Twenty-One—Month Follow-up Study of School-Age Children Exposed to Hurricane Andrew

Transcript of Twenty-One—Month Follow-up Study of School-Age Children Exposed to Hurricane Andrew

Twenty-One-Month Follow-up Study of School-AgeChildren Exposed to Hurricane Andrew

JON A. SHAW, M.D., BROOKS APPLEGATE, PH.D., AND CARYN SCHORR, M.D.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To explore the 21-month course of posttraumatic stress symptomatology (PTSS) and psychological morbidity

in 30 school-age children (7 to 13 years) after exposure to Hurricane Andrew. Method: Pynoos' Posttraumatic Stress

Disorder Reaction Index and Achenbach's Teacher's Report Form were administered at 8 and 21 months after Hurricane

Andrew. Results: At 21 months 70% of the children endorsed moderate-severe PTSS. The reduction in PTSS was

greater for boys than girls. Psychopathology as measured by the Teacher's Report Form increased over the 19-month

period. Boys demonstrated significant increases in internalizing symptoms and in Withdrawn, Anxious/Depressed, Social

Problems, and Attention Problems scales, and girls showed a significant increase in the Anxious/Depressed scale.

Conclusions: Twenty-one months after exposure to Hurricane Andrew, there were continuing high levels of PTSS and

evidence of increasing emotional and behavioral problems. While girls sustained higher levels of PTSS, boys demon

strated higher indices of other psychopathology. The enduring effects of disaster associated with secondary stressors

and "traumatic.reminders" continue to be etiologically important for continuing psychological morbidity. J. Am. Acad.

Child Ado/esc. Psychiatry, 1996, 35(3):359-364. Key Words: children, disaster, psychopathology.

The psychological effectsof natural disaster on childrenand adolescents have become an emerging focus ofstudy (Lipovsky, 1991). In recent years reports havebeen published on the psychological responses of children and adolescents to hurricane, fire, earthquake,and flood (Bloch et al., 1956; Bradburn, 1991; Burkeet al., 1986; Garrison et al., 1993; Green et al., 1991,1994; Honig et al., 1993; McFarlane et al., 1987;Newman, 1976; Pynoos et al., 1993; Shannon et al.,1994; Yacoubian and Hacker, 1989). The spectrumof posttraumatic stress symptomatology in childrenand adolescents generally parallels the psychologicalresponses of adults to overwhelming disaster. Acutepsychological responses to natural disaster includetrauma-specific fears, fears of recurrence, regressive

Accepted May 26, 1995.Dr. Shaw is Professor and Director, and Dr. Applegate isAdjunctAssistant

Professor, Division ofChildandAdolescentPsychiatry, Department ofPsychiatry,University ofMiami School ofMedicine. Dr. Schorr, a former childpsychiatryfellow in the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, is now in privatepractice.

Reprint requests to Dr. Shaw, University of Miami School of MedicineDepartment of Psychiatry D-29, P.O. Box 016960, Miami, FL 33101;telephone (305) 585-6862; fax: (305) 325-8355.

0890-8567/96/3503-0359$03.00/0©1996 by the American Academyof Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

J. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:3, MARCH 1996

behavior, externalizing symptoms, behavioral reenactment, posttraumatic play, avoidance of "traumaticreminders," detachment, anxiety and depressive disorders, school problems, symptoms of physiological hyperarousal, and changed attirudes about the self,world,and future (Bloch et al., 1956; Burke et al., 1986;Green et al., 1991, 1994; Newman, 1976; Pynooset al., 1987; Terr, 1981, 1983). Terr (1991) has suggested that psychological trauma associated with exposure to an overwhelming stressor is etiological for anumber of psychiatric disorders.

While there are a number of reports on the acutepsychological responses of children to disaster, thereis a relative absence of longitudinal studies. It is onlyrecently that investigators have begun to attempt todelineate between the short-term and long-term psychological effects associated with exposure to disaster(Lipovsky, 1991; Pynoos, 1993). Concurrently therehas been increasing attention focused on the psychological and psychiatric comorbidity found with the coreposttraumatic symptomatology (Breslau et al., 1991;Saigh, 1991; Sullivan et al., 1991). The question arises,is there a consistent configuration or pattern in theevolution of psychological and behavioral distress inthe postdisaster experience over time?

359

SHAW ET AL.

