The Baroque; The UNESCO Courier: a window open on...

Transcript of The Baroque; The UNESCO Courier: a window open on...

-ja*?*

'l¿*ñ& Z

r -çam*-

r , ->i

' »*Vl

SPff i

A ífrae ío /ft;e

58 Brazil

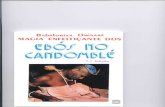

The candomblé cult

Modem Brazil has been shaped by a process ofracial and cultural intermingling which beganduring theperiodwhenforms ofbaroque art andarchitecture importedfrom Portugal were beingadapted to the Brazilian environment. Blackslaves transported from Africa were compelledto accept the Catholic faith, but preserved inmodified form many of their ancestral beliefs

and rituals. Some of the syncretic cults andrituals which arose from this fusion of culturesstillhold sway in parts ofBrazil. One of them ispractised by members of the candomblé ritualgroups which first appeared in the 19th centuryin the city ofSalvador, formerly Säo Salvador deBahia de Todos os Santos, the capital ofAfro-Brazilian culture. Above, four women membersof a candomblé group at prayer before an altarin the lavishly gilded baroque church of SäoDomingo, in Salvador.

Editorial n:::

The baroque age in western Europe began sometime around 1600 and lasted untilthe mid-eighteenth century. It saw the flowering of a culture which, although itdeveloped mainly in the Latin countries, spread to eastern Europe and above alltook root on a grand scale in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of SouthAmerica, where an important hybrid form of baroque art emerged.

Baroque culture was the product of an age marked by profound economic andsocial crisis during which the pomp and ceremony associated with absolutemonarchies and the Counter-Reformation could not conceal signs of depression ina Europe whose religious beliefs had been shaken by the Lutheran Reformation andby the first conquests of rationalism and modern science.

This acute sense of crisis, which would last until its extinction a century and a halflater by the optimistic humanism of the Enlightenment, shaped many of the .characteristic features of baroque art and literature: disenchantment, a sense of theillusory nature of the world of appearances, a theatrical conception of life, an acuteawareness ofpassing time and of the certainty and finality of death, a taste forartifice and display, and, in art, for exaggerated, "expressionist" forms. Butparadoxically enough, such depressive tendencies triggered off an explosion ofsensuality and whetted an appetite for life and enjoyment which is revealed in thedazzling exuberance of the baroque visual arts and the prodigious universe of soundwhich is baroque music.

The baroque art and culture of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe alsoflourished in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of America, where in time itunderwent a transformation. Models imported from the Iberian peninsula weregradually adapted, subtly modified and given an original imprint as the process ofethnic and cultural intermingling overflowed into art. Latin American baroquewould eventually find full expression in such magnificent creations of folk art as thechurch ofTonantzintla in Mexico, the "Sistine Chapel" of colonial art.

Some critics consider that the Baroque is not only a European and Ibero-American phenomenon but a " cultural constant" which recurs throughout thehistory of art. It is undeniable that outside Europe and the Americas, in suchdifferent cultural regions as Persia, China, Japan and Kampuchea, forms ofexpression closely related to baroque sensibility have appeared. It is also significantthat a century like our own, a century of crises, upheavals and vacillating beliefs,should feel an affinity with certain seventeenth-century forms of art and culture.Perhaps it is justifiable, then, to consider the Baroque as a category of aestheticsensibility and thus recognize its global dimension.

This number ofthe Unesco Courier does not claim to paint a complete picture ofthe immense world of the Baroque . What we have tried to do is to show some of itsmost characteristic manifestations and some of its finest achievements.

Editor-in-chief: Edouard Glissant

September 198740th year

An age of exuberance,drama and disenchantment

by Peter Skrine

Three great domesby Giuho Carlo Argan

The musical offeringby Alberto Basso

Spain: An art of gilt and pathosbyJulián Gallego

Baroque as a world philosophyby Edouard Glissant

Sculpture, theatre of the sublimeby François Souchal

The stately heritage of PortuguesebaroquebyJosé-Augusto Franca

Italy: The great illusionistsby Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée

LatinAmerica: 'A new form of self-

expression'by Leopoldo Zea

The Angel with the Arquebusby Miguel Rojas Mix

Brazil: The triumph of O Aleijadinhoby Augusto C. da Silva Telles

10

11

14

18

20

27

30

34

36

39

CentralEurope: The art of persuasion 42by Christian Norberg-Schulz

Baroque in the Slav countriesby Georgii Gatchev

46

A time to live...

BRAZIL : The candomblé cult

Cover: The Glorification ofUrban VIII'sPontificate (1633-1639) painted by Pietro daCortona on the ceiling of the main hall of thePalazzo Barberini in Rome (see article page 30 andcolour pages).Photo© SCALA, Editions Mazenod, Paris

Back cover: detail of mouldings on the ceiling ofthe church of Santa Maria Tonantzintla (c. 1 700),near Puebla, Mexico (see article page 34).Photo Kai Müller© CEDRI, Paris

The Courier EnglishFrench

Italian

Hindi

Turkish

Urdu

Macedonian

Serbo-Croat

Finnish

Swedish

A selection in Braille is

published quarterly in English,A window open on the world

Spanish Tamil Catalan Slovene BasqueFrench, Spanish and Korean

Published monthly in 33 languages Russian Hebrew Malaysian Chinese Thai

by UnescoThe United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization

German

Arabic

Persian

Dutch

Korean

Swahili

BulgarianGreek

Vietnamese

ISSN 0041-5278

7, Place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris. Japanese Portuguese Croato-Serb Sinhala N°9-1987-CPD-87-l-449A

An age of exuberance, drama anddisenchantment

BY PETER SKRINE

WHAT does Baroque mean? Thereare many overlapping definitions.To some scholars and art histo¬

rians who have written well about it,

Baroque signifies a mode of European paint¬ing, a style of architecture, a cultural phe¬nomenon which found its most effective

expression in the fine arts and the appliedarts. To them, and rightly so, it is above allsomething visual.

But to many other scholars and literaryhistorians, Baroque means an attitude to lifewhich arose out of that great revival ofcultural energy and aesthetic values knownas the Renaissance, from which it was sepa¬rated by the deep spiritual and religiouscrises which are associated with the Protes¬

tant Reformation.

As a result, baroque literature, whichflowered in the 1620s and 1630s and reached

its zenith around 1660, is characterized bysharp contrasts and antitheses: its authorsdelight in the sensual beauty of things andare fond of describing them in opulent, evenflowery, detail, but they are also capable ofbrooding darkly on the deeper mysteries oflife and eternity. Its playwrights extol heroicvalour and steadfastness, but enjoy the colli¬sion between such virtues and the passions ofthe heart, which they evoke with extraordin¬ary vigour, eloquence and verve. Thesequalities may be seen in the plays of theGerman baroque poet Casper von Lohens-tein (1635-1683) and even in those of hisFrench contemporary Jean Racine (1639-1699).

The baroque attitude to life found elo¬quent expression in literature and music aswell as in architecture and painting. In allthese arts it manifests itself most obviouslyin a dynamic relationship between underly¬ing control of form, a strong desire to createa sense of movement, and a delight in orna¬mental detail. In countries where it has left

strong and indelible traces, there is a naturaltendency to rate it highly and to describe the'finest products of seventeenth-century artand literature as baroque without furtherdefinition. This is often the case in Italy,Spain and the Latin-American countries,and in Austria, the Federal Republic of Ger¬many, the German Democratic Republic,and Czechoslovakia.

In England and France, however, there isa deeply ingrained and understandable reluc¬tance to accept the term. Indeed, all coun¬tries with strong Protestant Christian tradi¬tions, like England and the United States,tend to regard the Baroque as a typicallyRoman Catholic phenomenon, as somethingalien to their own culture. The case of

France, however, reveals how complex thesituation really is, for there the Baroque

coincided with what the French are justlyproud of calling their "classical age", whichrightly or wrongly they see as its antithesis.

The Baroque developed at different speedsand different levels of intensity in differentplaces. Some areas of art and literature mightbe more affected by it than others and some¬times, too, it could coalesce more or less

naturally with indigenous traditions andways of being. Italy, already the home of theRenaissance, played a large part in its emer¬gence and its radiation to other parts ofEurope. But should we locate its sourcesthere alone? There are also valid argumentsfor seeing the Baroque as the expression of astate of mind and an attitude to the world

which arose simultaneously in many dif¬ferent parts of Europe and which even hadcounterparts in other, more distant placessuch as the Iran of Shah Abbas (1587-1629),the China of the early Ch'ing Dynasty andthe Japan of the great dramatist Chikamatsu(1653-1725).

