Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection ......Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection...

Transcript of Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection ......Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection...

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis How local governments in the Upper Neuse River Basin can cooperatively generate a sustainable revenue stream to implement watershed protection strategies

August 2012

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | ii

About the Environmental Finance Center The Environmental Finance Center is part of a network of university-based centers that work on environmental issues, including water resources, solid waste management, energy, and land conservation. The EFC at UNC partners with organizations across the United States to assist communities, provide training and policy analysis services, and disseminate tools and research on a variety of environmental finance and policy topics. The EFC at UNC is dedicated to enhancing the ability of governments to provide environmental programs and services in fair, effective, and financially sustainable ways.

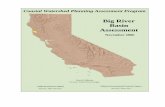

Acknowledgements Researched and written by Jeff Hughes, Jon Breece, and Lauren Patterson. This report was made possible by funding from the Conservation Trust for North Carolina through a grant from the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number NRCS 68-3A75-9-128. Support was also provided by the Environmental Protection Agency’s Targeted Watershed Grants Program (WS-96493108-0). Editorial assistance was provided by Lisa Creasman and Erin Weeks. The analysis would not have been possible without the data and resources available through the National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis, the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the North Carolina Department of the State Treasurer. This report is a product of the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Findings, interpretations, and conclusions included in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of EFC funders, the University of North Carolina, the School of Government, or those who provided review. Cover image courtesy of Google depicts the branching of the Eno and Little Rivers north of Falls Lake.

© 2012 Environmental Finance Center

School of Government Knapp-Sanders Building, CB# 3330

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330

www.efc.unc.edu

All rights reserved

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | iii

TA B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 1

2 Water Quality in the Upper Neuse River Basin and the Importance of Boundaries: Applying the

Revenueshed Concept .......................................................................................................................... 3

2.1 Introduction to the Upper Neuse River Basin (UNRB)................................................................ 4

2.2 Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (UNCWI) ............................................................................ 6

2.3 Revenueshed Concept ................................................................................................................ 7

2.3.1 What is a revenueshed? .................................................................................................. 7

2.3.2 What are the advantages of the revenueshed analysis framework? ............................. 7

2.3.3 How can revenuesheds be used as a tool for watershed protection? ........................... 8

2.4 Integrating Revenuesheds with North Carolina State Legislation for Watershed Protection ... 9

3 Revenueshed Analysis Applied to the Upper Neuse River Basin ....................................................... 11

3.1 Drinking Water Utilities ............................................................................................................ 14

3.1.1 Water Supply in the UNRB ............................................................................................ 15

3.1.2 Drinking Water Utilities as a Revenueshed ................................................................... 20

3.1.3 Water Demand Projections ........................................................................................... 23

3.1.4 Projected Demands for Durham and Raleigh – Revenueshed Implications ................. 24

3.2 Point Source (Municipal Wastewater Discharge in the UNRB) ................................................ 28

3.3 Non-point Discharge – Catchment Basins and Stormwater Management .............................. 33

3.3.1 Stormwater at the Federal and State Scale .................................................................. 33

3.3.2 Stormwater at the Local Government Scale ................................................................. 33

3.3.3 Municipal Non-Point Source Impacts in the UNRB ....................................................... 35

3.3.4 County Non-Point Source Impacts in the UNRB ........................................................... 40

3.4 Comparing Annual Revenue Trends for Water, Wastewater and Stormwater Utilities .......... 44

4 Watershed Protection Fees on water bills ......................................................................................... 47

5 UNCWI Dashboard .............................................................................................................................. 49

5.1 Calculations: ............................................................................................................................. 50

5.2 Dashboard Scenarios ................................................................................................................ 52

5.3 Ongoing applications of the revenueshed concept: ................................................................. 54

6 Appendix I — The Cost of Conservation: Property Tax Revenues and Land Protection .................... 55

6.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 56

6.2 State Law and Property Tax Valuation ..................................................................................... 56

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | iv

6.3 Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 57

6.4 Results ...................................................................................................................................... 57

6.5 Conclusion: Not all land is created equal ................................................................................. 65

6.6 Potential for “spill-over” impacts ............................................................................................. 65

7 Appendix II — The Capitalization of Conservation: Land Protection and Effects on Tax-Assessed Values of

Adjacent Properties ............................................................................................................................ 66

7.1 Existing Research ...................................................................................................................... 66

7.2 Research Pertinent to Triangle Region ..................................................................................... 67

7.3 Limitations ................................................................................................................................ 70

8 Appendix III — Implementation ......................................................................................................... 71

8.1 Potential Inter-Institutional Arrangements .............................................................................. 71

8.2 Interlocal Agreements .............................................................................................................. 71

8.3 “Project” managed by a Regional Planning Entity/Council of Government ............................ 73

8.4 Not-for Profit ............................................................................................................................ 74

8.5 Soil and Water Conservation Districts ...................................................................................... 76

9 Literature Cited ................................................................................................................................... 78

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | v

List of Tables Table 1: Percent of jurisdictions located inside the UNRB ......................................................................................... 12

Table 2: Matrix of local government services ............................................................................................................. 14

Table 3: Water supply intakes in the Upper Neuse River Basin .................................................................................. 17

Table 4: Surface water supply attributes of the reservoir and WTPs ......................................................................... 19

Table 5: Water utility rates for customers inside the city limits. ................................................................................ 20

Table 6: Monthly residential and non-residential bill given average water use. ........................................................ 21

Table 7: Estimated and reported 2010 revenue by water utility ................................................................................ 22

Table 8: Population in UNRB counties from 2000 to 2009 ......................................................................................... 23

Table 9: Water demand projections in the UNRB ....................................................................................................... 23

Table 10: Projected supply and demand for the City of Durham ............................................................................... 25

Table 11: Projected supply and demand for the City of Raleigh................................................................................. 26

Table 12: Attributes of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants discharging to Falls Lake ...................................... 29

Table 13: Wastewater utility rates for customers inside the city limits ..................................................................... 30

Table 14: Monthly residential and non-residential bill given average wastewater use ............................................. 31

Table 15: Estimated and reported 2010 revenue by wastewater utility. ................................................................... 32

Table 16: Stormwater utility rates in the UNRB ......................................................................................................... 38

Table 17: Estimated and reported 2010 revenue by stormwater utility. ................................................................... 39

Table 18: Three years of AFIR total revenue by water sales ....................................................................................... 45

Table 19: Three years of AFIR total revenue by wastewater sales ............................................................................. 45

Table 20: Three years of AFIR total revenue by stormwater fees .............................................................................. 45

Table 21: Central Arkansas Water Watershed Protection Fees .................................................................................. 47

Table 22: Project specific revenue scenarios for the City of Durham. ........................................................................ 53

Table 23: Dedicated revenue stream generated for watershed protection by all utilities participating in a uniform rate

increase of $0.05 per kgal. ................................................................................................................................... 53

Table 24: Real property valuation in Durham and Orange Counties .......................................................................... 57

Table 25: Value of high priority lands in present use ................................................................................................. 59

