Usa Stratified Monopoly

-

Upload

cumulo-obseso -

Category

Documents

-

view

39 -

download

0

Transcript of Usa Stratified Monopoly

-

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY: A SIMULATION GAME ABOUT SOCIAL CLASS STRATIFICATION*

EDITH M. FISHER

Western Michigan University

Teaching Sociology, Vol. 36, 2008 (July:272-282) 272

EFFECTIVELY TEACHING COLLEGE STU-DENTS about social class stratification is a difficult challenge. Explanations for this difficulty tend to focus on the students who often react with resistance, paralysis, or rage (Davis 1992). They have relatively little work experience outside the service industry (Corrado et al. 2000) and limited awareness of social class stratification ex-cept for numerous stereotypes (Jessup 2001; Miller 1992; Tiemann, Davis, and Terri 2006).

Students tend to overestimate individual causes and effort, and underestimate situ-ational determinants when accounting for social inequality (Ross 1977). They have been taught to value individualism and com-petition and to believe in the American Dream, which is based on cultural beliefs and values that support the economic status quo (Tiemann et al. 2006:398). Because students have been taught to believe equality and fairness govern the economic system in the United States, they adhere to bootstrap ideology, which suggests that inequality exists because people possess different lev-els of drive and ability (Brezina 1996).

Sociologists have been using games and simulations as alternative methods for sev-eral decades to teach about these sensitive

subjects (Coleman et al. 1973; Greenblat 1971; Greenblat and Duke 1981; McKeachie 1999). Games are contests gov-erned by rules that synthesize cognitive and affective learning, while simulations are games that represent selected fragments of reality (Jessup 2001). Teachers of sociology use simulation games as an effective means of bridging sociological abstractness and direct experience (Davis, Duke, and Gam-son 1981; Goldsmid and Wilson 1980). Another advantage is that they are effective referents for ongoing learning, because stu-dents retain information longer and prefer them to traditional methods. Some research indicates that games are at least as effective, and in some cases more effective, than tra-ditional methods (Coleman et al. 1973; Jes-sup 2001; Petranek 1994; Randel et al. 1992).

There are many examples of games to teach about social class stratification in the literature. After randomly assigning groups of students a race, class, and gender, Wetcher-Hendricks and Luquet (2003) gave groups different sized boxes of crayons and asked them to draw objects without sharing crayons. Similarly, Corrado et al. (2000) asked groups to create the same objects with different allocations of playdoh to demon-strate the effects of unequal distribution of resources. Ghetto is a game designed to sensitize privileged students to the living conditions of the poor (Miller 1992).

Several simulation games focus on the issues surrounding social class stratification and social change. Starpower is a simulation game where players exchange resources of unequal value in a system where the rules favor the wealthy and the most privileged group is eventually given the power to make the rules governing the game. Sociopoly utilizes teams playing the board game Mo-

*The author would like to thank the anony-

mous reviewers as well as Dana Atwood-Harvey, David Hartmann, Patricia Sanders, Thomas Van Valey, Robert Wait, and Carol White for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Please address all correspondence to the author at Center for Gender and Womens Studies, Western Michigan University, Kalama-z o o , M I 4 9 0 0 8 ; e - m a i l : [email protected].

Editors note: The reviewers were, in alpha-betical order, Karen Albright and Michael Jes-sup.

-

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY 273

nopoly with modified rules to illustrate the resource distribution discrepancies of the social stratification system. The rules and resource distribution favor the white team while discriminating against the Hispanic, African-American, and single mother teams (Jessup 2001).

Some simulation games focus on social change and individual action. Glasberg et al. (1998) use a variety of board games to allow students to see images and messages of race, class, gender, and political sociali-zation that are embedded within; and to explore how they may challenge and sub-vert those messages. In the game Anti-Monopoly students compete to return the economy to a competitive free enterprise system.

