The Public Utility Pyramids

Transcript of The Public Utility Pyramids

The Public Utility Pyramids

Paul G. Mahoney

University of Virginia School of Law

580 Massie Road

Charlottesville, VA 22903

Draft of January 2008

Abstract

In the 1920s and 1930s, many public utilities in the United States were controlled by

holding companies organized in pyramid form. The holding companies’ critics claimed

that they extracted wealth from their subsidiaries’ other shareholders. Other

commentators argued that holding companies increased the value of subsidiaries by

reducing their financing costs. I examine the effects of the Public Utility Holding

Company Act of 1935 (HCA), which outlawed pyramid structures. The value of both top

holding companies and their subsidiaries fall (rise) around the time of key legislative

events suggesting a higher (lower) likelihood that the HCA would be enacted, supporting

the hypothesis that holding companies added value. I also find that the valuation effects

are most pronounced for financially distressed companies, suggesting that investors

expected the HCA to force liquidations that would destroy option value.

2

THE PUBLIC UTILITY PYRAMIDS

Paul G. Mahoney

I. INTRODUCTION

The presence of a controlling shareholder can be good or bad news for the

remaining shareholders. Equity ownership aligns the controller’s interests with those of

the other shareholders, leading it to monitor management (Jensen & Meckling 1976).

When the firm is subject to regulatory or political oversight, particularly when that

oversight is corrupt, a politically influential controller can protect the firm from the

“grabbing hand” of the government (Shleifer & Vishny 1998). A controlling shareholder

can also operate an internal capital market among its subsidiaries, which may reduce

financing costs (Gertner et al. 1994). These potential advantages come at a cost,

however. The controller may redistribute wealth from the other shareholders to itself by

diverting corporate assets or cash flows (Shleifer & Vishny 1997).

Not surprisingly, then, empirical evidence on the association between ownership

concentration and firm value is mixed. Some studies find a nonlinear relation between

ownership concentration and corporate valuation or performance, while others find no

connection or one that depends on the type of controlling shareholder (Demsetz & Lehn

1985; Holderness & Sheehan 1988; Morck et al. 1988; McConnell & Servaes 1990).

More recently, Claessens et al. (2002) argue that the positive incentive effects of

concentrated ownership are a function of the controller’s cash-flow rights while the

negative effects are a function of voting rights. Large shareholders sometimes use

devices such as non-voting shares or pyramid ownership structures to amass votes in

excess of cash-flow rights. Claessens et al. (2002) find that increased cash-flow rights

3

are associated with higher valuations in a sample of East Asian companies, while

increased voting rights are associated with lower valuations. Edwards and Weichenrieder

(2004) obtain similar results for a sample of German firms. Faccio et al. (2001) find that

the misappropriation problem is particularly acute for firms in which the ultimate

controller has less than a 20% economic stake. Attig et al. (2004) find that a gap between

control and cash-flow rights is associated with lower liquidity for the remaining shares.

This paper exploits a unique opportunity to observe the effects of separating cash

flow and control rights. During the 1920s and 1930s in the United States, most of the

public utility industry was organized in pyramid form. A small number of top holding

companies, through one or more layers of intermediate holding companies, controlled a

large portion of the nation’s operating electric and gas utilities. In 1935, however,

Congress enacted the Public Utility Holding Company Act (“HCA”), which limited

holding companies to owning a single, geographically contiguous operating system and

prohibited more than a single holding company tier atop any operating company. The

HCA led to a dramatic reorganization of the utility industry, including the elimination of

pyramid structures.

Different observers of the holding company pyramids had widely divergent views

of their purposes and effects. Many argued that top-tier holding companies used their

control rights to sell services to their operating subsidiaries at inflated prices. Others,

however, argued that the holding company structures were an efficient response to the

large fixed capital requirements of an operating utility. By bundling together the

idiosyncratic risks associated with individual utilities, each operating in a limited

geographic area, the holding companies could raise money more cheaply than could those

4

individual operating companies (Hyman 1985). Simply merging many operating

companies into a single diversified corporate entity would have been more costly because

it would have necessitated difficult political negotiations, possibly including bribes, to

transfer existing municipal franchises to the new entity.

I attempt to resolve the debate by studying utility holding company returns around

the time of key events leading up to the passage of the HCA, focusing on the differences

in returns between controlling and controlled companies. If the former indeed extracted

value from the latter, we should observe that the prospect of mandatory dissolution of

holding companies decreased the value of controlling companies but increased the value

of their subsidiaries. By contrast, if pyramid structures economized on financing costs,

then the value of both controlling and controlled companies should fall when

shareholders anticipated enactment of the HCA.

The results support the second hypothesis. The value of both controlling and

controlled companies fall (rise) by statistically and economically significant amounts

around the time of several key votes indicating a higher (lower) likelihood that pyramid

structures would be banned.

I then analyze cross-sectional differences in the abnormal returns among the

sample companies. The controlling companies, on average, lose more value during these

periods than do controlled companies. Nevertheless, the net effect of the HCA on

controlled companies remains negative. It is accordingly possible that being a subsidiary

of a holding company had both costs and benefits (the benefits including cheaper

financing and the costs including some wealth extraction), but the costs were not

5

sufficient to make dissolution of the holding company system a net plus for the subsidiary

companies.

I look for other variables that may explain the cross-sectional variation in the

impact of the HCA. One clear candidate is the financial soundness of the particular

holding company. Some holding company systems were very highly leveraged with

much of the debt concentrated in the top-level or intermediate-level holding companies.

Were these holding companies to be dissolved, they would have to pay off their debts

using the proceeds of sale of the operating companies. The net effect would be that

financially distressed holding companies, like any financially distressed company that is

liquidated, would lose a valuable continuation option. When a company’s assets are

currently worth less than its debts but may in the future be worth more, the ability to

avoid liquidation preserves a valuable real option. Liquidating the utility holding

companies, as the HCA required, would require prematurely selling the subsidiaries and

repaying the holding company’s debts, thereby extinguishing this option value and

ensuring that the holding company would be worth less in liquidation than as a going

concern. The gap between liquidation and going-concern value should be less for a

financially healthy holding company because liquidation would not extinguish a valuable

call option.

In fact, a company’s nearness to financial distress is a strong predictor of its

abnormal returns around the time of key legislative events. On average, utility holding

companies with “A” or higher debt ratings suffer dramatically smaller declines in value

around the passage of the HCA than do holding companies with poorer debt ratings. The

6

result is robust to using a simpler measure of whether the company is part of a financially

distressed holding company system.

The paper seeks to contribute to three different strands of the literature. Several

papers cited above attempt to estimate the effect of controlling shareholders on the value

of the publicly-traded shares. The fact that shareholders choose to seek control of some

firms but not others, however, complicates the analysis because the controller may be

attracted to firms that are undervalued or firms that are particularly susceptible to

misappropriation. The HCA was an exogenous event that affected all multi-layer utility

holding company structures and therefore provides a clean test of the effects of (losing) a

controlling shareholder.

