Southeast Asian Religions: A Perspective on. Historical ...The Beginning of Buddhism In the general...

Transcript of Southeast Asian Religions: A Perspective on. Historical ...The Beginning of Buddhism In the general...

EAJT/4:2I86

Southeast Asian Religions: A Perspective on. Historical Buddhism within

the Developing States of Southeast Asia

Paul Rutledge*

The study and examination of religion or relgions requires a multiplicity of tools. Since man's religions invariably reflect human experience and understanding, the study of religion encompasses history, ethnology, linguistics, literature, philosophy, economics, sociology, political science, and anthropology.

Among the "Great Religions" of the world may be discovered repetition and similarity, as well as, variations and significant differences. This similarity becomes clear when it is understood that of the five great religions-Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism-a reduction to two may be made historically. Hinduism and Judaism may be considered the genesis of the other three: Hinduism as the seed ground for Buddhism; Judaism, for Christianity and Islam.

The differences between the two major traditions may be viewed from a philosophical perspective as a springboard to theological developments. For instance, there is a fundamental difference in the way time is perceived. The Western orientation of linear time is countered by the Eastern orientation of cyclical time. In addition there is a vast gulf between the East and West in the perception of life. For the Western mind, generally speaking, life is good. To extend life is a positive course and a course to be desired leading to the conceptualization of an after life. To the Eastern mind, generally speaking, life is bad and the naturitl course is for one to seek escape from life. Subsequently, there is no highly developed eschatology for Eastern religions. Instead, one is offered an escape from perpetual or eternal existence, and Nirvana becomes a mystical union with the universe, not an extension of life.

The Beginning of Buddhism

In the general development of Buddhism one can clearly see the effects of the Eastern mind. Founded by Siddhartha Gautama (560-480 B. C.), a prince of the Kahatriya caste of Hinduism, Buddhism reflects the conceptualization of life as a burden to be discarded or overcome.

At twenty-nine years of age, Gautama identified the burden of life in the twofold problem of sin and suffering. Seeking an answer to this dilemma he attempted philosophical speculation without successfully reaching a conclusion. He, therefore, decided to undertake the path of bodily asceticism (Gaer, 1967:167). After five years of searching he decided to decrease the intensity of this asceticism and still contiriue along this general path. At thirty-five, while seated under the bo tree (bodhi) in meditation, he experienced enlightenment and became the Buddha, the enlightened one (Latorette, 1956:91). During the remainder of his life he taught and discipled others on the Middle Path to Enlightenment. This

*Paul Rutledge is Chairperson of Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work, Oklahama Baptist University, Shawnee, Oklahama, USA

138

EAJT / 4:2186

enlightenment would lead to Nirvana, the place of freedom from rebirth. Siddhartha Gautama died at the age of eighty.

Following his death, the Buddha's disciples organized into a sangha (religious order) with definite rules and schedules. These rules necessitated a yellow robe, a shaven head, daily meditations, · and affirmation of the Three Refuges. It was agreed that Refuges was to be found in the Buddha, the dharma (law/doctrine), and in the sangha. In addition, ten negative precepts had to be followed. These precepts taught abstinence from destroying life, stealing, lying, committing adultery, drinking intoxicants, eating at forbidden times, dancing and attending theatricals, adorning oneself, having large beds, and possessing gold or silver (Parrinder, 1964:144). .

Essential Features of Buddhism

One of the primary features of the Middle Path to salvation from rebirth involves true knowledge of the Four Noble Truths. These truths: (1) existence (life) is suffering, (2) .suffering is caused by inherently insatiable desires; (3) desire must be suppressed in order to end suffering and existence, (4) the way to achieve this is to follow the Eightfold Path (Ashby, 1955:37ff). The Eightfold Path entails right views, right aims or intentions, right speech, right action, right livelihood, selfdiscipline, self-mastery, and contemplation. These eight mandates form the core of the Buddha's teachings, and may be found in his early sermons, as well as in the Tripitaka. The Tripitaka ("Three Baskets") is the basic scripture for Buddhists transmitted orally from the Buddha's time in the Pali language. The Three Baskets are the Vinaya, containing monastic rules; the Sutra, teachings of the Buddha; and Adhidharma, metaphysical commentaries on the Sutra (Gard, 1961:127ff).

The Two Main Schools of Buddhism

The two main schools of Buddhism are the Hinayana (Theravada) and Mahayana schools. The Hinayana or "lesser vehicle" (tradition) is the older of the two schools and closer to the teachings of the Buddha. The Mahayana or "greater vehicle" (tradition) is the newer of the two schools and is distinguished by its adaptability and departure from the original tenets.

There are other distinctions worth noting. For instance, the Hinayana or Theravada school is to be found predominantly in Southeast Asia: Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and to some small degree in Vietnam; hence, the name, the Southern school. The Mahayana school is denoted the Northern school as it is predominant in Japan, Korea, China, Nepal, Tibet, and Vietnam (Starkes, 1978:48).

Their separation, however, is not solely geographical. The Theravada Buddhists adhere to the teachings prescribed by the original Buddha and his immediate followers. In Theravada Buddhism, the historical Buddha is the only Buddha. Mahayanists recognize the historical Buddha as only one Buddha in a long chain of Buddha manifestations. The various Buddhas, according to Mahayanists, have had different teachings and the whole of th~se teachings are accepted as scripture. This leads to a variety of Mahayana "denominations" depending on the particular scriptural teachings which are emphasized (Swearer, 1970:196).

139

EAJT / 4:2/86

Other distinction include:

THERAVADA 1. A reverent attitude toward relics

and images of the Buddha.