In an earlier article we reported on the psychologicaleffects of exposure to Hurricane Andrew on a schoolpopulation at 2 and 8 months. Sixty-two elementaryschool-age children (6 to 11 years) (HI-IMPACTschool) who were directly in the pathway of HurricaneAndrew were compared with a group of 44 childrennorth of Miami (Shaw et al., 1995). Eight weeksafter the hurricane, both groups were administered aninstrument measuring the degree of severity of exposureto the hurricane and Pynoos's Posttraumatic StressDisorder Reaction Index (PTSDRI). In addition, thestudents' primary classroom teacher completed anAchenbach's Teacher's Report Form (TRF) for eachchild. The PTSDRI and the TRF were repeated 32weeks after the hurricane.

We found that at 8 weeks, 85% of the children inthe HI-IMPACT school endorsed at least moderatelevels of posttraumatic symptomatology. At 32 weeksafter the hurricane, we were able to repeat the PTSDRImeasures on 47 of 62 children previously tested inthe HI-IMPACT school. Eighty-nine percent of thestudents were rated in the "moderate" and "severe"to "very severe" categories, which indicated continuingpsychological distress. We speculated that the initialhigh levels of posttraumatic stress symptomatologywere related to an "event trauma ," i.e., the impact ofHurricane Andrew, a stressor that was well circumscribed in time and associated with both bodily andlife threat. The continuing high level of posttraumaticstress symptomatology at 32 weeks, we believe, not onlywas related to the continuing exposure to "traumaticreminders" but also was due to the emergence of"process" trauma (Terr, 1991), i.e., an array of"secondary stressors" to include community and school disruption , flight of refugees, unemployment, and loss ofhome and logisticalsupport systems (Shaw et al., 1995).

One of the most interesting findings was the significant reduction in the manifestations of other emotionaland behavioral problems in the HI-IMPACT schoolimmediately after the hurricane, with a gradual rise inthese measures subsequently. Children in the pathwayof Hurricane Andrew manifested reduced indices ofpsychopathology as measured by the TRF across allscales relative to the comparison group. While thistrend was consistent, the findings were more significantfor girls. The boys demonstrated lower scores on theAnxious/Depressed scale, while the girls in the HIIMPACT school showed significantly lower mean

360

scores on the Internalizing and Externalizing globalscales, as well as Anxious/Depressed, Social Problems,Delinquent Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior, thanchildren in the comparison group.

This finding of reduced TRF indices of psychopathology in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Andrew was confirmed by other measures of reporteddisruptive behavior which were also significantly lowerin the HI-IMPACT school relative to the comparisongroup and the previous year's level of reported disruptive behavior in the HI-IMPACT school. We examinedthe relative risk of 21 disruptive behaviors reported tothe Dade County Public School Central Office forthe HI-IMPACT school and its respective educationaldistrict, for each grading period for the school yearafter the hurricane compared with the previous schoolyear. Disruptive behaviors measured included generaldisruptive behavior, defiance of school authority, disruption on the school bus, assault, theft , vandalism,battery on a student or staff member, fighting, robbery,continuous disruptive behavior, damaging school property, aggravated assault, use of provocative language,cutting class, dress code violations, excess unsatisfactoryabsences, being in an unauthorized location, leavingclasswithout permission, rude and discourteous behavior, excessive tardiness, and trespassing.

School-based disruptive behavior showed a markeddecrease in prevalence for the grading period immediately after the hurricane in the HI-IMPACT school,with a rebound effect 3 to 4 months after the hurricane.We speculated that this initial decline in observedpsychopathology was the result of a generic shocklike,numbing effect in the immediate aftermath of thehurricane which dampened the behavioral responsesto the disaster.

At the 32-week reevaluation, there were no statistically significant changes on the TRF scales for boysand girls, although the trend in means across all scalesevidenced a higher value at week 32 for both genders.

In an effort to explore further the evolution of thepsychological and behavioral effects in the postdisasterperiod, we have undertaken a 21-month follow-up ofthe elementary school-age children who were directlyin the pathway of Hurricane Andrew.

METHOD

Thirty of the original cohort of children who were initiallyevaluated at 2 and 8 months after Hurricane Andrew were adminis-

J. AM. ACAD . CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY. 35:3. MARCH 1996

HURRICANE ANDREW

46.746.7

6.6

305317

2-8 Months 2-21 Months

% Improved% No change% Worsened

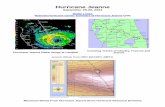

can be seen in this figure there is a progressive decreasein children rated in the severe-very severe categoryof posttraumatic stress symptomatology with slightchanges in the children rated in the moderate categorybut a twofold increase in children rated doubtful-mild.In essence there has been a cascading of children fromthe severe-very severe to the doubtful-mild category.At 21 months 70% of the children endorsed moderatesevere posttraumatic symptomatology.

