Tigers Alive - Pandaassets.panda.org/downloads/tiger_alive_booklet_1.pdf · 4 TIGERS ALIVE WWF and...

Transcript of Tigers Alive - Pandaassets.panda.org/downloads/tiger_alive_booklet_1.pdf · 4 TIGERS ALIVE WWF and...

Tigers AliveTHE WWF TIGER CONSERVATION INITIATIVE

TIGERS ALIVE

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWF

-Canon

1The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

CONTENTS Introduction 2

WWF and Tigers 4

Meeting the Challenge 5

WWF’s Tigers Alive Strategy in Brief 6

The Landscape Approach 7

Core Sites And Potential Core Sites – The Foundation For Recovery 8

Understanding a WWF Tiger Landscape 10

Critical Actions in WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes 12

Eliminating the Illegal Tiger Trade 23

Reducing Demand 25

Securing Tigerlands – Saving Tigers and So Much More 27

Conclusion: Together We Can Save the Tiger 30

© Da

vid Bi

ene / W

WF Ge

rmany

© Ch

ristoph

er Wong

/ WWF

Malay

sia©

James

Kemsey

/ WWF

Malay

sia©

WWF-R

ussia /

D. Ku

chma

© WW

F India

front c

over p

hoto:

© Fra

ncois S

avigny

/ WWF

TIGERS ALIVE2

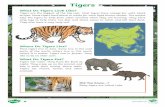

IntroductionAt the turn of the 20th Century, there were an estimated 100,000 tigers living in a remarkably diverse set of habitats – from the Caspian Sea in the far west of Asia to northeast Russia and China, and as far east and south as the island of Bali in Indonesia.

In less than 100 years, however, the wild population is estimated to have fallen to as low as 3,200. Entire sub-species such as the Caspian, Javan and Balinese tigers have gone extinct while the south China tiger may have also disappeared from the wild. The tiger’s once wide distribution has shrunk by 93 percent and in most cases tiger populations are restricted to a few desperate refuges in these last remaining patches of habitat. The future for the tiger could not look bleaker.

© And

y Rous

e / WW

F

3The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

The threats to tigers are well known, and include poaching to feed the voracious demand for tigers and their parts, poaching of their prey, direct killing by communities living amongst tigers to revenge livestock losses or even the loss of human life, and the rapid, extensive destruction of the grasslands and forests where tigers and their prey live. These threats have changed very little in nature, but have intensi!ed in recent years while tiger populations and their habitats have shrunk.

The world’s largest cat and most e"ective land predator, the tiger dominates the forests in which it lives. Since tigers need a constant supply of prey and, consequently, vast areas to maintain robust populations, and o#en pose a threat to local people and their livestock, the struggle for the tiger’s survival in the wild is one of the greatest challenges facing wildlife conservation today.

Nevertheless, even as the tiger is on the verge of extinction throughout most of its range, there is hope.

The last four decades of intensive tiger conservation e"orts have yielded extensive knowledge. We know how to protect, manage and monitor tiger and prey populations and their habitat. We know more about the nature of the trade – why people want to buy tigers and their parts. WWF is using this knowledge to work with our partners and take

action that answers both the challenges of having a will and a way to stop the tiger’s decline. New partnerships have been forged. Government engagement is growing and !nancing options have never been so broad and creative.

In response to the urgency of the crisis and to grasp the opportunities just outlined, WWF has launched a revitalised programme, Tigers Alive. We aim to stop the decline of the wild tiger and help create and support the conditions to double the number of tigers in the wild in the next 12 years.

Together with our partners, WWF is mobilising the full force of its vast network — from the !eld biologists monitoring the tiger and its prey, trainers building the capacity of forest sta", and rangers protecting critical sites for tigers, to the !nancial experts working with donors and governments to create new funding mechanisms for tiger protection, and the policy and advocacy specialists working with decision makers.

The chance to turn the future around for the tiger has come – it may be our last.

Introduction

© And

y Rous

e / WW

F

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWf

-Canon

TIGERS ALIVE4

WWF and Tigers WWF’s Tigers Alive Initiative operates in 12 of the 13 tiger range countries – Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Nepal, Russia, Thailand and Vietnam.

Tiger conservation has been a priority for WWF in these countries for the past decade, and more in some. For example, in India, WWF has been supporting tiger conservation since the 1970s. During this time, we have gained valuable experience, developed expertise, and forged critical partnerships and collaborations with various stakeholders.

TRAFFIC, WWF’s joint programme with IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, specialises in wildlife trade issues, working with external partners on the ground to address poaching and tra!cking issues. With the increase in sophistication in the methods of poaching and illegal trade, it has become clear that we must do more, and "nd new ways to complement tried and tested methods. Raising the bar WWF launched its revitalised tiger programme in 2010, the Year of the Tiger in the Chinese lunar calendar. We intend to support e#orts to stop the decline and double the number of tigers in the wild by the next year of the tiger in 2022.

Many ask if it is possible to raise the population from around 3200 to over 6000 in 12 short years. It is certainly possible, but it will require a profound shi$ in the approaches that have been tried until now, and intensifying and strengthening those that work. To reach

this target in such a short period of time will require all those working on tiger conservation to do things di#erently, better, and more intensively. The key point is that unless we shi$ our e#orts, we will lose tigers from many of the landscapes in which they remain. To lose this iconic species, which has been revered for generations and still symbolises mystery and strength today – the brilliance of nature and biodiversity in our increasingly small world – is a tragedy we cannot a#ord to let happen on our watch. Only an upsurge of e#ort, working at higher levels of intensity, cooperation and accountability, will stop this scenario becoming reality.

WWF refuses to let the tiger slip away. We are dedicated to bringing the tiger back from the brink of extinction and doubling its numbers in the wild.

© Da

vid La

wson

/ WWF

-UK

5The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Meeting the Challenge

WWF is well positioned to meet the challenges and opportunities facing tiger conservation. We have identi!ed six key approaches in our tiger conservation strategy that will help us achieve greater, more sustained impact.

Strengthening ‘what we know works’ We will intensify and strengthen

approaches that we know work. Examples of these are the engagement of local communities living with or close to tigers, and the use and sharing of e"ective tools such as for monitoring law enforcement. We will invest su#cient resources and stay the course in the landscapes we have identi!ed as our focal points.

We will set clear and measurable goals so that we can focus our e"orts where they will have the greatest impact, create measurable and accountable work plans for each aspect of our programme, and target resources to actions critical to achieving our objectives.

Today’s technology allows WWF to be better at measuring and monitoring tigers, their prey and habitat. For example, the increasing use of remote technology, such as camera traps and satellite imagery, helps us make better-informed decisions and monitor where our interventions are having an impact, or where we might need to adapt our strategies.

The real success of our ambitious goal will rely on an e"ective network both within WWF and with external partners. We will improve our capacity and that of our partners where needed and learn from the successful actions of others.

We will strengthen protection of the tiger, its prey and their habitat through building capacity of !eld sta" of forest and wildlife agencies. Collaboration with enforcement agencies responsible for curbing poaching and illegal wildlife trade will also be a critical strategy.

In order to be truly successful, WWF and partners need to ensure tiger conservation is regarded as a priority at the highest levels of government and that senior o#cials are accountable for the recovery of the tiger. We have already begun this, with our role at all three levels – local, national and international – and this work has expanded as of late.

