The perfume handbook, Nigel Groom, Chapman & Hall, London, 1992. No. of pages x + 323, price $35.00....

-

Upload

roger-stevens -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

2

Transcript of The perfume handbook, Nigel Groom, Chapman & Hall, London, 1992. No. of pages x + 323, price $35.00....

124 BOOK REVIEWS

that does not lend itself to cross-referencing. For ex- ample, references no. 40 and 90 in Chapter 1 are repeated as references no. 88 and 29 respectively in Chapter 2.

In the first chapter (32 pages, 121 references) entitled ‘Structure-Sweetness Relationship’, the physiological mechanism of taste perception is briefly discussed. Various hypotheses linking sweetness to molecular structure have been proposed and discarded, the most successful being that of Shallenberger as extended by Kier. By the application of considerable ingenuity, the mechanism is applied to quantitative structure-activity relationships of other sweetener types and elaborated further in the succeeding two chapters under the relevant sweetener.

Chapter 2 (91 pages, 365 references) is entitled ‘Naturally Occurring Sweet Substances’. The division of sweet substances into natural and synthetic is inevit- ably blurred when, for example, a substance is derived from a naturally occurring substrate by chemical, en- zymic or microbial modification. While it would be pedantic and unhelpful to insist on a strict adherence to definition, the classification of sweeteners under these headings appears to be arbitrary. For example, the chlorodeoxy derivatives of sucrose are treated under sucrose a natural sweetener, even though they are synthetic. Although reference is made to the potential of 1 ’ ,4,6’-trichlorotrideoxyga~acrosucrose, regarded as the non-caloric high-intensity sweetener most closely approaching the ideal, no details of its synthesis, properties, or health and safety status are given. The treatment of saccharide sweeteners is overall very muddled, particularly when manufacturing technology is described. Errors, such as describing hydrolysed starch syrups as hydrogenated starch hydrolysates (HSH) and citing glucose and fructose syrups as ex- amples will be confusing to the uninformed reader.

Chapter 3 (85 pages, 306 references) entitled ‘Syn-

thetic Sweeteners’ covers the non-saccharide synthetic sweeteners, which include the widely used non-caloric sugar substitutes, saccharin, cyclamate, acesulfam-K and aspartame. In a lengthy discussion of the molecular features of dipeptides and related compounds associ- ated with sweetness, a notable omission is the dipep- tideamide alitame currently under evaluation as a stable alternative to aspartame.

The synthetic phenoxyalkanoic acids are sweetness suppressants, not mentioned despite their being per- mitted food additives.

In Chapter 4 (10 pages, 37 references) entitled ‘Multiple Sweeteners’, the concept of synergy between different sweeteners is briefly discussed. However, the inclusion of a table of relative sweetness of solutions of permitted sweeteners at different concentrations seems to ignore the exponential relationship between concen- tration and relative sweetness of a substance and does not allow for the synergistic interaction of different sweeteners.

In publishing the first English edition, the opportunity for updating and correcting the text has been missed. Apart from innumerable trivial spelling errors and, more importantly, errors and omissions of fact, the literature is only covered up to 1989, there being a mere six references to publications in that year and none more recent.

Notwithstanding the criticism to which the book is open, it provides a comprehensive compilation of infor- mation on sweeteners which does not exist elsewhere in one source of reference and is a valuable guide to the literature. It is to be hoped that in the next edition stricter editing will eliminate the errors which detract from the authority and clarity.

K. J. PARKER Reading, U K

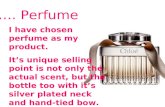

THE PERFUME HANDBOOK, Nigel Groom, Chapman &

f35.00. ISBN 0-412-46320-2. Hall, London, 1992. No. of pages x + 323, price

This book is essentially a dictionary listing perfumes, ancient and modern, their ingredients, creators, and manufacturers, and the containers designed to hold them. Under ‘P’ there are more detailed entries under perfume, perfume burner, perfume: care of, perfume: choice of, perfume: classification of fra- grances, perfume containers, perfume creation, per- fume families, perfume making at home, perfume manufacture, and perfume notes. Appendix A pro- vides a list of nearly 1400 fragrances with details of

the house that launched them and the year, together with a classification by family or brief description- those in bold type merit an entry in the main section of the book. Appendix B gives 74 recipes to illustrate the history of perfume making and to help people who wish to make fragrances at home. The book is concluded with a short bibliography (42 references).