There is also a substantial literature that seeks to explain the structure of the

public utility industry, including a longstanding debate over whether franchise

monopolies combined with state regulation is a natural response to economies of scale or

the consequence of regulatory capture (Demsetz 1968; Jarrell 1978; Priest 1993).

Recently, Hausman and Neufeld (2002) contend that utilities sought state regulation not

to gain the ability to charge a monopoly price, but rather as a way to make earnings

predictable and thereby reduce borrowing costs. The results herein provide indirect

support for Hausman and Neufeld’s view that the industry’s structure was primarily a

response to its large capital needs.

Finally, a recent literature in finance studies how country-level policy and

institutional differences interact with firm-level governance differences to determine the

behavior of managers and controlling shareholders and accordingly firms’ cost of capital

(Durnev & Kim 2005). The results in this paper suggest that, in a generally high-quality

7

institutional environment, firms may be able to reap the benefits of having a controlling

shareholder without suffering from substantial wealth misappropriation. This was

perhaps particularly true for the utility holding companies, which needed almost

continual access to the capital markets and therefore had a strong incentive to maintain a

reputation for not treating investors unfairly.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II provides

background on the utility industry, the growth of pyramid structures, and the legislative

battle over holding company regulation. Section III describes the data, hypotheses, and

tests. Section IV describes results, and Section V concludes.

II. UTILITY PYRAMIDS

A. Development

Early utility companies in the U.S. were primarily small, local, stand-alone

entities. From an early stage, however, local utilities began to consolidate. The

geographical scope of consolidation increased as energy demand soared in the early 20th

century. Between 1920 and 1930, a period in which real gross national product increased

by 31%, electricity and natural gas consumption both more than doubled. In 1920, 35%

of all residential units and 1.6% of farms were connected to the electrical grid. By 1930,

these had increased to 68% and 10%, respectively.

These developments required substantial new investment. The generating

capacity of non-government-owned electric plants increased from approximately 12

million to 30 million kilowatts between 1920 and 1930. Utilities consolidated in order to

be able to raise the funds required for new investment, utilities consolidated. Indeed, the

public utility pyramids came about largely through acquisitions.

8

Utilities combined by forming holding companies that purchased the stock of

multiple operating companies. In many instances, the difficulty of transferring franchises

or made it too costly to merge the operating companies into the parent company. These

holding companies, in turn, were often acquired by larger companies. The “super”

holding companies at the top of the pyramids often managed construction and financing

of new plants for their operating properties and provided centralized management. Some

of these holding companies were in turn controlled by construction companies or

investment banks. The resulting consolidation, achieved primarily over a 20-year span,

was dramatic. By 1930, the ten largest holding company systems generated

approximately 75% of the electrical power sold by utilities (Bonbright & Means 1932).

Some commentators saw in the pyramid structures an efficient reaction to the

industry’s massive capital needs. An individual local utility was often not large enough

to attract the attention of financial intermediaries. It was also subject to a variety of

diversifiable risks, including the risk associated with the regional economy and the risk of

local political interference. A large holding company, by contrast, could borrow large

sums at a lower rate than its individual operating companies. [cite Hausman]

Other commentators, by contrast, believed the holding companies were

pernicious. Their primary claim was that holding companies appropriated wealth from

minority shareholders of lower-tier companies by selling those companies construction,

investment banking, managerial, and other services at inflated prices. A second, related

objection was that holding companies made local rate regulation ineffective through their

ability to manipulate the operating companies’ costs.

B. The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

9

Critical commentary on utility holding companies began to appear by the late

1920s. Several articles in the legal literature called for regulation. In 1928, the United

States Senate ordered the Federal Trade Commission to investigate utility holding

companies. The investigation lasted until late 1934 and generated a report of more than

70 volumes.

The scrutiny and criticism became much more intense in the wake of the 1929

market crash, which hit highly leveraged holding companies particularly hard. The Insull

utility group, one of the country’s largest, was unable to meet its obligations. Its creditors

forced it into bankruptcy in 1932. The Insull collapse, which the press called “the biggest

business failure in the history of the world,” triggered a political reaction similar to

Enron’s 70 years later. Samuel Insull himself fled the country facing criminal charges of

embezzlement and larceny, of which he was eventually acquitted.

Franklin Roosevelt cited Insull as a symbol of financial fraud during his 1932

campaign. The Democratic platform called for regulation of holding companies. During

the initial months of his Presidency, however, Roosevelt chose to make the market for

new security issues the focus of financial regulation. The President and his advisers had

already determined the basic thrust of the regulatory regime for new issues—mandatory

disclosure of basic information about the issuer, the promoter, if any, and the

underwriting arrangements—and had a model at hand in the English Companies Act

(Mahoney 1995). After enactment of the Securities Act in mid-1933, Roosevelt turned to

the task of regulating the stock exchanges, which was completed with the enactment of

the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Then attention shifted to utility holding companies.

10

In July 1934, President Roosevelt established a National Power Policy Committee

to study the public utility industry and propose legislation. Political and market

commentators were unsure whether the legislation would be regulatory or prohibitive.

Based on the experience of the Securities Act and the Securities Exchange Act, there was

ample reason to believe that the legislation would focus principally on disclosure,

requiring holding companies to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission

and provide detailed information about the cost of the services they provided to

subsidiaries. At the same time, some of the President’s advisers advocated that holding

companies be abolished altogether or that structures with more than one layer of holding

companies be prohibited.

This uncertainty persisted up to the introduction of the administration’s bill. On

November 21, 1934, the New York Times reported that according to an “authoritative

source,” the committee would recommend a ban on pyramid structures. However, in a

year-end article on the main issues confronting Congress in the coming year, the Times

spoke merely of the possibility of federal regulation of utility holding companies. The

President’s State of the Union address on January 4, 1935 highlighted the uncertainty.

Roosevelt called for “the abolition of the evil of holding companies” and was asked in a

subsequent press conference whether he had decided to do away with holding companies

altogether. He responded that he had intended to advocate abolition of “the evil features

of holding companies” (as was contained in the printed copy delivered to the press).

According to the New York Times, the speech “led to both favorable and unfavorable

inferences” about the future of holding companies.

11

On January 11, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Sam Rayburn, gave

a speech on the House floor stating that he wanted to “eliminate rather than regulate”

holding companies. Meanwhile, on January 27, the Federal Trade Commission unveiled

a report and summary of its 6-year investigation. The report provided a long list of

potential reforms and stated that whether to abolish all holding companies or permit a

single tier of holding companies was a “policy decision” for Congress.

