Walk Ability May 2012

-

Upload

kimichelle523 -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Walk Ability May 2012

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

1/47

WALKINGThe Roman Street: An Assessment of Romes Walkability

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

2/47

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

3/47

Walkability is the extent to which the built environment accommodates the presence of

people and enables pedestrians to util ize the street as a resource. This study evaluates

walkability in Rome by identifying and examining four street types: the Medieval Street,

the Post-Unification Secondary Road, the Post-Unification Artery, and the Ancient

Consular Road. Case studies of Via della Lungaretta, Corso Vittorio Emanuele, ViaPrincipe Amadeo, and Via Prenestina were used as subjects by which to assess a

number of criteria shown in the literature to impact street aesthetics and functionality.

It was found that each subject street, as a representative of a type, satisfied some of

these criteria to varying degrees. The study concludes with policy suggestions for

place-makers to consider in addressing the walkability of Rome.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

4/47

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

5/47

Table of Contents

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

6/47

Introducing WalkabilityDefining Walkability

Walkability characterizes the pedestrians experience of moving abouta city. Whether walkers aim to reach a specific destination or aresimply on a leisurely stroll, a host of factors affect the ease or pleasure

associated with their experiences. Most of these factors fall within one of

two categories:

1) The aesthetic qualities of the street encompass properties of

appearance, such as building heights, enclosure, pavement type,

maintenance, lighting, and cleanliness.

2) The functionality of the street encompasses how the street is utilized

by pedestrians and includes proximity to gathering spaces, availability of

transportation routes, the presence of nearby landmarks, and access to

goods and services.

We propose that although there is no single ideal combination of

these factors, it is both possible and useful to identify trends in what makes

a place more or less walkable. Walkability is important for the functioning

of an urban space for many reasons, and we highlight a few below.

environmental benefits. In 2000, Urbanistica reported that most urban areas

have evolved from small pedestrian cities with dense centers into more

sprawling entities that are best labeled as automobile cities.1 Since this

transition from urban concentration to urban decentralization2 has

correlated with an increased carbon footprint, walkability has become an

increasingly important issue in discussions of sustainable transportation.

Today, traffic is responsible for about 50% of atmospheric pollution in cities

such as Rome.3

Just as reducing traffic congestion and pollution on astreet improves its walkability, choosing walking as an alternative to driving

reduces pollution levels.4 Further, if designers and builders keep in mind

the needs of walkers, the act of building new roads does not necessarily

harm the natural environment. A road conducive to walking promotes good

air quality, the balance of the water

cycle, reclamation of polluted

land, and general biodiversity.5

Moreover, studying

walkability can tease out issues

of environmental justice. For

instance, one study that aimed to

determine a walkability score for

Vancouver used residential density,

intersection density, retail floor-area,

and land-use mix found a relation

between income trends, walkability, and air pollution.6 In many areas, a lack

of walkability may be an important warning indicator of other more egregious

flaws in the urban setting, like the presence of caustic substances.

Public health benefits. Making urban spaces more walkable could ameliorate

the obesity crisis. In 2008, a study published in the Journal of Physical

Activity and Health found that countries with the highest levels of active

Walking and cycling distances in selected European countries and

the United States expressed in kilometers traveled per person peryear in 2000. Source: European Commissions Directorate-General

for Energy and Transport, the Danish Ministry of Transport, andUnited States Department of Transportation. 11

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

7/47

transportation (walking included) had the lowest obesity rates.7 Italy had a

9.8% obesity rate in 2005, a figure that contrasts markedly with the 33.9%

obesity rate in the U.S. reported in 2006.8

Although correlation does notimply causation, in the United States, health problems have been repeatedly

associated with suburban sprawl. For instance, a 2007 issue of Science

News told the story of Lawrence Frank, who moved from Atlanta, Georgia to

Vancouver and noted how the multitude of destination stores, restaurants,

and museums in Vancouver encouraged physical activity. (His former home

in Atlanta had been near to only one restaurant.)9 In Europe, restrictions

on car use, more convenient facilities for walking, and bike stations that

coordinate transit with walking encourage active transportation,10 which

may contribute to these differences.

cultural benefits. Walking is a particularly essential component of Italian

culture. The Italian tradition of thepasseggiata has roots in medieval times,

when families would go outside on Sundays for a stroll in the park or a

lap down a long via. Doing so demonstrated status and showed off the

family wealth to acquaintances and friends. The Italian notion of walkability

therefore encompasses the use of the street as a space for social interaction

and activity, not just for transport on foot. Today, Italian youth are increasingly

less likely to engage in these sorts of walks especially as the periphery is

built with few walkable features, with long distances between destinations

and many roads that do not lead anywhere directly. 12 The historic nature

of the city centers urban landscape is hence linked to the practice of the

leisurelypasseggiata.

the challengeof Planning rome: a contextfor Walkability

Romes ancient roots have long clashed with the perceived need tomodernize the city. On one hand, the city is an archaeological haven, and

urban developers respect it as a cultural artifact: a proposal approved by

Romes administration on 20 October, 2000 noted that Romes structure

should speak to the values of history and nature as inspiration for

contributing to creating identity.13 On the other hand, because the urban

landscape in the center evolved in a largely unplanned manner during the

Middle Ages, it renders many modern activities difficult a frustration that

has inspired efforts to completely gut parts of the historic center, such as

Mussolinissventramenticlearance projects (literally, disemboweling).14

This conflict between the ancient and the modern is perhaps more

pronounced in Rome than in other European cities because Rome occupies

and administers 129,000 hectares, an area greater than that of all the other

large metropolitan cities of Italy combined (Milan, Genoa, Venice, Bologna,

Naples, Bari, Catania, and Palermo).15 Such a grand scale exaggerates

infrastructural inefficiency.

Because Romes population boom occurred well after the booms

of cities like London and Paris, Rome was subject to a different set of

approaches to planning than were its European counterparts. When the

city became the capital of the Italian State in 1870 after the Risorgimento

(unification), it still only had 200,000 residents, so a complete spatial

restructuring was not necessary.16 By 1900, when the population finally

soared, the dominant philosophy in urban planning was that developers

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

8/47

should focus on the periphery instead of reshaping the center. Thus, Romes

center was never re-ordered into a grid-like or otherwise more modern

layout.17

The two predominant types of planning regimes it underwentwere the Umbertine and Fascist. The Umbertine practice was to clear areas

around the Capitoline Hill to create the Victor Emmanuel II Monument and

Via Cavour, and the Fascist attitude was to clear the area around the Imperial

Forums, excavate ruins, evict residents, and build EUR.18

According to Urbanistica, this relatively late

growth led to the genetic anomaly of Italian cities:

because they grew after the railroad boom of the

19th century, rail networks did not support growth,

and people instead relied more heavily on highways

for mobility.19 Romes first subway only went into

operation in 1955, and today Rome has a very high

rate of automobile ownership (over 700 cars per

1,000 persons).21 The ZTL (limtied traffic zone), which restricts automobile

access to residents of given areas, was established to reduce congestion;

nonetheless, in recent planning discussions, streamlining the mobility

system has been given top priority.22 Overall, Romes urban landscape

can be called polycentric,23 implying that there is a distinct disconnect

between activities in the periphery and in the center. The prominence ofroad-based transit means that the relationship between pedestrians and

cars is an indispensable focal point for studying Romes walkability, and

the distant relationship between the periphery and the center suggests that

walkability is experienced very differently in each setting.