Table 26: What will be impacted -- the land value of high-priority lands not in present-use .................................... 63

Table 27: Scenarios defined ........................................................................................................................................ 63

Table 28: Scenario results ........................................................................................................................................... 64

Table 29: Changes in county property tax revenues .................................................................................................. 64

Table 30: Impact on adjacent properties of encumbering properties with conservation easements ....................... 67

Table 31: Valuation of lands within 400 meters and one mile of high-priority lands ................................................. 68

Table 32: Elasticity and one mile buffer applied to the properties adjacent to the easement .................................. 69

List of Figures Figure 1: Location of Upper Neuse River Basin and 2010 Impaired Water Bodies status ............................................ 5

Figure 2: Schematic of Falls Lake reservoir storage ...................................................................................................... 6

Figure 3: Boundaries present within the study area..................................................................................................... 7

Figure 4: Revenueshed concept Venn diagram ............................................................................................................ 8

Figure 5: North Carolina river basins and additional water quality regulations ........................................................... 9

Figure 6: County and municipal boundaries in the UNRB........................................................................................... 12

Figure 7: Land cover in and around the UNRB in 2006 ............................................................................................... 13

Figure 8: Population density for the Upper Neuse in 2000 ........................................................................................ 13

Figure 9: Water utilities in the Upper Neuse River Basin ........................................................................................... 15

Figure 10: Water source locations and corresponding sub-watershed in the UNRB ................................................. 16

Figure 11: The watershed for each reservoir is delineated. ....................................................................................... 17

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | vi

Figure 12: The watershed for each reservoir and jurisdictional boundaries. ............................................................. 18

Figure 13: Moving water from the reservoir to the served jurisdictions. ................................................................... 19

Figure 14: Monthly residential and non-residential bill divided by the average use.................................................. 22

Figure 15: Population growth in the UNRB from 2000 to 2009 .................................................................................. 23

Figure 16: Average daily demand (MGD) and population served for the City of Durham ......................................... 24

Figure 17: Average daily demand (MGD) and population served for the City of Raleigh ........................................... 25

Figure 18: Projected supply and demand for the City of Durham .............................................................................. 26

Figure 19: Projected supply and demand for the City of Raleigh ............................................................................... 27

Figure 20: Municipalities serviced by the Raleigh Water Utility ................................................................................. 27

Figure 21: Receiving water bodies for municipal wastewater systems in the UNRB. ................................................ 29

Figure 22: Wastewater utilities in the Upper Neuse River Basin ................................................................................ 31

Figure 23: Monthly residential and non-residential bill divided by the average use.................................................. 32

Figure 24: Diagram illustrating the responsibilities of local and state governments to administer stormwater programs in

North Carolina. Figure is from Georgoulias (2010). ............................................................................................. 34

Figure 25: Revenue generated by stormwater utilities in 2008 in North Carolina ..................................................... 35

Figure 26: Stormwater and non-point discharge impacts from Roxboro to Falls Lake. ............................................. 36

Figure 27: Stormwater and non-point discharge impacts from Hillsborough to Falls Lake. ....................................... 37

Figure 28: Stormwater and non-point discharge impacts from Durham to Falls Lake. .............................................. 38

Figure 29: Stormwater and non-point discharge impacts from Butner and Creedmoor to Falls Lake. ...................... 39

Figure 30: Stormwater and non-point discharge impacts from Raleigh and Wake Forest to Falls Lake. ................... 40

Figure 31: Non-point source runoff for Person County .............................................................................................. 41

Figure 32: Non-point source runoff from Granville County ........................................................................................ 42

Figure 33: Non-point source runoff from Franklin County ......................................................................................... 42

Figure 34: Non-point source runoff for Orange County ............................................................................................. 43

Figure 35: Non-point source runoff for Durham County ............................................................................................ 43

Figure 36: Non-point source runoff for Wake County ................................................................................................ 44

Figure 37: Total water sales for utilities from 2008 to 2010 ....................................................................................... 46

Figure 38: Total wastewater sales for utilities from 2008 to 2010 ............................................................................. 46

Figure 39: Raleigh Dashboard showing the proposed rate increase and resulting impact ........................................ 52

Figure 40: Uniform rate increase for all utilities and local jurisdictions in the UNRB ................................................. 54

Figure 41: Acres under conservation easement in Orange County, NC...................................................................... 55

Figure 42: Healthy Forests-identified "high-priority" parcels in UNRB ....................................................................... 56

Figure 43: Land area vs. valuation .............................................................................................................................. 57

Figure 44: Valuation, Durham County (January 1, 2010) ............................................................................................ 58

Figure 45: Valuation, Orange County (January 1, 2010) ............................................................................................. 59

Figure 46: Land status negatively impacting Durham County tax rolls ....................................................................... 61

Figure 47: Land status negatively impacting Orange County tax rolls ........................................................................ 62

Figure 48: Impact as percent of county totals ............................................................................................................ 65

Figure 49: Adjacency effects: Durham and Orange, 2010 .......................................................................................... 68

Figure 50: Adjacency impacts: Durham County, 2010 ................................................................................................ 69

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 1

1 Executive Summary

The Environmental Finance Center (EFC) was hired by the Conservation Trust for North Carolina (CTNC) as part of the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities Healthy Watersheds through Healthy Forests grant: Protecting the Future of the Upper Neuse River Basin (UNRB). CTNC facilitates the Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (UNCWI) on behalf of the region’s six land trusts. In 2010, UNCWI developed a model to assess high-priority parcels for land conservation, particularly forests, to pro-actively protect the health of the watershed in the UNRB. The role of the EFC, and the content of this report, was to examine the potential for cooperatively generating a sustainable revenue stream among local governments in the UNRB to purchase conservation easements and implement other watershed protection strategies. One of the main challenges of watershed protection is that jurisdictional and watershed boundaries rarely align. This generates questions about who is responsible for, and who should pay for, watershed protection. We have developed and applied the concept of a revenueshed, which is the area within which revenue is generated for watershed protection, to address these challenges by (1) cultivating accountability, (2) generating discussions among local governments, and (3) developing interactive financial tools to assist in policy decision-making. This report also discusses strategies for implementing watershed protection financing as a sustainable revenue stream. Examples of policy implications highlighted in the report:

1. Hydrological connectedness binds residents up- and downstream. Upstream communities’ land-use decisions, stormwater runoff, and wastewater treatment plants have a significant impact on water quality in the UNRB. Despite this obvious connection, there are limited examples of local governments “connecting” their revenue-generating authority in ways that mirror hydrological boundaries.

2. Watershed restoration regulations promote the “polluter pays” principle, resulting in less

attention towards the “beneficiary pays” principle.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 2

Downstream communities located outside of the UNRB use water impounded in the watershed’s reservoirs. This water has helped fuel regional growth and now supports a population exceeding 450,000 (predominantly in the city of Raleigh). These downstream communities do not directly impact the water quality and quantity flowing into Falls Lake, but they are heavily invested in protecting their water supply watershed. While current watershed protection legislation in North Carolina targets those local governments within the watershed, the beneficiaries of the watershed can provide substantial assistance to watershed protection and should not be overlooked.