On February 6, 1935, Rayburn and Senator Wheeler introduced the

administration’s bill into the House and Senate, respectively. The bill, which most major

newspapers summarized in detail on February 7, required utility holding companies to

register with the SEC and gave the SEC regulatory authority over their financings as well

as acquisitions and dispositions. The bill also, however, contained what was soon

nicknamed the “death sentence” provision, Section 11. This gave the SEC the authority,

beginning in 1938, to require holding companies to divest any securities and property

necessary to reorganize the utility industry into geographically compact systems.

Immediately after January 1, 1940, the SEC was directed to make every registered

holding company engage is such dispositions, reorganizations, or dissolutions as

necessary to make it “cease to be a holding company.” Section 11 was even more severe

than suggested reforms that would have prohibited more than a single layer of holding

companies. Section 11 banned all holding companies.

Both the New York Times and the Washington Post referred to the bill as

“drastic.” It was immediately controversial. Utility managers argued that the bill was

both unconstitutional and potentially disastrous to investors. The fact that the Tennessee

Valley Authority and other publicly-owned utilities were exempt from the statute led

12

promptly to charges that the administration’s real purpose was to nationalize the utility

industry—a charge the chairman of the Federal Power Commission felt compelled to

deny. The press reported investor concerns that the bill, if enacted, would force holding

companies into fire-sale divestitures of operating companies, causing substantial losses to

the holding companies’ public investors. By March 2, the New York Times reported that

the bill had provoked “the greatest volume of criticism and objection evoked by any

proposed legislation in recent years” and stated that although Representative Rayburn

was confident it would pass the House, there was “some doubt that the Senate will accept

the measure in its present form.” President Roosevelt argued that the bill would cause no

investor losses because holding company investors would receive shares in sound

operating companies. He also charged that opposition to the bill did not originate with

investors, but instead with the utility industry’s behind-the-scenes lobbying effort.

In the House, the bill was assigned to a subcommittee of the Interstate Commerce

Committee. Testimony before the subcommittee, including that by a commissioner of the

SEC, was often skeptical of the death sentence provision. On April 23, the New York

Times reported that an “informal” vote of the subcommittee favored removing the death

sentence provision by a 14-11 margin. The subcommittee was ultimately unable to report

either favorably or unfavorably to the full committee.

The Senate Commerce Committee was also closely divided on whether to retain

the death sentence provision. On May 8, the Times reported that an informal poll of the

subcommittee favored removing the death sentence by a 9-6 margin. However, on the

same day an actual vote to delete the provision failed and the committee adopted a

13

compromise amendment that would merely delay the termination date for holding

companies from 1940 to 1942.

In early June, the New York Times reported that “informed” sources

acknowledged that the Roosevelt administration was prepared to compromise on the

death sentence provision in the face of “growing opposition” in Congress. A column by

the Times’ Washington correspondent Arthur Krock opined that it “seems certain that

important modifications” would be made to the bill. Senator Wheeler, however,

continued to insist on the death sentence provision, claiming to have received a letter

from the President urging passage of the bill with Section 11 intact. On June 11, the

Senate passed the amended bill including Section 11 by a 45-44 vote. The next day,

newspapers reported that the Senate action had halted a rally in holding company stocks.

On June 17, the House subcommittee approved the deletion of the death sentence

provision and “knowledgeable sources” told the press that the full Interstate Commerce

Committee would concur. Newspaper reports suggested that only when the bill went to

conference would the issue of the death sentence be resolved. A motion was made on the

House floor to reinstate Section 11. On July 2, the full House voted to reject the motion,

thereby assuring that the bill would pass the House, if at all, without the death sentence.

Arthur Krock called the vote a “major defeat” for the President.

By mid-July, the bill went to a House-Senate conference to reconcile the different

versions. Joseph Kennedy, the chairman of the SEC, urged the Senate Commerce

Committee to accept the House version. The press, meanwhile, reported that investor

fears of declines in utility stock and bond values were behind the House’s unusual

willingness to defy Roosevelt.

14

The Administration, however, took advantage of the lull leading up to the

conference to make its case that opposition to the death sentence provision was actually

the work of utility company lobbying. The House Rules Committee announced that it

would investigate lobbying by the utility industry. In mid-July, its investigation

uncovered evidence that a utility executive in Pennsylvania had sent hundreds of

telegrams to members of Congress ostensibly in the name of Pennsylvania residents.

This over-reaching appeared to change sentiment in Congress. For several days

in late July, the Senate heard testimony from residents of York, Pennsylvania whose

names had appeared on telegrams without their knowledge and from employees of the

local Western Union office who had transmitted the telegrams at the utility executive’s

request. Although the Pennsylvania incident appears to be isolated, it supported the

Administration’s longstanding position that opposition to its bill was contrived. The

Times opined at the end of July that the lobbying inquiry had strengthened the President’s

hand, making passage of the death sentence provision more likely.

On August 1, Representative Rayburn moved to instruct the House conferees to

acquiesce in the death sentence provision of the Senate bill. According to press reports,

the Administration concluded that after the lobbying revelations, the House would change

its stance. Rayburn and the Administration, however, miscalculated; the House voted

against the attempt. By mid-August, with the conference committee deadlocked, both

legislators and commentators suggested that the bill would have to be held over until the

next session.

Finally, in a meeting at the White House on Sunday, August 18, Senator Barkley

suggested the compromise language that ultimately resolved the differences among the

15

House, Senate, and Administration. The compromise provision permitted only one tier of

holding company atop any operating company and required that all of the operating

companies under a given holding company be either physically interconnected or capable

of such interconnection. The provision also gave the SEC the authority to grant

exemptions from this “single integrated system” requirement on a case-by-case basis.

On August 22, the President informed Representative Rayburn of his willingness

to accept the compromise and the House approved it. The text of the revised Section 11

was reprinted in full in the next day’s New York Times. After the close of trading on

August 23, the conference committee approved the compromise, as reported in the next

morning’s newspapers. Passage by the full House and Senate followed on Friday,

August 24, on Monday, August 26 the President signed the HCA into law.

Almost immediately, the electric utility industry’s industry association retained

John W. Davis, one of the country’s most prominent litigators, to bring a test case

challenging the constitutionality of the statute (Seligman 2003). The case, involving the

American States Public Service Company, was filed in federal district court in Baltimore.

On November 7, 1935, the district court found that the statute exceeded Congress’s

powers under the federal constitution and declared it “void in its entirety.” Although I

include the November 7 decision as an event below, there are two factors that likely

muted the market reaction to the decision. First, comments from the bench and rulings

on preliminary motions led observers to conclude that the court would declare the statute

unconstitutional, so the November 7 ruling was not wholly unanticipated. In addition,

lawyers must surely have viewed it as highly likely that the Supreme Court would

ultimately decide the Act’s constitutionality, so the district court ruling was only the first

16

step in a lengthy legal process. 1n 1938, the Supreme Court upheld the Act’s

constitutionality.

