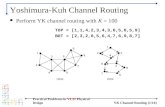

Student - Startseite · 2014-05-14 · design elements, learning communities appear to be a...

Transcript of Student - Startseite · 2014-05-14 · design elements, learning communities appear to be a...

StudentSuccess inCollegeCreating Conditions That Matter

George D. Kuh

Jillian Kinzie

John H. Schuh

Elizabeth J. Whitt

and Associates

Copyright © 2005, 2010 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-BassA Wiley Imprint989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in anyform or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise,except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, withouteither the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of theappropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers,MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests tothe publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley &Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online atwww.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for furtherinformation may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when itis read.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their bestefforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to theaccuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any impliedwarranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created orextended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies containedherein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional whereappropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any othercommercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or otherdamages.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bassdirectly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears inprint may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataStudent success in college : creating conditions that matter / George D. Kuh . . . [et al.].—1st ed.

p. cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0-7879-7914-7 (alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-470-59909-9 (paperback)1. College student orientation—United States. 2. Documenting Effective Educational Practice(Project) I. Kuh, George D. II. Documenting Effective Educational Practice (Project)LB2343.32.S79 2005378.1′98—dc22 2004027912

Printed in the United States of America

first edition

PB Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Preface ix

Part ONE: INTRODUCTION 1

1. Student Engagement: A Key to Student Success 7

Why Effective Educational Practice Matters 8

Documenting Effective Educational Practice (DEEP) 10

Keep in Mind 18

No Single Blueprint for Student Success 20

Part TWO: PROPERTIES AND CONDITIONSCOMMON TO EDUCATIONALLY EFFECTIVECOLLEGES 23

2. ‘‘Living’’ Mission and ‘‘Lived’’ EducationalPhilosophy 25

Mission 25

Operating Philosophy 27

Meet the DEEP Schools 28

iii

Making Space for Difference 59

Mission Clarity: ‘‘Tell Me Again—What Are We About?’’ 59

Summary 61

What’s Noteworthy about a Living Mission and Lived EducationalPhilosophy 62

3. An Unshakeable Focus on Student Learning 65

Valuing Undergraduates and Their Learning 66

Experimenting with Engaging Pedagogies 69

Demonstrating a Cool Passion for Talent Development 77

Making Time for Students 80

Feedback: Improving Performance, Connecting Students andFaculty 84

Summary 88

What’s Noteworthy about Focusing on Student Learning 88

4. Environments Adapted for EducationalEnrichment 91

Using the Setting for Teaching and Learning 93

Creating Human-Scale Learning Environments 106

What’s Noteworthy about Adapting Environments for EducationalAdvantage 108

5. Clear Pathways to Student Success 109

Acculturation 111

What New Students Need to Know 113

Affirming Diversity 116

Alignment 123

iv Contents

What’s Noteworthy about Creating Clear Pathways to StudentSuccess 131

6. An Improvement-Oriented Ethos 133

Realizing the Vision: The University of Texas at El Paso 134

Making Student Success a Priority: Fayetteville State University 136

Investing in Undergraduate Education: The University ofMichigan 138

Fostering Institutional Renewal: University of Maine atFarmington 140

Championing Learning Communities: Wofford College 142

Creating a Campuswide Intellectual Community: UrsinusCollege 145

Positive Restlessness 146

Curriculum Development 150

Data-Informed Decision Making 152

Summary 155

What’s Noteworthy About Innovating and Improving 156

7. Shared Responsibility for Educational Quality andStudent Success 157

Leadership 158

Faculty and Staff Diversity 163

Student Affairs: A Key Partner in Promoting Student Success 164

Fostering Student Agency 167

The Power of One 170

What’s Noteworthy about Sharing Responsibility for EducationalQuality 171

Contents v

Part THREE: EFFECTIVE PRACTICES USED AT DEEPCOLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES 173