3. Leveraging the resources necessary for comprehensive restoration requires jurisdictional collaboration. The population in the UNRB and adjacent areas has grown rapidly in the last few decades and has placed greater stress on water resources. Growing populations require advance, proactive planning to increase water security. Collaboration between local jurisdictions within and adjacent to the UNRB is critical to effectively manage and protect water resources to meet growing demand. Restoration and preservation financing that is done piecemeal fails to tap into the economies of scale and beneficiary pooling advantages of a more comprehensive approach.

4. North Carolina law provides the freedom to implement watershed protection taxes and pay

for it through utility fees (N.C. General Statutes §160A-314, §162A-9, §162A-49). Water utilities often expand outside of municipal boundaries and can draw from their full customer base. Stormwater utilities have a smaller customer base, since they are limited to those customers located inside the municipal boundary. Stormwater fees are collected to minimize the impact of a city on its watershed and are often used to protect the water flowing downstream. Raleigh has expanded their water bill to include a watershed protection fee. Water utilities are an ideal conduit through which to leverage watershed protection fees because they focus on protecting their own water supply source. The City of Durham also approved a watershed protection fee in 2011 (one cent per 100 cubic feet) and dedicates $500,000 of its water utility revenue toward watershed protection.

5. Watershed protection often costs less than watershed restoration.

It costs less money to protect a watershed now than to attempt to restore a watershed to health in the future. A previous study estimated the average willingness-to-pay for watershed protection in a western North Carolina watershed at $139 per year per residential household (Kramer, 2002). Most examples of explicit watershed protection fees cost less than $20 per year.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 3

2 Water Quality in the Upper Neuse River Basin and the Importance of

Boundaries: Applying the Revenueshed Concept The Upper Neuse River Basin (UNRB) is the most upstream watershed (Hydrologic Unit Code 8) in the Neuse River Basin, North Carolina (Figure 1). The UNRB is 770 mi2 and outflows through the Falls Lake Reservoir. Approximately 670,000 people living within and outside of the basin depend on surface water supplies within the UNRB for their drinking water (SDWIS 2011). The UNRB boundaries include part or all of thirteen separate political jurisdictions with different land use, water-related utilities (water, wastewater, and stormwater), and responsibilities. The Falls Lake Reservoir and several streams draining into the Reservoir have been designated as impaired water bodies. As a result, the state of North Carolina passed a comprehensive set of rules and regulations in 2010 that will require a wide range of locally-implemented pollution control and mitigation measures. Water systems face complex challenges that cut across multiple jurisdictional boundaries. The 2010 Interagency Climate Change Progress Report noted several components of a comprehensive water resource management plan that are essential to effectively address these complex issues (White House Council, 2010). Many of the components listed below are being proactively addressed by the State of North Carolina and the UNCWI Endowment for Forestry and Communities grant:

1. Apply an ecosystem-based approach that simultaneously strives to protect ecosystem services from being degraded and restores ecosystem services that are already negatively impacted. The goal of this project is to protect healthy working forests that contribute to healthy watersheds, while also working to mitigate and restore those sections of the watershed that currently have degraded water quality.

2. Build strong partnerships that can leverage existing efforts and the knowledge of a wide range of stakeholders across jurisdictional boundaries and geographic scales. UNCWI is working with multiple jurisdictions and stakeholders in the UNRB to build partnerships dedicated to protecting the health of the watershed.

3. Maximize mutual benefits by using strategies that support ecosystem needs, as well as the needs of multiple jurisdictions and stakeholders in the watershed. UNCWI, in collaboration with the EFC, explored ways to generate dedicated sustainable watershed protection funds that can be used to improve water quality through land conservation and other measures. Spreading the cost of watershed protection across those living in the UNRB and to those relying on the basin for their water supply needs provides a large revenue source at more amenable costs for households.

4. Continually evaluate the effectiveness of already implemented strategies to improve water quality, and be prepared to adapt strategies if the desired outcomes are not being met. This component has been built into the phased sections of the Falls Lake Rules (discussed below).

In an effort to better understand the UNRB water system and to help inform and support local government initiatives, the Environmental Finance Center (EFC) at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill has developed an analytical approach to examining watershed protection challenges. We refer to this approach as a revenueshed analysis, which is used to explore the complex relationships between environmental services, local government jurisdictions, and watershed boundaries. The revenueshed analysis provided the framework to identify and analyze potential revenue streams for watershed protection, with the ultimate goal of providing information that generates discussion and assists in the development of a dedicated watershed protection revenue stream.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 4

Our revenueshed analysis is not designed to be a full “eco-system” services study, but rather as a pragmatic snapshot that is primarily bounded by existing local government services such as stormwater management and water treatment. For example, our analysis does not include economic assessments of less tangible and more difficult revenue capture services such as the value of natural capital providing goods (water, fish, forests) and services (flood protection, recreation clean water, forests removing nutrients and sediment, biodiversity, etc). As a result, the base line characterization and potential revenue solutions outlined in the analysis simply address existing governmental services such as stormwater, land use planning, and drinking water provision. This section provides the background on the UNRB and describes the attributes and advantages of the revenueshed approach.

2.1 Introduction to the Upper Neuse River Basin (UNRB)

Historically, the Neuse River Basin has had water quality problems due in particular to excess nitrogen, which increases algal growth and eutrophication. In 1995, poor water quality and high rainfall resulted in a die-off that killed millions of fish. The NC General Assembly responded in 1997 by passing House Bill 1339, also known as the Neuse Nutrient Sensitive Waters Rules (NSWR), with the goal of reducing nitrogen loads by thirty percent. A major component of this effort has been the establishment of riparian buffers, which are forested or vegetated stands that protect nearby water bodies from neighboring land-use impacts. Conserving forests adjacent to streams allows trees to denitrify shallow groundwater (sub-surface runoff) prior to entering the water body. A NCDWQ (2011) study estimated that the amount of nitrogen reaching the Neuse River would increase by 17% if half of the current riparian areas were lost, thereby highlighting the importance of prioritizing land conservation as a strategy for watershed protection. In addition, forested riparian buffers slow water velocity and reduce the amount of sediment that is deposited into a stream via stormwater runoff by as much as 61 to 97%, depending on the width of the riparian buffer (Gilliam et al., 1997). The UNRB covers 770 square miles of the upper reaches of the Basin, covering portions of six counties and eight municipalities. While the UNRB was included in the Neuse NSWR, during the 2008 EPA sampling period, 46% of sampled UNRB streams were impaired and placed on the 303(d) list (approximately 60% of all streams were sampled; EPA 2010; Figure 1). The main source of impairment for streams was poor biological / ecological integrity. In Falls Lake, high Chlorophyll A levels, which serve as a surrogate for excessive nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations, were the basis for the listing of Falls Lake as impaired in 2008. Falls Lake was also found in violation of turbidity standards above Interstate 85. The poor water quality of Falls Lake, which releases water downstream to the Neuse River, resulted in the NC General Assembly passing Senate Bill 1020 to add additional requirements to SB 981 for water quality protection in the Upper Neuse River Basin. The final rules have been termed the Falls Lake Rules and were implemented in January 2011. The Falls Lake Reservoir was constructed in 1981 by the US Army Corps as a multi-purpose dam for flood control, water supply, recreation, fish and wildlife enhancement, and the augmentation of low flows for water quality control in the Neuse River Basin. Falls Lake is the only significant water supply for the City of Raleigh’s Water System (~475,000 residents). There are eight additional water supply reservoirs located in the UNRB.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 5

