The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

Transcript of The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 1/12

ROCK ART RESEARCHThe Journal of the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA)

and of the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO)

ISSN 0813~0426

Volume 26, Number 2

Melbourne, Australia

November 2009

The Board of Editorial Advisers:

Professor John B. Campbell (Australia), Professor Chen Zhao Fu (China),

John Clegg (Australia), Mario Cousens (Uruguay), Dr Bruno David (Australia),

Professor Paul Faulstich (U.S.A.), Dr Josephine Flood (AustraIia/U.K.), R. G. Gunn

(Australia), Professor Mike J . Marwood (Australia), Dr Yann-Pierre Montelle

(New Zealand), Professor Roy Querejazu Lewis (Bolivia), Pamela M. Russell (New

Zealand), Professor Daria Seglie (Italy), Dr Claire Smith (Australia), Professor B.K.

Swartz, [r (U.S.A.), Dr Graeme K.Ward (Australia).

Founding Editor: Robert G. Bednarik

The princi palobjectives of the Australian Rock Art Research Association are to provide

a forum for the dissemination of research findings; to promote Aboriginal custodianship

of sites externalising traditional Australian culture; to co-ordinate studies concerning

the significance, distribution and conservation of rock art, both nationally and with

individuals and organisations abroad; and to generally promote awareness and

appreciation of Australia's pre-Historic cultural heritage.

Archaeological Publications, Melbourne

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 2/12

RockArt Re.searc" 2009 - Volume 26, Number 2, / 'P. 213-223. C. 1:.ECHEVARRiA L. oud Z. VALENCIA G. 213

KEYWORDS: Llama - Rock art - Architecture - CUSCO empire- Tahuantinsuyu - Peru

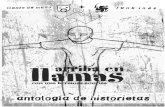

THE iLLAMAS' FROM CHOQUEQUIRAO:

A 15TH-CENTURY CUSCO IMPERIAL ROCK ART

Gori Tumi EchevarrIa L6pez and Zenobia Valencia Garda

Abstract. Asystematic exploration of the archaeological site Choquequirao, Cusco, Peru, has

in 2004resulted inthe finding ofa group of semi-naturalistic and geometric motifs that were

created with natural stones in a series of terraces at this important site, a settlement located

next to the Apurimac river in the Amazonian - Andean limit of the mountain range of the

Andes. This finding opened the possibility of developing a comprehensive and controlled

investigation of these archaeological materials, which was developed in2005. Part of the

analyses carried out included technical approaches of these features as well as historical

correlations. This paper presents an analysis of the semi-naturalistic figures, stressing the

proposition of the artistic nature, and the cultural and chronological association of these

motifs.

Introduction

In 2004, thanks to the project 'Cadastre and

Delimitation of the Choquequirao Archaeological

Park', financed by the institution COPESCO National,

one of the most notable finds of Peruvian archaeology

took place. A series of figures of camelids elaborated

in white stones were found in a group of terraces in

one sector of the archaeological site Choquequirao,

which is a 15th and 16th century settlement associated

with the Andean, empire called Tahuantinsuyu. These

findings were officially reported to the National Cui ture

Institute (INC) of Peru in 2004 (Valencia 2005; Karp

2005), and in2005 the 'Archaeological and Historical

Research Project of Choquequirao's Sector VIII

- Las Llamas' was planned and executed. Both the

discovery and the investigation were dir-ected by the

archaeologist Zenohio Valencia from the University

San Antonio Abad of Cusco,

During the' project's fieldwork the archaeologist

Gori Tumi Echevarria L6pez from San Marcos Uni-

versity joined the research to design the specialised

strategy for the study of the discovered images. Si-

multaneously with the rock art analysis the project

developed diverse investigations, including thestudy of the twelve architectural sectors of the site, the

study of the sector VIII terrace structure, the study of

the system of channels related to the terraces, among

The authors dedica te this paper to the m em ory of

C us co a rc ha eo lo gis t P ro fe ss or L uis B ar re da M u rillo .

others. Different data obtained by these works are

reported in this article to propose the archaeological

context of this important and new evidence of

Andean palaeoart.

About rock art terminology

As it will be seen below, this is a new type of

cultural expression made of natural rock, whose physi-

cal nature differs from the classical definition ofrock

art' (Bednarik 2007: 7,209). Although the terminology

recognises variations inthe typological divisions of

rock art (petroglyphs, paintings, portable palaeoart and

two types of geoglyphs) by two principal processes,

addi tive and reductive, there is no reason not to accept

the kind of rock imagery described here as 'rock art'

s ens u la io, especially in consideration of the additive

process involved in the fabric, and this is consistent

with the consideration of geoglyphs as rock art in the

same sense. The architectonical support is not a new

feature for palaeoart, as we can see in archaeological

sites such as Tzintzuntzan inMichoacan, Mexico, or

even in Cusco (Echevarria 2009), but it is the first time

it is recorded and studied in a structural frame. In

the region's native language this phenomenon can becalled quilcapirca (which could be translated as 'rock

art on wall').

