Ultrapar Participacoes SA

Transcript of Ultrapar Participacoes SA

DISCLOSURE APPENDIX AT THE BACK OF THIS REPORT CONTAINS IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES, ANALYST CERTIFICATIONS, AND THE STATUS OF NON-US ANALYSTS. US Disclosure: Credit Suisse does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the Firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision.

22 June 2016 Americas/Brazil

Equity Research Oil & Gas Refining & Marketing

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) Rating OUTPERFORM Price (22-Jun-16,R$) 71.01 Target price (R$) 89.00 52-week price range 73.71 - 54.35 Market cap (R$ m) 39,510.33 Enterprise value (R$ m) 45,940.02 *Stock ratings are relative to the coverage universe in each

analyst's or each team's respective sector.

¹Target price is for 12 months.

Research Analysts

Andre Natal

55 11 3701 6299

Regis Cardoso

55 11 3701 6297

INITIATION

There Is Still Music in Them

■ Initiation: We are initiating coverage of Ultrapar with an Outperform rating

and a BRL89.00/share target price. Ultrapar is widely believed to be a good

but expensive company. We don't think it is expensive at all. There are still

many opportunities to add value. Rather than focusing solely on what is in

our numbers, we highlight what is not. Our target doesn't include Ipiranga's

expansion above cost of capital, the acquisition of Alesat, the increase in

convenience stores coverage, a possible acquisition of Liquigas, the ramp up

of Extrafarma, and so on, and yet we still see 25% upside potential. Investors

buying Ultrapar may get more, if a fraction of these opportunities materialize.

■ One Big Question. The company's track record is impressive. The question

then becomes, Can this music go on? To answer it, we went through the

fundamentals behind it, and we think they are not only still there but getting

stronger each day, in spite of the recent challenging macro environment.

■ Seven Answers To Be a Buyer: We unfold our main thesis into seven

essential questions that have not yet been fully addressed: (1) Why is the

distribution business so good in Brazil? (2) What are the prospects for

volume growth? (3) How do margins expand and what should we expect? (4)

How promising is the CONEN (Mid-West, North, Northeast) area? (5) How

much should we expect from fuel imports? (6) What are the prospects for the

other businesses? (7) But isn't it too expensive already? After going through

them, we believe the company owns businesses enjoying strong entry

barriers, in a market that will grow for many years, especially in CONEN,

allowing scale and margin expansion. Imports may also contribute in the

short term. We think Ultrapar can add shareholder value for years to come.

■ Valuation: We used five different valuation methods, and most point to

significant upsides. Our target is DCF based, assuming future returns will

decline. Our Bull case (BRL125/sh) includes the additional opportunities we

mapped. Our Bear case (BRL69/sh) assumes returns will decline faster.

Share price performance

On 22-Jun-2016 the SAO PAULO SE BOVESPA INDEX

closed at 50735.02804

Daily Jun23, 2015 - Jun22, 2016, 06/23/15 = R$67.55

Quarterly EPS Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 2015A 0.69 0.59 0.53 0.89 2016E 0.69 0.62 0.63 0.80 2017E 0.59 0.73 0.70 0.91

Financial and valuation metrics

Year 12/14A 12/15A 12/16E 12/17E Revenue (R$ m) 67,736.3 75,655.3 79,816.7 89,223.4 EBITDA (R$ m) 3,174.4 3,964.2 4,133.9 4,606.9 EBIT (R$ m) 2,286.6 2,961.5 3,050.7 3,454.1 Net Income (R$ m) 1,241.6 1,503.5 1,446.9 1,612.2 EPS (CS adj.) (R$) 2.23 2.70 2.60 2.90 Prev. EPS (R$) - - - - Dividend yield (%) 2.0 2.2 2.1 2.4 P/E (x) 31.8 26.3 27.3 24.5 EV/EBITDA 13.7 11.3 11.1 10.0 P/B (x) 5.13 4.97 4.64 4.24 ROE stated-return on equity 17.5 19.2 17.6 18.1 ROIC (%) 13.25 14.91 13.84 14.26 Net debt (R$ m) 4,106 5,395 6,430 6,622 Net debt/EBITDA (12/15E, %) 53.1 67.7 75.1 70.7 Capex (R$ m) -1,216 -1,334 -1,792 -1,518

Source: Company data, Thomson Reuters, Credit Suisse estimates

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 2

Table of Contents

Introduction 4

Investment Summary ............................................................................................... 6

Ultrapar 10

Is It Too Good to Be True? ..................................................................................... 10

Ipiranga 13

Question #1: Why Is This Business So Good In Brazil? ........................................ 13

Question #2: What Are the Prospects for Volume Growth in Brazil? ..................... 21

Question #3: How Do Margins Expand and What Should We Expect? ................. 41

Question #4: How Promising Is the CONEN Area? ............................................... 48

Question #5: How Much Should We Expect From Fuel Imports? .......................... 56

Other Businesses 69

Question #6: What Are the Prospects for the Other Businesses? ......................... 69

Valuation 83

Question #7: But Isn't It Too Expensive Already? .................................................. 83

Risks 102

How Can We Be Wrong? ..................................................................................... 102

Appendix 105

Appendix 1: Ultrapar Through HOLT® Lens ......................................................... 105

Appendix 2: The HOLT® Framework .................................................................... 107

Appendix 3: Management Profile and Holdings ................................................... 112

Appendix 4: Ultrapar Financials ........................................................................... 116

Appendix 5: Financials Summary ......................................................................... 117

We would like to thank Gabriel Cordaro for his valuable contribution to the creation

of this report.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 3

Introduction "Opportunity meeting the prepared mind—that's the game" (Charlie Munger)

In 1915, the Russian painter, Kazimir Malevich painted a Black Square on a white canvas.

As simple as that. Some say he depicted the end of painting, a denial of art. Supposedly,

everything had already been painted, and therefore painting was over. But it so happens, it

was not. A lot has been done since then, and art never came to an end. It never will.

We think Ultrapar is like painting. We still see it fresh, with lots of possibilities. Many think

its value is already fully unlocked, completely known, entirely priced in, and that there is

nothing new to come. Some also think it's been covered by so many and for such a long

time, that there is nothing left to be said about it, as a Black Square on a white canvas.

We disagree. In this report we ask the question: Can the music go on? To answer that

question we derived seven smaller questions from it that we think lie in the inner core of

the investment case. By answering them, we intended to make clear what are the

fundamental principles that have guided the company's track record of value creation and

why we believe they are still in place, making this trend likely to continue for many years to

come. We tried to map not only what the company is doing, but also what the company is

not doing yet. And our view is that numerous opportunities to create value lie ahead.

We once heard that, "Musicians don't retire. They stop when there's no more music in

them." We think there is still music in Ultrapar. And our numbers suggest that the music is

playing loud, but that the market is not listening to it.

How to read this report?

This report will look too long for some investors. Hopefully, a few will read it thoroughly

and (who knows?) still wish for more. But some might think it deserves the words of

Winston Churchill, who once said: "This paper by its very length defends itself from the risk

of being read." The more we try to find the right balance between a concise view and an

adequate level of detailed analysis, the more we see there is no perfect formula with which

everybody would agree. The way to overcome that is to present our analysis in blocks that

can be entirely skipped. So, investors can jump directly to the topics they are most

interested in. And, to those who seek only a brief summary of our views, the three-page

investment summary may suffice. We think this way of organizing the ideas prevents us

from taking too much of the time of those who don't have any, but also from being too

shallow on relevant matters.