© De

s Syaf

rizal /

WWF In

donesi

a

TIGERS ALIVE6WWF’s Tigers Alive Strategy in Brief The overarching goal of our Tigers Alive strategy is to double the number of wild tigers by 2022.

We have a bold plan to galvanise political will and take action to double the number of wild tigers in the next 12 years, focusing on 12 landscapes that some of the world’s top tiger experts

chances of increasing the world’s tiger populations across the species’ range.

The strategy has three objectives designed to help us reach the overarching goal.

Objective 1 – Protecting tigers, their prey and habitat

We will ensure that by 2022, the 12 WWF

managed through better enforcement, sound monitoring and adequate

Objective 2 – Eliminating the illegal tiger trade

tiger parts and derivatives to negligible levels by 2022, so that this illegal trade no longer threatens the survival of wild tiger populations.

Objective 3 – Increasing political will, commitment and funding

We will secure and maintain strong political and institutional support, as

conservation from now until 2022 and beyond.

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050

Year

Tigers Extirpated from Bali: 1940s

Tiger Population

Tigers Extirpated from S. China: 1990s

Tigers Extirpated from Java: 1980s

Tigers Extirpated from Central Asia: 1970s Continued decline if threats

are not adequately addressed

2020 Goal: Tiger Population Doubles

to at least 6,000

??

Tiger Population Trend

© Ed

win Gi

esbers

/ WWF

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

40,000

45,000

Estim

ated

Tig

er P

opul

atio

n

7The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

WWF’s Tigers Alive Strategy in Brief

Tigers are “landscape” species – they need large areas with diverse habitats, free from human disturbance and rich in prey. In all the landscapes they live, tigers play a signi!cant role in the structure and function of the ecosystem on which both humans and wildlife rely. Once covering vast areas, the tiger’s range has become fragmented. Tigers now live in isolated patches scattered throughout most of their previous range. The larger, most important areas of remaining habitat have been listed, described and prioritised as Tiger Conservation Landscapes (TCLs). These landscapes house some of the richest biodiversity, the poorest human populations, and the most critical watersheds and carbon repositories on Earth. Tiger conservation here will have immeasurable bene!ts for overall biodiversity conservation, and will help meet many national and international obligations, such as those under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Millennium Development Goals.

The 12 WWF Priority Tiger LandscapesWWF has identi!ed 12 landscapes where we will focus our attention. 1. Amur-Heilong – China and Russia2. Kaziranga–Karbi Anglong – India3. Satpuda-Maikal – India4. Western Ghats-Nilgiris – India 5. Greater Manas – Bhutan and India 6. Sundarbans – Bangladesh and India7. Terai Arc – India and Nepal8. Forests of the Lower Mekong –

Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam9. Dawna-Tennaserim – Myanmar and

Thailand10. Banjaran Titiwangsa – Malaysia11. Central Sumatra – Indonesia 12. Southern Sumatra – Indonesia

It is our long-term aim to restore tigers within these landscapes, where ensuring their security and well-being is feasible and where they will not cause unavoidable con"ict with humans. Focusing on these sites supports our tiger conservation objectives, and also those of other WWF "agship species, such as rhinos and elephants, as well as other species we work on, including the snow leopard, Amur leopard, mainland clouded leopard, Sunda clouded leopard, red panda, Eld’s deer, banteng and saola.

We will apply our landscape approach to tiger conservation in all 12 landscapes. This is a holistic, multi-disciplinary and transboundary approach, that is also direct, strategic and focused. It is based on a clear plan aimed to increase tiger numbers in the most e#cient and e$ective manner, while taking into account the need for human development. Working in partnership with stakeholders, we will manage the landscapes through strategic interventions according to a system of land-use zones designed to meet the needs of both tigers and the people living and working in these areas. Please see the Tigers Alive Landscape map on pages 16 and 17.

The Landscape Approach

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWF

-Canon

© Jak

ob Jes

persen

TIGERS ALIVE8

Tigers need large areas to maintain robust groups of interactive local populations (referred to as metapopulations). This is why WWF works at the landscape level. However, within the landscapes, there are areas that are more suitable for tigers than others in that they have high prey densities and other favourable breeding conditions. WWF calls these areas “Core Tiger Areas” (CTAs) and they are similar to what others have de!ned as core breeding areas and source sites.

These core areas, with at least 25 breeding tigers each, are the beating hearts of the WWF priority tiger landscapes. They produce tigers that disperse and populate the rest of the landscape. As the foundation for all successful tiger conservation e"orts in the landscape, they require the strictest level of protection.

WWF regards these areas as the highest priority for investment in terms of protection and monitoring. We are

focusing e"orts on several Core Tiger Areas that have the highest densities and largest numbers of tigers in the world. They include Kaziranga, Corbett and Kanha Tiger Reserves, Nepal’s Chitwan National Park, and Temenggor Forest Reserve in Malaysia.

There are also “Core Tiger Area Extensions” that merit protection – areas contiguous with Core Tiger Areas and which contain equal or better habitat capable of holding tigers in similar densities to the Core Tiger Areas to which they are linked. The aim of providing them the same levels of management and protection as Core Tiger Areas is so that they can be designated Core Tiger Areas as soon as possible. Examples of Core Tiger Area Extensions are Mae Wong in Thailand and Malaysia’s Balah Forest Reserve. Last but not least, there are also some sites de!ned as “Potential Core Tiger Areas”. These are areas that have lost most of their tigers but still have

Core Sites And Potential Core Sites – The Foundation For Recovery

© Ch

ris Ha

ils / W

WF-Ca

non

9The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

the potential to be Core Tiger Areas. With protection and management, the habitat and prey populations can recover, eventually allowing tigers to repopulate the area. These areas are the great hope for doubling the number of tigers and therefore are critical to WWF’s strategy.

A few places, such as Cambodia’s Eastern Plains, which today have no more tigers and are disconnected from remaining breeding populations, have the potential to become Core Tiger Areas. Reintroducing tigers into these areas is therefore the only option le!. However, as this is a very resource-intensive strategy, WWF will only consider it in areas with the greatest potential for recovery a!er the risks have been studied.

© Ch

ris Ha

ils / W

WF-Ca

non

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWF

-Canon

TIGERS ALIVE10

The Dawna-Tenessarims Landscape in Thailand is one of 12 landscapes WWF’s Tigers Alive Initiative has identi!ed as critical for the survival and increase of wild tigers. We are using it here as an example of our landscape approach.

The large map shows how WWF has divided the landscape into management units for a better understanding of what is necessary to facilitate its management. WWF is proposing a phased approach to achieve the goal of doubling wild tiger numbers by 2022. The two smaller maps indicate the landscape’s two distinct phases.

The maps give a good overview of Tigers Alive areas of activity leading up to 2022 and beyond. Areas of !rst focus are the Core Tiger Areas, considered the sites that have the most breeding females and so will act as the source of new tigers for the landscape. These breeding areas are the pivots around which WWF’s tiger

landscapes are designed. Core Tiger Areas need to be quickly secured to ensure that source tiger populations and their prey are protected. Core Tiger Area Extensions and Potential Core Tiger Areas are the obvious next targets for attention along with Critical Movement Corridors, which are the most threatened linkages in the landscapes.

