The science of Peter Rabbit · Many of Beatrix Potter’s illustrations are on display at the...

Transcript of The science of Peter Rabbit · Many of Beatrix Potter’s illustrations are on display at the...

SMALLHOLDERS WITH BIG IDEAS

It is entry 2978 written in flowingfountain pen and indistinctfrom any other item. Marbled

hand-made paper which is nowdisintegrating decorates the hardbackcover of this register of researchsubmissions, begun in 1888 andcompleted nearly 40 years later.The book records scientific documents

accepted for discussion by London’s LinneanSociety, a natural history organisation.Today, only experts in cotton gloves mayopen it and leaf through its stiff pages. Nopage stands out until you take a closer look;submission 2978, read by the society onApril 1, 1897, is from Helen BeatrixPotter.While she was busy establishing Peter

Rabbit and JeremyFisher as householdnames, Potter wasalso polishing herskills as an amateurscientist andscientific illustrator.Fascinated by

lichens, fossils andparticularly fungi,she drew andpainted natural life

during holidays in Scotland and the LakeDistrict, and specimens sent to her bynaturalist Charles McIntosh. McIntoshbecame an influential mentor and suggestedimprovements to make her sketches “moreperfect as botanical drawings.” Potter’sresearch paper to the Linnean Societyfeaturing her illustrations was the only oneshe wrote, however.Even so, she is regarded today as an

amateurscientist aheadof her time.

“She made acontribution of

observations that werenot known at the time,”says professor Roy Watling,former president of theBritish Mycological Society.“She was an extremelygood draftspersonillustrating what she saw -which is often not the casewith people doingillustrations of biologicalthings. Like Leonardo da

Vinci she actually drew what she saw ratherthan copying from a book.”Potter was born in London in 1866 but

spent many of her early summers with herfamily in Perthshire fostering her interest innature.A sketchbook dated 1875 contains

illustrations of birds, butterflies andcaterpillars. They are thought to be her firstdrawings of wildlife. She was painting froma microscope at 19-years-old and two yearslater illustrated a fungus forthe first time - theblue-green verdigristoadstool.

Many of Beatrix

Potter’s

illustrations are

on display at the

Victoria & Albert Museum

July 201322 Smallholder Visit us at smallholder.co.uk

BY CATH HARRIS

The science ofPeter RabbitThe science ofPeter Rabbit

She would spend hours observing anddrawing animals including her collection ofinsects, a hedgehog, mice and bats. Her petrabbit, Benjamin Bouncer, was the model for1889 Christmas cards. The accuracy withwhich she drew fungi mirrored the

precision with which she depicted hercharacters. Potter was attracted by the coloursof fungi and its fleeting character – the way itwould appear overnight apparently fromnothing. She is thought to have made the firstdrawings of the fungus responsible for larchcanker, which mycologists confirmed onlymany years later, and identified throughillustration the asexual reproduction of fungi,about which little was known.Her findings, though unacknowledged, that

a fungus’s mycelium - its generator - couldbreak up into smaller parts and potentiallyspread on the backs of insects, was hugelysignificant. Scientists knew that spores weredistributed on the wind but the discovery “100years on that mushrooms and toadstools havean asexual stage was quite awe inspiring,”Professor Watling says.It was the germination

of the spores of oneparticular groupof fungi –agarics, withumbrella-likecaps and gillsbeneath – which wasthe subject ofPotter’s researchpaper in 1897. ‘On theGermination of theSpores of theAgaricineae’ was “wellreceived” by theLinnean Societyaccording to another ofher mentors, Kewfungologist andLinnean Fellow GeorgeMassee.The Society requested

more work on the paperbefore it couldbe printed butPotterwithdrew herresearch a weeklater and neverre-submitted it.The manuscriptis lost butmany of herimpressiveillustrations are

on display at London’s Victoria & AlbertMuseum, Perth Museum in Scotland and atthe Armitt Museum in Ambleside to markthe Armitt’s centenary this year.Mycologist Ali Murfitt played Potter in a

recent reconstruction of theLinnean discussion of Potter’sresearch paper. Murfitt describesPotter as “an amazing scientistand a great observer”. “Herillustrations were so accuratebut she also developed her ownecological theories to try to

understand what was going on,”Murfitt adds. “She had a very inquiringmind and in her journal, wrote ‘onesees them because one has an openmind not stuck in a groove.’” Potterwas bridging the gulf between fairytale and science.As a woman and amateur, Potter

faced many battles in trying to wincredibility for her work. “It wasdifficult to find advice and to suggestideas without being laughed at,”Murfitt says. “George Massee was theonly person at Kew who came around to herideas and that took a while. Who knows whatshe would have come up with had she beenwelcomed into the scientific community?”Those obstacles, the success of her books

and associated merchandise, and theincreasing amount of land she was farming in

the Lake District, mayhave deterred Potterfrom further scientificdiscovery. She wasbecoming achampion of