We think these seven fundamental questions were not yet answered but are essential for

an adequate understanding of the company's main value drivers, and the opportunities

that lie ahead. Questions are always a good way to address a complex issue. We tend to

agree with the professor and neurobiologist Stuart Firestein: "Questions are more relevant

than answers. Questions are bigger than answers. One good question can give rise to

several layers of questions, can inspire decades-long searches for solutions, can generate

whole new fields of inquiry, and can prompt changes in entrenched thinking. Answers, on

the other hand, often end the process". We hope our seven questions adequately address

investors' curiosity and interest.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 4

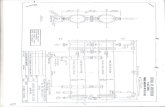

Figure 1: Our Fundamental Questions (An Illustrated Summary)

Source: Credit Suisse analysis

#1 - Economies of Scale # 2 - Logistics Infrastructure #3 - Network of Branded Stations #4 - Pricing Power

#5 - Access to Fuel Supplies #6 - Single Supplier #7 - Value of a Brand #8 - Playing Defensive and Offensive

Ultragaz Oxiteno Ultracargo Extrafarma

Fundamental Question: Can The Music Go On?

Q2) What Are The Prospects For Volumes Growth In Brazil? Q3) How do Margins Expand and What Should We Expect?

Q1) Why Is This Business So Good In Brazil?

Q4) How Promising Is The CONEN Area? Q5) How Much Should We Expect From Fuels Imports?

Q6) What Are The Prospects For The Other Businesses?

Q7) But Isn't It Too Expensive Already? Risks: How Can We Be Wrong?

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Income SSE 2014

Income CONEN 2014

Income CONEN 2004

1 mw

1 mw1/2 mw

2 mw

2 mw

3 mw

3

1/4 mw1/2 mw

5

1 minimum wage

2 mw

3 mw

5

1/2 mw

5

% of Population below each salary level

Ranges

of

sala

ry (

BR

L/

month

)

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2.0

2.2

2.4

Q1 10 Q4 10 Q2 11 2011 Q3 12 Q1 13 Q4 13 Q2 14 2014 Q3 15

Economies of scale Inflation

Compound Inventory gains

Actual EBITDA margin

Model EBITDA margin

5,415 5,499 5,662 6,086 6,460 6,725 7,056

15% 15% 15%16%

16%17%

18%

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Ipiranga's # of stationsIpiranga's share of stations

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

Q1 10 2010 Q4 11Q3 12Q2 13Q1 14 2014 Q4 15

Average

Price exposure:

EBITDA margin

Branded

15

25

35

45

55

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Unbranded

1

1.05

1.1

1.15

1.2

1.25

1.3

1.35

Q1 10 2010 Q4 11Q3 12Q2 13Q1 14 2014 Q4 15

Volume sold

Economies of scale:

33% 35% 35% 35% 34% 33% 33% 32%

24% 21% 21% 21% 22% 22% 21% 22%

4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4%

22% 24% 24% 23% 23% 23% 23% 23%

16% 16% 17% 17% 18% 18% 19% 19%

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015BR Ipiranga Ale White flag Raízen

3.7%3.0%

0.0%

-5.0%-4.1%

5.7%

2.0% 1.7%

-1.8%

2.3%

-0.9%

-2.6%

-3.1%

-8.4% -8.3%

3.0%

1.3%

0.1%

-2.7%

-1.5%

1Q 15 2Q 15 3Q 15 4Q 15 1Q 16

Ipiranga

Raizen

BR

Market

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000Jan-0

2

Dec-

02

Nov-

03

Oct

-04

Sep-0

5

Aug-0

6

Jul-

07

Jun-0

8

May-

09

Apr-

10

Mar-

11

Feb-1

2

Jan-1

3

Dec-

13

Nov-

14

Oct

-15

International Gasoline International Diesel

Domestic Diesel Domestic Gasoline

Oxiteno19%

Ultragaz8%

Ultracargo

3%1%

Extrafarma

74.5

9.1 4.1 1.6 3.3 12.51.4

11.1

92.6

Ipiranga Oxiteno Ultragaz Utracargo Extrafarma Corporate Net debt 12mo carryfwd

Ultrapar

-

2

4

6

8

10

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Ipiranga's share of imports Other players' share of importsVolume (kbd)

Marg

in (

$/b

bl)

$ 303 mn$34mn $ 125 mn$14mn

Diesel Gasoline

-

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

19

96

19

98

20

00

20

02

20

04

20

06

20

08

20

10

20

12

20

14

20

16E

20

18E

20

20E

20

22E

20

24E

20

26E

20

28E

20

30E

20

32E

20

34E

20

36E

20

38E

20

40E

20

42E

20

44E

20

46E

20

48E

20

50E

Ave

rage

Sal

es p

er S

tati

on

(m

3/y

)

CS Forecast

USA Actuals

Ipiranga Actuals

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 5

Ultrapar: There Is Still Music in Them

Investment Summary

■ Conservative Approach. We are initiating coverage of Ultrapar with an Outperform

rating and a 12-month forward target price of BRL 89.00/share. The company is widely

believed to be good quality, but it is also believed to be expensive and that current

prices would only be justifiable under aggressive assumptions for future growth and

margin behavior. However, we couldn't disagree more. We believe just the opposite is

true. To justify current prices, one would have to assume that capital will be allocated

at returns much lower than current levels for all the businesses Ultrapar owns. That's

exactly what we did in our base case. We conservatively assumed returns will be lower

and we still see a c.25% upside potential for the shares. But we also mapped a number

of additional opportunities that can lead to much higher upsides if at least part of them

is implemented. We think value creation is all about opportunity meeting a prepared

mind. That's why we say: There's still music in them.

■ Can the Music Go On? We chose to approach this question dividing it into seven

smaller questions that lie in the inner core of its businesses' fundamentals. (1) Why is

the distribution business so good in Brazil? (2) What are the prospects for volume

growth in Brazil? (3) How do margins expand and what should we expect? (4) How

promising is the CONEN area? (5) How much should we expect from fuel imports? (6)

What are the prospects for the other businesses? (7) But isn't it too expensive already?

We wouldn't be buyers if we just thought it's a good-quality company, because no good

business justifies whatever entry price. We wouldn't be sellers just because a good

track record can't go on forever. So, we thought it was essential to go through these

seven questions in order to understand the main value drivers behind the company's

outstanding track record of above average returns. After doing it, our conclusion was

that the fundamentals leading to such performance will not only remain in place, but

might get stronger for many years to come.

■ Lollapalooza Effects. When we see above-average returns on capital, we think

"moats" (or sustainable business protections) must be in place. Ultrapar is no different.

And particularly its main business—distribution—has strong moats, that, in our view,

become each day harder to cross. To put it simply, Ipiranga has a market position in

which: (1) there are enormous economies of scale; (2) logistics infrastructure acts as

an entry barrier; (3) more than 7,000 resellers are contracted; (4) pricing power is such

that the company can gradually and monotonically adjust margins; (5) access to fuel

supplies depends on previous volumes making it almost impossible for newcomers; (6)

the presence of a single refiner creates stability on the supply side; (7) brand power is

continually increasing and turning into better margins; and (8) the company can play

defensively and offensively by buying smaller distributors, which was the case with the

AleSat acquisition. In our view, these factors reinforce and combine with each other,

leading to hard-to-measure "lollapalooza effects" (non linear synergies).

■ "Opportunity Meeting the Prepared Mind—That's the Game." Rather than saying

only what is included in our numbers, we would also like to highlight what is not. We

think there are plenty of opportunities yet to be explored by the company to keep

creating shareholder value. These opportunities range from: deploying capital at least

in line with current return levels for longer (+BRL23.5/share); concluding the deal to

purchase Alesat (+BRL6.2/share); increasing coverage of convenience stores in its

service stations (+BRL6.4/share); possibly acquiring Liquigas (+BRL1.6/share);

ramping up Extrafarma to the initial plan of 100 stores/year, rather than 60 stores/year

(+BRL1.5/sh); exploring synergies among its different businesses; expanding the

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 6

lubricants business; and so on. None of them were included in our base case and

target price. So, we believe that investors buying Ultrapar are buying 25% upside if the

future is just mediocre relative to current performance, and potentially a much higher

upside if at least a fraction of these additional options gets implemented.

