3 things you need to now about people and technology - J. Verhaegen

Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

-

Upload

gabriela-ferreira -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 1/14

Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456

Costs and benefits for farmers participating in innovative marketingchannels for quality food products

Ingrid Verhaegen, Guido Van Huylenbroeck*

Department of Agricultural Economics, Ghent Uni versity, Coupure Links 653, 9000 Gent, Bel gium

Abstract

The extra benefits and costs for farmers participating in six innovative marketing channels for quality products in Belgium are

analysed. A theoretical model serves as an analytical device to structure the qualitative comparisons with the common marketing

channel and with direct sale. The analysis is mainly qualitative, because many benefits and costs cannot be quantified exactly. In theanalysis, transaction costs are explicitly taken into account because they constitute a real cost when switching from a common to an

innovative marketing channel. In all six marketing channels, higher costs are compensated for by higher revenues due to higher

prices and a higher turnover and by reduced uncertainty. These factors encourage farmers to enter quality food projects. In addition,

we found that co-operation decreases transaction costs and that collective initiatives enable farmers to enter the pathway of quality

food production without investing excessive labour or capital. r 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the Belgian food market has been

characterised by an increased production of processed

farm products, labelled and regional products, oftencombined with the development of new marketing

channels. There are several reasons for this. Farmers

are looking for new sources of income as prices decrease

and all kinds of regulations (European, federal and

regional) impose production limits. In addition, con-

sumers demand better food quality and safety, ecologi-

cal agriculture and regional products. While some

farmers produce and sell farm processed food products

individually, others develop collective marketing chan-

nels to sell quality food products. Since the relative risks

and benefits of participating in these collective market-

ing channels are unclear, we examined the economic

incentives for farmers to participate in these emerging

collective quality food marketing channels. After

describing the context in which these initiatives are

emerging, a theoretical model is used to calculate the

costs and benefits to the farmers.

The theoretical framework is applied on six emerging

marketing channels which have been the subject of a

wider analysis. These six initiatives give a good picture

of the variety of initiatives presented in a 1996 inventory

of initiatives in Belgium (Van Huylenbroeck et al.,

1998). They are: Farmers’ Markets and Foodteams, two

local initiatives that centralise direct selling activities

of several farmers in space and time; Produits deQualit!ee d’Autrefois (ProQA) and Fruitnet, who

manage a marketing channel with labelled products

(beef for ProQA and pip-fruit for Fruitnet); and finally

Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain, two co-operatives

involved in the marketing of fresh and processed farm

products that have developed a common processing

plant for, respectively, cheese and meat products. These

initiatives are described in more detail in Appendix B.

On the basis of the analyses of these six initiatives some

conclusions are formulated.

2. Context in which collective marketing channels emerge

The creation of marketing channels selling quality

farm products is certainly not new. In southern

countries such as Italy and France with their rich

gastronomic traditions and diversity of local products,

such commercialisation chains have always existed (see

e.g. Fanfani et al., 1996; Brasili et al., 1998; Arfini and

Mora, 1998; Bessiere, 1998). In these quality food

channels, direct communication between producers and

consumers is of paramount importance to ensure that

quality is paid for. In the last decade, however, they

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Van Huy-

lenbroeck).

0743-0167/01/$ - see front matter r 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 7 4 3 - 0 1 6 7 ( 0 1 ) 0 0 0 1 7 - 1

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 2/14

have emerged in all industrialised countries, where they

are promoted as a possible model to respond to the

actual problems faced by agriculture (Hinrichs, 2000).

Battershill and Gilg (1998a) and Grey (2000) present

them as a possible alternative to the industrialised food

market. Without being exhaustive, the emergence of

such ‘alternative’ channels is also described by Nygardand Storstadt (1998), Festing (1998), Chubb (1998),

Fonte (1999), Feenstra (1997), Feensta and Lewis

(1999), Barberis (1999), Westgren (1999), Ilbery and

co-workers (Ilbery and Kneafsey, 1998, 2000; Ilbery

et al., 2000) and many others. As indicated, this paper is

based on research on such alternative channels in

Belgium. More details on the research can be found in

Mormont and Van Huylenbroeck (2001).

The problems and challenges faced by industrialised

agriculture today are multiple. First, there is a produc-

tion challenge: the ‘‘productivist’’ model of the past,

promoted and supported by EU-policy, has touched

upon the limits of its own success. Because of thebudgetary implications and the international competi-

tion, a model based on a further increase of the

productivity and efficiency will result in a further

reduction of the agricultural population. In addition,

environmental issues preclude a further increase of the

production in several European regions. Consequently,

the income of progressively more farmers will margin-

alise. According to recent statistics of the Belgian

National Institute of Statistics, about 22% of profes-

sional farms in Flanders have an economic dimension

(measured in European Standard Units) which is too

low to survive if they cannot create additional addedvalue. The concentration of production in some areas

and the need to increase efficiency also leads to further

normalisation and standardisation of the production.

This inevitably leads to a reduction in the diversity of

available commodities and an increase in sanitary and

other risks.

Second, there is a demand problem: with increased

purchasing power and under pressure of recent food

scandals, new consumer demands with respect to food

have emerged. Today, a demand for low cost food co-

exists with an increased interest in quality foods and

certainly with a demand for food safety. Third,

standardisation of production practices leads to social

marginalisation (less farmers in rural areas) and to loss

of rural identity, bio-diversity and landscapes. This,

paradoxically, happens at a time when increased

purchasing power increases the demand for environ-

ment-friendly goods and services, rural tourism and

recreation. These phenomena indicate that there is a

problem of externalities (both positive and negative) not

remunerated by the agro-industrial markets.

In this context, a number of rural actors (farmers, but

also consumers and local citizens), have been searching

for new production and marketing models for quality

foods in an attempt to reconcile the interests of

producers (creating added value), consumers (food

quality and health) and citizens (environmental and

local development concerns). Bowbrick (1992) Batters-

hill and Gilg (1998b) and Ilbery and Kneafsey (2000)

recognise that quality construction is a complex process.

Marsden and Arce (1995) indicate that quality is a socialconstruction. Murdoch et al. (2000) emphasise the link

with the nature and local embeddedness of supply

chains. Feenstra (1997) stresses ecological soundness,

social equity, and democracy as important issues while

Holloway and Kneafsey (2000) emphasise ecological,

ethical and community awareness as important elements

for consumers at farmers’ markets. A number of French

authors such as de Sainte-Marie et al. (1995) de Sainte-

Marie and Valceschini (1996), Lassaut and Sylvander

(1998), Raynaud and Valceschini (1997) and Valceschini

and Maze (2000) also emphasise the importance of non-

tangible aspects of quality.

Since conventional marketing channels are based onindustrial co-ordination, quality efforts that are not

reflected in tangible features of the product are not

financially rewarded. Therefore, there is a need for new

organisational models for production and distribution

channels that promote and reward non-tangible quality

characteristics and that compensate farmers for extra

efforts and costs. The central focus of this paper is to

analyse how well the innovative marketing channels that

we mentioned before have succeeded in this objective

and whether or not they have been able to create enough

added value for the participating farmers.

That innovative marketing channels create enoughadded value to financially reward participating farmers

is not as obvious as it might seem: not only do the

required changes in production practices create higher

costs, but so does setting up of a new marketing channel.