The Dawna-Tenessarims Landscape illustrates the cohesive, holistic approach that WWF’s Tigers Alive Initiative embraces. It shows how WWF is pulling together resources at international, regional and landscape levels. With our partners, we are working in the large core area, together with the potential core areas in the north and south of this landscape, to support the Tx2 (doubling of tiger numbers) target. Also highlighted in the maps is the immediate prioritisation of movement corridors as pivotal in maintaining the integrity of the landscape.

Understanding a WWF Tiger Landscape

© Ro

bert St

einme

tz / W

WF Th

ailand

11The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Understanding a WWF Tiger Landscape

© Cra

ig Bruc

e / WW

F-Mala

ysia

TIGERS ALIVE12

1. Anti-poaching There must be zero tolerance for tiger poaching if we are to prevent the tiger’s extinction and recover wild populations. Therefore, Core Tiger Areas and other critical management units within the landscape, such as corridors, must be strictly protected.

The mechanisms required for this zero tolerance approach vary according to the site, but WWF aims to ensure that in all sites it supports, sta! of the forest and wildlife agencies are provided with equipment, vehicles, training and operational support. In some areas, these sta! collaborate with the military to combat poaching. In others, community patrols and informant networks are also deployed, but these happen more regularly outside protected areas.

Other support WWF is providing in the "ght against poaching includes:

Establishing strategic patrolling systems that are driven by information derived from informants and monthly enforcement review reports.

Standardising the training of all enforcement units, be they sta! of forest and wildlife agencies, army, police or multi-agency units.

Providing critical infrastructure support

for communications, mobility and e!ective patrolling.

Assisting local enforcement agencies develop and maintain structured, landscape-level informant networks that will collect and pass on standardised information.

Applying standardised enforcement monitoring systems using global positioning and other computer-based tracking systems. These tools enable adaptive management and

information-led enforcement by producing monthly and annual reports on a standard set of indicators from each protected area. WWF is rolling out computerised law enforcement monitoring systems such as MIST (Management

Information So#ware Tool), or its alternative, such as M-STrIPES in India, to support enforcement managers in adapting their patrolling strategies to enhance e$ciency and e!ectiveness.

Strengthening existing capacity by creating dedicated, highly trained mobile units in each landscape. These quick-response teams, comprising personnel from multiple agencies wherever possible, are becoming elite enforcement units operating both in and outside protected areas.

Working with the police and judiciary in raising awareness of wildlife crime prosecution.

Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

© Ma

rk Carw

ardine

/ WWF

13The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Community-based anti-poaching operations outside tiger landscapes

Poachers o!en "nd it safer and easier to poach wildlife in forests outside protected areas because of the lax security arrangements. In Nepal, WWF has formed community-based anti-poaching units comprising local volunteers, to respond to this challenge. Members are trained on safe patrolling techniques and the importance of conservation and laws and policies pertaining to biodiversity conservation in Nepal. In many instances these units have even braved armed poachers and apprehended them. For example, in May 2005, one such unit apprehended four tiger poachers, handing them over to the authorities for prosecution. These units are one of the best examples of community stewardship of natural resources and biodiversity.

As part of the strategic approach, we also have experts to advise our country and "eld o#ces on how to develop and implement appropriate programmes to support government counterparts in anti-poaching and anti-wildlife tra#cking operations.

Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

© Anu

p Shah

/ WWF

TIGERS ALIVE14Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

2. Protected area management and capacity buildingProtected areas are the backbone to all the landscapes and they cover most of the Core Tiger Areas. Thus, the success of any e!ort to save tigers from extinction and restore wild populations will depend on the e!ectiveness of protected areas as sanctuaries for tigers and their prey.

WWF has identi"ed the most important protected areas for the recovery of the tiger in each of our 12 focal landscapes. These include some of the most famous national parks and tiger reserves such as Nepal’s Chitwan National Park and Kanha Tiger Reserve in India. With limited resources available at any one time, WWF has now established a phased-plan to help increase the e!ectiveness of these protected areas. We will work with the authorities responsible for these areas to ensure they have the sta! capacity, skills, equipment and "nancing to protect the sites well.

Together with our partners, we are developing a system of standards for protected area management which we hope will be a hallmark of performance quality that can help donor organisations identify the best places for their investment, and for management authorities to prove their ability to protect tigers.

Protected area support in Eastern Cambodia

The Eastern Plains complex in Cambodia forms the largest extent of naturally functioning deciduous forest habitat remaining in Southeast Asia. Its conservation potential is huge, due in part to the remoteness of the area, its sheer size, and its status as one of the region’s largest protected area complexes. The complex comprises three protected areas – Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary, Mondulkiri Protected Forest, and Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary. Together with the Seima Protected Forest and Yok Don National Park in Vietnam, they represent the contiguous core of almost 1.5 million hectares of diverse protected area.

When WWF began supporting the area in 2004, Mondulkiri had only four unskilled rangers with no access to equipment. Today it has 33 trained rangers, and adjacent Phnom Prich has 31. All the WWF-supported rangers are equipped with communications equipment, a good "eld kit, cameras and GPS devices. All are trained in wide-ranging topics, including law enforcement, "rst aid, "eld navigation and wildlife identi"cation. WWF also built ten permanent outposts and four sub-posts – almost all with electricity and running water – in the two protected areas. Protection activities are monitored through specialised databases for both rangers and community rangers to enable e!ective adaptive management. A multi-agency, mobile enforcement team bolsters support to major "eld e!orts, focusing on addressing wildlife tra#cking in the province. A lawyer is also on hand to assist in prosecutions.

© Cr

aig Br

uce / W

WF-M

alaysi

a

15The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

3. Community outreach E!ective protection and management of habitat, tigers and their prey will depend heavily on the support of local communities living with or close to tigers. Where local communities use the forests intensively for subsistence, they are in direct competition for resources with the tiger. Where this

happens, the tiger inevitably comes o! worse. For tigers to survive in these areas, resource management solutions for local communities must be found. WWF therefore works with communities in our focal tiger landscapes to help them develop their livelihoods, reduce dependence on forest resources, and increase their support for conservation.

Restoring a vital corridor with local support

The Khata corridor in the Terai Arc Landscape of Nepal is the only remaining forest patch connecting the country’s Bardia National Park with India’s Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary. This connectivity provides a critical dispersal corridor for tigers. By 2001, however, the corridor was severely degraded, and further degradation could lead to an irreversible break in the connectivity between the two protected areas, thus limiting the movement of tigers across the landscape.

As local communities are true stewards of natural resources and their ownership of these resources critical for sustaining conservation, WWF initiated a forest restoration programme with their participation. WWF facilitated a handover of degraded forests to the local communities for management, and supported them in planting trees in fallow land, and controlling grazing and forest "res to promote natural

forest regeneration. At the same time, WWF implemented activities to improve livelihoods and generate income, reduce dependence on forests, encourage use of alternative energy sources like bio-gas, improve cooking stoves, and build small-scale irrigation schemes and other community infrastructure. To ensure sustainability, WWF supports local capacity building by establishing local institutions to continue these e!orts, as well as providing managerial and technical skills training.