But let us stay in Christian WesternEurope. There two significant factors wereperhaps more responsible than any othersfor the rise of the Baroque. One was theemergent concept of absolute monarchy, theother was the popularity of play-acting andtheatre. Europe had not witnessed thesethings on such a scale since the emperors andvast amphitheatres of the ancient RomanEmpire, one thousand years before. Whenabsolutism and the theatre came together,and powerful seventeenth-century sov¬ereigns commanded that splendid perfor¬mances of plays be given in their magnificentnew palaces, the Baroque was more strik¬ingly in evidence than anywhere elseexcept in the ceremonies and imposingbuildings of the Roman Catholic church.The Church's claim to universal spiritualauthority and its highly-developed sense ofoccasion made it a generous patron ofbaroque artists, musicians and poets. Itwould be impossible to overstress theimportance of royal prestige, spiritual valuesand dramatic display in Europe's baroqueachievement.

A pervasive image captures the baroqueage's view of the human condition and itslove of the theatrical : the world as a stage. Tothe English speaker this image recalls Shake¬speare because it occurs in his comedy AsYou Like It. But the same notion can be

found in all the major literatures of Europe.The rich seaport of Amsterdam opened itsmunicipal playhouse in 1638; over its doorcould be read a couplet by the great Dutchpoet of the age, Vondel, which proclaimed"The world's a stage: each plays his role andgets his just reward".

Meanwhile in Holland's political andCONTINUED PAGE 7

The baroque period has been called "the goldenage of the clock-maker's art", and an acuteawareness of time slipping by is a recurrenttheme in great works ofcontemporary literaturesuch as Shakespeare's plays and the sonnetsof the Spanish poet Francisco Quevedo. Above,L'habit d'horlogère, an early 18th-century en¬graving showing a pendulum clock, an inven¬tion of the baroque age.

Baroque art is characterized by a sense ofactiv¬ity and movement which contrasts with theorder and restraint ofclassicism. To escapefromthe rigidity of orderly rectangular areas inher¬ited by the Renaissance from Greco-RomanAntiquity, baroque architects often used twistedcolumns, the mostfamous examples ofwhich arethose designed by the Italian architect, sculptorandpainter Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680)for the bronze baldacchino or canopy (right)over the high altar in St. Peter's basilica, Rome.The dramatic 34-metre-high baldacchino wascommissioned by Pope Urban VIII and builtbetween 1624 and 1633 beneath the great domedesigned by Michelangelo.

M?

rttfj V

11* 41

The world's a stage

"All the world's a stage", says a character inShakespeare's comedy As You Like It, and theSpanish dramatist Calderón de la Barca entitledone of his early works El Gran Teatro delMundo (The Great Theatre ofthe World). Suchtheatrical images of the human condition per¬vade the baroque age, which saw an extraordin¬ary flowering of the dramatic arts, the magnifi¬cence of Roman Catholic Church ceremoniesand the pomp of absolute monarchies. In addi¬tion to Shakespeare and Calderón, other great17th-century dramatists ofwestern Europe wereCorneille, Racine añd Moliere in France, and

Lope de Vega in Spain. Baroque stage sets weredesigned, and new forms of theatre machinerywere developed for the staging of spectacularproductions. Above, decor by the Italian stagedesigner Giacomo Torelli for a production ofCorneille's musical tragedy Andromède. Left, ascene from a performance of Calderón'splay Lavida es sueño (Life is a Dream) at a Frenchdrama festival.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 4

commercial rival, Spain, Vondel's contem¬porary Calderón de la Barca was writing hisfamous masterpiece El Gran Teatro delMundo, the play which gives the image of theworld as a stage its supreme baroque inter¬pretation: for here God Almighty is himselfthe author of the play which is produced onthe stage of our human world after the cur¬tain of chaos has risen. This play is actedextempore by the various men and women towhom its parts are given: ambitious king andbeautiful woman, overworked peasant andbullied beggar, wise religious person andcomplacent rich man, they may be stereo¬types, yet they are caught up so realisticallyin the act of living that they seem to come tolife before our very eyes. Of course theirperformances turn out less well than Godhad hoped, and divine Grace, the prompter,has a very difficult task with such all-too-human actors. But fortunately God is also anindulgent author and spectator. The climaxof Calderón's play, like the massive Spanishaltarpieces of the period, confronts its spec¬tators with the timeless message central tothe Christian faith: the sacrifice of Christ

and mankind's redemption as seen throughthe eyes of a post-Reformation SpanishRoman Catholic poet with a truly baroqueimagination.

Baroque men and women were alwaysconscious that the eyes of God and the worldwere upon them. But this did not lead to self-consciousness in the modern post-Romanticsense. Instead it fostered a sense of self-

esteem and an awareness of the importanceof cutting a figure in the world, of projectingan image as meaningful as those conveyed bythe painting, sculpture and drama of theperiod. Maybe the painted portraits of theBaroque, like its stage productions and thedescriptive passages in its profuse pastoraland courtly romances, did not seem as unre¬alistic to their contemporaries as they per¬haps now seem to us.

Like painted portraits, baroque palacesreflect their builders' views of themselves.

They are panegyrics in stone, and their pur¬pose was to extol the virtues and victories ofthose who lived in them. In order to laud

their names and magnify their deeds,baroque princes also required the services ofwriters, who were usually ready to placetheir talents at the disposal of their patronsand to praise them in fulsome odes, light-hearted wedding poems and sonorous epi¬taphs, all written to order. Financial reasonscertainly had a part to play in this, but onesenses the presence of profounder and morecompelling motives. There are times whenthe balance between meaning and hollowbombast, triumph and despair, is so finelycaught that the desire of baroque artists toexalt great men and their achievements canstrike us as a heroic show of defiance and

a bold attempt to drown their sense ofinsecurity.

A note of disenchantment was present inthe Baroque right from the start. Its fond¬ness for play-acting and for the metaphor ofthe stage reveals its deep-seated awarenessthat appearances are all illusion. Its flam

boyant praise of great men and heroes as inthe plays of the French Corneille, theEnglish Dryden and the GermanGryphius may just have been an attempt topostpone the oblivion that must finallyengulf all things, even the greatest. Amidstall the colour, glitter and extrovert joy ofliving so characteristic of the baroqueperiod, there was a darker and more search¬ing side to its literature. "Chaque instant dela vie est un pas vers la mort," the Romanemperor Titus realizes in the last act of Cor-neille's late tragedy The et Bérénice(1670).

But when the play is over, what then? Thepeople who inhabited the baroque worldcould never entirely forget that life is pre¬carious and short indeed in comparison tothe certainty and finality of death: "Death,in itself, is nothing; but we fear to be weknow not what, we know not where," saysthe Indian hero of John Dryden's heroicplay Aureng-Zebe (1675).

War, famine and plague were commonoccurrences for people then: for instance theThirty Years War devastated the German-speaking areas of Europe between 1618 and1648, and plague ravaged London and manyother cities in 1665. A few years later, HansJakob Christopher von Grimmelshausen, aGerman soldier who had served in that war,produced one of the masterpieces of baroqueprose fiction, a novel called Simplidssimus,which has been translated into many lan¬guages and which expresses its author's first¬hand experience of prosperity and adversityin a fascinating fusion of narrative forms andstyles ranging from the picaresque traditionof the Spanish satirical novel of low life to thefashionable courtly romance in which thehero's adventures finally turn out to have anunderlying design and purpose.

In various parts of Europe men were gaz¬ing heavenward at the mysteries of a universewhich was growing daily vaster thanks to thenewly invented telescope, and trying tocomprehend the harmonies which theyknew must underlie it. Kepler's scientificemphasis on elliptical motion, and his obser¬vation that the heavenly bodies can formconstant patterns despite the fact that theyare never static, have many features in com¬mon with the restless movement, the ellipti¬cal shapes and the formal designs whichunderlie all baroque architecture, art and lit¬erature. The recognition of fundamentallaws and transcendental order made it possi¬ble for them to accept that this brief andfragile life of ours, this vale of tears, is a mereillusion, yet prevented them from lapsinginto dark despair at the inevitable fact ofmortality. Even in the delightful innocentpastoral world of Arcadia, peopled withpretty nymphs and love-lorn shepherds,which baroque writers never tired of evok¬ing, death could never be entirely ruledout.

But it was not of death, perhaps, thatbaroque writers most complained, but ofTime, under the fatal shadow of whose

wings all things decay and wither. The cen¬tury which saw the invention of the pen

dulum clock and the balance-spring mecha¬nism in watches was growing more and moreaware of the passing of time of time mea¬sured not just in seasons, months and days,but in hours, minutes and even seconds. The

pressure which all modern people knowcame as something of a shock to the seven¬teenth century. To own an hour-glass orpocket-watch was a first step towards theacute consciousness of fleeting time whichquickly became a major preoccupation of theperiod. It became a frequent theme forpoets, and in some more thoughtful writersit was to engender a feeling of metaphysicaldread.