8. Academic Challenge 177

High Expectations for Student Performance 178

Extensive Writing, Reading, and Class Preparation 182

Rigorous Culminating Experience for Seniors 188

Celebrations of Scholarship 190

Summary 191

9. Active and Collaborative Learning 193

Learning to Learn Actively 194

Learning from Peers 195

Learning in Communities 198

Serving and Learning in the Local Community 200

Responding to Diverse Learning Styles 204

Summary 206

10. Student-Faculty Interaction 207

Accessible and Responsive Faculty 208

Academic Advising 213

Undergraduate Research 214

Electronic Technologies 216

Summary 217

11. Enriching Educational Experiences 219

Infusion of Diversity Experiences 220

International and Study Abroad 226

vi Contents

Electronic Technologies 230

Civic Engagement 233

Internships and Experiential Learning 236

Cocurricular Leadership 238

Summary 239

12. Supportive Campus Environment 241

Transition Programs 242

Advising Networks 245

Peer Support 248

Multiple Safety Nets 251

Special Support Programs 252

Residential Environments 257

Summary 260

Part FOUR: SUMMARY ANDRECOMMENDATIONS 263

13. Principles for Promoting Student Success 265

Tried and True 266

Sleepers 275

Fresh Ideas 284

Perennial Challenges 287

Summary 294

14. Recommendations 295

Organizing for Student Success 297

Conclusion 316

Contents vii

Epilogue 319

Advancing the Student Success Agenda 322

Drifting Off Course 330

Sustaining Effective Educational Practice 334

Campus Culture and Sustaining High Performance 341

Final Word 342

References 345

Appendices 353

Appendix A: Research Methods 353

Appendix B: Project DEEP Research Team 363

Appendix C: National Survey of Student Engagement 373

Index 375

viii Contents

PREFACE

A LOT HAS changed in higher education in the five years sinceStudent Success in College (SSiC ) first appeared. For one thing, thecollege-going stakes are even higher today, both in terms of costsand potential benefits to students and society. To be economicallyself-sufficient in the information-driven world economy, some formof postsecondary education—preferably a baccalaureate degree—is allbut essential (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2007).As a consequence, unprecedented numbers of historically underservedstudents are coming to campuses. Thus, higher education in the UnitedStates must do something at a scale as yet not realized: provide a high-quality postsecondary education to more than three-quarters of the adultpopulation. Yet many students do not have the academic preparation nec-essary for success in college. Many students find their campus social as wellas academic environments somewhat foreign—even unfriendly—andchallenging to navigate. And many students cannot afford the cost ofattendance. By the same token, not all colleges and universities are wellpositioned to help all their students succeed and reap the full benefits ofundergraduate education. The challenge is clear: colleges and universitiesmust find ways to help more students attain their educational goals.

However, having a college degree is a hollow accomplishment if onedoes not acquire in the process the skills and competencies demanded bythe 21st century. Indeed, institutions are under continuing pressure fromstate and federal oversight agencies as well as accreditors to demonstratethat they are doing everything possible to graduate students in a timely

ix

manner and demonstrate that students are learning what colleges intend.This message was driven home by the National Commission on theFuture of Higher Education (2006), which questioned, among otherthings, what and how much students were learning. Whether one issympathetic with the tone or substance of the commission’s final report,the group’s deliberations and bully pulpit reinvigorated debate aboutwhat institutions should be doing to foster student success and howto measure and report the degree to which students were attaining thedesired outcomes of college.

The recent economic recession has made meeting these challengeseven more formidable. Public institutions—especially communitycolleges—are particularly squeezed as their enrollments balloon in theface of deep reductions in state and local funding. Even well-endowedinstitutions—Harvard is a good example—have been forced to cutstaff and programs. Although it is not clear how access will be affectedby reduced funding for higher education, one thing is plain: the timesrequire learner-centered faculty and staff familiar with conditions for thesuccess, broadly defined, of all their students (Kuh, Kinzie, Buckley,Bridges, & Hayek, 2007). How can a college or university create theseconditions? Fortunately, there are places to turn to get some good ideasfor what to do. That’s what this book does—describes policies andpractices associated with student success from an array of different typesof ‘‘high performing’’ institutions.

PURPOSE OF THE BOOKThe Documenting Effective Educational Practice (DEEP) project onwhich this book is based follows in the tradition of previous effortsto document noteworthy performance in postsecondary settings. Twoof the better-known volumes that set forth many of the key conceptsassociated with student success and strong institutional performance areInvolvement in Learning (Study Group on the Conditions of Excellencein American Higher Education, 1984) and ‘‘The Seven Principles forGood Practice in Undergraduate Education’’ (Chickering & Gamson,1987). A handful of other reports expand on these and related factors andconditions in more detail, among them Peter Ewell’s (1997) synthesis

x Preface

produced for the Education Commission of the States’ Making QualityCount. Other major studies of educational effectiveness are mentionedin Chapter One. Taken together, these reports point to the followinginstitutional conditions that are important to student development:

• A clear, focused institutional mission

• High standards for student performance

• Adequate time on task

• Balancing academic challenge with support for students

• Emphasis on early months and first year of study

• Respect for diverse talents and cultural differences

• Integration of prior learning and experience

• Ongoing practice of learned skills

• Active learning

• Assessment and feedback

• Collaboration among students

• Out-of-class contact with faculty

Many of these practices have taken root to varying degrees in collegesand universities across the country. For example, thanks to the pioneeringwork of John Gardner and his colleagues, first at the University of SouthCarolina and more recently at the Policy Center on the First Year ofCollege, many institutions have concentrated resources on first-yearstudents. Though they differ in structure, coherence, length, and otherdesign elements, learning communities appear to be a ‘‘high-impactactivity’’ (Kuh 2008)—that is, students who participate in them aremore engaged in other educationally purposeful activities and reportgaining more from college. Other high-impact activities—includingstudy abroad, student-faculty research, and service learning—also seemto benefit students as well as those with whom they interact, includinglocal agencies. The national movement to incorporate more active andcollaborative learning activities continues to gain momentum. Indeed,

Preface xi

we were surprised after the first round of National Survey of StudentEngagement (NSSE) results in 2000 by the amount of active andcollaborative learning students reported.

These effective educational practices have been around long enoughthat even casual readers of the professional higher education literatureare familiar with them. They are working their way into discipline-based journals as disparate as communication studies, economics, andengineering, as well as periodicals that focus broadly on the liberalarts and sciences, such as Liberal Education and Daedulus. Absent fromthe literature when we undertook Project DEEP were context-specificdescriptions of what these practices looked like in different settings andthe constellation of factors and conditions that supported them. In otherwords, how does an educationally effective college or university addressand meet the challenges of the 21st century? The 20 institutions featuredin this book provide some instructive answers to this question.

HOW TO READ AND USE THIS BOOKThis edition of SSiC differs from the first in two main ways. First, thisPreface has been updated. Although it expresses many of the same ideasas in the first edition, some additional information is included aboutthe impact of the Documenting Effective Educational Practice (DEEP)project, both on the participating institutions and their continuingrelevance for other colleges and universities. The second major change isthe addition of an Epilogue that describes some of what has transpiredover the past few years on these campuses as they continue to focus onstudent success.

The book is divided into four parts. Part One sets the stage, dis-cussing in more detail why we undertook the Documenting EffectiveEducational Practice (DEEP) project. As we explain in Chapter One,we set out to identify and document what strong-performing collegesand universities do to promote student success, which we defined ashigher-than-predicted graduation rates and better-than-predicted stu-dent engagement scores on the NSSE. In addition, we summarize howand why we selected this particular set of schools. We also introduce theconcept of student engagement and describe its relationship to college

xii Preface

student success. Appendix A summarizes the research approach we usedto collect information from the participating institutions.

In Part Two (Chapters Two through Seven) we discuss the sixoverarching features we found to be common to the 20 DEEP colleges anduniversities. Chapter Two is especially important, as it includes descriptiveinformation about each institution’s mission and context, which isneeded to understand and interpret how and why the specific policiesand practices illustrated later work so well to promote student success. Aswe emphasize throughout, the noteworthy level of performance achievedby these colleges and universities is a product not only of the programsand practices they have in place, but of the quality of the initiativesand the numbers of students touched by them in meaningful ways.In addition, the synergy and complementarity of these efforts createa success-oriented campus culture and learning environment. ChapterSix illustrates some of the circumstances and triggering events that putseveral DEEP schools on a path toward the institutional improvementthat created these conditions.

Chapters Eight through Twelve in Part Three present examples ofpolicies, programs, and practices that can be adapted by other institutionsto enhance student engagement in each of the five areas of effective educa-tional practice measured by the National Survey of Student Engagement.We present a mix of some of the more common examples along with asprinkling of novel programs to illustrate that institutions can reach fairlylarge numbers of students with high-quality initiatives while also tailoringefforts to address the specific needs of groups of students. We’re con-vinced that many of these practices can be adapted productively by otherinstitutions, whether or not they are similar in mission, size, and so forth.