As this brief history demonstrates, there are a variety of dates in late 1934 through

late 1935 on which traders would almost certainly have revised up or down their

estimates of the likelihood that holding companies would have to relinquish their control

of their subsidiaries. I observe returns on both controlling and subsidiary companies on

those dates as described in more detail in the next section.

III. STUDY DESIGN

A. Data

I begin by identifying every company in the public utility industry (SIC two-digit

code 49) in the data files of the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) as of

January 1, 1935, a total of 23 companies. One of these is a foreign utility company cross-

listed on the NYSE, which I omit from the sample for two reasons. First, return data are

unavailable for many days. Second, it is unlikely that the expected return model I use for

U.S. utility companies would be valid for a cross-listed foreign company subject to

substantial risks stemming from events in its home country. Bonbright & Means (1932)

identify two other utility holding companies (United Corp. and Stone & Webster) that

have 2-digit SIC codes other than 49, and I add those to the sample, for a total of 24

NYSE-listed companies. To increase the sample size, I also hand-gather return data for

an additional 15 utility companies traded on the New York Curb Exchange. I identify

utility companies traded on the Curb based on company names and check that they are

covered by Moody’s Public Utilities manual. I omit utility companies for which a return

17

cannot be calculated for more than 50 of the 250 days in the estimation period. The final

sample consists of 39 utility companies.

Most of the sample firms are holding companies rather than operating companies.

Very few bottom-tier operating companies had a sufficiently large public float to be listed

on the NYSE or the Curb. Indeed, most of the operating companies were wholly-owned

or nearly wholly-owned by an intermediate-tier holding company. If the higher-tier

holding companies used their control to redistribute wealth from public investors,

therefore, these investors were found primarily in the intermediate-tier holding

companies. As a consequence, intermediate-tier holding companies serve as a convenient

proxy for their wholly-owned operating companies.

I therefore divide the sample into four categories, consisting of potential

“predators,” potential “prey,” companies that are both, and companies that are neither. I

define as predators companies that own a controlling stake, but less than 95%, of the

common stock of one or more subsidiary companies, as described more fully below. The

logic behind the definition is that there is no gain to be had from looting a wholly-owned

or almost wholly-owned subsidiary. In principle, the parent could extract wealth from

bondholders or other contractual creditors, but I assume that this is a less significant

problem because creditors can protect themselves through their contracts. Potential prey

are companies controlled but less than 95% owned by a predator. Some intermediate

holding companies meet both definitions—they have partially-owned subsidiaries and are

themselves partly-owned by a parent holding company. Others, primarily large urban

public utility systems like Brooklyn Union Gas and Southern California Edison, meet

neither definition—they are not controlled by a holding company and their subsidiaries, if

18

any, are wholly-owned. Such companies might be pyramids as a structural matter but

they could not have been designed to appropriate wealth from public shareholders of

subsidiary companies.

Because of the complex nature of some of the holding company pyramids, these

categorizations involve some arbitrary cut-offs. The most obvious is the 95% cut-off

identified above. Many holding company subsidiaries were almost, but not quite, 100%

owned. This was often a consequence of state corporate laws that required directors to

hold a minimum number of “qualifying shares” of the company. In other cases, at the

time of acquisition, the acquirer or target were barred by state law or by bond covenants

from engaging in a merger, with the result that the acquirer could only buy shares from

willing sellers. Thus, I treat ownership of 95% or more of a subsidiary’s common stock

as functionally equivalent to entire ownership. In addition, some holding companies

owned 95% or more of nearly all of their subsidiaries, but had a handful of very small

partly-owned subsidiaries. In many instances, these partly-owned subsidiaries were too

small to be a realistic source of rents for the holding company. To be categorized as a

predator, I therefore require that a holding company have partly-owned subsidiaries that

constitute in the aggregate at least 10%, by book value, of the parent company’s assets.

Finally, I define “control” of a company as (1) ownership of more than 10% of the

company’s common stock and (2) being the single largest shareholder. I use Moody’s

Investors Service (Moody's 1935), supplemented by Bonbright and Means (1932) and the

FTC Utility Report to classify companies. As an additional check, I obtain the names of

the directors of all the sample companies from Moody’s. All of the “predator”

companies in my sample have director overlaps with their “prey.”

19

Finally, it should be noted that a few of the holding companies identified as

having no parent company were more than 10% owned by an investment company. In

the pre-SEC era, investment companies could own a large stake in a portfolio company.

However, judging from the sources cited above, these investment companies were

passive investors and therefore not likely a “predator.” I can identify passive investment

companies because they are listed only in Moody’s Banking and Finance manual and not

the Public Utility manual.

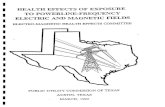

Figure 1 illustrates the categorizations just described by showing the ownership

pattern of one of the important holding company systems, the United Corporation system.

United was formed by J.P. Morgan & Co., its affiliate Drexel & Co., and its ally

Bonbright & Co. in 1929 to acquire control of smaller utility holding company systems.

In the diagram, United Corp. is a predator only. Although Morgan interests organized it

and underwrote all of its securities issues, the investment banks did not own a control

block. One might, however, argue that United Corp. was also Morgan’s “prey” because a

majority of its board of directors consisted of Morgan nominees designed in part to assure

that Morgan would be the lead manager for all of the company’s securities issues

(Commission 1943). As a check, I re-estimate all of the tests below after re-

characterizing United Corp. as both predator and prey. All results remain qualitatively

the same.

United’s partly-owned subsidiaries Columbia Gas & Electric Co., Niagara

Hudson Power Co. and Public Service Corp. of New Jersey are prey only. They are

controlled but less than 95% owned by United (including indirect ownership in the case

of Public Service Corp.). All of their subsidiaries are either 95% owned or too small to

20

constitute a plausible source of rents. United Gas Improvement Corp. (UGI), however, is

both predator and prey. United controls UGI through 26% stock ownership and

interlocking directors. However, UGI itself owns a controlling stake in Public Service

Corp. and Connecticut Electric Service Co. The latter company is not in my sample

because it is not traded on a major exchange and daily prices are therefore unavailable.

Table 1 lists the sample companies and their categorizations. It also identifies the

principal market on which the sample company’s common stock traded and its parent

company, if any. The table also shows the Moody’s rating for the largest debt issues of

each of the sample companies, which will be relevant to the cross-sectional analysis of

abnormal returns.

Daily returns for the NYSE-listed companies in the sample are taken from the

CRSP data. Daily returns for the Curb companies are calculated using CRSP’s

procedure—based on closing prices when available and on the midpoint of closing bid

and ask quotations when a stock does not trade on the relevant date.

I create four value-weighted portfolios consisting of predators that are not also

prey (n=7), companies that are both predators and prey (n=6), prey that are not also

predators (n=16), and “independent” companies that are neither predator nor prey (n=10).

I then calculate abnormal returns on each portfolio around the time of key legislative

events as described more fully below.

The null hypothesis is that the statute has no valuation effect. This would be so if

the effects of holding companies were small on average and traders did not expect the

costs of liquidating the holding companies to be substantial.

