South Tyrol. The other side of Italy

description

Transcript of South Tyrol. The other side of Italy

“In the Southern Tyrol, the weather cleared up,

the sun of Italy made itself felt; even at a distance the

hills became warmer and brighter, I saw vines rising on

them, and I could now often lean out of the carriage

windows.”

from: Heinrich Heine, Travel Pictures II, Chapter XIII (1828-1832)

| 5

Introduction: Local colour page 18

Chapter 1 Mountains

Sheer brashness page 21

The Dolomites: The Pale Mountains 22

Myths and fables: Absolutely fabulous 25

King Laurin: The roses have betrayed me 27

Mountain mines: In the bowels of the mountain 30

Perspectives: Sweeping vistas 31

Water: Crystal clear 32

Chapter 2 Joie de vivre

Harmony at the frontiers page 35

Autonomy: Bad times, good times 36

Mediterranean joie de vivre and Alpine staidness: 37

Three perspectives and one fulcrum

Extract from: Joseph Zoderer, Die Walsche (The foreign Italian girl) 40

Ladins: é pa mé da dì – I just want to say 42

Rut Bernardi “la ie pa da rì” (It’s laughable) 43

Knödel and spaghetti: Alpine simplicity and Mediterranean refinement 46

Province capital: Bolzano/Bozen 47

Chapter 3 Landscape

Rural scene page 49

Wine: In the vineyard 50

Recipe: Terlan white-wine soup 53

Törggelen: The fifth season 54

Gardens and spas: The promenades and the Tappeinerweg Trail 57

Apples: Golden orbs 58

Waale – age-old water channels: The farmer as engineer 59

Alpine farms: Summer pastures 61

Bathing culture: Revitalising rural treatments 62

Chapter 4 Eminences

A class of their own page 65

Ötzi: The Man from the Glacier 66

Haflingers: South Tyrol’s equine blondes 67

Castles: Tyrol of yore 70

Romanesque frescoes: Heaven on earth 72

Mountain lifts: Electrical alpenglow 73

Matteo Thun: The consummate designer 74

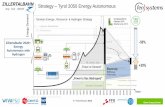

Naturally green: Energy efficiency & renewable energy 77

Chapter 5 Tradition

The art of self-preservation page 79

Alpine farming women: The farming women’s proclamation 80

Customs and traditions: Witching hours 81

Tradition: Red hat band, green hat band 82

Geraniums: The fire in the bay window 86

Dialect: As spoken by South Tyroleans 87

Handicrafts: Skill and dexterity 88

Commentary: The Holey Land 90

Knödel and Speck: Poor man’s fare 94

Chapter 6 A new dawn

A new dawn page 97

The cities: Stadtstiche portraits of cities and villages 98

Architecture: The hot tin roof 100

Contemporary art: Concept art 102

Museums: Showcasing the homeland 103

Messner Mountain Museum: Museum summit 104

Information on South Tyrol page 107

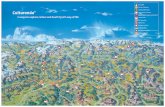

For orientation: at the end of the book you will find a map of South Tyrol to help you to find villages, towns, valleys and mountains. Each chapter contains geographical indications and coordinates under the heading Fact Box (i.e., Bolzano [C4]).

6

Seiser Alm against the backdrop of the Sassolungo and Sassopiatto peaks: Europe’s vastest expanse of Alpine pastureland is a paradise for hikers

| 7

Seiser Alm against the backdrop of the Sassolungo and Sassopiatto peaks: Europe’s vastest expanse of Alpine pastureland is a paradise for hikers

8

Scenic ski runs: Downhill runs, cross-country ski and walking trails, Seiser Alm offers something for everyone in winter, from downhill skiing to cross-country to hiking trails

14

Between heaven and earth: ski slopes, cross-country ski trails, sledding runs with unimpeded views of mountains ranging in elevation from 3,000 to 10,000 feet

16

As far as your feet will take you: South Tyrol’s mountains are connected by 13,000 kilometres of hiking trails

