Thursday, January 5, 2017 The Ntionl...

Transcript of Thursday, January 5, 2017 The Ntionl...

Thursday, January 5, 2017 www.thenational.ae The National business06

focusTransport

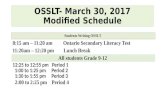

While ticket sales do not cover costs, the maglev service boosts output

TOKYO // The top operational com-mercial speed of the Shanghai Mag-lev Train, or Shanghai Transrapid, of 430kph makes it currently the world’s fastest train in regular service.

The train line, which opened in 2004, connects Shanghai Pudong Internation-al Airport and the outskirts of central Pu-dong where passengers c an interchange to the Shanghai Metro to continue their trip to the city centre. It cost US$1.2 bil-lion to build and was constructed by a joint venture of Siemens and Thyssen-Krupp of Germany, based on years of re-search and development of their Trans-rapid maglev monorail system.

The Shanghai maglev track, or guide-way, was built by local Chinese com-panies which, as a result of the alluvial soil conditions of the Pudong area, had to change the original track design of one supporting column every 50 metres

to one with a column every 25 metres . Several thousand concrete piles were driven to depths up to 70 metres to at-tain the necessary stability for the sup-port columns. A mile-long climate con-trolled facility was built alongside the route to manufacture the guideways. The electrifi cation of the train was de-veloped by the US electrical engineer-ing fi rm Vahle .

The line runs from Longyang Road station in Pudong to Pudong Interna-tional Airport. At full speed, the 30km journey takes 7 minutes and 20 seconds to complete , although some trains in the early morning and late afternoon take about 50 seconds longer.

The train can reach 350kph in two minutes, going on to its maximum nor-mal operation speed of 430kph.

The Shanghai Maglev Transporta-tion Development Company operates the line, which runs from 6:45am to 9:30pm, with services every 15 to 20 minutes. A one-way ticket costs 50 yuan (Dh26), or 40 yuan for those passengers with proof of an airline ticket purchase. A round-trip return ticket costs 80 yuan, and first-class tickets cost double the

standard fare. While much trumpeted at its opening, passenger numbers av-erage just 20 per cent of capacity.

Such low levels are attributed to limit-ed operating hours, the short length of the line, high ticket prices and the fact that it terminates at Longyang Road in Pudong – another 20 minutes by sub-way from the city centre.

The South China Morning Post has reported that the train “is increasingly becoming a white elephant”, while Chi-na’s offi cial Xinhua news agency report-ed Wang Mengshu, an academic at the Chinese Academy of Engineering and a professor at Beijing Jiaotong Universi-ty’s tunnel and underground engineer-ing research centre, as saying maglev trains are nothing but “transport toys”.

However, the Las Vegas-based man-agement consulting group Global Mar-ket Advisors’ senior partner Andrew Klebanow says it is easy to label a mass transit system that fails to achieve fore-cast results as a white elephant, particu-larly if that system employs new tech-nologies such as maglev.

While it is true that Shanghai has al-ternative mass transit options from the central city, subways are not as fast and do not offer the comfort and amen-ities found in the maglev, particularly for those commuting to the airport, he says.

“One need only try dragging a suitcase into a Shanghai subway during rush hour to appreciate the difference,” Mr Klebanov says.

The vast majority of the world’s urbanmass transit systems fail to generateenough ticket revenue to cover bothcapital costs and operational costs butthat does not make them economicallyunviable. Mass transit systems providetremendous benefits to society andthose costs, particularly the costs toconstruct those systems, must be borneby society, Mr Klebanow says.

“Imagine what New York City wouldbe like if it did not have a mass transitsystem. Or Singapore. Or Hong Kong,”he says.

Such systems generate returns on in-vestment that go far beyond repaymentof construction loans, Mr Klebanowsays. “They improve the quality of lifein cities and allow those cities with ef-fi cient, high-speed rail systems to gen-erate far higher levels of economic out-put,” he says.

Echoing that sentiment, the Ire-land-based journalist Eamonn Fingle-ton, who has written three books on theeconomies of East Asian countries, saysif the Shanghai maglev has been oper-ating at a loss, it would not be the fi rstpublic transit system to do so.