Figure 1: Location of Upper Neuse River Basin and 2010 Impaired Water Bodies status

Falls Lake plays a crucial role in the Neuse River Basin as a water supply and water quality control reservoir (Figure 2); however, managing the reservoir for both water quantity and quality has been challenging. The water quality conservation pool is designed to meet water quality standards for both impounded water and the water released downstream of the dam. While our research was designed specifically to address watershed protection for water quality in Falls Lake, it is recognized that degraded water quality limits the amount of water available for consumption. For this reason, the City of Raleigh has been a strong advocate for protecting the water quality of Falls Lake in order to protect their main water supply.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 6

Figure 2: Schematic of Falls Lake reservoir storage (Water Wiki 2011)

Water quality protection has been mandated by the federal government through laws such as the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA) in order “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters” (33 U.S.C §1251(a)). Under section 303(d) of the CWA, each state is responsible for identifying those waters for which a water body exceeds the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of different pollutants as established by the State. A TMDL is the maximum amount of a pollutant that a water body can receive and still safely meet water quality standards. Where a water body fails to comply with TMDL standards, it is placed onto the 303(d) list and the state or local jurisdiction is required to prioritize resources and work toward improving the water quality. According to Perciasepe (1997), “if we are to achieve clean water everywhere, though, we must continue to build capacity to identify remaining problem areas and fix each problem on a watershed-by-watershed basis. The TMDL program is crucial to success because it brings rigor, accountability, and statutory authority to the process.” The Neuse River Basin is one such watershed that has continued to be plagued by water quality problems despite the CWA.

2.2 Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (UNCWI)

This work was funded by the Conservation Trust for North Carolina (CTNC) as part of the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities Healthy Watersheds through Healthy Forests grant. The Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (UNCWI) was formed in 2005 as a partnership between seven non-profit organizations (Conservation Trust for North Carolina, Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association, Eno River Association, Tar River Land Conservancy, Triangle Greenways Council, Triangle Land Conservancy and Trust for Public Land) with the goal of protecting the drinking water sources in the UNRB through upstream land conservation. UNCWI, which is facilitated by the Conservation Trust for North Carolina, has received project funding from a number of sources, including the City of Raleigh. As of December 2010, for every dollar the City of Raleigh has invested, UNCWI has leveraged almost $11 of land value (fifty-one projects acquisitioned for $54 million [Personal Comm. with CTNC Conservation Programs Director L. Creasman, April 6, 2011]). Land conservation focuses on protecting or restoring forests as a means of absorbing excess nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus), trapping sediments (reducing turbidity), and controlling stormwater runoff. Our analysis therefore focuses primarily on land conservation based watershed protection; however, many of the communities we’ve studied could benefit from other types of watershed protection measures, such as best management practices and education.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 7

2.3 Revenueshed Concept

The EPA identifies a “watershed planning approach” as one of the four pillars of sustainable infrastructure. Many watershed plans, despite receiving wide support, have yet to be implemented due to a lack of financial resources. Tapping into local government revenue is essential to achieving watershed protection goals.

2.3.1 What is a revenueshed?

We define a revenueshed as the geographic area within which revenue is generated for a specific purpose. Here, a revenueshed describes the area within which revenue is generated for watershed protection.

2.3.2 What are the advantages of the revenueshed analysis framework?

Jurisdictional boundaries were developed to meet social, economic, and/or political needs, rather than to coincide with hydrologic boundaries. As a result, jurisdictional boundaries (sources of revenue for watershed protection) often do not match watershed boundaries (Figure 3). This leads to:

Multiple jurisdictions being responsible for financing watershed protection in a single watershed. The result is often a free-rider problem whereby all jurisdictions want the benefit of clean water but nobody wants to pay for it. Pooling revenue from these communities for efforts that exceed their jurisdictional boundaries is difficult. The consequence is that water quality is not directly addressed until it approaches a crisis point where action is necessary.

Single jurisdictions become responsible for watershed protection in multiple watersheds. All jurisdictions have limited financial resources; therefore, decisions have to be made regarding how much money is invested in each watershed. In addition, each watershed may have different legislative requirements for water quality and/or watershed protection.

Water quality and quantity are affected by decisions made upstream. Who is responsible for ensuring the quality and quantity of water available for downstream users? The upstream impacting jurisdictions, the downstream benefitting jurisdictions, or both?

Figure 3: Boundaries present within the study area. B) River basins are spatially non-congruent with county boundaries. C) Durham municipal and utility boundaries do not overlap with county or watershed boundaries.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 8

2.3.3 How can revenuesheds be used as a tool for watershed protection?

Griggs (1999) stated that the main challenge for water resource management in the future will be institutional, particularly regarding questions about who is responsible for, and who should pay for, water resource management. We have applied the revenueshed concept to address these challenges along three main avenues (Figure 4):

Figure 4: Revenueshed concept Venn diagram

1. Revenuesheds are used to cultivate accountability by providing an unbiased documentation of

the baseline revenue generated by each jurisdiction from water, wastewater, and stormwater fees within a specific watershed. Additional sources of revenue may be considered – such as property taxes and nutrient impact fees. These sources of revenue can be explored with respect to the proportion of the jurisdiction within the watershed, per capita, per impaired streams, etc.

2. Revenuesheds are used to generate discussions among jurisdictions directly related to the watershed. Data are visually displayed through maps to provide the geographic context of the watershed, impaired streams, legislation, jurisdictions, utilities and associated revenue.

3. Revenuesheds provide a means to develop scenarios to assist in policy decision-making and fund

watershed protection. This includes examining how to collaboratively and intentionally finance a project or generate a dedicated revenue stream. This is particularly important if there is unclear leadership or responsibility. Commonly, this ambiguity is the result of a negative externality where personal or community decisions have a broader impact on the watershed as a whole. For example, land conversion or poor agricultural practices are land use decisions that impact water quality in surrounding streams. Downstream water users are impacted by the cumulative effect of decisions that lead to water quality degradation, but it is unclear who is directly responsible and whether the polluters or the water users are responsible for improving water quality to the level required for its desired use. A combination of interactive financial tools and maps are used to promote the implementation of actual policies that lead to sustainable watershed protection financing.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 9

2.4 Integrating Revenuesheds with North Carolina State Legislation for Watershed

Protection

In the mid-1980s, the Pamlico River estuary had excess nutrients in the water that led to algal blooms and stressed biota. North Carolina responded by designating the entire Tar-Pamlico River Basin as Nutrient Sensitive Waters (NSW) in 1990 and has worked towards developing basin-wide strategies to reduce the nutrient load entering the estuary. This approach to watershed protection can be labeled a “problemshed” approach, whereby the specific water body is the problem and the watershed draining into that region is the problemshed (Gerlak, 2006). In the above example, the excess nutrients in the Pamlico River estuary were the problem and the Tar-Pamlico River Basin was the problemshed.