Valuation and Sensitivities

■ Different Methodologies. We used five different valuation methodologies to assess

Ultrapar, and most of them point to a considerable upside to current share prices. Our

target price is based on a DCF model, in which we assume the returns on new

invested capital will decrease relative to today's figures. For the main business,

Ipiranga, that means return on invested capital will converge to 13% from current 25%.

The following table in Figure 2 summarizes the results of the different approaches we

used to define our base case. Figure 3 shows the DCF based valuation's sensitivity to

cost of capital. Figure 4 shows the main assumptions behind our base case. The main

point we would like to highlight is that we sought to apply conservative assumptions in

all of the methods, and none of the yet-to-explore opportunities were included in our

numbers. In the section about valuation (Question #7) we discuss the opportunities we

think lie ahead and might be explored by Ultrapar, creating additional upsides to our

numbers. Figure 5 shows a summary of the potential upsides leading to our bull case.

We also present a bear case, that assumes returns will converge to cost of capital

even faster.

Figure 2: Valuation Summary Table in BRL/share

Source: Credit Suisse estimates

Type Valuation MethodValue/share

in Mar-2017Description Preference

Level of

DetailTime Scale

Group two-parts DCF BRL 89/sh

Discounted Cash-flow approach with explicit model to 2020 and two periods of

continuing value '2020-2030' and '2030 onwards' with declining RONIC and

reinvestment assumptions

1st

SOTP BRL 93/sh

Business-by-business discounted cash-flow approach with explicit model to 2020

and two periods of continuing value '2020-2030' and '2030 onwards' with

declining RONIC and reinvestment assumptions

2nd

SOTP EV/EBITDA BRL 79/sh Implied EV/EBITDA multiples applied to each business's EBITDA '16 3rd

Group EV/EBITDA BRL 81/sh Historical EV/EBITDA multiple applied to group's consolidated EBITDA '16 4th

Group P/E BRL 66/sh Historical P/E multiple applied to group's consolidated earnings '16 4th

Multiples

DCF

Higher

Lower

Perpetuity

2016

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 7

Figure 3: Target Price Sensitivity Analysis in BRL per share

Figure 4: Base Case Main Assumptions

Source: Credit Suisse estimates Source: Credit Suisse estimates

■ Assessing risk-rewards. In order to assess the balance between downside risks and

potential upside rewards, we have analyzed the Bear and Bull scenarios shown in

Figure 5. Bull scenario incorporates a non-exhaustive list of potential upsides which we

have valued (and discussed in greater detail in Figure 156). The Bear scenario

assumes that from 2020 onwards Ultrapar will never find new opportunities to deploy

capital in a value-accretive way. This could come as a result of fiercer competition,

exhaustion of good investment opportunities in the fuel distribution market, changes in

consumption habits, or other types of macro headwinds in the long-term. The Bull

scenario points to significant upside, c.81%, whereas Bear scenario points to only a

small downside, c.-3%. We think this is a compelling risk-reward profile.

Figure 5: Bear, Base, Bull Cases

Source: Credit Suisse estimates

Risks To Our Call

■ What If #1: Consumer Preferences and Solutions for Mobility. We might be wrong

in a number of ways. First, because we are dealing with businesses whose value

materializes over the long run, this assumes we are able to accurately understand how

consumer preferences will evolve in the decades to come. If new solutions for mobility,

to name one, are developed, or if people's habits require less and less mobility due to

increasingly virtual social interactions, demand for fuels might not continue to grow and

we might be proven wrong. We don't expect these things to happen during a time

frame that could materially affect Ultrapar's value, but we can of course be wrong.

■ What If #2: Macro Conditions. If macro conditions get worse and the current

economic recession proves to be long lasting, if inflation accelerates, if country risks

increase materially, or any other macro event takes place, our beliefs might have to be

reviewed.

R$ 89/sh 10% 12% 13.9% 14% 16% 18%

11% 853 361 232 228 166 130

12% 315 208 157 155 123 102

13% 192 146 118 117 98 84

14.3% 127 105 89 89 77 68

15% 106 90 78 78 68 61

16% 87 75 67 66 59 54

17% 73 65 58 58 52 48

Co

st

of

Eq

uit

y

Cost of Debt Assumption 2016E 2017E 2018E 2019E 2020E

GDP (YoY%) -3.5% 0.5% 2.0% 2.0% 2.0%

FX (avg) 3.60 3.76 3.92 4.10 4.28

Brazilian inflation (IPCA) (%) 7.5% 6.5% 6.5% 6.5% 6.5%

Selic (%) 14.25% 14.00% 13.75% 13.50% 13.25%

Ke (R$, nominal) (%) 15.6% 14.5% 14.4% 14.3% 14.3%

Cost of Debt (%) 15.0% 14.7% 14.4% 14.2% 13.9%

Wacc (R$, nominal) (%) 13.4% 12.6% 12.5% 12.5% 12.5%

Diesel demand growth (YoY%) -4.1% 0.5% 2.0% 2.0% 2.0%

Otto demand growth (YoY%) -3.0% 0.5% 2.0% 2.0% 2.0%

Valuation MethodValue/share

in Mar-2017

Upside

relative to BRL73.4/shDescription

Blue-sky scenario BRL 128/sh 81%

Same as base case plus upsides from i) higher RONIC at Ipiranga, ii) Alesat deal, iii)

Convenience stores expansion, iv) Possible M&A in LPG business and v) More

aggressive expansion in Extrafarma

Base case BRL 89/sh 25%Two parts DCF assuming return on new investments in 'the next decade', 2020-2030,

will average 18% in nominal terms.

Bear scenario BRL 69/sh -3%Assumes growth from 2020 onwards will not add value, but rather be made through

investments that return cost of capital.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 8

■ What If #3: Refineries Ownership. If Petrobras decides to sell a significant portion of

its refining business to private companies, it could lead to an increase in the need for

capital deployment on the part of distributors, as a more competitive refining segment

will likely be less prone to invest in logistics capacity in the country. Fluctuations in

refinery-gate prices would also very likely increase, meaning more volatility in

distribution margins. We are not assuming this as our base case scenario, but we

might be wrong.

■ What If #4: Consolidation May Change Competitive Landscape. We think

consolidation remains a trend in the fuel distribution and in the LPG distribution

businesses. The AleSat deal not being approved for any reason would be a risk to our

call. We also see a risk stemming from the potential sale of Petrobras's fuel distribution

arm, BR Distribuidora. Depending on the format the potential deal may take and on

who the buyers would be, it could materially change the competitive landscape and we

would have to reassess our call. Another similar risk relates to the sale of Liquigas,

Petrobras's LPG distribution subsidiary. Any risk this sort could result in higher

competitive pressure on Ultrapar from the company's peers, reducing the possibilities

for market share gains and economies of scale.

■ What If #5: Competition Gets More Aggressive. Finally, we consider price wars are

not in the best interest of any of the existing big distribution companies, but we might

be proven wrong if we see a self-destructive behavior like that, with companies willing

to sacrifice their margins for an additional market share percentage point.

■ What If #6: Ultrapar's Management, Governance and Capital Deployment. We

view Ultrapar as a good reference in terms of capital allocation capabilities, as was

once again evidenced by the AleSat deal. But we cannot rule out the risk of future

generations of management not being able to deploy capital as well. As we will see

ahead, fair value is extremely dependent on returns on new invested capital. We would

have to change our minds if this or any governance issues arise.

