Truth and Pwer, Monks and Technocrats - Wallace

-

Upload

alex-cheirif -

Category

Documents

-

view

182 -

download

0

Transcript of Truth and Pwer, Monks and Technocrats - Wallace

Truth and Power, Monks and Technocrats: Theory and Practice in International RelationsTwo Worlds of International Relations: Academics, Practitioners and the Trade in Ideas byChristopher Hill; Pamela Beshoff; Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-Making: NationalPerspectives on Academics and Professionals in International Relations by Michel Girard;Wolf-Dieter Eberwein; Keith Webb; Bridging the Gap: Theory and Practice in Foreign Policyby Alexander George; Rethinking International Relations by F ...Review by: William WallaceReview of International Studies, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1996), pp. 301-321Published by: Cambridge University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20097450 .Accessed: 15/06/2012 21:17

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Review ofInternational Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

Review of international Studies (1996), 22, 301-321 Copyright ? British International Studies Association

Truth and power, monks and technocrats:

theory and practice in international relations

WILLIAM WALLACE*

Christopher Hill and Pamela Beshoff (eds.), Two Worlds of International Relations:

Academics, Practitioners and the Trade in Ideas, London, Routledge, 1994

Michel Girard, Wolf-Dieter Eberwein and Keith Webb (eds.), Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making: National Perspectives on Academics and Professionals in International

Relations, London, Pinter, 1994

Alexander George, Bridging the Gap: Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy, Washington, DC, US Institute of Peace, 1993

Fred Halliday, Rethinking International Relations, London, Macmillan, 1994

Walter Carlsnaes and Steve Smith (eds.), European Foreign Policy: The EC and Changing Perspectives in Europe, London, Sage, 1994

Ken Booth and Steve Smith (eds.), International Relations Theory Today, Cambridge, Polity, 1995

'The study of international relations is not an innocent profession.'1 It is not like the

classics, or mathematics, an abstract logical training for the youthful mind. The

justification for the place it has gained in the university curriculum rests upon utility, not on aesthetics. The growth of the social sciences in Western universities in the

past century, and their remarkable expansion over the past thirty years, has been

based upon their perceived contribution to better government, in the broadest sense.

'The forever explosive relationship between social science and public policy' has been

embedded in the discipline of International Relations from the outset.2

The establishment of International Relations as an academic discipline was, more

specifically, a response by liberal optimists (primarily in Britain and the United

States) to the First World War, hoping through education and information to bring * This essay began as a review article on recent studies of the relationship between academics and

practitioners in international relations. An invitation to address the annual conference of the British

International Studies Association in December 1994 led to its expansion into a broader survey of the

underlying issues at stake and of recent British and other European discussions of the tensions

involved. I am grateful to Troy Mcgrath and Andrew Hurrell, Ralf Dahrendorf, and Theodore Lowi

for help respectively in picking my way through debates on international relations theory, on the

relationship between intellectuals and society, and on debates within American political science on

political responsibility and relations with policy-makers; and to Anne Deighton, Robin Niblett, Julie

Smith and Helen Wallace for comments on a preliminary draft. 1 James Cable, The Useful Art of International Relations', International Affairs, 61:2 (April 1985), p. 305. 2 Ralf Dahrendorf, LSE: A History of the London School of Economics, 1895-1995 (Oxford, 1995), p. v.

Dahrendorf's account of the development of the social sciences in London also stresses the constant

tension between empiricists like Webb and Beveridge?with their faith in 'facts'?and theorists like

Mannheim, von Hayek, Popper and Oakeshott.

301

302 William Wallace

reasoned debate into politics and policy-making. Its development as a discipline was

shaped by the turbulent international politics of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, by the Second World War and the direct but diverse experiences of those caught up in

that war who dominated academic International Relations until the end of the

1960s. The generation which passed through universities in the 1960s, now at the top of the profession, were marked in their turn by their diverse responses to nuclear

deterrence, American hegemony, and the Vietnam War. The rising generation now

passing through undergraduate and graduate education start from their experience of a world in which the Cold War is history, in which the juxtaposition of a pro liferation of new states claiming sovereignty and of increasing evidence of the

endemic weakness and incapacity of states presents a central paradox. Struggle as we may to avoid the dangers of 'presentism' and of current events, we are all child ren of our time: attempting to reconcile our own experience and understanding of the world with our interpretation of history, philosophy, psychology and morality.

International Relations as a discipline grew out of reflections on policy, and out of

the desire to influence policy, or to improve the practice of policy. The distinction between the academic theorist and the practical policy-maker was a matter of

degree: a degree of detachment from day-to-day practical concerns, but not a denial

that those day-to-day concerns were relevant or real. Both Two Worlds of Inter

national Relations and Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making raise the

question of what relationship this now adult discipline should aim to have with the

world of policy and practice out of which it grew. Both reflect the underlying tension involved in the relationship between the scholar and the policy-maker, between the seeker after truth and the holder of power. Christopher Hill fears that

the two worlds have moved 'closer together', and suggests that it is time to move

further apart: 'to build on traditions of thought which are at one remove from

events, and to work in that much-derided ivory tower which provides the freedom to

be eccentric'.3 This image of an academic world at once tempted and threatened by contacts with the policy world?'the siren song of policy relevance' (the title of

Hill's introductory chapter) pulling an independent discipline away from its proper concerns?recurs throughout the literature under review.

Brief reflection on the careers of those who established the postwar discipline in

Britain, after wartime military or civilian service, however suggests that the academic world has moved away from government rather than towards it.4 A generation ago those interested in theoretical approaches to international relations in Britain were

few enough to meet round a college high table, bringing together professional diplo mats, historians, philosophers, even theologians to debate and define their concept of

international society.5 The construction of a self-conscious British academic

3 Hill and Beshoff (eds.), Two Worlds, pp. 3, 223. 4

Martin Wight was, as a pacifist, an exception to the many who fought or worked in military

intelligence in World War II. But his approach to international politics was nevertheless moulded by his attempts to understand and explain the crises which led to the Second World War. His chapter on

'The Balance of Power' in the Chatham House survey volume, The World in March 1939 (London,

1950) follows his chapters on Eastern Europe and Germany, with their detailed examinations of Nazi, Fascist and Leninist assumptions about international relations, and their critique of the liberal

approach. 5

Timothy Dunne, 'International Relations Theory in Britain: The Invention of an International Society Tradition', DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 1993, describes the work and meetings of this 'British Committee on the Theory of International Polities'.

Truth and power 303

discipline dates only from the 1960s.6 International Relations courses are now

offered at over fifty British universities, with strong groups of International

Relations scholars?even separate departments?across the country, in contrast to

the isolated teachers and pockets of expertise of thirty years ago.7 Professionaliza

tion has brought with it separation from related disciplines, and specialization within

the discipline itself. A rising proportion of those teaching International Relations in

British universities today were trained from their undergraduate studies onwards in

International Relations, and have spent their professional lives entirely within an

academic environment?the first generation to share such a professionally self

contained intellectual formation.

There is a tendency for all academic disciplines to demonstrate their intellectual

standing in the university by privileging theoretical studies over applied. This ten

dency has been particularly evident in the social sciences, as they struggled to gain

respect from disdainful classicists, philosophers and natural scientists. Economic

theorists, as they confidently look mathematicians in the eye, look down on trans

port economists and labour economists; social theorists patronize those who teach

social policy and administration. American political science has attempted to follow

the quantitative-mathematical path toward science, in the 1960s through behav

iouralism, in the 1980s and 1990s through game theory and rational choice.