18

Local colourIntroduction

Gritty – that is a good word to describe South Tyrol, the prov-ince of Italy known as Alto Adige in Italian and Südtirol in Ger-man. The region is made of sturdy material; it has structure. Rocks give it its form, quickly changing varieties of stone from porphyry through marble and granite to Dolomite define the landscape and vegetation. The inhabitants have tilled the land with their hands to make the cultivated land alternate with stone, colour and vegetation. Nature and culture intermingle. People keep their traditions and customs alive.New projects are started. In 1999 Count Michael Goess-Enzen-berg decided to extend and modernise his Manincor estate wine cellars near Caldaro, built to designs by Walter Angonese, Rainer Köberl and Silvia Boday. Landscape, history and func-tionality all played a central role in the planning, for it was built by expanding the original edifice. South Tyrolean artist Man-fred Alois Mayr entered the building site at the intersection of the old and new. The painter said he would find the colours himself. At Manincor he removed layers of colour, searched

Local colour | 19

for traces of hues from the history of the wine estate, from the tradition of winegrowing in South Tyrol and documented the building process. Then he presented his colour concept. He wanted to spray a giant wall dividing the old from the new building with Bordeaux mixture – turquoise. His was given the go-ahead. What is more: the counts were enthusiastic. Bor-deaux mixture – copper sulphate and dehydrated lime – was the first fungicide to be used in vineyards and today the old walls in wine estates are still tinged with blue from bluestone. The Enzenberg family owned the copper mine in the Aurina/Ahrntal Valley and, until it closed in 1893 it supplied Bordeaux mixture to winegrowers in all South Tyrol. An example of how history, tradition and progress are inter-twined. Manincor is a South Tyrolean example par excellence, though there are others. They constitute a current of thought and ideas in contemporary culture: South Tyrol is seen as a modern region able to develop its own unmistakable image from its past. “I transport stories with colour”, says artist Man-

fred Alois Mayr. These stories relate tales of nature, the soil, poverty, of the omnipresence of the Church and the pride of a people who have defied emperors, soldiers and dictators and who, to a large extent, now determine their own way autono-mously. The houses were whitewashed, brightly coloured cos-tumes were only worn on Sundays, the Fascists wore black, and their party buildings were Pompeian red. Farmers’ aprons are blue in South Tyrol. Aprons. Boys were given their apron on their first day at school. It was said that a man without his apron is only half dressed. In 1997 the farm-ers in the Venosta/Vinschgau Valley were given a new fruit co-operative. The style of the architect Arnold Gapp was alien to the farmers. Manfred Alois Mayr was once again consulted. He painted a part of the building lapis lazuli blue. At last – painted the colour of their aprons – the building had a proper face for the farmers. They recognized their work in the colour. Sudden-ly contemporary architecture was comprehensible.

Mountains | 21

Sheer brashnessIn South Tyrol all perspectives emanate from the mountains. It was the townsfolk who first climbed the summits and open up unimagined perspectives to the mountain folk.

Nobody knew what it was like atop Mount Ortler until 1804. In that year the chamois hunter Josef Pichler from the Passiria/Passeiertal Valley became the first to climb the summit. He managed to stay there for four minutes. It was icy. He climbed it again in 1805, this time he waved a flag and everybody be-lieved him: Ortler, almost four thousand metres – or over thir-teen thousand feet – high, the tallest mountain in all Tyrol had been conquered. To celebrate the triumph a pyramid of rocks was built rather than a summit cross.The mountain folk in southern Tyrol were not particularly elat-ed at this. Until well into the nineteenth century many people regarded mountaineering as the height of brashness. What was the point? Was there even air to breathe up there? Before 1786 no farmer had ever climbed a summit. Even on the Alpine pastures and passes they believed they had come too close to heaven and erected crosses as a sign of repentance. In South Tyrol there seemed to be a point to excavating tunnels into the mountains to extract silver, copper, marble, but who other than a good-for-nothing would venture up there into the bar-ren world of rock? Either God or the Devil inhabited the moun-tain. No one knew for sure.From this perspective South Tyrol is a veritable paradise for such good-for-nothings. By far the greater part of South Tyrol’sterrain lies above the 3,400 foot elevation line and only 3% of the region is settled. The remainder consists of fields, forest, Alpine pastures and rock. South Tyrol boasts more than 300 three-thousanders (summits exceeding 3,000 metres or 9,843 ft). All perspectives emanate from the mountains. Prospects and vistas. Everything is immediate in South Tyrol, summit and valley, narrow boundaries and vastness. The world-famous climber Reinhold Messner hadn’t even started school when, in his village in the Funes/Villnösstal Valley, he stood beneath the pinnacles of Odle/Geisler and wanted to find out where they finished. The extreme climber Hans Kammerlander was