Walkabilityinthe literature

A number of prior works framed our approach to investigatingwalkability in Rome. Kevin Lynchs The Invisible Cityprovided context for

the streets function in fostering urban identity. Interviews with citizens of

Boston, Los Angeles, and Jersey City indicated that the paths on which one

travels are one of the most important tools that citizens use to conceptualize

and order an urban space.24 A path may become special for a number of

reasons: frequency of use for commute to a destination, 25 concentration of

special uses along the path (such as a concentration of shops),26 distinctive

characteristics of building facades, proximity to important points in the city,

intersections with other streets,27 and directionality created by features such

as curvature.28 If a city has no major paths, or if those major paths are not

distinctive, the walking citizen can become confused by his surroundings.29

Thus, the urban artery is important in that it enables pedestrians to anchor

their journey through the street system.

Because walkability is about studying how pedestrians perceive

their surroundings, also of note are analyses of the process of vision.

Lynch defines the environmental image as a combination of identity

(recognizing objects as separate entities), structure, (discerning how the

object relates to other objects), and meaning (assigning a significance tothe object in the urban context).30 Similarly, Lise Beks description of vision

as a process, rather than a visual snapshot, discusses it as a reception of

meaning rather than a perception of form.31 It is not enough for a

street to be aesthetically pleasing for it to be walkable, because the walkers

zona traffico limitato traffic regulation.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

9/47

perception of his surroundings involves more than taking a visual snapshot

of the vista before him. Rather, there must be a dialogue between the

streets aesthetic and its functionality that enables pedestrians to assign itsignificance in their life.

Many works have aimed to identify criteria that can make a place

more walkable. One such endeavor is a paper with guidelines for the

Pedestrian Environment Review System, which identified the following five

Cs to explain walkability:

Convenience routes should facilitate the desired journey without

undue deviation or difficulty

Connectivity routes should link origins and destinations

Conviviality they should be pleasant to use

Coherence routes should be continuous

Conspicuity their design should allow the user to be seen by, and

to see, other pedestrians and vehicles to promote personal security and

road safety.32

These criteria serve as helpful overarching guidelines. The Via

dei Fori Imperiali in Rome, for instance, could be deemed convenient,

connective, coherent, and conspicuous, but its conviviality is dubious

walking amongst crowds of tourists and being heckled by street vendorscan be an unpleasant experience. However, a framework identifying even

more specific features would be even more effective in devising criteria for

walkability.

Much of what makes a streets walkability difficult to define is the

fact that streets are about social encounters and public access, not just

utility.33 In Great Streets, Allan B. Jacobs emphasized the fact that the street

is a political space whose goodness is determined more by its socialand economic qualities than its physical design. 34 Not only should a great

street help facilitate seeing and meeting all diverse kinds of people,35 but

it should also encourage citizen participation to stop to talk, sit, and watch

the goings-on in the neighborhood.36 An example of one such space in

Rome might be the streets surrounding Piazza Vittorio Emanuele, where

there is immense interaction among different immigrant groups. According

to Mario Spada, the former director of participatory planning at the Comune

di Roma, the space can be used as the population sees fit and enable all

kinds of exchanges because it is flexible, not because of any particular

architectural feature.37

As Mr. Spada mentioned,

however, a poorly designed

space will almost certainly inhibit

walkability.38 In Rome, design

can be extremely problematic at

the interface between pedestrian

and automobile traffic. In 2006,

pedestrian fatalities comprised14% of all deaths caused by road

traffic in 14 European countries.39

To study this trend, in 2010, a

study in European Transportationcrossing safety index flowchart for evaluating local pedestrian

safety. Courtesy European Transportation Review.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

10/47

Review devised an index for crossing safety to assess the ease of

pedestrian crossing.40 Safety was defined in terms of four categories:

Spatial and Temporal Design, Day-time Visibility, Night-time Visibility, andAccessibility.41 Night-time visibility was given the greatest weight (41%),

and the methodology was used to evaluate 215 pedestrian crossings in

17 European cities. The flowchart on the previous page shows a scheme

representing their findings. Safety was distilled into factors of spatial and

temporal design, day- and night-time visibility, and accessibility; and each

of these factors were subdivided into specific components. This type of

framework serves as a model for the more holistic framework of walkability

that our study compiles.

methoDology

Four principal street types were constructed to more easily classify

most streets in Rome. While not a comprehensive typology, these kinds of

streets were chosen for study because of their frequency within the city and

their vastly different levels of walkability.

1) The Post-Unification Artery: This is the wide, straight thoroughfare

cut through the citys medieval fabric once Rome ascended as capital of

the new nation of Italy. This street type has evolved to comprise some of thefastest and busiest vehicle routes through central Rome today.

2) The Post-Unification Secondary Road: Laid out in a gridlike

pattern, streets of this type feed into their larger arterial brothers. They are

characterized by their narrow width, abundance of storefronts at street level,

and uniform building architecture.

3) The Medieval Street: after a period of grid-like planning inspired

by Hellenistic influence during the 2nd century, Rome in the Middle Ages

saw a period of unplanned growth where winding streets and asymmetrical

marketplaces were the norm. The medieval street is the vestigial product

of this development.

4) The Ancient Consular Road: This type of street is comprised of the

main surface roads which lead into Rome from the periphery. Dating from

ancient times, these streets are now home to the products of the residential

building boom of the 1960s.

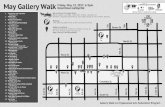

The map opposite depicts the streets chosen for closer analysis in the

following sections. The dimmed streets represent a small sampling of

analogous streets to help contextualize each street type.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

11/47

corso VITTORIO EMANUELE II

viaPREN

ESTINAviaPRINCIPEAMAD

EO

via della LUNGARETTA

0 1 mi.

The Four Roman Streets

Medieval Street

19th-Century Secondary Road

19th-Century Artery

Ancient Consular Road

subject of study

subject of study

subject of study

subject of study

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

12/47

via della LUNGARETTA

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

13/47

The Medieval Street

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

14/47

The Medieval Street has its origin in ancient Roman times and was

periodically modified by construction after the fall of the Roman Empire. As

a result of their more organically formed network than those of other streettypes in Rome, these streets have a curvilinear and disorderly configuration

that remains today. Via dei Giubbonari and Via del Governo Vecchio in

the Field of Mars are some examples of streets that originate from ancient

times and appear as they do today as a result of intermittent construction

over time. Many of these streets exist near the historic center of Rome, as

this is the only area in Rome that was consistently inhabited throughout

history from ancient times.