In innovative production and marketing channels farm-

ers often take over such market functions as packaging,

transport, selling and sometimes even processing and

transformation. In addition, establishing a market

channel also creates some extra costs which in literature

are commonly identified as ‘‘transaction costs’’ (Hobbs,

1995). These are costs associated with the organisation

of the transaction between different partners. They

consist of (1) information costs to get the necessary

knowledge to be able to produce and to sell the good; (2)

negotiation costs to get an agreement with the transac-

tion partner; and (3) control costs to be sure that an

agreement is respected. A production and marketing

channel should be organised in such a way that total

transaction costs are minimised. Hobbs and Young

(1999) argue that transaction costs are a function of

transaction characteristics; the latter are the result of

product and production characteristics which in turn are

influenced in a dynamic perspective by prevailing

consumer preferences, available technologies and exist-

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456444

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 3/14

ing regulations. From this perspective, old production

and marketing channels are only replaced by new ones

when transaction costs can be reduced.

As we have shown before (Verhaegen and Van

Huylenbroeck, 2001), appropriate governance and

organisation of the channel can significantly reduce the

general transaction costs of the channel. However, froma farmer’s perspective, the most important issue is to

analyse the changes in the private transaction costs. This

discussion is not unlike the one with respect to

participation in agri-environmental measures (Falconer,

2000). Holleran et al. (1999) indicate that collective

quality assurance systems have the potential to reduce

transaction costs, and therefore could be an incentive

for entering such schemes. We therefore hypothesise

that innovation will only take place if the organisation

of the channel sufficiently reduces private transaction

costs. In addition, we hypothesise that co-ordinated

governance can do this more effectively than pure

market governance in most cases.Transaction costs are mainly assessed in a qualitative

and comparative manner, because a lot of the private

costs linked to the choice of a marketing channel can

hardly be estimated or valued. In a qualitative assess-

ment, the point of reference is important. In this article,

two comparisons are made: (1) between the innovative

marketing channel and the conventional (anonymous)

marketing channel that is not remunerating the specific

product characteristics linked to the changes in produc-

tion practices, and (2) between the innovative marketing

channel and the individual sales of farm (processed)

products at the farm, with the latter having theadvantage of direct contact with consumers, but the

disadvantage is that the individual farmer incurs all the

costs. Both these comparisons are made because these

seem to be the two major alternative outlets for farmers

wanting to sell ‘‘specific’’ products.

3. A theoretical model for the cost–benefit analysis of

marketing channels

To explain the economic reasons why farmers leave

one ‘‘old’’ marketing channel for a ‘‘new’’ marketing

channel, a comparative cost–benefit analysis is neces-

sary. Costs and benefits for the farmer in the ‘‘new’’

(innovative) marketing channel are compared with the

costs and benefits in the ‘‘old’’ marketing channel. While

for most farmers the old channel is the common

marketing channel,1 for some farmers it is the individual

direct sale of farm products. Our analysis follows the

transaction cost economic framework (see Williamson,

1996) in the sense that besides direct production and

commercialisation costs, private transaction costs are

taken into account as well. Transaction costs have been

defined before as costs associated with setting up a

business activity or the exchange of commodities(Hobbs, 1995).

When taking the transaction costs into account, the

following general model can be used as a basis for

comparative cost–benefit analysis:

DP ¼ DPQ DrI DTC; ð1Þ

where D is the difference between the two marketing

channels, P the profit; P the price; Q the quantity; r the

remuneration of the inputs; I the quantity of inputs used

and TC the transaction costs.

In a marketing channel with producer (p), middleman

(m) and salesman (s) the profit functions for the actors

involved arePp ¼ PpQp rpI p TCp; ð2Þ

Pm ¼ PmQm PpQp rmI m TCm; ð3Þ

Ps ¼ PsQs PmQm rsI s TCs: ð4Þ

The profit (P) is the difference between revenues and

costs. The revenues depend on the price (P) and the

quantity (Q) sold. The costs are threefold: (1) purchas-

ing costs of the basic product for actors further in the

chain; (2) costs for the use of inputs (I ) that have to be

paid a remuneration (r); and (3) transaction costs (TC).

The profit of the total marketing channel is the sum of the profits of all actors in the channel: the revenues of

the salesman less the costs of the resources used by

producer, middleman and salesman and less the

transaction costs of producer, middleman and salesman

(see Appendix A.1).

The addition of costs and revenues for each actor

allows to assess the total relative profitability of a new

marketing channel (e.g., the initiative) in comparison

with an ‘‘old’’ one (e.g., the common marketing

channel). When examining the costs and benefits for

individual farmers in entering an innovative marketing

channel, the difference in profitability DP for the

indi vidual actor is of importance.

Both total and individual levels of analysis are of

interest. Imagine e.g. an initiative that has registered a

(regional) label based on a code of practice for the

participating farmers. The farmers sell the labelled

products through a traditional marketing channel with

producer, middleman and salesman. Suppose that

middleman and salesman use the same resources as in

the common marketing channel (without label) with

which the labelled marketing channel is compared.

Simple calculus (see Appendix A.2) is sufficient to see

that in this case the profitability of the labelled marketing

1The common marketing channel of fruit and vegetables consists of

producers, auctions, wholesalers and retailers. For livestock and meat,

the common marketing channel involves the producer, the livestock

merchant and/or the auction, the slaughterhouse and the butcher. The

milk of the dairy farmer passes through the milk factory, the

wholesaler and the retailer in the common marketing channel.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456 445

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 4/14

channel depends on the net difference between the extra

revenues at the level of the salesman, the extra

production costs of the producers and the difference in

transaction costs for all actors involved. These extra

transaction costs can take the form of contributions to

an organisation controlling the label, but also of

marketing costs to inform consumers about the label,the learning costs of actors to get acquainted with the

new practices and so on.

At the level of the actors, the new marketing channel

has to compensate not only for the higher direct costs,

but also for possibly increased private transaction costs.

That private transaction costs are important can be

shown by a second example. Imagine a farmer who

decides to sell his products directly to the consumer. The

farmer himself has to take over the marketing function

of middleman and salesman. Suppose further that the

farmer has the same revenues as the salesman in the

common marketing channel (Pp1Qp1 ¼ Ps2Qs2). It fol-

lows (see Appendix A.3) that only when the farmer canreduce commercialisation and transaction costs, direct

sale has a positive profitability in comparison with the

common marketing channel. In the case of Farmers’

Markets e.g. where prices are below that of the salesman

(the retailer), the organisation must already generate a

substantial decrease of the commercialisation and

transaction costs for the farmer in order to make the

chain profitable.

Both examples show that total and individual profit-

ability are closely linked. On the one hand, the

organisation of the production and marketing channel

has to be such that individual costs can be decreasedsufficiently in comparison with the benefits realised; on

the other, all costs within the chain must be paid for,

including the transaction costs covered by the inter-

mediate organisation. If the intermediate organisation is

not supported by public funding (e.g. because they

deliver public goods), the new channels will have to

recuperate these costs either by increasing consumer

prices (and thus weakening their market position) or by

asking higher membership or participation fees of

farmers. For these reasons, studying the profitability

for participating farmers provides indirect evidence for

the possibility of recuperating costs by farmers’ con-

tributions and therefore gives insight into the economic

possibilities of the new channels. In the remainder of this

paper we therefore focus on the relative profitability of

the new marketing channels for participating farmers.