Sociology has followed the philosophical path, refining theories and meta-theories to

the neglect of engagement with social problems or empirical work.8

International Relations as a British discipline in the mid-1990s appears torn

between following the path which sociology has taken and maintaining a dialogue with the broader political debate. The evidence of Keith Webb's 1991 survey of

BISA members suggests that the majority of IR academics 'feel that their expertise should be used more' and would like to have 'more meetings between the academics

and the professionals'.9 The evidence of the academic journals, and of many of the

contributors to other books under review, suggests a deep ambivalence about

contacts with the world of policy and politics, extending for some to deliberate self

exclusion through enclosure within 'what often appears an arcane and incestuous

debate'.10

The aim of this article is to consider the appropriate degree of detachment or of

engagement which academics in International Relations should practise towards

the policy arena. I do not wish to suggest that there should be any uniformity of

approach. Our discipline, like other social sciences, should demonstrate a healthy and tolerant diversity: of theoretical approaches, of relations with policy-makers versus concentration on fundamental questions, of detailed studies alongside broad

6 Hedley Bull remarked that, when he arrived at the LSE as an assistant lecturer in 1956, T had not

done a course of any kind in International Relations, nor made any serious study of it, and as I

arrived at Houghton Street I wondered how I was to go about teaching the subject and even whether it

existed at all.' Bull, 'Martin Wight and the Theory of International Relations', British Journal of International Studies, 2:1 (1976), p. 101.

7 Until the mid-1960s the LSE and Aberystwyth were the only two effective departments of

International Relations in Britain. Some seminars and tutorials were given at Oxford, but the professor of International Relations was inactive.

8 See the exchange between David Walker and Mich?le Barrett (President of the British Sociological

Association) in Times Higher Education Supplement, 17 March and 12 May 1995. 9 Keith Webb, 'Academics and Professionals in International Relations: A British Perception', ch. 7 in

Girard et al., Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making, pp. 90-1. 10

Ibid., p. 93.

304 William Wallace

historical surveys. The establishment of hegemonic 'schools', imposing tests of

orthodoxy for academic appointments, has damaged American social sciences, in

cluding American political science and International Relations. I do however want

to suggest that the balance between detachment and engagement, between with

drawal behind the monastic walls of the university and the joys and dangers of

mixing with the profane world outside, has tipped too far: that International

Relations as a British discipline has become too detached from the world of practice, too fond of theory (and meta-theory) as opposed to empirical research, too self

indulgent, and in some cases too self-righteous. I also want to suggest that as a

discipline we have become remarkably unselfconfident about our own theoretical

development, remarkably derivative of American theorizing and intellectual

fashions?except for those who have preferred to follow Parisian intellectual

fashions. We neglect the international relations of our own European region, with all

its turmoil, to grapple with academic debates which derive from an Americocentric

understanding of the world.

The political responsibility of intellectuals: our three audiences

Politics and scientific study, as Max Weber argued in the formative years of social

science, are different vocations, with different codes of moral responsibility.11 There

is an unavoidable tension between the two worlds, requiring a high degree of self

consciousness in those who move from one to the other or work across the

boundaries between the two. But they are not entirely separate; intellectual res

ponsibility shades into irresponsibility when the intellectual disclaims engagement with the world within which she or he lives.12 Hans Morgenthau, the great postwar

protagonist of Realism, consciously followed Weber in his reflections on the co

option of American social scientists into 'the academic-political complex' which led

the United States into the Vietnam quagmire.

The intellectual lives in a world that is both separate from and potentially intertwined with that of the politician. The two worlds are separate because they are oriented towards different

ultimate values ... truth threatens power, and power threatens truth.13

Behind the particular dilemmas which face the expert on international relations lie

the broader questions of what is the proper relationship between the intellectual and

11 'Politics as a Vocation', 'Science as a Vocation', lectures originally delivered in Munich University in

the traumatic conditions of the winter of 1918; published in translation in the aftermath of World War

II in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, ed. H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Oxford, 1946). 12 The discussion in Ian Maclean, Alan Montefiore and Peter Winch (eds.), The Political Responsibility of

Intellectuals (Cambridge, 1990) ranges from Plato and Seneca to the present day, while focussing

primarily on the dilemmas faced by intellectuals in Central and Eastern Europe under socialism over

the past forty years. Timothy Garton Ash, 'Prague: Intellectuals and Politicians', in The New York

Review, 12 January 1995, provides a fascinating discussion of the dilemmas facing intellectuals who cross the divide without admitting the necessarily different discourses of the two worlds?with

particular reference to Vaclav Havel and Vaclav Klaus. For an alternative and uncompromising view, see Noam Chomsky, The Responsibility of Intellectuals', reprinted in John Vasquez (ed.), Classics of International Relations (Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1990).

13 Hans J. Morgenthau, Truth and Power: Essays of a Decade, 1960-70 (London, 1970), p. 14; quoted by

Christopher Hill as the departure point for Hill and Beshoff (eds.), Two Worlds.

Truth and power 305

society, the university teacher and the state: important theoretical and practical

questions which university teachers in Britain (and in other countries) are

remarkably reluctant to address. What is the relative importance of the three

different audiences for which we write and speak: our colleagues, our students, and

the wider public? Does the intellectual have a duty to all three audiences?to educate a wider group than her own students, even to contribute to raising the quality of

debate in society as a whole, to the questioning of the established conventional

wisdom? If so, how should she fulfil that duty? In teaching our students, are we

concerned to train them to understand and operate in the world of politics and

policy, with all its grubby compromises; or rather to emancipate them from the

conventional assumptions around which national and global politics revolve, with

out regard for their future prospects or careers? Do we see ourselves as educating a

rising generation of subversive 'free intellectuals', of Bohemian taxi-drivers; or as

providing future diplomats, national and international officials, aid-workers and

others aiming for careers beyond national boundaries with a more self-conscious

and enlightened understanding of the constraints within which they may have to

work?14

The question of which audiences we seek to address also relates to the style in

which we express ourselves, and the vehicles which we choose for publication. 'Not a

few policy specialists exposed to the scholarly literature', Alexander George reports from his largely American experience, 'have concluded that most university pro fessors write largely for one another and have little inclination or ability to

communicate their knowledge in terms comprehensible to policymakers.'15 The culti

vation of complex language, of obscure terminology accessible only to those already

deeply immersed in the specialist literature, is a justifiable tendency only in

theoretical writing within specialist journals. Our student audience?at least, our

undergraduates?need something more straightforward; and a wider audience will

remain beyond reach unless addressed in terms which they can understand without

too much difficulty. Max Weber spoke as a Beamte, a privileged official of the German state arguing

for a degree of detachment from that state while also recognizing his broader res

ponsibility to state and society. British academics lack the official or social status

which German professors still retain; but, uncomfortable as we may find it, we also

depend for our incomes primarily on the public budget. Do we in our position have a duty to our state, as well as to our society, in return for the degree of detachment

(and the modest salaries) which we are granted? I hold that we owe a duty of constructive and open criticism: to speak truth to

power, not to hide our knowledge in obscurely erudite terminology, nor to lose

ourselves in scholastic word games, nor to speak truth in secret only to each other.