But the acute awareness of rapacious timeforever slipping by and taking with it all thethings we love and value most; the universalsense of the vanity of all earthly things whichpoets and preachers reiterated in all thecultural languages of Europe; the tombalways waiting just around the corner as areminder that flesh is mortal and that man is

dust: all this paradoxically led to an extraor¬dinary capacity for living and enjoying life.This paradox is to be found at the heart ofcountless baroque poems in which poetsencouraged men and women to gatherrosebuds while the summer lasted, to love

one another and to be in love, and to appreci¬ate the colourful masquerade of life. Theirknowledge that it would all end like a dreamserved to put life in perspective and toenhance its value for those on whom fortune

smiled. Famous examples are to be found inall the literatures of Europe: in John Donneand Herrick, in the French poet Ronsard'sadmirers Hooft and Opitz in the Nether¬lands and Germany, and in the complex and

Pain and suffering are frequently portrayed inreligious drama, painting and above aü sculp¬ture of the baroque age. Spanish baroque reli¬gious carvings are particularly notable for theirsometimes macabre depictions of Christ, theVirgin Mary and other figures of the Passionstory in paroxysms ofgrief. Below, the severedhead of St. John the Baptist (c. 1625) by theCordobán sculptor Juan de Mesa (Sevillecathedral).

The works ofShakespeare (left), while not strict¬ly speaking baroque, often reflect the spirit ofthe age in their explosive violence and in theirpreoccupation with appearance and reality andwith dramatic illusion. The SpanishpoetLuis deGóngora y Argote (centre) was a master of ahighly ornamental, labyrinthine style which be¬came known as "gongorism". Like its Italianequivalent "marinismo" (named after the Ita¬lian Giambattista Marino), it echoed contem¬porary trends in the plastic arts. Engraving,bottom left, is the frontispiece illustration of a17th-century edition of Simplicissimus, a'mas-terwork ofbaroqueprose by the German writerGrimmehhausen.

jfoaiiUT.mnriT i tnuiram u ""VrrT

'3.'¡."-vii.- ,Vr r tr: "*

MWm

sophisticated verse of Marino in Italy andGóngora in Spain.

Despite its emphasis on the transience ofall earthly things, baroque culture producedworks of literature which can attain

unparalleled vitality and intensity. But thisonly becomes fully evident if one can under¬stand the meaning of the words in whichbaroque poems, plays and novels are writ¬ten and sometimes their hidden meanings,too ! Otherwise, the rich interplay of images,metaphors and conceits which baroquewriters delighted in inventing may some¬times seem to readers today to amount tononsense.

Only in performance can baroque playsand operas capture our whole attention andenthral us with their sights and sounds, theirappeal to ear and eye, the mind and the imag¬ination. Yet performances are rare, and mostof them have to take place in the imagina¬tions of sympathetic readers or of listeners torecordings. Only when we are actuallystanding in the baroque churches and palaceswhich can be found all over Western Europeand in many of its former overseas colonialpossessions can we come to appreciate thepowerful claims that the Baroque makes onus.

Modern readers and spectators may thinkthat much is fake: they may find it as hard torelate to the far-fetched metaphors and floridsentiments expressed by baroque love poetsas to the exaggerated poses of carved andpainted statues. But sometimes, even now,we can still register the impact of a lovesonnet or a funerary ode, a heroic tragedy ora deftly turned comedy, and marvel at theaudacity with which these artists three cen¬turies ago reflected a world not yet deprivedof its sense of delight and wonder and gaveexpression to Europe's last comprehensivevision of a universe not yet bereft of itsdivinity.

PETER SKRINE, of the United Kingdom,teaches German language and literature at theUniversity of Manchester, and specializes in thepoetry and drama of the seventeenth century. Hehas written many articles on these and other sub¬jects and is the author of a book on seventeenth-century literature and culture in Europe, entitledThe Baroque (Methuen, London and New York,1978).

Rubens

the magnificentWhile baroque art did not take root in thenorthern Netherlands, it blossomed in the south

(what is now Belgium) above all in 17th-centurypainting. Baroque art is at its most luminous andsensual in the work ofPeterPaulRubens, whichcelebrates life in all its forms. Through Rubens,who knew Italy well and paid a long visit toSpain, Antwerp became a centre ofthe artsfromwhich a taste for baroque painting spreadthroughout Europe. Right, The Last Judgment(1616), a work by Rubens which is today pre¬served in Munich. Compared with the workwhich inspired it, Michelangelo's Last Judg¬ment in the Sistine Chapel, Rubens' paintingappears typically baroque by virtue of the ex¬aggerated dynamism of its figures and the vio¬lent effects of contrast.

*

'#'

tf

#

Three great domes BY GIULIO CARLO ARGAN

St. Peter's basilica, Rome, with the colonnade

designed by Bernini flanking the square

St. Paul's cathedral, London The church of St. Louis des Invalides, Paris

IF Roman Baroque is the representationof a religious and political ideal, FrenchBaroque is the representation of an

exclusively political ideal, and EnglishBaroque that of a civic and social ideal. Thediversity of the ideological content ofFrench, English and Italian Baroque is strik¬ingly illustrated by a comparison betweenthe three famous domes of St. Peter's in

Rome, the church of St. Louis des Invalides

in Paris, and St. Paul's cathedral in London.

The first is clearly the archetype. In thethinking of its architect, Michelangelo, laterfollowed and given a wide allegorical sweepby Bernini in his conception of the colon¬nade flanking St. Peter's Square, the domewas ta be identified with the body of thechurch, to be the image of the head of Chris¬tianity and of the celestial vault which ideallycovers the whole ecumene (the world). InBernini's design, the wings of the colonnadeare like the arms of a figure whose head is thedome.

Resting on a double drum, Jules Hard-ouin Mansart's dome in Paris rises in sov¬

ereign isolation above a flat façade dividedby columns into geometrical panels: its massand its ornate decoration dominate the

whole building, supported on a perfectarchitectural arrangement just as the sov¬ereign power was supported by the hier¬archical order of the State of which it was the

summit.

Christopher Wren's dome in London isrelated, through the Italian architect Sebas¬tiano Serlio, to Donato Bramante's originalplan for St. Peter's. It rests on a vast edificewith which it is so little articulated that it

requires a cylindrical base. It is like a build¬ing incorporated into another building andonly distinguished from it by the stylizedelegance of the drum and the curvature of thedome. This dome is more of a symbol thanan image of power; and its function is purelyformal, like that of the sovereign in theEnglish political structure of the late seven¬teenth century. Without going so far as tosee a deliberate political allegory, it must beremembered that the form of a dome tradi¬

tionally symbolizes authority or power andthat such a political intention is surely at theorigin of Michelangelo's dome and inspiredthe domes of Mansart and Wren.

GIULIO CARLO ARGAN, Italian art histor¬

ian, is a professor at the University of Rome andwas mayor ofthe aty from 1976 to 1979. He is theauthor of many works on art history, urban plan¬ning and methods of criticism, including the bookfrom which this article is taken, Immagine e per-suasione. Saggi sul barocco (1987) and, publishedin English, The Renaissance City (Braziller, NewYork, 1969).

The musical offering BY ALBERTO BASSO

Opera, one of the most characteristic forms ofbaroque musical expression, originated in Italywith Orfeo, L'incoronazione di Poppea andother landmark works by Claudio Monteverdi.The first significant French operas were writtenby the Italian-born musician Jean-BaptisteLully, whose influence extended throughoutEurope. Above, "The Fall ofPhaethon ", a stagedesign by Jean Bérain the Elder for Lully 'smusical drama Phaeton.

IN music, the term baroque has beenused to describe a certain concept of art,a stylistic idiom, but also a method of

composition built on a specific component,the basso continuo. Described in simpleterms, such compositions consist of amelodic line and a continuous accompani¬ment in a set form. This type of compositionis quite different from that of the precedingperiod, when the emphasis was placed onpolyphony, that is, music in which there areseveral parts of equal importance.

The starting point of the new epoch isusually taken as the year 1600, when theItalian melodramma (opera) came intobeing, and its end is generally considered tohave come with the death of Johann Sebas

tian Bach in 1750. The history of musicunderwent extraordinary changes in thiscentury and a half during which forms thatwere to exist for hundreds of years were"invented", and the structure of harmonywas established on foundations that lasted

into much later times.

As the Renaissance drew to a close, one

outstanding event dominated the musicalworld, and later had a far-reaching effect onthe development of style in literature, in thepictorial arts, in architecture and even insocial life. This was the rise of opera, thelogical evolution of the revival of the art oftheatre which was ushered in by the Italiancourts and was the outcome of the Renais¬

sance desire to recreate classical Antiquity

11

and actualize Hellenistic civilization. Operaoriginated in Florence, but acquired variouscharacteristics of style and expression inRome, Venice and Naples. It was the mosteffective vehicle of the new musical culture

in Italy, and rapidly won recognition inother countries, where it almost alwaysretained its original character, except inFrance where it developed independentlyand was known as tragédie lyrique.