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 3/12

2.14 Rock Ar t Research 2009 - Vol""," 26 , NHm/,,.,. 2. 1 ' 1 ' . 213-223. G . T EO tt:V AR Rf A L " , , < I Z. VALENCIA G .

• Andahoayla.

o 40Km... Archaeoloqical site _ Actual town

. .Cusco

Figure 1. M a p o f lo ca tio n o f C ho qu eq uira o in th e C usc o re gio na l a re a.

Location

Choquequirao is located in the lower half of the

Apurimac river basin, on its right margin, appro~

ximately 1500 m above the riverbed level and 3100 m

above sea level.111ezone inwhich the site islocated

corresponds tothe 'Amazonia quechua' (Pulgar 1946)

or 'Andean Amazonia' (Morales 1993: 621) natural

region, characterised by a mountainous topography

covered by flora and fauna ofAmazonian type. TIlls

location constitutes theecologicalboundary between

the birth oftheAmazon in the mountain ranges ofthe

eastern slope oftheAndes, and the high mountainous

semi-desert region of the Andes (Fig. 1).

The archaeological site is on an elevated spur of

a mountain range that borders the Apurimac river

directly. The central area of the site was levelled

artificially to place the principal infrastructure of

the settlement (Fig.2), and the surrounding hillsides

were terraced in great extensions to incorporate new

cultivation land and small residential areas. Sector

vrn of Choquequirao, where the rock art is located,

is a zone of terraces of cultivation on a mountain

slope whose terrace walls served as support for

the realisation of the naturalistic images and other

Figure 2. C en tr al a re a o f C ho qu eq uim o w ith e xp os ed m on um en ta l a rc hite ctu re .

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 4/12

Rock Art Research 2009 - Volllme 26, Number 1, pp . 213-223. C. T. ECHEVARRiA L. l ind Z. VALENCIA G .

Figure 3. P an ora mic view o f th e se cto r VIII of

Choquequ i r ao .

associated motifs (Fig. 3).

Methodology and research

Most of the discovered figures presented an

excellent state of preservation and the images or their

physical structures were almost unaffected, and it

was not necessary to manipulate any of the material.

This fact limited intervention to a study by simple

observation forwhich someofthe common parameters

applied to the archaeological analysis ofartefacts were

used, emphasising the selectionofmeasurable physical

variables for controlled comparisons. These variables

included well-known categories such as the f o rm , the

technique or the scale of the images. This approach

allowed the proposition of a hypothesis, by logical

argument, about some basic questions on the cultural

association or the contemporaneity of the motifs. Some

other questions, such as the chronological situation of

this rock art inPeruvian history, were solved bymeans

ofcross-studies that included archaeological analyses

and complementary historica 1references.

Following these premises we documented twenty-

five semi-naturalistic figures on the walls of the

terraces that are part of the half section of the sector

VITIof Choquequirao. The analysis exposes relevantresults for the establishment of a cultural articulation

context, as detailed below.

215

Figure 4. Mot i fS. (All s c al es in 10-011 units .)

Analysis and results

T e ch n iq u e o f p r od u cti on

The twenty-five figures were found on a uniformphysical support: retaining walls made of dry-laid

stones. These figures constituted part of the structure

of the walls, forming images by the contrast between

the type of rock used to delineate the image and the

type o f rock used to constitute the regular structure

of the same wall. This particularity is crucial in the

configuration ofall the structures in that the rocks that

form the images share the load ofthe edification that

serves as their support; therefore these are structural

image s . The type ofrock used in the wall isa dark schist

while the images are exclusively ofwhite calcocuarci ia ,

a sandstone of quartz and carbonate (Fig. 4).AJthough the figures are incorporated in the wall

structures, the stones used in these images do not

present the same phvsica Iqualities of the other stones

of the walls. Thus the contrast creating the imagery

isbasically provided by the variation in the colour of

the rock. No motif repeats the technicaJ design, in the

. number of blocks used to achieve the image or in the

particular arrangement of the blocks that configure

the image of the motif (Fig. 5, compare with Fig. 4).

This type of treatment individualises the figures in

a structure that does not repeat mechanically the

disposition ofits constituent elements, and this is one

ofthe technical reasons that allowed the production of

the motifs in the facades of these terraces. All the raw

material used in the construction ofthewallsand motifs

islocal and was obtained from quarries existing in the

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 5/12

216 Rock Art Besearch ZOO9 - Volume 26, Number 2, pp . 213-223. C. 1: ECHEVARRiA L and z. VALENCIA G.

Figure 5.. Mo tif 4 .

rocky outcrops of the sector VIII mountain

slope and in near hillsides (Echevarria

and Valencia 2008: 72). This indicates

evidently that the technical question of the

manufacture of the structures and figures

was solved locally and has depended on

the availability of the lithic material in

the zone.