2. Monasteries are frequented by monks and laypeople who periodically enter to live.

3. Includes many lesser deities depending on the country in which it resides.

4. The worship of the Buddha is merely an act of commemoration.

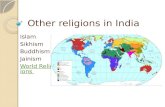

1 MONGOLIA 2 CHINA

9 BURMA 10 LAOS

MAHAYANA 1. Buddha is considered the supreme

Reality, or an incarnate savior (emphasis found in late Sanskrit scriptures). Buddha is the essence of existence

2. There are innumerable bodhisattvas; men who have attained nirvana but postpone entrance in order to aid others.

3. Heaven and hell are often vividly portrayed.

4. The Buddha himself is a personification of the law.

(Radhakrishnan, 1957:272fO

17 PHILIPPINES 18 FORMOSA

3 TIBET 11 THAILAND 19 KOREA 4 NEPAL '

5 BHUTAN 6 INDIA

12 CAMBODIA (KAMPUCHEA) 13 VIETNAM 14 MALAYSIA

20 JAPAN 21 SOVIET UNION

7 AFGHANISTAN 8 PAKISTAN

15 INDONESIA 16 NEW GUINEA

Genesis of Ancient Buddhism Stronghold of Theravada, Buddhism Stronghold of Mahayana' Buddhism

140

Area of Animistic Prominence Stronghold of Islamic Influcence Stronghold of Christian Influence Hinduism -

EAJT / 4:2186

The Diffusion of Theravada Buddhism into Southeast" Asia

Buddhism is the oldest of the world's three missionary religions and as such has had an extensive influence on Asia and much of Africa. The spread of Buddhism initially began from India and Sri Lanka with a break from the Hindu teaching of class and duty. The message of Buddhism was not restricted to caste or class and did not limit its community according to status or rank (Parrinder, 1964:84).

The earliest history of Buddhism's diffusion is obscured by conflicting legends and "histories". It is commonly believed that the first council was convened shortly aftet the historical Buddha's death. Following the first council by approximately one hundred years was the Council of Vesali, with the third council appearing during the reign of Emperor Asoka (r. 269-232 B. C.). By this point in history, the Theravada school was well developed and its missionary endeavors well defined (Sangharakshita:1980).

BUDDHISM (INITIAL AND GENERAL DEVEWPMENT)

/ ~ HINAYANA

/ ~ THERAVADA Sautrantika

Sarrastivda

Jodo -

(Chinese: Ching-tu)

/

MAHAYANA

1 __ - Madhyamika

~ Yogacara

(Idealism)

Zen (Syncretistic)

(Chinese and Vietnamese Ch'an)

Pure Land School "gradual enlightenment' ,

141

"sudden illumination"

EAJT 14:2186

The Second Council and Schism

The second great Buddhist council took place approximately one hundred to one hundred ten years following the Buddha's death. It is difficult to accurately access the Buddhist community at this point, but it is clear that by this council the two major schools of Buddhism were conceptually formed, if not already. separately organized.

In the one hundred years since the Buddha, Buddhism had gradually gained leverage among the "common" people in India. Concurrent with increase was a notable visibility of Buddhist influence on rulers and nobles of the cities (Ikeda, 1977:28). As the movement grew, inevitable differences in the interpretation of the principal doctrines became apparent. As a result of these conflicting interpretations the second council was convened.

The council, however, discovered a wide variance of interpretation. The monks of Vaishali, for example, wanted to reform the ten precepts including the forbidding of acceptance of silver and gold by monks. So radical were the proposals of the Vajji group that conservative monks overwhelmingly voted against the "new" religion. As a further measure, a call was issued for monks to "rigidly observe" (ibid, 1977:19ff) the rules of discipline, and freedom of interpretation was strongly discouraged. Adherence to the original doctrines was considered mandatory (Sangharakshita:1980).

There was, however, difficulty in enforcing strict discipline among the orders. The various orders throughout India functioned autonomously, and there was no one central authority. It appears that Gautama did not envision the development of a large religious organization, and therefore, the Sutra did not contain specific directions for the orders on unification. In addition, conflict had arisen between the more monastic elements of Buddhism versus the "anti-isolationalists" factions (Vaishali).

Due to these disciplinary differences, the Vaishali monks convened a conference of their own referred to as the "Great Group Recitation" (Swearer, 1955:8ff). The gathering included a group of ten thousand who opted to separate themselves from the membership of . the second council. Initially they were designated Mahasanghika or "Members of the Great Order". Over time they became known as Mahayanists thereby distinguishing themselves from the Theravadists or "Teaching of the Elders" group. Following these two primary orders, eighteen supplementary interpretations would give rise to various Buddhist schools over the next one hundred years.

King Asoka 274-236 B. C.

The prime mover for Buddhism's first massive missionary endeavor was King Asoka, an Indian monarch of the Maurya dynasty who ruled from 274-236 B. C. A convert to Buddhism, Asoka radically changed both his kingdom and his personal life style following its conversion.

Prior to his acceptance of Buddhism, King Asoka ruled in tyrannical fashion. Legend states that he assassinated his brothers in order to secure the throne, and promoted "excessive feasting and drinking" throughout his kingdom (Ling, 1972:30-31). In 266 B. C. he commissioned an expedition to conquer Kalinga, a small independent enclave on the eastern coast of India. During, and following, the battle Asoka's army slaughtered more than one hundred thousand people,

142

EAJT / 4:2/86

and Indian legends from this period speak at length about the battle (Ch'en, 1968:108ff).

As a result of this expedition, King Asoka was overcome with grief. In his regret, he turned to Buddhism and pledged to devote the remainder of his life to the propagation of the Buddha's teaching. Paramount among these teachings is reverence for life, and Asoka devoted himself to peace and the abolition of warfare (ibid, 1968:113).

Drastic changes were placed in motion upon Asoka's conversion. Reinterpreting his purpose in life, Asoka declared that his new mission was to bring happiness to his subjects. To implement this pledge, he provided medical care for all living beings, issued prohibitions on the slaughter of animals for food, provided well and water services for travellers along primary road ways, and substituted meditation for public feasting and drinking. These provisions were administered by Asoka's staff of Chief Commissioners who also were responsible for promoting Buddhist beliefs throughout the kingdom (Latourette, 1956:38ff).

