The Lure of Antique Frames - The #1 Selling Antiques Magazine...frames also featured marine shapes...

Transcript of The Lure of Antique Frames - The #1 Selling Antiques Magazine...frames also featured marine shapes...

268 www.antiquesandfineart.com

Antique frames, in their seeminglyinfinite shapes and sizes, are beautiful mementos of bygone

days. Intricate designs evoke a time whencraftsmanship was an art in itself. Instead ofbeing diminished by the passage of time, frames,like fine wines, are enhanced by maturity. Ageseasons their color, adds character to theircomposition, and increases their value. Eventiny wormholes suggest that history has beenat work, marking the passage of time.

Yet the frame is the Cinderella of the artworld; beautiful, hardworking, and frequentlyoverlooked. The carefully-wrought creationsof previous centuries are at the mercy ofshifting tastes that can cause them to bereplaced, condemned to storage, or, worst ofall, destroyed. Few people, outside of a smallcircle of experts, are familiar with the long andvery colorful history of frames.

The wooden frame as we know it made itsdebut in the form of altarpieces in twelfth-century Italian churches and private chapels.

by Deborah Davis

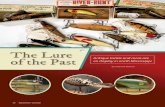

The Lure ofAntique Frames

PREVIOUS PAGE:Fig. 1: Carved and gilt mannerist frame of reverse

profile in the auricular style with stylized shell motifs

at centers surrounded by deeply sculpted scrolls and

volutes (detail). Italian, late-17th century.

33∆ x 24ƒ inches; W. 7 in. Courtesy of Lowy.

These large wooden panels displayed imagesof religious figures and were architectural inthat they often echoed the overall design ofthe church itself. Eventually, lighter and moreversatile frames began to appear in royal andaristocratic households. The fifteenth-centurytabernacle, or aedicular, frame kept the generalshape of its architecture-inspired antecedents,but was smaller and more portable. The cassetta (“little box”), or plate frame, whichwas very popular in Italy, was shaped like abox and easily moved; it was decorated or leftplain according to taste. The tondo frame wasround and usually decorated with a wreath ofcarved leaves.

Frame workshops flourished throughoutRenaissance Italy and the successful framerwas the equal of any artist. In fact, it was notunusual for a patron to engage a carver tobuild a substantial frame before an artist was

7th Anniversary Antiques & Fine Art 269

retained to create a painting for it. Leonardoda Vinci had to wait patiently for Italianmaster woodcarver Giacomo del Maino tofinish creating his masterpiece — a hand-crafted frame — before the great painter couldbegin work on one of his famous paintings,Virgin of the Rocks.1

In Europe, frame designs varied accordingto their country of origin. The auricular frame,containing shapes resembling ears or earlobes(Fig. 1), was inspired by the distinctive creations of Dutch silversmith Paul deLamerie, a seventeenth century craftsman whowas so intrigued by a series of anatomy lectureshe attended in Prague that he incorporatedcartilaginous forms into his work. Auricularframes also featured marine shapes such asshells, making them a favorite choice ofwealthy traders who lived in seaports. Theauricular frame made its debut in Italy in thelate seventeenth century, when CardinalLeopoldo de Medici selected it for his diversecollections of paintings, including portraits byRembrandt, Titian, and Caravaggio.

In seventeenth-century Holland, simple,unadorned frames rendered in dark woods(Fig. 2) became increasingly popular as thecountry became more Protestant and its decorative styles became more subdued. Inaddition, houses in the Netherlands weretaxed according to their frontage; the narrower the house, the lower the tax. Consequently, windows were oversizedand walls and floors were pale to maximizenatural light. Dark frames made of costlyebony and tortoiseshell looked ideal in thisenvironment.

In Spain, framemakers followed in the footsteps of their Italian neighbors. But eventhen Spanish frames had a drama and excitement all their own. Spain’s bold aestheticwas enhanced by influences from its SouthAmerican colonies, which contributed a mixture of exotic influences that resulted inframes that were vigorous and varied. Masks,flower head and leaf carvings, faux-leather

punchwork, and scrolling acanthus leaves are afew of the lively and dramatic designs displayed on Spanish frames. Spain reached itscultural peak in the seventeenth century andthe country’s framemakers were at the heightof their creativity at this time. Some of themost unusual Spanish frames were producedin the provinces, where designs were bold, colorful, and folksy (Fig. 3). Rarely understatedor demure, antique Spanish frames could becounted on to announce themselves with flairand braggadocio.