These e!orts have led to signi"cant improvements in Khata’s forest. A comparison of conditions between 2001 and 2009 showed that the forest has increased both in quality and extent. The increase in forest quality and cover has turned Khata into a functional wildlife corridor, with tiger pugmarks a common sight. Camera-traps have identi"ed numerous tigers, showing that Khata is functioning as a dispersal corridor for tigers between two protected areas in Nepal and India.

© Tsh

ewang

R.Wa

ngchuk

/ WWF

-Canon

9

12

63

7

4

2

5

1

6

3

4

2

5

WWF country o!ces in the tiger range states are located in the capital cities to provide high-level policy support and central capacity building. WWF "eld o!ces in the focal tiger landscapes support teams on the ground, working with local partners including state, provincial and/or county governments.

Tigers Alive LandscapesAmur-Heilong – China and Russia Straddling the border between northeastern China and the Russian Far East, this landscape comprises forests of Korean Pine and Mongolian oak, which provide an important habitat for the Amur tiger and its prey as well as livelihood for the local economy. Illegal logging poses a major threat to the tigers. WWF is working to increase wild tiger numbers by establishing a contiguous, well-protected, well-managed habitat, including cross-border protected areas.

Kaziranga–Karbi Anglong – IndiaLocated in northeastern India, this landscape has an extensive network of protected areas providing shelter to the Bengal tiger and other wildlife such as Indian rhinos and Asian elephants. Challenges to tiger conservation include: retaliatory killing of tigers due to human-tiger con#ict; poaching of prey species; lack of adequate baseline data; inadequate protection in forests outside protected areas; illegal wildlife trade; and insu!cient support among local communities for conservation. WWF works with the Assam State Forest Department, the Karbi Anglong Autonomous District Council, other government agencies and local NGOs to address these issues.

Satpuda-Maikal – IndiaThis landscape in central India has some of the country’s best tiger habitat and best-known tiger reserves such as Kanha. It houses 30% of India’s total wild tiger population, and 13% of the global wild population. The main threats are habitat degradation, infrastructure development, and poaching of tigers and their prey. WWF aims to create tiger-friendly corridors between the reserves, and to provide strong support to combat poaching. This will be achieved by including tiger conservation measures and deploying dedicated mobile anti-poaching units in corridor forests.

Western Ghats-Nilgiris – IndiaThis landscape in southern India comprises some of the country’s "nest and most contiguous tiger habitats. It represents some of the best areas where tiger numbers can be signi"cantly increased in the near future. Increased human activity, such as poaching, infrastructure development and burgeoning tourism, is threatening breeding populations and leading to habitat fragmentation. WWF supports capacity building of government agencies, anti-poaching e$orts, strengthening legal mechanisms through inter-state collaboration, policy/advocacy to address unsustainable infrastructure development, and community engagement.

Greater Manas – Bhutan and IndiaThis large ‘tiger-friendly’ landscape is centred on the Manas World Heritage Site, bordering Bhutan and India’s Assam state. It stretches up into the highlands of Bhutan where tigers co-exist with snow leopards. With good protection, tigers can breed and disperse safely throughout the landscape. Key requirements are: harmonising landscape management to directly promote tiger conservation; solid baseline data for tiger and prey population status; enhancing security of the Manas Tiger Reserve and Ripu-Chirang Forest Divisions; involving local communities and sharing conservation bene"ts with them; and active engagement and transboundary cooperation between Indian and Bhutanese o!cials to conserve tigers.

Sundarbans – Bangladesh and IndiaThe Sundarbans is a cluster of low-lying islands in the Bay of Bengal, spread across India and Bangladesh, and famous for its unique vast mangrove forests and Bengal tigers. Living on a very varied diet including "sh and crustaceans, the tiger’s survival here shows its remarkable versatility. Sea level rise from climate change and loss of silt, which constantly builds up the delta, threaten the landscape. Human-tiger con#ict and poaching of tiger and its prey are also big issues. Exploring approaches to adapt to climate change, in#uencing policies to develop a new ‘vision’ for the delta, mitigating human-wildlife con#ict and livelihood improvement, are some of WWF’s activities here.

WWF Tiger Offices

WWF Tigers Alive Landscapes

Other Tiger Conservation Landscapes

8

11

10

12

1

9

7

8

11

10

12

Tigers Alive LandscapesTerai Arc – India and NepalLocated in the shadow of the Himalayas, the Terai Arc stretches from Nepal’s Bagmati River in the east to India’s Yamuna River in the west. Its pioneering innovative conservation approaches have made this a model for the recovery of the Bengal tiger, Asian elephant and Indian rhino. Threats to the tiger, however, remain and these include poaching, human-tiger con!ict and habitat loss and fragmentation. Key WWF activities include establishing community development schemes, mitigating human tiger con!ict through interim compensation schemes, anti-poaching activities, and strengthening enforcement and advocacy to ensure tigers remain in core areas and that critical corridors remain intact.

Forests of the Lower Mekong – Cambodia, Laos and VietnamThese forests are for the most part in Cambodia with small areas in Laos and Vietnam. Recent surveys have shown it is now unlikely there are many, if any, breeding tiger populations le" in this landscape. However, the vast remaining habitats and relatively low density of human populations present a unique opportunity for tiger conservation. Hence WWF considers it a restoration landscape with the possibility of reintroducing tigers. Since 2000, WWF has been developing a wildlife recovery area in the Eastern Plains of Cambodia. Field monitoring shows that the prey base is returning fast and WWF is replicating the approach in southern Laos.

Dawna-Tennaserim – Myanmar and ThailandThis rugged landscape of vast forest wilderness along the Thailand-Myanmar border supports one of the world’s largest tiger populations. The tigers are, however, threatened by habitat loss due to agriculture expansion, uncontrolled logging and infrastructure development, and poaching. Since 1993, WWF has played a critical role in the area. It continues to be a leading partner in securing a permanent conservation legacy in the landscape.

Banjaran Titiwangsa – MalaysiaThis landscape, which includes Peninsular Malaysia’s longest mountain range and largest national park, supports the country’s largest tiger population. It lies next to Thailand’s Hala-Bala forest complex, which contains Thailand’s southernmost tiger populations. Poaching of tigers is a major threat. WWF works in the newly created Royal Belum State Park and the Temengor Forest Reserve, a production forest that still supports a substantial tiger population. WWF aims to make Temengor Malaysia’s #rst Tiger Reserve.

Central Sumatra – IndonesiaSpanning the centre of Sumatra, this landscape connects Kerinci-Seblat National Park, one of the world’s largest protected areas containing tigers, to the Bukit Tigapuloh National Park and Riau Province’s lowland peat-swamp forests that are rich in carbon. It is highly threatened by deforestation for oil palm, and pulp and paper plantations. WWF works to reduce pressure from habitat clearance through monitoring forest crime, engaging with plantation owners on more forest-friendly behaviour, reaching out to local communities, and supporting government agencies on sustainable land-use planning and implementation.

South Sumatra – IndonesiaThe rich rainforests of southern Sumatra are critical for the Sumatran tiger, as well as the Sumatran rhinoceros and Asian elephant. Poaching and human-wildlife con!ict are major threats to the tigers. WWF is supporting anti-poaching teams with training, equipment, operational costs and salaries. It also works closely with local communities to reduce human-wildlife con!ict.