One disadvantage of simulation games is the time required to play them, which can range from one to multiple class sessions. Another is the complexity of the activity for the students and the additional work for teachers (Petranek 1994). After summariz-ing over 150 studies, Coleman et al. (1973) conclude that some difficulty exists in help-ing students with lower abilities to grasp the connections between the games and real life abstractions. More recent studies have up-held this conclusion (Randel et al. 1992).

More importantly, although simulation games may increase awareness of structural limitations, they do not dismiss individual-ism. Because individualistic logic is so accommodating, individual successes in the face of structural barriers may appear all the more impressive (Brezina 1996:219). Fur-thermore, these exercises may leave stu-dents with the mistaken impression that so-ciological views of inequality leave no room for the importance of individualistic factors such as personal drive and ability (1996:218).

USA Stratified Monopoly was designed to demonstrate social class stratification, inte-grating issues of individualism and social change. The game can be played in one class period and is relatively simple to play. Abstractions are easier to make because the

students are dealing specifically with capi-talism within the game. Unlike Sociopoly (Jessup 2001), players are divided solely by social class stratification, individuals play the games rather than teams, and the differ-entiations between the classes in USA Strati-fied Monopoly have much more depth.

In addition, while the game can be played at any time within the semester, it works best immediately following their reading of the assigned materials on social class strati-fication. When they come prepared to dis-cuss the materials they just read, students tend to be relieved and excited to discover that we will be playing a game instead. The remaining sections of this article are de-voted to a discussion of the game and its objectives, the pre-game instructions, the post-game process, and its assessment.

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY

OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives USA Stratified Monopoly gives students an opportunity to: understand social inequality as a

position in the socioeconomic class system [that] is characterized by differ-ential POWER (the ability to achieve ones will), PRESTIGE (the respect af-forded ones social status and occupa-tion), and PRIVILEGE (the rewards that one enjoys by virtue of his/her power and prestige) (Miller 1992:317);

experience the structural limitations in-herent in the U.S. social class system;

generalize those structural limitations to other social institutions and categories of stratification;

understand individualism within the limi-tations of the structure;

develop empathy by taking on the roles of people of different social classes;

critically analyze the participants values and stereotypes;

encounter social change; and critically analyze their beliefs about the

American Dream.

-

274 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY

Game Objective After random assignment into a social class (upper-class ruling elite, middle-class, working class, and lower class), each player is given access to resources in accordance with their stratified social locations. Ac-cordingly, each player experiences a unique set of rules by which to play the game. Al-though the rules are now different for each player according to their social class, the sole object of the game remains the same: to win by bankrupting all the other players with your overwhelming wealth. USA Stratified Monopoly, as with Monopoly, rewards cutthroat competition and Machia-vellian behavior that underscores social Darwinism. One wins by playing fero-ciously, regardless of how ones friends or fellow players might feel (Glasberg et al. 1998:133).

THE PRE-GAME INSTRUCTIONS

The pre-game instructions are extremely important because they set the stage for the game and the energy in the room. The role of the teacher is crucial; the effectiveness of this game depends on the delivery of the pre-game instructions and the active moni-toring of the game itself. A minimalist ap-proach to the pre-game instructions is to give students copies of the rules and let them play or simply to read the instructions to students. Research shows that interactive teaching is more effective than traditionalist teaching with extroverted students and equally effective with introverted students (Goldsmid and Wilson 1980; McKeachie 1999). Therefore, generating dialogue with students about the rules is the preferred approach.

Attend to each rule individually, as shown in Table 1, asking students how each rule approximates the real world. Offer exam-ples of people from opposite social classes, and ask students if these people have equal access to resources, power, prestige, and privilege associated with this rule. Once students establish that inequality exists in the real world, go over the discrepancies

within that rule of USA Stratified Monopoly. By using humor and energy, students are emotionally and psychologically better pre-pared to play. By addressing each rule indi-vidually and connecting it to real world ex-amples, students are better prepared to gen-eralize to the real world from the events of the game.

It is important to never tell students in advance that they will be playing with Mo-nopoly boards. Experience has taught me that some students have an intense aversion to the game itself and will skip class just to avoid having to play. As students enter the room at the beginning of the class period, instruct them to quickly get into groups of four and to place an empty desk between them to serve as a table. Some students pre-fer to sit on the floor, which also works well. If the number of students in atten-dance is not perfectly divisible by four, have any remaining students stand on the side lines until further notice.