TIle support a nd t he s c al e

In all the cases the motif support

is a simple retaining wall. The whole

archaeological area of sector VIII is

characterised exclusively by terraces for

cultivation. Although there are some

structural differences, in the building

design of the terrace walls or inthe use of

the construction material (Echevarria andValencia op. cit.), all the terraces that were

used to support figures constitute singular

construction units.

The wall structure presents an adjust-

ment of schist rocks of irregular fracture

placed vertica lly in a wedge fashion,

with the widest part towards the facade

of the wall (Fig. 6). Being irregular, these

stone blocks were adjusted mutually

while they were introduced in the wall

against the earthen filling of the terrace.

The same happened with the rocks that

form the figures. This kind of structure

covers the whole extent of the terraces,

of varied dimensions, with some sections

Figure 6 . W all with a structure o f sc his t r oc ks o f ir re gu la r form s,

sec tor VIlI.

and with all the comers built inmore uniform schist rocks placed

horizontally.

Although the figures occupy only a small part of the walls,

their scale depends dearly on their support, which is why there

are no figures of natural size. The came lid motifs vary between

a maximum height of 1.94 m and one minimum of 1.25 m, being

located ina central section of the wall. In some cases the figures'

size is limited by margins of the wall or by the surface floor of the

lower terrace (Fig. 7, compare with Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). The referential

location of the figures indicates a representative convention in

respect to its support and scale, a convention broken by the only

anthropomorphous figuration, of 1.20 m height, that does not

keep a proportion to its support, being located in the middle of

the wall.

Figure 7. G ene ra l loc ation o f the im age in its s upport, m otif 20 .

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 6/12

Rock Art Researd, 2009 - Volume 26,. Number 2, pp . 213-22.3. G. T: ECHEVARR iA L. an d Z. VALENCIA G.

Figure 8. A nih ro pom or ph ou s figu re , m otif 25.

Fo rma l v a ri a ti on

There are only two forms among all the figures

present onthese terraces,semi-naturalistic zoomorphic

figures (seeFigs4,5 and 7) and one anthropomorphous

figure (Fig. 8); for twenty-five motifs this distinction

implies a low representative formal variation. All

twenty-four zoomorphic figures belong to the same

type, indicating !:hatthisgroup was based on apremise

of uniform representation. The basic zoomorphic

figure is a simple composition achieved by three

straigh t lines: the lineof the neck and front leg,the line

oftheback, and the lineoftheback leg (Fig.9),and this

is the key concept ofthe form. Fora casual observer the

figures would constitute schematic repetitions, if the

main details associated to this outline that complement

the figures are not considered; these details are the

heads, the hooves and the tails.

Although the basic form is repeated as a scheme,

all the figures present independent compositions, in

their dimensions, in the number ofrocks used in theirmanufacture, or in the regular disposition of their

lines - which individualises the images according

to their production. Some elements of this formal

variation, like the difference in the position of the

legs (Table 1), have been diagnostic for a distinction

ofthe kind ofrepresentation implied by these variants

that indicate naturalistic attitudes. In the case of the

anthropomorphous figure (Fig. 8), it is evident that

the form is a pure geometric outline, since it does not

include any additional details to the depiction of the

human body, which differentiates this motif from the

zoomorphic ones.

S ty li st ic v a ri a ti on

Though the outlined shape ofthe animal constitutes

217

Figure 9. M otif 17 .

the base of the figuration, the details incorporated

into the images individualise the basic depiction,

endowing it with a notable naturalism. These details

appear asstylistic variations of the representation and

include the incorporation offacial details ofthe head,

with or without ears (Fig.10),the tail (Fig.II) and the

hooves (Fig.12).Additionalto these corporal elements,

objects resembling headdresses (Fig.13),necklaces or

MotifPosition of the hind legs

High Low Even

1 - X -2

- X -3 - X -4 - X -5 - X -6 X - -7 - X -8 - X -9 - X -

10 - X -11 X - -12 - X -13 - X -

14 - X -15 _ . X -

16 - - X

17 X - -

18 - X -

19 - X -20 - X -21 - X -22 - X -23 - X -24 - X -

Total 3 19 1

Table 1. Va ria tion in the position of the h ind le gs in . the

z oomor ph ic m o ti fs .

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 7/12

218 Rock Art Research. 20()9 - Volume 26, Number 2, r ' P - 213-223_ G_ T_ ECHEVARRiA L. and Z. VALENCIA C.

F ig ur e 1 0. H ea d w ith fa ci.a lfe atu re s

a n d e a rs , m o tif2 1.

Figure 11. Ta i l, mo t i fS . Figure 12. Hoof , m o ti f 4.

Figure 13. Head with 'h ea dd re ss ' a n d e a rs ,

mot i f 22.

scarves, and loads can also be recognised.

These details are adequately explicit as to Figure 14. 'A du lt lla m a ' with 'y o un .g ll am a ', m o tif s 8 a nd 9.

be able to establish the zoological nature of

the representations as llamas (L am a g lam a ), allowing

in addition to define the deliberate intention of the

authors to represent the animal in an individual and

unique manner, even in an. adult or youthful state

(Fig. 14).