© Cr

aig Br

uce / W

WF-M

alaysi

a

TIGERS ALIVE18Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

4. Human-tiger con!ict mitigationAs tiger densities increase due to population recovery, or where there is loss of available habitat, tigers more frequently come into contact with humans. This leads to con!ict situations where livestock and at times even people are attacked. To reduce these encounters and stop revenge killings of

tigers, as well as maintain community support for tiger conservation, WWF works on both livestock management and emergency compensation and insurance schemes. As our goal is to double wild tiger numbers, "nding solutions acceptable to the people living alongside tigers is critical to the future recovery of the species.

Mitigating human-tiger con!ict

Many communities around tiger reserves in India are heavily dependent on their livestock for sustenance and income. For a poor farmer, losing cattle o#en means losing a major livelihood source, and when livestock are killed by tigers, tigers are o#en killed in retaliation. One solution to this crisis is intervention by the government to provide compensation to the farmer. Such interventions are generally slow and do not provide immediate relief to the farmer. Therefore it is essential they are handled in a prompt manner to avoid retaliatory action.

In 1997, in partnership with local NGOs, WWF initiated a cattle compensation scheme around Corbett Tiger Reserve in India. Under the scheme, the livestock owner is

given compensation almost immediately. Funds are routed through a local NGO and compensation is usually paid within 24 to 48 hours of the con!ict. Pre-inspection vigils are maintained to prevent retaliatory killings of tigers, and cattle carcasses are disposed of by burial or burning a#er inspection to prevent poisoning of the carcass (poisoned carcasses are sometimes put out as bait to kill the o$ending tiger).

The tragedy of human mortality from tigers is one that WWF always works to avoid. When it unfortunately occurs, we provide payments to the relatives to help with the funeral and its related costs.

Due to the success of these approaches in Corbett, they have been extended to other tiger reserves in India.

© Ala

in Com

post /

WWF-C

anon

19The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

5. Tiger and prey monitoring WWF uses science to inform us where and how to work, and how well we are doing. We monitor tigers and their prey at both site and landscape levels so as to continually evaluate and adapt our programmes to ensure tiger numbers are increasing in WWF-supported Core Tiger Areas.

The monitoring takes many forms depending on tiger density at the site. All our methods follow agreed international standards. This way, the monitoring results in the landscapes we focus on are comparable with those from other landscapes, and we can then share lessons learned across borders and between organisations.

In most areas we use camera-traps to photograph tigers, identifying individuals by their unique stripe patterns. In some areas we also use specially trained dogs to !nd tiger scat so that we can identify individual tigers by conducting DNA analysis on the scat. Monitoring is always undertaken in close collaboration with our government counterparts and o"en in partnership with other stakeholders, including local and international conservation organisations. Tiger science also helps us develop our programmatic interventions. In Nepal, for example, we are radio collaring selected tigers to see how they move out from Core Tiger Areas and use corridors in the landscape. The information will help us manage corridors more e#ectively for the tiger. In Sumatra, Indonesia, we have been studying the various land uses of the tigers in a fragmented landscape. In Malaysia, we are monitoring tigers in commercial forestry areas to understand how well they are doing outside protected areas.

Tiger monitoring and research in a challenging landscape

In Riau province in central Sumatra, forest clearance for large-scale oil palm, and pulp and paper plantations, is rapidly destroying both Core Tiger Areas and the corridors linking them. Research on tigers here presents some unique challenges. Two key issues have emerged: Is our protection in Core Tiger Areas e#ective, and how do tigers use this human-dominated landscape?

WWF has established two monitoring systems in the landscape – camera trapping in three core areas (including Tesso Nilo National Park where results have shown a stable to increasing tiger population) and an occupancy technique for the entire landscape. Both techniques have also been used to assess the various land uses by tigers in the landscape to determine how far they will venture into various non-natural forest habitats. A ‘probability of occurrence’ map has helped us to develop management guidelines for large-scale plantations. These guide the plantations in land management in a way that can best facilitate the passage of tigers through their land and between Core Tiger Areas to maintain a genetically healthy tiger population

© Ala

in Com

post /

WWF-C

anon

© WW

F Indon

esia /

Indone

sia Tig

er Rese

arch T

eam

TIGERS ALIVE20Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

6. Habitat management and landscape connectivityTigers need a lot of prey, which in turn need high quality habitat to thrive. Maintaining high quality habitat is therefore essential for the tiger’s survival. Habitat degradation due to human disturbance, livestock grazing, logging or invasive species is a problem throughout all the landscapes and even in most of the key protected areas. WWF works with local partners to remove the factors hindering tiger population growth, and implements habitat restoration that helps in prey recovery. We also work with scientists and managers to design habitat plans and support restoration e!orts in protected areas where possible.

Connecting habitats is, however, the most important consideration in the long-term. Tigers need room to expand, but their habitats are becoming increasingly fragmented and unsuitable. WWF has mapped each of our focal tiger landscapes in detail, including infrastructure development plans and projects which will fragment tiger habitat. Using these maps to drive strategic interventions, WWF invests in determining ways to protect critical corridors, advocates for tiger habitats to be considered in spatial planning processes, and seeks economic and social incentives for protecting these vast forests and maintaining connectivity.

21The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

WWF recognises that infrastructure development is an essential part of economic growth in many tiger range countries. We therefore promote the practice of “smart” or “green” infrastructure. This practice ensures that plans for roads etc., incorporate the need for habitat connectivity, and promotes tiger and prey conservation. Ultimately, smart green infrastructure should help rather than hinder tiger conservation in places where development is unavoidable.

Forest certi!cation in northeast China

Tigers o!en cross the border from Russia into northeast China, where large tracts of forest provide the potential for tiger recovery. However, local forestry practices have reduced fodder, and o!en led to dense forests empty of tiger prey. WWF has been promoting sustainable forest management and certi"cation under the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). In 2003 and 2005, the area’s "rst two demonstration sites acquired FSC certi"cates. By 2009, with FSC becoming widely accepted by government, scienti"c academies and the forestry industry, more than a million hectares of forest in northeast China were certi"ed. More forest areas will be FCS-certi"ed in the coming years, thus increasing the chances for tiger prey populations to rebound to healthy levels and enticing tigers into the region. We are also working with partners, including the logging industry, to develop “tiger-friendly” forest management guidelines to guide FSC-certi"ed concessions on how best to manage their forest for tigers and their prey.

Maintaining the integrity of a tiger corridor via legal intervention

The Chilla-Motichur corridor connects forests on both sides of the River Ganga within Rajaji National Park, located on the western most edge of the Terai Arc Landscape in India. The narrow corridor is vital in enabling the movement of large mammals between the forests.

A busy national highway and a rail track pass through the corridor, while an army ammunition dump lies in its centre. The government of India is relocating the ammunition dump. The highway and rail track, however, still pose a serious impediment to the free movement of animals. A decision to widen the highway had threatened the corridor, but pressure from conservationists led to two con#icting remedies being proposed – an 800-metre #yover for vehicles and two 100-metre overpasses for animals. The latter option would have led to a permanent break in the corridor. WWF lobbied hard with partner organisations and government agencies against construction of the overpasses. A!er an intense legal battle, India’s Supreme Court gave a verdict in favour of the vehicle overpass, thus protecting Chilla-Motichur.

