The tokugawa period

-

Upload

school-of-foreign-service-georgetown-university -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

1

description

Transcript of The tokugawa period

The Tokugawa and the Emergence of

Modern Japan (1600-1868)

Teacher Resource Guide

East Asia National Resource Center

By Kelly Hammond

The Tokugawa The Tokugawa? The Tokugawa Regime?

The Tokugawa Period? The Tokugawa

Polity? The Tokugawa Bakufu? The

Tokugawa Shogunate? The Edo period?

With all these names floating around, it is

no wonder people get confused about the

period in Japanese history that scholars

usually describe as lasting from 1600 to

1868. “Tokugawa” is the clan name of the

family who managed to bring an end to a

period marked by continuous war and

destruction that plagued the Japanese

archipelago for centuries. The Tokugawa

family began the process of unifying Japan

into the modern polity that we imagine it

to be today. Following the disunity and

chaos of the Warring States Period, Oda

Nobunagu reestablished a centralized

government, but it was only after a

decisive battle in 1600 that the authority

of the state fell to Tokugawa Ieyasu (“EE-

eh-ya-su”). Tokugawa Ieyasu inherited

and expanded the political structures that

Oda Nobunagu had put into place. This

event marks the beginning of the

Tokugawa period and for the next 268

years a military-like government would

rule Japan with a Tokugawa clan member

at its head.

There were many changes to Japanese

society during the Tokugawa period. The

lasting peace meant that the population

grew, urbanization increased, and

infrastructure (e.g. roads and canals) and

communications improved. The period

was also accompanied by contentious

relationships with Qing China and

Western missionaries, indicating that

Japan constantly re-imagined its position

in the emerging global order of the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Before taking a closer look at some of

these changes to Japanese society, a few

more terms need to be explained and

defined.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa.

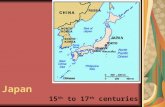

Edo and Tokugawa? Are They the Same?

Sometimes the Tokugawa period is

referred to as the “Edo period.” Edo (江戸),

which literally means “entrance to the bay”

or “estuary,” is the old name for Tokyo.

The Tokugawa clan established their

government—or the bakufu—in Edo.

Although Kyoto remained the official

capital, Edo became the de facto capital of

Tokugawa Japan and the center of

political power. Before this, Edo had been

a small village.

View of Edo Castle. Source: Castles of Japan

During the Tokugawa period, however, the

city grew to have about 1,000,000

inhabitants, rivaled only by Beijing for the

largest city in the world at the time. In

1868, Edo was renamed Tokyo, which

means “Eastern capital” (in relation to

Kyoto) and the emperor moved from

Kyoto to take up residence in Edo castle.

This is all to say that sometimes people

refer to the Tokugawa Period as the Edo

Period because it was during this time that

Edo rose to prominence as the center of

politics and social life in Japan. Tokyo

might not have become the global city that

it is today if the Tokugawa had not

established their de facto capital there in

1600.

Shogun? Bakufu? Daimyō? Samurai?

Translated into English, shōgun (将軍)

means “military commander” or

“generalissimo.” The shōgun was usually a

hereditary military leader of Japan

throughout the early modern period.

When Portuguese explorers arrived in

Japan, they described the relationship

between the emperor and the shōgun like

the one between the Roman Catholic Pope

(symbolic but little practical political

power) and a European King.

Map of regional breakdown of daimyo.

Source: Giant ITP

The shōgun’s office or their administration

is known as the bakufu (幕府), which

literally means "tent office." Sometimes

the bakufu is also called the “Shogunate”

in English. The tent originally symbolized

that the shōgun was a field commander

who often moved locations, thus

indicating that the position of office is

temporary. The shōgun’s officials were as

a collective the bakufu, and were those

who carried out the actual duties of

administration while the imperial court

retained only nominal authority. During

the Tokugawa Period, the effective power

of government rested with the Tokugawa

shōgun, not with the emperor who stayed

in Kyoto, even though the shōgun gained

his legitimacy by earning the emperor’s

official recognition. The shōgun controlled

foreign policy, the military, and the feudal

lords—or the daimyō.