4. Cost–benefit analysis of six innovative marketing

channels

As mentioned before, six innovative and emerging

marketing channels have been studied in detail. Briefly,

with Farmers’ Markets and Foodteams, farmers sell

their products directly to the consumer on an organised

basis, either on weekly markets or through a local

consumer organisation. ProQA and Fruitnet, are

labelled, but in terms of intermediates, traditionally

build marketing channels. The former sells meat under

the Blanc Bleu Fermier (BBF) label, while the latter sells

pip-fruit, produced according to integrated productionmethods, under the Fruitnet label. Fermi"eere de M!eean

and Coprosain have been founded by farmers with the

assistance of a few consumers. These co-operatives

produce cheese (Fermi"eere de M!eean) or meat products

(Coprosain) that are commercialised with other non-

processed and processed farm products at different

public markets, in own outlets and directly to whole-

salers, retailers or caterers.

The cost–benefit analysis weighs the differences in

revenues, production costs and transaction costs for the

farmers between the use of the former versus the new

marketing channel (‘‘the initiative’’) as outlet for specific

quality products. For livestock holders (ProQA andCoprosain), dairy farmers (Fermi"eere de M!eean), and fruit

and vegetable growers (Fruitnet, Farmers’ Markets and

Foodteams), the new marketing channel is an alternative

to the common marketing channel. However, for many

of those farmers selling through Farmers’ Markets,

Foodteams, Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain, the

alternative is to sell their products directly to the

consumers on an individual basis. For these initiatives,

an additional comparison is made between the new

marketing channel and the individual direct sale of farm

products.

We do not measure absolute profitability of the newmarketing channels because this would require more

detailed information on incomes; also, in many cases it

is impossible to exactly evaluate or measure transaction

costs (such as e.g., the costs to acquire necessary skills

and information). Therefore, only their relati ve profit-

ability is compared with an alternative outlet for the

commodities produced. The advantage of a relative

comparison is that differences in (transaction) costs need

not be quantified exactly. The differences only have to

be identified and described: getting an idea of their

development in time is enough. The disadvantage is of

course that our analysis does not allow to indicate the

absolute profitability of new marketing channels, which

may be important, e.g. to evaluate the possibilities of the

new marketing channels as a survival strategy for

marginal farmers.

The information for our analyses has mainly been

collected through in-depth interviews with the different

actors involved in the new marketing channels. In

these interviews, the marketing channels were compared

with regard to revenues, production costs and transac-

tion costs. In addition, economic and financial informa-

tion was gathered from the organisations of the

initiatives.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456446

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 5/14

4.1. Comparison with the common marketing channel

In the first cost–benefit analysis, the situation of the

farmers is compared with the common marketing

channel as reference. The results are presented in Table

1. The first row presents the products for which the

analysis is made. Revenues, production costs andtransaction costs generated by the initiative can be

higher (+), lower () or similar (=) in comparison with

those in the common marketing channel. Finally,

changes in uncertainty about prices and quantities sold

are determined. All the data in this table are based on

facts reported in monographs for each case study

(Verhaegen and Van Huylenbroeck, 1999c). The reasons

for assigning a qualifier (+, , =) are discussed in the

following sections.

4.1.1. Revenues

For the same product, farmers get higher revenues inall initiatives in comparison with the same product in the

common marketing channel. This is mainly due to

hi gher prices in the initiatives. This is not surprising: not

only is obtaining higher prices for quality products a

major objective of these alternative marketing channels,

the higher prices are also the most important reason

quoted by farmers to participate in the initiative. Morris

and Young (2000) also mention this as one of the main

motives for farmers to introduce Quality Assurance

Schemes in UK agro-food production.

In most of the initiatives, the contracts, agreements

and arrangements either explicitly mention a higher

price compared with the market price or mention it

implicitly by using words as ‘‘reasonable’’, ‘‘good’’ or

‘‘fair price’’.2 Fruitnet fixes the price of apples at a price

that is 0.02–0.05 EUR per kg higher than the market

price. Fermi"eere de M!eean pays 0.01 EUR more for a litre

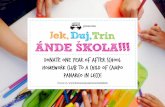

of raw milk than the dairy factory. Fig. 1 illustrates the

higher price farmers get in the co-operative Coprosain:

the lowest prices for bulls paid by Coprosain are

compared with the highest market prices at that

moment. Other examples of price comparisons are given

in Verhaegen and Van Huylenbroeck (1999a, b).

Many farmers emphasise a second source of higher

revenues, namely the good price they get for productsclassified as ‘‘second class’’ under industrialised market

co-ordination. In the common marketing channel, these

products are sanctioned rather hard by a substantial

price difference compared with ‘‘first quality’’ products.

In markets based on domestic co-ordination, this can

often be avoided. For example, livestock producers of

ProQA can sell all their cattle (high or low quality)

through the co-operative at a price higher than market

prices. Another example is that of a fruit producer at the

Farmers’ Market who manages to sell pears with hail

damage (small brown spots) at the price of first quality

pears because the direct contacts with his clients allow

him to explain the reasons for the brown spots,

convincing them on the basis of taste of the intrinsicquality of the pears. This is not possible when selling

through the auctions (the common marketing channel)

where hail damage results in a significant decrease in

quality class and consequently in price. Battershill and

Gilg (1998b) also argue that direct selling has the highest

potential for valuing low-intensive farm practices:

farmers can ask the maximum appropriate price in

return for giving complete information about products,

production and farming methods.

Quantities sold per unit area and/or time period are

comparable between both marketing channels. A small

difference is mentioned by farmers at Farmers’ Markets,

Foodteams, Coprosain and Fruitnet. For the farmers atFarmers’ Markets and Foodteams these quantities are

slightly less because they have to diversify their

production in varieties and in time (e.g. because they

have to have lettuce the whole season). This results in a

slightly lower production than in the case of specialised

seasonal production. In the case of Coprosain, a code of

practice limits the number of animals per square meter

and the age at which the animals are sold (older than in

the common marketing channel). But for both groups

the minor decrease in quantity is fully compensated for

by higher prices.

The integrated production method for pip-fruit resultsin a lower productivity of the orchard due to slightly

higher losses due to pest damages, but the difference is

very small (maximum 10%). The main reason for the

lower production volume of the Fruitnet farmers is the

code of practice of the Fruitnet label which imposes an

extensive orchard structure with a one-row system (thus

lesser trees per hectare) instead of the double-row tree

system commonly used in non-integrated pip-fruit

orchards. But this decreased production is partly

compensated for by the higher percentage of the

production that is classified as ‘‘high quality fruits’’

and thus may use the Fruitnet label.

4.1.2. Direct costs

In the new marketing channels, operational costs in

general are slightly higher than in the common market-

ing channels. The code of practice followed by beef

producers of ProQA and the dairy practices imposed by

Fermi"eere de M!eean do not generate a substantial increase

in the production costs for the farmers. On the other

hand, higher labour costs slightly increase production

costs for pip-fruit producers using the integrated

production practices of Fruitnet. In the Coprosain

marketing channel, the increased production costs are

2These expressions imply that the actual market price is not

considered to be a reasonable price for the average farmer in the sense

that the market price does not reward all the production factors used,

including farm labour.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456 447

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 6/14

caused by the code of practice (animals have to lie on

straw, may only be fed with feed produced at the farm

or in the region, and the fattening period has to be

longer).

With ProQA, Fruitnet and Fermi"eere de M!eean the

direct commercialisation costs3 are similar to those in the

common marketing channels. In Coprosain, farmers

have some extra commercialisation costs such as the

costs for transporting the animals to the slaughterhouse.