Figure 5: North Carolina river basins and additional water quality regulations. The City of Durham is located within the boundaries of the Neuse Rules and the Jordan Lake Rules. Only municipalities with a population greater than 10,000 are shown.

This approach of identifying a water body that requires protection and then passing legislation for the jurisdictions in the upstream watershed to improve the water quality of runoff entering the water body has been taken by the State of North Carolina on multiple occasions since the 1990s (Figure 5). The two most recent and controversial watershed rules were passed for Jordan Lake in 2009 and Falls Lake in 2011. The controversy highlights two challenges to the problemshed approach:

1. First, the problemshed only looks to the upstream jurisdictions as a resource to improve water quality to the benefit of downstream users. This is particularly problematic for those jurisdictions who receive no benefit from water quality improvements (e.g. Durham is affected by Jordan Lake and Falls Lake Rules but neither lake is a main water supply for Durham). Revenuesheds address this issue by considering both the polluters and the beneficiaries as being viable financing options for working towards sustainable watershed protection. The different jurisdictions are responsible for collaborating and discussing which options are feasible for their particular situation.

2. Second, serious implementation discussions and actions to improve water quality often occur only after a problem has been identified and mandatory legislation enacted. The process is reactive and likely more expensive than if proactive measures to improve water quality had

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 10

been taken. The revenueshed approach provides an alternative means to examine jurisdictions and watersheds simultaneously and to proactively engage discussions on how to generate sustainable revenue for watershed protection. The goal is for sustainable watershed protection funding and implementation to occur prior to water quality impairment.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 11

3 Revenueshed Analysis Applied to the Upper Neuse River Basin

Cultivate Financial Accountability and Generate Discussions In this section we will outline the process of creating a revenueshed to cultivate financial accountability and generate discussions between jurisdictions. We will examine what jurisdictions are directly tied to the UNRB, in particular Falls Lake. We will explore the revenueshed characteristics for “impactors” (those jurisdictions located upstream of Falls Lake that impact water quality), and “benefactors” (those jurisdictions benefiting from improved water quality downstream) with the understanding that these designations are rarely clear-cut and communities often are both impactors and benefactors of watersheds.

Data Sources (see Inventory.xls) for details Spatial and tabular data were collected for the UNRB. Wherever possible, tabular data were attached to spatial data for visualization. Spatial data includes natural, political, utility and parcel boundaries. Natural boundaries include watersheds, land use, and water bodies (NC One Map). EPA stream ratings (NCDWQ 2011) are tabular data that were attached to spatial data for visualization (e.g. Figure 1). Jurisdictional boundaries include counties, municipalities, parcel, conservations easements, and census data (NC One Map and local jurisdiction’s GIS). Utility boundaries include water, wastewater, and stormwater service areas. Additional spatial data for utilities include the location of water intakes and discharges, interconnections between utilities, water supply watersheds, and stormwater regulatory boundaries. This data came from a variety of sources including NCGIA, NCDENR, NCDWQ, and NCLWSP. Lastly, utility information, property tax rates, and government budgets were obtained from the respective agency and available annual financial information reports (AFIR) from the State Treasurer.

Overview of the Upper Neuse River Basin (UNRB) The UNRB includes all or parts of six counties, eight municipalities, seven water utilities, seven wastewater utilities, and two stormwater utilities (Table 1; Figure 6). Jurisdictions located within the UNRB are termed “impactors” because their land use decisions directly impact water quality. Services provided by impactors are more directed toward deterring negative impacts to the watershed (such as wastewater and stormwater utilities). On the other hand, the role of the benefactors is more related to using a resource in the watershed (such as drinking water utilities). Jurisdictions located downstream of the UNRB that benefit from improved water supply quality are termed “benefactors.” Jurisdictions range on this continuum from the role of mostly impactor (e.g. Town of Roxboro) to mostly benefactor (e.g. City of Raleigh). The City of Durham is both an impactor and benefactor (its water supply source is located inside the UNRB). Again, all jurisdictions impact and benefit from watersheds.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 12

Table 1: Percent of jurisdictions located inside the UNRB

County Area (mi2) % in UNRB Municipality Area (mi2) % in UNRB

Durham 299 69% Durham 106 44%

Franklin 495 2% None ---

Granville 536 25% Butner 14 100%

Creedmoor 4 100% Stem 1 100%

Orange 402 49% Hillsborough 5 100%

Person 404 32% Roxboro 6 50%

Wake 856 12% Raleigh 143 1%

Wake Forest 14 7%

Total 2,992 293

Figure 6: County and municipal boundaries in the UNRB

Approximately 58% of the watershed is forested, 18% is agricultural and 11% is developed. Figure 7 shows the location of recent development pressure within and directly outside the UNRB, particularly along the southern boundary from Durham to Raleigh. The highest population densities in the UNRB are located inside the Durham municipality (Figure 8). Most areas have population density less than 200 people per mile. Stormwater from Durham is located downstream of all water supply watersheds except Falls Lake (Figure 10).

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 13

Figure 7: Land cover in and around the UNRB in 2006 (NLCD data from the USGS)

Figure 8: Population density for the Upper Neuse in 2000 (population per square mile)

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 14

Below we will explore three types of utilities and their relationship to watershed protection in the UNRB. First, we look at drinking water utilities, which are focused on protecting their water supply. Second, we look at wastewater utilities, which focus on discharging clean, treated water back into the watershed and meeting federal regulations. Third, we look at stormwater utilities that focus on mitigating and improving the water quality of non-point source discharge, as well as restoring impaired water bodies. All three types of utilities provide the opportunity to offer expertise and monetary resources for watershed protection.

We developed a matrix to guide your understanding of which utilities have an investment in watershed protection for the UNRB based on their capacity to impact or benefiting from the watershed (Table 2). This table highlights the important role that drinking water utilities can play in protecting their water supply source through a dedicated revenue stream, such as watershed protection fees. Currently there are only two dedicated watershed protection fees in the UNRB: Raleigh’s newly passed watershed protection fee ($0.10 per kgal of drinking water consumed) and the City of Durham’s stormwater utility. In addition, the City of Durham recently passed a new watershed fee ($0.01 per ccf) in addition to setting aside $500,000 of their annual drinking water revenue for watershed protection.

Table 2: Matrix of local government services that directly impact or benefit from the UNRB Watershed

Drinking Water

Utility Wastewater

Utility Stormwater

Management Services

Creedmoor X .

Durham X X X

Hillsborough X X .

Orange-Alamance X .

Raleigh* X

Roxboro .

SGWASA X X . . Stormwater management program – not a separate Stormwater Utility *If this matrix was created only for Falls Lake – Raleigh would be the only water utility marked with an X.