The naturalistic figuration, in its details, describes

the particular variations of some cuitura[ attributes

of the llamas, using not only characteristics such as

presumed loads or headdresses. It is the depiction of

physical corporal variation of the animal (Table2)that

stands out, exposing with accuracy certain aspects ofthe behaviour of llamas. These aspects are especially

evident in the compared variation of these physical

details: in the dimensions and shapes of the llama

heads; in the presence and location of the ears; in the

position of the taiIs;or in the particular position ofthe

hooves, which may imply the graphic description of

movement.

The animal's movement, like a figurative attribute,

stands out especially in the graphical description

of the hooves' position (Fig. 15). They are oriented,

relative to its horizontal projection, downwards or

upwards, being different between the legsin the same'llama' and in every single 'llama'. This appears to be

a stylisticvariant complementary to the formal variant

qualifying the position of the legs (seeTable1),made

MotifsFeatures

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 81 X - ? X X - - -2 X - ? X , X _ . - -3 X X X X X - X X

4 X _ . ? X X - - X?

5 X X - X X - - -

6 X X X X X - - -7 X - X X X - X X?

8 X X? ? X X - - -9 X X X X X - - -

10 - - - X X - - -11 X X X X X - - -12 X X? X X X - X -13 X - X X - - X X

14 X X? X X X - X -

15 X - X X X - X -

16 X - X X X X? - -17 X - X X X - - -18 X X X X X - - X

19 X - X X X - - -

20 X X? X X X - - -21 X X X X X - - -22 X X X X X X - -23 X X X X X - - -24 X - - - X - - -25 - - - - - - - -

Table 2. Va ri at io n a n d d is tr ib u tio n o f s ty lis tic f ea tu r es :

1 - head , 2 - facia! f ea tures , 3 - ea r s , 4 - tai l , S - hoo],

6 - 'headdress', 7 - 'necklace', 8 - ' load' ,

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 8/12

R ock Ar t R e se a rc h 2009 - VO /"" l<126, Numbe r 2, pp . 213-223. G_ T. r;CHEVARRiA Land Z_ VALENCIA C.

deliberately to describe movement and

specifically to indicate marching animals.

The llamas' express, by means of their

technical production and in particular

by means of the incorporation of careful

stylistic details, a 'dynamic attitude'

(Echevarria 2008: 37).

O rg an is atio n a nd vis ua l p er sp ec tive

According to certain representative

parameters, explained below, the 'llamas'

have been graphically elaborated in

individual form or in groups of two,

three and even four motifs. The largest

motif percentage, fourteen 'llamas',

constitutes isolated figures on single

terrace walls (72% of the total), while

two terraces each show two spatially

associated llamas', presumed to be adult

with young (see Fig. 14) (11% of the total).

All the other figures, found in groups of

three and four 'Ilamas', inaddition to the

anthropomorphous figure, are located on

single terrace walls.

Ina group view the figures present an

ascending diagonal and linear placing,

following the progression of the terraces

tha t serve them as support, being located

almost at the edge of the mountainous

spur that emphasises the topography of

this sector. This location allows the group

of images to stand out within the entirearchitectural structure, implying that the

location was a deliberate choice (Fig. 16).

A remarkable detail of this arrangement

is that the figures are aligned in the

direction of the magnetic east, forming

two continuous parallel columns. The

column on the left, with ten 'llamas',

one on each successive terrace in linear

formation: and the co1umn on the right

where the fifteen remaining 'llamas' form

a more compact troop and where the

groups of two, three and four 'llamas' arelocated (Fig. 17). An individual 'llama'

was placed at the top of the group, and

at the base the anthropomorphous figure

follows the departure of the indi vidua 1

line of 'llamas'.

The relative placement of the figures

suggests that a group is naturalistically

represented on this scale. In addition

to the stylistic and formal details, the

individual motifs were produced in

two physical planes, apparently with

the intention to integrate them into a

major composition in order to describe a

complex scene that can be interpreted as

a pack of llamas on the march. This scene

219

Figure 15. MOhf18, i llu st ra ti ng h oo ve s p os it io n.

Figure 16. P an or am ic vie w o f the 'lla ma s', s ec to r V lll o f C ha ou eq uir ao .

Se e b ac k pa ge fo r c olou r ve rs ion .

Figure 17. P anor am ic vie w of the uppe r group of lla ma s.

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 9/12

220 Rock Art Research 2009 - Voillme26, Number 2, "".213·223.. G.T. ECHEVJtRRtA Land Z. VALENCIA C.

Figure 19. Wa ll w ith a s tr uc tu re o f s ch ist r oc ks o f r eg ula r jo rms,sec tor VITI.igure 18. Kero, va se o f wo od

w ith s ch em atic . figu re s of l l amas ,

a pp ro xim ate ly 2 0 e m height. Taken

from the co ve r of th e Journal of

the Museum and Archaeological

Institute of Cusco, No. 21,1967.

can be seen and recognised from the close mountain

slopes to the north of the terraces, suggesting that the

representation is a uniform design for an orientated

observation, and this should be considered as a

deliberate attribute of the design.

