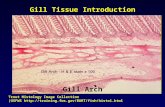

Gill Arch Gill Tissue Introduction Trout Histology Image Collection (USFWS .

The implications of diversity and disability for evaluation practice: commentary on Gill

-

Upload

barbara-lee -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of The implications of diversity and disability for evaluation practice: commentary on Gill

The Implications of Diversity andDisability for Evaluation Practice:Commentary on Gill

BARBARA LEE

As evaluators, when we gather information about a program,we know that it is not sufficient for us to talk only with thelargest group of users. If the data we gather are to be mean-ingful to those who will use the results of our evaluation, weknow we must understand the diversity among users as itaffects their interactions with program elements. Thus we payattention to such human differences as age, gender, race andidentity stratifying our samples, and applying other techniquesto avoid misleading those who will use our evaluation resultsabout what will work for whom, how well, under what condi-tions, and why.

Now Carol Gill challenges us to attend to other dimen-sions of human difference, those people with visible and invis-ible disabilities that able people too often fear and try to avoidnoticing. These are the people whose differences from cultural expectations affect theirphysical, emotional, mental, or social access to places, programs, opportunity, security, andsuccess. Dr. Gill challenges us by calling to our attention the significant possibility thatfailure to notice is not harmless. In fact, by not paying specific attention to the experience ofpeople with disabilities, we may miss information that is crucial to assessing value; indeed,our best methods may actually bring misleading results, and will not guarantee a usefulevaluation. Dr. Gill suggests that we may fail to comprehend the information we gather, andmay even distort meaning, because of biases we share with the majority culture, and becausewe do not even understand what it is we do not know. There is no evaluation professional orpractitioner who could fail to be concerned about these challenges.

One problem is that it is always difficult to truly appreciate the lived experience of“otherness.” This is especially true when we are the recipients of unearned privileges, grantedby the accidents of birth and genetic heritage and by the luck to be members of the majority,

Barbara Lee ● Louis de la Parte Institute, University of South Florida, 13301 Bruce B. Downs Blvd., Tampa, FL33612-3699; Tel: (813) 974-7011.

Barbara Lee

American Journal of Evaluation, Vol. 20, No. 2, 1999, pp. 289–293. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.ISSN: 1098-2140 Copyright © 1999 by American Evaluation Association.

289

whatever the majority is. Most of us never thought about stairways and curbs as barriers, untilpeople with crutches and in wheelchairs became a common sight. We had not earned theprivilege to move freely and rapidly, even without cars, but we had it. We were simply blindto the formidable barriers created for people whose legs did not work like ours. People whohave no intention to discriminate against those whose race or cultures are different from theirown fail to notice people from ethnic minorities or from the disability culture, who find thatstigma and discrimination are their experience, in spite of laws intended to assure equal rightsto all.

Dr. Gill reminds us that the experience of “otherness” is likely to be experienced byanyone who lives long enough to experience some of the debilitating effects of age. If it isclear that we have a stake in this issue, both personally and professionally, what is theappropriate response for evaluators, and how important is it to respond to the challenges Dr.Gill sets out for us?

I would suggest that it is vitally important for evaluators and the profession of evaluationto become culturally competent with “otherness,” and to be frank in our admission thatevaluation as a profession has been far too blind to its implications. But to respond to thischallenge will require us to learn how to think in paradigms that move beyond traditionalreliance on random assignment and experimental design to establish cause and effect. It willnot be enough to sample a population randomly and to emphasize generalizability. Thosestrategies inevitably give us only the majority perception of “truth.” Now we have to askwhether a majority truth even applies to non-majority members, and finding the answers willrequire mixed method, qualitative inquiry, much more use of participatory approaches toevaluation design and interpretation, and alternative ways to gather information. Simply put,we will have to become much more conversant with particular and highly subjectiveexperience, and will be able to rely much less on so-called “objective” inquiry.