The trend in posttraumatic stress symptomatologywas examined for statistical significance via CATMOD(SAS, 1990). A repeated-measures analysis (time: 2, 8,21 months posthurricane) with PTSDRI as the ordinaldependent variable revealed a statistically significanteffect for time (X2 [2, N = 29] = 13.82, P < .001),and post hoc follow-up indicated that the relativepattern in posttraumatic stress symptomatology didnot change between 2 and 8 months but did changebetween 2 and 21, and 8 and 21 months (p values< .01). Although the above analysis strongly implicatesa general group trend toward improvement, it doesnot adequately reveal how individual children's symptomatology changed. Table 1 presents individual patterns in posttraumatic stress symptomatology between2 and 21 months.

If one considers a clinically relevant level ofPTSDRIsymptomatology to be in the severe-very severe category, then it is also important to identify those childrenwhose condition seemed to get worse over the 19month period. While 17% (8) were worse at 8 months,only two continued to exhibit more posttraumaticstress symptomatology at 21 months than they did at2 months after the hurricane. Fifty percent of thechildren (4) who worsened at 8 months did so bymoving into the severe-very severe category. The children whose condition worsened over time would bean interesting sample for further study.

A similar set of analyses was conducted separatelyfor both boys and girls (Fig. 2). For boys, the same

TABLE 1Individual Patterns in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Reaction Index Symptomatology

21Months8 Months2 Months

~ 40+----

RcENT 20

The prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology at 2, 8, and 21 months is noted in Figure 1. As

I_NO.- Mild _Moderate III Severe I

Fig. 1 Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index symptomatology at 2, 8, and 21 months after Hurricane Andrew.

RESULTS

60,-------.,..-------,---------,

tered repeated measures at 21 months. Once again our measuresincluded the PTSDRI and the TRF.

The PTSDRI is an instrument designed to assess the degree ofposttraumatic symptomatology in children. Its items conform toDSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms andare rated on a 5-point ordinal scale from "none of the time" to"much of the time." A total PTSD score is obtained by summingacross all items after adjusting for reverse-scored items (Pynoos,personal communication). The PTSDRI was standardized on 750children and 1,350 adult casesof stress-laden events and has showna correlation of .91 with a positive PTSD diagnosis in children(Frederick, 1985). More recently, Shannon et al. (1994) andLonigan et al. (1994) used the PTSDRI in a study with morethan 5,500 children exposed to Hurricane Hugo. Shannon et al.(1994) reported high internal consistency values (ex = .83) for thefull instrument and values ranging from .55 to .86 for symptomclusters corresponding to the DSM-III-R Lonigan et al. (1994)provided validity evidence for the PTSDRI by demonstrating thatthe presence of PTSD symptomatology assessed by the PTSDRIwas strongly related to self-reported hurricane severity, degree ofhome damage, and continued displacement. Similarly, using our2-month posthurricane data, we estimated coefficient ex at .75,and the test-retest reliability between 2 and 8 months posthurricanewas .59.

The TRF requires classroom teachers to rate various studentbehaviors on a 3-point scale (not true, sometimes true, often true)and provides eight behavioral syndrome scale scores and twocomposite scale scores: Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, Anxious!Depressed, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Delinquent Behavior, Aggressive Behavior, and Internalizingand Externalizing, respectively. The TRF has been standardizedon 1,100 children aged 4 to 18 years (Achenbach and Edelbrock,1986), and studies have shown a mean test-retest reliability (15day retest interval) across various samples to be .92 (Achenbach,1991), while interteacher agreement was generally greater than .60(Achenbach, 1991). There have been a multitude of validity studiesinvestigating the TRF scales (refer to Achenbach [1991] for specificinformation regarding the construct and criterion-related validityof the TRF).

]. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:3, MARCH 1996 361

SHAW ET AL.

7'~--,-------,-------r-------,

PERCENT

I •Male • Female IFig. 2 Percentage of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Indexsymptomatology for males and females at 2, 8, and 21 months after Hurricane Andrew.

pattern of results as found in the combined samplewas observed. That is, there was an overall statisticallysignificant group decrease in PTSDRI symptomatology(X2 [2, N = 14] = 15.04, P < .0005) such that symptomatology at 2 months was not statistically different fromthat at 8 months bur symptomatology at 2 monthswas higher than at 21 months and symptomatologyat 8 months was higher than at 21 months (p values< .001). This trend, however, was not observed forgirls, in whom there was not a statistically significanteffect for time. The reduction in posttraumatic symptomatology was greater for boys than for girls.