Discussion

The artist ic nature o f th e 's c en e '

The variables used in this analysis indicate that

the figurative elements in this terrace sector of

Choquequirao have been designed to constitute. an

integrated naturalistic scene whose vision implies

a perspective of depth - a feature not before docu-

mented for any sample of Andean art, of any period.

Additionally the naturalism imposed on the individual

motifs and on the whole group constitutes a novel

aspect in the history of-the art of Cusco, especially in

its imperial phase, that had not been recognised before.

It is clear then thatthe 'scene of marching llamas' is a

s ui g en e ris sample of Andean graphic expression.

The individual and scenic naturalism of the

Choquequirao's llamas reflects visual. reality. The

organisational relation implied by the apparent scene

can be seen today, because llamas (domesticated.

approximately 6000 years RC.E.; Altamirano 1993)

when marching in formation form compact packs

commanded by a dominant llama, followed by

grouped llamas, Barnas with young and individual

llamas; which is about the same arrangement as the

representation described (see Fig 16). Additionally theentire group is 'directed' by an anthropomorphous

figure that can be interpreted as a shepherd (namero)

driving the llamas (see Fig. 8).

The value of this apparent scene has implications

in considering the representational parameters

for the imperial Cusco art that are based on more

schematic forms derived from recognition on other

supports, like textiles, ceramics, stone or wood (Fig

18). Nevertheless, it is clear that this example exceeds

the flat manifestations of such other representative

art, indicating an explicit naturalism and a visual

perspective in three dimensions. This discovery opens

a new view for the understanding of the more classicalCusco art, as one of its more extended icons.

The structural concept for the construction of

the "llama' motif is also a remarkable aspect of these

images, especially because it does not compare with

the schema ticvalue of the rigorously structural figures

documented, for example, inthe Andean textiles (Fung

2004: 226). They depend, like the images that we are

studying, on their support to be able to achieve the

figurative effect of the image. The type of structure

that supports and constitutes the Choquequirao

'llama' figures does not depend on rigid geometric

tendencies, but on the flexibility of accommodating

the mosaic components in a non-linear stonewall.

This characteristic differen hates the structure of these

walls from any other wall formed by more uniform

materials, and with structures not achieved by forced

adjustment (Fig. 19).

No graphic representations exist in the archaeologi-

cal record of Peru that have used parameters of

technical elaboration similar to this work. This is

interesting because Andean mural art, using stone,

mud or painting, is common and extends to all Peru-

vian territory and in all its cultural periods tha t include

architecture, at least from 3000 years B.C.E. onwards.

Examples of decorated facades can be found inbuildings of cultures like those of La Galgada of 3000

years B.C.E. (Grieder and Bueno 1988: 48); Sechin of

1500 years B.C.E. (Bueno 1970-1971: 208; Samaniego

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 10/12

Rock Art Research 2009 - Volume 26, NumberZ, pp.213-223. G. T_ECHEVARRiA L and Z. VALENOA C. 221

(e ) COPESCO NACIONAl2005o 500m

F ig ur e 2 0. Map of the a rc ha eo logic al se ttle me nt o f C hoque quir ao showing the m ain se ctors m entione d in the te xt.

et a1. 1985: 168); Chavin of 1000 years B.C.E. (Tello

1929); Meche of 200 C.E. (Shaedel 1951); and later

in Pachacamac (Bueno 1983: 6), Chincha (Kauffman1973: 457) and Chachapoyas (Bonavia 1968: 90, Photo

6); and even in Tahuantinsuyu sites such as Tambo

Colorado or Paramonga (Kauffman op. cit.), among

others. All these examples of figurative art, excepting

the building of La Galgada, are not structural and there

are no parameters for a controlled comparison with

the art of Choquequirao, even with its pure geometric

samples that are not considered here.

The c u lt ur a l a s so c ia ti on

At the present time the main premise for the

establishment of a cultural association between archae-

ological sites and the Tahuantinsuyu empire is the

presence of formalised architecture similar to that of

the city of Cusco, of-the imperial period (approximately

from 1438 to 1533 CE.). Inthis sense Choquequirao is a

very well recognised Cusco-type establishment (llacta)

of the 15th century with an explicit cultural association.

Nevertheless, beyond the area where the most typical

architecture of the settlement is exposed (see Fig. 2),

several archaeological sectors with architecture do not

show a clear cultural association, especially as they

consist basically of extended terraces in zones with

few culturally diagnostic elements.