Even with a book of this length, it’s not possible to describe everynoteworthy initiative at these 20 schools. Equally important, some pro-grams and practices have been discontinued since the first edition waspublished. For example, the University of Michigan no longer has aPOSSE program, and Sewanee disbanded its First Year Program. Someschools have expanded or added other effective programs and practices.So many changes or modifications have been made that it is not practicalto try to note them all in the text. We do so in a few instances in theEpilogue to illustrate some lessons about sustainability and how some

Preface xiii

of the schools have broadened and deepened their commitment to foster-ing student success. Moreover, even though some practices no longer arein use at a DEEP school or have morphed into something different, theymight inspire the development of equally productive initiatives elsewhere.

In Part Four, we summarize and interpret the implications of ourfindings. Chapter Thirteen synthesizes the principles that guide the workof large numbers of faculty and staff members at DEEP colleges. ChapterFourteen offers recommendations for colleges and universities that arecommitted to enhancing student success. In addition to these generalrecommendations, almost every page of Chapters Two through Twelvecontains one or more ideas for improving educational practice. Thus,the book’s utility will increase upon subsequent readings, after the readerabsorbs the big picture of what makes for effective educational practice.The foundation of strong performance is a multilayered tapestry ofenacted mission, coherent operating philosophy, and promising practiceswoven together and reinforced by key personnel in a consistent, caringway to create a compelling, coherent environment for learning. Finally,the Epilogue revisits what we are convinced are among the most importantobservations and recommendations from the study, filtered through fiveyears of reflection and additional insights gained from working with theseand other colleges and universities on the student success agenda. We alsodraw on information, gathered via conference calls with key respondentsat the institutions, about what has transpired at DEEP schools since thestudy ended. We describe how these schools have tried to respond topersistent challenges, such as aligning priorities and reward systems withinstitutional mission and values, balancing faculty and staff workload,and sustaining effective programs and practices. In some cases they havenot made a great deal of progress toward resolving these systemic issues.

Research notes and references are used sparingly in the middle sectionsof the book, as we want to focus on what these institutions do by way ofeffective educational practices. As we indicated earlier, we have benefitedfrom the groundbreaking work of those who have gone before and citerelevant work, especially early in the book and again when summarizingand synthesizing our findings in Chapters Thirteen and Fourteen.

During our almost two years in the field (2003 and 2004), we talkedwith more than 2,700 people across the 20 campuses, many of them more

xiv Preface

than once. Since that time, for various reasons, we’ve revisited more thana dozen of these schools again and have contacted all of them at one pointor another at conferences and in other ways. The more time we have spenton these campuses, talking with faculty and staff and learning more aboutwhat they do and how they do it, the more impressed we are with the rangeand quality of their initiatives. This could become mildly problematic,if the high regard we developed for the good work at these collegesand universities creates the appearance that we are proselytizing on theirbehalf. That’s not our intent, though we admire the convictions thatanimate these institutions and their willingness—even enthusiasm—forexperimenting with promising pedagogical approaches and organizationalarrangements. Another reason the text may seem overly generous is thatour prose is intentionally descriptive, not evaluative. That is, because wesought to discover and feature what is working well on these campuses,we do not dwell on their shortcomings.

No organization is perfect, including these fine colleges and univer-sities. They grapple every day with many of the same challenges facingmost institutions, and we address some of these matters in Chapters Twoand Thirteen. For better or worse, we say little about other perennialissues bedeviling these and other colleges today, such as the proper roleof athletics, helping students meet the rising cost of college, and dealingwith the perennial problem of faculty and staff overload, all of whichaffect whether some students will benefit to the fullest extent from thecollege experience. But as we explain later, one of the qualities that makethe DEEP schools distinctive is the way they address issues such as thesewhile keeping their eye on the prize of student success.

IMPACT OF THE BOOKBy March 2010, more than 18,000 copies of SSiC were sold. Requests byadministrators and faculty members at colleges and universities regardinghow to adapt the lessons from SSiC and enhance the conditions forstudent success on their campuses prompted us to produce a companionvolume to SSiC , Assessing Conditions to Enhance Educational Effective-ness: The Inventory for Student Engagement and Success (Kuh, Kinzie,Schuh, & Whitt, 2005). That volume details a self-guided framework