likewise curious. He climbed his first summit by secretly fol-lowing two tourists up to the Moos-Stock summit in the Tures e Aurina/Tauferer Ahrntal valleys.Townspeople were the first to develop a passion for the moun-tains 200 years ago. They strove for the summits, guided by rural youths. An unlikely rope team resulted: the tourist had the summit in his sights, while the guide was on the lookout for crystals and chamois. One made the summit famous, the other depended on the mountain for his livelihood. In this way people lost their dread of the mountains. All peaks have been climbed and named and entered on maps with indications of their elevations, climbing routes and refuges. People have long realised that mountains did not open their way across the earth’s surface like teeth. South Tyrol’s most famous moun-tains, the Dolomites – officially granted UNESCO World Natu-ral Heritage status in 2009 – even rise as fossilised coral reefs formed at the bottom of an ancient sea. Today everybody can access and experience the mountains in all their facets in safe-ty thanks to walking trails and lift systems. Mountains which once struck awe into beholders are now perceived as beautiful. They have become objects of wonder, as well as leisure, and recreational destinations that must be protected. Vast areas of natural and man-made landscapes have been placed under protection in eight nature reserves and the Stelvio/Stilfserjoch National Park.South Tyrol’s highest mountain, Ortler, finally received a sum-mit cross in 1954. The stone pillar that was initially intended to crown the summit lay packed in crates for years beside the road down in the valley. In 1899 it was erected on Stelvio, the pass that connects South Tyrol with Lombardy, though no long-er as a sign of the mountain having been conquered, but as a monument to the emperor in Vienna.

Chapter 1 Mountains

22

The architect Le Corbusier described the Dolomites as the world’s finest example of architecture. In fact the Dolomites really were ‘built’. They are mountains formed of fossilised algae and coral reefs. They grew for 250 million years at the bottom of the warm Tethys Sea, forced skyward as tectonic plates crashed, finally to stand white and majestically – the Pale Mountains – bizarre and quite different from the surrounding mountains. In 1788 scientists discovered why: the mountains were formed of limestone con-taining magnesium. They were named the Dolomites after the French geologist Deodat de Dolomieu. They became immediately popular, their sagas famous, the crenellated Tre Cime di Lavare-do/Drei Zinnen (Three Peaks) found their way onto postcards and were dispatched around the world, while the famous actor Luis Trenker from the Gardena/Gröden Valley immortalised Sassol-ungo Peak in his mountain films. The Dolomite valleys have been settled since the Iron Age. Rhaetians and Romans, Lombards all left their marks, and in the First World War the front line between the Austrian and Italian armies ran across these mountains. The valleys are inhabited by the Ladin peoples: the oldest settlers in the Dolomites, Ladins are South Tyrol’s third linguistic group.

The DolomitesThe Pale Mountains

Fact Box:» All about the Dolomites at www.suedtirol.info/dolomites» Four of South Tyrol’s eight nature reserves are situated in the Dolomites. www.provincia.bz.it/parchi.naturali

» There are 80 secured climbing routes in South Tyrol, the first of which were built during the First World War along the Dolomite and Ortler fronts. Fourteen Alpine schools offer climbing tours in complete safety.

www.guidealpine-altoadige.it» In Sesto/Sexten, the Bellum Aquilarum Association offers guided hikes

to the World War I museum at Croda Rossa/Rotwand.www.bellumaquilarum.com

Suggested Reading: » Hanspaul Menara, South Tyrol. Paradise in the Dolomites, Athesia 2012 » Gillian Price, Shorter Walks in the Dolomites, Cicerone 2012