Although the complex of terraces lacks the cha-

racteristics of the Cusco classic architecture, these can

be inferred using other variables. For example sector

VIII (the llamas) is related, at the level of architectural

design , with two of the most representative sectors

of the settlement: sector XI (Pacchayoq), and the site

of Pinchaunuyoq (Fig. 20); these are big edifices ofterraces with remarkable similarities in the location

and in the general disposition of the structures. Though

the design indicates a parameter of formalised cultural

relation, the construction varies, separating sector vrnand the site of Pinchaunuyoq, which used the same

type of structure, from sector Xl whose construction is

similar to that used inthe central zone of the settlement

with the classical Cusco-type architecture.

The construct ion variable differentiating sector VIII

and the site of Pinchaunuyoq from sector Xl.is crucial

for the establishmen t of a cultural association infavour

of the Cusco state, since this type of construction is

unique and has not been reported in the archaeological

record for any other Andean structure of its time (see

Fig. 6). No significant known wall sample provides a

formal link between the sector VlIl construction and

any other, similar feature corresponding to a local.pre-

Tahuantinsuyu culture, or to any other in the Andes

. or the Amazonia. Establishment of a particular mode

of construction suggests that the structural aspect was

solved locally to serve the architectural needs of the

imperial Cusco occupation.

The occupation of these extensive terrace areas,

with this design and construction, does not have any

precedents in the zone where the local settlements

consist of clusters of circular edifices, like those of

Pajonal (Valencia 2005), located near Pinchaunuyoq.

This implies that the Cusco people occupied those

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 11/12

222 Rock Art Ri!searc i l 2009 - Volume26, Number Z, pp . 213-22.3. G. T ECHEVAlmtA Land Z. VALENC1A G.

areas for their OW!l aims using a massive workforce.

It appears that, independent of the manual labour

and/or the origin of the workers, the design and the

construction indicates a unilineal cultural association

directly related to the imperial Cusco state ofthe 15th

century.

An additional relation can be argued at a purelyfigurative level, taking into account the value of the

scenic aspect of the motifs, that appear oriented to

the east-towards the main plaza of the archaeological

settlement. The orientation to the main area of the

liacia is probably not an accidental feature of the

figurative description of the llamas, whose naturalism

has already been mentioned. They explicitly link to

the plaza, which in this context suggests a significant

cultural association, symbolic, functional or both, also

in favour of the Cusco state.

TIle chronology

Although the documentary information about the

Tahuantinsuyu empire illustrates many aspects of its

development (Rowe 1946; Espinoza 1997), until now

clear documentation had been lacking of different

stages in imperial settlements that generally are

considered of a Single occupation with an ambiguous

'Inca' chronology (Samanez and Zapata 1989; Lecoq

and Duffait 2004; Lumbreras 2005).

The identification of a sequence of architecture in

Choquequirao (Valencia 2006; Echevarria 2008: 47-48;

Echevarria and Valencia 2008: 76-79) has allowed the

identification ofat Ieasttwo stages inthe development

of this llacta, which places the terraces with the'llamas' within the second phase of the settlement.

The horizontal development of Choquequirao,

an an extraordinary scale, is corroborated by the

examination of the twelve. sectors with architecture

of the l lacta and has already been used as the base

for historical correlation, Such historical correlations

suggest that the 'Barnas scene' corresponds to the most

important remodelling of the settlement through the

establishment of new architectural infrastructure,

erected approximately between 1471 and 1493 C.E.,

during the government of the Inca Tupaq Yupanqui.

This remodelling postdates the more formalisedarchi tecture of the central sector that was built during

the development of the early Tahuantinsuyu empire, in

the government of the fuca Pachacuti, approximately

between 1438 and 1471 C. E. In this sense the big

terrace edifices (sectors VIII and X I, and the site of

Pinchaunuyoq) correspond to. a substantial increase

of the area af the settlement, perhaps related to. new .

needs of infrastructure as the ! lacta had to canfront

different political conditions to those at its foundation

(Echevarria 2007). In the 17th-century Choquequirao

was probably completely abandoned.

This relative chronology is sustained, in addition to

the archaeological investigation, by pertinent historical

information (Rowe 1944), which is coherent with the

fact that the Spanish invasion occurred about sixty

years after the proposed date for the construction of

the extended terraces that correspond to the times

of Inca Tu pac Yu panqui. The fast development of

the Tahuanfinsuyu empire, whose impact in the

Andes is extensively documented (Tello 1936; Rowe

1944; Chavez 1992; Morales 1993; Espinoza 1997),

leaves a small margi.nta reach a detailed chranology.Choquequiraomay be one ofthe keys settlements for

the establishment of contexts of cultural correlatian for

the Cuscaculture, and to understand the-chronological

and cultural development of the Tahuantinsuyu

empire from its earlier phases.

Conclusions

The analysis of the Choquequirao rock art has been

an oppartunity without precedent to document and

to study a unique sample of Cusco arlin a complex

architectural context, a context of material components

able to set parameters of cultural and chronological

association. The results of these studies have revealed

not only aspects related to the 'llama' motifs, but related

to the whole archaeological settlement, exposing a

context of cultural correlation of one of the earliest

and most remarkable sites of the history of the Cusco

cultural development.