21

B. Test design

Using standard event-study technique (Brown & Warner 1985), I estimate a

market model for each of the four portfolios using 250 days of return data ending on

October 31, 1934. The first legislative event occurs on November 21, 1934. Because the

portfolios are value-weighted, I use the CRSP value-weighted index rather than the

equally-weighted index as the market proxy. I then measure abnormal returns around the

time of each event described in Table 2 except for Events 5 and 6 (May 7 and 8, 1935,

respectively). Because events favorable and unfavorable to the passage of the death

sentence provision occurred on succeeding days it is not possible to disentangle the

responses to the two events.

The presence of confounding events makes it essential to consider narrow event

windows. For example, on February 18, 1935, the Supreme Court decided the so-called

“Gold Clause Cases,” concerning the constitutionality of the government’s abrogation of

clauses in government and private debt requiring payment in gold (for a discussion see

Kroszner (2003)). The cases had dramatic implications for the value of both debt and

equity securities issued by most publicly traded companies—including utilities, which

had issued large amounts of bonds payable in gold. In most cases, therefore, I measure

abnormal returns for days 0 and 1 and also provide a cumulative total for the 2-day event

window. Day 0 is the day a legislative event occurred and day +1 is the day on which the

legislative action was reported in the press. I assess statistical significance using the time

series standard deviation of abnormal returns during the estimation period.

If, as their critics believed, pyramid structures were a means by which holding

companies extracted wealth from minority shareholders of subsidiary companies, the

HCA should have positive effects on prey and negative effects on predators. The “death

22

sentence” provision would damage the predator group by depriving them of the ability to

extract value from their prey. By the same logic, the death sentence provision should

benefit the prey group. Under this “rent extraction” hypothesis, therefore, we would

expect to see positive abnormal returns on the prey portfolio and negative abnormal

returns on the predator portfolio around the time of events favorable to passage of the

death sentence provision.

The prior literature offers an alternative hypothesis under which holding

companies added value to their subsidiaries by reducing financing costs. Presumably,

these cost savings were shared between (the shareholders of) the parent and subsidiary

companies. Dissolution of holding companies would destroy that value to the detriment

of both groups in relative amounts that would depend on how the surplus was split

between the parent and subsidiary companies. Even the independent companies,

although having public shareholders only at the top tier of the structure, were typically

organized in holding company form and faced being broken into smaller pieces. Under

this “efficient financing” hypothesis, then, banning pyramids would be detrimental to all

holding companies in the sample.

Unfortunately, we cannot easily distinguish this efficient financing hypothesis

from a different one sometimes mentioned by holding company critics—that holding

companies served primarily as a means to evade state rate regulation. Critics sometimes

argued that holding companies overcharged their subsidiaries as a means of inflating

costs, which were then passed on to the consumer through the typical rate-of-return style

state utility regulation (Hyman 1985). This hypothesis, although difficult to rule out,

faces at least one hurdle. As the public utility industry consolidated, rates fell

23

substantially (McDonald 1962). Of course, they may have fallen even more in the

absence of pyramid schemes, but at least on the surface there is no association between

pyramids and higher rates.

IV. RESULTS

A. Event study evidence: portfolio level

Table 3 reports abnormal returns for each of the four portfolios around the time of

the legislative events described above. One interesting initial observation is that

abnormal returns are economically and statistically large primarily on days of votes, not

on days on which the bill was introduced or on which key players stated their positions.

This is not very surprising—the administration clearly objected to holding companies and

traders presumably predicted that the bill would be somewhat punitive. However,

because the death sentence was highly controversial, it seems likely that traders could not

always have predicted the outcomes of votes, several of which were very close.

The sign of the abnormal return for the predator portfolio is as expected—

negative around the release of information suggesting a higher probability of the abolition

of some or all holding companies and positive around the release of information

suggesting a lower probability. The magnitudes are frequently large enough to be

statistically different from zero on at least one day around the time of key votes in

Congress.

Most important for current purposes, the predators and prey almost always move

in the same direction. On each of the nine individual days on which the abnormal return

on the predator portfolio is significantly different from zero, the abnormal return on the

prey portfolio has the same sign, and on seven of those it is statistically significant. The

24

“both predator and prey” portfolio also has abnormal returns of the same sign as those of

the predator and prey portfolios for each of those nine trading days, although they are

statistically significant on only five of the nine days. This effect is particularly

noteworthy for the April 23, July 2 and August 1 events, which were votes focused on the

death sentence provision rather than the entire bill. Traders appeared to believe that

passage of the “death sentence” provision would be bad for both predators and prey.

The “independent” portfolio has abnormal returns that are less reliably in line

with those of the other three portfolios. On eight of the nine dates on which the predator

portfolio has a significant nonzero abnormal return, the point estimate for the

independent portfolio has the same sign, but it is not always statistically significant. One

possible reason is that traders expected the independent companies to be able to comply

with the death sentence provision without forgoing the benefits of scale. The

independent companies often controlled fairly compact systems that could be merged or

put under a single holding company as permitted under the final version of the statute.

The evidence from this simple time-series test is more consistent with the efficient

financing hypothesis than the rent extraction hypothesis. It is noteworthy, however, that

the absolute value of the abnormal return is often smaller for the prey portfolio than for

the predator portfolio. This is not inconsistent with the financing hypothesis—it suggests

that the holding companies took a larger share of the surplus generated by their ability to

provide low-cost financing. But we cannot rule out that some rent extraction was

happening as well. It does, however, appear that any rent extraction was on a sufficiently

small scale to make the HCA a bad deal for prey as well as predators.

B. Cross-sectional evidence: firm-level

25

To try to shed more light on the effects of the HCA, I exploit firm-level

differences in abnormal returns. I begin by estimating a market model for each

individual stock in Portfolios A and B using the same methodology as that described

above. I then calculate average abnormal returns for each stock in those portfolios over

each of the event windows ending on April 24, June 12, July 3, August 2, August 27, and

November 8, 1935, constituting the event windows for which at least one of the predator

or prey portfolios experiences nonzero abnormal returns. By focusing only on event

windows on which traders reacted to news, I hope to reduce the amount of noise in the

estimates. I categorize each event as negative or positive from the perspective of

controlling companies, negative events being those that indicated a higher probability that

the death sentence would be enacted.

I then estimate the following regression:

1 2 3 4* *it t i i i t i t it

AAR Neg pred prey pred Neg prey Negα β β β β ε= + + + + + + (1)

where i indexes firms, t indexes dates, AAR is average abnormal return for the days in the

event window, pred and prey are indicator variables for predators and prey, respectively

(independent companies are the omitted class) and Neg indicates a negative event.

Coefficients β1 and β3 accordingly measure the mean difference between predatory firms

and independent firms around the time of positive and negative events, respectively.

Coefficients β2 and β4 measure the same for prey.