3.1 Drinking Water Utilities

The UNRB intersects seven water utilities (Figure 9), although the City of Roxboro does not use water from the UNRB and the City of Durham uses water from both the UNRB and the Cape Fear River Basin. In this section, we will first examine the sub-watersheds, reservoirs, and water treatment plants in the UNRB. Next we will provide basic information for all drinking water utilities which have customers in the UNRB and / or withdraw source water from the UNRB.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 15

Figure 9: Water utilities in the Upper Neuse River Basin

3.1.1 Water Supply in the UNRB

The UNRB contains seven sub-watersheds draining into Falls Lake (Figure 10). There are seven water treatment plants (WTP) accessing nine reservoirs (Table 3). Four of these plants are located within the Eno River watershed. Corporation Lake is the Reservoir for Orange-Alamance, and the remaining three reservoirs are used to manage Hillsborough’s water supply. Hillsborough draws directly from the Ben Johnston reservoir. The remaining sub-watersheds each contain a single WTP, except Ellerbe Creek, which has no WTPs. Falls Lake is the most downstream reservoir and contains all of the upstream water supply watersheds (Figure 11).

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 16

Figure 10: Water source locations and corresponding sub-watershed in the UNRB

The purpose of visualizing the water supply watershed for each reservoir is to understand that land use and water resource management decisions made upstream have a direct impact on both water quantity and quality in the reservoir. Figure 11 andFigure 12 highlight the directional impact that land use and water resource decisions have on each respective water supply reservoir, as well as which jurisdictions are located upstream. For example, decisions made in the City of Roxboro will have an impact on water resources at Lake Michie and Falls Lake. Hillsborough, Durham, and Wake Forest are located downstream of all water supply reservoirs except Falls Lake (so they only impact the water quality in Falls Lake). Lake Orange, Hillsborough, Corporation Lake, Ben Johnston, Little River Reservoir, and Lake Holt do not have any municipalities located within their watershed, with only the counties in those reservoirs having the potential for influencing land use decisions.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 17

Table 3: Water supply intakes in the Upper Neuse River Basin

Utility Stream Reservoir Water Treatment

Plant (WTP) Use Type

Raleigh Neuse River Falls Lake E.M. Johnson Regular

Durham

Flat River Lake Michie Williams Regular

Little River Little River Lake Brown Regular

Eno River

Emergency

Orange-Alamance

Eno River Corporation Lake Orange-Alamance Regular

Hillsborough

Eno River Lake Ben Johnston Hillsborough Regular

East Fork of the Eno River

Lake Orange Hillsborough Emergency

West Fork of the Eno River

Hillsborough / West Fork Reservoir

Hillsborough Regular

Creedmoor Ledge Creek Lake Rogers Creedmoor Regular

South Granville Water and

Sewer Authority Knap of Reeds Creek R.D. Holt Butner Regular

Figure 11: The watershed for each reservoir is delineated. Shading darkens farther downstream. Arrows show flow direction and size reflects relative contribution. Reservoir size is relative to the raw water supply held in the reservoir (millions of gallons).

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 18

Figure 12: Same as Figure 11, except jurisdictional boundaries are overlaid to highlight which reservoir watersheds are impacted by each jurisdiction

The most recently available (2006 and 2009) local water supply plans (LWSP) for each water utility contain information regarding the raw water supply storage of the reservoir and the available raw water supply on a daily basis (Table 4). In 2007, Raleigh and Durham were utilizing 76% and 93% of their daily available raw water supply from the UNRB (Durham has additional water supply from the Cape Fear River Basin). There is an increased risk for water scarcity as utilities approach an equivalent water demand to supply ratio. On May 12, 2010 Raleigh opened the Dempsey E. Benton WTP with a capacity of 20 MGD from Lake Benson and Lake Wheeler, and plans to expand the E.M. Johnson WTP capacity to withdrawal up to 120 MGD from Falls Lake. In addition to the Little River and Lake Michie reservoirs, the City of Durham has access to Teer Quarry, Jordan Lake, as well as emergency interconnection contracts with Orange Water and Sewer Authority (OWASA), Chatham County, Cary, Orange-Alamance, and Hillsborough. Figure 13 shows the main service area for each water supply reservoir. Hillsborough, Butner and Creedmoor drinking water utilities serve customers that are only located inside the UNRB. Water withdrawn by Orange-Alamance serves customers in Orange County (29% of service population), but most of the water is sent outside of the UNRB to Alamance County. Water withdrawn by Durham serves customers inside of the UNRB (44% of service population), but 56% of their service population is located in the Cape Fear River Basin. Durham discharges approximately half of its wastewater to the Cape Fear and the other half to the UNRB. Roxboro does not use water from the UNRB for drinking water, but uses water from and discharges water to the Roanoke River Basin.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 19

Table 4: Surface water supply attributes of the reservoir and WTPs (source: LWSP)

Reservoir

Average Inflow Water

Supply (MGD)

Usable Impounded

Water Supply (MG)

2007 Ave Daily

Withdrawal (MGD)

Water Utility Permitted Capacity (MGD)

Ratio Withdraw/

Supply *

Lake Orange 0.08 478

1.14 Hillsborough 3 45% Hillsborough 1.80 786

Ben Johnston 0.68 24

Corporation 0.37 19 0.3 Orange Alamance

0.90 42%

Lake Rogers 0.44 215 0.3 Creedmoor 0.46 30%

Lake Holt 11 2,200 2.4 SGWASA 7.50 25%

Lake Michie 19 3,300 14.0 Durham - Williams

22

60% Little River 18 4,900 20.4

Durham - Brown

30

Falls Lake 67 10,033 51.0 Raleigh 86 68%

*Ratio withdraw / supply was taken from LWSP and reflects purchase agreements and GW sources as well

Figure 13: Moving water from the reservoir to the served jurisdictions

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 20

3.1.2 Drinking Water Utilities as a Revenueshed

One of the main concerns with all nine of the reservoirs in the UNRB is that the water quality does not deteriorate to the point of being unusable or prohibitively expensive to treat. The cities of Raleigh and Durham have the largest demand for water in the UNRB (Figure 13). There has not been a clear trend in water demand for most of these water utilities over the last decade. One confounding factor is the presence of two severe hydrologic droughts that resulted in mandatory water conservation and technological improvements. Thus, while the population has continued to increase, water demand does not show a clear increasing trend for most utilities.

Water utilities charge different rates for their services (Table 5). All utilities have updated rates within the last year. Data was obtained from the local water supply plan (LWSP), annual financial data report (AFIR), and an EFC rate survey. Utilities have a monthly fixed base charge and a rate charge per unit of water consumed. Hillsborough, Roxboro, and South Granville Water and Sewer Authority (SGWASA) have a uniform rate. The remaining utilities have an increasing block structure, meaning that as more water is consumed the cost per unit of water increases. Durham and Raleigh charge their customers in units of hundred cubic feet (ccf) while the remaining utilities use units of a thousand gallons (kgal). One ccf is 0.748 kgal. This information was incorporated into the dashboard for the UNRB to produce scenarios for the average impact on a household and the total revenue generated with an increase in the base or rate charge. Southern Granville Water and Sewer Authority is abbreviated to SGWASA. All utilities charged a uniform rate for wastewater. Franklin County was excluded since such a small portion of customers are served in the UNRB. Table 5: Water utility rates for customers inside the city limits. Rates were converted to kgal for comparison.