Pass out one game to each group and in-struct them to take out only the dice. Stu-dents take turns rolling the dice until they have established an order within their group from the highest to the lowest numbers rolled. Afterwards, tell them that because social class is an ascribed status (unearned) at birth and that we have no choice into which family we are born, the numbers they rolled decided their lots in life. The student who rolled the highest number plays the upper-class ruling elite, and the student who rolled the lowest number plays the lower class. The students who rolled the second and third highest numbers play the middle and working classes, respectively. Explain that the four-class model of social stratifica-tion is but one of many stratification theo-ries. Because it best suits the board game and is one that is familiar to most students, it is the model chosen for this simulation game.

Remind students that the population of the United States is not evenly distributed be-tween these four groups. Draw a triangle on the board to illustrate how the upper-class ruling elite represent the tiniest tip (1%),

-

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY 275

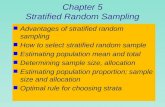

Table 1. Rules for USA Stratified Monopoly by Social Class

RULE

Rolling Dice for Social Class

Highest number Second highest number

Third highest number

Lowest number

Controlling Bank Allowed Not allowed Not allowed Not allowed

Controlling Rules Allowed Not allowed Not allowed Not allowed

Living Conditions

Boardwalk blue and green

Indiana red and yellow

New York orange and violet

Baltic purple and pale blue

Selecting Token First Second Third Last

Taking Turn First Second Third Last

Buying Residential Property

All neighborhoods

Own and two less-er neighborhoods

Own and one less- er neighborhood

Only own neighborhood

Buying Public Utilities

Allowed

Not allowed

Not allowed

Not allowed

Buying Public Transportation

Allowed

Not allowed

Not allowed

Not allowed

Buying Houses/Hotels

Regular rules

Regular rules

Regular rules

Regular rules

Paying Income Tax

None $150 $100 $25

Paying Luxury Tax

Regular rules Regular rules Regular rules Regular rules

Rolling Doubles Privileges

Get another turn

Get another turn

Get another turn

Get another turn

Rolling Doubles Penalties

None

Go to jail on fourth roll

Go to jail on third roll

Go to jail on second roll

Parking Free Free access $50 tax $25 tax Go directly to jail

Visiting Jail Earns $250 Free Free Free

Collecting Rent At all times Not in jail Not in jail Not in jail

Going to Jail

Go directly to Go and get another

turn

Go directly to jail and do not pass Go

Go directly to jail and do not pass Go

Go directly to jail and do not pass

Go

Getting Out of Jail

On next turn pay $50 or roll number

that is even or greater than six

On next turn pay $50 or roll even

number

On next turn pay $50 or roll doubles

On next turn pay $50 or roll doubles

Starting Assets $2,500 $1,500 $1,000 $500

Passing Go $250 $150 $100 $50

Getting Chance and Community Chest Cards

Regular rules with new salary for

passing Go

Regular rules with new salary for

passing Go

Regular rules with new salary for

passing Go

Regular rules with new salary for

passing Go

SOCIAL CLASS

UPPER MIDDLE WORKING LOWER

-

276 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY

while the lower class represent the large base of the triangle. Tell them of the gen-dered nature of social class stratification and direct attention to any remaining students waiting on the side lines. In keeping with the gendered nature of social-class stratifi-cation, instruct the male students to choose a group and sit with the working-class player and the female students to choose a group and sit with the lower-class player.

Students open their game boards and place the sides with the coveted Boardwalk and Park Place properties directly in front of the players representing the upper-class ruling elite. All the other players need to get up and relocate to the sides of the boards that represent their ap-propriate neighborhoods. The middle-class player sits to the right of the upper-class ruling-elite player. The working-class player sits directly across from the upper-class ruling-elite player. The lower-class player sits to the left of the upper-class rul-ing-elite player.