■ What If Other What Ifs Arise? The future reserves many unknowns. We are never

ready for them.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 9

Ultrapar

Is It Too Good to Be True?

"Mastery is a mindset." (Daniel Pink)

■ Some Say: The Music Can't Go On. Most of the arguments we see in the market

against Ultrapar's ability to keep going well seem to rely on an assumption that this is

just too good to be true. Ultrapar's amazing track record of margin expansion, along

with the continuous share price appreciation, makes investors cautious about paying

too much to own the business. We think this alertness is good, as no business justifies

whatever entry price. As Warren Buffett said: "What is smart at one price is dumb at

another." But, on the other hand, we don't typically like the arguments that come simply

on the back of an alleged "too good to be true" thesis. We think good businesses run

by good management can continue delivering good returns for longer than market

participants are willing to accept. We prefer the arguments that explore the true value

drivers of the businesses in order to understand if a sustainable competitive advantage

is in place. And we think this is the case here.

■ Some Say: It's Expensive but Has Good Quality. Most of the arguments we see in

the market in favor of investing in Ultrapar go like this: "We think it's expensive, but it is

a good-quality company with good management, and therefore it must be a good

investment." First of all, we don't agree that good-quality companies are necessarily

good investments, for obvious reasons. But we also don't agree that it is expensive in

the first place. We like the investment for a different reason: We believe the potential

value is bigger than prices, and this is what investing is all about. We never like

anything because it looks to have good quality, others like it, or news flow is favorable.

We like it when we think prices are lower than value, the latter measured

conservatively.

■ No Sacred Businesses, No Single Shots. Throughout the years, Ultrapar has kept

expanding its portfolio of businesses both organically and through acquisitions. The

company pretty much knows its circle of competence and keeps adding value to it. As

Thomas Watson once said: "I'm no genius. I'm smart in spots and I stay around those

spots." The gradual addition of businesses in a disciplined way is something we tend to

see as positive. It makes the company more able to deploy the cash from its operations

wherever most appropriate at each particular moment. We are not of the opinion that

diversification is always good or necessary. But we think value creation opportunities

sometimes become scarce within a specific business, and we like management teams

that are ready to play other games. Figure 6 shows the history and breakdown of the

group's EBITDA generation. It shows how the consolidated earnings power increased

in spite of the business cycles and specific challenges of each individual business

segment. Figure 7 shows the group's performance from a cash flow perspective,

comparing all the cash generated to the cash reinvested in the portfolio of businesses

since 2007.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 10

Figure 6: Ultrapar Historical EBITDA Composition

per Business in BRL millions

Figure 7: Free Cash Flow Growth vs. Invested

Capital Throughout the Years in BRL millions

Source: Company data, Credit Suisse analysis Source: Company data, Credit Suisse analysis

■ Metamorphosis. At the beginning, Ultrapar was pretty much an LPG distributor,

period. But the flexibility in capital allocation allowed the company to keep adding

businesses and also expand organically on different fronts, benefiting from the different

business cycles. Figure 8 depicts the EBITDA composition in relative terms among the

businesses. Figure 9 shows the capex profile throughout the years. Both charts clearly

show that Ultrapar is in constant metamorphosis. This culture is something we believe

builds up on itself and gives us confidence to believe in above-average capital

allocation. This is an important issue in valuing Ultrapar, as we will later discuss. It

always depends on the sustainability of its competitive advantages so that future

capital can keep being deployed at above its cost in the long run. The company is now

on the verge of consummating one more of these above-average capital allocation

initiatives, through the acquisition of AleSat, the fourth biggest fuel distributor in Brazil.

If that acquisition is approved, we think it will be yet another example of a trend that

has been in place for many years and that will likely be there for longer.

Figure 8: Historical % Contributions of Each

Business to the Group's EBITDA in %

Figure 9: Historical Capex Allocation Among the

Businesses within the Group in %

Source: Company data, Credit Suisse analysis Source: Company data, Credit Suisse estimates Note: Does not include capex in acquisitions

0 323 593 830

1,0

73

1,3

30

1,6

53

2,0

30

2,2

88

2,7

69

281

252

211

281

307

282

246

281

306

357

192

156

210

171

241

261

352

441

404

740

38

4351

104

111

118

143

158

167

26

30

29

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Extrafarma

Ultracargo

Oxiteno

Ultragaz

Ipiranga

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Cumulative New Invested Capital Cumulative Cash from Operations

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Oxiteno

Ultragaz

Ipiranga

Ultracargo

Extrafarma

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Oxiteno

UltragazIpiranga

Ultracargo

Extrafarma

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 11

■ Good Managements Add Value. We completely agree with Seth Klarman that "Good

managements add value. Good managements have lots of levers they can pull, they

can buy-back stocks when they are undervalued, they can use stocks as currency

when they are overvalued. Bad managements will only think about themselves first."

Ultrapar is a strong evidence of this, as it was able to keep adding value throughout the

years. In the long run, we believe skill overcomes luck, and discipline beats market

conditions. We have already seen good assets destroy value under managements not

focused on shareholder's returns. We have seen good managements add value out of

not-so-good assets and under tough business environments. But we think Ultrapar has

the best of both: good businesses and a management team with the appropriate

mindset. And as the psychologist and professor Daniel Pink puts it, "mastery is a

mindset."

■ Entry Points. Many investors wait for a significant price drop in Ultrapar's shares that

could offer them a good entry point. This happened in really very few instances in the

past five years. As we will hopefully make clear in the following pages, the company

owns well-positioned businesses that enjoy economies of scale and have a very

significant margin protection. In terms of volumes, despite the recent economic

downturn, long-term prospects remain good. So, waiting for prices to fall might be

frustrating, as the company has been able to consistently increase EBITDA every

single quarter, now for 39 consecutive quarters. Just to highlight this achievement, it

means 10 years with no instance of a quarterly EBITDA lower than in the year before.

We think every time the company's share prices reflect a convergence of future

margins to a flat level, as if the company's music were fading, the market is getting it

wrong. And the search for entry points becomes a pointless and long wait. The real

question becomes whether or not current prices already reflect Ultrapar's competitive

advantages, and our answer is no. In Question #7, we discuss the company's valuation

under different methodologies. They point toward higher equity value than current

prices indicate.

■ Monotonic Growth Sounds Boring. We think dancing to the music is much more fun

than dancing to the noise, but it seems this music is too long and monotonic for the

market to appreciate. People sometimes wait for earnings momentum, value triggers,

and positive news flow to indicate the right time to buy and enjoy a rally. But we believe

Ultrapar is a business to own. Its beauty is not in rallies, it's in the power of

compounding returns over the long run. The recent economic downturn has caused

worries about the company's ability to keep adding value. So, some have considered

selling it to avoid a decline. But, as Peter Lynch says: "It would be wonderful if we

could avoid the setbacks with timely exits, but nobody has figured out how to predict

them. Moreover, if you exit stocks and avoid a decline, how can you be certain you'll

get back for the next rally?" The company keeps gradually beating market consensus

estimates every quarter and also, time after time, surprising the market with timely

acquisitions of businesses with a good fit and also at good prices.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 12

Ipiranga

Question #1: Why Is This Business So Good In

Brazil?