Given the available evidence it is dear that the

production of the motifs is culturaIIy related to Cusco

society. The figurative nature of the motifs, even in

their singularity, shows a uniform association with

the Cusco culture of the 15th century, corresponding

to the second remodelling of the llacta during the

government of the Inca Tupac Yupanqui. So far there is

no evidence that would sustain an alternative cultural

orchronological relation.

Finally itis consistentto consider that the meaning

of this figurative 'scene' is related to a dominant

imperial state that apparently gave an extraordinary

value to llamas. Given its unique manufacture it is

probable that this' scene' implies a strong situational

relation in a natural region appropriated for gold

productian(Ramero 1909; Bueno 1951;Huertas 1972),

or for cultivation of products like coca, com or beans,

as the historical documentation for the zone suggests

(Huertas op. cit.; Pulgar 1946), and which our pollenanalyses inthe terraces proved to be have been grown

there (Pumaccahua 2005) ..A t least the last activities can

be associated to the terraces' construction and, if we

think in terms of transportation, to the 'llamas scene',

although we still lack the evidence to establish the

specific nature of this relation. However, what these

llamas meant for the imperial Cusco state, or for the

Cusco genera l. society; or even for the foreign observer,

has a varied contextual value that must. be reserved

for future studies.

A ck nowle dgm en isThe authors thank three RA R referees for their review of

this paper. Any remaining errors are the authors'.

8/3/2019 The 'Llamas' from Choquequirao: A 15th-Century Cusco Imperial Rock Art

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-llamas-from-choquequirao-a-15th-century-cusco-imperial-rock 12/12

Rock Art Research 2009 - Volllme 26, Number 2, pr. 213-223. G. 1: ECHEVARRiA L. "nd Z. VALENCJA C.

God Tumi Echevarria Lopez

San Marcos University

Peruvian Rock Art Association (APAR)

Plaza Julio C. Tello 274 No 303. Torres de San Borja.

Lima 41

Peru

E-mail: [email protected]

Zenobio Valencia Garcia

San Antonio Abad del Cusco University

Peruvian Rock Art Association (APAR)o

E-mail;zvaJenciagarcia@gmail .com

Final M5 received 23June 2009.

REFERENCES

ALTAMIRANO,A. 1993. Principales contribuciones pa leo-

zoologicas en los andes centrales durante los afios

1970-1990. B ole tin d e Lima 90: 51-65.

BEDNAR!K,R. G. 2007. R ock a rt s c ience : the sc ientific s tudy ofpulaeourt (2nd edn), Aryan Books International, New

Delhi (1st edn 2001, Brepols, Tumhout).

BONAVIA,D. 1968. La s minas d e l Ab is e o . Universidad Peruana

de Ciencias y Tecnologia, Lima.

BUENO,A. 1970-1971. Sechin, slntesis y evaluaci6n critica del

problema. B ole tin B ib /io gn ijic o d e A ntr op olo gia Ame ric an a

33--34(1970-1971): 201-221.

BUENO, A. 1983. El antiguo vane de Pachacamac, espacio,

tiempo y culture. B ole tin d e Lima, (5)26: 3-12..

BUENO, C. 1951. Geografia tnrreinal de l Peru (siglo XVTll).

Publicado por Daniel Valcarcel, Lima.

CHAVEZ B., M. 1992. Machupicchu un sitio ideal para

investigar y ensenar Ia hisroria y la cultura de los Incas.

InE. Chevarda H. (ed.), Machupicchu, deoenir histcirico

y cultural, pr. 181-182. Universidad San Antonio Abad

deL Cusco, Cusco.

EnIEVARRIA, G. T. 2007. Choquequirao en el contexto

del desarrollo imperial temprano del Cusco, Paper

presented at the VI Seminario de Arqueologfa 'Poder

en los Andes Centrales: Sistemas Culturales y Dominio

Estatal Prehispanico'. 10 and 11 de October, Universidad

Nacional Federico Villarreal, Lima.

ECHEVARRiA,G. T. 2008. C ho ou ec uir ao , u n e stu dio arqueologico

de su arie jiguraJivo. Hipocam po Editores, Li rna.

ECHEVARRIA,G. T. 2009. Las cuatro tradiciones del arte

rupestre colonial del Cusco .. Paper presented to the

Third Conference on Rock Art inHonor to William Breen

Murray, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico, 14

to 17 April 2009.

ECHEVARRiA, G. T. and Z. VALENCIA2008. Arquitectura

y contexto arqueol6gico, sector VIII, andenes 'Las

Llamas' de Choquequirao. Invest igaciones So cia le s 2 0:

63--83. Revista del Institute de Investigaciones Hist6rico

Sociales, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos,

Lima.

ESPINOZA,W. 1997. L os In ca s : e co no m ia , s oc ie da d y e sta do e n la

e r a d e l T ohu an ii ns u qu. Amaru Editores, Lima.