Daimyō is a generic term referring to

powerful hereditary lords who ruled large

territories and clans in early modern

Japan. In the term “daimyo,” “dai (大)”

literally means “large” and the “myō”

stands for myōden (名田), meaning

“private land.” The daimyō of early

modern Japan are often compared to

powerful feudal lords who ruled kingdoms

in early modern Europe. Like feudal lords,

the daimyō were subordinate only to the

shōgun and the emperor.

Japanese Samurai in their traditional outfit.

Source: Journey to Orthodoxy

After the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600,

Tokugawa Ieyasu was recognized as

shōgun. He then reorganized roughly 200

daimyō based on their rice production

output and whether or not they had

supported the Tokugawa clan in their rise

to power. The Shogunate was never static

and power shifted constantly throughout

the Tokugawa period; each shōgun

encountered competition and challenges

to his authority. Daimyō often hired

samurai to guard their land and they paid

them in land or food. In contrast with

European feudal knights, samurai were

not landowners but the military nobility of

early modern Japan. Samurai came to

mean “someone who serves the nobility.”

During the Tokugawa period, the lasting

peace meant that samurai served less as

warriors but fulfilled more bureaucratic

and administrative roles.

The Tokugawa Bakufu and the

Policy of Alternate Attendance

Sankin-kōtai, or the policy of “alternate

attendance,” was a system established by

the Tokugawa that had all the daimyō

spend every other year at the Tokugawa

court in Edo and leave their family

members as “hostages” when they

returned to their lands. These “hostages”

were seen as a way of ensuring that the

daimyō would not rise in rebellion or do

anything against the wishes of the Shogun.

However, in reality, the hostages led very

normal and pleasant lives in the capital.

The daimyō of course, did not travel alone;

they brought large retinues numbering in

the hundreds and had to maintain

permanent staff in Edo as well as in their

homelands. Because the men brought very

few women with them to Edo (apart from

their wives and daughters, who were left

as hostages), the gender ratio in the

capital was extremely skewed, with almost

two men for every woman. This, in turn,

led to the establishment of brothels and

the expansion of courtesan culture. The

policy of Sankin-kōtai had numerous

other important impacts on Japanese

society; it increased the political control of

the Tokugawa shōgun over the daimyō as

they were forced to spend time away from

their lands and spend great deals of their

money to maintain a home at their castle

and in the capital; it increased the need for

roads and infrastructure between Edo and

the daimyō’s lands; and it also meant that

Edo would develop as a cultural center

around the many lords and their families

who now had to spend time in the capital

and had large incomes to spend on

entertainment, fashion, and food.

Samurai and the Story of the

Forty-Seven Ronin Samurai were the military nobility of early

modern Japan. By the end of the twelfth

century, samurai became almost entirely

synonymous with bushi, a word that was

closely associated with the middle and

upper echelons of the warrior class. The

idea of bushi originates from the samurai

moral code, stressing frugality, loyalty,

martial arts mastery, and honour. The

samurai followed a set of rules that came

to be known as bushidō—or the way of

bushi. While samurai numbered less than

10 percent of Japan's population in the

early modern era, samurai teachings can

still be found today in both everyday life

and in modern Japanese martial arts. The

philosophies of Buddhism and Zen, and to

a lesser extent Confucianism and Shinto,

influenced the samurai culture. Zen

meditation became an important teaching,

while Confucianism played an important

role in samurai philosophy by stressing

the importance of the lord-retainer

relationship, or the loyalty that a samurai

was required to show his feudal lord.

The Tokugawa clan seal. Source: Lemon-s

By the nineteenth century, there was a

paradoxical shift in the samurai culture; it

became more codified as an elite social

class, but also, their role as violent

warriors was cut-back by the Shogun who

was nervous about rebellion. When the

Tokugawa Bakufu forced the daimyō to

reduce the size of their armies, ronin

(浪人)—or master-less samurai—became a

large problem in Japanese society. One of

the most famous legends in Japan is the

story of the Forty-Seven Ronin, which

took place in the eighteenth century Japan.