"Frequently, you’ll look at a business having fabulous results. And the question is, ‘How long can this continue?’ Well, there’s only one way I know to answer that. And that’s to think about why the results are occurring now—and then to figure out what could cause those results to stop occurring." (Charlie Munger)

■ Are There Moats in This Business? In trying to assess the reasons a particular

business has been delivering good results for a long time, we like Charlie Munger's

approach of trying to find moats, or business barriers, that allow for sustained

performance. In capitalism, every time a company or sector is enjoying good margins

and returns, other players will try to join the party and, when it gets too crowded, all the

fun will be almost completely gone. So it is essential to understand how those margins

could be threatened. After analyzing the distribution business in Brazil, we concluded

that there are numerous and enormous barriers in place and that these barriers

reinforce and combine with each other. We not only think there are barriers in place,

but also that they are getting bigger.

■ The Party Is Not Open for Newcomers. Any company willing to assume a significant

portion of the distribution business within a certain geography will typically do that

through acquisitions. It makes no sense for a newcomer to build logistics infrastructure

from scratch next to an existing distribution network. This means a very high entry cost,

besides the marketing costs involved in building a brand. Figure 10 shows how this

segment has been gradually consolidating itself, concentrating in a few big companies.

These big four include AleSat, which is about to be purchased for BRL 2.168bn by

Ipiranga, if the anti-trust authority approves the deal announced on June, 12, 2016.

This is a business in which scale matters, as we will see ahead. And once a logistics

network is in place, it always makes much more sense for an established distribution

company to expand itself and supply the marginal demand than for another company

to build a new distribution base around the corner. This will always be the case, in our

view, and is a sustainable competitive advantage for those who are already well

positioned in the sector.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 13

Figure 10: History of Sector Consolidation Since 1990

Source: Sindicom, Credit Suisse Research Note: The potential purchase of AleSat by Ipiranga will leave the sector with now only three big distribution companies, which compares to eight companies in the 1990's. This is a material consolidation that allowed significant scale gains.

■ Moat #1: Economies of Scale. As we mentioned, the marginal investment to allow for

growth is always lower for the already established distribution company than it would

be for a newcomer. Building an additional tank in an existing facility is cheaper than

building an entire distribution facility. Also, using an existing tank with a higher turnover

is cheaper than building a new tank. On the operational side, fixed costs also allow for

economies of scale when volumes increase. So, this is a business in which scale

matters. There are many sectors in which size is a problem. As Warren Buffett says:

"Size is the enemy of performance to a significant degree." But we think the distribution

business enjoys the benefit of scalability, and it is not by chance that the survivors in

this sector in Brazil have made every effort to become bigger while keeping their

expansion strategies. In Question #3, we present a more detailed discussion of

economies of scale and how they have helped to boost margins.

■ Moat #2: Logistics Infrastructure. In order to play a major role in the distribution

business, a wide spectrum of well positioned assets is necessary. This includes a

combination of access to fuels, storage capacity, and the right distribution capability.

Throughout the years, after the already-mentioned consolidation process in the sector,

the few really big distribution companies accumulated assets with enough scale and

coverage that provide them with a sustainable competitive advantage. Having an

established country-wide network of distribution bases constitutes a big enough barrier

to discourage newcomers. Ipiranga is well positioned relative to the main sources of

fuels (mainly Petrobras's refineries) and has an established portfolio of assets,

including large-scale blending and storage capacity, truck-loading facilities, and a

transportation subsidiary with its own trucks fleet. Figure 11 shows Ipiranga's portfolio

of distribution bases that spread through all the high consuming regions over the whole

1993

2002

2006

2007

1990 Today

2003

2008

2001 2004 2009

1999

2009

2011

2008

Only the Service Stations was transferred or partially transferred

Distribution Companies members of Sindicom

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 14

national territory and those of other players. The potential purchase of AleSat will add

to Ipiranga's current network ten additional distribution bases spread all over the

country. Ipiranga might be able to use its existing infrastructure to distribute part of the

volume after the deal goes through, if it does, meaning there might be future

economies of scale in the operation of distribution bases after AleSat joins Ipiranga's

network.

Figure 11: Network of Distribution Facilities Per Company in Brazil

Source: ANP, Credit Suisse Research Note: The size of the bases displayed in orange represents the sum of the smaller capacities of other players.

■ Moat #3: Network of Branded Stations. In Brazil, law does not allow distribution

companies to operate service stations. They may or not be owned by a distributor but,

in any case, another company must be in charge of their operations, typically small

independent private companies. The big distribution companies compete among

themselves to brand stations, through tailor-made contracts that involve the

deployment of capital from the distributor and the exclusive right to supply fuels. As

branded stations can only buy products from the same distribution company, this

network of branded stations constitutes an additional entry barrier for a newcomer

willing to play the distribution game. Terminating the existing contracts or establishing

new ones to build a significant client base would require a huge amount of capital.

Others

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 15

Ipiranga currently has contracts with a network of 7,241 stations, or c.18% of all the

stations in Brazil. If the purchase of AleSat is approved, Ipiranga will expand its moat,

becoming the distributor with the greatest number of stations in the country, exceeding

BR, jumping to c.23% of the total. Figure 12 shows the historical evolution of Ipiranga's

network both by number of stations and share of the total. Figure 13 shows the

historical levels of total capital deployed by Ipiranga and its relation to the size of the

stations network throughout the years.

Figure 12: History of Ipiranga Service Stations and

Ipiranga's Share of Total Stations in Brazil Ipiranga stations in units, share of total stations in % of stations

Figure 13: Evolution of Ipiranga's Capex per Service

Station Added in BRL millions, Unitary capex in BRL thousand per station

Source: Sindicom, Credit Suisse analysis Source: Company data, Sindicom, Credit Suisse analysis

■ Moat #4: Pricing Power. When the owners of service stations decide to enter into

branding contracts with a big distributor, the retailers benefit from the franchise they

are adopting. So, not only does the station display the image code of the distribution

company but also inherit the customer service standards that typically allow them to

increase volumes relative to previous levels. The other side of this story is that these

contracts establish volume targets that retailers have to achieve but do not pre-

establish price formation. Therefore, through these exclusive contracts, Ipiranga gains

a pricing power that constitutes an invaluable asset. In Question #3, we present a

discussion of the effects of this pricing power that allows Ipiranga to keep gradually

expanding margins. Because of high inflationary pressures, any retail-related business

in Brazil should be particularly concerned about pricing mechanisms that allow them to

preserve margins. There are few businesses in which this sort of pricing power is

present, but we believe Ipiranga increases its power each day to become a

monotonically growing cash generator.

■ Moat #5: Access to Fuel Supplies. The barriers for anybody willing to enter the

distribution business are not limited to the exclusivity contracts with the client base but

also include the access to the very products they are supposed to distribute. Petrobras

requires that the distributors' orders be limited within a narrow range set according to

the historical volumes sold by that distributor. Therefore, even if we could conceive of a

player that would decide to invest big capital to create comparable infrastructure and

would also be willing to pay big capital to terminate current contracts with retailers, this

company would still not be able to purchase significant volumes from Petrobras out of

5,415 5,499 5,662 6,086

6,460 6,725

7,056

15%15%

15%

16%

16%

17%

18%

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Ipiranga's # of stations Ipiranga's share of stations

229 222

383

591

942

746

815

42 40

68

97

146

111 115

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Capex (BRLm) Capex/station (BRL'000/station)

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 16

a sudden. The more scale current players gain, the more they are able to purchase

fuels from refineries and the less other players are able to hurt them in any meaningful

way. Figure 14 shows the level of concentration of Otto and Diesel volumes in the four

biggest companies and how the combined (Ipiranga + AleSat) would look like. Figure

15 shows the companies' market share per product.