Claudio Monteverdi, Luigi Rossi andFrancesco Cavalli were the leading expo¬nents of this new genre in the early seven¬teenth century, while later Jean-BaptisteLully (the Florentine who was the father ofFrench opera) and Alessandro Scarlatti cameto the fore as creators of two different kinds

of musical theatre that persisted throughoutalmost the whole of the eighteenth century.

The operatic style that prevailed was thatof Scarlatti, which was taken as a model even

by German masters such as Handel andHasse. Opera was originally a "serious"genre, but later it assumed a comic form aswell, and became either a theatrical produc¬tion in its own right or a kind of humorousinterlude performed between the acts of alarger production (as in the case of the inter¬mezzo, the undisputed master of which wasthe Italian composer Giovanni Battista Per-golesi). In other countries opera gave rise to

entertainments in which spoken dialogueand singing were combined (the Englishmasque, the Spanish zarzuela, the Frenchopéra-comique, the German Singspiel),which supplanted the traditional Italian pat¬tern of recitative and aria.

This same pattern also dominated otherforms of vocal music, above all the oratorio,

the authentic expression of the devotionalspirit of the Counter-Reformation whichhas all the characteristics of a spiritual operawithout scenery. At least, this is the casewith the most typical, vernacular form oforatorio, such as the splendid works ofStradella and Alessandro Scarlatti, for those

written in Latin (mainly associated withCarissimi) were more ecclesiastical inspirit.

Unlike oratorios, which usually relatebiblical events or the lives of the saints, Pas¬sion music centres on the death of Christ and

often uses the words of the Gospels. Thefinest examples are the Passions of Bach, butother great settings were written byHeinrich Schütz and later by Handel (whowas also a master of the oratorio) and byGeorg Philipp Telemann.

Opera in miniature, the chamber cantata isa typical expression of Italian vocal music.The thousands of examples of this genre sug¬gest that its popularity exceeded even that of

the madrigal in the sixteenth century. One ortwo recitatives and arias were enough tocreate a cantata, and the only instrumentrequired, as a rule, was a harpsichord toprovide the accompaniment. From Car¬issimi to Rossi, from Cesti to Stradella, from

Pasquini to Scarlatti and Handel, the cantataremained in vogue throughout the baroqueperiod, even in French musical circles,which constantly resisted the Italian style.Indeed, the opposition between Italian styleand French taste was one of the most

persistent and pervasive features of thebaroque era.

As for sacred music intended for use in the

liturgy, masses and motets continued to becomposed, although at a rather sluggish rate.The great masters of sacred music belongedto the Roman and Venetian schools (Benev-oli, Bernabei, Caldara, Gasparini, Legrenzi)and then the Neapolitan school (Scarlatti,Durante, Leo), later being drawn from theGermanic countries, (Biber, Kerll and Fux)and France (Charpentier, Lalande and Cou-perin). In England, remarkable services andanthems were written for the Anglican'Church by composers who were also notedfor their secular music, such as Gibbons,Tomkins, Lawes, Blow, and above all Pur-

cell, who inspired even Handel.But it was in the Protestant Church music

Developed to a high degree of technicalperfec¬tion, the harpsichord and the organ were, withthe violin, the favourite instruments ofbaroquecomposers. In the work ofGirolamo Frescobaldiin Italy andJohann Sebastian Bach in Germany,organ music reached its peak, while in FranceFrançois Couperin "the Great" won fame as thecomposer of music for the harpsichord. Eight¬eenth-century engraving, left, shows the decora¬tion of the organ in Weingarthen Abbey inSwabia (Fed. Rep. of Germany) built by Gablerin 1750. Below, "A Lady Playing a Spinet", anengraving by Bonnart (c. 1685). An earlykeyboard instrument of the harpsichordfamily,the spinet was widely played in the 16th and17th centuries, especially in England.

12

From Monteverdi to Bach

which sprang from the Lutheran Reforma¬tion that the baroque period revealed a newsensibility. The sacred cantata, more oftencalled a sacred concerto or simply a concerto(as if to emphasize that it was the descendantof the Italian concerto ecclesiastico, a com¬

bination of voices and instruments), came toplay an essential role in worship, andinspired a constant creative effort from com¬posers. The words were taken from theScriptures, often from the readings pre¬scribed by the liturgical calendar for feast-days, and the music took over that extraor¬dinary vehicle of artistic and religious feel¬ing, the chorale.

Schein, Scheidt and Schütz (the three greatSs of the history of German music) laid thefoundations of an edifice that was to include

composers such as Buxtehude, Pachelbel,Tunder, Weckmann, Böhm, Theile, and

above all Bach and Telemann (the latterwrote almost 1,600 liturgical cantatas).Bach, however, was the great exponent ofthe religious cantata. (He is thought to havewritten some 300, a third of which are lost.)His works, which span the whole baroqueperiod, constitute an unrivalled repertory ofthe vocal and instrumental techniques usedto express the emotions aroused by sacredtexts and religious festivals.

Some of the greatest works of instrumen¬tal music, whether for a solo instrument or

an ensemble, are associated with the baroqueperiod. Pride of place went to keyboardinstruments (harpsichord, spinet, virginals,clavichord and organ), with a repertoire thatwas often interchangeable. The work of theItalian school of organists reached its peakwith Girolamo Frescobaldi, whose organmusic and style influenced the whole ofEurope. One of his most distinguishedpupils, Johann Jakob Froberger, spreadthroughout the Germanic countries a mes¬sage that was heard above all by the mastersof the southern school, whose greatest figurewas Pachelbel. The northern school, on the

other hand, was more vigorous and pro-

Shown above are portraits of some of the greatcomposers who contributed to the flowering ofbaroque music, which began with Monteverdiin Italy at the beginning of the 17th century andended in the first half of the 18th century withBach. 1. Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), com¬

poser of operas, madrigals and sacred music,whose work had a seminal influence on modemmusic. 2. François Couperin (1668-1733), theFrench master of the harpsichord, as depicted inan anonymous portrait at the Palace of Ver¬sailles. 3. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750),one of the greatest musical geniuses ofall time,(engraving afterapainting by Gebel). 4. GeorgeFrederick Handel (1685-1759), another greatGerman composer, who spent much ofhis life inEngland (engraving after a painting by G.F.Schmidt). 5. The Italian composer AlessandroScarlatti (1660-1725). His son Domenico, aharpsichord virtuoso, livedfor manyyears at theSpanish court, and taught Antonio Soler, theleading Spanish baroque composer. 6. HenryPurcell (1659-1695), the English composer whoin his short life wrote some of the finest lyricalmusic of the age.

1 . Photo © Cournat © Rapho, Paris2. Photo © Ciccione-Bulloz, Paris3. Photo © Bulloz, Paris. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris4. Photo © Bulloz, Paris. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris5. Photo © Roger Viollet, Paris. Museo Cívico, Bologna6. Photo © Edimedia, Paris. British Museum, London

duced more illustrious figures, notably Bux¬tehude. It claimed as its progenitor a Dutchmaster, Sweelinck.

Toccatas, fantasias, preludes, Capriccios,ricercars and fugues proliferate in the key¬board music of the time. Dance rhythmswere adapted into suites incorporating styl¬istic, metrical and dynamic variation. TheLutheran liturgy gave scope for the develop¬ment of another genre, the choral prelude fororgan, which extended the range of thatinstrument by providing it with a repertoireof incomparable splendour, which will for¬ever be associated with the name of Bach.

Among the illustrious names linked withthe harpsichord are those of Frescobaldi andMichelangelo Rossi, and later Pasquini,Alessandro Scarlatti and his son Domenico,

Couperin and Rameau, Bach and Handel.But the harpsichord was also used to accom

pany instruments on which the melody wasplayed, especially the violin, the repertoirefor which culminates in the sonata and the

concerto, the two great ideal forms of thebaroque period, whether composed aschurch music or as chamber music. Later,

the development of the concerto followedtwo paths: that of the concerto grosso (inwhich a group of solo instruments is heard incontradistinction to the whole orchestra, the

tutti), and that of the concerto solo (in whicha single instrument accomplishes impressivefeats of virtuosity).

Arcangelo Corelli was the forerunner ofgenerations of violinists, but with him werethe greatest exponents of Italian eighteenth-century instrumental music Vivaldi,Albinoni, Geminiani, Locatelli, Tartini,Torelli, Marcello. Hundreds of works for

solo instruments or groups are evidence ofan incomparable vitality which was felt inevery country in Europe, for their compos¬ers bore the Italian style far beyond the bor¬ders of Italy.