Mountains | 25

Nature is in command in the mountains. When she is angry life is terrifying, anyone who tries to oppose her is either a hero or must perish or be punished with perdition. Before science began to explain natural phenomena everyday life was domi-nated by mysterious powers, by spirits which turned the milk sour, by wild men who challenged the gods, by witches who celebrated Walpurgis nights on the Seiser Alm alpine pasture, known as Alpe di Siusi in Italian. These characters feature in countless legends. The same stories were told and embellished over again on long winter evenings. Even today people’s imagi-nations run riot at scenic points or at the sight of rock forma-tions which have given rise to fables. The heart of the great realm of magic lies in the long-secluded Dolomite valleys. For example the pinnacles of Latemar are enchanted dolls, and it is the curse of the Dwarf King Laurin rather than the evening sun that causes the Rosengarten Massif (Catinaccio in Italian) to glow at twilight.

Myths and fablesAbsolutely fabulous

Fact Box:» Read South Tyrol’s legends at www.suedtirol.info/sagas» In search of fables: South Tyrol’s mountains are linked by 13,000

kilometres of hiking trails amid unspoilt nature, five times the distance from Bolzano to London and back. Three hundred such trails meander around Seiser Alm [D/E 5], Europe’s vastest expanse of Alpine pasture-land. The valleys boast 600 kilometres of paved cycle pathways.

www.suedtirol.info/trekking_en

Suggested Reading: » Karl Felix Wolff, The Dolomites and their Legends, Raetia 2012

Mountains | 27

Once upon a time a dwarf king called Laurin lived inside the Rosengarten Massif. He owned immense riches. One of the most precious of these was a magic hood that could make him invisible. There was a magnificent garden in front of the gate-way to his bastion of rock, where myriad roses were in flower all year round, enclosed by a golden thread of silk. Woe betide anybody who dared pick even one rose!One day he caught sight of the stunningly beautiful princess Simhild in a neighbouring castle. He fell in love with her and snatched her away. From then on Simhild was forced to live in Laurin’s kingdom, and there was nothing but sorrow at the castle of her brother, Dietleib. While he was searching for his sister Dietlieb came across the king of the Goths, Dietrich von Bern. With him and other knights he made his way to Laurin’s kingdom.Dietrich marvelled at the magnificence of the roses fenced round by a thread of gold, though his men broke it and tram-pled on the flowers. Beside himself with rage, Laurin came charging at them on his small white steed. It came to an un-equal fight. However, once the knights had pulled off his magic hood Laurin fell to the ground helpless and shouted incensed: “The roses have betrayed me!” Left with no option he led the victors into his fortress where they freed Simhild.Laurin uttered a curse on the rose garden and its beauty was extinguished for ever. He pronounced that nobody, neither by night nor by day, should ever again cast his eyes on the rose garden’s magical splendour. But he forgot to include the twi-light. And that is why the mountain, which is pale during the day, still lights up and glows red as the sun sets.

Fable: King Laurin’s Rose Garden as told by Martin Bertagnolli

28

Nature reserve in the heart of the Dolomites: the bizarre pinnacles of the Odle Mountains in the Funes Valley

30

Dark galleries and the glow from the mine lamp epitomised the life of a miner. For centuries they travelled deep into the bowels of South Tyrol’s mountains to extract copper, lead, zinc and silver. Above ground the miners’ villages developed their own way of life. In its heyday Europe’s highest mine at an eleva-tion beyond 6,600 feet on Schneeberg Mountain employed up to 1,000 men. Today this nether world under Schneeberg in the Ridanna and Passiria valleys, the silver mine at Villandro in the Isarco/Eisacktal Valley and the mining museum at Predoi in the Aurina Valley can all be explored in complete safety wearing a hard hat and head lamp. There is even a cavern deep inside the former Predoi copper mine, which provides hay-fever sufferers and others with a place to breathe allergen and pollen-free air. The main street of Lasa/Laas in the Venosta/Vinschgau Valley is paved white. Laas marble, also known as Lasa marble from the Italian name of the village, is still extracted there. It is held to be the world’s most weather resistant white marble, testi-fied to by the numerous monuments hewn out of this precious rock so beloved by the Habsburgs, in New York, London, Berlin and Vienna.