The story tells of a group of ronin who

sought revenge for their lord after he was

forced to commit seppuku (ritual suicide).

Upon getting their revenge, the ronin were

captured and obliged to commit seppuku.

This true story gained a sort of mythical

quality within Japanese culture and the

Forty-Seven Ronin came to embody all the

virtues of a samurai: loyalty, sacrifice, and

honor.

Society and Culture in Tokugawa Japan During the Tokugawa period, Japan

experienced a new era of prosperity and

growth. The end of war period and the

establishment of the Tokugawa led to

quick expansion of the population, which

reached about 17 million people by 1650.

This growth was also facilitated by less

frequent epidemics and the introduction

of new, stronger rice strains. As the

population grew and economy improved,

commercial activities flourished,

connecting regions that had previously

been politically divided.

This growth in population also led to the

concentration of large numbers of people

in urban areas, which in turn led to the

growth of cities. Before, daimyō had lived

in walled castles, but wary of rebellion,

Tokugawa Ieyasu had redesigned castles

to have smaller walls and to be more open,

allowing more fluid flow of traffic and to

be less defensive structures. In tandem

with the increased agricultural output

owing to new types of grains, changes in

both urban and rural Japan contributed

substantially to the process of building a

strong state and an industrial economy in

the nineteenth century.

Illustration of Edo. Source: Museum of the City

In a way, then, the changes that happened

in Japanese society throughout the

Tokugawa period can be understood as

developments that led up to the Meiji

Restoration in 1868 rather than seeing the

Meiji Restoration as a rupture or a break

with the past (the Meiji Restoration will be

discussed in the next module).

Religion, Christianity, and

the Tokugawa Shogunate

Most Japanese people do not exclusively

identify themselves as adherents of a

single religion. Rather, they incorporate

elements of various religions in a syncretic

fashion known as Shinbutsu shugou or the

amalgamation of Shinto kamis and

Buddhism. Shinto and Japanese

Buddhism are therefore best understood

not as completely separate and competing

faiths, but as a multi-faceted and complex

religious system. This comprehensive

approach to religion suggests that

Japanese were often open and receptive to

new religious ideas, including Christianity.

When Christian missionaries from the

West first arrived in Japan, the Japanese,

compared to those in other parts of Asia,

were more open to the Christian teachings.

However, this did not last long as the

missionaries quickly began to manoeuvre

politically, much to the chagrin of the

Tokugawa shogun. After a few failed

attempts at banning Christianity, the

Tokugawa Shogunate crucified twenty-six

Christians—some of them Europeans and

some Japanese—and finally managed to

expel all the Western missionaries and

force the remaining Japanese Christians

underground.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, Japan was producing about

one-third of the world’s silver. Most of it

was heading to China in exchange for

luxury goods like silk and fine teas, but

when Europeans got wind of the fact that

there were large silver mines in Japan,

they began to reach out. In 1543, two

Portuguese ships arrived in Japan from

Macao, establishing trade relations with

the local daimyō and introducing the

locals to muskets. In the endemic warfare

of the time period, daimyō quickly realized

the value of these muskets and placed

large orders for them. Following right

behind the merchants were the

missionaries, who at first received a

relatively free reign and began converting

large numbers of Japanese to Christianity.

Initially, they were tolerated but soon after

they were expelled. It is likely that some of

the daimyō had become allied with some

powerful Jesuits and converted to

Christianity, so the shogun saw

Christianity as a threat to his political

order, not as some sort socio-religious

problem. In any case, the expulsion of the

Christians had a lasting impact not only

on the development of Japan as a nation,

but also on the way that Europeans wrote

about Japan. Until recently, this event was

seen as a “rejection” of the West and as the

“closing” of Japanese society to the world

during the Tokugawa and that society was

stagnant and non-changing.

Commodore Matthew Perry and

the Arrival of the “Black Ships”

Commodore Matthew C. Perry.