Important as King Asoka's social and moral programs may have been, his role in extending Buddhism's influence is his most significant contribution. Asoka dispatched missionaries throughout his own kingdom and other parts of India, as well as to Syria, Cyrene, and Egypt (Ch'en 1968:116). Most significantly, he commissioned the evangelization of the regions adjacent to India. It was during Asoka' reign that Buddhism was carried into northwestern India,south India, and Ceylon. From northwest India the religion diffused through central Asia, and from Ceylon it diffused into Southeast Asia. .

Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced to Ceylon by King Asoka's son Mahinda, and his daughter, Sanghamitta. Travelling as a part of a trade envoy, Mahinda · and Sanghamitta were successful in converting King Tiss, and a large portion of his court. Following the King's conversion in the third century B. c., Buddhism flourished in Ceylon until the fifth century A. D. During this period extravagant temples were erected and elaborate festivals were conducted nationwide. The Chinese traveller, Fa-hsien, who visited Ceylon in the fifth century wrote of sixty thousand monks in hundreds of monasteries all of whom were provided for by the King who always prepared a food supply sufficient to feed five thousand monks simultaneously (Lester, 1973:23ff). Early in this period (first century A. D.) the canon of Theravada Buddhism was written in Pali, and the most famous commentaries on the canon were written in Ceylon. Most probably . the author of these commentaries is Buddhaghasa, a monk who lived in the early sixth century (Swearer, 1955:16).

From the sixth to the eleventh centuries, Buddhism suffered a decline in Ceylon. The invasions of the Muslim Tamils in south India had completely destroyed Buddhism in that region and threatened to reach into Ceylon. However, a renaissance developed between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries during which Ceylon retrenched followed by another period of decline between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. This decline was precipitated by Tamil invasions followed by the intervention of European powers in Ceylonese life. From 1540 to 1660 the Portugese attempted to convert the Ceylonese to Catholicism. Their efforts included the destruction of monasteries and temples, as well as, the pillage of temples and the confiscation of sacred artifacts (Landon, 1949:81). The Dutch (1658-1795) and the British (1795-1956) avoided the blatant ransacking of temples, but did-

143

EAJT/4:2/86

through policies of indifference to Buddhists and . favoritism to Christians~ manage to further deteriorate the strength of Buddhist Ceylon (Cody, 1964:217-218).

The latter part of the nineteenth century, however, proved to be the watershed for Buddhism's "return." The Buddhist monks set in motion a counteroffensive against the Christian missionaries through a series of debates and public meetings. So rejuvenated was the spirit of Buddhists by these public exchanges that orders began to experience phenomenal membership growth. The increased strehgth of the religion, coupled with a new sense of national pride, combined to undergird a growing nationalistic movement resulting in independence in 1956.

Significantly, . Ceylon had· proved . to be: (1) the stronghold of Buddhist missionary activity following the Tarnil invasion in south India; (2) the dominant Buddhist influence on Southeast Asia; (3) and a powerful element in Ceylon's spirit of nationalism. Today, Buddhism is the dominant force in Ceylon's religious, cultural, and political traditions (Cady, 1974: tester, 1973).

Burma

Tradition varies as to the origin of Buddhism in Burma. Originally conceived in legend as a convert land of Asoka's zeal, it is not until the fifth century A. D. that a flourishing Theravadacommunity can be documented. Prior to the eleventh century, Buddhists were divided between Mahayana and Tantric Buddhism in Upper Burma, and Theravada Buddhism in lower Burma. The Tantric forms of Buddhism did not follow the original teachings, but instead added the practice of magic, The followers of Tantric Buddhism were called Aris and believed one could escape the effects of karma by reciting magic formulae. They further defiled the Buddha's teachings by sending virgins to priests before marriage and by creating numerous deities depicted irisexual consort with their followers (Ray, 1946:12ff; Sangharakshita, 1980).

Theravada became dominant over the Tantric form when Anawrahta, a ruler of nothern Burma, was converted to Theravada by Shin Arahan, a Theravada monk (Ch'en, 1968:125). Following his conversion, Anawrahta invaded the South in order to secure copies of the Buddhist scriptures. Once having united the country geographically, he united it also under . the TlIeravada school. Anawrahta then closely bonded the state and religion together. The extensive ruins of Buddhist temples from Pagan provide massive and luxurious evidence of this bond (Cady, 1964:284ff).

During the British dominance of Burma, Buddhismreinairied strong inspite of the British attempt to disestablish it.· Christian schools and churches were opened and Buddhism officially removed as the state religion. Resurgence, however, came in the early twentieth century with the growth of nationalism. Although Buddhism was not reinstated as the state religion following independence, most Burmese today practice Theravada BuddhisfI1(Nash, 1971).

Historically, then Buddhism functioned in Burma to: (1) provide a common ground for the merging Of different ethnic groups into one nation and (2) serve as one of the cohesive factors for the drive to nationalism while under British rule.

Thailand

Theravada Buddhism in Thailand, unlike the Burmese experience, was never . interrupted by coloniaUnfluence. As early as the early centuries A. D., Buddhist

144

EAJT / 4:2/86

influence from lower Burma had permeated Thailand. In the eleventhcentllry, King Awawrahta invaded and conquered the northern region of Thailand and brought the religion with him. By the time the Thais from southern China migrated into Thailand, the belief in Theravada Buddhism was firmly established and readily accepted by .the new arrivals (Swearer, 1970).