Table 4 reports estimated coefficients for the regression. Model 1 provides a

baseline that aggregates all firms together without omits all of the firm dummies. It

shows that the average firm in the sample earns an abnormal positive return of about

1.9% per day during event windows that include news unfavorable to passage of the

26

death sentence provision and about -4.7% on days on which there is news favorable to

passage. In Model 2, the sample is partitioned into predators, prey and independent

companies using the dummy variables. Some firms, as already described, are both

predator and prey. However, partitioning the sample further to distinguish those firms

that are only predators, only prey, or both does not change the results.

Model 2 shows that traders did not expect predators and prey to suffer by identical

amounts from the passage of the HCA. The results imply an average abnormal return of

-6.2% per day for predators and -4.4% per day for prey around the time of events

favorable to passage of the HCA. This is consistent with the evidence from the portfolio-

level analysis suggesting that abnormal returns on the predator portfolio are larger in

absolute value during the key event windows than those on the prey portfolio.

Nevertheless, it remains clear that traders believed that the HCA would destroy value for

both predators and prey.

As a robustness check, I also include fixed effects for holding company systems.

We might be particularly interested in how the returns on the predators and prey within a

particular holding company system compare. The fixed-effects regression (unreported)

produces the same result—predators and prey, on average, earn negative (positive)

abnormal returns around the time of events favorable (unfavorable) to passage of the

HCA, but the absolute values are greater for the predators.

The analysis so far, however, does not control for other relevant differences

among the sample firms. One obvious difference is that some of the sample firms are

healthy while others are in financial distress. This is particularly relevant because the

HCA would force holding companies to divest their utility holdings. For the most part,

27

holding companies owned controlling stakes in multiple subsidiaries and financed them

by borrowing at the holding company level. During the Depression, the value of the

subsidiaries decreased. In effect, then, the holding companies were analogous to the

holder of a call option. At some point in the future, their debts would mature. At that

point they could pay off their debts and retain ownership of the subsidiary companies or,

if the subsidiary companies were worth less than the amount of the debt, the holding

company could default and turn over ownership of the subsidiaries to their creditors.

Even those holding companies that owed more than the current value of their

subsidiaries, then, should have traded at positive prices so long as the holding company

could service its debt in the short run and there was some chance that the subsidiaries

would ultimately be worth more than the money owed.

By forcing prompt divestiture, however, the HCA extinguished this option value.

The holding companies lost the option to retain ownership of their subsidiaries while

waiting to see whether the Depression-related fall in the value of the subsidiaries would

end soon. This suggests that companies that were near financial distress had more to lose

from the HCA than companies on a sounder footing. The closer to bankruptcy a holding

company was, the more of its value would be represented by the call option on its

subsidiaries, and therefore the more value it would lose from divestiture.

To control for this effect, then, I search Moody’s Public Utility manuals to

determine the ratings on the sample companies’ outstanding bonds. I select the largest

publicly-traded debt issue for each holding company that has direct obligations. Some

top-tier holding companies concentrated their borrowings at the intermediate holding

company level. For these, I use the debt ratings on the companies consolidated

28

indebtedness as a proxy for its own debt rating. I treat all ratings of “A” or above as a

single category and all ratings of “B” or below as a single category. The ratings are

shown in Table 1.

Model 1 in Table 5 shows the results of a regression of average abnormal returns

during event windows on the debt rating of the company. Consistent with the prediction,

we see that the expected effects of the HCA are much worse for companies with poor

debt ratings than for those with strong ratings. Consider first the estimated coefficient on

the “negative event” variable. This measures the average abnormal return for negative

events on companies rated “B” or lower, which is the omitted category in the regression.

Compare this to the estimated coefficient on the interaction between “A” or higher rating

and negative event. This tells us that the average abnormal return during a negative event

window is -8.5% for the “B”-rated companies but -2.5% for the “A”-rated companies.

Companies with Baa and Ba ratings fall in the middle.

Model 2 adds in dummy variables for predators and prey. These variables take

some of the load from the debt ratings but the results remain consistent with that of

Model 1—highly-rated companies were expected to suffer relatively little from the HCA,

and controlling for debt rating both predators and prey experience negative abnormal

returns around event favorable to passage.

An alternative, unreported, approach is to ask a simpler question—is the company

part of a holding company system that is in financial distress? I take the top holding

company’s inability to pay preferred stock dividends as a simple proxy for financial

distress. If Moody’s reports that the holding company has missed preferred dividends, I

29

code every company within that holding company system as “distressed.” The results are

consistent with those reported using debt ratings.

C. Implications

Across a wide range of specifications, then, the same picture emerges. Traders

expected the HCA to destroy value for publicly-traded firms at all levels of the pyramid

structures. This is consistent with the view that holding company structures served to

economize on financing and other costs for the lower-tier companies. The lower-tier

companies suffer less than the higher-tier companies, suggesting that the benefits of the

structure were not shared equally at all levels, but instead were greater at the top. This

may reflect wealth extraction of a kind that researchers today call “tunneling” (Johnson et

al. 2000). Alternatively, it may reflect a less malign phenomenon—the top holding

companies may simply have taken a large share of the surplus that their own activities

generated for the lower-tier companies. In either event, however, the evidence from

mandated dissolution of the holding company pyramids suggests that they were

beneficial to the companies in them.

This result is not consistent with all studies of concentrated ownership. Indeed,

several studies find that using devices like pyramids to amass control rights in excess of

cash flow rights is detrimental to the other shareholders of the controlled companies

(Claessens et al. 1999; Faccio et al. 2001). We can reconcile the present results with

those in one of two ways. First, there is a growing recognition that firm-level and

country-level governance are to some extent substitutes. The background governance

rules in the U.S. (even in the 1930s) are generally favorable to shareholders. This may

have created space for firms to benefit from structures that, in a different institutional

30

environment, would have created an excessive risk of agency losses. A second factor that

may have limited the top tier companies’ ability to appropriate wealth from their

subsidiaries is the fact that the utility industry was hugely capital intensive. Because the

holding company systems had to go back to the capital markets on a frequent basis to

raise capital for companies at all levels of the pyramid, they could not afford a reputation

for being excessively rapacious.

V. CONCLUSION

The evidence from abnormal returns suggests that traders viewed the “death

sentence” provision of the HCA, which outlawed pyramid structures, as detrimental to

both the controlling companies at the top of the utility pyramids and to the controlled

companies in the lower tiers of the pyramids. The effects are most severe for holding

companies that were financially distressed. For these companies, liquidation would mean

loss of a continuation option and the consequent destruction of value. In all

specifications, lower-tier companies lose less from passage of the HCA, suggesting that

the top-tier companies benefited more from pyramiding than did the lower-tier

companies.

31

Attig, N., Fong, W.-M., Gadhoum, Y., Lang, L.H.P., 2004. Effects of Large Shareholding

on Information Asymmetry and Stock Liquidity.