One of the best examples of

the transformation of a street from

ancient to medieval to modern is

Via della Lungaretta, which began

as an imperial intraurban highway.

Originally entitled Via Aurelia Verus,

it was renamed Via Transtiberina in

the fifteenth century, and then again

renamed Via della Lungaretta. Before

Viale di Trastevere was formed as

the main thoroughfare in Trastevere,this street was considered one of the

primary arterials in the neighborhood

and went in a straight west-to-east

line from the bottom of the Janiculum

Hill to the Tiber River.46 The street is

primarily a route for pedestrians and

a limited amount of local vehicles.

aesthetics

Via della Lungarettas

charming nature is reminiscent of

small street in a Tuscan town, with its

narrow, cobblestone path and light streaming into the street from above

low-rise buildings. This street is full of pedestrians, many tourists, at all

hours. The stretch that was studied was approximately 630 meters from

west to east and reached from Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere, across

Viale di Trastevere all the way to Piazza in Piscinula near the Ponte Palatino.

The section on the eastern flank of Via Trastevere was also included to

examine any differences between the two parts of the streets that was once

a continuous, uninterrupted length of street.

The narrow width of the Via della Lungaretta does not impede the

walkers ability to move along the street. With a large portion of the street

designated solely for pedestrians by concrete barriers, the pace of the street

is much slower than that of a street intended for vehicle traffic. Crossingthe larger Viale di Trastevere is facilitated by a well-marked crosswalk and

stop light, enabling pedestrians to access both sides of the street with ease.

As in its ancient past, this street is mostly straight with a small degree of

curvature to it at each end of the observation area. Few streets intersectThe classic curvilinear medieval street layout. Courtesy Michelle

Kim.

Vehiclebarriers.CourtesyMichelleKim.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

15/47

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

16/47

Via della Lungaretta, and those that do are extremely narrow vicoli; they do

not visually direct the pedestrian off the course of the street. Moving into

the large Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere, pedestrians are immediatelydrawn into the center near the fountain, because the seating for two

restaurants that abut the piazza redirect pedestrian traffic into the piazza.

Many small piazzas with vehicle parking and some restaurants frame the

street at various intervals, allowing gathering space and light to flow more

freely into the street. This is a highly active street, with a large number of

pedestrians utilizing the street as a destination rather than as a mere path.

Many stop at different restaurants and boutiques, and a number of tourists

stop to look at trinkets from street vendors.

Overall, the street appears well-kept, with planters and vines lining

buildings, despite the poor maintenance of a number of buildings on both

the eastern and western sections of the street. Although this street is merely

two blocks from the high-traffic Lungotevere Raffaello Sanzio and also

intersects the busy Viale di Trastevere, vehicle noise on the street is limited

and makes the street refreshingly detached from the bustle of the city.

functionality

Although Via della Lungarettais considered a small street, its role

as a connector from busier areas to

its primary landmark, Chiesa di Santa

Maria in Trastevere, allows it access

to transit. Viale di Trastevere, its

bisector, has a number 8 tram line

running its length from the city centerto Casaletto and facilitates pedestrian

traffic from Trastevere in and out of

the historic center. Though the tram

cuts through the middle of Viale

di Trastevere, there is an adequate

crosswalk and stop light to facilitate

movement across the street from one side of Via della Lungaretta to the

other.

In addition to the many restaurants and cafes that line the streets,

there are fairly limited services on the western part of the street besides a

pharmacy and a bookstore. However, all the services necessary to residents

are located in close proximity to Via della Lungaretta. On the eastern portion

of the street, there are far fewer restaurants and more small clothing and

gift boutiques, as well as some produce stands used by locals. Although

the eastern side has a more diverse set of services, there is less space to

sit and relax, indicating that this portion of the street is not viewed as a

destination, like the western side, but more as a thoroughfare.

Poor maintenance stands out amidst medieval charm. Courtesy

Michelle Kim.

Oneofmanycommercialoutletscateringto

tourists.CourtesyMichelleKim.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

17/47

17

46

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

18/47

via PRINCIPE AMADEO

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

19/47

The Post-Unification Secondary Road

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

20/47

Post-Unification Seondary Roads were often laid out as parallel

streets to major contemporary arteries and thoroughfares. Constructed

during a period of large urban development in Rome, these streets are builton a gridded system, as opposed to the meandering medieval street types

found around the Field of Mars. This more orderly street structure allows

for easy access and wayfinding, with each end of each street ending at

a major arterial. Streets of this type include Via Aldo Manuzio and Via

Alessandro Volta in Testaccio, Via Angelo Poliziano on the Esquiline Hill,

and Via Fabio Massimo in Prati.

Via Principe Amadeo, two blocks west of Termini Station, is an

especially notable example of this street type. Its 1.16-kilometer span is

straight for its entirety, ending at Via del Viminale to the northwest and Via

Cairoli to the southeast. It also has two major bisecting streets, Via Cavour

and Via Gioberti.

Because of its proximity to Termini, the northern end is lined with

hotels serving the major transportation hub of the city. To the south, the

buildings become increasingly more residential and the street eventually

ends parallel to Piazza Vittorio Emanuele. Toward the center of the street

is the Piazza Manfredi Fanti, a rectangular wooded piazza defined as an

interruption of the fabric mesh of isolatiof the new quartiere; a gap in thegeometric checkerboard design, no different from that which determines

the other squares of the neighborhood, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele, Piazza

Dante, and Piazza Guglielmo Pepe.47 These are all examples of piazzas

that signify breaks into the geometric pattern of street and edifices.

aesthetics

As part of a gridded streetsystem there is a clear directionality to

the layout of the street. The buildings

are mid-rise, ranging around seven

to eight floors on both sides of the

street. The buildings seem high, but

there is much street engagement on

the ground level with shops, hotel entrances, and restaurants at the north

end. Via Principe Amadeo is a one-way street that alternates direction at

each subsequent intersection, further emphasizing its use as a secondary

street in which a car is not expected to stay on it across its entire length.

The sidewalks are wide, at eight feet, and give ample space for pedestrian

traffic. There are also many tents along the sidewalk for the outdoor seating

areas of hotels, restaurants, and other cafes.

During the day, there are many people along the sidewalks, although

vehicular traffic is not as common, with the street primarily used for parking

off the main arteries of Via del Viminale, Via Cavour, Via Gioberti, and

Via Cairoli. Most of the moving vehicular traffic is along these streets.

There are many opportunities to cross the street at designated pedestriancrosswalks or in other places with little traffic along the one-way lanes.

There are often double-parked cars, which makes it difficult to get across

the street at undesignated crosswalks.