As early as 1238, with the establishment of the Thai kingdom, Buddhism was considered the state religion. As such it has flourished, and since the unification of modern Thailand in the late eighteenth century (Burmese control over the northern portions was relinguished) Thailand has seen the Thai monastic order unified under one leader (Blanchard, 1958). This unification, secured in the early nineteenth century, continues as a uniqueness of Thai Buddhism. Although there are two Theravada sects, their differences are relatively minor, and monastic education is essentially the same throughout the country.

There has always been, and continues to be today, a very close tie between the Buddhist leadership and the political leaders (monarchy). Presently, Theravada Buddhism remains the state religion. The king is required by law to be a Buddhist, and as the monarch is considered the highest authority in the sangha (order). Historically, it has been customary for the king during his youth to spend several years in a monastery which further identifies his leadership with the Theravada beliefs.

Traditionally, Buddhisrn has been the foundation for the Thai kingdom and the Thai nation. Politically, culturally, and idealistically it has permeated every institution of the Thai people. It is not an elaboration to understand Buddhism as virtually synonymous with · the nation of Thailand.

Kampuchea (Cambodia)

Cambodia became a Theravada Buddhist nation in the · fourteenth century. Prior to this, the major religious influences had been Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism (Steinberg, 1959). Many of the monuments and temples inAngkor Wat, dating 800 to 1400 AD, were dedicated to Hindu and Mahayana deities.

However, . in the fourteenth century .. a change took place. The Thais .. began to send missionaries into Cambodia as early as the late thirteenth century, . and conquering armies soon followed. After the Thai capture of Angkor Wat, the Cambodians abandoned it, and even when the Thais later retreated the Cambodians left the City desolate. By this time, many Cambodians had be.en converted to the Theravada school by the Thai missionaries and occupation . forces (ibid, ·1959).

In botp. past and recent history, Cambodia has remained Buddhist. In 1972, the nation listed 99OJoof their populace as Theravada Buddhist (Swearer, 1977). Since the invasion and subsequent occupation of Kampuchea in the late 1970's by the Vietnamese, it is difficult to assess the present situation. However, it may be assumed that Buddhist .beliefs strongly persist even if operational activities of the monasteries and Buddhist schools have been discontinued.

Vietnam

Geographically, Vietnam is in southeast Asia, but religiously, it has been more closely linked with China in East Asia. Accordingly, the Buddhist influence has been. Mahayana as opposed to · Theravada .. Prior to the communist unification of the northern and southern regions of Vietnam in 1975, the Pure Land School was beginning to influence the Vietnamese Buddhists. At that time, up to seventy percent 'of the Vietnamese population was considered Buddhist.

145

EAJT 14:2/86

Summary

The missionization of Southeast Asia by Theravada Buddhism was a result of the conversion of an Indian King. Following Asoka's lead, many people accepted the Theravada beliefs through the persuasion of his monks or through the insistence of his position as King. In most countries-Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia-the existence and diffusion of the religion depended on political (royal) support. As Buddhism was greeted openly by the ruling classes, the masses of people soon converted. In addition, as a result of royal support, the teachings of Theravada Buddhism became a strong social force as well.

Theravada's Permeation of Southeast Asia

To fully understand the impact of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, one has to examine the socio-cuItural and political systems of the various countries. Although time and space do not allow a full examination, examples of various types will be used to show the depth of penetration into the region by the Theravada school.

The Politico-Religious Influence of TheravadaBuddhism

Religion plays a primary role in the development of nations in Southeast Asia. As the various autonomous states strive to create modern nations they also seek to maintain their rich heritage. Both the platform for the future and the symbolism from the past are intricately interwoven with Buddhism (Ferguson, 1975:645ff).

The predominance of religion in revitalization or nationalistic movements is not a new phenomenon. In 1699, a Lao named Bun Kwang consorted to gain political power and restore his traditional culture through the use of his Buddhist "magic powers" (Ishii, 1975:121). The concept. of phu mi bun (merit man), as claimed by Bun Kwang, is basically a Buddhist tenet. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, merit men have appeared in the Korat Plateau among the Thai-Lao peasants claiming a mira.culous path to a utopian society via Buddhist allegiance (ibid, 1975:124ff).

One historical instance of response to colonialism, in addition to several noted in the historical overview, involves a Buddhist priest who stirred the populace to patriotism via religion. Saya San, a Burmese monk in 1930 organized his followers in opposition to the British rule. Believing that magical powers would give -hiin victory over the English, Saya San declared himself the new monarch. Convinced that the British would be destroyed when he struck a particular magical gong, Saya San encouraged the people to refuse to pay the British tax on rice and other crops while looking to him for protection. When the British arrived to take Saya San into custody, the gong proved to be without effect. Saya San subsequently was arrested, tried, and executed. The intimacy, however, between the religion and the people's sense of nationalism was only heightened by this incident (Cady, 1964:512).

Following the 1940's renewed nationalism fueled by Buddhist leadership grew in Burma. As nationalism grew, Buddhism grew and the relationship was clearly "both-and," not "either-or." In the mid-1950's Theravada monks gathered to reissue an authorized version of the Tripitaka. Concurrently, the national unity of the people was more cohesive than ever. Both the state and the religion proved necessary to the other and the resurgent strength of both was dependent on their interrelationship (Spencer, 1971:109). Clearly evident is the thesis expounded by

146

EAJT/4:2I86

Clifford Geertz in Islam Observed: "a religious system is not a thing in itself, but a facet of the total culture in which it occurs; it permeates other institutions and is in turn permeated by them" (Geertz, 1968:24).

The Primacy of Buddhism

The primacy of Buddhism is also perceived in the belief systems which have incorporated an aspect of Buddhism into their own particular practice. In the Burmese situation, animism syncretistically included aspects of Buddhism until the Buddhist doctrine ultimately became predominant (Spiro, 1967:3-5). Even though Buddhism retained elements of the nats ("supernatural" spirits), it clearly became the greatest influence on both the Burmese culture as a whole and the personal value system of the typical Burmese (ibid, 1967:242). In every case, the religious beliefs directly affect the peoples' behavior and hence, their culture.