Meanwhile, new musical forms were

being developed. The symphony and over¬ture vied with each other in a field teemingwith ideas, and compositions graduallybecame increasingly complex and moreheavily orchestrated. The basso continuoacquired a personality of its own, as severalthemes were introduced into the fabric of the

music, which was composed in accordancewith dialectical principles. From then on therich, mannered baroque style began to giveway to the elegant and graceful style galant.

ALBERTO BASSO, Italian musicologist, waspresident of the Italian Musicology Society from1973 to 1979. He is the author of several booksincluding a six-volume history of music and abiography of Johann Sebastian Bach. He is atpresent editing an eight-volume Dizionario encic¬lopédico universale della música e dei musicisti("Universal Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Musicand Musicians").

13

An art ofgilt andpathos BY JULIAN GALLEGO

Above, the monumental baroque façade knownas the Obradoiro, which was added to the

romanesque cathedral of Santiago de Compost-ela (Spain) in the 18th century. Gothic andplateresque (Spanish Renaissance) elements arealso found in the cathedral.

IT should be said at the outset that

religion played a fundamental role in thedevelopment of Spanish Baroque. We

shall not go into the question of the meaningof the term baroque, still less considerwhether, as the Spanish critic Eugenio d'Orshas claimed, it is a cultural constant, recur¬ring throughout the history of art in dif¬ferent periods and forms, in alternation withclassicism.

In his book Principles of Art History, theSwiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin

broadly defined "classical" and "baroque" asstatic and changing forms of art respectively.In another influential book, Baroque, theArt of the Counter-Reformation, by WernerWeisbach, the Baroque is seen as a passio¬nate reaction against Renaissance paganism.

Some specialists have recently suggestedthat there is an intermediate style known asMannerism, which did not commit the

rhythmic and decorative excesses of theBaroque but did reject the balance of theRenaissance in an endeavour to achieve

heightened emotional effects (the mostrenowned example of this style is perhapsMichelangelo's LastJudgment, in the SistineChapel, Rome). Some scholars consider thatMannerism is the true art of the Counter-

Reformation, and the Spanish critic JoséCamón Aznar has suggested that the term"mannerist" should be replaced by "tren-

tine" (after the Council of Trent, which cod¬ified the principles of the Counter-Reforma¬tion).

The monastery of San Lorenzo delEscorial, one of the outstanding monumentsof Spanish architecture, is an example of thisstyle. It was built near Madrid between 1563and 1584 on the orders of Philip II. Its archi¬tects were Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juande Herrera, the latter of whom gave his nameto the "herrcran style". Characterized byausterity, clarity of line and volume, and anattachment to regular, geometrical forms,the style of the Escorial was to influence thedevelopment of Spanish architecturethroughout most of the seventeenth century,and remained a model until it was supplantedin the eighteenth century by the highly orna¬mental "churriguercsque" style, which took .its name from that of a family of architects,the Churrigueras.

Most ecclesiastical buildings in the Span¬ish baroque style were built to rectilinearplans until well into the eighteenth century,and innovations were confined to ornamen¬

tation. Many churches were built to a planderived from that of II Gcsù in Rome, the

mother church of the Society ofJ esus, whichhad been founded by the Spaniard IgnatiusLoyola. The plan of II Gcsù is cruciform,and there is a dome above the crossing of thetransepts and the nave. On each side of the

14

nave there is a row of chapels. There are alsoexamples of vast oblong churches, whosearchitectural sobriety contrasts with theirabundant, showy decoration, in wood andplaster, sometimes stone and metal. Iron¬work is rich and abundant, and the chapelsusually have wrought-iron gates. The deco¬ration of the upper part of the church maytake the form of stalactite-like shapes andother ornamental relief carvings of the typedescribed technically as "Grotesque". Insome cases these are vestiges of the mudejarstyle of Muslim Spain (al-Andalus) whichlasted from the eighth century until the endof the fifteenth century.

The lower part of the walls is often cov¬ered with altarpieces in the form of a tri¬umphal arch with richly decorated columnsand pediments. The largest altarpiece, in theapse, is a monumental structure whichreaches to the vaults and is usually entirelycovered with gilt and polychrome painting.In the church of San Esteban in Salamanca is

a massive altarpiece designed by José deChurriguera (1668-1725). It has six hugetwisted "Solomonic" columns, modelled on

a column in Rome which was supposed tohave been part of Solomon's temple; thisform became famous when Bernini used it

for the baldacchino, or ornamental canopy,over St. Peter's tomb (see photo page 5).Supports of this kind (which sometimes sup¬port nothing) bring dynamism to porches,chapels and shrines, of which there are manyremarkable examples in Andalusia. Theydisplay the influence of the new architecturefrom Latin America, for while Spanish mod¬els were dominant in Spain's American colo¬nies, they were influenced by the taste andcraftsmanship of the indigenous peoples(especially in Mexico and Peru) and gave riseto a colonial Baroque whose luxuriant orna¬mentation and colours in their turn influ¬

enced the Baroque of metropolitan Spain.The great Spanish court architect was

Pedro de Ribera (c. 1683-1 742), whose workshowed a pronounced taste for the theatri¬cal. As supports he used "estípites", highlydecorated pilasters of irregular shape, whichhad been introduced into Madrid architect¬

ure by José Ximénez Donoso (1628-1690).Thus, although the Bourbons succeeded theHouse of Austria as rulers of Spain, the clas¬sical baroque style of Versailles was notadopted at the Spanish court until the royalpalace in the Alcazar (the style of which wasmore or less herreran) was destroyed by firein 1734 and was replaced by the Palacio deOriente, the work of the Italian architects

Filippo Juvarra and Giovan Sacchetti, inwhich there is less typically baroque orna¬mentation. The outstanding example of thistransition to classicism is the architect Ven-

Right, the Baptism of Christ by El Greco (1541-1614), the great Cretan artist who settled inToledo. Baroque sensibility is apparent in thedramatic upward movement and bold elonga¬tion ofnaturalforms characteristic ofEl Greco 'slate works.

tura Rodríguez (1717-1785), whoredesigned the Paseo del Prado, which madeMadrid one of the great European capi¬tals.

In Andalusia, the vitality of the Baroqueleft its mark on churches, monasteries and

convents, and palaces, in which fantasy andelegance are combined in the use of multi¬coloured materials such as brick, various

kinds of stone, glazed tiles, carved wood,forged iron-work, shutters and stucco. Ofspecial interest are tall, decorated bell-tow¬ers such as that at Ecija, and elegant bell-gables, examples of which are found inSeville and Cadiz. Inside the highly deco¬rated churches there is often a window at a

certain height in the altarpiece, throughwhich can be seen a high chapel or nichewhere a holy image is presented for worship.Most of the external decoration was in por¬ches and cornices; walls were left as

unadorned brick or stone, or were regularlywhitewashed to offer a striking contrast withthe deep blue of the sky.

In Spanish towns and cities a labyrinth ofmedieval streets often leads to magnificentchurch porches or to a plaza mayor, one ofthe great squares which, throughout thepeninsula, are the focal point of civic life andfestivities. The churrigueresque great squarein Salamanca is a notable example. Some ofthese squares are veritable museums of dif¬ferent architectural periods and styles,brought together and unified by baroqueurban planning. One example can be seen atSantiago de Compostela, where the cathe¬dral, which was given the monumental

The monastery ofSan Lorenzo delEscorial, builtnear Madrid between 1563 and 1584 on the

orders ofPhilip II, provided a model for much17th-century Spanish architecture. In the nextcentury the influence of its austere classicismgave way to the highly ornate baroque churri¬gueresque style. Below, the Patio of the Kings,with the façade, a tower and the dome of themonastery church.

baroque façade known as El Obradoiro byFernando Casas y Novoa in the eighteenthcentury, is an extraordinary amalgam ofromanesque, Gothic, plateresque and classi¬cal styles.

Through the combined effect of sculptureand architecture, churches became sacred

theatres opening on to the splendid pro¬cessions that took place outside. Wood carv¬ing was the principal form of sculpture,together with clothed polychrome statueswhich were intended to create a lifelike

effect. The seventeenth-century school ofValladolid, one of the masters of which was

Gregorio Fernández, produced sober, natu¬ralistic works, full of intense emotion. The

people were thus helped to relive Christ'sPassion and death in the Holy Week pro¬cessions. The Andalusian school was more

expansive and exuberant. Its polychromesare brighter, and are combined with richmaterials. In Seville, Juan Martínez Mon¬tañés (1568-1649) and Juan de Mesa (1583-1627) were noted for the brilliant colours

and expressive gestures of their works, andin Granada Alonso Cano (1601-1667),Pedro de Mena (1628-1688) and José deMora (1642-1724) painted works of greatpoignancy. The subjects most frequentlytreated are scenes from the childhood and

Passion of Christ and the motherhood and

sorrow of the Virgin Mary.The eighteenth century saw a trend

towards greater movement and elegance andmore brilliant colours, both in the decora¬

tion of wood (covered with gold leaf, whichwas covered in its turn with oil-paintedembellishments), and in the clothing of stat¬ues with embroidered garments. Toheighten the illusion that they were real andto intensify the sense of drama, statues werefitted out with eyes of crystal, artificial eye¬lashes, and hair. Pedro Roldan (1624-1700)and his daughter Luisa, "La Roldana" (1 656-1704), introduced the new style to Seville,carving widely-admired statues such as thatof the Virgin of Macarena. Smaller statues

The baroqueperiod in Spanishpainting came toan end with Juan de Valdés Leal (1622-1690),whose works are charged with tension and dra¬ma. Above, Valdés Leal's The Wedding atCanaan, now in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

were executed in terra-cotta, a techniqueemployed with great elegance by JoséRisueño of Granada (1 665- 1 757). In Murcia,Francisco Salzillo (1707-1781), an artist ofNeapolitan descent, was renowned both forhis Nativity figures and for groups of elegantand expressive sculptures which could becarried in the Easter procession.