Engagedstorefrontsonasidew

alkwith

multipleprograms.

CourtesySp

enser

Gruenenfelder.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

21/47

The Post-Unification Secondary Road

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

22/47

Via Principe Amadeos position on a grid eases wayfinding,

especially to nearby landmarks and services. In terms of security features,

there are overhead street lights across the length of the road as well asmany lights outside the hotels and shops along the street. There is always

a presence of people on the street coming from the hotels, heading to such

landmarks as Termini Station, sitting at the outdoor seating in front of the

restaurants, or just strolling.

The upkeep of the area is

very good at the north end with

the many hotels keeping the area

in good physical repair. The only

permanent greenery is found at the

Piazza Manfredi Fanti and in two

courtyards of adjacent apartment

complexes. This is mostly due to

the limited width of the street and

sidewalks preveting easy installation of plantings. The restaurants and

hotels make up for any lack of street trees by having planting beds by the

doors and along the outdoor seating.

functionality

Via Principe Amadeo is in a very central location near Termini Station,

allowing for much access to public transportation, by walking two blocks

to Termini, a major transportation hub. Augmenting the trains and trams

are many bus routes along Via Cavour, Via Gioberti, and Via Napoleone III

that intersect or are directly parallel to Via Principe Amadeo. Also in the

neighborhood are the Repubblica, Termini, and Vittorio Emanuele metrostops on the A line.

It is in close proximity to other landmarks as well such as the Basilica

Santa Maria Maggiore, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele, Piazza della Repubblica,

and the Teatro dellOpera. Accessing these landmarks of the neighborhood

is very simple due to the gridded street system. There is also easy access

to important goods and services along Via Principe Amadeo, including

to stores, shops, social services, and the green space of Piazza Manfredi

Fanti. Other services are easily found along close adjacent streets.

Transit lines pass easily through the gridded streets of Post-

Unification Rome. Courtesy Spenser Gruenenfelder.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

23/47

25

85

8 8

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

24/47

corsoVITTORIO EMANUELE II

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

25/47

The Post-Unification Artery

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

26/47

Post-Unification Arteries were built, naturally, after the unification

of Italy in 1861. With Rome as the capital of the newly established nation,

there was an anticipation of increased pedestrian and carriage traffic

through the citys historic center. The construction of roads such as Corso

Vittorio Emanuele II, Via Nazionale, Via Tritone, and Via Cavour required the

demolition, modification, or relocation of thousands of buildings, some of

which dated back to medieval times, in the roads intended paths. The more

cultural or historic value the building was deemed to have, the more care

was taken in preserving it during the construction of the arteries. 48

Numerous examples of this kind of preservation occur on Corso

Vittorio Emanuele, the subject for the study of this major street type. This

particular street is the principal east-west thoroughfare through the Field of

Mars, the historic heart of Rome where most of the citys tourist sites are

found and the only continuously occupied area of the historic center of the

city. The four lanes of Corso V. Emanuele connect Piazza Venezia in the east

with the Vatican in the west. The road is a principal route for public and

private buses, taxis, and private automobiles through central Rome.

aesthetics

Corso Vittorio Emanuele IIs loud, bright intensity contrasts sharplywith the tranquility of its narrow medieval neighbors. Its appearance remains

consistent for its entire length, with imposing Renaissance- and Baroque-

era palaces and churches pushing seemingly to its very edge. It is one

of very few streets of such carrying capacity in the Field of Mars, and as

such it receives a tremendous amount of vehicle and pedestrian traffic. The

portion observed for the purposes of this study was a half-mile (seven-

hundred meter) stretch from Largo Argentina in the east to the Chiesa Nuova

in the west.

The Corsos width diminishes the sense of enclosure that would

normally come from walking between buildings averaging around a hundred

feet tall. The east-west orientation of the street, and the lack of significant

interruptions in the building fabric on either side, means that the street sits

in either intense sun or deep shade, depending on the time of day and side

of the street. Whether it is cold and windy or hot and bright, the pedestrian

on this street will feel it more strongly on the Corso than on a narrower,

more curvilinear street.

The street is designed, first and foremost, for easy and fast vehicle

travel. This characteristic manifests itself in a number of ways and has

direct implications for the walking experience. The narrow medieval cross

streets, with few traffic controls

necessary for pedestrian safety,

make walking along one side of the

Corso a simpler affair than crossing

it. Sidewalks are of smooth asphalt,but are too narrow for the amount of

pedestrian traffic they receive.

At many points along the street, a

historic faade juts into the sidewalk,Tourists spill off of Corso V.E. IIs crowded sidewalks. Courtesy

Charles Bailey.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

27/47

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

28/47

narrowing it further or eliminating it altogether. Crossing the street is a

tense and unwelcome experience. The streets width, the speed of its

traffic, and its dearth of crosswalks forces pedestrians to crowd around

just a few signalized intersections. The narrow sidewalk width means thatthey pour into the street while waiting to cross, making a stressful situation

dangerous.

Despite its issues with pedestrian movement, actual navigation of

the Corso is simple, especially to a walker remotely familiar with Rome.

Signage directs visitors to nearby

landmarks, and often the only possible

directions in which to walk are east and

west if on the street, and north and southif walking on a perpendicular street.

The ambiguously accessible spaces

commonly found on other Roman street

types are absent on the Corso: if there

is a wall, the path is blocked, and if not,

the path is open.

Corso Vittorio Emanueles high levels of traffic of all types makes

it a hub of activity. Even late at night, most pedestrians would feel asthough other eyes are present on the street, if not from buildings then from

other street users. Lamps, hung from wires strung over the street between

buildings, add to the streets security. A drawback is the lack of engagement

of the street from the many businesses that line it. On Sundays and late at

This palace facade, preserved during the roads construction,

narrows its adjacent sidewalk to roughly two feet. Courtesy C. B.

47 74 6

95

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

29/47

night, many of them shut their doors,

turning storefronts into disconcerting

metallic walls.

In the ancient streets of

central Rome, plantings or green

spaces of any type are at a remarkably

high premium. This holds true on

the Corso. The only plant life to be

found in the half-mile stretch walked

for study was the few trees lining

the Piazza della Chiesa Nuova. The

rest of the streets materials consistsof asphalt, travertine, and other

concrete-like surfaces. The faades

of the many palaces lining the Corso

are severe, thick, and heavy. The lack of windows at eye level creates a

sterile and uninviting environment for the pedestrian. While eyesores such

as graffiti and litter are few on the Corso, the pollution-stained monolithic

palace faades seem almost as visually unpleasant.

functionality

As the main street of the Field of Mars, Corso Vittorio Emanuele

benefits from excellent connectivity to its vicinity and the rest of Rome.