The passion with which critical theorists proclaim that 'the point of International

Relations theory is not simply to alter the way we look at the world, but to alter the

world' is negated by the absence of a strategy for communicating such theories to

14 Edward Shils, 'Intellectuals and Responsibility', in The Political Responsibility of Intellectuals, notes

the nineteenth-century development of an oppositional 'free intellectual' Bohemian class, members of

which 'slipped into ... confederation with anarchists and revolutionary socialists' (p. 292). A seminar series on careers for graduate students in political science at the University of Freiburg, in November

1994, was advertised as 'Alternatives to taxi-driving'. 15

George, Bridging the Gap, p. 7.

306 William Wallace

the world.16 'If, Stephen Chan asks in Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making, 'in the face of what seem impossibilities, there is a retreat into introspection, perhaps into an exemplary "life as art" syndrome?much beloved by the interviewers and

biographers of Foucault?then the question is simply, "exemplary for whom, on

behalf of what?"' But he fails to answer his own question, calling only for con

tinuing intellectual 'struggle' in solidarity with the oppressed, and for 'a refusal to

act as a priest class that mediates between rulers and ruled'.17

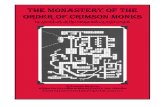

Images of purity and contamination, of salvation and damnation, even of

'academic virginity' and of the fallen intellectual seduced by 'the siren song of policy relevance', recur throughout the literature, old and new.18 'One has only to identify those practices which we most abhor in International Relations? the temptations of international history, the virus of "presentism", the corruption of "current

affairs"?to see how deepseated this concern about external contamination is'.19 In

his account of the tensions which tore the LSE apart in 1968, David Martin writes of the underlying divide between 'monks' and 'technocrats'. The latter saw the LSE as inherently involved with the world around it, while the former 'were careful

scholars and in accordance with an ancient vow of intellectual chastity bent all their

energies to make their studies pure ... Anything which was "applied" smacked of the

Great City and contravened the ancient vow' 20

The intellectual class in modern society does, after all, fulfil the functions that

prophets, priests and scribes fulfilled in pre-modern systems: of interpreting signs and symbols, of communing with the infinite, of looking beyond the immediate concerns of day-to-day life, of providing frameworks to reduce the chaos of

experience to understandable shape.21 But priests and monks in medieval Europe

positioned themselves at different points between the enclosed monastery and the

corruption of the worldly city. Some (like St Anthony of Egypt as depicted in

medieval paintings) rejected any contact with the world, to retire to the desert to

16 Mark Hoffman, 'Critical Theory and the Inter-paradigm Debate', Millennium 16:2 (1987), p. 244, cited in several of the volumes under review.

17 Stephen Chan, 'Critical Theory, Praxis and Postmodernism', ch. 3 in Girard et al., Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making, pp. 32-3. Edward Said, in Representations of the Intellectual (London, 1994), is similarly ambivalent about the role of the intellectual in contemporary society. For him, the

archetypical intellectual is an individual, a heroic, charismatic figure whose duty it is to choose to side

with the oppressed against the corruption of power. But he also recognizes that the golden age of the heroic intellectual (he mentions Russell, Sartre, Debray and Chomsky) has passed; university

expansion and the professionalization of the intellectual class has transformed his position. He

identifies three possible positions for the intellectual to take towards power: to justify and legitimize power, to stand 'in metaphorical exile' as a witness against power, or to act as a constructive critic.

'The alternatives are not total quiescence or total rebelliousness', he notes (p. 52). Yet he still wavers

between preferring the role of the prophetic outsider and that of the critical insider?the prophet or

the priest. 18 Bertil Nygren, in Girard et al., Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making, p. 107, regrets the loss of

'the academic virginity' of the Swedish Institute of International Affairs in its relations with the

Swedish ministries of defence and foreign affairs. 19 Fred Halliday, 'The End of the Cold War and International Relations: Some Analytic and Theoretical

Conclusions', ch. 2 in Booth and Smith (eds.), International Relations Theory, p. 39. 20 David Martin, 'The Dissolution of the Monasteries', in Martin (ed.), Anarchy and Culture: The

Problem of the Contemporary University (London, 1969), p. 1; cited in Dahrendorf, LSE, p. 417. 21 Karl Mannheim, 'The Sociological Problem of the "Intelligentsia" ', in Mannheim, Ideology and

Utopia (New York, 1936), pp. 156-64; Edward Shils, The Intellectuals and the Powers (Chicago, 1972). See also Said, Representations of the Intellectual, p. 27, citing Shils, Julien Benda and Antonio

Gramsci; Benda's classic 1927 treatise, La trahison des clercs, took as its starting-point the assumption that intellectuals were a class apart with a sacred vocation.

Truth and power 307

struggle with their conscience and their God, and to fight imagined devils on behalf

of unknowing sinners. Others accepted the Benedictine task of prayer and educa

tion, offering hospitality to passing travellers and occasional assistance to the tem

poral power. Others, Dominicans and Jesuits, allied with earthly authority and

fought on its behalf to impose orthodoxy on heretics. Yet others, Franciscans, set

out to preach to the poor a gospel critical of authority but not destructive of

authority as such, with all the risks which the Franciscans ran of being condemned as heretics when the gospel they preached displeased those currently in power. Ralf

Dahrendorf, following David Martin, refers to the 'London School of Friars'.22

How pure should we aim to be, how secure from the contamination of the wicked

(though luxurious) policy world? Chan notes that the saving remnant of the New

Left Review

was famous or infamous for its internal struggles predicated on purity and on who was purer

than whom. Perry Anderson used to fulminate against those who dared to write for

compromised papers such as the Guardian, the New Statesman, even Marxism Today.23

But if we cling to our intellectual chastity and reject such compromised vehicles of

communication, we are unlikely to reach much of an audience. It is wonderfully ambitious to proclaim that 'world politics is the new metaphysics, a global moral

science' through which we will 'reinvent the future ... freeing people, as individuals

and groups, from the social, physical, economic, political and other constraints

which stop them carrying out what they would freely choose to do'.24 It falls far

short of that ambition to communicate with the people of the world primarily

through Millennium or the Review of International Studies, or even through the

university lecture hall and tutorial. Sectarianism?to switch from a Catholic to a

Protestant metaphor?is a besetting sin of academic life, each exclusive group self

righteously insisting that it has discovered the path to truth and salvation.25 Ken

Booth's concluding chapter to International Relations Theory Today has all the

power and passion of an evangelical sermon, reminding its sinful readers that 'the

enemy is us', calling on us to repent of our consumerist culture of contentment and

to 'ask the victims of world politics to reinvent the future'.26 The discourse of postmodernist and critical theorists tells us much about their

own self-closure to the world of policy. 'Dissidence' and 'resistance' are powerful words, implying that the writers live in truth (as Havel put it) in a political system based upon lies; drawing a deliberate parallel with the dissidents of socialist central

Europe, as if these Western 'dissidents' had also to gather secretly in cramped

apartments to hear a lecturer smuggled in from the free universities on the 'other'

side?Noam Chomsky, perhaps, or Edward Said, slipping into authoritarian

22 Dahrendorf, LSE, p. 421. St Antony's College, Oxford, takes as its patron not the hermit Egyptian saint but St Anthony of Padua, the most eloquent and scholarly preacher of the first generation of

Franciscans. One recent biographer notes that St Anthony of Padua's intellectual reputation was

however eclipsed 'just a few years after his death' by the rise of 'the theological and philosophical movement of Scholasticism'. Vergilio Gamboso, Life of St. Anthony (Padua, 1979), p. 143.