The baroque period is the Golden Age ofSpanish painting. The Andalusian school,which was naturalistic in the Italian style,emerged at the beginning of the seventeenthcentury with Pacheco and Herrera, andfilled the churches with huge canvasses. Thesuccessors of El Greco (1541-1614) workedin Toledo. They did not reach the ecstaticmannerist heights of the Cretan master,whose last works, in their depiction of ver¬tiginous upward movement, verged on theBaroque. Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664), from Extremadura, painted picturesfor altars and cloisters that were imposing intheir archaic sobriety, their tactile andalmost architectural effects, and their piousgravity.

Italian influence can be seen in the paintersof the Valencian school, who were in con¬

stant contact by sea with Naples. Outstand¬ing among them are Francisco Ribalta (1551-1628) and especially José de Ribera, knownas "el Españólelo" (1591-1652), who,though he went to live in Naples and diedthere, influenced painters all over Spain bythe powerful realism and beautiful coloursthat were the hallmark of his work. He sent

his striking paintings of saints and martyrsback to Spain. His example was followed inthe next generation by a pupil of Pacheco,Diego Velazquez (1599-1660), who became

16

painter to King Philip IV. In paintings suchas "The Maids of Honour" and "The Spin¬ners", he displayed a technical skill and aconception of atmosphere and light thatwere completely new and difficult to match,although his successors Mazo, Carreño,Rizi and Claudio Coello are worthy repre¬sentatives of the School of Madrid which he

founded. The artist who most nearlyapproached him was his friend the sculptorAlonso Cano, who was also an excellent

painter and architect. Both these baroquepainters shunned exaggerated attitudes anddynamic movement in favour of serene, clas¬sical perfection, although there is no lack ofenergy in the play of light and the boldnessof the brushwork.

Two Andalusian artists of genius broughtto an end the great period of Spanish baroquepainting: Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682) in Seville, and Juan de Valdés Leal(1622-1690) in Córdoba. These men werenear-contemporaries but differed totally intheir approach. Murillo had a natural gracethat had a wide appeal. He wanted to makethe sacred relevant to his own day; and hehad exceptional technical powers, althoughhis works convey an impression of sim¬plicity. This was the antithesis of the ten¬sions, gesticulations, and exaggerated move¬ments of Valdés Leal, which could,

however, lead to outstanding results in suchpaintings as The Chariot of Elias, in themonastery of the Carmelitas Calzados atCórdoba, a work in which he approaches theRomanticism of Delacroix.

JULIAN GALLEGO, Spanish historian and artcritic, is a professor at the Complutense Universityof Madrid. He is an elected member of the SanFernando Academy ofFine Arts, Madrid, a corres¬ponding member of the Hispanic Society ofAmer¬ica, New York, and a member ofthe InternationalAssociation ofArt Critics. His many publicationsinclude Visión y símbolos en la pintura españoladel siglo de oro ("Vision and Symbols in SpanishPainting of the Golden Age"), Diego Velazquez,and studies on Francisco de Goya and on thehistory of art.

The last phase ofSpanish baroque architecture,known as churrigueresque, is characterized bythe use ofspiralling forms and ornamentation ofa lavishness only surpassed in Latin America.The huge altarpiece by José de Churriguera inthe Dominican church of San Esteban, Sala¬manca (above), is typical of this ornamentalstyle.

Baroque polychrome sculptures of scenes fromChrist's Passion and Crucifixion are found inmany Spanish churches. During Holy Weekprocessions they are carried through the streets.Left, a group ofPassion sculpturesfrom Zamora,a city northwest ofMadrid.

17

Baroque as a worldphilosophyBY EDOUARD GLISSANT

THE baroque style made itsappearance in the West at the verymoment that a certain idea of

Nature that it was homogeneous, harmo¬nious and comprehensible was gainingground. Rationalism refined this conceptwhich fitted in well with its growing ambi¬tion to dominate reality. It seemed, more¬over, that Nature could be artificiallyreproduced, imitation of reality going handin hand with knowledge of it.

Imitation of Nature as an objectiveassumes that, underlying outwardappearance and inherent in it, there is a "pro¬fundity", an unassailable truth, artisticrepresentations of which approximate moreclosely as they systematize their imitation ofreality and discover its rules. The revolutionrepresented by the introduction of perspec¬tive during the quattrocento can thus, per¬haps, be seen as part of the search for thisprofundity.

It was against this current that the baroque"diversion" began to make itself felt.Baroque art was a reaction against therationalist claim to penetrate the mysteries ofthe known in one single, incisive, uniformmovement. The stone with which baroqueart disturbed the rationalist pool was anaffirmation that knowledge is never fullyacquired, a fact that gives it all its value. Thusthe techniques of baroque art were to favour"breadth" to the detriment of "depth".

In its historical context, the baroquediversion thus presupposes a new heroicquality of knowledge, resolutely turning itsback on the goal of attempting to epitomizethe substance of the world in a series of

representative (or imitative) harmonies. Onthe contrary, baroque art or style was to turnto contrast, to circumvolution, to prolifera¬tion, to everything that contradicted the soi-disant oneness of the known and the

knower, to everything that exalted quantityrepeated to infinity and totality eternallyrenewed.

In its historical setting, therefore, baroqueart is a reaction against a natural order, natu¬rally proffered as evidence. When the con¬ception of Nature evolved, at the same timethat the world was opening up to Westernman and that science was bringing the splen¬did ordering of Nature into question, thethrust of baroque art was itself also tobecome generalized, ceasing to be no morethan a reaction. Baroque art, the art ofexpansion, was itself materially to expand.

The first manifestation of this expansionwas undoubtedly to be seen in Latin-Amer¬ican art, so close to Iberian and Flemish

' Baroque, yet so intimately interwoven withindigenous elements, daringly introducedinto the baroque concert. These elementswere no longer seen to enter as revolutionarydisfigurements of reality, but as inputs of anovel kind. No longer simply the negation

of a concept, baroque art has given its sanc¬tion to a new schema (soon to be a newconcept) of Nature, to which it is attuned.

Cross-fertilization is the determinant of

this evolution, and the pursuits of baroqueart are at one with the dizzying adventure ofcross-fertilization of cultures, styles andtongues. With the generalization of thiscross-fertilization, the Baroque has finallyachieved its "natural" condition. It

announces to the world the growing contactbetween a diversity of "natures". It is insympathy with this world movement and isno longer content to be merely a reactionagainst a philosophy or an aesthetic. It is thesum and result of all aesthetic theories, of all

philosophies. In short, Baroque is neither anart nor a style, but a being-in-the-world.

The modern scientific view of reality coin¬cides with and confirms this expansion of theBaroque. Science does, indeed, assert that"reality cannot be defined in terms of outwardappearances and that it has to be examined"in depth", but it also accepts that knowl¬edge is never wholly acquired and that itwould be absurd to claim that its essentials

can be grasped at a single stroke. Science hasentered the era of the uncertainty principle,retaining, nevertheless, a form of rationalismwhich henceforth abjures paralysing,mechanical, once-and-for-all dogmatism.Its conceptions of Nature are "expanding",becoming relative, problematical. It is mov¬ing, that is, in the selfsame direction towardswhich the Baroque tends.

Similarly, human nature is no longerthought of in terms of a clear-cut, universalmodel. The concept of being-in-the-worldimplies the sum total of all types of being-in-society. There is no unique, recognizedmodel. All human cultures have had their

classical periods, eras of dogmatic certaintyfrom which they must all emerge together.In this sense the "profundities" revealed byscience, psychology and sociology countertriumphantly the metaphysical "profun¬dity" emphasized by Western classicismalone. Herein lies the very key to the univer-salization of the Baroque.