Europe’s golden age of frame-making commenced in France in the seventeenth century, when Paris became the artistic centerof the world. During this time, the FrenchCourt dictated le dernier cri in all matters ofstyle. The tastemakers responsible for establishing French supremacy were the“Louis,” a succession of high-wattage kingswho dominated international culture for overa hundred years.

One of Louis XIII’s (reigned 1610–1643)principal concerns was to keep French artists

in France when many traditionally went off toItaly, then the acknowledged capital of thearts. Louis XIII encouraged a new sense ofnationalism among his people, and thanks tohis efforts, French artists instead remained insitu. The frames made during his reign echoedthe elaborate baroque details found in Frencharchitecture and interior design of the period.Highly ornamented, they had continuouscarvings of foliage, including acanthus, oak,and laurel leaves, husks, and sprays of flowers,often accompanied by carved ribbons.

Organic ornamentation remained in stylewhen Louis XIV, the Sun King, ascended tothe throne in 1643. He headquartered hiscourt at Versailles, a sumptuous palace withbaroque décor and frames — heavy, ornate,and boldly carved, with pronounced cornerand center decoration — reflected themonarch’s pronounced appetite for opulence.As with other furnishings at Versailles, frame decorations often included carved and gildedfleur-de-lis and sunflowers in homage to theSun King.

With Louis XIV’s death in 1715, his successor, Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans, acted asregent for the young Louis XV until 1722.

Fig. 2: Carved and ebonized frame with various ripple

and basketweave moldings. Dutch, mid-17th century.

16¬ x 13 inches; W. 12 in. Courtesy of Lowy.

7th Anniversary270 www.antiquesandfineart.com

Fig. 3: Unusual carved, gilt, and polychrome

frame with extended centers containing shells

and painted masks connected to cherub heads

at corners and by stylized scrolling leaf carvings.

Spain, late-17th to early 18th century.

8˚ x 6ƒ inches; W. 5ƒ in. Courtesy of Lowy.

During this period known as la Régence thetaste in decorative arts was for a style that waslighter and more playful. While frames continued to emphasize corners and centerswith cartouches, shells, and other decorativeelements, they also incorporated empty spacesto balance the ornamentation.

After Louis XV began his reign the Régencestyle was replaced by the rococo (derived from

the French words rocaille, or rock, andcoquille, meaning shell). This new style,rooted in asymmetrical naturalistic detailing,produced frames that suggested liveliness and motion and were decorated with panelsscrolling or “sweeping” into corner and centerornaments. Framers charged separate fees fordecorations, adding costs for festoons, ribbons,masks, and other “extras.” One way to keep

the cost down was to substitute molded composition ornaments for carved wood asthe former could be produced quickly andinexpensively.

The last Louis, Louis XVI (1754–1793),and his queen, Marie Antoinette, ruled at atime when neoclassicism, a style based on theaesthetic principles of ancient Greek andRoman art, was coming into fashion.

7th Anniversary Antiques & Fine Art 271

Archeological excavation of the buried citiesof Herculaneum and Pompeii in Italy in the1730s had generated a fascination for theancient world. Frames produced in thesecond half of the eighteenth century wereinfluenced by classical architecture andexhibited thinner, more geometric shapesand simpler decorations. Their designsemphasized symmetry, reflecting a largerdesire among the French for balance andequality in every aspect of life.

France’s finest frames were produced bymaster craftsmen who signed their workwith stamps. In the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the furniture-making district inParis, carpenters (menuisiers ) and cabinet-makers (ebenistes ) built the frames, and“sculpteurs” carved them. The process ofbecoming a frame maker was arduousbecause the profession was controlled bypowerful guilds. Fees were high and thetraining was long and rigorous — it was notuncommon for an apprentice to spendeighteen years serving a master. Only JeanChérin and Etienne-Louis Infroit, two ofFrance’s greatest frame artisans, were registered as both menuisiers and sculpteurs,meaning they could build and carve theirframes (Figs. 4– 4A)

In the early nineteenth century, England

was the first country to be transformed bythe Industrial Revolution and the first placewhere artists rebelled against it.Woodworking machines mass-producedcheap, utilitarian moldings that could bequickly and easily embellished with compo-sition ornaments. The carvers who oncespent years perfecting their skills became adying breed. The Arts and Crafts and thePre-Raphaelite movements were born, inpart, to protest the forced obsolescence of

the craftsman. Artists like Dante GabrielRossetti and William Morris longed to goback to a time when objects were made byhand and promoted the art of craftsmanshipin their work and in the work of others.They were fascinated by visions of the colorful medieval world and created specialframes, often made of carved and gilded oakand rendered in the fifteenth-century

Fig. 4: One of a pair of frames by Jean Cherin, Paris, France, mid-18th century. (Detailed) Exquisitely carved example of transitional Louis XV-style gilt double sweep

frame ornamented with shell centers, acanthus fan corners, and top crested with a ribbon-tied leaf and flower cluster above a cabochon. 43 x 34© inches; W. 10 in.

