operates award-winning programs inresource protection and restoration and in envi-ronmental education.

106 SPORT FISHING www.SportFishingMag.com

Oyster Reef, Keep Off.” Because reefs repre-sent hazards to navigation, large orange-and-white signs clearly mark their locations.Harvesting oysters is strictly forbidden, butthere’s nothing wrong with drifting over (athigh tide) and beside the reefs.

You’ll find that Wesson placed most reefsalong channel edges, with shell spread on thedeep side. Two major packing companies leaseparts of some reefs as private oyster ground,where they actively plant shell. Motivated bycommercial interest, these companies invest inoyster restoration, but those investments paydividends to fish and anglers. The more shellaround a reef, the better.

The flats inside some reefs now supportbeds of eel and widgeon grass, a possibleresult of increased filtration by the nearbyoysters and the wave-dampening effect of the

reefs themselves. In any event, the combina-tion is appealing to fish: shallow flats coveredwith shells or underwater grasses, the three-dimensional inverted-egg-carton reefs, deeperflats with shell bottoms and channel edgeswith plenty of tide movement.

Consider the nature of VMRC reefs. Thesestructures successfully produce oystersbecause they offer great surface area for oysterlarvae to settle and attach. Shells on the reefprovide nooks and crannies that protect spatfrom predators like blue crabs. Likewise, thenooks and crannies offer prime habitat formarine worms, small mud crabs, grassshrimp, amphipods (tiny crustaceans) andsmall fish such as naked gobies. The hardshells make solid attachment points for red-beard sponges, mosslike bryozoans, and bar-nacles. All this live material, plus oyster spatthat settle on the shells’ surfaces, attract crabs.The worms, barnacles and amphipods attractjuvenile spot, white perch, silversides andother little fish.

With all this food (and even greater varietyof habitat if grass beds lie nearby), it’s no won-der that the VMRC reefs have become fishmagnets hosting glamorous residents such as

speckled trout, rockfish and puppy drum(young redfish). Other residents and visitorsinclude croaker, flounder and gray trout. Lookfor puppy drum, especially on the reefs closeto the bay’s mouth, like the ones inLynnhaven. A sporting interloper that Ialways enjoy is the cownosed ray, whichpreys on oysters. Because the ray’s numbershave increased dramatically in recent years,you’ll likely do the reefs a favor by keepingany cownosed rays you catch — if you enjoygrilled ray.

Fishing the ReefsTo fish a VMRC reef effectively, first do

some scouting missions, preferably in a skiffof 20 feet or less. Nose up onto the shell piles,paying attention not only to what you see,like schools of minnows, but also to your fish

finder and depth contours around the piles. Study a chart as well, to see how the reef

lies along the channel edge. Does the reefcurve in or out? Watch how the tide flowsaround any curve and the ends of the reef.Points and curves create eddies that trap bait-fish and give fish ambush points, as KendallOsborne found out that summer morning.

Try to visualize how different fish speciesrelate to the reef. Active predators like specksand stripers usually prowl up-tide ends andeddies. Bottom feeders like puppy drum andcroaker browse along the sides, the loweredges and the shell flats outside the reefs.Flounder lie in ambush on the deeper flats,waiting for baitfish.

You need to figure out how to put a lureor bait into these feeding zones; boat posi-tion will be critical. You may be able to polethe shallow flats inside, and if you have anelectric trolling motor, it will serve you well.The two most basic techniques, though, arefiguring out a good drift along the reef andstealthily dropping a small stern anchor tohold over a spot you want to fish particular-ly thoroughly.

Plan visits to the reefs to coincide with

State agencies and volunteergroups have built oyster reefsat many of the river and creekmouths that line the southernend of the Chesapeake Bay,like this one that attracted anangler drifting along Virginia'seastern shoreline.

No need to scout for GPS numbers to locate oysterreefs: Giant orange-and-white signs mark their presence.Anglers may not harvest oysters, but they may fishbeside and (at high tide) overthe man-made structures.

Croaker, such as this one,along with flounder, gray troutand puppy drum, have becomefrequent visitors to the oysterreefs in the Chesapeake Bay.LE

NN

Y R

UD

OW