23 Girard et al., Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making, p. 32. 24

Ken Booth, 'Dare not to Know: International Relations Theory versus the Future', in Booth and

Smith (eds.), International Relations Theory Today, pp. 328, 340, 344. 25 Gabriel Almond, A Discipline Divided: Schools and Sects in Political Science (Newbury Park, CA,

1990). 26

Booth, 'Dare not to Know', pp. 344, 348.

308 William Wallace

Britain.27 Chomsky may have been, for some in the 1970s and 1980s, 'the prophet for

whom so many of our younger generation yearn'?though Max Weber, who went on

to warn that 'academic prophecy ... will create only fanatical sects but never a

genuine community', was referring to a much earlier rising generation.28 The terminology of dissidence and exile is drawn from the post-Vietnam image of

an authoritarian and capitalist America, in which hegemonic Harvard professors suppress the views?and stunt the careers?of those who do not share their

positivist doctrines. There is a tendency within American political science towards

orthodoxy, with professors from leading departments (like Dominicans) hounding heretics off the tenure track.29 Banishment to a second-class university, or even to

Canada, is not however quite of the same order as the treatment of intellectuals in

post-1968 Czechoslovakia, to which we are invited to compare their situation; the

victims of positivist hegemony do not risk arrest, may even continue to teach, to

publish and to travel.30 And it would be hard to argue that any comparable ortho

doxy stunts the careers of promising academics in Britain, or elsewhere in Western

Europe.

The failure of the Weimar Republic to establish its legitimacy owed something to

the irresponsibility of intellectuals of the right and left, preferring the private certainties of their ideological schools to critical engagement with the difficult

compromises of democratic politics. The Frankfurt School of Adorno and Marcuse were Salonbolschewisten, 'relentless in their hostility towards the capitalist system' while 'they never abandoned the lifestyle of the haute bourgeoisie'?x The followers of

Nietzsche on the right and those of Marx on the left both worked to denigrate the

limited achievements and the political compromises of Weimar, encouraging their

students to adopt their own radically critical positions and so contribute to

undermining the republic. Karl Mannheim, who had attempted in Ideology and

Utopia to build on Weber's conditional and contingent sociology of knowledge, was

among the first professors dismissed when the Nazis came to power. Intellectuals

who live within relatively open civil societies have a responsibility to the society within which they live: to act themselves as constructive critics, and to encourage

27 Chomsky, Ngugi wa Thiong'o and Edward Said represent for Stephen Chan 'the three staunchest and

most eloquent statements ... of the intellectual's role' (Girard et al., Theory and Practice in Foreign

Policy-making, p. 32). Dissidence and resistance are common self-referential terms in the writings of

Richard Ashley, R. B. J. Walker and others; see for example the special issue of International Studies

Quarterly, 34:3 (Sept. 1990): 'Speaking the language of exile: dissidence in international studies'. 28

Weber, 'Science as a Vocation', p. 153. 29 Both James der Derian and Yuen Foong Khong made this point in Oxford seminars in 1994-5. 30 The origins of the Central European University lie in the 'underground university' through which

academics from democratic countries came into 1980s Prague to lecture to dissident intellectuals, at

some real personal risk. Those to whom they lectured were denied any links with the universities of

their own country; most had been pushed into manual jobs (Vaclav Havel, for example, worked in a

flour mill). Bill Newton Smith, of Oxford's Philosophy Faculty, was the first of several of these

unofficial visiting teachers to be arrested in mid-lecture, interrogated through the night, and deported. The Czech philosopher Jan Patochka, one of the founders of Charter 77, collapsed and died after a

24-hour police interrogation in 1978; Jitka Silhanova tells me that on an earlier occasion she passed a

long evening locked in a police cell with him and others, which he converted into a philosophical seminar.

31 Martin Jay, The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School (Boston, 1973), p. 36;

quoted in Dahrendorf, LSE, p. 292.

Truth and power 309

their students to contribute to the strengthening of civil society rather than to

undermine it.32

Post-positivism and pre-positivism

Too much of the current debate on International Relations theory and practice is

ahistorical, fixed on the American traumas of the 1960s and on the perceived

betrayal of academic truth under the pressures of Vietnam by positivists and

Realists. Post-positivists pay little attention to pre-positivists?the generation before Kenneth Waltz (the archetypical Realist on whom postmodernists and critical

theorists concentrate their main attack)?when considering the historical contin

gency in which their predecessors developed their interpretations of global events

and global morality. Theoretical debate on the potentialities of global politics post Cold War needs to refer back to international relations before the cold war. World

politics did not begin in 1945.

Several of the contributions to International Relations Theory Today present the

reader with a caricature of Realism and of the experience of the Second World War,

presenting Realism as a doctrine of Cold War dominance which 'was well sponsored and discounted ethics'.33 Yet Realism as an approach developed well before the Cold

War, as a response to the collapse of the interwar international system; most of its

early proponents were explicitly concerned with the ethical issues at stake. The first

seminar that I attended as a new graduate student in an American university in 1962 was a painfully sober debate about moral choices in nuclear deterrence between

Hans Morgenthau and Hans Bethe, drawing on their experience of the hard

dilemmas of 1930s world politics and of World War Two?both arguing in the

heavily accented English which they had retained from their Central European

upbringing.34 The International Relations scholars of that generation?those who shaped the

Anglo-American discipline?were predominantly Europeans, many of them Jewish, who had come to a disillusioned Realism from confronting the irrationalism and

historicism of Fascism, Nazism and Leninism.35 For them the Enlightenment was

32 Noam Chomsky appears unable to accept this. 'Intellectuals', he writes, 'are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions in terms of their causes and motives and often hidden intentions .. . For a privileged minority, Western democracy provides the leisure, the facilities and the

training to seek the truth that lies hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation' (Chomsky, 'The Responsibility of Intellectuals', in Vasquez (ed.), Classics of International Relations,

p. 59). His unforgiving view is that the intellectual should remain mercilessly against those in power,

regardless of what form of government he lives under. Ernest Gellner, with rather more direct (and bitter) experience of alternative forms of government than Chomsky, insists that the open civil societies which the 'Western' democratic tradition has evolved are qualitatively superior to their

alternatives, and as such deserve a greater degree of intellectual critical support. 'They appear capable of maintaining social order with less violence and oppression, with less deprivation and inequality, than any other large and complex society in history.' Gellner, Relativism and the Social Sciences

(Cambridge, 1985), p. 64. 33

Booth, 'Dare not to Know', p. 332. 34 Hans Bethe was then professor of nuclear physics at Cornell, and had earlier been one of the leading

figures in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. 35 Karl Deutsch for example, dismissed without qualification as a behaviouralist by John A. Vasquez in

Booth and Smith (eds.), International Relations Theory Today, was a German-speaking student in

Prague in 1938 who chose the Czechoslovak cause against the Sudeten Germans, and was then forced

into exile. His lifelong preoccupation with nationalism, communication and the bases of political community stemmed from his own painful personal experiences.

310 William Wallace

not a 'project', but the necessary foundation for an open and stable world. The

suggestion that the Holocaust was a 'manifestation ... of "reason" and "ration

ality" ', or that the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima 'represents the culminating

point of traditional rationality about the games nations play' would have been

greeted by these with the deepest moral contempt.36 They came from a generation of

intellectuals which had suffered far more than the denial of tenure, and who had

struggled with moral dilemmas over justifiable force and necessary intervention far

more fundamental than those which Baudrillard lightly dismissed with reference to

the 1991 Gulf War. To elevate Nietzsche into a prophet of postmodernism, an

intellectual hero for a self-indulgent New Left, while attributing the Holocaust to

those who clung to reason against Nietzsche's anti-rational romanticism, is to deny the fraught context of interwar international politics and the ethical dilemmas which

policy-makers and intellectuals alike in the Western democracies then faced.