Just one example: when recipients of health services are asked for their satisfaction withservices, the person with private insurance and the transportation needed to access a numberof different health care providers will probably give us “true” answers. But what if the samequestion is asked of someone whose access to housing, rent subsidy, medications necessaryfor life and perhaps sanity, come from the one agency that is within reach by publictransportation and Medicaid? In that situation, it is not nearly so certain that we will hear thetruth about the experiences of those who are poor because they are disabled. The chances arevery good that those people have already learned to settle for less, when it comes to medicalcare, or that they will be unwilling to risk criticizing the programs of those who hold so muchpower in their hands, no matter how much we assure them of “anonymity.” English (1997)pointed out the threat that potential sanctions have on cooperation from people who aredependent on the mental health services which are being evaluated, and Rosenheck and Lam(1997), for example, have documented cost barriers to service use. Also, Mayberg (1996)found that people with serious mental illness who are hospitalized do not feel they have“choice,” and thus give you the data they believe you want. Lack of choice in other servicesettings is likely to have the same biasing effect. An evaluation, traditionally but naivelydesigned regarding culture, disability, and other particularities, will give us a false assess-ment, not just one that is incomplete.

A second important implication for evaluation practice is found in Dr. Gill’s descriptionof the social model of disability. The implication is clear that evaluators will have to be muchmore conscious of the subtlety and strength of cultural training, and how that affects powerdifferences and, therefore, relationships, between ourselves and those who contract for

290 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF EVALUATION, 20(2), 1999

evaluation—between funders and providers, between providers and consumers, betweenconsumers and the culture in which they live, and between cultural groups within the largersociety. There are social power differences among these constituencies. Failure to understandassumptions trained into us by society will lead us to rely too blindly on the supposedobjectivity of methodology, which, in turn, can only reinforce and perpetuate power ineq-uities. Methods are only truthfully “objective”when diversity in populations and the power ofdifferent groups are appropriately addressed. Questions of all groups must be included andmethods must fit the cultures and power positions of those from whom we gather data.

In a 1992 presentation, Kang described the assumptions in managed care evaluationstudies that consumers have true choice, can make informed choices, are empowered topursue their rights, and have control of where their service dollars are spent. Unfortunately,these do not generally apply to people dependent on public mental health systems. Further-more, these barriers may exist even when the individual’s mental illness is in full remission,further confounding the outcome questions. Even when outcome measures identify theirassumptions carefully, many vulnerable populations are too small to be picked up by themin typical study designs.

Madison (1992) recommends primary inclusion of minority participants in evaluation.This means direct involvement inall phases of program development, from conceptualizationof problems, to the evaluation and interpretation of findings. But in my experience as anevaluator, it is necessary to become “bilingual” in the culture and experience the marginal-ized groups, even when I think I am a “member” myself. Also, additional time and methodssuch as empowerment evaluation (Fetterman, 1994) and the emancipatory alliances Mertens(1997) describes, must be utilized, if democratic participation by groups such as those withserious mental illness is to happen.

Clay (1991, 1991–1994) points out that there are three components of empowerment:personal, social, and civil. When people first come out of the acute phases of serious mentalillness, they are often traumatized, stunned by their loss of control over their lives, and arereduced to living at half the level of poverty, dependent upon “systems” for necessarymedical treatment and other services. This disempowerment by financial dependency, socialstigma, and laws that fail to protect civil rights, makes recovery of personal empowerment,and thus participation as an equal with research professionals, difficult. However, theevaluation professional has tackled similar problems before, and many leaders in the field,such as House, Guttentag, Stake, Mertens, and Patton, among others, have worked toovercome them. What is important to remember, is thatwe have the power, and it isourobligation to learn how to share that to level the playing field.

The social or minority group model of disability, which Dr. Gill described, suggests that“disability,” or otherness, like gender and race, is not defined as defects in the individual thatneed fixing. This is a radical departure from the models that are clearly built into most of thecurrent research on health care programs. In the social model, the consequences of disabilityare primarily the result of stigma and discrimination which are imposed by society on thosewho deviate from cultural standards of physical, mental, or social performance. The povertyand poor quality of life for people disabled by mental or physical disease, therefore, cannotbe relieved with programs designed to remove symptoms that may not be “curable”. Indeedwe need to be evaluating ways to restore power and autonomy to the lives of thosedisempowered in society. The paradox of power is that those who have it must recognize thatfact before they can share it. Is it not the obligation of a professional evaluator to help get thequestions right?