In Laos, the cult of the phi includes . Buddhism, animism, and Confucianism. The phi-spirits of the material and non-material world with power over the destiny of human beings-affects and interacts malevolently with the Buddhist Khouan (resident spirit) which must be protected from the phi. In order to protect the khouan, the eightfold path must be followed, and once again the primacy of Buddhism is revealed (Lebar, 1960:46-48; Brohm, 1963:27). Furthermore recent Laotian history also validates the "purer" Theravada Buddhism as the primacy order of religion. The two Buddhist orders, the Mahanikay and the Thammayut, comprise a well defined hierarchy and a potent political force.

The fact that Buddhism lends itself to syncretism is also seen in the Vietnamese Cao-Dai and Hoa-Hao belief systems. Although the influence is primarily Mahayanist, the ability to combine Buddhist, Thoist; Roman Catholic, and various political "theologies" and/or "ideologies" highlights Buddhism's adaptability (Fall, 1955:237; Oliver, 1976:23ff).

Modern Buddhist Missionary Efforts

Another aspect of the strength of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia is its desire and ability to send out missionaries. Since the 1920's, Buddhists have sent missionaries to the hill tribes along the Burmese borders and to tribesmen in the Laotian highlands (V os, 1959:177). As recent as 1976, Theravadist monks have been sent to the United States in order to both serve existing Buddhist communities and also to evangelize the general populace (Schecter, 1967:93; Swearer, 1977).

In Southeast Asia the organization of the Burma Buddhist World Mission has resulted In the production of numerous books and articles. Freely distributed throughout Southeast Asia and Western nations, these books and pamphlets seek converts to the Theravada position. Currently, distribution centers are being established in India for the missionization of Buddhism's birthplace.

Buddhism and Communism

According to the Marxist theory of economic determinism, aspects of human society such as laws, ethics, arts, education, and social stratification are determined by methods of production. Marxist communism Wlderstands human history to be a class struggle between the elite (wealthy) class and the laboring class. In a capitalistic economy, the worker creates the wealth through his labor but is then exploited by the capitalist who exploits the worker's production by manipulating

147

EAJT / 4:2186

the profits away from the worker (Ling, 1979). To rectify this problem, the socialist society would eliminate the private ownership of production means.

The Buddhist, however, contends that inequalities are basic to human societies. Fundamentally, Buddhism explains aspects of the human personality unexplained by communism (i. e., how can siblings differ dramatically in personality). To the Buddhist, human nature and human situations are not controlled by external circumstances but by the manisfestations of one's karma. Individuals have free will and the power to exercise that will (ibid, 1979; Takakusu, 1959).

Between these two systems, common ground is difficult to locate. Communism seeks to suppress the individual to the needs of the state; Buddhism sees individuals as individuals, free to follow personal choice. Communism adheres to the idea of materialism. It assumes that sufficient material reward brings happiness. Buddhism sees only futilism in trying to satisfy the cravings of man materialistically. In addition, man's cravings are viewed as the origin of his suffering. Communism stresses the fulfillment of material desires; Buddhism the abandonment of material attachments.

The struggle between the classes also presents conflicting views. Communism insists on the struggle between the landed and the landless (the bourgeois and the proletariat). Buddhism seeks universal brotherhood, and the harmony of mind and matter. Communism opposes religion as the instrument of bourgeois exploitation; Buddhism opposses the materialistic and atheistic philosophy of communism.

Can the two survive compatib Iy? The question is most important, as much of southeast Asia appears to be coming under communistic dominance or influence and as Vietnam seeks to feed her territorial appetite on the nations basically in the Theravada Buddhist's sphere. Since the two are inherently opposed, all the conclusions appear negative. Although the Communist Chinese have retained some Buddhist influences, the experiment in China is not yet complete, and Chinese communism and Vietnamese communism may prove to be methodologically different.

Summary

It is evident that Theravada Buddhism has conditioned the pattern of everyday life in Southeast Asia. The religious heritage of the region is rich including elements of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism. All of these beliefs, however, are mutually receptive, rather than exclusive, to one another.

From the early invasion of the Theravada school into Burma, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand, the social, political, and cultural influence has been enormous. This history of each of these nations is saturated with and by Buddhist teachings.

It has also been noted that Theravada Buddhism has been significant in encouraging both cultural change and resistence to change. Entire cultures have been shaped by this religion which influences the way of thinking of millions of people.

It is also clear that as the world experiences increased social change arid as southeast Asian nations seek further moderni~ation, forces negative to the Buddhist tradition are becoming more powerful in the Theravada region. Change is being implemented politically, educationally, and socially, and to remain strong, Buddhism must change also. For instance, the Buddhist orientation is primarily a village tradition; it must also adapt to the urban situation (Pfanner, 1962). The villager's lif~ has traditionally been centered on the monastery, both socially and

148

EAJT / 4:2186

educationally. The increase of urban centers and the availability of non-Buddhist centers of instruction for the teaching of the humanities and sciences will increase the strain on the traditional patterns (Lester, 1973:154). Technology has provided movies, transistor radios, and other amusements decreasing the amount of leisure time spent in the monasteries by the laypeople. Efforts to cope with these changes are seen in the fact that Buddhism has more fully organized in order to adjust and, hopefully, affect to some degree the rapidly changing circumstances.

Final Note

It is difficult to imagine Southeast Asia without the rich tradition of Buddhism continuing to play a major role. Historically, the role has been both fundamental and far-reaching. For the immediate future, it appears that Theravada Buddhism with its heritage and its basic precepts, has as great a potential for continued influence and penetration in Southeast Asia as any other institution. Over the longer scope of the historical future, the horizon appear both tenuous and exciting. As to the outcome, only time will tell with certainty.