When the game begins, the upper-class ruling-elite players have the privilege of the first choice of tokens and the first roll of the dice. Other players may choose their tokens and take their turns counter-clockwise in descending order of social class. The upper-class ruling-elite players control the bank and all the assets, because the major differ-ence between the upper-class ruling-elite and the other social classes is ownership. Remind them that Karl Marx discussed class stratification in terms of only two so-cial classesthe bourgeoisie (the Haves) and the proletariat (the Have Nots). After briefly clarifying the difference between working at a factory, managing a division of the factory, being the CEO of the fac-tory, and owning the factory, tell them the stratified restrictions for buying residential property, public transportation (railroads) and utilities (see Table 1). While all the players may roll the dice and move freely throughout each neighborhood, they are restricted to purchasing residential proper-ties either within their own neighborhood or those of lesser value.

To be consistent with the American Dream, the opportunity to better their lives by buying houses and hotels is the same for all players regardless of social class. Tell students the stratified rules for landing on the income tax space located in the lower-class neighborhood of the playing board and remind them that in the United States, eve-rybody has to pay equal luxury taxes when they squander their money on luxuries.

Ask students if the law is blind to social class or if the behaviors associated with some classes are deemed illegal more often than those of others. After one or two re-sponses are shared, explain the privileges and stratified penalties for rolling doubles. In addition, the space marked Free Park-ing located in the corner of the board be-tween the middle- and working-class neighborhoods is free only to the upper-class ruling-elite players. The middle- and working-class players must pay the bank a stratified maintenance fee based on a per-centage of their income, while the lower-class players must go directly to jail on charges of vagrancy and trespassing. While visiting jail is free to all players, when up-per-class ruling-elite players visit the jail, the bank pays them $250. Similarly, while players are incarcerated, only the upper-class ruling-elite players are allowed to col-lect rent. Then, disclose the stratified rules for going to and getting out of jail (see Ta-ble 1).

Remind students that all citizens of the United States do not start out at birth with equal assets. For example, when the Presi-dents children were born, those babies did not have the same amount of money in their trust funds as did the babies born to a single mother living in a New York City ghetto. Accordingly, the banker distributes the stratified starting funds to each player as specified in the rules (see Table 1).

Finally, instruct the banker the stratified income to distribute to players for Passing Go, according to the rules (see Table 1). Once again, to remain true to the spirit of the American Dream, the rules for landing on Chance and Community Chest

-

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY 277

cards are the same for all players, regard-less of social class. The only difference is the stratified income for Passing Go must be followed instead of the traditional $200 as indicated on the cards. At this point, in-struct the upper-class ruling-elite players to select their tokens and start playing the game.

THE GAME

While the rules of USA Stratified Monopoly are effective at sensitizing students to the structural limitations and inequalities within our social class stratification system, they are less effective at pointing out individual-ism or social change. The process of the game, as shown in Table 2, more directly addresses these issues. After an initial pe-riod of play, interrupt the game to ask which social class controls the law in the real world. Declare that the upper-class ruling-elite players now have the power to make or change any rule at any time for the rest of the game.

After a second period of play, interrupt the game to remind students what happened to the social-class stratification system dur-ing the French Revolution. After reassuring them that no one will be decapitated, de-clare a revolution; the power hierarchy has just been flipped. Instruct the students play-ing the upper-class ruling elite and the lower class at each group to stand up and

switch seats. Remind the newly appointed upper-class ruling-elite players that they maintain the power to alter the rules as they please for the remainder of the game. After this third period of play, declare that the world has just ended and so has the game USA Stratified Monopoly.

THE POST-GAME PROCESS

While the game provides the experiences and emotions, it is the debriefing process afterwards where the most learning occurs. Once again, the role of the teacher is cru-cial. The importance of effective facilitation of this step to the successful completion of the learning objectives of simulation games cannot be stressed enough. Thatcher argues that teachers neglect the debriefing at their peril (1990:272). I approach debriefing as a three-step post-game process: clean up, discussion, and writing assignment.