Residential Accounts Non-Residential

Accounts

Water Utility Base

Charge ($)

In Base

Charge (kgalt)

Current Rate ($/kgal)

Ave Water

Use (kgal / Month)

FY 2010 #

Accounts

Ave Water

Use (kgal / Month)

FY 2010 #

Accounts

Last Update

Creedmoor $12.87 0

$5.54 (<5 kgal) $7.86 (>5 kgal)

3.5 1,916 13.0 140 2010

Durham**† $5.35 0

$2.30 (<1.5 kgal) $3.46 (1.6-3.7 kgal) $3.80 (3.8-6 kgal)

$4.96 (6-11.2 kgal)

$7.43 (>11.2 kgal)

4.0 75,801 37.4 8,954 2011

Hillsborough $21.75 3 $7.25 4.5 4,729 26.4 448 2010

Orange-Alamance

$18.00 0

$4.00 (<20 kgal) $5.50 (>20 kgal)

3.9 3,255 15.1 152 2010

Raleigh†† $5.24 0

$3.05 (<3 kgal) $5.08 (3-7.5 kgal) $6.78 (>7.5 kgal)

4.4 152,956 23.6 14,221 2010

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 21

Roxboro* $8.24 0 $3.62 3.9 4,028 33.7 704 2010

SGWASA $22.70 2 $3.60 2.5 3,228 43.6 252 2010

* Utility drinking water source is outside the UNRB **Utility drinking water source is inside and outside the UNRB † Durham: Current Rate (per CCF) = $1.72 (<2 ccf), $2.59 (2-5 ccf), $2.84 (5-8 ccf), $3.71 (8-15 ccf), and $5.56 (>15 ccf), Average Use – see Table 6. †† Raleigh: Current Rate (per CCF) = $2.28 (<4 ccf), $3.80 (4-10 ccf), and $5.07 (>10 ccf) , Average Use – see Table 6

Average Customer Bill The monthly bill for residential and non-residential customers was calculated for each utility based on the reported average use (Table 6). The average monthly bill is not directly comparable since each utility has a different average monthly water use. To incorporate the fixed, rate, and use into a comparable value we divided the average monthly bill by the average use to get a dollars paid per kgal of water consumed (Figure 14). This also enables comparison between residential and non-residential customers. Table 6: Monthly residential and non-residential bill given average water use. The average monthly bill divided by the average

use provides the amount paid (fixed and rate included) per kgal of consumption.

Residential Non-Residential

Water Utility Ave Use kgal (ccf)

Average Bill ($)

Bill / Use ($/kgal)

Ave Use kgal (ccf)

Average Bill ($)

Bill / Use ($/kgal)

Creedmoor 3.5 (4.7) $32.09 $9.17 13.0 (17.4) $103.14 $7.93

Durham** 4.0 (5.3) $17.41 $4.35 37.4 (50.0) $147.35 $3.94

Hillsborough 4.5 (6.0) $32.63 $7.25 26.4 (35.3) $191.40 $7.25

Orange-Alamance 3.9 (5.2) $33.52 $8.59 15.3 (20.5) $79.20 $5.18

Raleigh 4.4 (5.9) $21.58 $4.90 23.6 (31.5) $98.13 $4.16

Roxboro* 3.9 (5.2) $22.40 $5.74 33.7 (45.1) $130.35 $3.87

SGWASA 2.5 (3.3) $24.57 $9.83 43.6 (58.3) $172.46 $3.96 * Utility drinking water source is outside the UNRB **Utility drinking water source is inside and outside the UNRB

Comparing the bill/use we find that Creedmoor, Hillsborough and SGWASA pay more money per unit of water consumed. Raleigh and Durham overall pay the least per kgal of water consumed. Hillsborough is the only utility that has an equal amount paid for kgal by both residential and non-residential customers. All remaining water utilities charge residents a higher amount per kgal than non-residential customers.

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 22

Figure 14: Monthly residential and non-residential bill divided by the average use. This value accounts for both fixed and rate charges to enable comparison between water utilities.

Annual Revenue Generated by the Drinking Water Utility

The average monthly bill for residents was multiplied by the total number of reported accounts and multiplied by 12 (months in a year). The same calculation was done for the non-residential customers. The results were summed together to estimate the 2010 total water utility revenues (Table 7). The municipal water utilities have AFIR data available that reports the annual revenue from water sales. This data was compared with our 2010 estimated annual revenue as a check. Some discrepancy is anticipated since we are using average and not actual use for all customers. We anticipate underestimating revenues due to the increasing block rate structure for many of these utilities. Our estimated value was 7 to 18% less than the reported water sales for all utilities except Raleigh, which were an estimated 8% higher than reported in AFIR.

Table 7: Estimated and reported 2010 revenue by water utility. Orange-Alamance and SGWASA do not have AFIR data.

Residential Non-Residential

Water Utility Ave Bill

($) Number Accounts

Ave Bill ($)

Number Accounts

2010 Estimate Annual

Revenue

2010 AFIR Reported Revenue

Percent Difference

Creedmoor $32.09 1,916 $103.14 140 $911,088 $1,025,728 -11%

Durham** $17.41 75,801 $147.35 8,954 $31,668,808 $38,044,534 -17%

Hillsborough $32.63 4,729 $191.40 448 $2,880,654 $3,531,295 -18%

Orange-Alamance

$33.52 3,255 $79.20 152 $1,453,752 No Data No Data

Raleigh $21.58 152,956 $98.13 14,221 $56,355,567 $52,061,800 8%

Roxboro* $22.40 4,028 $130.35 704 $2,183,923 $2,339,325 -7%

$9.17

$4.35

$7.25 $8.59

$4.90 $5.74

$9.83

$7.93

$3.94

$7.25 $5.18

$4.16 $3.87

$3.96

$0

$2

$4

$6

$8

$10

$12

$14

$16

$18

Creedmoor Durham Hillsborough Orange-Alamance

Raleigh Roxboro SGWASA

Mo

nth

ly B

ill D

ived

by

Ave

rage

Use

($

/kga

l) Non-Residential

Residential

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 23

SGWASA $24.57 3,228 $172.46 252 $1,473,340 No Data No Data * Utility drinking water source is outside the UNRB **Utility drinking water source is inside and outside the UNRB

3.1.3 Water Demand Projections

The following section addresses the potential impact of population growth revenue generation for water utilities in the UNRB. The Upper Neuse River Basin has a growing population (Table 8 and Figure 15). The growing population has resulted in additional strain on this region’s water resources. The remainder of the revenueshed section will focus on the potential impact of increased water stress on the City of Durham and Raleigh as demand is projected to grow (Table 9).

