Urban Sanitation

-

Upload

akhil-ajit -

Category

Documents

-

view

112 -

download

1

Transcript of Urban Sanitation

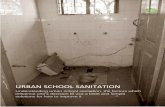

Urban sanitation- slum improvement and housing for the poor

Sophia Badsha

Urban sanitation

sanitation is defined as safe disposal of human excreta including its safe

confinement treatment disposal and associated hygiene practices. Sanitation is

also depend on other elements like environmental sanitation along with the

management of drinking water supply

Sanitation in India is becoming more and more problematic . There are so many

attributable factors responsible for this situation . Sanitation it self is in

crisis ,its not only in India this is through out the world . 2.6 billion people

worldwide - 40% of the world's population - do not have a toilet. Yet, despite

the fact that 5,000 children die every day from diarrhoeal diseases, there has

been no political action on the issue2.the millennium development goals clearly

stated the importance of water and sanitation the fact is water and sanitation is

the most neglected and most off-track of the UN millennium development

goals2. Developing countries like India and sub Saharan African countries the

cost of not investing in sanitation and water are huge - infant deaths, lost work

days, and missed school are estimated to have an economic cost of around $38

billion per year, with sanitation accounting for 92% of this value3. In the world

for every 15 seconds a child was dyeing of water related diseases.

What is the situation in India?

India stands second place amongst the worst places in the world for sanitation5

• Around 40 million people reside in slums, without adequate water and

sanitation

• India will have 41% of its population living in cities and towns by 2030 i.e.

over 575 million people from present 286 million. But they can't have water

and sanitation till we recognize their existence.

27.8% of Indians, i.e. 286 million people or 55 million households live in urban

areas - projections indicate that the urban population would have grown to

331 million people by 2007 and to 368 million by 2012. 12.04 million (7.87 %)

Urban households do not have access to latrines and defecate in the open. 5.48

million (8.13%) Urban households use community latrines and 13.4 million

households (19.49%) use shared latrines. 12.47 million (18.5%) households do

not have access to a drainage network. 26.83 million (39.8%) households are

connected to open drains. The status in respect of the urban poor is even worse.

The overall sanitation coverage in India in 2005-2006 is 44.6% . The rural

sanitation is 26% and urban sanitation is 84.6% only .however field studies

shown that very low usage of latrines in both rural and urban areas . 74% of

people in rural India still don't have a toilet and in urban it is 16%7. There is a

gradual change in sanitation coverage in India and the trend is increasing over

the past two decades . But if it will take place in the same pace it may take

another 200 years to get a toilet for every Indian.

The real situation may even worse than the above facts. Water and sanitation are

basic amenities and responsibility of the government.

Factors that are responsible for poor sanitation in India

India is a unique country with different geographic and climatic conditions. This

is the major factor to impact any decision or policy implementation at central

level.

India is urbanizing very fast and along with this, the slum population is also

increasing. India's urban population is increasing at a faster rate than its total

population. With over 575 million people, India will have 41% of its population

living in cities and towns by 2030 AD from the present level of 286 million and

28%. However, most of them are not having basic facilities like drinking water

and sanitation. Among the urban poor, the slum dwellers are the poorest. The

very definition of slums points at acute drinking water and sanitation crisis for

the slum dwellers. Slum in India is defined as a cluster inside urban areas

without having water and sanitation access. Slum population is constantly

increasing: it has doubled in the past two decades. The current population living

in slums in the country is more than the population of Britain. India's slum-

dwelling population rose from 27.9 million in 1981 to over 40 million in 2001.

As per the 2001 census of India, 640 towns spread over 26 states and union

territories have reported existence of slums. This means one out of every four

persons reside in slums in our cities and towns. The NSSO survey in 2002 has

identified 51688 slums in urban areas of which 50.6% of urban slums have been

declared as "notified slums". This growing slum population and the lack of

basic facilities will badly impact on India's overall target achievement in water

and sanitation sector4 in view of the above situation Govt. of India had

launched The National sanitation policy .

The specific goals of the policy were

• Awareness Generation and Behaviour Change

• Open Defecation Free Cities

• Integrated City-Wide Sanitation

Key Sanitation Policy Issues

In order to achieve the above Vision, following key policy issues must be

addressed:

• Poor Awareness: Sanitation has been accorded low priority and there is poor

awareness about its inherent linkages with public health.

• Social and Occupational aspects of Sanitation: Despite the appropriate legal

framework, progress towards the elimination of manual scavenging has shown

limited success, Little or no attention has been paid towards the occupational

hazard faced by sanitation workers daily.

• Fragmented Institutional Roles and Responsibilities: There are considerable

gaps and overlaps in institutional roles and responsibilities at the national,

state, and city levels. Lack of an Integrated City-wide Approach: Sanitation

investments are currently planned in a piece-meal manner and do not take into

account the full cycle of safe confinement, treatment and safe disposal.