Clean Up Immediately after announcing the end of the world, ask students which social class does the dirty work in the real world. Inevitably some students suggest that it is the poor. Remind them that the lower class are fight-ing to stay alive and wish they had opportu-nities to do the dirty work, while members of the working class are trying to get by and begrudgingly serve us our french fries, re-move our trash, and scrub our toilets. Then,

Table 2. Game Process for USA Stratified Monopoly by Class Session Length

GAME PROCESS

50 minutes 75 minutes 100 minutes

Pre-Game Instructions 15 minutes 20 minutes 25 minutes

Initial Game Time 10 minutes 15 minutes 15 minutes

Upper Class Makes Rules 5 minutes 10 minutes 15 minutes

Post-Revolution Power 5 minutes 10 minutes 15 minutes

Post-Game Discussion 5 minutes 5 minutes 5 minutes

Post-Game Clean Up and Writing Assignment

5 minutes

5 minutes

5 minutes

CLASS SESSION LENGTH

-

in accordance with this reality, declare it the responsibility of the working-class players to return the game boards in their original conditions. Discussion For the discussion and writing assignment, I use the Petranek model (1994). After a simulation game, teachers must help stu-dents understand the events of the game; express their emotions; generate empathy by experiencing different roles; generate and analyze explanations of the events and their emotions; determine if the events within the game and their emotions simulated everyday reality; and generalize (employ) the events of the game and their emotions to the real world.

As each board is returned, distribute addi-tional copies of the game rules to the groups as well as copies of the discussion ques-tions, as shown in Table 3. Students gener-ate much more thorough discussions and papers if they have access to the rules and questions in written form. After the game boards are returned, students should remain in their groups and begin talking. Initially, direct their attention toward what events transpired and what emotions were stimu-lated during the game. This initial informa-tion leads to a discussion of empathy and explanations for the events and emotions. In some cases, the discussion encompasses an analysis of the realism of the game and gen-eralizations from it to the real world, but primarily, discussions tend to focus on

278 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY

FOUR ES DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Events Who won? Who lost? Who owned the most land, monopolies, houses, and hotels? Who spent the most time in jail? What rules were made before and after the revolu-tion? Did any players suggest rules to the upper class ruling elite before or after the revolution? Who was self-interested, greedy, or cruel? Who was philanthropic? Who got even? Who took pride in and flaunted their status? Who complained or begged? Who played to win? Who played to survive? Who tried to make any alliances between class members? Did anyone attempt to cheat? What kind of jokes or humor was being used?

Emotions Who felt angry or frustrated? Who felt greedy or energized? Who felt tired or bored? Who felt happy? Who felt sad? Who felt guilty? Who felt complacent? How did each player feel before and after the revolutionary switch? Which emotions felt the most intense? Whose emotions felt the most intense?

Empathy How did each player experience the game before and after the revolutionary switch? How might the middle and working class players have experienced the game differ-ently if they had been involved in the revolutionary switch? How did each player ex-perience the game before and after the upper class ruling elite player was allowed to make and change the rules? What rules would the middle and working class players have made had they been given that power?

Explanations Why did players feel what they felt? What messages were they receiving from those emotions about the rules, the players, luck, fairness, and what we value? Identify the hierarchies of power, prestige, and privilege in the game and what elements point to them. What emotions were associated with experiencing unfairness within the rules? What emotions were associated with experiencing power, prestige, and privilege within the rules? Identify social institutions within the social structure (rules) and examples of how they limited playing the game. What events pointed to successful individualism or bad luck within the social structure? Who has vested interest in keep-ing the rules the way they are? Who do the rules (social structure) encourage to cheat? Why didnt anyone make the rule to stop playing the game altogether?

Table 3. Discussion Questions for USA Stratified Monopoly

-

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY 279

events, emotions, empathy, and explana-tions.