Much of the streets high traffic comes from the many bus lines that run

its length, offering access to the trains, subways, trams, and other buses

which circulate throughout the city and connect it to the rest of Italy. An

abundance of bars, restaurants, and travel agencies lines the street, serving

tourists needs more than adequately. Innumerable landmarks line and

surround the Corso, making it a destination in its own right. The services

city residents need for daily life, however, such as groceries, post offices,

and other goods stores, are much harder to find, suggesting that this corner

of Rome has few Romans actually living in it. There is almost nowhere to

stop, relax, and enjoy the city.

Excellenttransitaccesscomesatthepriceofpackedsidewalks.Courtes

yC.B.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

30/47

via PRENESTINA

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

31/47

The Ancient Consular Road

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

32/47

Streets of the Ancient Consular Route type were historically transport

arteries from Rome to nearby towns, and they continue to serve as impor tant

throughways. They are wide, are linked to public transpor t by tram or metro,

and have well-maintained, concrete pavement suited to automobiles. Often,

they serve as landmarks in that they bound a neighborhood or enable mass

transport through its center, and nearby housing is typically apartment-

style and modern. Via Aurelia, Via Cassia, Via Flaminia, Via Salaria, Via

Nomentana, Via Tiburtina, Via Casalina, Via Appia, Via Ardeatina, and Via

Ostiense are some examples.49

An exemplary street of the consular type, Via Prenestina,

constitutes an east-west axis that begins at Porta Maggiore and continues

for approximately twenty miles to the city of Palestrina (in ancient times,Praeneste).50 Via Prenestina was originally named for the road head

Praeneste, and it is the modern form of the ancient Via Praenestina that

linked the Tiber to the eastern hills. Notable ruins, such as the Torrione

Prenestino tumulus tomb, Columbarium in Largo Preneste, the Villa dei

Gordiani, and the necropolis at Osteria dellOsa51 contribute a historic feel

that coexists with the modern, sometimes-industrial architecture. Nearest

Romes center, Via Prenestina constitutes the northern border of Pigneto

and Centocelle; it falls south of the Portonaccio and Tiburtina areas.

aesthetics

Via Prenestina combines a modern architectural aesthetic with a

sense of open space and timelessness. The street changes dramatically

moving eastward from the city center.

Where the street begins in the west,

buildings are constructed close

together with an urban, industrial

feel. Moving eastward, edifices

become more interspersed with open

space and countryside, and the street

assumes the ambiance of a scenic

highway. The juxtaposition of mid-

20th century architecture with the various ruins is a unique experience of

the Roman periphery.

Building heights are relatively low, and most structures have amaximum of eight stories. The street itself is wide, such that during daylight

hours, the sun beats down to pedestrian level and illuminates the space.

The width also prevents interplay between both sides of the street, as it

is not possible to walk on one side and observe the activities or potential

destinations on the other. Pedestrian

walkways line both sides of the

street and vary in width, but most

are wide enough for the comfortable

passage of walkers in both directionssimultaneously.

The presence of greenery

along Via Prenestina increases

ViaPrenestinas

midcenturyapartmentblocksand

wideintersectionsatnight.CourtesyE.Gould.

Wide streets with impenetrable barriers make cross-street

interaction impossible. Courtesy Emily Gould.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

33/47

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

34/47

moving eastward. Nearest Porta

Maggiore, trees are landscaped

intermittently along the tram route at

the center of the street, and umbrella

pines are increasingly present along

the street continuing past Via Tor

de Schiavi. These pines contribute

to the highway ambiance but also

gave the sense that this street leads

somewhere important, referencing the passage of time and the rich history

of the route.

In various areas, there are bouts of fenced-off construction thatinterrupt the continuity of the walking space. Banisters offset the trafficked

street from the pedestrian walkway, and parked cars create a barrier between

the walkway and the street. In some stretches, cars are parked such that

they protrude from the curb perpendicularly, so they increase the sense

of distance between the walkway and

the opposite side of the street. They

also increase the separation between

the walker and the heavy flow of traffic

that moves along the Via.

Ease of crossing the street

varies depending on the intersection.

At designated points, traffic lights

clearly signal for cars to stop and

change frequently enough to permit

stress-free crossing across the width

of the Via. At others, especially when

major streets feed onto Prenestina,

the tram constitutes a barrier, and

the lack of lights necessitates

waiting a long time for an opening

in the through traffic. These major

intersections often serve as the dominant focal points of the vista along the

street, so the pedestrian can use them as landmarks.

Pavement is concrete, well-maintained, and suited to automobileflow; signage is occasionally difficult to locate due to the street width; and

the street is generally straight. At night, lamps are scarce, and graffiti that

could be considered decorative during the light of day takes on a more

menacing character. Dumpsters are found along the street in some areas,

and litter is not a significant presence. Many housing projects line the

street. The ground stories of buildings are occupied by small cafs and

boutiques. The street serves as a commercial hub for the residential areas

that flank it. There are also a number of gas stations and supermarkets.

functionality

The 5, 4, and 19 trams follow Via Prenestina together until Tor de

Schiavi, at which point the 5 and 19 veer southward into Centocelle while

Construction walls block pedestrian paths. Courtesy E. Gould.

Wide crosswalks facilitate movement. Courtesy Emily Gould.

Wideopenstrec

thesofpavementatintersections

aredauntingtoapproach.CourtesyE.Gould.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

35/47

the 14 continues to Togliatti. These trams provide accessibility, but they also pose an obstacle to street

crossing as they are, in places, offset from each half of the street by a metal barrier. A number of buses also

run along sections of Via Prenestina, and parking spaces are widely available. Thus, the street is tailored to be

a quick path from starting point to destination.

There are not many features inviting the pedestrian to turn off of Via Prenestina to the smaller streets

that border it. Boutiques and coffee shops continue to line streets to the north and south, but the walker must

generally have a destination in mind, as these places are not clearly identifiable. Adjacent green spaces, such

as the Villa Giordini, add to the presence of natural features, and there are numerous supermarkets and gas

stations.

Via Prenestina also has a very diverse pedestrian demographic. People of all ages can be observed

out and about around 5 pm, and ethnicities are varied. Although there are not many stopping points along thestreet that are designed for gathering, passersby are able to pause and interact when necessary. For the most

part, however, walkers are out for the purpose of reaching a destination, such as returning home from grocery

shopping.

8 95 12

85

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

36/47

Evaluating Romes StreetsOne significant challenge in determining a particular sites

walkability is the subjectivity of the definition of walkability itself -- there

is no one formula to make a street walkable. A street may be designed

according to specific guidelines to be walkable, but it may still be an

unpleasant place to walk. This study has attempted to identify a number

of industry standards with which to assess walkability, with the goal of

producing recommendations for policy changes in the city of Rome. The

following section dissects poignant characteristics of each of the streets

chosen for study and uses these standards to assess their walkability.

viaDella lungaretta

Via della Lungaretta is largely geared towards pedestrian traffic andis more a social space than a pathway. Both eastern and western portions

of the street begin and end with piazzas, and several other piazzas branch

off in between. These piazzas formally serve as gathering spaces that are

fused with the street. With a slow pace to the street and an abundance

of restaurants, cafes and street vendors, pedestrians are not pressured

to rush along the street and are

more likely to interact with their

environment.