If the global politics of the post-Cold War era prove to be as transcendent and

emancipating as our 'utopian realists' promise, then this mispresentation of the pre Cold War era may matter little. The optimism, the neo-Idealism of Booth's vision of

the future, in which 'something profound in world affairs is surely under way' and

'virulent ... nationalism is in decline', is striking?as striking as the old Idealism

with which our discipline began in the aftermath of the First World War. One

should however recall that the Christian pessimism of Martin Wight, Reinhold

Niebuhr and other deeply moral early Realists was a reaction to disappointed idealism and to the failure of the cosmopolitan values they too had preached to

triumph over nationalist reassertion. In a world now transformed by economic

development, environmental concerns and global communications the dangers of a

collapse into irrational disorder are?we may hope?much diminished; but only the

most naive Idealist would assert that such dangers no longer exist.

Both Richard Ashley and Rob Walker are aware of the prehistory of the

sociology of knowledge, and of the contributions which Weber and Durkheim, Mannheim and Popper made to that earlier debate.37 Many of their followers,

however, appear to assume that the simple rationalities of positivism were ques tioned for the first time in the 1970s and 1980s, when 'postmodernists began asking

questions about language, contextuality, the foundations of knowledge ... [and] critical theorists started to ask questions about the ideological basis of knowledge'.38 Such questions are not new; they are intrinsic to social science, and as old as social

science. They were carried through from its Central European foundations to con

temporary debates on the philosophy of social science by Thomas Kuhn, Ernest

Gellner, and others, though briefly smothered in 1960s North America by the

peculiarly American scientistic faith in unconditional rationality. A less sectarian

36 The quotations are from Steve Smith and Ken Booth in Booth and Smith (eds.), International

Relations Theory Today, pp. 2, 331. The vigour with which Ernest Gellner (himself Jewish, an exile in

Britain most of his life first from the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia and then from the Soviet

regime which he found closing in on his return to Prague at the end of World War II) attacked Oxford

linguistic philosophy, unthinking positivism, relativism and postmodernism in successive books

reflected his 'epistemological, sociological and moral commitment to empiricism' (J. Agassi and I. C.

Jarvie, editorial preface to Gellner's Relativism, p. vii). 37 See for example Ashley's essay, 'The Poverty of Neorealism', in Robert O. Keohane (ed.), Neorealism

and its Critics (New York, 1986), and chs. 3-5 of R. B. J. Walker, Inside/outside: International Relations

as Political Theory (Cambridge, 1993). 38

Booth, 'Dare not to Know', p. 338; emphases added.

Tru th and power 311

approach to their own epistemological and ontological insights, a greater degree of

awareness of the historical contingency of their own approach to knowledge, and

above all a greater knowledge of the history and ideological debates of the pre-Cold War era, might moderate the self-righteousness with which the neo-Idealists

approach the continuing debate over theoretical perspectives and over the appro

priate relationship between theory and practice.

Scholarship and scholasticism

Scholarship, to quote the motto of the London School of Economics, is to seek 'to

know the causes of things': to investigate some aspects of the chaotic universe of

evidence, events and experience, and to impose a degree of explanatory order on

them.39 Scholarship necessarily involves conceptualization, categorization, and

explanation, and assumes transmission of the knowledge gained to others.

Scholarship hardens into ideology or dogma when the contingent basis for explana tion?the necessary doubt which should accompany all intellectual discovery?is

forgotten. It deteriorates into scholasticism when its practitioners shift from

attempts to address common questions from different perspectives to competition

among different 'schools'; in which each multiplies definitions and explanations,

develops its own deliberately obscure terminology, and concentrates much of its

efforts on attacking the methods and terminology of competing groups. The Oxford

English Dictionary defines scholasticism as 'pedantic, needlessly subtle'; it developed out of the overpreoccupation of medieval university teachers with disputes with

each other rather than with engagement with the problems of the world beyond their

monastic or university walls.

There is a danger that our discipline could follow the path that sociology took,

becoming too self-preoccupied, too determined to leave its origins in applied research and policy-related work behind, to take refuge in increasing abstractions, theories and met a-theories: to move from scholarship to scholasticism.40 Academic

sociology, it should be noted, first denied its policy audience and then lost a good

part of its student audience. The preoccupation with word games among theorists of

International Relations, the element of flippancy (or fun, as some followers of

Foucault and Baudrillard would put it) in postmodernist writing, the celebration of

theory at the expense of empirical work, all suggest that there are many who are

tempted to go down the same road.

From this perspective European Foreign Policy: The EC and Changing Perspectives in Europe?from its title the most empirical of the volumes under review?appears as the most scholastic, the most detached from the world outside the discipline. 'Our

main concern', Steve Smith declares in the introduction, 'is to use the case-study of

the vast changes sweeping Europe to inform our analysis of the state of FPA

39 The motto of Oxford University?Dominus illuminatio mea?is wonderfully ambiguous in this respect:

open to translation either as 'the Lord is my enlightenment' or as 'the tutor tells me what to think'. 40 Ernest Gellner, in Postmodernism, Reason and Religion (London, 1992), pp. 22-71, provides an account

of the scholastic disputes which enveloped sociology and social anthropology in the 1970s and 1980s.

312 William Wallace

[foreign policy analysis]. If, along the way, we can say something about the nature of

those changes, that will be a bonus.' (p. 19) Marysia Zalewski is more radical.

Starting 'from a quasi post-modern stance', she sweeps past 'the twin revolutions

that have given rise to the so-called "new Europe"' to address 'my supposed

empirical area: women.' (pp. 223^) Attacking those who 'strive towards simplifica tion and categorization ... to produce coherent, all-purpose theories', she quotes

with approval Sandra Harding's dictum that

coherent theories in an incoherent world are either silly and uninteresting or oppressive and

problematic, depending on the degree of hegemony they manage to achieve. Coherent

theories in an apparently coherent world are even more dangerous, for the world is always more complex than such unfortunately hegemonic theories can grasp.41

The world and all that there is in it are unavoidably too complex for the human

mind fully to grasp. The question is whether the role of the scholar is to try to

understand (which unavoidably involves simplification and categorization) and to

help others to understand, or whether she should deny that duty and leave herself, her students and readers in confusion. It's easy to sympathize with Ole Waever's

protesting rejoinder.

With the general assault on international relations which has been carried out through the 1980s by various types of reflectivists, post-modernists, post-structuralists, feminists and

critical theorists, it would seem an almost too easy job to drag down FPA as well.42

American exceptionalism, American hegemony

As odd a feature of this study of West European responses to the collapse of socia

list regimes in Central and Eastern Europe is the audience it seeks to address: the

American academic International Relations community. 'The obvious danger' of

targeting such a limited audience, of accepting the dominance of their theoretical

approaches, Steve Smith admits, 'is that US FPA may not be relevant to the

European setting'. 'Yet the problem remains that, for European FPA specialists, their work will only be accepted as relevant if it addresses the concerns and

approaches of the US research community', (pp. 10-11) Relevant to whom, and for

what? To the wider audience in our own countries, to our students, to our policy elites?or to the small world of academic conferences, centred around ten US

universities and five US journals, within which an increasingly self-absorbed profes sional academic community pursues its scholastic careers?