In 1948 the author was a political officer in south- west Arabia which led to his earlier book Frankin- cense and Myrrh: A Srudy of rhe Arabian Incense Trade (1981). Accordingly the Handbook contains substantial entries on Arab, Egyptian, Greek and Roman perfumes. In order to make the book tech- nically acceptable, the author sought advice from the

BOOK REVIEWS 125

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, so we assume that the Latin names of the fragrant species are correct. However, the authorities for the Latin names are not given. If the author had taken similar advice from a chemist in one of the major flavour houses the value of the book would have been increased. This is parti- cularly true for the descriptions of pure substances, where a systematic name, or even a structure, would have been helpful. The book does not point out the complexity of essential oils-there is no mention of chromatography or gas chromatography-and the non-scientific reader may not readily distinguish be- tween complex essential oils and the individual sub- stances they contain. The entry on distillation could also be improved: the distinction between hydrodistil- lation and steam distillation is not clear. There is no mention of Clevenger’s apparatus or other oil stills. Terpene and sesquiterpene are not defined (no cross- reference to Chapman & Hall’s Dictionary of Terpe- noids) but there is an entry for terpeneless oils. Since the author is not a chemist it is perhaps unkind to

criticize his selection of terms, but these are the things a chemist may look for in the Handbook.

According to the preface, this book is for ‘the per- son with a general interest in the perfumes of modern times’. I am sure it measures up well to this criterion. Later the author states, ‘It is hoped that this work will go some way in reasserting the importance of the trained perfumer and reaffirming them as artists’. It is more difficult to assess how well this is achieved, but the entry on perfume creation goes some way to- wards it. It is the writer of the blurb on the back cover that claims it is ‘essential reading for perfu- miers’. This I doubt; I would expect a professional perfumer to be familiar with most of the material in this book. But his apprentice and those of us on the fringe of the perfume industry will find it a useful reference.

ROGER STEVENS Threlkeld

CULTIVATION AND PROCESSING OF MEDICINAL PLANTS, edited by L. Hornok, John Wiley, Chichester, 1992. No. of pages: 338, price f50.00. ISBN 0-471- 923883-4.

This book, which is a translation from the Hungarian book named Gyogynovenyek lermesztese es feldolgo- zasa, includes three major parts, written by eleven senior Hungarian researchers and top industrial leaders. The first part includes a general survey by the editor (L. Hornok) and chapters about heredity and variability, plant breeding and variety control (by P. Tetenyi), active substances (by D. Vagujfalvi), taxonomy (by A. Terpo), and environmental factors (by J. Bernath and L. Hornok) and concludes with a chapter about mech- anization during cultivation and the role of chemicals in the production process (by D. Foldesi and L. Hornok). Each chapter is followed by references, that are not up to date (beyond 1980).

The second part deals with 35 medicinal species from the Mediterranean basin and the third part with 23 miscellaneous species. For each species are presented

the characteristics, active ingredients, varieties, environmental requirements, cultivation conditions (sowing, nutrition, etc.), and harvest and post-harvest procedures.

Many species appearing in the book as medicinal plants could also be classified as aromatic plants. Therefore the title of the book could well be extended from ‘. . . Medicinal Plants’ to ‘. . . Medicinal and Aromatic Plants’.

The presentation of each chapter follows a logical sequence which is easy to read and understand. How- ever, although all chapters are of a high standard, it remains a Hungarian presentation, which in many cases is not suitable to conditions in other parts of the world. Nevertheless, this is a book that most people working with herbs and medicinal plants will need to consult.

E. PUTIEVSKY Newe Ya’ar, Agricultural Research Organization, Israel