While in the common marketing channel these trans-

portation costs are paid for by the cattle merchant,

Coprosain farmers have to pay for it themselves. The

direct sales activity of the farmers selling through

Farmers’ Markets or Foodteams involves transport,

stallage, a license for sale activities, market stall, etc. In

addition, products have to be divided and packed in

smaller quantities in the right packaging material. These

factors all significantly increase commercialisation costs

as compared to a common channel where products are

sold in bulk. Vegetable producers for example weekly

deliver vegetable baskets (an assortment of vegetables of

the season for 1 week cooking) to Foodteams. As

these vegetables are delivered in a plastic bin owned by

the farmers, commercialisation costs are increasedbecause the bins used in the auction are the property

of the auctions which the farmers can hire or even use

for free.

4.1.3. Transaction costs

With respect to information and negotiation costs, a

distinction has to be made between transaction costs

linked to the selling activity or linked to the acquisition

of the necessary production and marketing skills. With

respect to the negotiation costs linked to the selling

acti vity, a decrease of the information and negotiation

costs is only realised in the meat channels (ProQA and

Coprosain). In the common marketing channel for beef,

farmers need to contact several cattle merchants before

an agreement can be reached with any of them. In order

to be able to negotiate a good price, the farmer has to

remain well informed about market conditions and

prices. Since livestock producers of ProQA and Copro-

sain have made agreements with the co-operative on

quality and quantity standards, price standards and on

an agenda to sell, a substantial decrease of the

information and negotiation costs is realised in this

group. In the common market channel, the producer has

to spend at least half a day to find a cattle merchant for

Table 1

Comparative cost–benefit analysis of the new marketing channel and the common marketing channel (with the common marketing channel being the

reference)a

Farmers Farmers’ markets Food-teams ProQA Fruitnet Fermiere de Mean Coprosain

Product Fruit and vegetables Fruit and vegetables Beef Pip-fruit Milk Beef and pork

Revenues

Price + + + + + +Quantity =() =() = = =()

Direct costs

Production =(+) =(+) = =(+) = +

Commericialisation + + = = = +

Transaction costs

Market information + + =

Negotiation + + = (+)

Human skills

Control (+) (+) = + = =

Contribution + + + + + +

Uncertainty

Price

Quantity sold (+) (+) ()

aNote: The signs indicate the direction of the changes in revenues, costs and uncertainty: +: increase; : decrease; =: similar; ( ): minor changes.

Fig. 1. Comparison between minimum liveweight prices for bulls paid

by Coprosain and maximum prices at the market of Anderlecht during

1996 and 1997.

3The direct commercialisation costs are the costs incurred by

preparing the products for sale and include cleaning, packaging,

storage and transport.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456448

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 7/14

every animal ready for slaughtering, while this is

reduced to half a day or one evening every 3–4 months

(regardless of the number of animals fattened) in the

new marketing channel.

In the common marketing channel for fruit and

vegetables, the negotiation and information costs are

already minimised by the development of the co-operative auctions. Here the initiatives cannot realise

an economy. The same is true for the farmers delivering

milk to the milk factory in the common marketing

channel. It follows that when these farmers get more

involved in the marketing of their products, the

information and negotiation costs rise. However, given

the price and delivery system agreed upon, this increase

is only minor for the milk producers of Fermi"eere de

M!eean. At Farmers’ Markets prices are fixed between

auction prices and retail prices each market-day before

the market starts. This means that farmers have to

gather price information from auctions and retailers in

the neighbourhood. Extra negotiation costs for thesefarmers lie in the quarter of an hour spent every week at

the beginning of the market to negotiate prices in the

price commission, which every farmer selling at the

market has to attend. Farmers delivering through

Foodteams also have to gather extra information about

prices and products (e.g., recipes) and have to negotiate

regularly about prices and quality expectations with the

consumers.

An important aspect of collective initiatives is the

economy in learning costs that can be realised. An

example of this is Fruitnet. The mother organisation of

Fruitnet, GAWI, has acquired specialised knowledgeabout integrated production methods for pip-fruit which

is distributed via the organisation. The Fruitnet farmers

benefit from this by having easier access to this

information than if they should have to collect the same

information under market conditions. Fruitnet also

collects market information and distributes this under

his members. Also in the other initiatives studied, the

learning dimension and investment in human capital

should not be neglected. Farmers participating in the

initiatives can economise on the investment in human

capital which is necessary to realise the innovation. High

economies are realised on private transaction costs

because farmers themselves have to invest less in the

development and acquisition of skills related to the

production practices applied, the transformation pro-

cesses, the legal aspects of market organisation and so

on. The more efficient the flow of information in an

organisation, the more private transaction costs related

to collecting information and acquiring the necessary

skills can be reduced.

How the initiatives have been able to build up the

necessary skills for successful innovation is not the

subject of this article (for more details see Stassart and

Collet, 1999). One of the problems is certainly how

access to this intellectual property can be regulated and

protected, in particular because a lot of the knowledge is

collective and public (e.g. the knowledge on integrated

pest management). Besides providing legal protection of

a collective label or brand name and the detailed

requirements stipulated in the code of practice, organi-

sations also try to increase the specificity of theknowledge in order to make acquisition of or access to

this knowledge outside the organisation more difficult

and expensive. By increasing the service to the partici-

pating farmers the free rider problem is prevented. A few

good examples of this are: (1) market commissioners

taking care of practical details in Farmers’ Markets; (2)

a central organisation searches for new teams and

provides information about sustainable production

techniques in Foodteams; (3) extension is individualised

in GAWI/Fruitnet; (4) information is exchanged on

feeding in the beef channels. The more specific and

complex the innovation, the more difficult it becomes for

others to copy it.Depending on the degree of protection needed and

desired, contractual relationships will differ. For Farm-

ers’ Markets for example an agreement with the village

authorities is sufficient to prevent a similar initiative

from being started in the neighbourhood. Further,

market access is restricted in order to prevent too much

competition between farmers selling the same product.

This is done by allowing new members access only when

all existing members agree to it. In Foodteams, the

central organisation is responsible for the selection of

farmers, giving it a certain executive power because it

can prevent farmers from delivering to new teams if theydo not obey the rules. The main asset of Fruitnet is an

exclusivity contract with one of the biggest distribution

channels in Belgium. Consequently, integrated fruits

sold outside the Fruitnet contract form a kind of rest

market. But the organisation is aware of the fact that

with an increasing demand for integrated pip-fruit, the

value of this asset is decreasing and is therefore actually

studying how it can increase the specificity of the code of

practice. ProQA (which is operating under the non-

exclusive public BBF label) is also working with long-

term contracts with butchers to ensure its market share,

and is making some attempts to develop an own, more

specific label.