If European FPA is to be taken seriously in the international FPA community, then this means referring to US approaches

. . . the sheer size of the US academic community means

that it is difficult to swim against the tide . . . [even though] the rise and fall of various FPA

approaches have more to do with the changing agenda facing the US than with any theoretical deficiencies, (pp. 13-14)

41 In Carlsnaes and Smith (eds.), European Foreign Policy, p. 224; quoting Sandra Harding, The Science

Question in Feminism (Milton Keynes, 1986), p. 164. 42 Ole Waever, 'Resisting the Temptation of Post FP analysis', ch. 13 in Carlsnaes and Smith (eds.),

European Foreign Policy, p. 238.

Tr u th and power 313

To different degrees all social sciences face the problem of coping with American

intellectual hegemony: the sheer weight of numbers, the entrenched influence of

American ideas within international institutions such as the IMF and the World

Bank, the continuing financial importance of the major US foundations in under

writing research and so in setting the intellectual agenda. A central problem for

European scholars when faced with this preponderance is, as Susan Strange robustly

puts it in International Relations Theory Today, that 'academic writing by the great

majority of Americans is blissfully and habitually deaf and blind to the ideas and

perceptions of the outside world'.43 The USA is an exceptional society, both in terms of its size, its geopolitical and

economic insulation from the outside world, and in terms of its intellectual and

ideological history and self-image.44 The particular and painful experiences of

American political science and International Relations during the Vietnam War?

which nearly tore the discipline apart?had no direct parallel in any other democ

racy.45 'The peculiarly American quest for shortcuts to understanding the complex . . . the quest for scientific precision and certainty where it doesn't belong, the view

of the world as if only the superpowers mattered . . . the complacent parochialism of so many' all represent deformations apparent to acute observers within American

universities.46 The current trend away from area studies, from regional and linguistic

expertise, which is evident in American university patterns of hiring and promotions,

implies that European scholars will have to grapple with an increasingly parochial academic community within the United States.

Given that the number of social scientists outside the USA, in Asia as well as in

Europe, continues to increase, it should no longer be necessary for British and other

European scholars to be so unselfconfident about our own theoretical development, so derivative of American theorizing and intellectual fashions. The situation of the

United States, a half-continent immensely rich in natural resources and surrounded

by oceans, 5 per cent of the world's population accounting for 23 per cent of the

world's income (conventionally measured?and 22 per cent of the world's carbon

dioxide emissions), is exceptional. Approaches to world politics based upon American perspectives are therefore likely to be only loosely applicable to the situation in which the world's other 190 states and five billion people find themselves.

It seems a sad reflection of our continuing intellectual dependence that the new

European Journal of International Relations should have announced itself, in

the autumn of 1994, with an international advisory board almost half of whose

members were drawn from North American universities, and with the promise of

43 Susan Strange, 'Political Economy and International Relations', ch. 7 in Booth and Smith (eds.), International Relations Theory Today, p. 165; citing in her support K. J. Holsti, The Dividing

Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory (Boston, MA, 1985) and Richard Higgott, 'Towards a Non-hegemonic IPE', in Craig Murphy and Roger Tooze (eds.), The New International

Political Economy (Boulder, CO, 1991). 44 Martin Trow, 'American Higher Education: "Exceptional", or just Different?', ch. 6 in Byron E. Shafer

(ed.), Is America Different? A New Look at American Exceptionalism (Oxford, 1991). 45 Theodore Lowi, 'The Politics of Higher Education: Political Science as a Case Study', in George J.

Graham and George W. Carey (eds.), The Postbehavioral Era: Perspectives on Political Science (New York, 1972), pp. 11-36; Raymond Seidelman and Edward Harpham (eds.), Discipline and History (East

Lansing, MI, 1995). 46

Stanley Hoffmann, 'A Retrospective on World Polities', ch. 1 in Ideas and Ideals: Essays on Politics in

Honor of Stanley Hoffmann, ed. Linda B. Miller and Michael Joseph Smith (Boulder, CO, 1993) pp. 15-16.

314 William Wallace

early articles by leading American academics to persuade us to subscribe. The

recovery of German intellectual life (and the strength of social sciences elsewhere in

northern Europe, from the Netherlands to Finland) should encourage academics in

Britain to look across the Channel, rather than take our lead from the intellectual

grandchildren of the great wave of European emigres who laid the foundations of

post-1945 American social science. Most of the current American academic

profession have never understood the historical or geopolitical European context

within which their predecessors had developed their approaches.

Testing theory: the necessity of empirical work

The interaction between theoretical and empirical work, between concepts and

evidence, is at the heart of social science. Barefoot empiricists at one end, and philo

sophers of social science at the other, mark the outer limits of a continuum along which different groups of researchers are clustered: most?in a flourishing

discipline?towards the centre. Useful theories only develop out of repeated and

careful confrontation with evidence, carefully collected and assembled to confirm? or undermine?dominant paradigms. Without empirical research, theory becomes

increasingly abstract and arid. A discipline which dismisses the importance of

applied research?because it is regarded as grossly inferior to theoretical work, because it costs more time and money, because it often requires knowledge of

foreign languages in this essentially Anglo-Saxon discipline, because it involves com

promising contacts with politicians, governments, policy-makers?will find that it

has closed itself up within its own scholastic community.

More, and more detailed, empirical research should be one of our first priorities,

guided by theoretical assumptions but intended to inform?and so modify? theoretical assumptions. It is difficult to conduct an inter-paradigm debate, after all, unless empirical studies are available to test one paradigm against another. Here

again I contend that our discipline is in danger of becoming unbalanced, pre

occupied with theory for its own sake rather than as a means to explanation, and

with a remarkable neglect of detailed study of developments within our own region and of their relevance to theory. The agenda of the 1994 BISA Conference included

eight panels on theory, with eighteen papers. There were no papers on British foreign

policy, and only two papers (out of 123) in different panels on the interaction

between Britain's society or economy and the wider regional or global system. Apart from four papers on the crisis in Yugoslavia, there was only one paper (on The role

of women in Poland, 1979-81') on the transformation of Central and Eastern

Europe over the previous fifteen years?from which a large number of lessons

must in time be drawn for our understanding of regional and global politics. This

snapshot suggests a discipline in which prestige and reputation rest more upon theoretical disputation than upon careful empirical study.

This neglect of the European region and of conceptual approaches to that

region?with the creditable exception of Fred Halliday's Rethinking International

Relations, which revolves around approaches to the Cold War as a phenomenon, its

end and its aftermath?is remarkable, given that the discipline originally developed out of intellectual preoccupation with the European international system. The

Tr u th and power 315

region is almost entirely absent from International Relations Theory Today. Forty five years of debate on state and sovereignty, on integration and interdependence in

Western Europe, from Ernst Haas to Alan Milward, is left out?though the

American John Mearsheimer, whose ignorance of contemporary European

developments shines out from his neo-Realist writings, is granted extended treatment

in successive chapters. Susan Strange is the only contributor who refers to Mitrany and Haas, those earlier Idealists equipped with a clear research agenda; Fred

Halliday the only one (of sixteen contributors in 350 pages) who mentions the

European Community. There are optimistic references in several chapters to pros

pects for cosmopolitan democracy, without any comparison with the sobering

experience (and the early, disappointed, idealist hopes) represented by the one

operating example of a supranational democratic assembly in the world: the

European Parliament. Marysia Zalewski and Cynthia Enloe address 'Questions of

identity in international relations' with scarcely a reference to the national dimension

of identity: as if there were no resurgence of claims to sovereignty on the basis of

dominant ethnic identities across the former socialist Eurasian world, or as if such a

resurgence had little significance for the study of international relations.