GWSSARY

Abhidhamma (PaH) - The third division of the Canon of the Theravada School. It is largely a commentary on the Sutta Pitaka, the Sermons, and subjects them to analysis. Philosophical and psychological, it contains an entire system of mind training.

Amitabka - The Buddha of Infinite Light (as Amitayus). The personification of Compassion. In China and Japan, Amitabka is the intermediary between Supreme Reality and mankind, and faith in him ensures rebirth in his Paradise. In Japan, known as Amida Buddhism.

Amata -:- Immortal, deathless, a name for Nirvana.

Annatta - The Buddhist doctrine of non-ego. The doctrine of the nonseparateness of all forms of life.

Angkor Wat ~ Most famous of a complex of religious buildings in Kampuchean jungle (at Angkor Thorn) dating from the zenith of Khmer rule in the twelfth century A. D.

Asoka - Emperor of India (270-230 B. C.). A Buddhist ruler converted from Hinduism who abolished war in his empire and engraved on rocks and pillars his Buddhist edicts. Played a major role in the initial movement and spread of Buddhism.

Atta - The supreme self. The divine element in man dwelling in each human being. The part of man which perseveres following death in either bliss or misery. (Buddhism does not recognize an absolute personal deity, but does not deny Ultimate Reality).

Authority .:- There is no doctrinally authoritarian figure in Buddhism(i. e., papal concept). Each Buddhistis his own authority and must learn Truth for himself through study, self-discipline, and right practice. No one written teaching or scripture is authoritative in absolute terms.

Bhagavad Gita -:- The "Lord's Song." A treatise on spiritual development along the lines of Karma Yoga, the way of Right Action.

Bhikkhu - A Bhikkhu (monk, priest) is one who has devoted himself to the task of following the Path by renunciation of the distractions of worldly matters.

149

EAJT!4:2186

Bodhi - Enlightenment. The spiritual condition of a Buddha.

Bodhi Tree - Also Bo-tree. The tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment. A fig tree.

Brahma - In Buddhist scriptures Brahma is used as an adjective meaning holy or god-like. In Hinduism, one aspect of the triune god-head with Vishnu and Shiva.

Buddha - A title, not a personal name. Derivation of budh meaning' 'to wake." Gotoma (b. 563 B. C.) was the first to achieve this"wake" and thus is the historical founder of Buddhism.

Buddha-Dhamma - The teaching of the Buddha. The term is most often used in Theravada countries.

Buddhisni - A way of life, a discipline; not a system of dogmas to be accepted by the mind. It is a way to live Reality, and is not ideas concerning the nature of Reality.

Buddhist - One who studies, and endeavors to live the fundamental principles of the Buddhadhamma.

Dhamma - Any teaching by the Buddha which acts as a gu~ding principle for the follower; doctrine.

Dhammapada - The Path or Way of the Buddha's Dhamma or Teaching. The most famous Scripture in the Pali Canon.

Enlightenment - Awakened; freedom from the limitations of the minds and unity with the non-dualistic universe.

Ethics - Every quality encouraging altruism is a virtue; . every opposite quality is a vice. The Buddhist moral code is set forth in the Noble Eightfold Path and the Precepts.

Evil - Buddhism is not dualistic; no division of absolute good and! or evil. Evil is considered as limitation,and therefore, relative; eliminates the "problem" of evil as posed in Western thought. All evil is traced to desire for self (the desire for separateness).

Faith - In Buddhism faith is not the acceptance of doctrinal beliefs, but rather confidence in the Teacher and his Teachings as a Way to a Goal desired.

Four Noble Truths - The basic truths of Buddhism: (I) Dukkha - there can be no existence without suffering: . (2) Samudaya - the cause of suffering is egoistic desire; (3) Nirodha- the elimination of desire eliminates suffering; (4) Magga - the way to elimination of desire is the Noble Eightfold Path.

Hinayana - Small or lesser vehicle (of savlation). Early Hinayana sects numbered eighteen and included Theravada. The Theravada, well established in southern Indian and Ceylon at the time of the Moslem invasion of India, survived the extermination of the other schools of Hinayana, and is the only existing school from the original eighteen Hinayana sects.

Karma (Kamma) - The law of ethical causation; through the operation of Karma a person is "rewarded" according to his deeds, builds his character, determines his destiny, and works out his salvation. Derived meaning, "action and the appropriate result of action."

150

EAJT / 4:2186

Lumbini (Modern Rummindei) - Birthplace of Siddhartha Gautama, who became the Buddha.

Mahayana - The school of the Great(er) Vehicle (of salvation), also called the Northern School. Mahayana is prevalent in Tibet, Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan. For contrast, the Theravada, so far as it recognizes a transcendental Reality, conceives of it as obscured by the phenomenal; in Mahayana, Reality is being ever revealed by the phenomenal. The goal of the Theravada is self-salvation (Nirvana); the Mahayana's goal is renunciation of Nirvana in order to help others in their attempt to reach Nirvana.

Mysticism - An "awareness" of the essential Oneness of the universe and all in it; achieved by a faculty beyond the intellect. A primary element in Theravada Buddhism.

Nirvana (Nibbana) - The supreme goal of Buddhist endeavor: release from the limitations of existence. The Theravana school views Nirvana as escape from life by overcoming life's attractions. The Mahayana school views Nirvana as the fruition of life, the unfolding of the infinite possibilities of the innate Buddha-nature and seeks to remain more "in touch" with life than relinquish all connection with it.

Noble Eightfold Path - The way to Enlightenment; the way of spiritual selfdevelopment. The eight constituent parts are:

1) Samma Ditthi - Right Vision 2) Samma Sankappa - Right Attitude or Motive 3) Samma Vaca - Right Speech 4) Samma Kammanta - Right Action 5) Samma Ajiva - Right Pursuits (including job or livelihood) 6) Samma Vayama - Right Effort 7) Samma Sati - Right Mindfulness 8) Samma Samadhi - Right Contemplation

Pali - One of the basic languages in which the Buddhist tradition is preserved. Pali was adopted by the Theravadins for the preservation of the written Dhamma.

