Wiley Nautical Navigation e-book

-

Upload

john-wiley-and-sons -

Category

Documents

-

view

233 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Wiley Nautical Navigation e-book

8 Estimated position and the traditional fix 69

8

Before the arrival of GPS back in the 1990s, a navigator maintained a plot by first estimating the position then confirming the estimate with a visual fix. Working with GPS we still estimate. If we don’t, we might plot a GPS fix that’s complete rubbish and never notice. The estimate, however, may well be comparatively relaxed. On passage, with fixes going down on the chart every hour or so, it is often enough to say to oneself, ‘I’ve logged five miles since the last fix and the tide is fair. I’ve been steering along the coast. Because I was there an hour ago, I must be about here now’. Attended to conscientiously, this policy is generally considered adequate to ensure your GPS plot isn’t a nonsense. If the GPS fails however, it won’t be enough, so we must retain the skills to do the job formally.

The same could be said of traditional fixing techniques. These were once meat and drink to skippers, and considerable expertise was developed. Today, we use GPS as our primary tool, but that doesn’t mean we can forget the rest. Understanding the classical methods increases comprehension of what navigation is really about, which in turn helps us to ask the right questions of such sophisticated kit as a modern chart plotter. For these reasons, as well as just plain backup, studying this chapter will pay dividends. We’ll start with the classic estimated position.

The estimated position (EP)In order to work up an EP you need to know first of all where you started from, or your last known position. For this information you will refer to your logbook. Next, you need a DR position on the chart, corrected for leeway, so the first job is to plot a ‘course steered’ line on the chart. Here’s the process:

Plot the course steered from the last known position (corrected for leeway, if any). Give it the conventional single arrowhead to show what it is. (A)

Consult the Tidal Stream Atlas or the nearest tidal diamond to see what the tide has been up to. It’s helpful to try and arrange to plot your EPs to coincide with turning over a page in the atlas, because that ensures a convenient one-hour tide to plot.

8 Estimated position and the traditional fix

70 Inshore Navigation

8

Place your protractor at the DR position and draw a Tide Line (three arrow-heads) in the same direction as the relevant arrow in the Tidal Stream Atlas. If your EP is for a whole hour, the length of line will be the number of miles that corresponds to your best estimate of the tidal stream in knots. Should it be less than an hour, make a pro rata adjustment. (B)

At the end of the tide line, draw a small equilateral triangle, point-up. That is your EP. Write the time against it. (C)

Make a logbook entry with the time and the distance-log reading, with a remark such as ‘EP on chart’. If you fail to log the EP, you may as well not have bothered to plot it at all.

Plotting an EP should take seconds, rather than minutes. If you note the time of high water at the required standard port before beginning the passage, and decide if today’s tides are springs, neaps or half-way, you will save a great deal of book-worming. Pencilling in the hours of your particular tide on the pages of the atlas can be a major help (see Chapter 13 – ‘Passage planning’).

You should not expect phenomenal accuracy from an EP. The name does not imply it, and you probably won’t get it. There are too many unknown variables. The tidal information you have is only a prediction. Wind and weather may, and often do, affect the activity of the tides. Your steering compass might not be perfectly accurate. (Where did you leave that screwdriver? – see

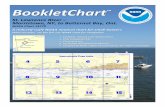

A classic estimated position.

8 Estimated position and the traditional fix 71

8

Chapter 2). With the best will in the world, the helmsman could be misleading you about the course steered, your log is probably somewhat less than 100% accurate and leeway is often little more than an educated guess.

If an EP is all you have in the way of a position, cherish it, but treat it with circumspection. Usually, however, there are ways of checking up on it. The most important way is with a fix.

Fixing your positionThe first action to confirm an estimated position is to take a good look around. This is good practice even if the GPS is still working, because in the end the rocks are real. They’re out there, not on the chart table. Besides, you might see a ship bearing down on you that too much navigation below decks could have caused you to miss. You may find that some buoy which your EP suggested was nearly a mile away is really only a cable off. You could even be about to hit it, which is the best fix in the world, although not one that anyone would really want.

If, in fact, you are close by an easily recognisable object, refer to the chart and see if it ties in with your EP. If everything adds up, look no further. Log the position and enjoy the sailing until next time.

If the boat isn’t close enough to anything to consider your position fixed, you must deduce where you are by using position lines (PLs).