Source: U.S. Navy Museum

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry

arrived in Edo Bay with a number of war

ships and demanded that the Tokugawa

open trading ports to the Americans. He

left the Tokugawa with an ultimatum; he

would return in one year with more ships

and guns, and if the Japanese did not

concede to his demands, he would attack.

The Tokugawa shogun, aware of the

humiliation that the Chinese had suffered

in the Opium Wars with the British and

the subsequent treaties they had been

forced to sign, conceded to Perry’s

demands. In the past, this event was

explained by historians as “the opening” of

Japan after centuries of isolation and

stagnation. However, historians now

argue the idea that Tokugawa Japan was a

“closed” society is not a legitimate claim

and is rather a vestige of an out-dated way

of writing and thinking about history.

Japanese depiction of Perry.

Source: Brian Hoffert

Although the Tokugawa did take measures

to expel Europeans from Japan (apart

from a few Dutch) and completely quell

any sort of Christian influence, the idea

that they were completely shut off to the

outside world is out-dated, and frankly,

wrong. Through their connections with

the Dutch and other East Asian entities,

like Siam, China, and Korea, the

Tokugawa Shogunate had a good

understanding of the changes going on

around them and the events that were

shaping the early modern world.

Arrival of the West. Source: Library of Congress

In 1854, the Treaty of Peace and Amity

allowed the United States to begin trading

with Japan. Five years later, another act

was forced on the Japanese government to

open even more ports for trade with the

United States. While there were anti-

Western feelings among the Japanese

population, many people realized the

benefits of Western sciences and advanced

military technology. This led to division

within the country as different groups vied

to have their viewpoints heard about how

to approach modernization. In an attempt

to keep up with Western weapons and

defense, a naval training academy was

established in Nagasaki in 1855 under the

leadership of Dutch instructors. The

following year, a military school that

embraced Western ideas was launched in

Edo. By 1868, changes that had been set in

motion throughout the Tokugawa—and

perhaps expedited by Perry’s arrival in

Edo—led to the Meiji Restoration and the

effective end of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

We will explore these new developments

in the next module.

Useful Websites Accompaniment website for most popular college level textbook for teaching introductory courses for Modern Japan http://www.oup.com/us/companion.websites/9780195339222/ Narrative of the history of the Tokugawa period from Asian History, a reliable source for information about Asia on the Internet: http://asianhistory.about.com/od/japan/p/History-Tokugawa-Shogunate-Japan.htm A lesson about the different Shoguns and periods in the Tokugawa presented by a PhD student in Japanese history http://sakura-zen.blogspot.com/2011/01/lesson-in-history-shogunates-and.html A link to images from the Tokugawa period with good descriptions of the images, their sources and the context surrounding them http://www.artelino.com/articles/tokugawa_bakufu.asp List of all the Tokugawa Shoguns and their concubines and wives. http://www.lesleydowner.com/journalism/secrets-of-the-shoguns-harem/the-tokugawa-shoguns/ Short documentary about the Tokugawa Period http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjovMjPU9ug Five-part series about the Tokugawa Period http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQlxcz9U2x0 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3V5gVLPEvI http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WOGyzGWW7j4 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRrDg0uDJWQ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vHvmA

VSyUI History of the Tokugawa (Edo) Period hosted by the Government of Japan http://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2128.html Art from the Tokugawa (Edo) Period presented by the Metropolitan Museum of Art http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/edop/hd_edop.htm Art from the Tokugawa (Edo) Period presented by the Honolulu Museum of Fine Art http://honolulumuseum.org/art/exhibitions/11649-edos_zagat_guide_hiroshiges_grand_series_famous_tea_houses Anatomical and Scientific Illustrations from the Tokugawa Period showing medical methods before and after the arrival of Europeans http://pasolininuc.blogspot.com/2013/02/anatomical-illustrations-from-edo.html Great Maps of Japan—searchable and great ability to zoom http://www.bigmapblog.com/2012/japanese-map-of-tokyo-bay-1852/ Blog about women and material culture in late Tokugawa Japan http://www.tokyoedoradio.org/Project/Links/edoCombs/edoCombs.html Explaination and description of state and society in the Edo Period http://www.grips.ac.jp/teacher/oono/hp/lecture_J/lec02.htm Information about individual samurai and samurai culture in general http://www.samurai-archives.com/edo.html Interesting and thoughtful module hosted by the Asian education program at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco http://education.asianart.org/explore-resources/background-information/edo-period-1615-1868-culture-and-lifestyle