© Dip

ankar

Ghose

© And

y Rous

e / WW

F

TIGERS ALIVE22Critical Actions In WWF Priority Tiger Landscapes

7. Finding innovative solutions to local problemsWhile WWF takes a large-scale, strategic view of landscape-based tiger conservation, it is well understood that every single component of this approach requires intensive long-term investment. Stopping the killing of tigers, maintaining prey populations, retaining high quality habitat and ensuring local communities do not come into con!ict with tigers all require innovative solutions. These solutions are very o"en dependent on #nding enough resources – or, simply, sustainable #nance.

WWF therefore invests in sta$ in each landscape to #nd long-term mechanisms that will facilitate sustainable solutions.

The work of these sta$ is very o"en about making sure government programmes, such as the provision of bio-gas stoves, are applied in strategic locations, or #nding partners who will establish incentives like ecotourism ventures for protecting tigers and prey. Armed with proven entrepreneurial skills, these sta$ look for opportunities and partners to ensure successful initiatives in the landscapes. Very o"en WWF’s role is to #nd a solution and demonstrate it so that local players have the con#dence and know-how to do it themselves. O"en too it is about #nding those with an incentive to protect tigers and working closely with them, even though they may not be conventional conservation practitioners.

Working with hunters in the Russian Far

About 80 percent of the Amur tiger’s range in Russia overlaps with hunting estates. The density of tiger prey, such as deer and boar, in these estates, correlates directly with the density of tigers. Higher prey densities help both tigers and hunters. Since 2004, WWF has been working with model hunting estates, helping to strengthen management plans, providing training and equipment to rangers, creating mineral licks for ungulates, tilling foraging #elds, and developing ungulate feeding grounds. As a result, the number of ungulates has increased two to threefold within #ve years, leading to a doubling of tiger numbers in these estates. The success of this approach has led to its wide replication in about 2.5 million hectares of Amur tiger habitat, or 15 percent of the tiger’s range in Russia.

© Tsh

ewang

R. W

angchu

k / WW

F-Cano

n

© WW

F Russ

ia

23The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Poaching of and tra!cking in tigers are major threats to the survival of the species. Wild tiger numbers will continue to decline towards the point of no return if concerted action is not taken to combat poaching, arrest tra!ckers and signi"cantly reduce demand for tiger parts and derivatives.

WWF – particularly our o!ces in tiger range and consumer countries and the TRAFFIC programme – is scaling up e#orts to eliminate tra!cking in tiger parts and derivatives. The goal is to ensure that by 2022, this illegal trade is at negligible levels and no longer a threat to wild tiger populations.

Eliminating the illegal tiger trade must be tackled through a combination of interventions aimed at di#erent

target groups and stakeholders. These interventions are focused on:

Trade research: Gathering information on illegal trade that links poaching of tigers to the trade chain that supplies end-use markets, and using this information to help target interventions.

Law enforcement support: Working with enforcement agencies, prosecutors and the judiciary, through sta# training, capacity building etc., so as to ensure e#ective intelligence-led law enforcement and prosecution.

Advocacy: In$uencing policy makers to bring about strong policies and legislation protecting the tiger, and the allocation of adequate resources to allow for e#ective implementation.

Eliminating The Illegal Tiger Trade

© Ada

m Osw

ell / W

WF-Ca

non

TIGERS ALIVE24

Trade research TRAFFIC’s research activities are aimed at di!erent groups of actors across the trade chain. Starting with landscape-level poachers, it moves via local middlemen and processors through to high-level traders, ending with retailers. TRAFFIC conducts strategic research and market surveys, monitors law enforcement e!orts (seizures, arrests and prosecutions), and tracks trends in consumer demand. The focus is on the 12 WWF priority tiger landscapes, as well as key trade hubs and transport routes, including those in China, India, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, the Golden Triangle (northeast Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, China), and the trade routes from South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal), Southeast Asia, and the Russian Far East, o"en through transit countries, to end-use markets. This knowledge enables informed engagement with law enforcement agencies to catalyse action against perpetrators of tiger tra#cking. Publication of strategic $ndings and analyses helps to motivate political will to increase enforcement capacity, e!ort and e!ectiveness.

Law enforcement support Government agencies responsible for wildlife law enforcement in tiger range countries o"en su!er from lack of capacity to combat tiger tra#cking e!ectively. Also, the changing dynamics of wildlife crime necessitate regular enhancement of skills and knowledge. Lack of political will, $nancial resources, and inter-agency and inter-governmental cooperation are all factors that contribute to failing law enforcement. To save the tiger from

extinction, it is essential that wildlife law enforcement capacity in the tiger range and consumer countries is raised to a level where it can compete with the crime syndicates operating in the tiger landscapes. To serve as an adequate deterrent, the number of successful

criminal investigations and e!ective prosecutions of those involved in poaching of and tra#cking in tigers must increase.

We will expand support to sensitise and build the capacity of enforcement and judicial agencies in the tiger range countries. We will continue to work with

prosecutors and the judiciary to help develop model cases for prosecution, and encourage governments to establish specialised, inter-agency wildlife law enforcement units. Providing support for governments to improve cooperation with neighbouring countries on transboundary smuggling is a critical aspect of this work, and includes the further development of regional wildlife law enforcement networks, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN WEN) and the South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network (South Asia WEN). Advocacy E!ective law enforcement requires strong policies and legislation. Governments of tiger range and consumer countries must be made aware of the importance of stepping up e!orts to combat poaching and tiger tra#cking, through establishing e!ective laws, implementing relevant international legislation, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and allocating su#cient resources to their law enforcement agencies.

Eliminating The Illegal Tiger Trade

© Wi

l Luiijf

/ WWF

-Canon

25The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Reducing Demand E!orts to combat poaching of and tra"cking in tigers need to be complemented by campaigns to reduce the demand for tiger products. The demand is driven by a highly diverse range of consumers from di!ering cultures and countries. Sectors of demand include:

tiger skins for use as garments or display in China and Russia;

tiger teeth and claws sold as curios in Sumatra, Indonesia;

tiger bones long used for traditional medicines in China, Vietnam and by the global Asian diaspora; and

tiger meat consumption in several countries.

As solutions-based approaches for one group may not necessarily work for another, an informed range of strategies must be employed.

Intensive captive breeding facilities (‘tiger farms’) and some ill-managed

zoos, mainly located in China and Southeast Asia, are fuelling demand for tiger parts and derivatives. Illegal trade from these captive sources mainly feeds the markets for products such as tiger bone wine and tonics, and tiger meat. As this in turn fuels demand for wild tiger parts and derivatives, strategies to reduce demand must address this issue.

TRAFFIC has a strong body of knowledge based on consumer behaviour research which has driven awareness campaigns in China, India, Vietnam and elsewhere in Asia. An alliance with the highest levels of government in Vietnam has driven a campaign speci#cally targeting government o"cials and business people, as major sectors of the market, not to consume illegal wildlife. Engaging the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies (WFCMS) and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) universities in China to stop the use of

© Wi

l Luiijf

/ WWF

-Canon

TIGERS ALIVE26

tiger parts in TCM is showing real progress. These partnerships o!er opportunities to isolate further the small group of users and businesses pro"ting from tra#cking in tiger products. TRAFFIC’s paper on demand reduction, Addressing Competing Demands (see www.cites.org/common/cop/15/inf/E15i-46.pdf), co-authored with a leading World Bank economist, has been recognised by partners and CITES Parties as a comprehensive analysis of the market’s complexity.

