value of philosophy, the second the nature of truth, and...

Transcript of value of philosophy, the second the nature of truth, and...

Introductory Matters

The readings in this section take up some topics that set the stage for discussion to follow. The first addresses the value of philosophy, the second the nature of truth, and the third the nature of good reasoning. Russell’s piece on the value of philosophy should help give us a picture of what we can hope for out of the philosophical discussions to follow. My short paper on truth should illuminate what is at issue in debates about various claims. And the discussion of reasoning should help us go about our philosophical arguing in constructive ways.

But this material is not a mere prelude to serious philosophical discussion. As the readings on truth and good reasoning suggest, the nature of truth and of good reasoning are themselves topics of serious philosophical debate. Our goal will not be to decide the debates about truth and reasoning. But we will want to understand enough about the issues surrounding truth and reasoning to see something of the qualifications and lack thereof which must be placed on further discussion.

1

The Problem of Evil

Though evil is certainly a problem, the philosophical “problem of evil” is a problem for theistic religious belief that is, for belief in an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good god. In its simplest form, the problem may be represented as follows:

1. If there is an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good god, then there is no evil.

2. There is evil. 3. There is no omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good god.

The argument is deductively valid. And, in typical cases, theists accept that there is evil indeed, the point of many religious beliefs and practices has to do with responses to evil. So most controversy surrounds premise (1).

The readings in this section divide into two groups. First, Gyekye introduces, from a non-Western perspective, many topics that will arise in later discussion. The problem is more than a narrowly Western issue! Rowe’s piece is another general and accessible introduction. The latter two readings, by Mackie and Plantinga, interact directly with one another. Mackie argues that the problem is real: the argument is sufficient to show that there is no omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good god. Plantinga responds directly to Mackie’s reasoning, advocating a version of the “Free Will” defense. You will want to think about which is right or, maybe, whether neither succeeds in establishing his point!

43

The Kal m Cosmological Argument.

The cosmological argument (from the greek “ ù ” for “world” or “universe”) comes in different forms. In each case, the idea is to move from the existence of the world to the conclusion that there is a creator. The kal m version of the argument, is based on the impossibility of an infinite past, and was advocated especially by Arabic philosophers in the late Middle Ages. In recent years, it has been defended vigorously by William Lane Craig. As presented by Craig, the basic argument is as follows:

1. Everything that begins to exist has a cause of its existence.

2. The universe began to exist. 3. The universe has a cause of its existence.

The argument is deductively valid. Our discussion focuses almost exclusively on the second premise and on just one of Craig’s main arguments for it. With just this much, there will be complications enough! And we should be able to get a good taste of the kind of reasonings that are involved.

The readings trace a sort of “trail” or “sequence”: The first selection, by Craig, sets up the basic terms of the argument. In the second selection, we get a medieval defense of the second premise based on the absurdity of an infinite past. A simplified version of this argument is as follows.

1. Nothing is greater than infinitely big.

2. A whole is greater than its proper parts.

3. The totality of time elapsed up to now is a proper part of that which will have been elapsed after now.

4. The totality of time elapsed up to now is not infinite.

With second and third premises, assuming that the totality time elapsed up to now is infinite leads to the conclusion that it will be greater than infinite in a moment – which contradicts the first premise. But many have thought this reasoning is discredited by the treatment of infinity in contemporary mathematics, on which both the first and second premises are called into question. Thus the third selection, by Maor, introduces the contemporary approach to infinity. The final two selections develop Craig’s attempt to sustain the argument in the face of these objections.

83

Divine Command Ethics

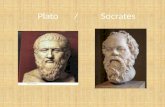

On a divine command ethical theory, an action is wrong if and only if it violates a command of god. Indeed, it is sometimes suggested that moral notions are somehow senseless without god that “without god, all things are permitted.” Say we grant that god introduces certain motivation and/or enforcement for moral values. Still, there is room to question the divine command theory. In one of the great moments in Plato’s dialogues, in Euthyphro, Socrates sets up a dilemma which may be represented as follows:

DCT: An act is wrong iff it violates a command of god.