Preface xv

for conducting a comprehensive, systematic, institution-wide analysis,including sets of diagnostic queries that focus on the six propertiesand conditions common to high-performing schools, as well as thefive clusters of effective educational practices featured on NSSE. About3,300 copies of the Assessing Conditions workbook have been purchased.More than a few institutions bought copies of both publications forgroups such as strategic planning teams members, trustees, and facultydevelopment committees. A couple dozen other publications focusedall or in part on DEEP campuses as well as a set of sixteen prac-tice briefs (http://nsse.iub.edu/institute/index.cfm?view=deep/papers).DEEP research team members have been invited to more than 75 cam-puses to tell the DEEP story. In addition, we’ve reported the findings ofthe project or otherwise featured its implications in dozens of conferencepresentations and other venues. In graduate programs in higher educa-tion and student affairs, SSiC or selected chapters are required reading.And the volume has some international appeal, having been translatedinto Arabic! These facts were not lost on the good people at Jossey-Bass,and we gladly accepted their invitation to ‘‘freshen up’’ the volume byupdating this Preface and adding an Epilogue about what we’ve learnedsince and what the DEEP campuses are doing (or not doing) today topromote student success.

While people at DEEP campuses expended significant time andenergy talking with and otherwise assisting us during the study andsince, the schools also have derived various benefits from the project. Formost, it affirmed that they were, in the words of a Winston-Salem StateUniversity colleague, ‘‘doing something great!’’ One reason the currentpresident and provost were attracted to California State UniversityMonterey Bay was how the institution was portrayed in the book. Mostof the DEEP schools have referred to the book for various reasonsand in different venues. University of Michigan President Mary SueColeman regularly refers to the study when she speaks to prospectiveand admitted students and their families both on and off campus.The University of Texas at El Paso incorporated DEEP findings in itsstrategic plan, University of Texas System accountability reports, TexasHigher Education Coordinating Board reports, and regional and nationalconference presentations. Alverno College used the conditions for student

xvi Preface

success to organize their evidence for educational effectiveness reportedin their reaccreditation self-study for the Higher Learning Commission.Ursinus College featured passages from SSiC in its Middle States self-study, and the Middle States visitation team also cited the book in itsreport following the visit!

The descriptions of various educationally purposeful policies andpractices inspired faculty and staff members at Wofford College andFayetteville State University to redouble their commitment to effectiveeducational practice and innovation. Being included in Project DEEPput leaders from the University of Maine at Farmington in touch withcounterparts at other DEEP institutions and energized them to advocatefor institutional change, including deemphasizing institutional rankingsand focusing more on experiences that would enhance student learning.At Macalester College, benefits were both internal and external to thecollege. Not only did the study stimulate internal discussions and ideasfor change, the college drew on descriptions of its practices in the bookwhen providing information to candidates for student affairs positions,helping them understand its student affairs philosophy. Evergreen StateCollege found some practices at other schools worth emulating, such asadopting a common reading—a touchstone text—similar to what Wof-ford and some other institutions were doing. Participating in the projectlegitimized in the eyes of Longwood University faculty and staff the insti-tution’s distinctive mission of promoting citizen leadership and helpedthem understand the impact of curricular and cocurricular programs onstudents. As a result, Longwood reports increased collaboration betweenacademic and student affairs. Sweet Briar College faculty, staff, students,and alumni returned again and again to its DEEP report during its strate-gic planning process. According to former Sweet Briar president, ElisabethMuhlenfeld, this helped the college to be ‘‘more focused on meaningfulstudent engagement than before.’’ At Miami University, the findings werediscussed at the president’s executive committee meetings and prompted,among other things, reform of the advising system. The new vice presi-dent for student affairs at Wheaton College discussed the book and hercampus report with her staff to better understand the campus culture.

We are pleased but not surprised that SSiC encouraged these insti-tutions to deepen their commitment to critical reflection. Such a

Preface xvii

response is consistent with the ethic of positive restlessness that generallycharacterizes them. More important is what the findings from the DEEPproject prompted other institutions to do. Thanks to the willingness ofthe 20 DEEP schools to open their campuses to inspection, many morecollege and university administrators, faculty, scholars, and educationalpolicymakers have instructive images of effective educational practice forthe 21st century that provided inspiration and helped them focus onthe ‘‘right things.’’ This is what we hoped would happen. The extentto which this book succeeded in that regard and continues to animatediscussions about student success and guide campus efforts toward thatend benefits both institutions and their students. What could be better?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSA project such as this has many intellectual debts, not the least of whichis to the inspirational students, faculty, and staff at the institutions wevisited. As will become clear early on, DEEP colleges are special placesprecisely because of the people who work, live, and study there. Staff at thenow-defunct American Association for Higher Education (AAHE) werevery helpful, especially Barbara Cambridge, Clara Lovett, and Lacey Leeg-water. We are also indebted to Sam Cargile and Susan Conner at LuminaFoundation for Education for their keen interest and unwavering supportfor a study of high-performing colleges. Sam is still at Lumina while Susanis pursuing other interests. Another key partner was Wabash Collegeand what was then its new Center of Inquiry in the Liberal Arts (CILA).Offering sage advice behind the scenes from beginning to end werepast and present members of the NSSE National Advisory Board (http://www.iub.edu/∼nsse/html/advisory board.htm) and DEEP AdvisoryPanel (http://education.indiana.edu/∼nsse/nsse institute/deep project/student success/advisory board.htm).