The reduction in posttraumatic stress symptomatology over the 19-month interval is predominantly explained by boys, who experienced a decrease in thePTSDRI mean from 37.3 to 24.9 , while girls decreasedfrom 41.4 to 37.2.

We were able to obtain repeated measures on theTRF on 25 of the original sample. A comparison ofTRF scores for all subjects tested at 2 and 21 monthsis noted in Table 2.

There was an evident trend toward increasing psychopathology over the 19-month period. Several significant differences were found in subjects at 21 monthscompared with subjects at 2 months. At 21 months,compared with the immediate posthurricane period ,the boys demonstrated a significant increase in indicesof being withdrawn, being anxious/depressed, havingsocial problems, having attention problems, and in thegeneral category of internalizing symptoms (all p values< .05). Girls demonstrated a significant increase inthe dimension of anxiety/depression (p < .05).

362

TABLE 2Teacher's Report Form (T RF) Scales for Boys and Girls:

Analysis of the Mean Difference between 2 and 2 1 Monrhs

Male (n ~ 12) Female (n ~ 12)

T RF Scale Mean Diff. SD Mean Diff. SD

Wi thdrawn 1.75* 2.22 0.85 2.70Somatic Complainr 0.42 1.16 0.08 0.49Anxious/Depressed 3.42* 3.80 1.77* 2.52Social Problems 3.17* 4.61 0.46 1.45Thought Problems 0.67 1.67 0.46 0.97Attention Problems 7.25* 10.71 0.23 6.7 1Delinquenr Behavior 1.00 1.60 0.77 2.24Aggressive Behavior 7.08 13.55 1.92 6.81Inrern alizing Behavior 5.58** 5.86 2.69 4.61Externalizing Behavior 8.08* 14.79 2.69 8.51

* P < .05; **P < .01.

DISCUSSION

Our findings are in accord with the stud ies thathave demonstrated sustained and continuing psychological and behavioral responses associated with exposure to disaster (Bloch er al., 1956; Breslau et al.,1991; Garrison et al., 1993; Green et aI., 1991; Loniganet aI., 1994; Lyons, 1987; Newman, 1976; Pynooset aI., 1987; Shannon et al., 1994). Our finding that70% of the children continue to demonstrate moderateto very severe postt raumatic stress symptomatology 21months after the hurricane speaks to the enduringstressors associated with the secondary effects of thedevastation wrought by Hurricane Andrew and theoccurrences of "traumatic reminders."

Not only did we find persistent and sustained posttraumatic stress symptomatology, bur we found indicesof increased psychopathology over the 19-month period. In an earlier article, we found that children inthe immediate pathway of the hurricane demonstrateddecreased indices of psychopathology on the TRF anddiminished behavioral problems in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane compared with a comparisongroup bur that there was a subsequent rise in problembehaviors by the end of the year (Shaw et a1., 1995).In this study we demonstrated that 21 months afterthe hurricane there cont inue to be increased indicesof psychopathology for both boys and girls. At 21months compared with the immediate posthurricaneperiod, the boys demonstrated a significant increase inindices of being withdrawn, having social problems,having attention problems, being anxious/depressed ,and in the general category of internalizing symptoms .

] . AM. ACAD . CHILD ADOLESC. PSYC H IAT RY, 35:3, MARCH 1996

Girls demonstrated a significant increase in the dimension of anxiety/depression. It should also be noted thatthe largest increase in teacher ratings was for boys'externalizing symptoms, but this increase also camewith a vety large standard deviation, thus mitigatingits statistical significance.

Pynoos (1993) has noted that the long-term posttraumatic stress-related pathologies include "chronicPTSD, comorbid mental and physical conditions, developmental and personality disturbances, and age appropriate indications of dissatisfactions and lack of wellbeing" (p. 231). In follow-up studies of children afterthe Buffalo Creek disaster, Green et al. (1991, 1994)noted that 2 years after the disaster, 37% of the childrenand adolescents were given a "probable" diagnosis ofPTSD, and 17 years after the disaster 7% of thosereevaluated had PTSD and all of these individuals werewomen. Green et al. (1991) found that the risk factorsthat best predicted continuing posttraumatic symptomatology was degree oflife threat, parental psychopathology, being female, and an irritable and/or depressedfamily atmosphere. Honig et al. (1993) observed thatthere was a spectrum of "adaptational possibilities"found in children 20 years after the Buffalo Creekdisaster which were related to the family's initial response to the disaster and that psychopathology in thechildren resonated with parental psychopathology.