Herdwick sheep andby her death in 1943 hadamassed 17 farmscovering 4,000 acres,which she left to theNational Trust.Potter’s scientific legacy

lives on and in 1997, 100years after herpaper was submitted, theLinnean Society pledged topublish theresearch if it

was found. She“had the mind ofa professionalscientist andbiologist – whichis what she undoubtedly would

have been had she lived at alater age,” wrote Dr WalterFindlaywho published 60 Potterillustrations in his bookWayside and Woodland Fungi.In the treasure trove which is the

Linnean’s 90,000-strong collectionof some of the most valuable

natural history studies, listing2978 is very much at home.Fungi are neither plants nor animals

belonging to their own separate kingdom,known as the fifth kingdom. They are madeup of microscopic thread-like structureswhich absorb nutrients. There may be up tofive million fungi species worldwidealthough only 100,000 have been identified.Often we are only aware of them asmushrooms or moulds – their fruiting state –but the fungi family also includes puffballs,tree brackets and the mould Penicillium.Around 90 per cent of vegetation worldwiderelies on fungi for nutrients in what is called.These plants range from the shrunken

species of the Arctic and Antarctic to thefulsome trees of the tropics. In the UK, “oaks,beeches and pine trees are all dependent onfungi living on their roots, and ash, sycamoreand lime depend on fungi living inside theirroots,” Professor Watling says. Mostly therelationship is symbiotic with the exception

of orchids which are parasitic. “Fungi givethe plant competitive betterment over otherplants” and return the favour by passing backsugars and proteins via their roots.Beatrix Potter bought Hill Top Farm in Near

Sawrey in the Lake District in 1905. She wasbreeding Herdwick sheep within a yearadding livestock and poultry soon after. Shebought Castle Farm in the same village in

Smallholder 23July 2013 Visit us at smallholder.co.uk

The accuracy of her drawingswas informed by first-hand

observation

Beatrix Potter bridgedthe gulf between fairy

tale and science

THIS MONTH: BEATRIX POTTER

1909 but after marrying William Heelis inLondon three years later continued to writeand paint from Hill Top.She was a keen supporter of the National Trust

and contributed funds from the sale of50 Peter Rabbit illustrations to theTrust’s campaign to stop

development on the shores ofWindermere.In 1930 aged 63, she bought

5,000-acre Monk ConistonEstate on condition that theTrust bought half of it from

her once funds wereraised. She continued

managing all ofthe land and took onother Trust farms.Her Herdwick

sheep were already medal winners when in1943 she was elected next President of theHerdwick Sheep Breeders’ Association fromthe following year. Had she lived, she wouldhave been the first female to hold the post.Potter suffered heart trouble and contractedbronchitis later in 1943 dying just before

Christmas of that year. She left 17 farms, eightcottages and more than 4,000 acres to theNational Trust.Judy Taylor has been a member of the

Beatrix Potter Society “since forever” and

recently became a vice-president. Theorganisation has several hundred membersacross the globe. Potter’s books areparticularly popular in the US and Japanwhere a three-part documentary is beingmade about her. Typically for the time, Potterwas educated at home by a governess.“What is so strange is that she and her

brother Bertram were allowed to keep pets intheir nursery and school room,” says Judy,who in turn spent much of her home timereading Potter’s books. I was brought up onBeatrix Potter stories and when I became achildren’s book editor I realised how brilliantthey are. She was extremely intelligent and avery talented artist and I’m full of admirationfor her scientific work. It doesn’t surprise methat she became so involved andknowledgeable.” n

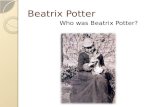

Beatrix Potter withher pet rabbit,

Benjamin Bouncer

July 201324 Smallholder Visit us at smallholder.co.uk