• Limited Technology Choices: Technologies have been focused on limited

options that have not been cost-effective, and sustainability of investments

has been in question.

• Reaching the UN-served and Poor: Urban poor communities as well other

residents of informal settlements have been constrained by lack of tenure, space

or economic constraints, in obtaining affordable access to safe sanitation. In

this context, the issues of whether services to the poor should be individualized

and whether community services should be provided in non notified slums

should be addressed. However provision of individual toilets should be

prioritized. In relation to "Pay and Use" toilets, the issue of subsidies

inadvertently reaching the non-poor should be addressed by identifying

different categories of urban poor.

• Lack of Demand Responsiveness: Sanitation has been provided by public

agencies in a supply- driven manner, with little regard for demands and

preferences of households as customers of sanitation services.

March 23, 2011

Water woes- The Hindu

Despite rapid technological progress and economic growth, close to 900 million

people the world over do not use drinking water from improved sources and

over 2.6 billion lack access to decent sanitation facilities. This indefensible

public failing, which is conspicuous in the developing world, comes with

tremendous economic and social costs. Safe drinking water and basic sanitation,

as United Nations organisations have often emphasised, help prevent water-

related diseases. Specifically when it comes to diarrhoea, which kills 1.6 million

annually, improved water supply reduces morbidity by 20 per cent while

improved sanitation cuts it by 37.5 per cent. The indirect benefits of providing

access to drinking water to households, such as the time saved by women and

children — who are often carriers of this precious commodity from source —

are reflected, for example, in better school attendance. The debilitating effect of

the lack of sanitation facilities is seldom appreciated. A World Bank study

placed the total economic impact of inadequate sanitation in India at Rs.2.44

trillion (6.4 per cent of India's GDP in 2006). Three ongoing UN initiatives

spotlight the importance of water and sanitation: the Millennium Development

Goals, the Water for Life Decade (2005-2015), and the annual World Water

Day (March 22) which had “Water for Cities” as the theme this year.

India, its urban areas included, is a laggard, especially in sanitation. More than

37 per cent of urban India's human excreta is unsafely disposed of, posing

significant health hazards. The country is also home to the world's largest

number of persons who defecate in the open (665 million persons of a global

total of 1.1 billion). Shockingly, 4,66,853 elementary schools did not have toilet

facilities, going by the data for 2009. The crisis looming over urban India is best

revealed by a central government survey between December 2009 and March

2010. In this exercise, which ranked the 423 class-I cities according to metrics

set by the National Urban Sanitation Policy, not a single one was eligible to be

in the top slot of a “green city” (which needed to score at least 90 per cent) and

only four were “blue cities” (67 per cent to 90 per cent). With 189 cities

categorised as “red” (less than 33 per cent), and the remaining 230 in the

“black” zone, it is evident that India has a long way to go in providing this basic

infrastructure, which not only offers minimum dignity to life but is the

elementary requirement for a healthy society. High economic growth rates, even

if they are sustained, do not such a society make.

THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, March 1, 2012

318 houses for the urban poor

Urban Affairs Minister P.K. Kunhalikutty on Wednesday inaugurated the

Kalladimukham slum improvement project of the City Corporation, being

implemented under the Basic Services for Urban Poor (BSUP) scheme.

Mayor K. Chandrika presided over the function. V. Sivankutty, MLA, was the

chief guest. Deputy Mayor G. Happykumar; Corporation standing committee

chairpersons Shajida Nasser, Palayam Rajan, V.S. Padmakumar, S.

Pushpalatha, Vanaja Rajendrababu and P. Shyamkumar; United Democratic

Front leader in the council Johnson Joseph; and BJP leader Ashok Kumar were

present.

In two phases

As many as 318 housing units would be constructed under the Rs.10.5-

crore project, in two phases. The project will be implemented by

COSTFORD.

Of the total housing units, 105 are for families belonging to Scheduled Castes

and Scheduled Tribes categories, and 213 units for general category families.

The project coming up in around nine acres in Kalladimukham colony also

includes construction of a community hall, study centre, library, anganwadi,

television kiosk, roads, storm-water drainage, biogas plant, health club,

streetlights, drinking water supply and so on.

The first phase of the project, that includes construction of 105 houses, is

expected to be completed in a year.Although a section of colony residents had

initially protested against the inclusion of beneficiaries from general category in

the project, the differences had been sorted out recently with the intervention of

City Mayor K. Chandrika.

‘Issues resolved'

The agitators had demanded that the benefits of the project should be provided

only to deserving families from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes as the

land for the housing project had been bought using the Special Component Plan

(SCP) fund allotted for Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes development

projects.