A PL is a line drawn on the chart in an observed direction from a known object. A typical PL is the compass bearing of a lighthouse or beacon. If, using the hand-bearing compass, you take the bearing of a visible object which is recognisable on the chart (the unlit tower on Selsey Bill – PL ‘A’ in the illustration), you are somewhere on a line plotted along that bearing. What

The cocked hat.

72 Inshore Navigation

8

you don’t know yet is whereabouts on the line you are. In order to decide this you must find another PL (in this case a compass bearing on the church spire ‘B’) and plot that too. Since you are somewhere on this PL as well as the first one, it follows that your position is at the point where the two lines of intersect.

If you can produce only two PLs, that’s the job done. Sketch a neat circle around the intersection, label it with the time, and log it as a fix. In the illustration the lighter lines leading from the tower and the church towards the heavy PLs are only there to clarify the issue for learning purposes. In practice, they should only be as long as they need to be to show the intersection, otherwise the chart rapidly begins to resemble the web of a non-union spider.

The three-point fixIt isn’t going to take much of an error in PL ‘A’ or ‘B’ to place you a surprising distance from where you think you are. The classic counter for this possibility is the three-point fix. If a third PL can be added to the two-line fix, it supplies an immediate check on its accuracy. Here, the yellow buoy marking the obstruction is chosen for line ‘C’.

When the three lines coincide, or nearly so, then you have what is probably an accurate fix. Even so, you should still be cautious. Who knows? Maybe for once the errors added up in your favour.

If the lines do not coincide they will form what, for obvious reasons, is known as a cocked hat. The size and shape of your cocked hat gives a good indication of the area of position in which your fix has placed you. The one illustrated is typical and an experienced navigator would be reasonably content with it.

Obviously one or more of the lines is not quite accurate (or wildly adrift) if the cocked hat is very large. You do not know which one, so the safest thing to do, if you have time and you don’t like the size of your cocked hat, is to try again and see if you do any better. If the sea is rough it is quite likely that you won’t improve on your first effort. In this case you must log the fix as it is, but always assume the worst. If part of your area of position lies closer than the rest to a danger, then proceed on the assumption that this is where you are.

Sometimes a fourth PL will help to clarify the situation by crossing neatly with two of the others, thus pointing the finger of suspicion at the third. You then have an idea of which of your PLs to check up on. Don’t just throw the rogue out, however, in case the fourth PL wasn’t any good either.

Which order?Because a fix is going to have a time and a log reading attached to it, the final result should stack up with these as best it can. It’s logical that any position line abeam of you will be changing bearing a lot quicker than one that is dead ahead. Indeed, the one on the bow may not alter so much as a degree in the time it takes you to observe and plot the others. Always start off with the object whose bearing is changing slowest. Move at the end to the one which is racking up the degrees as you sail past it. Check your watch and log reading immediately after the final bearing and the whole thing will tie together neatly.

145

Deduced Reckoning and Estimated Position Appendix A

Deduced Reckoning and Estimated PositionDR Navigation

Estimated Position

Leeway

Error in EP

EP with Multiple Headings

W hen aids to navigation are in short supply, due to equipment failure or lack of any aids, the navigator must resort to traditional methods of navigation.

146

DR NavigationDR navigation is the method of deducing your position using only heading steered and distance run. This is ‘deduced navigation’ and is often known, erroneously in my opinion, as ‘dead reckoning’ rather than ‘ded. reckoning’, but anyway it’s commonly called ‘DR’.

If you know where you started from, the direction in which the boat has been travelling and the distance travelled, it’s very easy to plot where you are on a chart. This makes no allowance for tide or wind, so is only of use in relatively calm conditions where there is little or no tide.

The course steered must be converted from a Compass course to a True course by applying deviation and variation. The distance run is taken from the speed log, which should have been calibrated. If it under reads, you would have travelled further than you thought and may be standing into danger.

Estimated PositionThe estimated position (EP) is determined by applying any tidal and wind effects to the DR position. We’ll look fi rst at applying only tide.

We will need to establish in what direction and at what speed the tide has been pushing the boat for the time since we last knew our position. This is obtained from the tidal atlas. If, for instance, the last ‘fi x’ was 1 hour ago, we will need to examine the tidal

Deduced Reckoning and Estimated Position Appendix A

147

atlas page for that particular hour. As we will be transferring the direction using our plotter, we need only ‘line it up’, without actually reading the direction. We will, however, need to determine its speed by noting if the day’s tidal range is neaps, springs or in between.

Now we will mark the direction of the tidal fl ow on the chart, using the plotter. Then we can mark the distance the tide will have carried us since the last fi x. The symbol for an EP is a triangle, to distinguish it from a fi x.