Bonbright, J.C., Means, G.C., 1932. The Holding Company: Its Public Significance and

its Regulation. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York.

Brown, S.J., Warner, J.B., 1985. Using daily stock returns : The case of event studies.

Journal of Financial Economics 14, 3

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J., Lang, L.H.P., 1999. Expropriation of Minority

Shareholders in East Asia.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J., Lang, L.H.P., 2002. Disentangling the Incentive and

Entrenchment Effects of Large Shareholdings. Journal of Finance 57, 2741-2771

Commission, S.a.E., 1943. In the Matter of The United Corporation. In: SEC, p. 854.

Securities and Exchange Commission

Demsetz, H., 1968. Why Regulate Utilities? Journal of Law and Economics 11, 55-65

Demsetz, H., Lehn, K., 1985. The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and

consequences. Journal of Political Economy 93, 1155-1177

Durnev, A.R.T., Kim, E.H., 2005. To Steal or Not to Steal: Firm Attributes, Legal

Environment, and Valuation. The Journal of Finance 60, 1461-1493

Edwards, J.S.S., Weichenrieder, A.J., 2004. Ownership concentration and share

valuation. German Economic Review 5, 143-171

Faccio, M., Lang, L.H.P., Young, L., 2001. Dividends and Expropriation. American

Economic Review 91, 54-78

Gertner, R.H., Scharfstein, D.S., Stein, J.C., 1994. Internal Versus External Capital

Markets. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109, 1211-1230

Hausman, W.J., Neufeld, J.L., 2002. The Market for Capital and the Origins of State

Regulation of Electric Utilities in the United States. Journal of Economic History

62, 1050-1073

Holderness, C.G., Sheehan, D.P., 1988. The role of majority shareholders in publicly held

corporations : An exploratory analysis. Journal of Financial Economics 20, 317-

346

Hyman, L., 1985. America's electric utilities: past, present and future. Public Utilities

Reports, Inc., Arlington, VA.

Jarrell, G.A., 1978. Demand for State Regulation of the Electric Utility Industry. Journal

of Law and Economics 21, 269-295

Jensen, M., Meckling, W., 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs,

and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 11, 5-50

Johnson, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., 2000. Tunneling. American

Economic Review 90, 22-27

Kroszner, R.S., 2003. Is it Better to Forgive than to Receive? An Empirical Analysis of

the Impact of Debt Repudiation. NBER

McConnell, J.J., Servaes, H., 1990. Additional evidence on equity ownership and

corporate value. Journal of Financial Economics 27, 595-612

McDonald, F., 1962. Insull. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Moody's, 1935. Moody's Manual of Investments: Public Utility Securities. Moody's

Investors Service, Ltd., London.

32

Morck, R., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R.W., 1988. Management ownership and market

valuation : An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics 20, 293-315

Priest, G.L., 1993. The Origins of Utility Regulation and the "Theories of Regulation"

Debate. Journal of Law and Economics 36, 289-323

Seligman, J., 2003. The transformation of Wall Street : a history of the Securities and

Exchange Commission and modern corporate finance. Aspen Publishers, New

York.

Shleifer, A., Vishny, R., 1997. A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance 52,

737-783

Shleifer, A., Vishny, R., 1998. The Grabbing Hand: Government Pathologies and Their

Cures. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

33

Table 1. Sample firms.

Name Market Parent company Type Debt

rating

American & Foreign Power, Inc. NYSE Elec. Bond & Shr. Prey B

American Gas & Electric Co. Curb Elec. Bond & Shr. Prey A

American Light & Traction Co. Curb Unit. L. &Rwys* Prey A

American Power & Light Co. NYSE Elec. Bond & Shr. Prey Ba

American Water Works & Electric Co. NYSE Elec. Pwr. & Lt. Prey Ba

Arkansas Natural Gas Co. Curb Cities Service Prey n/a

Brooklyn Union Gas Co. NYSE None Neither A

Cities Service Co. Curb None Predator B

Columbia Gas & Electric Co. NYSE United Corp. Prey Baa

Commonwealth & Southern Corp. NYSE None Neither A

Commonwealth Edison Co. Curb None Predator A

Consolidated Gas, Electric Light &

Power Co. of Baltimore Curb None Neither A

Consolidated Gas Co. of NY NYSE None Neither A

Detroit Edison Co. NYSE North American Co Prey A

Duke Power Curb None Neither A

Electric Bond & Share Co. Curb None Predator Ba

Electric Power & Light Corp. NYSE Elec. Bond & Shr. Both B

Engineers Public Service Co. NYSE Stone & Webster Prey Baa

Federal Light & Traction Co. NYSE Cities Service Both Ba

Hackensack Water Co. NYSE None Neither A

Laclede Gas & Light Co. NYSE Utilities Pwr & Lt. Prey Ba

Long Island Lighting Co. Curb None Neither Baa

Memphis Natural Gas Co. Curb Commonwlth Gas* Prey Baa

National Power & Light Co. NYSE Elec. Bond & Shr. Prey Ba

Niagara Hudson Power Corp. Curb United Corp. Prey A

North American Co. NYSE None Predator Baa

Pacific Gas & Electric Co. NYSE North American Co Prey A

Pacific Lighting Corp. NYSE None Neither A

Peoples Gas Light & Coke Co. NYSE None Neither Baa

Public Service Corp. of NJ NYSE United Gas Imprvt. Prey A

Southern California Edison Co. NYSE None Neither A

Standard Gas & Electric Co. NYSE Standard Pwr & Lt. Both B

Standard Power & Light Corp. Curb U.S. Electric Pwr* Both B

Stone & Webster Inc. NYSE None Predator Baa

Tampa Electric Corp. Curb Stone & Webster Prey n/a

United Corp. NYSE None Predator A

United Gas Corp. Curb Elec. Pwr. & Lt. Both Baa

United Gas Improvement Co. NYSE United Corp. Both A

Utilities Power & Light Co. Curb None Predator B

34

Parent companies marked with an asterisk are not traded on the NYSE or Curb and

therefore not part of the sample.

35

Table 2. Description of legislative events

Event # Date Description Effect

1 11/21/1934 Rumor that Admin. bill will ban holding companies ↑ 2 1/11/1935 Rayburn speaks in favor of abolishing holding companies ↑ 3 2/6/1935 Rayburn-Wheeler bill introduced ↑ 4 4/23/1935 Informal House subcommittee vote against §11 ↓ 5 5/7/1935 Informal Senate committee vote against §11 ↓ 6 5/8/1935 Senate committee approves “death penalty” delay until

1942 ↑

7 6/11/1935 Senate passes bill with amended §11 ↑ 8 6/17/1935 House subcommittee votes to remove §11 ↓ 9 7/2/1935 House votes to remove §11 ↓ 10 8/1/1935 House rejects motion to reinstate §11 following lobbying

relevations ↓

11 8/22/1935* House approves Barkley compromise ↑ 12 8/23/1935* Conference committee approves Barkley compromise ↑ 13 8/24/1935 House and Senate pass HCA ↑ 14 8/26/1935 President signs HCA ↑ 15 11/7/1935 District court declares HCA unconstitutional in entirety ↓

* denotes an event known to have occurred after the close of trading

The column headed “effect” indicates by an up or down arrow whether the event

would have increased or decreased assessments of the probability of a partial or total

ban on utility holding companies.