Figure 14: Historical Market Share by Company In Diesel + Otto Cycle Fuels in %

Figure 15: 2015 Market Share by Company for Each

Product in %

Source: Sindicom, Credit Suisse analysis Source: Sindicom, Credit Suisse analysis

■ Moat #6: Single Supplier. The fact that almost 100% of refining capacity is

concentrated in a single player significantly differentiates the Brazilian distribution

sector from that of other countries. One such difference is that the existence of a single

state-owned refiner assures no disruption on the supply side, as Petrobras has

historically made all efforts to assure the market is completely served. If we think of a

scenario in which the supply of fuels is locally disrupted, this would likely create much

higher market share fluctuations among distributors, in our view. Another consequence

of a single supplier is that Petrobras has historically delivered a significant portion of its

products at advanced points rather than being limited to the refineries' gates. Although

this movement makes it easier for a smaller distributor to survive, it also reduces

overall cost pressure on the supply side, avoiding margin squeezes and allowing for

lower investments and working capital from distributors. Finally, a single supplier

assures that distribution players have similar supply prices and conditions, leaving

competitive pressures to the stages down the supply chain. Therefore, distributors

have been able to focus their attention on establishing their brands and services over

the years, rather than being pressured from both sides. This factor is very likely to stay

in place as long as Petrobras concentrates most of Brazilian refining operations.

■ Moat #7: The Value of a Brand. We are not in a position to put a number to the

Ipiranga brand, but we don't have to. We again recall the words of Charlie Munger,

when he said: "There are other factors that are terribly important, [yet] there is no

precise numbering you can put to these factors (…) Well practically everybody

overweighs the stuff that can be numbered, because it yields to the statistical factors

they are taught in academia." So, we won't do that. But, we understand that, in a

35% 35% 35% 34% 33% 33% 32%

21% 21% 21% 22% 22% 21% 22%

4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4%

24% 24% 23% 23% 23% 23% 23%

16% 17% 17% 18% 18% 19% 19%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

BR Ipiranga Ale White flag Raízen

20%28%

17%

37%

93%

57%

35%

19%

21%

14%

23%

3%

20%3%

5%

1%

3%3%

20%

20%

4%

19%

4%

32%19%

11%

1%38%27%

63%

18%

1% 0%

22%

HydrousEthanol

Gasoline GNV Diesel Fuel Oil Jet Fuel All Fuels

BR Ipiranga ALE Raízen AirBP Others

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 17

distribution/retail market, brand matters and even more so in a market such as Brazil,

with a history of informality and fuel adulteration. The potential purchase of AleSat, if

approved, will boost Ipiranga's brand exposure to at least 2,000 additional service

stations in the country. In the United States, service stations are also mostly owned by

smaller private companies, rather than by the Oil Majors whose brands they display.

The widely known brands bring the stations a wealth of credibility and help attract

customers. Figure 16 shows the evolution of branded stations in Brazil in comparison

with the so-called white flag (unbranded) stations. Figure 17 compares the level of fuel

sales of branded stations in Brazil to those of unbranded stations. It clearly shows that

brand matters.

Figure 16: Number of Branded and White Flags

Stations in Brazil Throughout the Years in units

Figure 17: Average Fuel Sales Per Service Station of

Branded and White Flags Stations in Brazil in bbpd / station

Source: Sindicom, Credit Suisse analysis Source: Sindicom, Credit Suisse analysis

■ Moat #8: Playing Defensively and Offensively. While running a business in which

there is a moat, the main driver of managers should be to preserve the moat or even

widen it, if possible. Superior returns will attract other players, and moat preservation

should take most of managers' attention and efforts. Accordingly, if competition gets

fiercer despite the entry barriers so as to threaten or weaken the moat, managers can

act defensively by buying the new entrant. By buying smaller distributors that are

consolidating their positions as relevant players, Ipiranga is actually playing both

defensively and offensively, as it is at the same time eliminating the threat of a material

loss of share, and actually increasing its share and moat in the market relative to the

remaining players. We believe, Ultrapar's team, even after the AleSat deal is approved,

if approved at all, will keep looking carefully for smaller distributors to spot other good

opportunities.

■ When Moats Combine: Non-Linear Reinforcements. These barriers combine in a

way that reinforces each other by producing non-linear effects. The bigger a distributor

gets, the more its brand is in evidence and therefore the bigger the benefits for a

retailer to brand his station. This leads to more contracts and, thus, higher market

protection, bigger economies of scale, and higher pricing power. This combination

allows for better margins, which support further expansion. The higher the number of

Ipiranga stations, the more the negotiation power shifts toward the distributor. And the

21,882 22,703 23,524 24,250 25,073 26,109

15,834 15,635 15,709 15,533 14,255 13,884

58%

59%

60%

61%

64%

65%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Branded White Flags % Branded

Branded

Unbranded

15

25

35

45

55

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 18

stronger the franchise, the more final consumers will be attracted to Ipiranga stations.

There are many routes through which we can describe this reinforcement process,

because this is not a linear process. It means that the right combination of these

barriers may lead to hard-to-measure positive results.

■ Will These Moats Increase or Vanish? We think these barriers are increasing. By

observing, in Figure 10, the level of concentration in this sector in the last two decades,

it becomes clear that the power is now in the hands of three or four companies. They

keep branding white-flag stations, gaining scale, expanding margins, and increasing

their presence. And the more all this happens, the more powerful those moats become.

The very nature of the barriers involved is such that they get harder and harder to

overcome.

■ A Big Growing Market. All these entry barriers would be worth little if they existed in a

depressed market. We think, however, that in spite of the current economic downturn,

fuel consumption in Brazil is bound to grow. Fuel demand has been growing c.3.6% for

the last 45 years. We present in Figure 18 Brazil's GDP growth in this period, when

demand for oil products expanded consistently, almost in line with the overall economic

performance. We should highlight that these growth rates were achieved across

economic cycles and under different political regimes, despite global crises and

economic downturns. Figure 19 shows how emerging countries have seen oil demand

expand while developed countries have faced very slow growth or even consumption

declines over the same period. In Question #2, we provide more details on fuel

demand in Brazil and its yet-to-be-developed potential.

Figure 18: Oil Products Consumption Growth vs.

GDP in the last 45 years in Brazil index (1970 = 100)

Figure 19: Oil Consumption Growth in Different

Countries from 1970 to 2014 in kbpd

Source: EPE, BACEN, Credit Suisse analysis Source: Brazil from EPE, Other countries from BP Statistical Review, Credit Suisse analysis.

Note: Other countries' data biofuels, are included

■ How Long Will Consumers Depend on this Business? Oil products are essential

and will very likely be needed for a while, in spite of the threats from new energy

solutions, especially for mobility. Most of the alternatives are still expensive and will be

introduced gradually, with little impact in the near term. We think this might be

particularly true for emerging economies, where there will be a continuous challenge of

-

100

200

300

400

500

600

19

70

19

72

19

74

19

76

19

78

19

80

19

82

19

84

19

86

19

88

19

90

19

92

19

94

19

96

19

98

20

00

20

02

20

04

20

06

20

08

20

10

20

12

20

14

Oil Products GDP Index (1970=100)

GDPCAGR 3.9%

Oil Products DemandCAGR 3.6%

0.6%1.1%

-0.3% -0.4%-0.7% -0.7%

3.6%

5.3%

7.0%

US

Can

ada

Fra

nce

Germ

any

Ital

y

UK

Bra

zil

India

Chin

a

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 19

making energy available at affordable prices to allow for an increase in standard of

living. Most of the future reduction in carbon emission will likely come from power

generation, which is the single biggest global emitter according to the IEA and the

cheapest one to reduce. Oil is a very competitive source of energy for transportation

purposes, and it will likely be around for many years. Even in IEA'ss most aggressive

scenario in terms of growth in alternative fuels, internal combustion engines will still

represent the majority of global engine sales over the next two decades. So, it would

take many decades for electric vehicles to get a big portion of the total fleet.