Writing Assignment In addition to continuing the discussion on paper, the writing assignment allows stu-dents to thoroughly process the final ele-ments: everyday and employment. Writing assignments are an effective part of learn-ing, because teachers can write extensive remarks to each student, allowing a new level of communication and understanding to emerge (Petranek 1994; Petranek, Corey, and Black 1992). As they leave the class-room, each student takes a copy of the writ-ing assignment as shown in Table 4. It is

important to return these papers to students promptly with comments written on them. This enhances learning and allows teachers to develop better rapport and stronger edu-cational bonds with individual students (McKeachie 1999). This process allows teachers the opportunity to address any is-sues students may still have about their emotional reactions to the game, individual-ism, social change, or their relations to the social-class stratification system. This proc-ess also gives the teacher valuable feedback with which to assess the value of the game as an instrument for teaching about social class stratification.

SECTION INSTRUCTIONS

Events Write a paragraph summarizing the major events of the game. Emotions Write a paragraph summarizing the major emotions of the game. Empathy Write a paragraph summarizing the distribution of power, privilege, and prestige

within the four positions of the game. Explanations Write a paragraph or two summarizing the theoretical explanation for the events,

emotions, and differential statuses within the game. Everyday Write a few paragraphs discussing the following questions. Identify ways the game

felt realistic or unrealistic. Identify what rules of the game represented reality in the United States. Identify what rules did not represent reality and how might they have been more realistic. Identify what additional rules might make the game more realis-tic. What other changes might you suggest to make the simulation more realistic?

Employment Write several paragraphs discussing the following questions. How does the sociologi-cal literature connect with the experiences of this game? For example, how does the game connect to the writings of Marx, Weber, Adams, Martineau, or status attain-ment theories? Identify what other institutions within the social structure perpetuate these inequities in power, prestige, and privilege. Identify how those institutions might be expressed within the simulation game. What do we say we value in our soci-ety? What does our behavior and emotions tell us that we value? What stereotypes do we have about social class stratification and how did they play out in the game and how do they get realized in our everyday lives? How did we conform to the rules in the game and how does this conformity get realized in our everyday lives? How does social structure limit your life chances? Who perpetuates the system and how? Give examples major and minor acts of individual agency and activism. Give examples of major and minor social changes. Give examples of how race and ethnicity interact with social class stratification. Give examples of how sex and gender interact with social class stratification. Give examples of how sexuality, religion, age, and ability interact with social class stratification. What messages about social class stratification do the regular rules to Monopoly suggest? Are those messages accurate and credi-ble? In whose interests were those rules made? How do those rules and these rules relate to the American Dream? Who does the structure encourage to cheat?

Table 4. Instructions for the Writing Assignment for USA Stratified Monopoly

-

ASSESSMENT USA Stratified Monopoly makes for an ex-tremely memorable experience that serves well as a referent for ongoing learning. Even introverted and uninvolved classes engage in lively discussions after playing, and often submit thought-provoking papers. Every time I use this game, the opening session of the next class period is devoted to students sharing the discussions they had about the game with friends, family, and intimates since we played. Students regu-larly refer to game throughout the semester. For example, when writing about hetero-centrism later in the semester, one student wrote, Its just like in the game we played. The deck is stacked against them. The sys-tem is designed to punish them for not fol-lowing the normonly this time the norm is to be heterosexual.

Students are able to generalize from the game to their everyday lives. One student wrote about the working- and lower-class players in her group, They were just doing their best, trying to survive, and barely hanging on. It made me think of all the women standing in line at walmart [sic] buying generic laundry soap and cleaning supplies. They all look so tired and beaten down. Students also frequently comment that this exercise made them realize how other seemingly benign games, shirts, but-tons, billboards, bumper stickers, posters, and stickers have political messages in them about class, race, or sex.