?A discipline's silences', Steve Smith remarks in his introduction, 'are often its most significant feature' (p. 2). In three years of membership of the Research Grants

Board of the UK Economic and Social Research Council, the most significant silence I observed was the absence of proposals from International Relations

scholars to study the transformation of regional politics across Europe, even as the

ESRC awarded successive grants to students of comparative politics, to sociologists and economists, to conduct research in this field. But there are other significant silences in the discipline. Jean Bethke Elshtain remarks on the failure of students of

transnational social movements to tackle the old-established, and continuing,

importance of churches and other religious movements; to which one might add

the importance of clandestine and criminal groups and 'Mafias'.47 Halliday (in

Rethinking International Relations, pp. 103-7) remarks on the absence of historical

perspective in much of the transnational/cosmopolitan literature, neglecting the

existence of strong transnational movements?freemasons, anabaptists, socialist and anarchist groups?in the international system of the past three centuries.

Those who are acutely preoccupied with 'the main meta-theoretical issue facing international relations theory today', which they define as 'the fundamental divide . . . between those theories that seek to offer explanatory accounts of international

relations and those that see theory as constitutive of that reality', may object that

such an emphasis on empirical research begs the question of the framework within

which such research may be conducted.48 Without empirical work, however, the

47 Jean Bethke Elshtain, 'International Politics and Political Theory', in Booth and Smith (eds.), International Relations Theory Today, p. 269: 'Political and international relations theorists consistently understate the power of religious conviction and its role as a defining, shaping, and constitutive force in

world affairs ... The Church is the oldest continuing player in diplomatic life in the West but you would never know this from contemporary accounts of the sort taught to students of international politics.'

Interestingly enough, however, Rob Walker (in 'International Relations and the Concept of the

Political', ibid. p. 312) uses religious terminology to describe the growth of social movements as a force in world politics. 'To speak of a movement now, even a movement firmly rooted in the secular

necessities of capitalist modernity, is to do so in languages and concepts that have not quite lost their

theological resonance.' 48 Steve Smith, 'The Self-images of a Discipline', in Booth and Smith (eds.), International Relations

Theory Today, p. 27.

316 William Wallace

discipline will lose touch with the phenomena it sets out to interpret, and become little more than a branch of literary enquiry or linguistic philosophy.49 Uncertain

theory and inadequate evidence are?to repeat?intrinsic to social science; John

Vasquez's charge that 'Realists have always had a problem with evidence' does not

explain how post-positivists can avoid such problems themselves.50 We can only cling to Karl Popper's sceptical approach, and creep forward while making our assump tions and the basis for the evidence we have collected as transparent as possible, for others to challenge.

What we should not do is allow academics to use theoretical uncertainty as an excuse for abandoning empirical work. 'Many in the field take glee' in the post

positivist 'crisis ... [in] the scientific study of world polities', Vasquez admits, 'for

they believe it sounds the death knell for a form of analysis they never liked and which they find boring and difficult'.51 Meta-theory and intertextual analysis may be more fun than hard case-study work or the collection and analysis of evidence, and much easier to write about without leaving the ivory tower or monastery. That way, however, lies scholasticism, the multiplication of fine distinctions without new

knowledge.52 We now find ourselves faced not only with the immense laboratory of the post

socialist world as a field for study, but also with the challenge of educating an

emerging intellectual class from those countries: eager to develop new departments of International Relations in their universities, to train their (often new) diplomatic services, the officials who will staff the regional international institutions they hope to join and the journalists who will comment on the domestic implications of

international developments. What should we teach them? What are the core themes

and issues of the discipline to which we should introduce them first, 'the range of

debates engaging the discipline' on which we should focus their attention?53 These are not trivial questions: we may hope through such education to contribute?at least at the margin?to the stability of a historically unstable region, even to the evolution of democratic states and open societies within that region.

Western economists rushed east after 1989 to offer simplistic models of transition to open markets, often disregarding both local circumstances and the particularities of the regional environment. Western International Relations scholars have been less

49 'It is not an accident that postmodernism has had its most profound impact on literary theory. Literary theorists, after all, deal with fiction, so for them empirical truth is never really a concern. ..' John A. Vasquez, 'The Post-Positivist Debate: Reconstructing Scientific Enquiry and International

Relations Theory after Enlightenment's Fall', in Booth and Smith (eds.), International Relations

Theory Today, p. 224. 50

Ibid., p. 235. The books under review suggest that post-positivists are at least as anecdotal in their use

of evidence as the Realists they attack. The assertion by Marysia Zalewski and Cythia Enloe that 'We can drink Coke, eat sushi and watch Neighbours and be in practically any country in the world' (p. 302) suggests a very limited knowledge of conditions outside the democratic capitalist countries of the

OECD. 51

Ibid., p. 234. 52 Behaviouralists at their most rigorous were almost as purist and exclusive in their approach to what

could be studied. Many behaviouralists came to attach more importance to their methodology than to

the significance of the questions they studied; the highly behavioural Political Science Department of the European University Institute in Florence refused to teach or research either on European

integration or on international relations for most of its first decade, in defiance of the purposes for

which it was established and of its dependence on the EC for its funding, as not compatible with a

'scientific' approach. IR scholars in their turn should avoid this professional deformation, of putting fascination with methodology before the significance of the issues to be addressed.

53 Keith Webb, in Girard et al., Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making, p. 92.

Truth and power 317

often in demand, although many of us have welcomed students from these countries

into courses in our home universities.54 In the Central European University,

Budapest, we have attempted to construct an IR syllabus which will make sense to

graduate students from twenty-five countries across Central and Eastern Europe and

Eurasia for whom war, ethnic conflict, exploitation of alleged foreign threats to con

solidate authoritarian government, military forces not subject to civilian control,

governmental incapacity, economic dependence, forced migration, are real and

immediate issues?not opportunities for word plays or of interest only for their

contribution to the construction and refinement of theory. There is sadly little in the

recent Anglo-American theoretical literature that is useful, and too much which

either ignores or mocks the profound significance?for the discipline as well as for

the international system?of the transformation of European and global order

which has been under way since the late 1980s. Explanation, conceptualization,

categorization, simplification?supported by empirical studies?are essential

elements in any such teaching enterprise. To deny that would be to deny that

International Relations has more to offer such students from such countries than the

traditional intellectual disciplines of classics or mathematics.55

Striking the balance: the case for semi-detachment

Teachers of International Relations however insist that our discipline does have more to offer students?and (for most) also policy-makers?than classics. Keith

Webb defines the discipline of International Relations as one 'which by its nature

deals with some of the most pressing problems facing humanity', a profession 'which many scholars enter ... with a desire to do something about them'.56 There is,

he argues, 'a particular role for the social scientist, which is of relative dis

engagement from the policy process': a degree of detachment from immediate events

which 'does not mean normative detachment, nor imply some kind of distanced

neutrality or dispassion regarding issues.' A dispassionate approach is for him 'the

hallmark of scholarship' even when the scholar is emotionally engaged in the issues

at stake.57

Semi-detachment, relative disengagement, rather than the extremes of co-option into the policy-making arena and its current assumptions or the passionate detach

ment which postmodernists affect?proclaiming that they wish to transform the

54 One exceptional two-day seminar (in which I participated) was provided by the Harvard University

Kennedy School to the newly independent government of the Ukraine, in late December 1991. It was

attended by a dozen ministers, including the ministers of foreign affairs and economics, a number of

military and civilian officials, and members of the Ukrainian Parliament. Many had never been

abroad; MPs from Rukh had never previously met anyone from outside the USSR. They knew almost

nothing of the basic rules and assumptions of the international society of which they claimed

membership; the foreign minister's opening statement declared the 'basic aims' of Ukrainian foreign

policy to be full membership of NATO and the EC by the end of 1993. 55 The rationale for classics as a focus for higher education is that it trains students in linguistic precision,

logic, and the careful interpretation of uncertain evidence: skills which can then be applied to a range of contemporary problems. The teaching of international relations to future practitioners should

attempt to provide training in similar skills, related more directly to contemporary problems. 56 'Academics and Practitioners: Power, Knowledge and Role', in Girard et al., Theory and Practice in

Foreign Policy-making, p. 13. 57

Ibid., pp. 13,22.