■ Why Is It So Good, Then? After getting into the details on how these moats are built

and how they become hard-to-overcome business protections, we get the sense that

they explain a lot of the past performance of the company in terms of profitability and

returns. It seems to us that the longer Ipiranga operates with such performance, the

harder it gets for the market to believe it can continue even further. This, of course,

reflects in the prices the market is willing to pay for the business. But we think that the

nature of these protections is such that time is more likely to reinforce them than to

weaken them. And their combination leads to what Charlie Munger calls "lollapalooza

effects," meaning that these moats produce synergic effects, as their combined impact

is stronger than the sum of their individual effect if each of them were present alone.

We believe this provides the basis for the discussion on margins presented in Question

#3.

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 20

Question #2: What Are the Prospects for Volume

Growth in Brazil?

"Brazil is a teenager. If you have a teenager living in your house, you know it can be chaotic. But the best decades for a teenager are still ahead." (Howard Marks)

Fuel Consumption in Brazil

■ Extreme Short-Term Focus. The market has focused a lot of attention on the recent

demand decrease taking place since 2015. We've seen the market, time after time,

overreact to a momentary negative business environment, in spite of the long history of

favorable fundamentals and potential for long-term growth. This happens when

performance is not evaluated over a long enough horizon. It reminds us of the words of

the psychologist and Noble Prize winner, Daniel Kahneman: "Too much concern about

how well one is doing in a task sometimes disrupts performance by loading short-term

memory with pointless anxious thoughts." We think monthly market figures are a huge

distraction to businesses with strong long-term prospects, as is the case of the

distribution business.

Does It Matter? The impacts of the current economic slowdown are very limited, in our

view. As we will discuss in Question #3, there are significant possible economies of

scale in this business, and volume growth matters. But short-term shortfalls shouldn't

matter too much, as far as long-term growth prospects are preserved. In Figure 20, we

show the demand deceleration movement in recent quarters that made many investors

concerned. In the words of Lee Kuan Yew: "If you do not know history, you think short

term. If you know history, you think medium and long term." Figure 21 shows the

impact on Ipiranga's valuation of different short-term demand scenarios. It makes the

case that, although next year's demand matters, it is, of course, the long term that

carries most of the weight in justifying the value of the business. By analyzing this

chart, investors can see that if something jeopardizes the prospects for long-term

demand growth, by reducing it, let's say, from 3% to 1%, then the business value

would decrease by almost 50%. In order to have the same effect on value, the short-

term volumes would have to decrease by c.35% in the first year, which is completely

out of proportion. Our team of economists already sees a short-term rebound in GDP

beginning next year, with GDP still contracting 3.8% this year but starting to recover

(+0.5%) in 2017.

Figure 20: History of Demand Fluctuations for

Diesel and Otto Cycle Fuels in Brazil in % YoY

Figure 21: Value Per Share Sensitivity to Short Term

and Long-Term Demand Growth in x

Source: Brazilian Oil, Gas, and Biofuels Agency (ANP), Credit Suisse analysis Source: Credit Suisse analysis

Diesel YoY

Otto YoY

-10%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

Q1 07 Q2 08 Q3 09 Q4 10 Q1 12 Q2 13 Q3 14 Q4 15

1.0x 1.1x 1.1x

1.3x 1.4x 1.5x

1.7x 1.8x 1.9x

1%

1%

2%

2%

3%

3%

4%

-6% -4% -2% 0%

Lo

ng

Te

rm V

olu

mes G

row

th

2016 Volumes Decline (YoY)

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 21

■ This Business Is Not for Short Termers. We believe that when investors are buying

Ultrapar, or particularly Ipiranga, they are buying an infrastructure and a strong position

in a market that will likely keep expanding over a long period. The business is capital-

intensive and, as such, materializes its value over the long run, especially in cases in

which scale grows over the years, consolidating an ever-higher business protection.

Even more so, if the company is successful in acquiring AleSat's network of stations

and logistics assets. The other side of this coin, and the good one, is that investors

don't have to bother trying to predict margin cycles or short-term demand dynamics, as

value is driven by long-term growth potential, as we've already discussed. As Howard

Marks once put it: "There is no such thing as THE time to go into a market. The

question is if this is A time to buy." So, the question becomes whether oil consumption

can still grow in Brazil for a prolonged period.

■ Developed versus Emerging. Over the past 25 years, consumption of oil products in

emerging economies has generally grown at significant rates, while we've seen this

trend actually in reverse in OECD countries, where demand has fallen as a result of

both lower economic growth and efficiency gains in fuel usage. In Figure 22, we depict

the historical variation (indexed in 1991) in consumption of oil products per capita in

some high consumer countries. In all of them, consumption either declined heavily or,

at best, stabilized at the same levels of 1991. Figure 23 depicts the same information

during the same period in some emerging economies, showing that per capita

consumption almost doubled in Brazil, and quadrupled in China in the period.

Increasing living standards promoted a sharp increase in consumption over a period of

more than 25 years.

Figure 22: History of Per Capita Consumption of

both Gasoline and Diesel (Selected Developed

Countries) Index (1991 = 1)

Figure 23: History of Per Capita Consumption of

both Gasoline and Diesel (Selected Emerging

Countries) Index (1991 = 1)

Source: EIA, World Bank, Credit Suisse analysis Source: EIA, World Bank, Credit Suisse analysis

■ But Per Capita Consumption Is Still Low. Despite more than two decades of high

demand growth rates, per capita consumption in emerging economies cannot yet even

approach the consumption levels of developed economies. As we can see in Figure

USA

France

Germany

Japan

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

1.1

1.2

1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012

Brazil

China

Mexico

0.7

1.2

1.7

2.2

2.7

3.2

3.7

4.2

1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 22

24, consumption in the US is around 40 barrels per day per thousand people, while

these same figures for other developed economies are in the high teens. The chart

also shows that all these countries decreased diesel and gasoline consumption per

capita since 2000. But, in spite of this decline, consumption in all those countries is still

much above what we see in Brazil, China, and Mexico, for example. In Figure 25, we

show that none of these three countries achieved 10bpd per thousand people yet.

More specifically, consumption in Brazil is still c.8bpd/thousand people, and in China,

c.4bpd/thousand people. We see this as a sign of undeveloped potential, as the

increase in consumption on a per capita basis takes many years to happen and comes

as a consequence of economic growth, social mobility, and increasing living standards.

Figure 24: Current Per Capita Consumption of both

Gasoline and Diesel (Selected Developed Countries) in bpd / thousand people

Figure 25: Current Per Capita Consumption of both

Gasoline and Diesel (Selected Emerging Countries) in bpd / thousand people

Source: EIA, World Bank, Credit Suisse analysis *Note: Last data available (US – 2014, remaining – 2013).

Source: EIA, World Bank, Credit Suisse analysis *Note: Last data available (Brazil – 2014, Mexico – 2013, China - 2012).

Diesel Consumption

■ Brazil Is Fueled by Diesel. One important driver of fuel consumption that we believe

will remain in place for a long time is the extremely high dependency of Brazil's

transportation matrix on road transportation. Considering other countries with large

territories, road transportation is more prevalent than other types of transportation

(such as railroads, pipelines, and waterways), since it allows for bigger scale and is

much cheaper for long distances. In Figure 26, we present the transportation matrix in

countries with large territories. Among the countries we analyzed, the share of road

transportation in the total cargo moved is generally much lower than 50%. In Brazil, it is

c.68%, with some variations depending on the information source. This level is closer

to what is observed in countries with much smaller areas, as shown in Figure 27.