“From the point of view of the overallChinese national interest over the longhaul, the investment might well turnout to be an excellent one if it helpsteach the Chinese how to build moremaglevs to crisscross the country,” hesays.

*Richard Smith

Shanghai’s 430kph train benefi ts wider economy

TOKYO // A record-breaking high-speed train is under construction between Tokyo and Nagoya City, a distance of 286 kilometres, with a planned exten-sion to Osaka, another 139km.

Called Chuo Shinkansen and under construction since 2014, the bullet-train line is expected to connect Tokyo and Nagoya with a journey time of 40 min-utes compared to an hour on the exist-ing high-speed line the Tokaido Shin-kansen, and eventually Tokyo and Osaka in 67 minutes rather than 145 minutes, running at a maximum speed of 500kph.

The Chuo Shinkansen is the culmina-tion of Japanese maglev (magnetic levi-tation) technology development which has been ongoing since the 1970s. The first programme was a state-funded project initiated by Japan Airlines and the former Japanese National Railways. Central Japan Railway Company (JR To-kai) now operates the research facilities.

Maglev is a transport method that uses magnetic levitation to move vehi-cles without making contact with the ground. With maglev, a vehicle travels along a guideway using magnets to cre-ate both lift and propulsion, thereby reducing friction by a great extent and allowing very high speeds. The trainsets themselves are popularly known in Ja-pan as “linear motor cars”.

In China, the Shanghai Maglev Train, or Shanghai Transrapid, was the third commercially operated high-speed magnetic levitation line in the world and is currently the fastest . The first maglev in commercial operation was a low-speed shuttle that ran between the airport terminal of Birmingham In-ternational Airport and the nearby Bir-mingham International railway station between 1984 and 1995.

While the Shanghai Transrapid holds the speed title, the Chuo Shinkansen’s backers say the latter train has signifi-cant advantages. Whereas the Shanghai Transrapid is a normal conducting mag-lev, with a maximum speed of 430kph,

Japan bites bullet with maglevThe spiralling costs of a high-speed rail link not initially expected to use state cash has seen the government step in to provide fi nance. Some analysts question the wisdom of the project, writes Richard Smith, Foreign Correspondent

tion cost was estimated at ¥5.1 trillion (Dh160.16 billion).

The figure has since ballooned to around ¥9tn including the cost of the trains, MLIT’s Ishino says. With the spi-ralling cost, the Japan cabinet in Sep-tember adopted a bill that will allow the government to make unsolicited loans for building the line.

But construction costs will to a large ex-tent depend on issues such as the ease or otherwise with which the tunnels and bridges required can be built, above ground or underground stations and site costs, for example, Mr Ishino says. “Tunnels count for 70 to 80 per cent of the total length of the route with the ex-tension to Osaka included, so difficult construction is anticipated,” he says.

Tunnels are the primary reason for the project’s huge costs. Some 86 per cent of the line from Tokyo to Nagoya is planned to run in a tunnel, with some sections at a depth of 40 metres, over a total of 100km in the Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka areas.

The government hopes the new bill will help to get the Chuo Shinkansen running up to eight years ahead of the previous target of 2045 for completion of the extension to Nagoya.

JR Tokai estimates that Chuo Shin-kansen fares will be only slightly higher than Tokaido Shinkansen fares, up by about ¥700 between Tokyo and Nago-ya and around ¥1,000 between Tokyo and Osaka. The positive economic im-pact of the Chuo Shinkansen in reduc-ing travel times between the cities has been estimated at anywhere between ¥5tn and ¥17tn during the line’s first 50 years of operation, according to an-alysts quoted by the economic daily Ni-hon Keizai Shimbun.

Nevertheless, the Chuo Shinkansen has its critics. Shinichi Yamazaki, a sen-ior sector analyst at Okasan Securities’ corporate research department, believes that while constructing the line makes economic sense , it faces two major prob-

the Chuo Shinkansen, as a supercon-ducting maglev, can run faster, says To-moya Ishino, the trunk railway division chief at the railway bureau of Japan’s ministry of land, infrastructure, trans-port and tourism (MLIT).

In addition, “the Chuo Shinkansen can levitate at 10cm compared to the Shanghai maglev’s 1cm, so it is safer in case of earthquakes or other disasters”, Mr Ishino says, as the carriages have more clearance.