Our finding that comorbid psychological and behavioral distress was lower than in a comparison groupin the immediate aftermath of the hurricane but increased over time is similar to findings of studiesof the children exposed to an Australian bush fire(McFarlane et al., 1987). The authors demonstratedthat children 5 to 12 years of age who were exposedto a bush fire manifested increased rates of psychiatricdisorders 8 and 26 months after the disaster. McFarlane(1987) speculated that the increased risk for psychiatricdisorder in children over time was related to increasingfamily dysfunction. Other studies have demonstratedincreased behavior and psychological distress in theposttraumatic experience. Breton et al. (1993) foundthat a year after an industrial accident, children aged6 to 11 years displayed more overall internalized andposttraumatic symptoms than did a control group.

The continuing high level ofPTSDRI symptomatology as well as increasing levels of psychological andbehavioral distress at 21 months, we believe, are relatedto the emergence of a "process" trauma (Terr, 1991).

]. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:3, MARCH 1996

HURRICANE ANDREW

This may best be interpreted as exposure to an arrayof enduring "secondary stressors" such as traumaticreminders, continuing adversity, and demoralization.The effectof the hurricane was to destroy the infrastructure of a community, resulting in high unemployment,family dwellings rendered uninhabitable, the exodusof a large proportion of the population, and the lossof electricity, telephones, and logistical support systemsfor many months. The initial hopefulness of recoveryafter the input of federal resources was followed byincreasing pessimism as families struggled with theinherent adversarial relationship with insurance companies, contractors, and code inspectors; unemployment;and the "loss of community." The devastating effectsof natural disaster on the infrastructure ofa communitywith subsequent psychosocial adversity for its inhabitants has been well documented (Adams and Adams,1984; Erikson, 1976; Lifton and Olson, 1976).

It is our hypothesis that the impact of the "event"stressor was quickly followed by the enduring impactof an array of chronic stressors as the communitybegan the slow process of recovery and reparation. Theincreasing spectrum and frequency of emotional andbehavior problems in the children as the school yearprogressed resonated with this process.

The finding that girls demonstrated a smaller reduction in the level of posttraumatic symptomatology overtime is congruent with the literature. A number ofstudies have demonstrated that being female is a riskfactor for PTSD and that being female predicts slowerrecovery from PTSD (Breslau et al., 1991; Garrisonet aI., 1993; Green et al., 1991; Shannon et aI., 1994).It is particularly interesting to note that while girlssustained higher indices of posttraumatic stress symptomatology over the 19-month period and a slowerincrease in other indices of psychopathology on theTRF, boys showed a greater reduction in posttraumaticstress symptomatology but a greater increase in TRFreported psychopathology. This suggests that whileboys were able to move away from a preoccupationwith the hurricane, the psychological distress becamemanifested in other ways. While there are genderdifferences in expression, it is apparent that psychological stress remains high in the aftermath of HurricaneAndrew. It is evident that while a disaster may bewell circumscribed in time and quickly dissipates, theenduring effects associated with the destruction of acommunity, the secondary stressors, and the "traumatic

363

SHAW ET AL.

reminders" continue to have an impact on the victimsof disaster.

These results support the general finding of continuing and sustained moderate levels of posttraumaticstress symptomatology and suggest that after a naturaldisaster there may be increasing psychopathology inchildren. It is important to note the limitations associated with small sample sizes and the limited generalizability because of the idiosyncratic nature of thecircumstances of natural disaster and its derivativeeffects on the infrastructure of a community.