One might, then, sum up by saying thatthere has been a "naturalization" of the

Baroque, not simply as an art form or style,but as a way of living out the diversity-unityof the world; that this naturalization takes

the Baroque out of the limited context ofCounter-Reformation flamboyance, ofrevolt against the constraints of a tradition,to give it a universal quality as the embodi¬ment of "interrelating"; and that, in thissense, the Baroque of history foreshadowed,in astonishingly prophetic fashion, theupheavals that mark the world of today.

Finally, a recent characteristic of contem¬porary art, defined by Walter Benjamin as"technically reproducible art", seems toconfirm this movement towards universal-

©

ization. The ability to make exact copies,made possible by modern techniques, haschanged the whole course of future develop¬ment of the arts. Not only has the con¬ception of Nature become relative, thenotion of the metaphysical oneness of a mas¬terpiece has been swept away. In the presentstate of diversity, not only does a work of artcombine profundity with expansion, it isitself subject to a fundamental expansionwhich, thanks to increasingly perfectedmethods of reproduction, adds infinitely toits significance.

EDOUARD GLISSANT, of Martinique, is theauthor of many volumes of poems, novels andessays, including La lézarde, L'intention poétiqueand Le discours antillais. He has also published aplay, Monsieur Toussaint. In 1967 he founded theInstitut Martiniquais d'Etudes at Fort-de-France.Since 1981 he has been editor-in-chief of the Un¬esco Courier. His latest novel, Mahagony, has justbeen published.

Although the notion of the Baroque is primarilyassociated with a specific period in the culturalhistory of the Christian West, the 17th and 18thcenturies, some writers have wondered whether

it could not be applied in afar wider context todescribe a surge ofvitality, movement and emo¬tional force of the kind which periodicallycauses an upheaval in the arts. The Spanishcritic Eugenio d'Ors has suggested that theBaroque may be an essential component of in¬telligence and sensibility, a "stylistic constant"which recurs throughout history. Such a thesiscould help to explain the affinities that can beobserved between Western Baroque and otherforms ofartistic expression that have appearedat different periods in countries far distantfromeach other. 1. 13th-century Gate of Victory inthe temple complex of Angkor Thorn, Kam¬puchea. 2. Church ofthe Sagrada Familia (HolyFamily), Barcelona, by the Catalan architectAntonio Gaudt, begun in 1883 and never com¬pleted. 3. Tomb built for himself by FerdinandCheval, French postman and self-taught artistfamed for the "Ideal Palace" he built (afterseeing it in a dream) between 1879 and 1912 atHauterives, Drame, France. 4. Colourful car¬nival scene from Trinidad and Tobago (WestIndies). 5. The Cuban poet and novelist JoséLezama Lima (1910-1976) who, like manyLatin American writers, considered himself abaroque author, and claimed affinities with theSpanish baroque poet Góngora.

18

The baroque impulse

19

Sculpture, theatre of the sublimeBY FRANÇOIS SOUCHAL

The genius of Bernini, the supreme artist ofbaroque Catholicism and the man who made St.Peter's basilica the prestigious centre of thepapacy in Rome, was expressed with thegreatestintensity in his work as a sculptor. Above left,The Ecstasy of St. Theresa (1644-1652) in theCornaro chapel in the church of Santa Mariadella Vittoria, Rome, a dramaticportrayalofthemystic rapture of a 16th-century Spanish nun.Bernini sought above all to express movement insculpture, often with a dynamism which infusedreligious fervour even into works on mytholo¬gical themes such as Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625) in the museum of the Villa Borghese,Rome (above right).

PROJECTING matter into space,delimiting its presence there, thesculptor's art is both defiant and sym¬

bolic. Drawing its vitality from a constantstate of tension with the architecture that

provides both its frame and its support, it hasto assert its identity within its environment,and derives from this necessity a measure ofits dynamism and its dignity. Essentially,primordially, an act of artistic creation,sculpture also bears a message: its image of adivinity, a sovereign or simply of a man isnever entirely gratuitous.

At the close of the sixteenth century, thesculptor's unremitting struggle with naturehad led him into an impasse. Michelangelo,assailed by doubts, left his statuesunfinished. Mannerism turned in on itself,

caught up in convolutions of its own mak¬ing, a serpent swallowing its own tail. In thisatmosphere of introspection, the only possi¬ble outcome was escape or asphyxia. West

ern art, as it had so often in the past, rose tothe challenge. Gathering new strength in theprocess, it would give consummate expres¬sion to the civilization that emerged from thegreat conflicts of the sixteenth century.Although this civilization was restless andprecariously balanced, it lasted for two hun¬dred years.

It would be absurd, spurious even, toattempt to list in order of importance thedifferent modes of artistic expression thatcharacterized this baroque civilization.However, its great master was unquestiona¬bly the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini(1598-1680), an artist who was perhapsunsurpassed in the skill with which heinstilled living movement and the force ofillusion into his works. The personality ofBernini is so overwhelming, so fascinating,that it is tempting to see him as the person¬ification of the magic spell that Baroque wasto cast over all Europe for generations.

20

However, it should not be forgotten thatBernini himself was plagued by contradic¬tions; he was an ardent, passionate man, butone who took Antiquity as his yardstick andnever ceased to be haunted by the greatvision of classical harmony. Nor is it possi¬ble to overlook the forces of oppositionwhich were inspired by rivals such as theItalian Alessandro Algardi and the FlemingFrançois Duquesnoy, and which, through aconcern for simplification have been identi¬fied with an "anti-Baroque" and con¬sequently "classical" movement. But sim¬plification can often lead to a degree ofmisapprehension, if not to outright error. Itis not false to say that one of the riches ofsculpture in this period lies in the dialecticaltension between Baroque and classicism. Itis equally true that Baroque was a complexart whose very complexities undeniably addto its riches. And perhaps it is an example ofan art form that contained deep within itself,embedded in an awareness of its own limita¬

tions, the reasons for its eventual decline and

demise, firstly because it is an art thatdepends on immediacy, on capturing move¬ment at the crucial moment, and secondlybecause it is a theatrical, self-contemplatingart, and is thus sometimes charged withalmost unbearable emotion the emotion of

pathos rather than tenderness.Let us look first at Bernini's famous sculp¬

ture The Ecstasy of St. Theresa, whichprovoked such sardonic laughter on the partof the French scholar Charles de Brosses

(1 709-1 777). In this work in a side-chapel ofthe Roman church of Sta. Maria della Vit-

toria, Bernini has arrested the flight of thegolden arrow in the split second before itpierces the heart of the saint and mystic,capturing, in the same split second, theexpression of ecstasy that illuminates herfeatures. Meanwhile, at the crucial moment

in this celebration of Christian spirituality,the members of the Cornaro family, towhom the chapel belonged and who are por¬trayed on each side of the composition inniches that bear a remarkable resemblance to

boxes in an opera-house, gossip away in sub¬lime indifference to the beatific vision that is

taking place before their eyes.In its force of contrast, ambiguity, illu¬

sion, illusionism even, this is undoubtedly amasterpiece of baroque sculpture, simul¬taneously expressing intense religious fer¬vour and the worldliness of a society thatlived as if it were on stage and believed thattheatre was more real than life itself. In this

work of art in which stage effects figureprominently, light falls mysteriously from ahidden source, softened by coloured filters,and lends its own glory to the wonderfulgroup that occupies space with suchassurance and such power (of fascinationrather than persuasion) that the question ofdomination by or subjection to its architec¬tural framework does not arise.

Nor should it be forgotten that Berniniwas also outstanding at the staging of funeralscenes and spectacular ceremonies. Hissculpture was designed to entrance the spec¬tator. Even when he takes a subject from

classical mythology, as in the Apollo andDaphne at the Villa Borghese in Rome, thetransformation (in this case of the nymph'snubile body into a laurel tree) is designed toprovoke stupefaction, a shudder of amaze¬ment. This is why the baroque sculptorfound equal fulfilment in depicting Christianmiracles and Ovidian metamorphoses: bothreflected the same appetite for the mar¬vellous.

The taste for the supernatural wasexpressed with particular gusto in the Ger¬manic world, the home of Bernini's most

faithful disciples and a place where Natureand reality had already in the past been sub¬jected to violent distortions in the name ofart. In the church at Rohr, the painter Cos-mas Damián Asam and his brother, the

sculptor Egid Quirin Asam, boldly staged (atheatrical term, again!) one of the Christianmysteries, The Assumption of the Virgin. Inthis work executed in plain and polychromestucco, the Mother of Christ is suspended inmidair, in defiance of the laws of gravity.The gestures and facial expressions of theApostles gathered around the open tombreveal a variety of reactions to this new chal¬lenge to reason. They are actors in a tragedy,playing their roles with passionate convic

tion. And we feel, as we do before the works

of Bernini, how these great baroque sculp¬tures reflect an authentic sincerity and inten¬sity of faith, a piety that proceeds not fromintrospection but rather from a warm andoutgoing desire to communicate, from animpulse towards charity, from confidence inGod's infinite goodness and in divine grace(here is the language of mysticism again!).