In the case of transformed products, the main asset is

the knowledge about the transformation and the

processing activity which is often in the hands of one

or a few persons. To protect themselves against the

hold-up problem, these organisations are offering these

key-persons a share in the overall profit. Giving services

to farmers, running the organisation as well as protect-

ing the property rights all incur costs to the organisation

that have to the recovered. But the higher the savings on

private transaction cost are, the more the farmers are

willing to pay for it to their organisations.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456 449

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 8/14

Another kind of transaction costs are the control costs

caused by the necessity of setting up a control system to

guarantee the quality of the product and the observance

of the code of practice. Important differences exist

between the initiatives. Farmers’ Markets and Food-

teams depend on an informal control system in which

market commissioners or consumers regularly visit thefarm to check whether only self-produced products are

sold and whether the production methods are in

accordance with the statements of the farmers. The

control costs to farmers in these systems are low.4

Fruitnet farmers, on the other hand, bear significant

control costs because they have to subscribe both to an

organisation controlling the official code of practice

regulating integrated pip-fruit production as well as to

the special control on the Fruitnet code of practice

containing some extra regulations. In the year 2000, the

yearly contribution was anywhere between 400 EUR for

farms smaller than 5 ha and 1000 EUR for farms larger

than 40 ha. Farmers of ProQA and Coprosain are alsocontrolled by a control agency, but these control costs

are paid for by the co-operatives. Consequently, the

private control costs are of the same magnitude as those

of the common marketing channel. The farmers of

Fermi"eere de M!eean also have no extra control costs

because they still deliver part of their milk to the milk

factory where it is tested. Further, the employees of

Fermi"eere de M!eean control the quality of the milk during

the cheese making process, but this is informal and does

not represent an extra cost.

The last category of costs includes the contributions

farmers have to pay to the organisation in the form of yearly membership fees or one time capital participa-

tions. As already mentioned, these contributions or

participations can be classified as a transaction cost

because (1) they allow access to the information and

market of the initiatives and (2) the organisation covers

many transaction costs farmers would have to pay for

themselves under market conditions. In general, the

contributions are rather modest: approximately 30 EUR

per year at Farmers’ Markets, 125 EUR per year to

become a member of Fruitnet and 3% of the turnover at

Foodteams. The entrance fee in Fermi"eere de M!eean is

approximately 375 EUR; the older members have each

invested approximately 745 EUR. At ProQA, farmers

have a participation in the co-operative of approxi-

mately 1250 EUR. Not every farmer that delivers

products to the co-operative Coprosain has to be a

member of the co-operative, but those who are each

have contributed at least 2500 EUR and participate in

the benefits of the co-operative. Besides these direct fees

or contributions, the organisations (with the exception

of Farmers’ Markets and Foodteams who never become

owners of the products) also take a certain margin on

the sales to cover their costs. With the exception of

farmers working with Foodteams, farmers do not feel

that these fees are excessive. This may indicate that the

savings on the private transaction cost and/or the extrabenefits supercede the entrance costs. For Foodteams,

the reluctance of farmers to pay the contribution can be

explained by the low specificity of the services. After the

contacts with the local teams have been established,

farmers do not perceive to receive any further benefits of

the central organisation.

4.1.4. Uncertainty

Besides costs and benefits, the uncertainty about

prices and sales volumes also needs to be compared

between two marketing channels. Bates et al. (1996)

called the trade-off between costs and risk the most

important consideration when comparing the costs of one marketing method with another.

In most of the initiatives, the surplus price is

guaranteed in the regulations of the initiative. This

reduces price uncertainty when using the new marketing

channels compared with the sometimes volatile market

situation outside the channel. This price certainty is

accentuated by the fact that most initiatives try to reach

stable prices, based on a calculation of real production

costs. Fruitnet e.g., is encouraged to do this by a

supermarket chain (main buyer of Fruitnet fruit) who

itself strives for fair but stable consumer prices. In most

Foodteams, producers and consumers negotiate a yearlyprice that is only renegotiated if (market) conditions

change drastically. Although at Farmers’ Markets prices

do follow common market prices, wide swings are

attenuated, resulting in a smaller price variation

interval. An important benefit of better price security

is that farmers can better estimate their revenues for a

given period, making investments in e.g. environmen-

tally sound practices less risky. This can be particularly

important for innovative technologies.

With respect to quantities, ProQA, Fermi"eere de M!eean

and Coprosain give participating farmers an informal

take-off guarantee. Within Fruitnet, the original mem-

bers have a first selling right. Only in case of higher

demand by the main buyer (a large supermarket), other

integrated fruit producers are also allowed to deliver. On

Farmers’ Markets and within Foodteams no implicit

guarantee is given, but uncertainty is small because most

farmers are also selling through the common marketing

channel, meaning that the surplus of the market day can

always be sold, be it at a lower price.

4.1.5. Global analysis

Although comparative qualitative analysis does not

allow one to evaluate absolute profitability, and even

4As some of the farmers at Farmers’ Markets and Foodteams make

use of a label (Fruitnet or Biogarantie (=an organic production)

label), they incur significant control costs equal to those discussed for

the Fruitnet farmers.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456450

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 9/14

though the result will depend on the magnitude and

relative importance of the different cost items, the

overall picture can be regarded as positive. This is also

the general impression of participating farmers, who

consider the extra revenues to be sufficient to compen-

sate for the increase in direct (production and commer-

cialisation) and transaction costs.However, we agree with Festing (1997) that some

caveats are in order. First, there is a danger for farmers

to overestimate extra revenues generated and to under-

estimate the extra costs, and in particular the transac-

tion costs because these are not always expressed

(directly) in monetary terms. For example, farmers

delivering to Coprosain do not value the time devoted to

meetings in which production and sales are planned.

Second, it is not always possible to generalise these

general impressions because most farmers participating

in initiatives already had a production method or

management practice resembling the one needed to

enter the initiative. This means that their adaptationcosts to make the necessary changes were small or

negligible, a finding which may not be the case for other

farmers. If major changes were to be needed, the cost/

benefit calculation may be different. For example,

farmers switching to integrated pip-fruit production

have to weigh the balance between the costs avoided

(such as preventive treatments with chemical sprays) and

new costs (such as pest follow-up, more infected fruits).

A third remark is that initiatives like Farmers’ Markets

and Foodteams (where farmers are taking over (part of)

the marketing function of wholesalers and retailers) will

only be profitable for farmers with an excess (and thuslow opportunity cost) of labour. In case of shortage of

labour, the marketing activity comes in competition

with the production activity (in quality or in quantity).

This is corroborated by many farmers who stated that

their activity is only profitable because they can use

relatively cheap family labourFhiring people for the

commercialisation activity would be too expensive.

4.2. Comparison with indi vidual direct sale of farm

products

As already indicated, many of the farmers involved

were already engaged in selling farm products (fresh and

processed) directly to the consumer. In most cases, these

farm products are sold at the farmer’s own farm shop,

but sometimes farmers sell their products at public

markets and yet others sell them through local retailers.

The question then is whether the sale of farm products

through organised marketing channels such as Farmers’

Markets, Foodteams, Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain

has any advantages in comparison with the individual sel-

ling of farm products directly to the consumers. The

result of this comparative analysis is presented in Table 2.Three groups of farmers have been distinguished in

the analysis: (1) farmers selling fresh farm products

(fruit and vegetables, flowers) or processed farm

products (yoghurt, ice-cream, cheese, bread, jam, juice,

meat products, etc.) at Farmers’ Markets or Foodteams;

(2) suppliers of processed farm products to Fermi"eere de

M!eean and Coprosain; and (3) farmers who now sell their

milk, cattle or pigs to the co-operatives but who would

otherwise have to invest in equipment to produce their

own cheese or meat products. Although the signs of the

changes in revenues or costs are quite similar for the

three groups, the explanation for each one of them isdifferent, and will be discussed in the following sections.

Other issues have already been discussed in Section 4.1,

and will therefore only be mentioned briefly.