A special word of gratitude is due to several proponents of studentengagement who continue to influence our thinking and work. C. RobertPace, UCLA professor emeritus, introduced the concept of quality ofeffort in the early 1970s, and with Spencer Foundation support launchedthe College Student Experiences Questionnaire (CSEQ) research pro-gram. Many of the questions on the NSSE survey are from the CSEQ.

xviii Preface

Alexander Astin’s landmark studies across several decades demonstratedthe importance of involvement, in effect making it a key construct inresearch on college students. To us, Peter Ewell is the godfather of NSSE,as he chaired the design team that developed the survey and remains atrusted advisor. Russ Edgerton had the foresight and courage to investin the premise and promise of student engagement when he directedthe education program at the Pew Charitable Trusts. Without Russ’sleadership and Pew’s support, we’d be nowhere near this far along ininfluencing the nature of the public dialogue about what matters tocollegiate quality.

In every possible way, we were buoyed by our colleagues and friends atthe Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. They coveredfor us during our many trips to DEEP schools, for which we are mostgrateful. To a person, they are a superbly talented and productive group.Our work and lives are enriched immeasurably by being around them.

Last but certainly not least, the rich and varied expertise of the DEEPresearch team (Appendix B) made this project a career highlight. Repre-sented as ‘‘Associates’’ in the list of authors, they are co-investigators andkey contributors to this volume in every sense of the word. Their insightsand excellent field work appear on every page. Equally important, col-lectively they brought a breadth and depth of perspective and experiencethat may be heretofore unmatched in studies of colleges and universities.We are deeply appreciative of what they brought and gave to this projectand book. Thanks, DEEP team!

January 30, 2010 George D. KuhBloomington, Indiana

Jillian KinzieBloomington, Indiana

John H. SchuhAmes, Iowa

Elizabeth J. WhittIowa City, Iowa

Preface xix

Student Successin College

Part I

Introduction

On other campuses, I hear they just read from the book and discuss thematerial in the abstract. Here we tell how the reading relates to our life—ourhistory and background. It is much more personal and has feeling. I wouldnot be able to relate otherwise; that is what made the education engagingfor me.

—California State University at Monterey Bay first-year student

The one thing that really helped me to get through college was the faculty.They have this philosophy that the first thing that comes to mind is thestudent. They have an open door and open ears to what students want to doin college and what they want to learn.

—University of Texas at El Paso senior

I never thought I would study abroad because I am such a homebody . . . .I heard about the London Review in a presentation in one of my businessclasses and I thought I should look into it. I went on the two-week trip andthen decided to spend an entire semester abroad.

—University of Kansas senior

Wabash has made me a man. Instantly there’s a lot going on and you’reexpected to jump in headfirst. It breeds confidence. You think, ‘‘Hey, I cando this, too.’’ You get the sense that you can achieve anything.

—Wabash College junior

The people here have helped me develop who I am. No one ever encouragedme in science before. Internships and study abroad got me into environmentalactivism. I’ve learned how the majority of the world lives, and that you don’tneed all the stuff you think you need. There are so many opportunities hereand once I started, I just never quit!

—Wheaton College senior

The whole education at UMF is about constant reflection. You develop adeliberate, thinking state of mind. Thinking critically becomes second nature.They’re tricky like that!

—University of Maine at Farmington senior

The number one thing I like here is the interaction in the classroom. We haveintimacy and respect with the faculty. They don’t baby-sit you, but you get alot of attention. You’re asked to reflect on yourself and your character, and itbroadens your understanding of life. I’m a better leader because of it.