Table 8: Population in UNRB counties from 2000 to 2009 (source: US Census Bureau)

County Jul-00 Jul-03 Jul-06 Jul-09 2000 to 2009 growth

Durham 224,635 236,753 249,253 269,706 20.1%

Franklin 47,610 51,932 55,447 60,088 26.9%

Granville 48,844 52,362 54,117 57,639 18.0%

Orange 116,049 117,575 122,084 129,083 11.2%

Person 35,746 36,532 37,077 37,667 5.4%

Wake 633,517 701,347 792,940 897,214 41.2%

Figure 15: Population growth in the UNRB from 2000 to 2009

Table 9: Water demand projections in the UNRB (MGD; Source is LWSP 2006 to 2009)

Utility 2010 2020 2030 Projected increase in water demand from 2010 to 2030

Creedmoor 0.30 0.41 0.57 91%

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 24

Durham 28.2 32.0 35.8 27%

Hillsborough 1.3 1.8 2.0 55%

Orange-Alamance 0.66 0.69 0.73 11%

Raleigh 59.6 78.4 94.0 58%

SGWASA 2.7 3.0 3.2 19%

3.1.4 Projected Demands for Durham and Raleigh – Revenueshed Implications

The City of Durham’s residents impact, but do not directly benefit from improved raw drinking water quality in Falls Lake, while the City of Raleigh is a beneficiary of the water quality in Falls Lake. Both cities have experienced significant population growth from 2000 to 2008 (Durham at 22% and Raleigh at 37%); which has placed stress on available water supplies and contributed to water pollution. While the trend in population has consistently grown in these two municipalities, the average daily water demand has fluctuated due to drought, changes in technology, water conservation measures, etc. The overall trend for water demand is increasing for this area, but not at the rate previously projected (Figure 16 and Figure 17). If the trend in water demand can be increasingly decoupled from population growth, it will reduce the water stress in this region and delay the need for further water supply development.

Figure 16: Average daily demand (MGD) and population served for the City of Durham (source: AFIR, Durham (2009), LWSP)

31

28

27 27

28 28

27

26

28

165

181

205 209

215

222 228

234

140

160

180

200

220

240

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Po

pu

lati

on

Ser

ved

Th

ou

san

ds

Ave

rage

Dai

ly D

eman

d (

MG

D)

Average Daily Demand

Population Served

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 25

Figure 17: Average daily demand (MGD) and population served for the City of Raleigh (source: AFIR, Raleigh (2007), LWSP)

Information regarding projected supply and demand is presented below. The baseline for this information was taken from the 2007 LWSP and updated capacity improvement reports. The City of Durham has direct access to 37 MGD from Lake Michie and the Little River Reservoir, in addition to 10 MGD of allocation space from Jordan Lake (Table 10). The drought from 2007 and 2008 resulted in accelerated water supply capacity enhancement developments by the City of Durham that was not anticipated prior to the drought (Morrison 2011). The City of Durham developed Teer Quarry to add an additional 7 MGD to their water supply. Durham also accessed 2 of its 10 MGD allocation at Jordan Lake through an interconnection with the Town of Cary for a total available water supply of 46 MGD. It is assumed that Durham will gain access to all 10 MGD of Jordan Lake by 2050. The water demand for Durham is anticipated to increase by 45% from 2010 to 2050, and its 2010 projected demand is similar to the recorded average demand. In spite of the population increase, the City of Durham anticipates meeting demand through 2050 (Figure 18). The City of Durham is currently looking toward the Cape Fear River Basin for additional water supplies. Future water supply alternatives that would impact Falls Lake involve expanding the capacity of Lake Michie and developing a new water supply on either Flat River or Little River (DCP, 2010).

Table 10: Projected supply and demand for the City of Durham

City of Durham 2007 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

Surface Water Supply 37 37 37 37 37 37

Teer Quarry 0 7 7 7 7 7

Purchases 1.4 0 0 0 0 0

Jordan Lake

2 2 2 2 10

Total Available Supply (MGD) 38 46 46 46 46 54

Service Area Demand 25 28 32 36 39 41

Total Demand (MGD) 25 28 32 36 39 41

Demand as Percent of Supply 64% 61% 69% 78% 85% 76%

44

47

45

43

47

49 48

51

45

48

50

243

286

325 338

356 367

377 384

200

250

300

350

400

450

40

42

44

46

48

50

52

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Po

pu

lati

on

Ser

ved

Tho

usa

nd

s

Ave

rage

Dai

ly D

eman

d (

MG

D)

Average Daily Demand

Population Served

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 26

Figure 18: Projected supply and demand for the City of Durham

The City of Raleigh has access to 75 MGD through the E.M. Johnson WTP at Falls Lake (Table 11 and Figure 19). The WTP capacity is rated at 86 MGD, but the plant can only reliably deliver 75 MGD due to hydraulic restrictions and lack of filter redundancy (Hazen and Sawyer 2010). In 2010, the Dempsey E. Benton WTP was opened to provide an additional 20 MGD from Lake Benson and Lake Wheeler at a cost of $97.5M (Morrison, 2011). The WTP at Falls Lake is expanding to handle an additional 34 MGD by 2015 at an estimated cost of $250M (Morrison, 2011; Raleigh, 2007). The final water supply project currently being assessed is the construction of a new reservoir on Little River for an additional 13.7 to 20 MGD for an estimated $263M (Morrison, 2011; Raleigh, 2007). The Little River project is hotly debated due to the large amount of area that would be inundated for such a small increase in water supply. Water demand for the city of Raleigh is projected to more than double by 2050 and the peak demand is anticipated to exceed the projected future water supply by 2040 (Morrison, 2011). Raleigh is currently searching for new water supply sources. Clearly, Falls Lake is an essential water source to protect to ensure the future of Raleigh and the surrounding municipalities receiving water from Raleigh (Figure 20).

Table 11: Projected supply and demand for the City of Raleigh

City of Raleigh 2007 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

Falls Lake Reservoir 75 75 120 120 120 120

Smith Creek Reservoir 2 2 2 2 2 2

Dempsey Benton WTP 0 20 20 20 20 20

Little River Reservoir

0 17 17 17 17

Total Available Supply (MGD) 77 97 159 159 159 159

Service Area Demand 52 50 76 92 102 117

Sales 0.6 2 2 2 2 2

Total Demand (MGD) 52 52 78 94 104 119

Demand as Percent of Supply 68% 60% 49% 59% 65% 75%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2007 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

MG

D

Total Available Supply (MGD)

Total Demand (MGD)

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 27

Figure 19: Projected supply and demand for the City of Raleigh

Figure 20: Municipalities serviced by the Raleigh Water Utility

For more information on projected water demand:

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

2007 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

MG

D

Total Available Supply (MGD)

Total Demand (MGD)

Upper Neuse River Basin Watershed Protection Revenueshed Analysis

Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina | 28

Neuse River Basin Water Resources Plan (2010). N.C. Division of Water Resources. URL: http://www.ncwater.org/Reports_and_Publications/Basin_Plans/Neuse_RB_WR_Plan_20100720.pdf

3.2 Point Source (Municipal Wastewater Discharge in the UNRB)