Our research and knowledge, as well as capacity to implement major campaigns put us in our unique position to address the demand issue. Concerted and coordinated action is, however, needed on multiple fronts at a scale and intensity far in excess of what has been attempted to date. We are therefore developing a holistic demand reduction strategy including campaigns aimed at tiger product consumers in the premier market destinations of China and Vietnam, as well as other Southeast Asian countries with ethnic Chinese communities, such as Thailand and Malaysia. Key stakeholders to target include the WFCMS, with its 157 members in 75 countries, the TCM universities, business and in$uential community groups.

Success with this demand reduction approach is achieved only when it is integrated with complementary e!orts in intelligence-led law enforcement, as well as political will and policy improvements. Hence, we will also leverage high-level government commitment, and messaging will remain a critical component of increasing awareness of policies, regulations and penalties against illegal tiger trade and consumption.

Controlling Tiger Tra!cking in Nepal

Nepal has been identi"ed as both a source and transit country for illegal trade in tiger parts from South Asia into the Tibetan Autonomous Region and elsewhere in China. Tiger skins for traditional Tibetan costumes, tiger bones for traditional medicine and tonic wines, and a host of other illegal wildlife products taken from India and Nepal’s tiger reserves, are ferried through the country by a covert network of middlemen from Kathmandu and elsewhere. Having a strong wildlife trade control programme in Nepal, with strong connectivity to both India and China, is therefore essential.

WWF supports Nepal’s government in recruiting informants at strategic trade points and mobilising a network of informants across the country. This support has led enforcement agencies in Nepal to make several seizures and apprehend notorious poachers and wildlife tra#ckers.

WWF has also been active in supporting training in judicial and enforcement agencies, including police and customs o#cers, on di!erent aspects of wildlife crime and wildlife trade law. We are working with South Asian governments to implement the goals of the South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network, set up a%er a groundbreaking agreement in Kathmandu between South Asian countries in May 2010.

Reducing Demand

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWF

-Canon

27The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

In the short term, tiger conservation is necessarily dominated by the need to secure the remaining small pockets of habitat supporting the last wild populations. In the longer term, the plan is to restore tigers across the 12 WWF priority landscapes. Reaching the goal of doubling the number of wild tigers in the next 12 years and further increasing the population a!er 2022 will require intact forest landscapes. These landscapes are under threat mainly by the expansive infrastructure development across Asia and habitat clearance for agriculture, forestry and other types of land development. Once gone, these landscapes will not be easy to replace. So e"orts must be made to retain them now.

It is impossible to invest across an entire landscape the same level of resources

required to protect a Core Tiger Area. Therefore, our actions at the landscape level are designed to have the widest impact, and focus on maintaining connectivity and large-scale habitat integrity rather than the intensive protection and monitoring required within a Core Tiger Area.

As a #rst step, tiger habitat needs should be considered in development planning. WWF has developed a “Tiger Filter”, a participatory computer-based system for modeling the best areas for conserving tigers and the impact of planned or proposed land-use changes or infrastructure development in these areas. This tool is available to national and international development organisations and large businesses for use in planning and in strategic and local environmental impact analyses.

Securing Tigerlands – Saving Tigers and So Much More

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWF

-Canon

TIGERS ALIVE28

Finding optimum solutions for tigers and developmentAlthough infrastructure projects comprise a trade-o! between service bene"ts and environmental costs, the "nal result need not be one of environmental losses. In fact, infrastructure projects can be vehicles for improving institutional and legal frameworks for natural resource management and leveraging funds for conserving otherwise unprotected habitat. Including tiger habitat considerations in infrastructure projects requires an appreciation for the extent of the services these projects could provide to the environment and local communities. Compensation schemes, such as transfer mechanisms from infrastructure projects to conservation funds, are one way that such projects can do measurable good for tiger conservation. WWF is working to establish legal mechanisms and pilot examples of such funds across the tiger’s range.

Protecting the 12 WWF priority tiger landscapes will provide for the expansion of wild tiger populations. If well managed, these landscapes can also provide many ecosystem bene"ts to humans, including clean water, non-timber forest products (such as fruits, nuts, mushrooms and herbs), and genetic materials for crops and pharmaceutical products. They can also deliver essential

bu!ering against natural disasters and promote climate change adaptation. They can also potentially provide economic bene"ts in the form of ecosystem services, sustainable resource use and ecotourism. As such, protection of the landscape’s natural

habitat can contribute to poverty reduction by providing a safety net of subsistence resources for the poor. WWF therefore helps to mobilise resources for the protection and management of these landscapes so as to provide homes for tigers into the future. We do so in the knowledge that these investments advance a far wider set of bene"ts.

Tigers as a premium on REDD+ projects

Money may not grow on trees, but forests can be worth a lot more now if we value the carbon they store. That is the idea behind the "nancing mechanism called REDD, or reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation. REDD rewards individuals, communities, projects and countries that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by protecting vital forests. New proposals for REDD, called REDD+, aim to ensure that the mechanism protects carbon

resources and the biodiversity resources found in forests. REDD+ will be able to support protection of critical tiger forest areas and restoration of corridors between these core areas. WWF, the World Bank and other partners are investigating a further, more innovative approach that o!ers carbon o!set opportunities coupled with tiger conservation. Paying a premium price for these o!sets may be attractive to those also concerned with climate change and tiger conservation.

Securing Tigerlands – Saving Tigers and So Much More

© Tim

Lama

n / W

WF

29The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

© Ha

rtmut J

ungius

/ WWF

-Canon

Conservation leases in the Russian Far East

The Korean Pine forests in the Russian Far East’s Amur region are critical for the Amur Tiger. These forests contain vast amounts of carbon that would be released into the atmosphere if they were destroyed. Pine nuts from the forests are harvested and sold by local communities and companies. The nuts are also a staple food for deer and pigs – the tiger’s prey. Over-harvesting of the nuts ultimately leads to less prey for the tigers. WWF, in partnership with the Government of Germany, KfW (the German Bank of Reconstruction) and local companies, secured the recovery and sustainable management of four Korean cedar pine nut harvesting zones totaling over 600,000 hectares. At least 25 to 30

Amur tigers live in these areas, which are now supported by a long-term conservation lease of 49 years. WWF’s management recommendations allow only a minimum amount of logging, thus saving the best tiger habitat and millions of tons of carbon. WWF is able to control all forestry operations of the leaseholders, and supports !ve ranger brigades, providing them with cross-country vehicles, snowmobiles and motorboats. Inspectors are also provided with the required !eld gear, while two stationary and three mobile checkpoints have been established to control entry into the areas. Due to the success of this approach, WWF is seeking partners to expand the programme to the other 400,000 hectares of Korean pine nut harvesting zones in key Amur tiger habitat.

Tigers and the Asia Century

The 13 tiger range countries have been addressing tiger and habitat management challenges for decades. But with many of the Asian economies in rapid growth, and several moving to developed nation status, there are concerns over the impact of these developments on biodiversity on the one hand, and awareness of the opportunity that greater wealth can bring to conservation, on the other. While rapid

growth can present challenges in that it can lead to deforestation and habitat destruction, many Asian economies and governments are now strong enough to intervene and e"ect real change in the race to save tigers. All that is needed is the will and political momentum. WWF pledges to continue our work with Asian countries on !nding solutions to the challenges their rising economies present for biodiversity and people.