—Longwood University junior

Students are so empowered here to be engaged. We truly have ownership ofour lives and so we just assume we’ll be in charge of things. It’s amazing howmotivated that makes you to take on responsibility and succeed.

—Miami University sophomore

There are many challenges here. You have to challenge yourself academically,challenge yourself to understand people from diverse backgrounds, andchallenge yourself to understand the community and the world.

—Macalester College junior

2 Student Success in College

These students seem to be thriving in college. They describe experi-ences that challenged them to develop skills, awareness, and confidence.Although the colleges the students attend are very different, the institu-tions perform well on two important measures. When the institutions’resources and student characteristics are taken into consideration, allgraduate more students than might be predicted, and their students par-take more frequently than predicted in activities that encourage learningand development.

What accounts for these achievements? And what can other collegesand universities learn from them to enhance their own effectiveness?

The Educationally Effective Colleges Quiz includes some clues. (Hint:Review the student quotes earlier.) The answers are at the end of ChapterTwo. If you read straight through to that point, without skipping thepages in between, you should do well on the quiz. What will becomeapparent early on is that the colleges and universities represented inthe questions are very different in size and educational mission. Someon the list might surprise you. What they all have in common is thatthey take undergraduate education very seriously and have implementedpolicies and practices and cultivated campus cultures that encourage theirstudents to take advantage of a variety of educational opportunities.

To find out more about these institutions and what they do topromote student success, read on!

Part I: Introduction 3

Exhibit 1. Educationally Effective Colleges Quiz.

1. What college uses peer evaluations, external assessors from the localcommunity, and student self-evaluations to assess student learning?

2. What university located on a former military base requires all studentsto complete two service learning courses?

3. At what institution do groups of students and faculty membersdecide together what to study for an extended period of time usingan interdisciplinary approach?

4. What public Historically Black College or University (HBCU)increased its first-to-second-year retention in five years by institutinga wave of student success initiatives?

5. What mid-Atlantic public university where more than 40% of theundergraduates are students of color or international studentssystemically incorporated electronic technology when redesigning100+ courses?

6. At what Jesuit university do students annually coordinate and per-form about 30,000 hours of community service?

7. What medium-sized university revised and connected its generaleducation program more tightly to students’ out-of-class experiencesto pursue its mission of Preparing Citizen Leaders?

8. What liberal arts college emphasizes internationalism and multicul-turalism in its mission and has more than half of its students studyabroad?

9. At what public university do all 15,000 undergraduates have acapstone experience that requires them to integrate liberal learningwith specialized knowledge?

10. At what women’s college do students take at least three writingintensive courses and begin each academic year by marching to thetop of a nearby hill to the founder’s grave site for a remembranceceremony?

11. What public research university annually bestows on 20 facultymembers at the beginning of each academic year prestigious$5,000 awards to honor outstanding teaching?

12. What small public university improved its persistence rates by creat-ing campus jobs for more than half of its students?

4 Student Success in College

Exhibit 1. (Continued)

13. What major public research university ranks in the top 10 amongits peers in terms of external grants and contracts but also did sixmajor studies of the quality of the undergraduate experience of itsstudents since 1986?

14. At what 10,000-acre liberal arts college campus do faculty membersand many students still wear academic robes to class?

15. What Hispanic-serving university is one of the six Model Institutionsfor Excellence (MIE) identified by the National Science Foundation?

16. At what liberal arts college does the academic dean host a biweeklycolloquium to introduce new faculty members to key issues at thecollege by talking with senior colleagues?

17. At what liberal arts college is the entire student code of conductonly 24 words long?

18. What former women’s college became ‘‘consciously coeducational’’in the late 1980s and offers a ‘‘gender-balanced’’ curriculum?

19. What university designates sections of the freshman seminar for stu-dents interested in specific majors and expects the faculty memberteaching the course to serve as a mentor and academic advisor tothe students in their section?

20. What is the smallest college playing Division I football where theinterdisciplinary learning communities for first-year students aredesigned and led by faculty and student preceptors?

The DEEP SchoolsAlverno College Sweet Briar CollegeCalifornia State University at University of Kansas

Monterey Bay University of Maine at FarmingtonEvergreen State College University of MichiganFayetteville State University University of Texas at EI PasoGeorge Mason University Ursinus CollegeGonzaga University Wabash CollegeLongwood University Wheaton College (Massachusetts)Macalester College Winston-Salem State UniversityMiami University Wofford CollegeSewanee, University of the South

Part I: Introduction 5