Faculty posting about the decline of the Tokugawa http://bhoffert.faculty.noctrl.edu/HST263/15.TokugawaDecline.html Naval Documents from the US Navy website of Commodore Perry’s visits to Edo http://www.history.navy.mil/library/special/perry_openjapan1.htm

Suggestions for Further Reading

Ambros, Barbara and Duncan Williams, eds.

Local Religion in Tokugawa History. Nagoya: Nanzan Institute of Religion and Culture, 2001.

Ambros, Barbara. Emplacing the Pigrimage:

The Oyama Cult and Regional Religion in Early Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Benedict, Ruth. The Chrysanthemum and the

Sword. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989. Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Japan in Print:

Information and Nation in the Early Modern Period. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Boxer, Charles. The Christian Century in

Japan, 1549-1650. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

Brown, Phillp C. Central Authority and Local

Autonomy in the Formation of Early Modern Japan: The Case of Kaga Domain. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Davis, Julie Nelson. Utamoro and the

Spectacle of Beauty. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

Dower, John with Timothy S. George.

Japanese History and Culture from Ancient to Modern Times: Seven Basic Bibliographies. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1995 (Second Edition).

Farris, William Wayne. Japan’s Medieval

Population: Famine, Fertility, and

Warfare in a Transformative Age. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006

Ferejohn, John A. and Frances McCall

Rosenbluth, eds. War and State Buildng in Medieval Japan. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010.

Friday, Karl, ed. Japan Emerging: Premodern

History to 1850. New York: Westview Press, 2012.

Goodman, Grant. The Dutch Impact on

Japan, 1640-1853. Leiden: Brill, 1967. Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan:

From Tokugawa Times to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009 (Second Edition).

Gramlich-Oka, Bettina, and Gregory Smits,

eds. Economic Thought in Early Modern Japan. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Guth, Christine. Art of Edo Japan: The Artist

and the City, 1616-1868. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Hellyer, Robert. Defining Engagement: Japan

and Global Contexts, 1640-1868. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Hurst, Cameron G. III. Armed Martial Arts of

Japan. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Jansen, Marius B. China and the Tokugawa

World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Jansen, Marius B. The Making of Modern

Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Katsu Kokichi. Masui’s Story: The

Autobiography of a Tokugawa Samurai. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993.

Maruyama Masao. Studies in the Intellectual

History of Tokugawa Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974.

McClain, James L. A Modern History: Japan.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.

McCLain, James L. and Osamu Wakita, eds. Osaka: The Merchants’ Capital of Early Modern Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Moran, J.F. The Japanese and the Jesuits:

Alessandro Valignano in Sixteenth-Century Japan. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Nakane Chie and Oishi Shinzaburo, eds.

Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1990.

Nosco, Peter, ed. Confucianism and

Tokugawa Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Ooms, Herman. Tokugawa Village Practice:

Class, Status, Power, Law. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Perez, Louis G. Daily Life in Early Modern

Japan. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002.

Ravina, Mark. Land and Lordship in Early

Modern Japan. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Rubinger, Richard. Popular Literacy in Early

Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

Ruch, Barbara, ed. Engendering Faith:

Women and Buddhism in Premodern Japan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Toby, Roland. State and Diplomacy in Early

Modern Japan: Asia in the Development of the Tokugawa Bakufu. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Totman, Conrad. Politics in the Tokugawa

Bakufu, 1600-1843. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Totman, Conrad. The Collapse of the

Tokugawa Bakufu, 1862-1868. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1980.

Vaporis, Constantine N. Tour of Duty:

Samurai, Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan.

Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Whelan, Christal. The Beginning of Heaven

and Earth: The Sacred Book of Japan’s Hidden Christians. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996.