Students are able to identify individualism within the structure of the game. During the discussions, it becomes apparent that some-times the working- or the lower-class player is more successful than the structural limita-tions would predict; sometimes the middle-class player has a streak of bad luck and does quite poorly. Sometimes the upper-class ruling-elite player makes altruistic rules or doesnt take advantage of their power. One student wrote, Its like Oprah. She wasnt born into class privilege but she has it now, but not because she is so much more special than the rest of us. She just got

lucky, like winning the lottery. Shoving her in my face all the time only pushes me to buy more lottery tickets. Another wrote, Sometimes the rich get unlucky toojust look at OJ. He may have beat prison, but his life will never be the same non-stop party it was before. There is a positive relationship between class size and ability to expose individualism within the game. The more games in play, the better the chance that some of them will deviate from the expected outcome, allowing for discussions about luck, chance, and random outcomes. The fewer the games in play, the less likely these deviations will occur, making it more difficult to discuss individualism with stu-dents. In these cases, it is possible to dis-cuss the possibilities of what would happen if 100 games were in play at the same time.

Students develop empathy through the game. One student wrote that their groups upper-class ruling-elite player became sick with power. It was like watching this nor-mal person get put in a position that made him go absolutely insane. Another student wrote about a working-class player, She was like a hamster in a wheel. She just kept running like mad going nowhere fast. One student wrote about the lower-class player, It was obvious that her best chance to stay in the game was to stay in jail. It was so unfair. Another student wrote about the middle-class player, I could see how irri-tated she was with all our complaining. She didnt want to rock the boat to try to help us either. She was doing just fine and wasnt about to risk losing her advantage to show any support for us.

Students regularly discuss their values and the stereotypes that arose in the game. They often comment that they showed little mercy on players going to jail. One student wrote, Every time I landed on his property when he was in jail I would gloat that I didnt have to pay him any rent. Another said, We just kept coming up with other trashy crimes to accuse him of . . . . I didnt think about it until we talked afterwards, but we really do think awful things about poor peo-ple being criminals. Another student

280 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY

-

wrote, I never realized how easy it was just to believe they were lazy and deserved it. It is easier to believe I deserve privileges because of luck and they didnt because the dice just didnt like them.

Students learn about social change in the game and in their everyday lives. Many students mention their majors and how one day they will be in positions to either repro-duce inequality or change things. Often stu-dents suggest ways that they will contribute to social change through their future ca-reers. In the game they make choices and rules; then through discussion and their papers, they generalize those actions to real life examples like welfare capitalism, uni-versal healthcare, living wages, democracy, socialism, and communism. Students also realize how they perpetuate social-class stratification and inequality. One student wrote, Even though I hated him, I still wanted TO BE him. I didnt hate the power, privilege, or prestigeI just hated him for having it instead of me.

Students critically examine themselves and society. One student wrote, The regu-lar rules of monopoly represent the Ameri-can Dream. The rules to USA Stratified Monopoly represents [sic] the way it really is but we talk to each other and act like we live in the regular rules of the game. We still buy into the dream that the old rules apply in the real world, but they sure dont. Another student shared, I never thought I blamed people for their misfor-tunes in life, but I guess I do believe that people get out of life what they put into it. I guess thats my middle class upbringing talking for me. Time to rethink that one!

CONCLUSION

USA Stratified Monopoly is a flexible, dy-namic simulation game that effectively teaches students about social class stratifica-tion. This game successfully meets its learn-ing objectives and can be a very powerful educational tool. It is well suited for class-rooms with up to 60 students and can be played successfully in 50-minute class ses-

sions. As beneficial as this simulation game may

be, USA Stratified Monopoly has limita-tions. Classroom space and mobility con-straints are unavoidable. While it is possible to complete in 50 minutes, the depth of cov-erage decreases, making 75 minutes or more ideal. There is also the cost and stor-age of the games themselves. If these pre-vent your use of the game, teams of stu-dents may be used instead of individuals. However, it is easier to discuss individual-ism when multiple games are used. Future modifications of the game might better inte-grate race/ethnicity, sex/gender, and sexual-ity. In addition, no individual exercise can undo a minimum of 18 years of socializa-tion.