Pali Canon - The Scriptures of the Theravada School. In three divisions or "baskets", a collection of basic writings.

Paramita - Perfection; the six stages (some Buddhists include ten) of spiritual perfection: charity, morality, patience, vigour, meditation, wisdom. The additional four considered by some as an expansion and/or explication of wisdom are: skillful teachings, power over obstacles, spiritual aspiration, knowledge.

Precepts - There are ten moral precepts which are opposed to: (1) taking life; (2) stealing; (3) indulging in sensuality; (4) lying; (5) becoming ' intoxicated by drink or drugs; (6) eating at unseasonable times; (7) attending worldly amusements; (8) using perfumes or wearing ornaments; (9) sleeping on a luxurious bed; (10) possessing gold or silver. In Theravada Buddhist nations, the first five precepts (Five Precepts) are considered the outward form of "the" Buddhist.

Sacred - There is no division life into dualistic concepts of sacred and profane, or good and evil. Veneration is shown for holiness of life, and the virtue of altruism~

151

EAJT / 4:2186

Sutta (Sutra) - Literally a thread on which jewels are strung. The Suttas of the Theravada are the sermons of the Buddha.

Theravada - The "Doctrine of the Elders" who formed the first Buddhist Council. The sole survivor of the eighteen original Hinayana sects; Hinayana being essentially a term of reproach coined by Mahayanists, Buddhists of this persuasion prefer Theravada, a more accurate and less discourteous name (Way of the Elders). Sometimes referred to as the Southern School covering Ceylon, Burma, Thailand, Kampuchea, and has had some influence in Vietnam.

Three Signs of Being - The fundamental Theravada concept of all persons being inseparable from the trilogy of (1) change; (2) suffering or imperfection, and (3) inseverability of life (no separate or immortal soul or spiritual entity).

Uruvela - The place where the Buddha attained Enlightenment under the Bodhi tree.

Wesak (Vesakha) - The month corresponding to April-May celebrating the Birth, Renunciation, Enlightenment, and Pari~bbana of the Buddha.

Yellow Robe - The Bhikkhus of the Thedvada School wear robes of various shades of orange or yellow. These color~ have identified the Theravada Bhikkhus for 2,500 years.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ashby, Philip n, The Conflict of Religion. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1955.

Banks, David 1., Islam and Inheritance in Malaya: Culture Conflict or Islamic Revolution? American Ethnologist Vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 573-586

Barton, R. E, The Religion of the Ifagaos. American Anthropological Association Memoir Series 4:2

Berreman, Gerald, Brahmins and Shamans in Pahari Religion. Journal of Asian Studies 23:53-70, 1964.

Blanchard, Wendell, Thailand: Its People, Its Society, Its Culture. New Haven: HRAF Press

Bradley, David G., A Guide to the World's Religion. New ,Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1963

Brohm, John, Buddhism and Animism in a Burmese Village. Journal of Asian Studies 22:155-168

Brown, D.E., Social Classification and History: India and Bun~a. Papers In Anthropology 18:1 .

Burling, Robbins, Hill Farms and Podi Fields: Life In Mainland Southeast Asia. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1968.

Cady, John E, Southeast Asia: Its Historical Development: New York: McGrawHill Book Company, 1964.

The History of Post-War Southeast Asia. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1974.

Carus, Paul, editor Buddha, His Life and Teachings. New York: Peter Pauper Press, 1975.

152

EAJT 14:2/86

Ch'en, Kenneth K. S., Buddhism. Woodbury NY: Barron's Publisher, 1968:

Ching-Hwang, Yen, The Confucian Revival Movement in Singapore and Malaya, 1899-1911. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. VII, no. 1, pp. 33-57, 1976.

Chuyen., Co Tich, Popular Stories from Vietnam. San Diego State University Press, 1980.

Coedes, G., The Making of South East Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1971.

Conze, Edward, Buddhism: Its Essence and Development. New York: Harper and Row, 1959.

David, Mrs. Rhys, Buddhism, Its Birth and Dispersal. London: Thornton Butterworth Ltd., 1934.

Elwood, Douglass 1., Asian Christian Theology: Emerging Themes. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1980.

Endicott, Kirk, Batek Negrito Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979.

Fall, Bernard B., The Political-Religious Sects of Viet-Nam. Pacific Affairs XXVIII: 235-253

Ferguson, John P. and Christina B. Johannsen, Modern Buddhist Murals in Northern Thailand: A Study of Religious Symbols and Meaning. American Ethnologist Vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 645-670, 1976.

Fisher, c., South East Asia: A Social, Economic, and Political Geography. New York: Dutton Press, 1964.

Frank, Jerome, Persuasion and Healing. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1961.

Gaer, Joseph, What the Great Religions Believe. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1963.

Gard, Richard A., Buddhism. New York: George Braziller, 1962.

Geertz, Clifford, Ritual and Social Change: A Javanese Example. American Anthropologist 59:32-54, 1957.

The Religion of Java. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Religion as a Cultural System. Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion, M. Banton, ed. ASA Monograph #3 London: Tavistock Publications, 1966.

Islam Observed: Religious Development in Morocco and Indonesia. New Heaven: Yale University Press, 1968.

Griffiths, Michale, Changing Asia. Herts, England: Lion Publishing, 1977.

Hall, D. G. E., Burmese Religious Beliefs and Practices. Society for the Study of Religion 40:13-20, 1942.

Harrison, John A., Editor, South and Southeast Asia: Enduring Scholarship selected from The Far Eastern Quality-The Journal of Asian · Studies 1941-1971. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1972.