42.5

24.1

21.1

17.4

40.6

18.5 17.5

14.0

USA Germany France Japan

2000

2014*

5.4

1.5

8.67.8

4.0

9.6

Brazil China Mexico

2000

2014*

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 23

Figure 26: Transportation Matrix of Countries with

Territories Larger Than 7MM Km² as of 2014* in % of tkm transported

Figure 27: Transportation Matrix Countries with

Territories Smaller Than 0.6MM Km² as of 2014 in % of tkm transported

Source: Federal State Statistics Service of Russia, National Bureau of Statistics of China, BTS (USA), Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (Australia), CNT and ILOS (Brazil), Credit Suisse analysis *Note: Last data available (US – 2011, Australia – 2012, remainder – 2014).

Source: Eurostat, Credit Suisse analysis Note: Information on share of pipelines was not available for these countries. Shares are ex-pipelines.

■ Small Railroads Coverage. It is remarkable how the usage of railroads for cargo

transportation is low in Brazil in comparison to other countries where there is equal

need to move goods over long distances. In Figure 28, we show this usage in volume

terms (tonne-kilometers, abbreviated as tkm) for other countries with large territories.

One related issue is of course the considerably small railroad infrastructure in Brazil

relative to other countries. In Figure 29, investors can find a metric of the railroad

coverage in different countries, with the figures in the circles representing the total area

of each country and the bars representing the ratio between the total length of railroads

available and the total area. Brazil has an area close to that of China and the USA, but

a "railroad coverage" of only c.10% of what is observed in those countries. The total

investment required to expand railroad infrastructure is, of course, very high, and that

is a barrier for this gap in the transportation matrix to be closed.

5%

32%

45%35%

68%

43%

18%

29% 46%

18%

3%

48%8%

19% 11%

49%

2%17%

3%

Russia China United States Australia Brazil

Road Rail Water Pipeline

80%

64%

85% 87%

16%

23%

15% 13%4%

12%

France Germany Italy United Kingdom

Road Rail Water

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 24

Figure 28: Transportation of Goods in Different

Countries and Volumes Moved by Railroad in 2014* in Btkm

Figure 29: Railroad Coverage in Different Countries

as of 2014 Railroad coverage in km/th sq km, areas in sq km

Source: Russia from Federal State Statistics Service, China from National Bureau of Statistics of China, United States from BTS, Australia from Department of Insfrastructure and Regional Development, Brazil from CNT and ILOS, , Credit Suisse analysis *Note: Last data available (US – 2011, Australia – 2012, remaining – 2014).

Source: ANTT, CIA The World Factbook, Worldbank, Credit Suisse analysis

■ New Rail Infrastructure May Come. In spite of the higher investments involved in

railroads, an expansion of the current coverage or an increase in the capacity of

existing infrastructure may represent a risk to future diesel demand growth, as a single

composition may be able to move the equivalent of what c.300 trucks could move. For

that reason, diesel consumption by railroads (c.4 cu m/Mtkm) is much more efficient

than consumption by trucks (c.42 cu m) for the same amount of cargo transported. In

Figure 30, we depict the average diesel consumption required to move one tonne of

cargo over one kilometer versus the total volume (in Btkm) transported by both

railroads and trucks in 2014. The product of these two variables (on the horizontal and

vertical axes) leads to the areas of the two rectangles, representing the total diesel

consumption per transportation mode in that year.

■ Would It Risk Future Growth Significantly? In the face of this high efficiency in

diesel consumption by railroads in relation to trucks, we thought it would be useful to

understand the impact on total consumption if railroads got a bigger share of the

transportation matrix. We provide in Figure 31 a sensitivity analysis, in which we show

how we think the total diesel consumption would behave as a function of the share of

railroads in cargo transportation. We drew a vertical line that represents where Brazil

stands today in terms of diesel consumption for transportation purposes. The chart

shows that, for diesel consumption to be hurt by, let's say, 10%, railroads' share of

cargo transportation would have to increase by c.44% relative to today. We think an

increase of this magnitude would take time to materialize and would also require lots of

capital to be deployed in new and existing railroad infrastructure.

2,945 2,777 2,128 261 307

13,053

6,715

2,787

309

1,384

China United States Russia Australia Brazil

Rail Others

32.1

20.5

5.3 4.8 3.6

9.1 9.4

16.4

7.7 8.4

USA China Russia Australia Brazil

Railroad Coverage (Km/th Km²)

Area (mn Km²)

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 25

Figure 30: Diesel Consumption by Road and Rail

transportation in 2014 in MCM

Figure 31: Diesel Consumption By Trucks And By

Railroads And Sensitivity To Higher Share of

Railroads in Transportation Matrix Consumption in MCM, share of railroads in % of tkm

Source: EPE, ANP, CNT, ILOS, Credit Suisse analysis Source: EPE, ANP, CNT, ILOS, Credit Suisse analysis

■ Would Local Rail Expansion Affect the Route of a Particular Crop? We were

particularly concerned about the potential reduction in diesel consumption that could

result from private investments in existing railways, especially those directly connected

to soy and corn production, which are concentrated in the Midwest region and

represent a high share of Brazilian agricultural exports. These two crops currently have

the two highest shares of rail transportation (after iron ore, of course, which alone

represents c.76% of total goods moved by rail). After new investments in capacity

expansion, rail might gain some share from trucks in the transportation of these two

crops. In Figure 33, we show how the total diesel consumed in transportation would be

affected by different shares of railroads in the transportation of soy and corn. It shows

that, only in an extreme and unrealistic scenario in which trucks would be left with none

of either product to transport, total diesel consumption would be affected by c.5%, at

most.

Figure 32: Share Of Different Cargoes In Railroad

Transportation (2011-2014) in % of tonnes

Figure 33: Diesel Consumption Sensitivity To

Higher Share of Railroads in Corn and Soy size of circles = diesel consumed in transportation in kbpd

Source: Brazilian Land Transportation Agency (ANTT), Credit Suisse analysis Source: Brazilian Energy Planning Corporation (EPE), Brazilian Oil, Gas, and Biofuels

Agency (ANP), Brazilian Land Transportation Agency (ANTT), Ministry of Development, Industry, and Foreign Trade (MDIC), Credit Suisse analysis

-

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

0 200 400 600 800 1,000 1,200

Consu

mptio

n p

er

freig

ht

tran

sport

ed

(m³/

mn t

on.k

m)

Freight transported (bn ton.km)

Rail

Road

47.7 mn m³

1.2 mn m³0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Die

sel c

onsu

mptio

n (

mn m

³)

Rail's share in freight transportation matrix (% of ton.km)

Consumption by RoadConsumption by Rail

0% 40% 60% 86%18% 26%

Current Total

Consumption

Consu

mptio

n b

y tr

uck

s

Consumption

by railroads

Scenario for 10%

Lower Diesel

Consumption

+44%

2.5%3.4%

76.0%

9.4%

3.7%

10.9%

Iron Ore Agricultural Metals & Mining Others

CornSoy

878 863 848 834 819

871 856 842 827 813

864 850 835 821 806

858 843 829 814 799

851 837 822 807 793

843

-25%

0%

25%

50%

75%

100%

-25% 0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Rail

share

in c

orn

tra

nsp

ort

aio

n

(% o

f to

n.k

m)

Rail share in soy transportation (% of ton.km)

35%

56%

22 June 2016

Ultrapar Participacoes SA (UGPA3) 26

■ Many Trucks, and Old Ones. Future economic growth will still depend a lot on trucks,

and therefore on diesel. Even more so if we consider that future growth will depend on

a truck fleet that is generally older than what we see in many countries. Figure 34

shows the age profile of different European countries and where the Brazilian fleet