Securing Tigerlands – Saving Tigers and So Much More

TIGERS ALIVE30

Together We Can Save The Tiger The tiger’s survival remains perilous. The epitome of beauty, mystery and power, its worldwide status as a representation of nature’s pure and graceful essence fascinates us all. A world without tigers is unimaginable. Yet it could happen in just two decades or less if we don’t redouble our e!orts and work new strategies and innovation into our conservation plans.

We can save the tiger – with the right mindset, political will, and, above all, by working together. Strengthening existing partnerships and forging new ones are therefore vital to WWF in

meeting the ever changing dynamics of tiger conservation and achieving the ambitious goal of doubling the number of wild tigers by 2022.

Working with a wide range of partners, sharing knowledge, skills and resources, and implementing diverse but complementary activities, we can truly make conservation history by saving tigers and, in doing so, save much more. We can recover and double their numbers, and ensure tigers and humans co-exist harmoniously for generations to come.

The Global Tiger Initiative

The World Bank has pledged to take proactive steps towards conserving the tiger. In 2008, it helped form an ambitious and powerful alliance to save wild tigers from extinction. Known as the Global Tiger Initiative, it is a collaboration between governments, major conservation NGOs, including WWF, and international agencies. Through this alliance, the World Bank will

drive consultations and dialogue with tiger range countries to garner support for tiger conservation at the highest levels. It is hoped that this alliance will lead to major partnerships to save tigers, such as the World Bank reaching out to other lending institutions to implement a framework for smart green infrastructure so that infrastructure projects do not harm tigers and their landscapes, but instead do measurable good for tiger conservation.

31The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Together We Can Save The Tiger

Our partners

As stewards of natural resources, local communities are powerful allies in the !ght against poaching, and resolving conservation issues, such as land and habitat management, and human-wildlife con"ict.

We work with governments, development

agencies and international institutions to ensure tiger conservation is included in national and regional economic

and development plans. We facilitate transboundary e#orts among tiger range countries.

WWF collaborates with both national and international NGOs on the ground, at the policy level and in mobilising support from the general public for tiger conservation.

Strategic partnerships forged with this sector can create innovative win-win solutions for corporations and tiger conservation.

The process began with the !rst global workshop on tiger conservation in Kathmandu in October 2009, and culminated with the Heads of Government International Tiger Forum in St. Petersburg in November 2010.$ Tow other meetings followed in the Kathmandu workshop: the 1st Asian Ministerial Conference on Tiger Conservation in Hua Hin, Thailand in January 2010, which adopted the goal of doubling willd tiger numbers, and the Pre-Tiger Summit Partners’ Dialogue meeting in Bali in July 2010, which saw the !rst dra% of the Global Tiger Recovery Programme.$

As a key player in the process, WWF facilitated dialogue within and between tiger range countries, worked with their governments and other partners to develop national tiger recovery plans, and garnered donor countries’ support for tiger conservation. WWF will remain active in this process as it evolves, and continues to work with governments and our partners towards a living Global Tiger Recovery Programme that is both holistic and e#ective in reaching the goal of doubling the number of wild tigers by 2022.

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWF

-Canon

© Jam

es Kem

sey / W

WF-M

alaysi

a

TIGERS ALIVE32

It is safe to say that Nissar Ali probably doesn’t remember the last time he went into town to watch a movie. The mahout at India’s Corbett Tiger Reserve loves the forest, and has dedicated his life to

protecting tigers and other wildlife. This dedication goes way back to 1973, when he walked for over a month just to get to Corbett from his home. Since then, he has spent the vast majority of his life patrolling

Corbett. He wakes at 5 am for his !rst patrol, following up with another in the a"ernoon. On days when the park is closed to tourists, he continues his patrols, sometimes ferrying rations to camps in the interior or keeping an eye on the forest with !eld sta#. He has had many encounters with tigers, and enjoys watching mothers bring up their cubs. “They even play hide and seek with you, and o"en win,” he chuckles. Like Corbett’s tigers, he has survived rough forests and rough times, but he cannot imagine any other life. He continues to spend all his time protecting the tiger and Corbett’s wealth of other wildlife. He would still rather watch the big cat’s life play out in front of him, than actors on a silver screen in a building walled o# from nature.

Celebrating Tiger Conservation HeroesThere are many tiger conservation heroes – people who are passionate about saving tigers, always working above and beyond the call of duty. We feature three here and take the opportunity to salute all those who are working tirelessly to save this magni!cent animal for humankind.

Together We Can Save The Tiger

Bhadai Tharu lives adjacent to the Khata Corridor in western Nepal’s Bardia district. He relies on the forest for !rewood and grass to supplement his livelihood. Bhadai’s life is not very di#erent from those who live on the fringe areas of

national parks, except that he survived a tiger attack, lived to tell the tale, and still champions conservation. On the morning of 6 January 2004, when he was with a group cutting grass in the forest, a tiger sprang on him.

Quick-thinking villagers raised a din and frightened the animal away. A badly mauled Bhadai was rushed to hospital. Although the doctors managed to save his life, he lost an eye. Despite the trauma, Bhadai is still committed to leading the management of the Gauri Mahila Community Forest User Group as its chair. He is remarkably composed about his encounter with the carnivore, “Animals are animals so we humans have to give them space and learn to coexist. We all depend on the forest so we must conserve and protect it.” Bhadai is devoted to the community forest and believes that by conserving the forest, local communities can reap other bene!ts. In 2004, WWF awarded Bhadai with the Abraham Conservation Award for his outstanding contributions to biodiversity conservation in Nepal.

From about 50 individuals just a few decades ago, the Amur tiger population in the Russian Far East and northeastern China today stands at around 450. The increase and current stable population of Amur tigers can in part be attributed to the tireless e#orts of Anatoly Belov. In 1994 Anatoly became Director of the Barsovy Wildlife Refuge, and in 1998 was supported by WWF to start the special anti-poaching brigade called “Leopard.” Since then, he and his team have caught approximately 1,000 poachers, con!scated hundreds of weapons, and brought dozens of criminal cases against those who killed tigers, Amur leopards and their prey. He is still going strong today, even a"er three attacks from poachers where he su#ered bullet wounds. Anatoly has stretched his e#orts beyond the call of duty. He

participates in patrolling, wildlife censuses and !re prevention activities in the huge area of Russia’s Primorsky Province where Amur tigers are found. He also has worked with the authorities in the neighbouring Chinese province of Jilin to patrol along the Russia-China border, removing snares and traps, and ensuring the arrest of poachers. For his valiant e#orts and invaluable service to Amur tiger conservation, WWF in 2010 gave Anatoly its highest conservation honour, the Duke of Edinburgh award.

© WW

F Nepa

l©

Ameen

Ahme

d

© W

WF Ru

ssia

33The WWF Tiger Conservation Initiative

Together We Can Save The Tiger

© Viv

ek R.

Sinha

/ WWf

-Canon

WWF Tigers Alive Initiativec/o WWF Malaysia

49 Jalan SS23/15, Taman SEA, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: ++ (603) 7803 3772 Fax: ++ (603) 7803 5157Email: [email protected] Website: www.panda.org/tigers

Cert no. SCS-COC-003429