318 William Wallace

world while avoiding contact with those who exert significant influence over the

world?offers a precarious balance. Semi-detachment because, like other social

scientists', our theories and concepts, when they are accepted by significant audiences in terms of size or influence, help to shape the world which we study:

Every political judgement helps to modify the facts on which it is passed. Political thought is itself a form of political action. Political science is the science not only of what is, but of

what ought to be.58

The choice is not between an uncritical commitment to power or an unvarnished

commitment to truth; it would be to abandon our intellectual responsibilities either

to turn our university departments into enclosed communities or to convert them

into contract research consultancies for whatever government is in power. The exact

point of balance chosen between detachment and engagement will necessarily

depend on personal judgement, within the context of individual assessments of the

nature of the polity?its openness to outside criticism, or its resistance to (even resentment of) advice and criticism?and the importance of the issues at stake.

Christopher Hill and Pamela Beshoff warn that 'scholarship is at risk from too

enthusiastic commitment to the policy debate', but nevertheless accept that cautious

engagement is an academic responsibility.59 John Vincent, in a paper given to an

LSE seminar before his death (now published in Two Worlds of International

Relations), leans in the opposite direction in his insistence that

Theory and policy are two sides of the same coin in that they both represent a priori outlines which can then be tested empirically, in the first place against something called 'truth' and in the second against political practice

... Theory cannot be an intellectual exercise divorced

from the requirement ultimately to deliver a position on policy. Our theories have to address

painful dilemmas and, if heard in the world of politics, they can have painful consequences.60

Before the professionalization of the discipline within the past generation, it

should be noted, most theorists of international relations combined reflection with

practice, or with advice to practitioners, at different points in their careers. John

Locke was one of the first members of the English Board of Trade. David Mitrany

practised his functionalist principles as a director of Unilever, before wartime

secondment to the Foreign Office provided the opportunity to participate in design

ing the network of UN functional agencies. A high proportion of those who first

developed the academic discipline of International Relations in Britain had partici

pated, as junior officials or attach?s, in the Versailles conference of 1919; their

E. H. Carr, The Twenty Years' Crisis (1946, reprinted New York, 1964) p. 5. This comment by one of

the founders of the Realist tradition illustrates how intrinsic to pre-positivist social sciences was

awareness of the interaction between ideas and action, between conceptualization and ideological

preference. 'The first step to the understanding of men is the bringing to consciousness of the model or models that dominate and penetrate their thought and action. Like all attempts to make men aware

of the categories in which they think, it is a difficult and sometimes painful activity, likely to produce

deeply disquieting results.' Isaiah Berlin, 'Does Political Theory still Exist?', in Peter Laslett and W. G.

Runciman (eds.), Philosophy, Politics and Society (2nd series, Oxford, 1962), p. 19. Berlin was of course

another representative of that great Central European intellectual diaspora who devoted their lives to

studying those questions of fact and value, perception and reality, which postmodernists imagine themselves to have newly discovered.

'The Two Worlds: Natural Partnership or Necessary Distance?', in Hill and Beshoff (eds.), Two

Worlds, p. 212.

John Vincent, 'The Place of Theory in the Practice of Human Rights', ibid., pp. 29-30.

Truth and power 319

successors of the post-1945 generation almost without exception had direct ex

perience of war or government service. E. H. Carr had served in the Foreign Office

and then worked for The Times while holding the Woodrow Wilson chair at

Aberystwyth. Many of the American theorists on whose writings so many of our

theoretical controversies on this side of the Atlantic depend have spent time in

government in Washington. There are of course risks and dangers in such a high degree of engagement: from

co-option into the political game to partisan and personal attack, to ruined careers

and lives.61 But there are advantages as well, in terms of the perspective gained on

which to reflect on the return to the intellectual world. If we were to exclude from

our discourse (and our reading lists) all those contaminated by direct involvement

with the world of policy, we would emasculate our discipline. Chapters in Theory and Practice in Foreign Policy-making on Germany, France, the Netherlands,

Sweden, Russia, the USA and Austria illustrate the interaction between different

patterns of politics and government, distinctive political and intellectual traditions, and the particular opportunities and dilemmas faced by their academic International

Relations communities. A degree of tension is evident in every country studied:

between government as funder and universities (and policy institutes) as recipients, between academic desires for prestige and influence and official concerns for

immediate and often confidential advice.

The chapter on Britain, based on a survey of BISA members in November 1991,

presents a picture 'of a profession desiring, in the main, to participate in the policy

making process and believing, rightly or wrongly, that their contribution to that

process would be significant'.62 But it also indicates that 'many academics feel

excluded from the policy-making process', that academics teaching outside the

south-east of England feel severely disadvantaged, and that some perceive 'the

existence of a "golden triangle" between London, Oxford, and Cambridge'.63 The

image which emerges from this survey is of a profession confused about what

relationship it would like to have with the policy world, ill-informed about the

existing situation, with some of its members excluding themselves from fruitful

exchanges through the fears and suspicions they arouse. The myth of a 'golden

triangle' lingers long after the reality has departed: the last academic seconded to the

Foreign Office came from Birmingham University; her successor is on leave from

Sussex. There is no mention in this chapter of the London policy institutes, whose

role as intermediaries between the two worlds has served in its time Arnold Toynbee and E. H. Carr, Martin Wight and David Mitrany, Alastair Buchan, Susan Strange and John Vincent.64 Senior research staff at the Royal Institute of International

Affairs have recently included secondments from Wolverhampton, Staffordshire,

Warwick, and Birmingham (as well as from the Foreign Office and the Treasury), while junior staff have moved on to a number of other universities. Civil service

training in international and European issues is provided most often by staff from

Loughborough and Exeter.65

61 Seneca, one of the earliest recorded intellectual advisers to government, was 'allowed' by the Emperor to commit suicide.

62 Keith Webb, 'Academics and Professionals: Britain', in Girard et al., Theory and Practice, p. 90.

63 Ibid., pp. 89,91.

64 William Wallace, 'Between Two Worlds: Think Tanks and Foreign Policy', ch. 8 in Hill and Beshoff

(eds.), Two Worlds. 65 This information was drawn from Civil Service College course outlines collected in October 1994.

320 William Wallace

There is no mention either of the contribution some academics (too few) make to

parliamentary committees, to party policy-making and to partisan think-tanks, with

all the distinctive opportunities and risks which these offer. There is room for further

discussion within the discipline on patterns of interchange and access to influence. A

situation in which 'many International Relations experts feel that their expertise should be used more' while feeling excluded from a relatively open policy-making process suggests a degree of misperception and a lack of communication.66 The

absence of the direct path to influence available in the United States, where a sub