153

EAJT / 4:2/86

Hickey,Gerald C., Village in Vietnam. New Haven: ·Yale University Press, 1964.

Some Aspects of Hill Life in Vietnam. Southeast Asia Tribes, Minorities, and Nations, Peter Kunstadter, Editor. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965.

HUIIiphreys, Christman, A Popular Dictionary of Buddhism. London: Curzon Press, 1976.

Ikeda, Daisaku, Buddhism, the First Millennium. Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd., 1977.

Ishii, Yoneo, A Note on Buddhistic MilIenarian ·Revolts in Northeastern Siam. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. VI, no. 2, pp. 121-126, 1975.

Jensen, Erik, The Iban and Their Religion. Great Britain: Oxford University Press; 1974.

Kalupahana, David 1., Buddhist Philosophy: A Historical Analysis. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1976.

Kirsh, A. Thomas, Feasting and Social Oscillation: Religion and Society in Upland Southeast Asia. Data Paper Number 92, Department of Asian Studies. Ithaca: CorneIl University, 1973.

Koyama, Kosuke, Waterbuffalo Theology. New York: Orbis Books, 1976.

Kunstadter, P., Editor, Southeast Asia Tribes, Minorities and Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967.

Landon, Kenneth Perry, Southeast Asia, Crossroad of Religion. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1967.

Latourette, Kenneth Scott, Introducing Buddhism. New York: Friendship Press, 1956.

Leach, Edmund, Buddhism in the Post-Colonial Order in Burma and Ceylon. Daedalus: Post Traditional Societies, Pp. 29-54, 1973.

LeBar, Frank,Laos, its society, its culture. New Haven: Human Relations Area File Press, 1960.

Lester, RobertC., Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Ann Arbor: Universi-ty of Michigan Press, 1973.

Ling, Trevor, Buddha, Marx, and God. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1979.

Ling, T.o., A Dictionary of Buddhism. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1972.

Luce, Don and John Sommer, Defending the Interests of the Believers: Catholics, Buddhists, and the Struggle Movement. Vietnam: The Unheard Voices, pp. 105-137. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969.

Manddbaum, David G., Transcendental and Pragmantic Aspects of Relgion. American Anthropologist 68:1174-1191, 1966.

Society in India. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

Moore, Charles A.; Editor, The Indian Mind: Essentials of Indian Philosophy and Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Pre:;s, 1967.

Nash, Manning, Anthropological Studies · in Theravada Buddhism. Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, Cultureal Report Series, No. 13, 1966.

154

EAJT / 4:2/86

Buddhist Revitalization in the Nation State: The Burmese Experience Religion and Change in Contemporary Asia, Robert Spencer, Editor. Pp. 105-122. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971.

Oliver, Victor L., Coadai Spiritism: A Study of Religion In Vietnamese Society. Leiden, Netherlands: E.1. Brill, 1976.

Parrinder, Geofrey, The Faiths of Mankind. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1964.

Paul, Robert A., The Sherpa Temple As a Model of the Psyche. American Ethnologist 3 (l):13H46, 1976.

Pfanner, David E. and Jasper Ingersoll, Theravada Buddhism and Village Economic Behavior. Journal of Asian Studies 21:341-361, 1962

Pitt, Malcolm, Hinduism. New York: Friendship Press, 1955.

Pruess, James B., Merit and Misconduct: Venerating the Bo Tree at a Buddhist Shrine. American Ethnologist 6 (2):261-272, 1979.

Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli and Charles A: Moore, A Sourcebook In Indian Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

Rag, Nihar-Ranjan, An Introduction to the Study of Theravada Buddhism in Burma. Calcutta: Calcutta University Press, 1946.

Sangharakshita, Bhikshu, A Survey of Buddhism. Shambhala Publishers, 1980.

Schecter, Jerrold, The New Face of Buddha. New York: Coward, McCann and Geohegan, 1967.

Sharma, Arvind, Albiruni on Parallels between Hinduism and Christiantiy. The Bulletin of Islamic Studies 1 (1-2), 1978.

Smith, Huston, The Religions of Man. New York: Mentor, 1958.

Smith, RaIph, Relgion. Vietnam and the West. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1971.

Smith, R. B., The Cycle of Confucianization in Vietnam. Aspects of Vietnamese History pp. 1-29, Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1973.

Spencer, Robert E, Editor, Religion and Change in Contemporary Asia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971.

Spencer, Sidney, Mysticism in World Religion. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1963.

Sprio, Melford and Roy D' Andrade, A Cross-Cultural Study of Some Supernatural Beliefs. American Anthropologist 60:456-466

Spiro, Melford, Burmese Supernaturalism. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1967.

Starkes, M. Thomas, Today's World Religions. New Orleans: Insight Press, 1978.

Steinberg, David J., Cambodia: Its People, Its Society, Its Culture. New Haven: HRAF Press, 1959.

Stern, T., Ariya and the Golden Buddha: A millenarian Buddhist sect among the Karen. Journal of Asian Studies 27:297-328, 1968

155

EAJT / 4:2186

Suhrke, Astri, The Thai Muslims: Some Aspects of Minority Integration. Pacific Affairs 43:531-547, 1971. '

Swearer, Donald K., Buddhism in Transition. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1970.

Buddhism. Niles, Illinois: Argus Communications, 1977.

Takakusu, J., The Essentials of Buddhist Philosophy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1956.

Thomas, Ladd, Bureaucratic Attitudes and Behavior as Obstacles to Political Integration of Thai Muslims. Southeast Asia, An International Quarterly Vol III, no. 1

Vos, Howard E , Religions in a Changing World. Chicago: Moody Press, 1967.

White, Peter A., The Lands and Peoples of Southeast Asia. National Geographic l39 (3):296-365

Williams, Lea E., Southeast Asia: A History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

156