Table 2

Comparative analysis of the new marketing channel and the individual direct sale (with the individual direct sale being the reference)a

Farmers Farmers’ markets and foodteams Fermiere de Mean and Coprosain

Product Fresh products and processed products Processed products Basic products for processing

Revenues

Price = = =

Quantity + + +Direct costs

Production =

Commercialisation +

Transaction costs

Market information

Negotiation + +

Human skills = =

Control +

Contribution + + +

Uncertainty

Price

Quantity sold

aNote: The signs indicate the direction of the changes in revenues, costs and uncertainty: +: increase; : decrease; =: similar.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456 451

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 10/14

4.2.1. Revenues

Prices in the collective marketing channels in general

are similar to those in the individual farm shops.

However, the organised channel has the advantage to

realise a hi gher turnover (more clients). The first reason

for this is that the products are more readily available to

the common consumer through the initiatives. Whilemost farm shops are located in the countryside, Farm-

ers’ Markets for example organises markets in the

village or city centres, during weekends or on evenings,

increasing accessibility. The system applied by Food-

teams also requires a smaller effort on the part of the

consumer who picks up his products every week at a

place in the neighbourhood at a time agreed upon by the

team. By doing so, Foodteams has reached many

consumers that otherwise would have continued to

buy in the common marketing channel. Fermi"eere de

M!eean and Coprosain also bring products closer to the

consumer by selecting strategically located outlets or by

participating in public markets.A second advantage of the initiatives is the wide

selection of farm products that can be bought at one

place. A third reason is that for many consumers the

collective effort is felt to contribute to the viability of the

countryside, to sustainable production and to aid

regional development. This explanation is inter alias

supported by a consumer analysis by Vannoppen et al.

(2001), Fourth, organisations such as Fruitnet, Fermi "eere

de M!eean and Coprosain spend a significant amount of

resources in marketing their products via intensive

prospecting of wholesalers, retailers, caterers, etc. Even

for relatively small initiatives such as Farmer’s Marketsmore publicity can be gained by the organisation than

by the individual farmer. With the exception of only a

few successful and strategically located farm shops,

farmers can therefore usually sell more of their products

via the initiative than they would be able to sell in their

own farm shop.

4.2.2. Direct costs

For the analysis of the direct costs, it is necessary to

make a distinction between the three groups of farmers.

For farmers selling at Farmers’ Markets or Foodteams,

production costs do not change much. Since higher

quantities are sold, some farmers mention that produc-

tion costs per unit of product decrease, for example

because of the more frequent use of fixed equipment.5 In

comparison with the farm shop, commercialisation costs

increase due to costs incurred by transport, stallage, the

license for sales activities, etc.

Farmers selling their processed farm products

through Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain also mention

a minor decrease in their production costs per unit of

product. This decrease is the result of the specialisation

(e.g. making only yoghurt instead of a whole variety of

dairy products) and the increase in production volume

made possible by the co-operatives. Commercialisationcosts, on the one hand, are slightly increased by the

need to transport products to the co-operative and

by extra packaging costs (the products are handled

more intensively than when they are sold at the farm).

But these increased costs are insignificant in com-

parison with the savings realised by the fact that farmers

do not have to spend time and money in marketing

activities, that are now being handled by the co-

operative.

The direct costs for farmers selling raw materials to

the co-operative are lower because there is no need to

invest in the processing activities taken over by the co-

operative. In particular, for these farmers new supplypossibilities (that is, the possibility to deliver to a quality

food channel) become available which otherwise would

only be possible with very high individual investments

(in material for the production of processed farm

products and in the commercialisation of these pro-

ducts).

4.2.3. Transaction costs

As indicated under Section 4.1.3, all organisations

collect information about regulations, market

conditions, consumer demands, and so forth, and

distribute this information among their members.Together with information exchanged among farmers

of the same initiative, this results in lower information

costs as compared with individual direct sale. Negotia-

tion costs in general are higher than when farmers can

set prices individually. These costs not only include

negotiation about prices, but also about quality,

quantities, applied practices. organisational aspects

(membership e.g.), etc. On the other hand, farmers can

realise an economy on negotiation costs not only

because a comparable system of negotiations with

consumers would be very expensive for the individual

farmer, but also because well-defined price systems and

quality standards reduce recurrent negotiations on these

items. With respect to the acquisition of human skills,

significant gains can be made by those farmers

selling their own products, because they are supported

in the development of these specific skills by the

central organisation (e.g. workshops organised by the

organisation).

In comparison with individual sales activities Farmers

selling at Farmers’ Markets or to Foodteams are

confronted with some extra costs incurred by the control

of their practices. They have to comply with regular

visits (by consumers or market commissioners) of their

5With regard to the investments in processing material and sales

facilities it has to be noted that all farmers interviewed started on a

small basis and expanded gradually. Bowler et al. (1995) also

concluded that ‘‘farm businesses first enter the alternative farm

enterprise pathway at the marginal level, subsequently passing to the

principal level’’ (p. 119).

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456452

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 11/14

farm and explain their practices. In Fermi"eere de M!eean

and Coprosain, these control costs are on the account of

the organisations, so that the control costs for these

farmers will be lower than with a comparable quality

and control system on an individual basis. Indirectly,

farmers do pay their part of the price tag of the controls

by accepting a lower margin and by paying theircontributions or membership fees.

When taking all factors into account, it can be

concluded that transaction costs are equal or slightly

higher for farmers who already had implied the direct

sale of fresh or processed products. For producers

delivering raw materials for the processing activity of

Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain, the new marketing

channel substantially decreases transaction costs be-

cause the co-operation, through the centralisation of

processing and marketing, realises substantial econo-

mies on information (about processing), negotiation and

control costs and in particular on the investments in

specific assets.

4.2.4. Uncertainty

An important benefit of the new marketing channels

in comparison with individual sales is that farmers are

more certain about prices and quantities sold. While an

individual farmer has to compete with other traders in

his neighbourhood, all initiatives guarantee farmers a

good price, negotiated rules (about the functioning of the

marketing channel) and the absence of price competi-

tion. The reduced uncertainty about turnover is the

result of the size of the initiatives, as already discussed inSection 4.1.4.

4.2.5. Global analysis

Our analysis reveals that in comparison with indivi-

dual direct sale, the most important benefits of

collective initiatives are a higher turnover (prices are

comparable) and a higher certainty about prices and

sales volumes. For farmers of Farmers’ Markets

and Foodteams these extra benefits offset the extra

commercialisation and transaction costs. For the farm-

ers of Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain total costs

decrease because farmers do not have to invest in the

marketing of their products (done by the co-operative).

This fully compensates for the low extra transaction

costs.

For farmers delivering basic products for processing

activities, the new marketing channel means a significant

improvement, because investment, information and

control costs are taken over by the co-operative. For

farmers who donot have excess labour time to be spent

on marketing or even processing activities, initiatives

such as Fermi"eere de M!eean and Coprosain present a

unique possibility to penetrate the market of high-

quality food products.

5. Conclusion

The theoretical model presented in Section 3 of thispaper offers a good framework to analyse farmers’

participation in innovative marketing channels.

Although the model can be characterised as a traditional

cost–benefit model, the inclusion of transaction

costs and its qualitative nature give it a broader

dimension.