291Commentary on Gill

All stakeholders in a particular evaluation context do not have equal power. Often thispower is unsought—a product of the structure and collective unconsciousness of societyitself. But lack of awareness, like knowledge of the law, is no excuse for avoiding respon-sibility. The results of our evaluations, whether we like it or not, will either reinforce thatunconsciousness, and thus the persistence of social inequity that can be literally life-threatening to those on the down-side of the power differential, or it will bring it toawareness. Whether those who contract for the evaluation specifically request it or not, thefailure to bring appropriate attention to the effects of power differences in the system beingevaluated, will result in reinforcing and perpetuating stigma, discrimination, and disempow-erment of people who are disabled or identified as a minority. It may be perfectly legitimateto compare groups of people, but not if we are actually measuring poverty and powerlessness,rather than response to the programs we are evaluating.

One issue that may seem both unfamiliar and uncomfortable to evaluators is the need forus to become very “self” conscious in the exercise of our work. Most of us have grown upwith a host of unearned privileges. We forget that we have more time and informationavailable to us because we can walk, see, and hear well. We don’t notice that people listento us with more respect than others may get just because we are educated, or male, or tall,or well dressed, or heterosexual, or visibly a member of the majority ethnic group. We forgetthat we, too, give the perspectives of people like ourselves more credibility than we give topeople who differ from us.

We know that instruments can themselves alter the phenomena we are trying tomeasure, often in ways that confuse and muddy the truth. What we often fail to recognize isthat we, too, are instruments, affecting strongly the very questions that will be asked and,therefore, have even a chance of being answered, as well as the measurement itself. Nothingbut the determination to ferret out our own cultural assumptions and biases can counter thisand avoid unacknowledged distortions on the evaluation work that we do. If we do notunderstand our own biases, we will make those who use our work victims of those biases.

Evaluators cannot afford to be professionally, culturally, and socially complacent. Ourwork potentially impacts many lives besides our own, both abled and disabled. A centralvalue of our profession is that we seek data-based ways to improve the quality of what weevaluate, not just to confirm what may be a biased status quo. If we do not exerciseself-reflection about our assumptions and biases, our methods, our questions, and the hiddenagendas of ourselves and others, we will inevitably build those assumptions, biases, andagendas into our prescriptions for evaluation design, and into the meaning we extract fromour data.

Those of us who are “abled” often fear the conditions of our bodies and minds that welabel “disabled.” I think it was President Abraham Lincoln who suggested that what weneeded instead of less fear, was more courage. It will take courage, as well as humility andcreativity, to meet the challenge of working effectively with people from disempoweredgroups. But the young and vital profession of evaluation has never operated solely in the safeterritory of popular and comfortable answers. If we value something, we can do it.

REFERENCES

Clay, S. (1991). Empowerment & Recovery.Empowerment News, New York State: Recipient Em-powerment Project.

292 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF EVALUATION, 20(2), 1999

Clay, S. (1991-1994). Rights of Mental Patients.Empowerment News, New York State: RecipientEmpowerment Project.

English, B. (1997). Conducting ethical evaluations with disadvantaged and minority target groups.Evaluation Practice, 18(1), 49-54.

Fetterman, D. M., Kaftarian, S. J., & Wandesman, A. (Eds.) (1996).Empowerment evaluation.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kang, MD., J. (1996). The Future for Quality in Managed Care. Outcomes Conference, Tampa, FL,April 29, 1997.

Madison, A. (1992). Primary inclusion of culturally diverse minority program participants in theevaluation process.New Directions for Program Evaluation, 53, 35-43.

Mayberg, S., (1996). The Future for Quality in Managed Care. Outcomes Conference, Tampa, FL, April29, 1997.

Mertens, D. M. (1997).Research methods in evaluation and psychology: Integrating diversity withquantitative & qualitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rosenheck, R., & Lam, J. A. (1997). Client and site characteristics as barriers to service use byhomeless persons with serious mental illness.Psychiatric Services, 48(3): 387 ff.

293Commentary on Gill