The resulting position is our estimated position. We must mark on the chart the total distance run and the time of the EP, so that anyone looking at the chart will have all the information they need at a glance.

If we are interested in where the boat had actually travelled over the ground since the last fi x, then all we have to do is join the fi x position to the EP. This is the average track that we have made good, though because it has used the average tide for the period, it won’t represent the true picture exactly.

148

LeewayWind can blow the boat sideways through the water. Boats will be affected in different ways according to their shape, both above and below the water, the direction and strength of the wind, the boat’s speed and the direction of the wind relative to the boat. It’s normal to allow for 0 degrees, 5 degrees or 10 degrees according to conditions. Leeway can be estimated by measuring the direction of the wake of the boat with a hand-bearing compass and comparing it with the boat’s heading. The boat will be blown ‘down wind’ from the boats heading. It’s a good idea to always sketch a wind arrow on your chart so that you apply leeway in the correct direction.

Error in EPBecause an EP relies on information that may not be as accurate as we would like, it’s normal to allow for an error of up to 10% of the distance run when working out our next course. Draw a circle of radius 10% of distance run since the last reliable fi x centred on the EP. Assume that your position is in a position, within the circle, nearest to danger. In other words ‘navigate the circle’ rather than the boat.

EP with Multiple HeadingsYou don’t need to work out an EP at each change of heading. Provided that you note the log distance at each change of heading, you can run a series of DR positions and insert the tide or tides at the end when you are ready.

This will not give you an indication of the ensuing ground track but give a good EP.

Standard SymbolsWe must use the standard symbols for our chart work so that any other person will understand what we have plotted.

The course through the water has one arrow.The course over the ground has two arrows.The tide has three arrows.

•

•

•

Learn the NauticalRULES OF THE ROADThe Essential Guide to the COLREGs Paul Boissier

For yachtsmen and professional marinersAccess to free on-line testsIdeal for exam preparation

With foreword bySir Robin Knox-Johnston

50p from saledonated to RNLI

How to Recognise other Vessels by their Lights and Shapes: Rules 20–31 and 36 19

3

3 How to Recognise other Vessels by their Lights and Shapes: Rules 20–31 and 36

Read through Rules 20–31 and 36 before you start on this chapter.

Vessels carry lights and shapes for two purposes:

1 To establish the presence and orientation of the ship, and whether it is under way and making way. This is done with side, stern and masthead lights which I will refer to as navigation lights.

2 To establish how manoeuvrable a ship is in comparison to others. This is done with supplementary lights and shapes that I will refer to as identification lights and shapes.

The Rules assume that power-driven vessels have complete freedom of movement (unless they are Not Under Command (NUC); Restricted in their Ability to Manoeuvre (RAM), and so on). Every other vessel is, by implication, constrained to a greater or lesser extent in its ability to avoid a collision. We will come to the Manoeuvring Rules in Chapter 5, and we will see that Rule 18 establishes a ‘hierarchy’ that requires more manoeuvrable vessels to keep out of the way of those that are less manoeuvrable. For this to work, the ships that are less manoeuvrable must make sure that they clearly signal their limitations – by lights, shapes and sound signals.

Unencumbered power-driven vessels do not carry identification lights or shapes, but any vessel with a manoeuvring limitation does.

If possible, you should always check the other vessel’s lights and shapes before deciding on any avoiding action, in order to determine its orientation and where it stands on the manoeuvring hierarchy.

In daylight and good visibility, it is relatively easy to identify another vessel by eye, and to calculate its approximate range and orientation. A fishing boat is pretty much unmistakable, for instance, as is a dredger. But a vessel’s manoeuvrability is often less easy to work out, and that’s what the shapes are for. For instance:

Are those two merchant vessels following closely behind each other doing so by chance – or ■

is one towing the other?

Is that sailing vessel using its engine for propulsion, or is it just sailing? ■

ch03.indd 19 3/10/10 3:29:40 PM

20 Learn the Nautical Rules of the Road

3

What about that container ship coming up the narrow channel – is it free to manoeuvre, or is ■

it constrained by its draught?

At night, or in restricted visibility, just about every vessel will show sidelights and a sternlight. In addition, the majority will show one or two masthead lights. These lights, taken as a whole, are invaluable; to an experienced eye, they will tell you what sort of ship it is, together with its range and orientation and likely size.1 But they won’t tell you how manoeuvrable it is. For this, you need to check for any identification lights, which may or may not be displayed with side, stern or masthead lights, depending on the circumstances.