REFERENCES

Achenbach TM (l99I), Manual fOr the Teacher's Report Form and 1991Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Deparrment of Psychiatry

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C (l986), ManualfOr the Teacher's Report Formand TeacherVersion ofthe Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: Universityof Vermont Department of Psychiatry

Adams PR, Adams GR (l984), Mount St Helen's ashfall. Am Psychol39:252-260

Bloch DA, Silber E, Perry AB (l956), Some factors in the emotionalreaction of children to disaster. Am] Psychiatry 113:416-422

Bradburn IS (l99I), After the earth shook: children's stress symptoms 6-8months after a disaster. Adv Behav Res Ther 13:173-180

Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E (l99I), Traumatic eventsand post-traumatic stress disorder in an urban population of youngadults. Arch Gen Psychiatry48:216-222

Breton JJ, VallaJP, Lamberr J (l993), Industrial disaster and mental healthof children and their parents. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry32:438-445

Burke J, Moccia P, Borus J, Burns B (1986), Emotional distress in fifthgrade children ten months after a natural disaster. ] Am Acad ChildPsychiatry25:536-541

Erikson K (1976), Loss of community at Buffalo Creek. Am] Psychiatry133:302-305

Frederick C] (l985), Children traumatized by catastrophic situations. In:Post-Traumatic StressDisorder in Children, Spencer E, Pynoos RS, eds.Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press

Garrison CZ, Weinrich MW, Hardin SB, Weinrich S, Wang L (l993),Post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents after a hurricane. Am]EpidemioI136:522-530

Green BL, Grace MC, Vary MG, Kramer TL, Gieser GC, Leonard AC(l994), Children of disaster in the second decade: a 17-year follow-upof BuffaloCreek survivors.]Am Acad Child AdolescPsychiatry33:71-79

364

Green BL, Korol M, Grace M et al. (l99I), Children and disaster: age,gender, and parental effects on PTSD symptoms. ] Am Acad ChildAdolesc Psychiatry 30:945-951

Honig RG, Grace MC, Lindy JD, Newman C], Titchener JL (l993),Portraits of survival: a twenty year follow-up of the children of BuffaloCreek. PsychoanalStudy Child 48:327-356

Lifton RJ, Olson E (l976), The human meaning of total disaster. Psychiatry 39:1-17

LipovskyJA (l991), Children's reaction to disaster: a discussion of recentresearch. Adv Behav Res Ther 13:185-192

Lonigan C], Shannon MP, Taylor CM, Finch AJ jr, Sallee FR (l994),Children exposedto disaster:II. Risk factorsfor the development of posttraumatic symptomatology.]AmAcad ChildAdoles Psychiatry33:94-105

Lyons JA (l987), Postraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents:a review of the literature. ] Deu Behav Pediatr 8:349-356

McFarlane AC (l987), Family functioning and overprotection followinga natural disaster: the longitudinal effects of post-traumatic morbidity.Aust N Z] Psychiatry 21:210-218

McFarlane AVe, Policansky S, Irwin CP (l987), A longitudinal study ofthe psychologicalmorbidity in children due to a natural disaster. PsycholMed 17:727-738

Newman C] (l976), Children of disaster: clinical observations at BuffaloCreek. Am] Psychiatry 133:306-312

Pynoos RS (l993), Traumatic stress and developmental psychopathologyin children and adolescents. In: Review ofPsychiatry, Oldham JM, RibaMB, Tasman A, eds. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press,pp 205-238

Pynoos R, Goenjian AK, Karakashian M et al. (l993), Post-traumaticstress reactions in children after the 1988 Armenian earrhquake. Br]Psychiatry 163:339-347

Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K et al. (l987), Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44:1057-1063

Saigh PA (l991), The development of post-traumatic stress disorder following four different types of traumatization. Behav Res Ther 29:213-216

SAS (l990), SAS/STAT Users Guide, Vol I, version 4th edition. Carey,NC: SAS Institute, pp 405-518

Shannon MP, Lonigan C], Finch AJ Jr, Taylor CM (l994), Childrenexposed to disaster: 1. Epidemiology of post-traumatic symptoms andsymptom profile. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry33:80-93

Shaw JA, Applegate B, Tanner S et al. (1995), Psychological effects ofHurricane Andrew on an elementary school population. J Am AcadChild Adolesc Psychiatry34:1185-1192

Sullivan MA, Saylor CF, Foster KY (1991), Post hurricane adjustment ofpre-schoolers and their families. Adv Behav Res Ther 13:163-171

Terr LC (l981), Psychic trauma in children: observations following theChowchilla bus kidnapping. Am] Psychiatry 138:14-19

Terr LC (l983), Chowchilla revisited: the effectsof trauma four years aftera school bus kidnapping. Am] Psychiatry 140:1543-1550

Terr LC (l991), Childhood trauma: an ourline and overview. Am ]Psychiatry 148:1-20

Yacoubian VV, Hacker FJ (l989), Reactions to disaster at a distance. Thefirst week after the earrhquake in Soviet Armenia. Bull MenningerClin 53:331-339

J. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:3, MARCH 1996