The line’s route passes through many sparsely populated areas in the Japa-nese Alps but is more direct than the current Tokaido Shinkansen route, and time saved through a more direct route was a more important c onsideration for JR Tokai than having stations at in-termediate population centres.

Also, the more heavily populated ex-isting Tokaido route is congested, and providing an alternative route if the Tokaido Shinkansen were to become blocked, following an earthquake for instance, was also a consideration.

JR Tokai announced in December 2007 that it planned to raise funds for the construction of the Chuo Shin-kansen on its own, without government fi nancing, to avoid government control. However, that was when total construc-

lems: the construction costs; and the length of time it will take to build.

Japan is in a rush for infrastructure construction ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and project costs are rising as the number of people working in the building industry is decreasing, Mr Yamazaki says.

“JR Tokai is planning to open the Shi-nagawa-Nagoya section of the line in 2027, but it is not clear whether it will fol-low the plan or not,” he says. For his part, Reijiro Hashiyama, a former visiting professor at Chiba University of Com-merce’s graduate school , has opposed the Chuo Shinkansen project for years.

Mr Hashiyama says JR Tokai will not be able to get a return on its invest-ment because of the line’s overly high construction and running costs, lack of passenger demand a s the popula-tion declines and he adds that he sees the doubling of routes between Tokyo and Osaka as unnecessary. The line will cost ¥22bn to build per kilometre, com-pared to only ¥5bn for the Shanghai maglev. And as the Chuo Shinkansen levitates 10 times higher, it will require 3.5 times more electric power than the Chinese train, Mr Hashiyama says.

As for the much-vaunted greater safety of Japan’s maglev technology compared to its Shanghai counterpart – two Chi-nese fast trains collided in 2011 near the city of Wenzhou south-east of Shanghai and dozens of people were killed – that is offset by the fact that the vast major-ity of the Tokyo to Nagoya line is under-ground, Mr Hashiyama says. His belief comes despite the fact that Japan has the safest, most punctual high-speed rail system in the world, according to Wharton University of Pennsylvania. “In case of an earthquake, a fi re or an acci-dent, we can imagine very high casual-ties,” Mr Hashiyama says.

For train line profitability, the funda-mental requirements are safety, reliabil-ity, punctuality, comfort , convenience, comprehensive network , adequate

speed, low energy use and affordablefare s, Mr Hashiyama says.

Regarding energy use, a maglev is moreeffi cient than a conventional train.

According to the US Centre for Trans-port Analysis at Oakridge National Lab-oratory, a standard intercity train run-ning at 130kph uses six barrels of oil per16,000 passenger kilometres whereasa maglev running at 485kph uses just0.46 of a barrel.

However, Mr Hashiyama says “themaglev’s biggest advantage is highspeed, so in this way it is an airplane. Butas a train the regular Shinkansen serviceis much more satisfactory,” he says.

For the maglev to really take advantageof its unique ly high speed, it needs tobe used on services that are direct andfrequent , long distance and with manypassengers every day, just like a com-mercial airline, Mr Hashiyama says.

“If this is not the case, the train com-pany will not be able to bear the defi citfrom construction,” he says.

Mr Ishino says the intrinsic safety of the Japanese maglev technology is astrong selling point for overseas cus-tomers, but Mr Hashiyama fi rmly disa-grees. “There is no country interested inmaglev technology today,” he says.

However, the Las Vegas-based man-agement consultant group Global Mar-ket Advisors’ senior partner AndrewKlebanow believes the United States,for example, would find it more eco-nomical to import such technologythan to try to develop it itself, although,“this is not to suggest that the US willembrace maglev technology”, he says.

US investment in its motorways andair transport makes it unlikely that thecountry’s policymakers will adopt a newform of mass transit, Mr Klebanow says.

But “other countries, where ‘masstransit’ is not a political term, could eas-ily embrace these new technologies”,he adds.

China // Transport

A 2013 ribbon-cutting event to mark the test run of a maglev train in Tsuru City. The maglev transport method uses magnetic levitation to move vehicles without making contact with the ground. Yuriko Nakao / Bloomberg

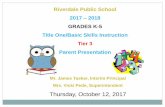

A maglev train at a platform in Shanghai Pudong Airport. Tomohiro Ohsumi / Bloomberg