The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraine in patient with intractable epilepsy: case report

Transcript of The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraine in patient with intractable epilepsy: case report

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraine in patientwith intractable epilepsy: case report

Silvio Basic • Davor Sporis • Darko Chudy •

Gordan Grahovac • Branimir Nevajda

Received: 3 September 2011 / Accepted: 5 June 2012 / Published online: 22 June 2012

� Springer-Verlag 2012

Keywords Epilepsy therapy � Chronic pain � Headaches �Migraine � Vagus nerve stimulation

Abbreviations

VNS Vagus nerve stimulation

EEG Electroencephalography

IED Interictal epileptiform discharges

SPECT Single photon emission computed tomography

EEG Electroencephalography

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

V-EEG Video EEG

VAS Visual analogue scale

NTS Solitary tract nucleus

LC Locus coeruleus

Dear Editor,

A 42-year-old female had a long history of partial complex

seizures dating from the age of 13. She was treated with the

following anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs): primidone and

phenytoin. In 2003, she had stopped AED treatments vol-

untarily due to ineffective medical therapy, and shortly

after she was admitted again because of convulsive epi-

leptic status. By 2003, she was experiencing six or seven

seizures monthly. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

demonstrated a localized atrophy of the left middle frontal

gyrus with a subcortical area of encephalomalacia.

Electroencephalography (EEG) disclosed left fronto-centro-

temporal interictal epileptiform discharges (IED) with diffuse

paroxysmal dysrhythmic changes and elements of slow spike-

wave complexes. Single photon emission computed tomog-

raphy (SPECT) showed an area of hypoperfusion in the left

frontal area.

In 2008, she experienced ten partial seizures per

month, and by that time, the following AEDs failed for the

patient: primidone, phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine,

oxcarbazepine, vigabatrin, and gabapentin. She was eval-

uated for 14 days by video EEG (V-EEG) monitoring,

which confirmed that the origin of the seizures was from

the left frontal region.

The patient also experienced typical common migraine

attacks since puberty, with two or three episodes of

migraine attacks per week, which were resistant to acute

treatment. Migraines were characterized by unilateral pul-

sating headaches with photophobia followed by nausea and

vomiting. Scintillating scotoma preceded attacks. These

migraine attacks were not related to the epileptic seizures.

The average intensity of headache on visual analogue scale

(VAS) was eight to nine and the migraine disability

assessment score (MIDAS) was about 50.

In 2008, the patient refused grid electrode placement

and possible neocortical resection.

In 2009, she was offered VNS (NCP; Cyberonics,

Webster, TX, USA) implantation. VNS was implanted in

May, 2009. VNS was turned on seven days after surgery,

and parameters were 0.25 mA, 30 Hz, 500 ls, with an ‘on’

time of 30 s every 5 min. These settings were well toler-

ated by the patient. After this implantation, the patient was

discharged with these AEDs: oxcarbazepine (2,400 mg),

vigabatrin (1,500 mg), and gabapentin (2,400 mg). Six

months after the surgery, the VNS settings were corrected to

1.75 mA, 30 Hz, 500 ls, and ‘on’ time of 30 s every 5 min.

S. Basic � D. Sporis � D. Chudy � G. Grahovac (&) �B. Nevajda

Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical Hospital Dubrava,

Av. Gojka Suska 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

e-mail: [email protected]

123

Neurol Sci (2013) 34:797–798

DOI 10.1007/s10072-012-1135-5

According to the patient’s seizure diary, 18 months after

the surgery, the patient noted a significant decline in the

number and intensity of migraine attacks. She reported a

mean of one migraine attack per month that responded

quickly and effectively to symptomatic treatment. The

average intensity of headache after the surgery was on

VAS 1–2 and MIDAS was 2. The control EEG became free

of IED after the surgery.

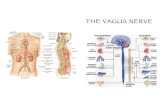

VNS is a well-established method for treating refractory

epilepsy, but the exact mechanism of action of VNS is still

unknown [1]. We can assume that the neuromodulation

potential of the VNS is responsible for restoring normal

brain function not only in brain areas responsible for epi-

lepsy attacks and depression but also in brain regions

responsible for pain that was demonstrated in animal

models.

A retrospective study by Hord et al. [2] showed

improvement of migraine in patients treated with VNS for

intractable epilepsy and concomitant chronic pain.

Migraine attacks showed reduction in both frequency and

intensity which is consistent with our results. The VNS

impact on chronic pain was noticed briefly after VNS

implantation, 1–3 months in the study of Hord et al. We

also noticed an almost immediate effect of VNS to

migraine after the initiation of therapy in our case. A case

report by Sadler et al. [3] also had similar findings as we

have, the number of migraine attacks was significantly

lower after VNS implantation, and yet again VNS effect on

migraine was achieved 2 months after the initiation of

therapy. Although VNS parameters were changed due to

insufficient seizure control, the effect of VNS to migraine

remained constant, as it was in our case also. Mauskop [4]

presented six patients with severe drug-refractory migraine

and chronic cluster headaches. In all of them, VNS was

implanted, and in five of them, there was a dramatic

improvement of their headache. A detailed literature search

revealed several smaller clinical series and case repots such

as ours that VNS can reduce migraine attacks in population

of patients who had VNS device implantation for epilepsy.

[2–5].

Improvement of IED in EEG in our case were compa-

rable with results of study of Wang et al. [6]. They found

that interictal EEG activity was influenced by long-term

VNS, and IEDs in the EEGs progressively decreased with

months of action, which was also observed in our case.

That can explaine mechanism of action of VNS as ‘‘neural

network regulation’’ by desynchronization of abnormal

synchronous epileptic activity.

The result from our case and other small series offers

novel approach in therapy of intractable migraine but fur-

ther randomized trials are necessary to evaluate true

validity of VNS in treatment of intractable migraine.

Conflict of interest The authors have no relevant affiliations or

financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial

interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials

discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultan-

cies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants

or patents received or pending, or royalties. No writing assistance was

utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

1. Penry JK, Dean JC (1990) Prevention of intractable partial seizures

by intermittent vagal stimulation in humans: preliminary results.

Epilepsia 31(Suppl 2):S40–S43

2. Hord ED, Evans MS, Mueed S, Adamolekun B, Naritoku DK

(2003) The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraines. J Pain

4(9):530–534 [pii: S1526590003008095]

3. Sadler RM, Purdy RA, Rahey S (2002) Vagal nerve stimulation

aborts migraine in patient with intractable epilepsy. Cephalalgia

22(6):482–484. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00387.x

4. Mauskop A (2005) Vagus nerve stimulation relieves chronic

refractory migraine and cluster headaches. Cephalalgia 25(2):82–86.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00611.x

5. Lenaerts ME, Oommen KJ, Couch JR, Skaggs V (2008) Can vagus

nerve stimulation help migraine? Cephalalgia 28(4):392–395. doi:

10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01538.x

6. Wang H, Chen X, Lin Z, Shao Z, Sun B, Shen H, Liu L (2009)

Long-term effect of vagus nerve stimulation on interictal epilep-

tiform discharges in refractory epilepsy. J Neurol Sci 284(1–2):

96–102. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.012

798 Neurol Sci (2013) 34:797–798

123