“The agitators were under the wrong impression that the Corporation had

bought the land Kalladimukham using SCP funds alone. But the Corporation

had, in fact, bought the land using both SCP and general fund. So beneficiaries

from both categories can avail of the benefits of the project. The Mayor had

recently convened a meeting to convince this to the agitators following which

the issue was resolved,” said Corporation works standing committee chairman

V.S. Padmakumar.

He added that the steps for preparing the beneficiary list for the project would

begin soon. Families from slum areas in 15 wards adjoining Kalladimukham

will be rehabilitated with the project.

Pucca Houses for Poor, Slum Improvement Underway in 34 MP Cities

March 9, 2010 Visionmp.com news service

Bhopal – Implementation on 37 schemes for construction of pucca houses for

the poor and improvement of slums is going on at a fast pace in 34 cities of

Madhya Pradesh. The cost of these initiatives under Integrated Housing and

Slum Improvement Project is Rs 27035.99 lakh.

The scheme has been implemented by merging National Slum Development

Programme and Valmiki Ambedkar Yojana under which 18503 houses are

being constructed in 37 cities of the state. Under the scheme, 80 per cent funds

are allocated by the Union government and 8 to 10 per cent grant is given by the

state government. The beneficiary’s share is only 10 to 12 per cent.

The Union government has fixed the cost of a housing unit at Rs 80 thousand,

which sometimes is insufficient for practical purposes. Efforts are underway to

resolve the matter following which the pace of construction will gather

momentum.

Under the scheme, 4576 houses are being constructed for the urban poor in

Gwalior city and 2108 in Khandwa under two schemes.

Pucca houses are also being built for the urban poor in Ganj Basoda, Lateri,

Vidisha, Sironj, Kurwai, Berasia in Bhopal division and Khujner in Rajgarh

district.

In Khandwa, Depalpur, Pansemal and Dewas in Indore division, 2724 houses

will be constructed.

In all, 2182 houses will be constructed in Katni, 966 in Balaghat, 651 in

Narsinghpur, 240 each in Patan and Barela, 104 in Shahpura, 140 in Majholi

and 104 in Damoh. Besides, 192 houses will be constructed in Indore division’s

Betma and Gautampura, 240 in Petlawad in Jhabua, 153 in Itarsi, 180 in

Mandideep, 297 in Hoshangabad, 192 in Orchha, 833 in Burhanpur and 167 in

Jaora.

In all, 480 houses will be constructed in Sagar, 500 in Chhindwara city and 267

and 461 houses respectively in Mehgaon and Saunsar in the same district.

Conclusion:

Despite some successes and the support of the World Bank and the UN-

HABITAT, not all believe slum upgrading is the ideal choice for solving the

problem of slums. In fact, there are a number of different players – such as local

politicians – who would like to see the status quo concerning slums stay the

same. Yet beyond petty local politics, there are major problems with the slum

upgrading approach, some of which have to do with the very nature of many

slums themselves. For example, in order to lay infrastructure for slum

upgrading projects, the governments inevitably have to buy land. However, this

raises tremendous difficulties when trying to figure out which land to buy, since

slums are (by definition) so densely populated that some houses are literally on

top of one another, making it difficult to bring any sense of organization to the

areas.

The second problem with slum upgrading stems from the fact that land

ownership is not clear. Many times slum dwellers are either transient dwellers

or have informal arrangements with the community around them. As a result, as

many governments try to go in and establish land rights, difficulties ensue. The

World Bank has attempted to separate land ownership deeds and the actual

development of infrastructure, but this creates whole new problems of its own.

After all, if ownership is not clearly established, tenants are often unlikely to

pay for the utilities they receive as a result of the slum upgrading projects.

Developing nations cannot afford to provide free utilities for an extended period

of time, so this creates a huge problem for attempts at slum upgrading.

Another criticism of slum upgrading is that the infrastructure built as a result

must be maintained. In fact, because many governments try to cut the costs of

slum upgrading via lower quality infrastructure, subsequent costs of

maintenance are often higher. In fact, a minority (47 percent) of the World

Bank’s urban projects are considered sustainable. Thus, for many of the

projects, the one-time cost is not enough: slum upgrading projects are long-term

commitments unless they are made with the ability to recover costs through

revenue.

Finally, there is difficulty in establishing community and group efforts to bring

about real improvement within the slum community. Slums are areas in which

violence and conflict are rampant – yet often outside of the scope of knowledge

of the government. Because community participation can significantly help the

people who are actually doing the slum upgrading by shedding light on

community issues that would otherwise hamper slum upgrading efforts, not

engaging the community (either from a lack of effort or inherent lack of ability)

makes slum upgrading much more difficult