In the context of the disorderlymedieval street system, these

streets have no consistent pattern

and are thus seemingly difficult

to navigate from inside a vehicle.

However, according to Mario Spada, the former director of participatory

planning at the Comune di Roma, Romans still prefer to drive these streets

than attempt to navigate them on foot. However, these medieval streets

are generally walkable, because they are lined with various interesting

destinations and services that promote activity along the street.

via PrinciPe amaDeo

With wide sidewalks along primarily one-way and one-lane streets,

Via Principe Amadeo is designed to be pedestrian-friendly. Its placement

within a grid system means that it is entirely straight, with many crossing

perpendicular streets for easy access to nearby landmarks and parallel

streets. As a secondary street,its main use is for parking

and accessing the hotels and

residences along it. Because of

its secondary use for vehicular

traffic, it allows more and safer

uses for pedestrians. Its proximity

to Termini Station provides easy

access to many forms of public

transportation, including localbuses, tram lines, metro lines, and train lines to the outskirts of Rome and

other cities.

A strong benefit to the walkability of Via Principe Amadeo is the large number

of tents lining the sidewalk for outdoor seating from the hotel restaurantsA pedestrian on Via della Lugnaretta is conspicuous. Courtesy

Michelle Kim.

Hotels,cafes,andcommuterscoincidepeacefully

onViaP.Amadeo.CourtesyS.Gruenenfelder.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

37/47

and cafes. They divide the pedestrian uses from the street, are aesthetically

pleasing, and in good weather are always active.

Many streets in Rome are of Via Principe Amadeos type. From

Testaccio to Prati to San Lorenzo, these streets are home to much of central

Romes population. Their geometric simplicity, narrow width, and clear

delineation of pedestrian and vehicular uses allow them to meet many of

the established standards of walkability. There is some variation within the

Post-Unification Secondary Road type in terms of states of upkeep and

number of services and amenities. The basic design of this street type,

however, is consistent throughout the places in Rome where it is applied.

corso vittorio emanuele

An ideally walkable street is both a path and a destination. Corso

Vittorio Emanuele is an excellent path, but a poor destination. Functionally,

its transit connections, continuity, and traffic capacity fully satisfy the

standards for walkability established in the study. Pedestrians pack its

sidewalks, and its bus stops facilitate travel all over the city. Hundreds of

famous landmarks lie within easy walking distance, as do the many other

services that cater to tourists, such as restaurants and bars.

Corsos utility, however, comes at the steep price of aesthetics.

Heavy, dark facades, impossibly narrow sidewalks in proportion to the largevolume of pedestrians, loud traffic noise, and difficult crossings make the

experience of using this path through the Field of Mars one to be dreaded.

The nineteenth-century practice of carving through the medieval urban fabric

may have worked in an age of horses and carriages, but the automobiles

size and noise fit the same spaces awkwardly today. The same walkability

issues that plague Corso Vittorio

Emanuele also affect other streets

of its type.

These streets are the ones that

welcome many visitors to Rome;

the Via Nazionale, Via Cavour, and

Via Labicana all connect to Termini

Station. They all share the transit

connectivity and access to goods,

services, and landmarks afforded

by Corso Vittorio Emanuele, but

fail to meet the basic aestheticstandards for ideal walkability.

It is regrettable that these roads,

some of the most traveled in the

city, provide such a stressful walking

experience and thus a poor first impression for the visitor.

via Prenestina

Via Prenestina has abundant transit access and has wide sidewalksfor pedestrians, but it ultimately lacks the intimacy of the most walkable

of streets -- largely because the tram, parked cars, and large street width

form a barricade between the pedestrian and the features across the way.

Elements of the street architecture are largely nondescript as well, which

This heavy facade hides the fact that at least five businesses openonto the sidewalk of this building on C.V. Emanuele. Courtesy C.B.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

38/47

gives the street a more developer-

built and impersonal feel. The

street serves to provide the space

for trams and buses and filter

traffic in from outside of Rome,

and enables people to travel from

origin to destination efficiently,

but for the leisurely stroll, it is not

ideal.

The majority of the Ancient

Consular Routes are similar to

Via Prenestina in that they are

mostly wide boulevards with hightraffic densities that lead into and

out of Rome. They are primarily

walked out of the necessity to

reach a destination, like the grocery

store or a tram stop. They are paved with concrete and lined with modern

architecture, especially as they radiate outward from the city center toward

the periphery. Thus, while they are efficient and house a diverse population,

they are not designed to create visual focal points that provoke a dialogue

between the pedestrian and the urban landscape.

As urbanist Allan Jacobs noted in Great Streets,52 the most

pleasant streets to walk are ultimately those that serve as social spaces

and provoke a dialogue between the pedestrian and his environment -- not

those that simply enable people to walk from their starting point to their

destination. Each walkable street achieves this effect in a different manner.

The following diagram distills what this paper has defined as

walkability into its various components, providing a framework for

evaluating any given street. This framework breaks down what qualities

form the duality of aesthetics and functionality.

The following are sub-components of aesthetics:

enclosure is the sense of feeling indoors. Building heights have greatimpact on enclosure because, for instance, a narrow street with towering

buildings that block the sunlight can be claustrophobic for the pedestrian,

whereas a narrow street with low buildings can feel open and expansive. A

wide street can be overbearing and lead to a lack of intimacy between the

pedestrian and his surroundings, but width can also be advantageous if it

contributes to a sense of wilderness and light. If trees are planted along

the street, their maintenance and spacing has vast impact: a street with

only a few token trees can seem very industrial, and to the other extreme,

streets with overgrown greenery can seem under-maintained. Variations inbuilding heights, widths, and presence of greenery can create focal points

that make the street interesting to walk, as long as architectural cohesion

is maintained.

Ancient Consular Roads like Via Prenestina accomodate high levels ofall forms of traffic. Courtesy Emily Gould.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

39/47

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

40/47

navigability can be assessed in terms of mobility - the ability to physically

move from point A to point B on the street with ease - and wayfinding, or the

ability to navigate the street without frustration or disorientation.

Mobility: The ease of moving up and down and the ease of crossing

are affected by specific design features such as parking sign placement, the

number of streets that intersect at a given point, and traf fic light functionality.

If pavement is poorly maintained, for instance, surface cracks can make the

act of moving slow and dangerous.