The framework has been used to analyse the

participation of farmers in six innovative marketing

channels for quality food in Belgium. Overall, the

balance is positive: the higher margins and in particular

the savings on private transaction costs (mainly invest-

ments in specific knowledge and assets) offset the higher

costs for the farmers.Our analysis proves that co-operation between farm-

ers can overcome the problems that inhibit farmers from

developing a direct selling activity. These problems,

mentioned by inter alias Battershill and Gilg (1998b)

and Festing (1997), include among others: inappropriate

farm location with consequently low turnover; the need

for investments; the lack of marketing talent; the

complexity of health and hygiene regulations. Co-

operation even allows farmers who are not able to

invest resources and labour into processing or

marketing activities to enter the market of quality

production.A second conclusion is that these organisations

are able to promote innovations which would

probably not take place under pure market governance.

Bundling resources and capacities has been shown to

reduce the risk of failure of individual farmers

(Sgaard, 1994; Morgan and Murdoch, 2000). Many

of the farmers in the initiatives we interviewed have

invested in more sustainable production methods only

because the initiative ensured them an outlet for their

products.

Collective marketing channels have the capacity to

organise a quality insurance system which individual

farmers cannot develop because of the very high costs

involved. Only co-operation can sufficiently cut the costs

and make the necessary investments in specific skills and

assets (Raynaud and Sauv!eee, 2000).

For the rural sector as a whole, it is important to

reflect on such new production and marketing models at

a time of growing consumer concerns regarding food

quality and public concerns regarding health and

environmental issues. Initiatives based on direct market-

ing or labelled products (like the ones studied in this

paper) can be regarded as pioneers to find such new

constructions. It would even be possible to involve the

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456 453

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 12/14

transformation and distribution sector as illustrated by

the integrated fruit production initiative Fruitnet.

However, as our analysis indicates, the changes in the

transaction costs can be substantial, even at the farm

level. It is imperative to include these costs in any cost–

benefit analysis of such innovative processes. A common

failure of many initiatives is that transaction costs arenot adequately budgeted: because they are not directly

tangible, these costs are not accounted for by volunteers,

in particular at the start of an initiative. When initiatives

grow, and these costs become visible, organisations have

to be prepared for these expenses; if not, and if they do

not adapt their governance structure, this can lead to

difficulties or even failure of initiatives. A good historic

example would be the many Farmers’ Markets, which

started up in the 1980s but disappeared after the

pioneers started to withdraw from participation. We

therefore believe that further research should identify

and measure transaction costs. When transaction costs

are better quantified, farmers and emerging initiativescan become more aware of their existence and can take

them into account from the start.

Appendix A. Mathematical derivations from the basic

model

A.1. Profitability of a marketing channel

Pchain ¼ Pp þPm þPs

with

Pp ¼ PpQp rpI p TCp;

Pm ¼ PmQm PpQp rmI m TCm;

Ps ¼ PsQs PmQm rsI s TCs;

Pchain ¼ PpQp rpI p TCp þ PmQm PpQp rmI m

TCm þ PsQs PmQm rsI s TCs;

Pchain ¼ PpQp PpQp þ PmQm PmQm þ PsQs rpI p

rmI m rsI s TCp TCm TCs;

Pchain ¼Pp þPm þPs ¼ PsQs rpI p rmI m rsI s

TCp TCm TCs:

A.2. Relati ve profitability of a labelled marketing channel

P1 ¼ Ps1Qs1 rp1I p1 rm1I m1 rs1I s1 TCp1

TCm1 TCs1;

P2 ¼ Ps2Qs2 rp2I p2 rm2I m2 rs2I s2 TCp2

TCm2 TCs2;

DP ¼ P1 P2

¼ Ps1Qs1 rp1I p1 rm1I m1 rs1I s1

TCp1 TCm1 TCs1 Ps2Qs2 þ rp2I p2

þ rm2I m2 þ rs2I s2 þ TCp2 þ TCm2 þ TCs2

¼ ðPs1Qs1 Ps2Qs2Þ ðrp1I p1 rp2I p2Þ

ðrm1I m1 rm2I m2Þ ðrs1I s1 rs2I s2Þ

ðTCp1 TCp2Þ ðTCm1 TCm2Þ

ðTCs1 TCs2Þ

with: rm1I m1 ¼ rm2I m2 and rs1I s1 ¼ rs2I s2

DP ¼ DPsQs DrpI p DTCp DTCm DTCs:

A.3. Relati ve profitability of a direct sale marketing

channel

P1 ¼ Ps1Qs1 rp1I p1 TCp1;

P2 ¼ Ps2Qs2 rp2I p2 rm2I m2 rs2I s2 TCp2

TCm2 TCs2 ¼ Ps2Qs2 Sr2I 2 STC2

DP ¼ P1 P2

¼ Ps1Qs1 rp1I p1 TCp1 Ps2Qs2 þ Sr2I 2 þ STC2

with: Ps1Qs1 ¼ Ps2Qs2

DP ¼ ðSr2I 2 rp1I p1Þ þ ðSTC2 TCp1Þ:

Appendix B. Description of the six case studies

Fruitnet commercialises integrated pip-fruit under theFruitnet label. About 117 farmers were members of

Fruitnet in 1997. Fruitnet co-ordinates product sales by

negotiating a price with the main buyer of the products

and by assigning and distributing the orders to the

different producers. The chain consists of all the

traditional actors (producer, auctioneer, distributor

and consumer). Fruitnet co-ordinates the transactions

and the inspections of the products.

Produits de Qualit!ee d ’Autrefois (ProQA) is a small

beef co-operative of seven farmers and a cattle

merchant. They produce and sell beef under the officially

recognised BBF (‘‘Blanc Bleu Fermier’’) label which is a

public quality label of the Walloon government. This

labelled beef if sold to about 20 local butchers who

exclusively sell ProQA beef. The chain consists of all the

traditional actors.

The marketing channel Coprosain entails a co-

operative of farmers called Agrisain. The latter sells its

products to Coprosain, a co-operative, that resells these

products to the consumers, sometimes after some

processing. Coprosain has expanded its scope from

farm products (mainly milk products and fresh vege-

tables and fruits) and farm chickens to beef and other

meats, and is currently adding the processing of pork to

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456454

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 13/14

its activities. The farmers producing beef and pork

follow a code of practiceFtheir products are sold under

a label (‘‘BBF’’ for beef; ‘‘Porc Fermier’’ for pork).

While Coprosain has been founded by the producers, it

has now developed into a family firm. The marketing

chain Coprosain now consists of the producer, the co-

operative and the consumers. With the expansion anddiversification of their activities, the chain has continued

to grow because retailers and even wholesalers have

become involved.

In fermi "eere de M !eean, a co-operative, producers and

consumers co-operate to promote and commercialise

farm products. The co-operative also produces a variety

of cheeses according to traditional methods. Since both

producers and consumers are represented in the co-

operative, there is a more or less direct link between

them. However, over the last few years the co-operative

has expanded her business, and the link with the

producers has been diminishing because the products

are now no longer being sold directly and exclusively toconsumers but also to retailers and wholesalers.

Farmers’ markets are held weekly, public markets on

which farmers sell their farm products directly to the

consumer. Both the farmers and some consumers are

represented in a market council that manages the

market. Consumers are gathered in a market committee

that controls the products (authenticity of the products,

quality, prices, etc.) and negotiates with the farmers to

obtain uniform prices.

Foodteams is a consumer initiative consisting of small

teams of 10–15 families who agree to buy farm products

from local farmers. The families always engage them-selves for a full year. The two organisations that

engaged in this initiative take care of the search for

consumers and producers, the setting up of new teams

and the administration of the whole initiative. However,

once the teams have started up their activities, there is a

strong emphasis on auto-organisation in order to reduce

the need for help from the co-ordinating organisations.