Teachers must be aware of the emotional risks to students before using this game. USA Stratified Monopoly can bring out some intense emotions and reactions from students, and it is our responsibility to safely facilitate their learning experiences. In his paper, one criminal justice major from a military family wrote, Give up your citizenship and leave if you hate it here so much. Splevin correctly warns teachers, If you are afraid to dapple with emotions, the step to skip is not debriefing but the experiential activity in the first place (1979:17). Teachers who want their stu-dents to play USA Stratified Monopoly but who do not feel confident about their ability to safely and effectively facilitate the game should ask another teacher to do it. As re-searchers, our ethical guidelines insist we do no harm to research participants because their right to be is more important than our right to know. As teachers, we should fol-low a similar ethical guideline to do no harm to student participants because their right to be is more important than our right to teach.

REFERENCES

Brezina, Timothy. 1996. Teaching Inequality:

A Simple Counterfactual Exercise. Teaching Sociology 24(2):218-24.

Coleman, James S., Samuel A. Livingston, Gail

USA STRATIFIED MONOPOLY 281

-

282 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY

M. Fennessey, Keith J. Edwards, and Steven J. Kidder. 1973. The Hopkins Games Pro-gram: Conclusions from Seven Years of Re-search. Educational Researcher 2(8):3-7.

Corrado, Marisa, Beth Merenstein, Davita Silfen Glasberg, and Melanie R. Peele. 2000. Playing at Work: The Intersection of Race, Class, and Gender with Power Structures of Work and Production. Teaching Sociology 28(1):56-66.

Davis, James A., Richard Dukes, and William A. Gamson. 1981. Assessing Interactive Modes of Sociology Instruction. Teaching Sociology 8(3):313-23.

Davis, Nancy J. 1992. Teaching about Inequal-ity: Student Resistance, Paralysis, and Rage. Teaching Sociology 20(3):232-8.

Glasberg, Davita Sifen, Barbara Nangle, Flor-ence Maatita, and Tracy Schauer. 1998. Games Children Play: An Exercise Illustrat-ing Agents of Socialization. Teaching Sociol-ogy 26(2):130-9.

Goldsmid, Charles A. and Everett K. Wilson. 1980. Passing on Sociology: The Teaching of a Discipline. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association/Teaching Resources Center.

Greenblat, C. S. 1971. Simulation, Games, and the Sociologist. American Sociologist 6(1):161-4.

Greenblat, C. S., and R. D. Duke. 1981. Princi-ples and Practices of Gaming Simulation. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Jessup, Michael M. 2001. Sociopoly: Life on the Boardwalk. Teaching Sociology 29(1):102-9.

McKeachie, Wilbert J. 1999. McKeachies Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and The-ory for College and University Teachers. 10th ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Miller, Margaret A. 1992. Life Chances Ex-

ercise. Teaching Sociology 20(4):316-20. Petranek, Charles F. 1994. A Maturation in

Experiential Learning: Principles of Simula-tion & Gaming. Simulation & Gaming 25(4):513-23.

Petranek, Charles F., Susan Corey, and Rebecca Black. 1992. Three Levels of Learning in Simulations: Participating, Debriefing, and Journal Writing. Simulation & Gaming 23(1):174-85.

Randel, Joseph, Barbara A. Morris, C. Douglas Wetzel, and Betty V. Whitehill. 1992. The Effectiveness of Games for Educational Pur-poses: A Review of Recent Research. Simu-lation & Gaming 23(2):261-76.

Ross, Lee. 1977. The Intuitive Psychologist and his Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attri-bution Process. Pp. 174-221 in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 10, edited by L. Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press.

Splevin, George. 1979. Directed Discovery in Debriefing. SIMAGES --:3:17-21.

Tiemann, Kathleen, Karen Davis, and Eide Terri. 2006. What Kind of Car Am I? An Exercise to Sensitize Students to Social Class Inequality. Teaching Sociology 34(3):398-403.

Wetcher-Hendricks, Debra and Wade Luquet. 2003. Teaching Stratification with Crayons. Teaching Sociology 31(3):345-351.

Edith M. Fisher developed USA Stratified Monop-

oly as an instructor of womens studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where she received her PhD in sociology. She is an active advocate for victims of violence in her university and local community. Her current research interests focus on sexual violence, feminist research methods, and issues related to teaching. Her current teaching inter-ests focus on feminist theory and methodology, sex and gender issues, and social problems.