36

Table 3. Abnormal returns around legislative events

Abnormal return in percent; t-statistics in parentheses

Date Predators Both predator

and prey

Prey Independent

0.93 2.33 1.41 1.07 Nov. 21, 1934

(0.62) (1.83) (1.34) (0.93)

-2.08 1.37 0.16 0.45 Nov. 21, 1934

(-1.39) (1.07) (0.15) (0.39)

-1.15 3.70* 1.57 1.51 2-day window

(-0.54) (2.05) (1.06) (0.93)

-0.50 -0.55 0.90 -0.34 Jan. 11, 1935

(-0.33) (-0.43) (0.85) (-0.30)

-1.66 -0.23 -1.57 0.45 Jan 12, 1935

(-1.11) (-0.18) (-1.49) (0.39)

-2.15 -0.78 -0.68 0.10 2-day window

(-1.02) (-0.43) (-0.45) (0.06)

0.28 -1.12 -0.54 -0.04 Feb. 6, 1935

(0.19) (-0.88) (-0.52) (-0.04)

-1.81 -0.92 -1.41 0.55 Feb 7, 1935

(-1.21) (-0.72) (-1.34) (0.48)

-1.53 -2.04 -1.95 0.50 2-day window

(-0.72) (-1.13) (-1.31) (0.31)

3.59* 4.01** 2.68* 2.09 April 23, 1935

(2.41) (3.14) (2.55) (1.83)

1.54 -1.51 1.68 2.81* April 24, 1935

(1.03) (-1.18) (1.59) (2.46)

5.13* 2.51 4.36* 4.90* 2-day window

(2.43) (1.39) (2.93) (3.03)

-0.99 -3.16* -0.34 3.19* June 11, 1935

(-0.66) (-2.47) (-0.32) (2.79)

-4.90** -5.28** -2.98** -3.05** June 12, 1935

(-3.28) (-4.13) (-2.83) (-2.66)

-5.88** -8.44** -3.32* 0.14 2-day window

(-2.79) (-4.67) (-2.23) 0.09

1.96 -0.40 2.79** 2.61* June 17, 1935

(1.32) (-0.31) (2.64) (2.28)

0.51 -0.36 0.37 -0.81 June 18, 1935

(0.34) (-0.28) (0.35) (-0.71)

2.47 -0.76 3.16* 1.80 2-day window

(1.17) (-0.42) (2.12) (1.11)

7.10** 1.96 2.45* 1.54 July 2, 1935

(4.75) (1.53) (2.32) (1.34)

July 3, 1935 1.85 2.41 0.87 0.96

37

(1.24) (1.88) (0.82) (0.84)

8.95** 4.36* 3.31* 2.50 2-day window

(4.24) (2.41) (2.22) (1.54)

0.33 -0.62 -0.78 -0.75 Aug. 1, 1935

(0.22) (-0.49) (-0.74) (-0.66)

4.47** 1.44 2.31* 1.32 Aug. 2, 1935

(3.00) (1.13) (2.19) (1.15)

4.80* 0.82 1.53 0.56 2-day window

(2.27) (0.45) (1.03) (0.35)

-0.08 2.01 -1.06 0.51 Aug. 22, 1935

(-0.05) (1.58) (-1.01) (0.44)

-7.45** -6.47** -2.99** -3.26** Aug. 23, 1935

(-4.99) (-5.06) (-2.84) (-2.85)

-8.41** -7.71** -3.84** -1.49 Aug 24, 1935

(-5.63) (-6.04) (-3.64) (-1.30)

6.60** -0.22 1.48 -0.12 Aug 26. 1935

(4.42) (-0.18) (1.41) (-0.10)

-4.55** -0.95 -3.30** -3.80** Aug. 27, 1935

(-3.05) (-0.74) (-3.13) (-3.32)

-13.88** -13.34** -9.71** -8.17** 5-day window

(-9.27) (-7.62) (-4.57) (-4.18)

-0.07 -0.95 0.11 -0.08 Nov. 7, 1935

(-0.05) (-0.74) (0.10) (-0.07)

5.82** 4.13** 2.04 4.19** Nov. 8, 1935

(3.90) (3.23) (1.94) (3.66)

5.74** 3.18 2.15 4.11* 2-day window

(2.72) (1.76) (1.44) (2.54)

38

Table 4

Model 1 Model 2

Constant 1.86**

(0.25)

1.18*

(0.49)

Negative event -4.71**

(0.27)

-1.67**

(0.50)

Predator 1.25

(0.96)

Prey -0.47*

(0.24)

Predator * negative event -4.52**

(1.04)

Prey * negative event -2.72**

(0.26)

Adjusted r-squared 0.31 0.39

n 234 234

** denotes significance at the 1% level. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered on

firms.

39

Table 5

Model 1 Model 2

Constant 2.69

(1.49)

1.99*

(1.22)

Negative event -8.51**

(1.49)

-4.84**

(1.29)

A or higher rating -1.44

(1.55)

-0.93

(1.28)

A or higher rating * negative event 6.00**

(1.56)

3.59**

(1.30)

Baa rating -0.87

(1.73)

-0.51

(1.57)

Baa rating * negative event 3.54*

(1.74)

1.88

(1.62)

Ba rating 0.10

(1.64)

1.31

(1.43)

Ba rating * negative event 0.70

(1.65)

-0.48

(1.51)

Predator 0.71

(0.52)

Predator * negative event -2.96**

(0.72)

Prey 0.16

(0.20)

Prey * negative event -1.81**

(2.16)

Adjusted r-squared 0.42 0.43

n 222 222

Figure 1.

Structure of the United Corporation utility holding company system. Companies described in the shaded boxes are not contained in

the sample. The principal trading market for the common stock of companies in the sample is also shown.

United Corp.

(NYSE)

United Gas

Improvement

Co.

(NYSE)

Columbia

Gas &

Electric Corp.

(NYSE)

41

subsidiaries

>95% owned;

3 small

subsidiaries

>70% owned

20.7% 26.1%

Connecticut

Electric

Service Co.

(OTC)

61.1%

13

subsidiaries

>95% owned;

5 small

subsidiaries

>50% owned

Public Service

Corp. of NJ

(NYSE)

17.9%

36.7%

15

subsidiaries

>95% owned;

Niagara

Hudson

Power Corp.

(Curb)

21.9%

14

subsidiaries

>95% owned;