When Lights and Shapes Must be Used (Rule 20)

Lights are to be shown on three specific occasions are:

From sunset to sunrise ■

In restricted visibility ■ , by day or night

And ■ whenever the Master considers it necessary.

Shapes are to be shown by day. They should remain hoisted after sunset and before sunrise, so long as they can be seen by other seafarers. During twilight, therefore, you should show both shapes and lights.

1Do remember that lights and shapes are always exaggerated in books like this. Real life is seldom so simple: lights will frequently be much more difficult to see, or lost against the background. Shapes may simply be wooded by the ship’s superstructure.

Rule 20

(a) Rules in this part shall be complied with in all weathers.

(b) The Rules concerning lights shall be complied with from sunset to sunrise, and during such times no other lights shall be exhibited, except such lights which cannot be mistaken for the lights specified in these Rules or do not impair their visibility or distinctive character, or interfere with the keeping of a proper look-out.

(c) The lights prescribed by these rules shall, if carried, also be exhibited from sunrise to sunset in restricted visibility and may be exhibited in all other circumstances when it is deemed necessary.

(d) The Rules concerning shapes shall be complied with by day.

(e) The lights and shapes specified in these Rules shall comply with the provisions of Annex I to these Regulations.

ch03.indd 20 3/10/10 3:29:41 PM

How to Recognise other Vessels by their Lights and Shapes: Rules 20–31 and 36 21

3

NAVIGATION LIGHTS

Side and Sternlights (Rule 21)

Side and sternlights, between them, cover the full 360 degrees of arc. Their purpose is to let you know that there is a vessel there and allow you to estimate its orientation2. Side and sternlights (unlike the masthead lights) are

displayed by very nearly all vessels under way at night or in restricted visibility, with only a very few exceptions3.

The port (red) and starboard (green)4 bow lights extend from the bow to the cut-in of the sternlight, 22.5 degrees abaft the respective beam, and the sternlight covers the stern sector, from 22.5 degrees abaft one beam, through the stern to the same angle on the other side.

There is no clever way of remembering 22.5 degrees, but it is an important angle because the Rules also stipulate that any vessel closing from within the arc of the sternlight, by day or night, is an overtaking vessel, with all the obligations that that brings (Rule 13b).

2Lights are profoundly important: it is well worth checking your own navigation lights each evening before sunset: check they work, check that they are not fouled by obstructions and, when you can, check that the cut-offs are as sharp as possible and there is minimal cross-over. For yachtsmen, make sure that you know which switches to make when you are sailing and when you are motoring. Setting the wrong lights makes you look shabby, and it can be profoundly confusing for other mariners.3Vessels Not Under Command; Restricted in their Ability to Manoeuvre, and Engaged in Fishing show side and sternlights only when making way.4‘Left’ has four letters, as does ‘port’ – which is of course a red-coloured wine, like the port sidelight.

A power driven vessel under way, showing side lights, sternlight and 2 masthead lights.

sternlight

portsidelight

starboardsidelight

masthead light(power only)

2nd mastheadlight (if fitted)

All lights cut off 22½° abaft the beam.

ch03.indd 21 3/10/10 3:29:41 PM

22 Learn the Nautical Rules of the Road

3

Masthead Lights (Rule 21)

Masthead lights are white lights carried at, or close to the masthead with arcs of visibility extending through the bow to an angle of 22.5 degrees abaft each beam. This is, of course, the arc of the two sidelights combined.

Power-driven vessels will generally carry two masthead lights, the after one discernibly higher than the forward one. If, however, the vessel is shorter than 50 metres in length, it may show only one masthead light.

Masthead lights are shown by nearly all power-driven vessels under way. They are also shown by sailing vessels operating under power, but not when sailing.

There are only a few types of power-driven vessels that don’t show masthead lights: Vessels Not Under Command, pilot vessels, and fishing boats Engaged in Fishing (although trawlers greater than 50 metres in length do).

IDENTIFICATION LIGHTS

Sidelights, the sternlight and masthead lights are all sectored. Identification lights, on the other hand, are generally visible around 360 degrees of horizon5 so that anyone approaching from any angle can see what is going on and decide what action to take. Identification lights are usually located below the masthead lights and above the side and sternlights.

5Towing lights are the only exception to this.

Power driven vessel, viewed from broad on starboard side – could be any length.

Power driven vessel, viewed from the starboard side – less than 50m in length.

ch03.indd 22 3/10/10 3:29:44 PM