Courtesy of Lowy. INSET: Fig. 4A: Detail of stamp on verso, “CHERIN.”

7th Anniversary272 www.antiquesandfineart.com

tabernacle style, to surround the poetic andfanciful images these figures inspired.

In the late nineteenth and early twen-tieth century, American frame makersbecame prominent. In 1891, architectStanford White designed his classic grilleframe (Fig. 5), a perfect complement to thepaintings of ar t ist Thomas WilmerDewing. Talented frame makers such asHermann Dudley Murphy, CharlesPrendergast, and Frederick Harer createdworks that proved Old World craftsman-ship was flourishing in the New World.

In modern times, after WW I through the

last quarter of the twentieth century, periodframes fell out of fashion and endured decadesof inattention and indignity. Many werestripped of their brilliant gold finishes, discarded, or relegated to the backrooms ofantique stores. The prevailing trend amongmuseums and collectors was to replace antiqueframes with sleek, minimalist edges.

But in the 1970s, period frames began toemerge from the shadows. Collectors, payingrecord prices for paintings, became more selec-tive in their choice of frames for their pricyacquisitions. Antique frames, consideredostentatious and old-fashioned in the 1950s

and 1960s, were suddenly just right in the1980s, partly because collectors knew enoughto appreciate them, and partly because, in thisgreed-is-good moment, buyers were not averseto displaying their wealth on the wall. Framescontinued to step out in high style in the1990s when they were the subject of exhibitionsat The Metropolitan Museum, The ArtInstitute of Chicago, and the Bagatelle inParis. They became coveted at auction; oneyear, French antique frames commanded thehighest prices, while the next year, Spanishframes moved into first place. Prices soared toa record high in 1991, when a seventeenth-

Fig. 5: Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Lady inLavender, circa 1910, with a Stanford White grille

frame, circa 1890. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of

Filipacchi publishing; photography by Gerardo

Somoza, .

Figs. 6–7: The right antique frame can bring a painting to life. This highly gilded finish (Fig. 6, top) is too

much of a contrast to the softer palette of John Singer Sargent’s Rosina—Capri (1878, oil on canvas), and

the frame is too static and confining for a painting with so much movement. However, Sargent’s lively

Mediterranean subject is beautifully complimented by a more decorative gilt and polychrome frame from

the same region (Fig. 7, bottom). The frame’s expressive design reinforces the kinetic energy of the painting

while its soft patina blends perfectly with Sargent’s subtle grey tones. Courtesy of Lowy.

7th Anniversary Antiques & Fine Art 273

century carved amber mirror frame sold foralmost a million dollars at Sotheby’s inLondon. Today these neglected treasures ofbygone days are back in all their splendor andonce again in the spotlight (Fig. 6, 7).

One of the early twentieth century connoisseurs of antique frames was Hilly Sharof Julius Lowy Frame and RestoringCompany, Inc. in New York. Shar’s collectionof frames ranged from Italian, French, andSpanish examples to Dutch and Americanmasterworks. For the past 100 years, the firmhas preserved and promoted antique andauthentic reproduction frames, and in celebration of the company’s centennial, theyhave published The Secret Lives of Frames:One Hundred Years of Art and Artistry(Filipacchi, January 2007, $50.00). While thestory of Lowy, the facets of frame making,proper fitting techniques, and even how toinspect for originality, are discussed, themajority of the book is devoted to a survey ofthe frame’s evolution. For more information,visit www.lowyonline.com.

Deborah Davis is author of The SecretLives of Frames. She is known for her best-selling books Strapless: John SingerSargent and the Fall of Madame X andParty of the Century: The Fabulous Storyof Truman Capote and His Black andWhite Ball.

1 Grimm, Claus, The Book of Picture Frames (Abaris Books,New York) 1992.