Mountain minesIn the bowels of the mountain

Craving for the mountain: tank up on energy at dizzying heights

Fact Box: » South Tyrolean mountain mining museum [D2+G1], www.museominiere.it» Silver mine at Villandro [D4], www.bergwerk.it» Lasa/Laas guided marble tour [A3], www.marmorplus.it

Mountains | 31

In the valley, one’s view is drawn upwards by the mountains. High up between the sky and the earth the view is sweeping. From the summit of South Tyrol’s No. 1 ski mountain, Plan de Corones/Kronplatz, the winter views range through 360 de-grees and makes every ski aficionado’s heart beat faster. From the beginning of December to mid-April winter sports enthu-siasts can savour a spectrum of mountain perspectives from 3,300 to 10,000 feet elevations while out downhill and cross-country skiing, tobogganing, snowshoeing, snowboarding and on horse-drawn sleigh rides. The dramatic interplay between the elements expressed by clouds is almost worthy of an Oscar when seen from the Rotsteinkogel summit (4,806 ft) near the mountain village of Verano/Vöran, located between Bolzano and Merano high above the Adige Valley. Artist Franz Messner has set up the open-air Knottnkino (Rock Cinema) here with 40 seats secured to the rocks: until sunset films are ‘projected’ here featuring everything the weather has to offer, against a sweeping backdrop ranging from the Ortler Massif across to the Dolomites.

PerspectivesSweeping vistas

Fact Box:» South Tyrol boasts 30 ski resorts. With a total of 1,200 kilometres of

downhill runs the Dolomiti Superski association comprises the world’s largest inter-connected ski area. The Sella Ronda [F6] circuit leads skiers across four Dolomite passes around the Sella Massif and in summer becomes a challenging circular mountain bike trail. The Ortler Ski Arena comprises 15 areas. The Senales/Schnalstal glacial ski area [B 2/3] near Merano is open almost all year round.

www.suedtirol.info/winter_en» Each year two Dolomite runs host World Cup ski races: the Saslong run

in the Gardena Valley,www.saslong.org and the giant Gran Risa slalom in Alta Badia, www.skiworldcup.it

» The Anterselva/Antholz Valley [G2] is the venue for the annual cross-country skiing Biathlon World Cup. www.biathlon-antholz.it Info for cross-country skiers in South Tyrol at www.suedtirol.info/winter_en

» Tyrol’s very first mountain refuge was built on Mount Ortler [A2] – at the time, Austria’s tallest mountain – in 1805. Today 92 Alpine refuges provide hikers and mountaineers with sustenance and lodging; the most spectacular huts include Becherhaus (10,482 ft/3,195m), Müller-hütte (10,318 ft/3,145m) and Payerhütte (9,908 ft/3,020m).

All refuges at www.suedtirol.info

32

In the beginning water was the landscape designer; humans were at its mercy. Thousands of streams and rivulets in South Tyrol wind or thunder down from mountain to valley. Water trickles from the fountain in every village square. Hundreds of sparkling mountain lakes are catchment basins for snow-melt water. The greater part of South Tyrol’s electricity is har-nessed from the power of water. Drinking water arrives from the spring to the tap in just a few hours without additives or preservatives. Thirty mineral springs are recognised. Their wa-ter has been used since time immemorial for rural and cura-tive baths, or is bottled and sold. The numerous waterfalls are enveloped by a hissing chill, for example in the Gilfenklamm Gorge, Europe’s only marble gorge, near Vipiteno/Sterzing; the waterfalls on the Rein stream near Campo Tures/Sand in Taufers; or the waterfall at Parcines/Partschins which in spring thunders 318 feet to the valley, one of Europe’s tallest. In the Venosta/Vinschgau Valley, water courses flow in a more or-derly manner: centuries ago farmers dug an intricate system of water channels called Waale, the paths running alongside them are now popular and pretty walking trails.