Wayfinding: Ideally, streets should be marked with visible signage

that appears often enough to serve as a reference at any moment. Curvature

can create a sense of mystery and accessibility, but if a street is too windy

it can disorient the walker. Permeability of edges refers to the degree to

which a streets role in the greater urban plan is evident - is it a major streetthat enables ordering, or is it an accessory connector street? - and how

seamlessly it connects to streets that may offshoot, both physically and

commercially.

security includes lighting of the street at night and community engagement,

which encompasses factors of the physical aesthetic that reflect how much

respect residents exhibit for the area. For instance, excessive graffiti can

create a sense of insecurity for the walker, who may infer that there are

undertones of anger among the population that could also be outlet in amore violent manner than street art. In addition to contributing to this sense

of care for the neighborhood, litter on the street can also sometimes reflect

a lack of a well-functioning system of trash collection or policing.

architecture of a walkable street can come in infinite forms. However,

stylistic cohesion is nearly always important, because it creates a sense

of intention and care in the urban design. A street with haphazard building

heights, widths, materials, and facade features can feel hectic and confused.

Design features such as fountains, benches, and statues are also important

in that they create focal points for the walker. Without them, the street may

lack intimacy and character.

activity refers to the physical elements of peoples use of the street.

Pedestrian density is relative to sidewalk width. If a street is extremely narrow

and has a multitude of pedestrians in a small space, it can appear chaotic

and discouragingly crowded; likewise, if a street is wide and has very few

pedestrians, it can seem isolated and perilous. Dense, fast-moving vehicletraffic and high noise levels can also detract from the streets walkability.

The following are sub-components of functionality:

transPortation to and from the street is extremely important, because it

affects pedestrians reasons for walking, their ease of arrival at the street,

and experience of the spaces goals. For instance, on a street next to a

transportation hub, most people may be walking as part of their daily

commute to arrive at work or return home; then, the street becomes animportant physical path, but not a place for extensive social gathering.

Ideally, transportation is frequent, reliable, and well-connected to the rest

of the neighborhood and city; however, if the transportation itself becomes

the main focal point of the street, the walker can feel excluded from the

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

41/47

urban setting and must navigate the transportation infrastructure like a

physical obstacle.

commerce anD access describes the kinds of goods and services on the

street. Accessibility of goods and services includes (but is not limited

to) whether storefronts are set up in an inviting manner, whether a range

of goods and services are on offered along the street, and whether these

resources are laid out in an easily navigable manner. (For instance, having

to cross the street excessively to window shop is an unpleasant experience

for the walker.)

afforDability refers to whether the goods and services on offer are suited

appropriately for the social demographic of the walking population. A streetlined with only high-end outposts can seem sterile and frustrating, and

similarly, a street that only has seedy shops selling bootleg handbags can

seem crass.

sociability of the street is defined by aspects of the demographics and physical

layout that contribute to the areas function as a gathering point and place

of social exchanges. Ethnic diversity, handicapped accommodation, and

socioeconomic diversity foster the notion that a given street has something

to offer anyone who chooses to walk along it.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

42/47

Policy SuggestionsAs drawn from observations of Roman streets and the authors

research process, no single physical or functional design of a street can

determine whether or not it is walkable. It is imprudent to walk out onto

a street with a checklist and tally up the walkable versus non-walkable

components to ascertain the degree of its pedestrian-friendliness. This

sort of methodology is too systematic and calculated, whereas the issue

of walkability is dynamic and heavily contingent upon environmental and

historical contexts. It is important to take a step further than reporting and

analyzing observations by presenting overarching policy recommendations

that place makers, specifically in Rome, should employ to foster truly

walkable streets.

One of the most important policy approaches is through zoning.

Zoning regulations for a city can facilitate or severely impede the creation ofwalkable environments. For instance, minimum street width requirements

for certain types of arterials can encroach upon available pedestrian space

and cause the narrow sidewalk issues that are present on Corso Vittorio

Emanuele II. On the contrary, zoning certain areas as pedestrian only,

as exists on some small medieval streets within Rome, removes all the

barriers to walkability afforded by automobiles. In addition, land use laws

that encourage resident involvement in public spaces should be promoted,

with uses such as small-scale retail, restaurants, other commercial

establishments, bringing citizens out into open public space.While zoning and land use regulations can put walkability guidelines

on paper, such guidelines must also be enforced by those with authority. In

too many cases, though, especially in Italy, there are instances of negligent

permitting that allow variations in setback from the street, building height,

sidewalk width, an inadequate number of pedestrian provisions, and street

lighting. These aberrations to the norm can either make a portion of the

street appear disorganized or make the whole street look so fabricated as to

be artificial. More importantly, inconsistencies in permitting create safety

concerns for pedestrians by not providing adequate physical protection for

them, such as sidewalk bollards or street lighting. By strictly enforcing

land use laws and construction codes, place-makers can avoid the potential

negative effects of atypical building construction, substandard material

quality, or inadequately addressing pedestrian needs.

The most obvious and direct policy intervention is through design.

Although the word design itself is often used in a largely artistic context,

human-centered design is an approach to urban design that puts the

behaviors, needs and potential of humans before those of automobiles.There are many functional design measures that can be quickly and

affordably implemented to enhance the pedestrian environment. These

include transparent building fronts for free movement between the indoors

and outdoors, stratified path materials to delineate pedestrian walkways

from vehicle zones, and traffic-calming measures, such as stop lights with

complementary crosswalks or sidewalk extensions into the street to make

the street narrower to slow down vehicular traffic. Overall, design should

actively address pedestrian issues as a priority when planning or modifying

a streetscape.The policy suggestions above call for concrete and measurable

improvements. However, building and designing are not the only answers

to future problems with walkability in Rome. Italians are a walking, strolling

culture, and all the new and existing spaces where they live, work, and play

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

43/47

should reflect this quality. Those in control of Romes future development

should craft new spaces with a sensitivity toward the Italian passion for

walking. This passion sets the country apart from countless other places

around the world.

Roman planners should take advantage of their ability to both improve

citizens quality of life and the quality of the natural environment. Luckily,

the application of measures for walkability tackles both issues at once.

Walkable streets have been shown, among many other improvements, to

increase citizens engagement with their communities, reduce their carbon

emissions, make them healthier, and make them spend more locally. This

method of transportation, as old as humanity, is efficient and essential for

the modern city dweller.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

44/47

Notes1. Stefano Gori, Marialisa Nigro, and Marco Petrelli, The impact of land use

characteristics for sustainable mobility: the case study of Rome,European

Transportation Review, 14 March 2012, 1.

2. Ibid.

3. Franco Archibugi,Rome: A New Planning Strategy (London: Routledge,

2005), 52.

4. Germana Minesi , ed. Translated by D. Borri and Ilene Steingut. Urbanistica,

Jan-June 2001, 262.

5. Ibid.

6. Tanya Tillett, MA, of Durham NC. You Are Where You Live: The

Interrelationship of Air Pollution, Address, and Walkability.Environmental

Health Perspectives, November 2009, 505.