References

Arfini, F., Mora, C., 1998. Typical products and local development:

the case of Parma area. In: Arfini, F., Mora, C. (Eds.), Typical andTraditional Products: Rural Effect and Agro-industrial Problems.

Universit"aa di Parma, Parma, pp. 169–186.

Barberis, C., 1999. Les micromarch!ees de produits typiques, une chance

pour la soci!eet!ee rurale. Comptes Rendus de l’Academie

d’Agriculture de France 85, 275–280.

Bates, S., Fearne, A., Wilson, N., 1996. Factors affecting the

marketing of UK potatoes: results of a survey of UK potato

growers. Farm Management 9 (5), 240–250.

Battershill, M.R.J., Gilg, A.W., 1998a. Quality farm food in Europe: a

possible alternative to the industrialised food market and to current

agri-environmental policies: lessons from France. Food Policy 23

(1), 25–40.

Battershill, M.R.J., Gilg, A.W., 1998b. Traditional low intensity

farming: evidence of the role of vente directe in supporting such

farms in Northwest France, and some implications for conserva-

tion policy. Journal of Rural Studies 14 (4), 475–486.

Bessiere, J., 1998. Local development and heritage: traditional food

and cuisine as tourists attractions in rural areas. Sociology Ruralis

38 (1), 21–34.

Bowbrick, P., 1992. The Economics of Quality. Routledge, London.

Bowler, I., Clark, G., Ilbery, B., 1995. Sustaining farm businesses in

the less favoured areas of the European Union. In: Sotte, F. (Ed.),The Regional Dimension in Agricultural Economics and Policies.

Universit"aa di Ancona, Ancona, pp. 109–120.

Brasili, C., Fanfani, R., Montresor, E., Pecci, F., 1998. The local

systems of the food industry in Italy. In: Arfini, F., Mora, C.

(Eds.), Typical and Traditional Products: Rural Effect and Agro-

Industrial Problems. Universit"aa di Parma, Parma, pp. 419–440.

Chubb, A., 1998. Farmers’ Markets: The UK Potential. Ecological

books, Bristol.

de Sainte-Marie, C., Prost, J.-A., Casabianca, F., Casalta, E., 1995. La

construction sociale de la qualit!ee- enjeux autaur de l’Appellation

d’Origine Control!eee ‘‘Brocciu corse’’. In: Nicolas, F., Valceschini,

E. (Eds.), Agro-alimentaire: une !eeconomie de la qualit!ee. INRA-

Economica, Paris, pp. 185–197.

de Sainte-Marie, C., Valceshini, E., 1996. Les r!eepr!eesentations de la

qualit!ee "aa travers les dispositifs juridiques. In: Casabianca, F.,

Valceschini, E. (Eds.), La qualit!ee dans l’agro-alimentaire:

!eemergence d’un champ de recherches. INRA-SAD, Paris, pp. 26–

33.

Falconer, K., 2000. Farm level constraints on agri-environmental

scheme participation: a transactional perspective. Journal of Rural

Studies 16 (3), 379–394.

Fanfani, R., Green, R.H., Pecci, F., Rodribuez-Zuniga, M., 1996. I

sestemi di produzione della carne in Europa: un analisi comparata

tra filiere e sistemi locali in Francia, Italia e Spagna. Milano,

Franco Angeli sr1.

Feenstra, G., 1997. Local food systems and sustainable communities.

American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 12 (1), 28–36.

Feensta, G., Lewis, C., 1999. Farmers’ markets offer new business

opportunities for farmers. California Agriculture 53 (6), 25–29.

Festing, H., 1997. The potential for direct marketing by small farms in

the UK. Farm Management 9 (8), 409–421.

Festing, H., 1998. Farmers’ Markets: An American Success Story.

Ecological Books, Bristol.

Fonte, M., 1999. Sistemi alimentari, modelli di consumo e percezione

del rischio nella soieta tardo moderna. Questione Agraria 76,

13–36.

Grey, M.A., 2000. The industrial food stream and its alternatives in the

United States: an introduction. Human Organisation 59 (2), 143–

150.

Hinrichs, C.C., 2000. Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on

two types of direct marketing. Rural Studies 16 (3), 295–303.

Hobbs, J.E., 1995. Evolving marketing channels for beef and lamb in

the United KingdomF

a transaction cost approach. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 7 (4), 15–39.

Hobbs, J.E., Young, L.M., 1999. Increasing vertical linkages in

agrifood supply chains: a conceptual model and some preliminary

evidence. Paper presented at the meeting of the Canadian

Agricultural Economics Society and the Western Agricultural

Economics Society, Fargo (North Dakota). Research Discussion

Papers, University of Saskatchewan, Canada, no, 35.

Holleran, E., Bredahl, M.E., Zaibet, L., 1999. Private incentives for

adopting food safety and quality assurance. Food Policy 24 (6),

669–683.

Holloway, L., Kneafsey, M., 2000. Reading the space of the farmers’

market: a preliminary investigation from the UK. Sociologia

Ruralis 40 (3), 285–299.

I. Verhaegen, G. Van Huylenbroeck / Journal of Rural Studies 17 (2001) 443–456 455

8/13/2019 Verhaegen Ande Huylenbroeck

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/verhaegen-ande-huylenbroeck 14/14

Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M., 1998. Product and place: promoting quality

products and services in the lagging rural regions in the European

Union. European Urban and Regional Studies 5 (4), 329–341.

Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M., 2000. Protecting and promoting regional

specificity food production: a case from south west England.

Journal of Rural Studies 16 (2), 217–230.

Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M., Bamford, M., 2000. Protecting and

promoting regional speciality food and drink products in the

European Union. Outlook on Agriculture 29 (1), 31–37.

Lassaut, B., Sylvander, B., 1998. Producer-consumer relationships in

typical products supply chains: where are the theoretical differences

with standard products? In: Arfini, F., Mora, C. (Eds.), Typical

and Traditional Products: Rural Effect and Agro-industrial

Problems. Universit"aa di Parma, Parma, pp. 169–186.

Marsden, T., Arce, A., 1995. Constructing quality: emerging food

networks in the rural transition. Environment and Planning A 27,

1261–1279.

Morgan, K., Murdoch, J., 2000. Organic versus conventional

agriculture. Knowledge, power and innovation in the food chain.

Geoforum 31 (2), 261–270.

Morris, C., Young, C., 2000. ‘Seed to shelf’, ‘teat to table’, ‘barley to

beer’ and ‘womb to tomb’: discourses of food quality and quality

assurance schemes in the UK. Journal of Rural Studies 16 (1),

103–115.

Mormont, M., Van Huylenbroeck, G., 2001. A la recherche de la

qualit!ee. Analyses socio-!eeconomiques sur les nouvelles fili!eeres agro-

alimentaires. Synopsis, Les Editions de l’Universit!ee de Li!eege, Lie ´ ge.

Murdoch, J., Marsden, T., Banks, J., 2000. Quality, nature and

embeddedness: some theoretical considerations in the context of

the food sector. Economic Geography 76 (2), 107–125.

Nygard, B., Storstad, O., 1998. De-globalisation of food markets?

Consumer perceptions of safe food. The case of Norway. Socio-

logis Ruralis 38 (1), 35–53.

Raynaud, E., Sauv!eee, L., 2000. Common labelling and producer