WaterCrystal clear

Fact Box:» Walking recommendations to lakes, waterfalls and alongside Waale

channels at www.suedtirol.info/trekking_en» Lake Caldaro [B5] to the south of Bolzano is the warmest bathing lake

in the Alps. Information on bathing lakes at www.suedtirol.info/swimming

» More on water and mineral springs at www.provincia.bz.it/acqua

Mountains | 33

Well-ordered movement of water: ancient Waal channels irrigate the Venosta Valley and the orchards of Merano’s valley basin

Joie de vivre | 35

Harmony at the frontiersThree intertwined languages and customs, histories which begin to resemble each other. German, Italian and Ladin people live together in South Tyrol. Alpine and Mediterranean

lifestyles have learnt to get along.

When South Tyroleans use the word ‘we’ the meaning could be a little complicated. In South Tyrol, history has brought to-gether three cultural spheres. How do we belong together? South Tyrolean journalist Claus Gatterer (1924-1984) devoted considerable space to this question in his novel Beautiful world, wicked people: “ ‘We’ – they were the people in the valley, ‘our’ people”. In the village of Sexten of the 1920s which Gatterer describes, they were all those who were German, that is, all Ty-roleans, as well as Ladin and Italian people who had long been inhabitants of the valley, just as long as the scissor grinders and pot menders. However there was another ‘We’, the official ‘We’, actually ‘Noi’ – we, the Italians as desired by the Italian state. Claus Gatterer: “They were we, at the time. A bewilder-ing human landscape, a reflection of a muddled time.” South Tyrol’s modern history begins in 1919 when the area to the south of the Brenner Pass was taken away from Austrian Tyrol and annexed by Italy. The new frontier parted the ways of a region that had belonged to Austria for five centuries. The Alpine region has always been a frontier. From the Ro-man perspective the north lay beyond Tyrol, while for the Holy Roman Emperors who travelled to Rome to be crowned by the pope, the south lay beyond the Brenner Pass. This Land im Gebirge or Land in the Mountains, to use Tyrol’s traditional name, was assured a permanent central position in Europe’s power structure by means of two Alpine passes. Merchants, pilgrims, princes with their retinues, adventurers and soldiers passed through Tyrol, paid tolls and customs duties, availed themselves of accommodation and the assurance of safe conduct. European politicians did much to garner Tyrol’s favour, while jumping at every opportunity to conquer the region.

Tyrol was first mentioned in 1271, then in 1330 the houses of Wittelsbach, Habsburg and Luxemburg contended for the hand in marriage of the heiress Margaret of Tyrol. The power-ful made concessions resulting in the granting of Tyrol’s own Magna Carta or Bill of Rights, the Freiheitsbrief of 1242. When Tyrol passed to Habsburg rule the Tyroleans were even ex-empted from military duty on condition that they took charge of their own defence of the province stretching from Kufstein on the Bavarian border to Lake Garda. Tyrol was proud of its special status. As soon as any ruler tried to impinge on their rights the Tyroleans fell back on the old documents. In this frontier region – which Tyrol had been throughout history from a linguistic, cultural and political perspective – every tiny curtailing of liberty was quickly noted and acted upon.The South Tyroleans were not prepared for the events of the twentieth century. The Fascist policy of Italianisation stifled any aspirations towards cultural and political independence. South Tyrol’s struggle for autonomous status was long and hard, but now people belonging to the German, Italian and La-din ethnic groups live together speaking their own respective languages and keeping their own cultures alive. As often hap-pens, people found common ground first of all in the kitchen. Tyrolean housewives tried pasta and minestrone; their Italian counterparts developed a liking for Speck and Knödel. A new at-titude towards life, a new ‘we’ life developed starting with the steam emerging from the cooking pots and grew steadily. This region at the frontier has once again attained a special status.