Baroque sculpture did not, however, limititself to the depiction of superbly performedgreat moments of sacred theatre. True, it is aproduct of religious fervour, and is the lastsacred art worthy of the name in the Chris¬tian West. But baroque society was also thereflection of a system of government of amonarchical system that was more or lessabsolute according to the traditions and pat¬tern of development of each State. Andbaroque sculpture, if it served the Church,

The Ganges, a detail of Bernini's Four RiversFountain (1647-1670) which adorns the centreof the Piazza Navona in Rome. Bernini, Borro-mini (the architect of the Piazza Navona) andGuarini were the great trio of Italian baroquearchitects.

21

: &m

© Baroque at Versailles

The 17th century in France is often seen as theage of classicism. The French painters of theperiod, including the greatest of them, NicolasPoussin, seem to have been largely untouched bybaroque vehemence. Even the Palace of Versail¬les, the masterpiece of the reign of Louis XTVdesigned by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, Louis LeVau andAndré Le Nôtre, appears at first to be aclassical work by virtue of its plan, with itsbuildings and gardens reflecting a concern forgeometrical balance far removed from baroquesinuosity. Nevertheless, Charles Le Brun, whowas commissioned to decorate the palace byLouis XTV in 1674, enriched it with many baro¬que scenic elements. Above, The Chariot of theSun fry Jean-Baptiste Tuby. This gilded bronzesculpture in the Bassin d'Apollon, in thegardensof the palace, was executed from a plan by LeBrun.

also served this monarchical and aristocratic

society, providing a necessary setting for theceremonial and liturgy of kings and princes.On the façades of palaces, on the walls ofreception rooms, lining the paths that ledthrough parks and gardens, forming the cen¬trepiece of ponds and fountains, baroquesculpture proclaimed the virtues of a politi¬cal system that would only begin to crumblemuch later, under critical assault from the

philosophers of the Enlightenment.Baroque sculpture adapted itself equally

well to each of the two prevailing codes ofexpression: Biblical Christian iconography,and mythology as it had been formed bywriters such as the Italian Cesare Ripa (1560-1645) into a more or less coherent symbolicsystem. With the exception (by no meansabsolute, however) of portraiture, allegoryis sovereign and ever-present in baroquesculpture. Mythological figures are enrolledas actors to give some kind of demonstra¬tion. Sometimes, too, allegory is given formand movement without the support ofmythology.

The French tend to reject the epithet

"baroque" as a description of the great sculp¬tures that adorn the park of Versailles. Butwhat could be more profoundly baroquethan this universe of marble and lead, repre¬sentation of a veritable political cosmogony?It is true that the performers in this particulardrama are somewhat less exuberant than

their Italian or German counterparts.Restraint is a feature of French theatre. And

more intellectual concerns are evident in this

remarkable commission dating from 1674,the product of the imagination of the painterCharles Le Brun and of the talent of the

sculptor François Girardon and his disciplesand rivals. The completed work depicts anastonishing tetralogical system: the four sea¬sons, the four humours, the four times of the

day, the four forms of poetry, and so on.This is an eminently baroque attempt to

sum up the world of knowledge and knowl¬edge of the world. The mode is secular, butthe ambition is equal to that of the greatreligious compositions. Here once again isthe ambiguity of baroque sculpture heraldof the irrational and the pathetic, yet astaunch defender of comprehension andrhetorical unification, despite its excessesand emotional turbulence and thanks to its

transcendent spirit and its pursuit of the eter¬nal. Baroque sculpture is the most deter¬mined attempt to give expression to the pas¬sion that moves men and lifts them to the

sublime.

FRANÇOIS SOUCHAL, French art historian

and museum curator, has been professor of thehistory of art at the university of Lille since 1969.He is a member of his country's Historic Monu¬ments Commission and the author ofmany articleson baroque sculpture and architects. Among hispublished works are three volumes in English enti¬tled French Sculptors of the 1 7th and 1 8th Centur¬ies (Faber & Faber, 1977-1987).

COLOUR PAGES

Colour page right

Above left: head of a thief, detail of apolychrome wooden statue (1796-1799) carvedby Antonio Francisco Lisboa, known as O Alei-jadinho (the Little Cripple), for the Way of theCross series in the sanctuary of Bom Jesus deMatozinhos at Congonhas do Campo, Brazil.(See article page 39.)Photo © SCALA, Florence

Above right: Presentation of Christ in theTemple (1641) by the French artist Simon Vouet(1590-1649). Vouet was one ofthefirst artists tointroduce an Italianate baroque style ofpaintinginto France, along with Charles Le Brun, de¬corator of the Palace of Versailles.Photo © D. Genet, Editions Mazenod, Paris. Louvre Museum

Below: the great ceiling fresco in the PalazzoFarnese, Rome. The fresco, on mythologicalthemes, was painted between 1597 and 1604 byAnnibale Carracci (1560-1609). This master¬piece of 17th-century Italian art was a majorinfluence on the development ofbaroque paint¬ing and decorative arts. (See article page 30.)Photo © SCALA, Florence

22

'**

^gj'c kB^JE

^

.

sc

.1

i i 3

«y> jsi

.XV

mil^ji

- V*i-£.

I

mi ._

tx!¡,

H é

-

/(

nlW

A-

r

W T

y

i\ "*&

v

;

<H

%

A

v

v»'/«-.

2®SÍ

S* ~r 4

/'3S

. * "' v.. V it; -\V

fir'

M

k

F » .»1 r

»#î*ft >#i Li

.A* J î |f

f l'

IÍ«***''

MK

wm

^s,

"t/;

k-1 \

r

\/ L

L.-'

mw

^

«^

Centre pages

Above left: the decorative structure known as ElTransparente ("The transparent"), executed byNarciso Tomé in the ambulatory of Toledocathedral, Spain, between 1721 and 1732. Likethe Obradoiro, the façade of the cathedral ofSantiago de Compostela, it is an example of ahighly ornamental, dynamic baroque additionto a building of a different style, in this caseGothic. (See article page 14.)Photo © Mas, Barcelona

Below left: high altar and upper nave of thechurch of St. John Nepomuk (1733-1746),Munich, Fed. Rep. of Germany, by the brothersCosmos Damián Asam (1686-1739) and EgidQuirinAsam (1692-1750). (See articlepage 42.)Photo © A. Hornak, London

Centre: Triumph of St. Ignatius (1685), a ceil¬ing fresco by the Jesuit priest Andrea Pozzo(1642-1709) in the rhurch of St. Ignatius inRome. In this masterpiece of illusionism, Pozzocreates above the real structure of the church agrandiose trompe-1' architectural settingopening on to the heavens, where the founderof the Jesuit order is welcomed. (See articlepage 30.)Photo © Scala, Florence

Above right: St. Bonaventura Lying in State(1629) by Francisco de lurbarán (1598-1664).The works of this Spanish painter, who hadmany commissions from monastic orders, areimposing in their sobriety andprofoundsense ofmysticism. (See article page 14.)Photo © RMN, Paris. Louvre Museum

Below right: theatrical attitudes and gesturesinfuse a powerful sense of movement into thisAssumption (1718-1722), executed by EgidQuirin Asam for the choir of the monasterychurch of Rohr (Fed. Rep. of Germany). Thework of the Asam brothers marked a high pointin Central European baroque sculpture and de¬coration. (See article page 20.)Photo © Toni Schneiders, Lindau, Fed. Rep. of Germany

QLU

O

©

I

iI

HOL

' _ 111

The stately heritageof Portuguese Baroque

BY JOSE-AUGUSTO FRANCA

Colour page left

Above: interior ofthe church ofthe Third Orderof St. Francis, Salvador, Brazil. With its gildedsculptures and mouldings, this early 18th-cen¬tury church is typical of Brazilian and Portu¬guese architecture. (See article page 39.)Photo Moisnard © Explorer, Paris

Below left: the "Angel with the Arquebus"(Peru). This typical figure of Andean baroqueart is here shown in an anonymous 18th-century painting of the Cuzco School. (See arti¬cle page 36.)Photo © Rojas Mix, Paris. Manuel Mujica Crallo Collection

Below right: glazed andpainted tile or azulejofrom the stairway of the pilgrimage church ofNossa Senhora dos Remedios (1750-1760),

Lamego, Portugal. The azulejo is an essentialdecorative feature in Portuguese architectureand is also widely found in Spain and Brazil.Photo S. Marmounier © CEDRI, Paris

PORTUGUESE Baroque did notreally come into its own until theyoung King John V (1706-1750), his

coffers filled with the recently discoveredtreasures of Brazil, determined to make a

symbolic affirmation of his power with theambitious project of the monastery-palace-church of Mafra, on the construction of

which, from 1717, all the resources of the

kingdom were to be concentrated.J.F. Ludwig (known as Ludovice in Por¬