There is an external criterion forwongness

Wrong is arbitrary; any act couldbe wrong

Socrates asks us to consider whether god commands a thing because it is wrong, or whether it is wrong because god commands it. Suppose god commands a thing because it is wrong (the right-hand option): Then god seems cast into a merely advisory or enforcement role – it is not god, but some other factor, determining the wrong. Suppose a thing is wrong just because of god’s command (the left-hand option): Then it seems that any acts could be right or wrong depending on god’s commands: If it is possible for god to command the torture of innocent children, it is possible for it to be morally right to torture them. But if moral facts are not changeable in this way, if it cannot be right to torture, then this left option does not seem correct either. And if neither option is correct, we have a serious objection to the DCT. (Observe that the last objection does not say that god has commanded the unthinkable or that he would, only that he could.)

Our readings form a sort of dialogue on this question. The initial readings, by Plato and Hudson, set up the divine command theory, and develop traditional objections to it. In the next selection, Robert Adams proposes a “modified” divine command theory intended to avoid the objections. In the fourth selection, John Chandler argues that the traditional objections continue to apply to Adams’s modified theory in modified form. Finally, I suggest that these debates focus more on a symptom, than the cause of difficulty and, in the last selection, propose a theory which I think goes more directly at the cause. Of course, my theory may have problems of its own!

112

158

Pascal’s Wager Pascal proposes that the way to decide whether or not to believe in god is to discover whether belief or disbelief is the better bet, and bet accordingly. You win if the view you bet on is true. Pascal writes within a particular Christian tradition, and some aspects of his presentation are tied to that tradition. However, it is possible to consider his argument without that emphasis. Setting aside the possibility of infinite loss, let an r-view be any view offering infinite gain that has probability > 0; let an a-view be any view not offering infinite gain that has probability > 0; and let a d-view be any view whose probability is 0. We argue that a bet on an r-view more rational than a bet on an a- or d-view. 1. One must bet either for some r-view, a-view or d-view. 2. The expected utility of bets on arbitrary r-views, a-views, and d-views are, EU(r) = prob(r)(infinite gain) + prob(not-r)(finite loss) = infinite gain EU(a) = prob(a)(finite gain) + prob(not-a)(finite loss) = finite gain/loss EU(d) = 0(some gain) + 1(finite loss) = finite loss 3. If one must bet, it is rational to take a bet with highest expected utility. ––––––––––– 4. It is rational to bet on some r-view, rather than on any a-view or d-view.

So the conclusion of this version of the argument is that it is rational to be religious rather than not (or rather to bet on an r-view — where this is any view with a chance of being true and a promise of infinite gain). Note that we do not defend any particular religion. The second premise is based on ordinary betting considerations: The expected utility of a bet is equal to the probability of a win times the payoff of a win, plus the probability of a loss times the payoff of a loss. Thus, e.g., for a $.50 bet on a single roll of a die, suppose I am offered a $5 payoff for a bet on six. Then I may reason as follows: My net gain for a win is 4.50, and loss is .50. My expected utility is the probability of a win times the gain of a win, plus the probability of a loss times gain of a loss, where this is, (1/6)(4.50) + (5/6)(-.50) = 1/3. So I expect an average gain of .33/roll – and take this bet as often as I can! Here’s another way to see the point: In any six rolls, I expect to win once (and so to gain 4.50), and to lose 5 times (and so to lose 2.50), so I expect to come out ahead by $2.00 – the same as at 1/3 per roll over 6 rolls. Given this, the basic idea of the Wager is clear: So long as the probability of a win is non-zero, the expected utility of a bet on god is sure to be huge. It’s related reasoning – on the loss side – which motivates people to buy insurance. Of course, this isn’t the end of the matter. But it should help you to see what is at issue!