7. David R. Bassett, Jr., John Pucher, Ralph Buehler, Dixie L. Thompson,and Scott E. Crouter. Walking, Cycling, and Obesity Rates in Europe,

North America, and Australia.Journal of Physical Activi ty and Health no. 5,

2008. This study examined the relationship between active transportation

and obesity, and it compiled national surveys from 1994-2006 of travel

behavior and health indicators in Europe, the North America, and Australia.

8. Ibid.

9. Ben Harder, Weighing in on City Planning, Science News, 20 January

2007, 43.

10. Bassett, 795.11. Ibid., 808. The average European walked more than the average US

citizen (382 versus 140 km per person per year) in 2000.

12. Mario Spada, personal correspondence, 3 May 2012. Mr. Spada

worked in the Planning Department of the Rome City Council on the issue

of regeneration of the peripheries. He also organized the INU Biennial of

Public Space.

13. Minesi, 222.

14. Zeynep Celik, Diane Favro, and Richard Ingersoll, Streets: Critical

Perspectives on Public Space (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1994), 9.

15. Minesi, 280.

16. Archibugi, 2.

17. Ibid., 3.

18. Ibid., 18.

19. Minesi, 220.

20. Minesi, 217.

21. Gori, 5.22. Minesi, 217.

23. Ibid., 222.

24. Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1960), 49.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid., 50.

27. Ibid., 51.

28. Ibid., 54.

29. Ibid., 52.

30. Ibid., 8.31. Beck, Lise in Algreen-Ussing, Gregers, Lise Bek, Steen Bo Frandsen

and Jens Schjerup Hansen, ed. Urban Space and Urban Conservation as

an Aesthetic Problem: Lectures presented at the international conference in

Rome 23rd-26th October 1997. Rome: Lerma di Bretschneider, 2000,

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

45/47

60.

32. Stuart Reid, Pedestrian Environments: A Systematic Review Process.

Available On-Line at [http://www.walk21.com/papers/Reid.pdf], 4.

33. Allan B. Jacobs, Great Streets (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, 1993), 3.

34. Ibid., 6.

35. Ibid., 8.

36. Ibid., 9.

37. Mario Spada, personal correspondence, 3 May 2012.

38. Ibid.

39. Thomas Leitner, Stefan Hoeglinger, George Yannis, Petros Evgenikos,

Niels Bos, Martine Reurings, Jeremy Broughton, Brian Lawton, Louise

Walter, Manuel Andreu, Jean-Francois Pace, and Jaime Sanmartin, TrafficSafety Basic Facts 2008: Pedestrians,European Road Safety Observatory,

October 2008, 1.

40. Olga Basile, Luca Persa, and Davide Shingo Usami. A methodology to

assess pedestrian crossing,European Transportation Res. Rev(2010) 2,

129.

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid., 132.

43. Algreen-Ussing, 50.

44. Ibid., 56.45. Ibid.

46. Zeynep.

47. http://www.casadellarchitettura.it/stampa/storia.html

48. Agnew, 230.

49. Lenzi, 156.

50. The Via Prenestina: The Mountain Route to the South. Provincia di

Roma. http://en.tesorintornoroma.it/Itineraries/The-Via-Prenestina.

51. Ibid.

52. Jacobs, 270.

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

46/47

Agnew, J. (1998). The impossible capital: Monumental Rome under liberal and fascist regimes, 1870-1943. Geografiska Annaler: Series B., Human Geography, 229-240.

Algreen-Ussing, G., Beck, L., Frandsen, S. B., & Hansen, J. S. (2000). Urban Space and Urban Conservation as an Aesthetic Problem: Lectures presented at the international conference

in Rome 23rd-26th October 1997. Rome: Lerma di Bretschneider.

Archibugi, F. (2005).Rome: A New Planning Strategy. London: Routledge.

Basile, O., Persa, L., & Usami, D. S. (2010). A methodology to assess pedestrian crossing . European Transportation Res. Rev, 129-137.

Bassett, D. R., Pucher, J., Buehler, R., Thompson, D. L., & Crouter, S. E. (2008). Walking, Cycling, and obesity Rates in Europe, North America, and Australia. Journal of Physical Activity

and Health, 795-814.

Crankshaw, N. (2008). Creating Vibrant Public Spaces: Streetscape Design in Commercial and Historic Districts . Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Gori, S., Nigro, M., & Petrelli, M. (2012). The impact of land use characteristics for sustainable mobility: the case study of Rome. European Transportation Review, 1-14.

Harder, B. (2007). Weighing in on City Planning. Science News, 43-45.

Jacobs, A. B. (1993). Great Streets. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Leitner, T, Hoeglinger, S., Yannis, G., Evegnikos, P., Bos, N,. Reurings, M., Broughton, J., Lawton, B., Walter, L., Andreu, M., Pace, J., & Sanmartin, J. (2008). Traffic Safety Basic Facts

2008: Pedestrians.European Road Safety Observatory.

Lenzi, L. (1931). The New Rome. The Town Planning Review, 145-162.

Lynch, K. (1960). The Image of the City. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bibliography

-

7/31/2019 Walk Ability May 2012

47/47

Minesi, G., ed. Translated by D. Borri and Ilene Steingut. (2001). Urbanistica, 217-286.

Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS). (2002, December). Retrieved May 3, 2012, from Active Living Research: http://www.activelivingresearch.org/files/NEWS_

Survey_0.pdf

Real Time Rome. Retrieved 3 May, 2012, from Massachusetts Institute of Technology SENSEable City Lab: http://senseable.mit.edu/realtimerome/

Reid, S. (n.d.). Pedestrian Environments: A Systematic Review Process. Retrieved May 3, 2012, from Walk 21: http://www.walk21.com/papers/Reid.pdf

Roma, P. d. (n.d.). The Via Prenestina: The Mountain Route to the South. Retrieved May 3, 2012, from Tesori: Intorno a Roma: http://en.tesorintornoroma.it/Itineraries/The-Via-Prenestina

Sepe, M. (2009). PlaceMaker Method: Planning Walkability by Mapping Place Identity. Journal of Urban Design, 463-487.

Southworth, M. (2005). Designing the Walkable City.Journal of Urban Planning, 246-358.

La Storia dellAcquario Romano. Retreived May 6, 2012, from Casa dellArchitettura: http://www.casadellarchitettura.it/stampa/storia.html

Vanderbilt, T. (2012, April 13). Americas Pedestrian Problem. Slate.

Wood, J. & Hughes, J. eds. (2012, April 19). Pedestrian and Walkability Research. Retrieved May 3, 2012, from Reconnecting America: http://reconnectingamerica.org/news-center/

half-mile-circles/2012/pedestrian-and-walkability-research/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+Half-mileCirclesArticles+%28Half-

Mile+Circles+Articles%29&utm_content=Google+Reader

Zeynep, C., Favro D., & Ingersoll, S. (1994). Streets: Critical Perspectives on Public Space. Berkeley: University of California Press.