FUNG, R2004. El arte textil en el antiguo peru: sus implicancias

econornicas, sociales, politicas y religiosas, Qu . eh a c e re s d e

l a o r q ue o io g ia Pe ru ana . Compilacum de e sc r ii o s, pp. 225-244.

Museo de ArqueoIogia y Antropologia, UniversidadNacionaI Mayor de San Marcos, Lima.

GRIJWIiR, T . and A. BUENO1988. The history of La Galgada

223

architecture, In T . Grieder, A. Bueno, C. E. Smith and

R. Malina (eds), La G alga da , P er u. A prece ramic cu l ture in

transition, pp. 19-67. University of Texas Press, Austin.

HUERTAS, L. 1972. Memorial acerca de las cuatro ciudades

inkas situadas entre los rios Urubarnba y Apurimac.

Historia y Cuuura 6: 203-205.

KARP, E. 2005. Choquaquirao: historia, identidad cultural

y patrimonio arqueol6gico. In Choouequirao el Misterio

de las lla ma s del sol ye l culio a los a pu s, pp. 31-52. Fondo

Contravalor Peru-Francia, Impresso Grafica S.A.,

Lima,

KAUFFMANN,F. 1973. E l Peru antiguo. Historia g ene ra l de Los

Peruanas, Vol. 1, Talleres Crafieos IBERIA S.A., Lima,

LECOQ, P . and E. DUHAIT 2004. Choqek'irao, un nouveau

Machu Picchu? A r cMo l og e 411: 50-63.

LUMBRERAS,L. 2005. La arqueologia de Choquequirao. In

Choqueouimo e l misierio de /.a s lL am a s d el so l y el culia a

lo s apus, pp. 127-147. Fondo Contravalor Peru-Francia,

Impresso Grafica S.A., Lima.

MORALES,D.1993. Historia arqueol6gica del peru. Compendia

hisior ieo de l PeriJ, VoL I. Editorial Milla Batres, Lima.

PULGAR,J. 1946. Historia y geogra fo : ! de l Pent Tomo 1. L as o ch o

r eg io ne s n atu ra le s d el Peru. Universidad Nacional Mayor

de San Marcos. Lima.

PUMACCAHUA,E. 2006. Estudio palinologico en el complejo

Aarqueologico de Choquequirao, Sector VIII (Las

Llamas), Cusco, Peru. Unpub!. report presented to the

Director del Proyecto de lnvestigacion, by Zenobio

Valencia Garda, Cusco,

ROMERO,c ., A. 1909. Informe del senor Carlos A. Romero,

individuo de numero dellnstituto sobre las ruinas de

Choqquequirau. Revista Historica, Torno rv , pp. 87-103.Organo del Institute Hit6rico del Peru, Lima.

ROWE, J . 1944. An in troduc tion to the a rcha eology of Cuzco.

Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeologyand Ethnology, Harvard University. Vol. XXVII , No.2.

Cambridge, Mass ..

ROWE,J . 1946.lnca culture at the time of the Spanish conquest.

In J.H.Steward (ed.), H an db oo k o f S ou th Ame ric a n in dia ns ,

Vol. 2, pp. 183--330. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of

American Ethnology Bulletin 143, Washington, DC.

SAMANBZA., R. and J . ZAPATA1989 ..E 1 conjunto arqueo16gico

inca de Choquequirao. Cuadernos de Arqueologia 1:

17-24.

SAMANIEGO, L., E. VIl.~GARAand H. BISCHOF 1985. New

evidence on Cerro Sechin, Casma Valley, Peru. In C.

Donnan (ed.), Ea rly a rc hite ctu re in th e A nd es , pp. 165-190.Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection,

Washington.. DC.SCHAEDRL, . 1951. Mochica murals at Pafiam arca. Archaeology

4 (3): 145-154.

TELLO, J . 1929. Antiguo P er u, p rim e ra epoca. Editado por

Ia Comision Organizadora del Segundo Congreso

Sudamericano de Turismo, 'Lima.

TELLO,J. 1936. La civilizaci6n de los Inkas, Leiras 6: 5-37.

VALENCIA,Z. 2005. Tnforme catastro y delimitacion <Jrqueo-

16gica. Implementaci6n plan maestro Choquequirao.

UnpubL Report presented to the Instituto Nacional de

Culture, Cusco.

VALENCIA,Z. 2006. Investigacion arqueol6gica del com plejo

arqueol6gico de Choq uequirao, Sector VllI 'Las Llamas'.

lnforme Final 2005. UnpubL report presented to the

Institute Nacional de Cultura, Cusco,

RAR 26'>l39

![Las llamas de Choquequirao, arte imperial cusqueño en roca del … · 2011. 9. 25. · investigaciones sociales │Vol.14N°24, pp.67-88 [2010] UNMSM/IIHS, Lima, Perú 67 Las llamas](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/606e7a7011c3394658208522/las-llamas-de-choquequirao-arte-imperial-cusqueo-en-roca-del-2011-9-25-investigaciones.jpg)