Chapter 2 Joie de vivre

36

South Tyrol became part of Italy in 1919. As part of the secret treaty of London drawn up in 1915 the future victors of the First World War had promised the Italian delegation a state border at Brennero/Brenner to entice them into the war on their side. Once the Fascists gained power in 1922 they embarked on a harsh programme of Italianising South Tyrol. Anything which sounded German was forbidden. This culminated in the 1939 agreement between Hitler and Mussolini to resettle South Ty-rol’s population in the German Reich. South Tyroleans were faced with the Option: either become completely Italian, renouncing their language and customs, or emigrate. Nazi propaganda proved effective: 85% of German-speaking South Tyroleans opted for the Reich, which by then included Austria. The exit from South Tyrol slowed down after the outbreak of war. After the Second World War Brenner was once again pro-claimed the national border. Protracted negotiations towards achieving autonomous status began, resulting in a second au-tonomy statute in 1972. It took a further 20 years for South Tyrol to obtain complete jurisdiction over all the areas estab-lished in the statute. Today South Tyrol’s autonomous status is regarded worldwide as a model for minorities.

AutonomyBad times, good times

Grüss Gott and Buona sera: both ethnic groups come together for an aperitif

Fact Box:» 510,000 people live in South Tyrol and there are three official langua-

ges: 70% of the population speak German as their mother language, 26% speak Italian and 4% Ladin. About 5% of South Tyrol’s population are foreign citizens.

» More detailed information on South Tyrol’s history at www.suedtirol.info/history

Suggested Reading: » Rolf Steininger, South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century,

Transaction Publ. 2003

Joie de vivre | 37

Landscapes shape people. People shape their environment. In South Tyrol people and the countryside merge seamlessly. At one moment people behave in a down-to-earth Alpine man-ner, the next in an easy-going, carefree Mediterranean way. South Tyrol is characterised by an atmosphere that is difficult to pinpoint, German and Italian headlines at the newsagent’s, a ‘Grüss Gott’ when one had expected ‘Buon giorno’, an in-terplay of atmospheres established, for example by taking a macchiato at 10 a.m., an aperitif after work or playing a game of cards at the regulars’ table in the pub. Germans, Italians and Ladins all have their own histories and memories. As time went by the walls became more leaky, habits and customs be-came intertwined, histories began to resemble each other, even the languages became enlaced. This subject was taken up in literature. Joseph Zoderer wrote two great novels based on German-Italian love relationships that focused on the balanc-ing act between personal affection and collective conformity. Gianni Bianco wrote the first South Tyrolean novel from an Italian perspective.

Mediterranean joie de vivre and Alpine staidnessThree perspectives and one fulcrum

38

Può bastare una parola per entrare in un mondo. Chissà quan-te volte, al supermercato, ci si è trovati davanti a uno yogurt della Mila, la più grande cooperativa lattiera dell’Alto Adige/Südtirol.Ma quando si scopre che quel nome non è nato a caso, perché è formato dalle iniziali della parola “latte” in tedesco e in italiano, si piomba nel vivo della realtà altoatesina. Una terra a cavallo tra due nazioni, Austria e Italia. Un luogo dove si parlano due lingue, anzi tre: perché tra queste montagne vive anche una piccola, ma fiera, comunità ladina. Settemila e 400 chilometri quadrati che si estendono dalle Alpi al fondovalle dell’Adige, dove le diversità culturali sono nette, ma nella vita quotidiana si mischiano spesso.E sin dai tempi antichi. Nel Medioevo le merci tedesche e quel-le italiane si fronteggiavano sotto i portici di Bolzano, ognuna dalla propria parte, perché questo territorio è stato sempre crocevia di scambi e passaggi tra Nord e Sud.Lo scrittore meranese Joseph Zoderer, che pubblica in tedesco e in italiano, dice che si sente nato “tra la neve e le palme. I piedi nell’Adriatico, dietro la schiena una catena di montagne”. E chiunque arrivi qui si accorge subito che anche nel maso del-la valle più sperduta troverà sia canederli che tagliatelle, burro di malga ma anche olio e pomodori. Una terra, l’Alto Adige/

German–Italian conversation in Egna: sports from La Gazzetta dello Sport, local news from the Dolomiten

Joie de vivre | 39

Südtirol, dove vivono tre comunità diverse, ma indissolubil-mente legate dalla Storia e soprattutto dal territorio. Che qui tutti amano visceralmente, e lo si può capire: già solo passeg-giando per Bolzano, alla vista si impone dappertutto un’incre-dibile corona di montagne e i vigneti arrivano fino in città.

IreneMeli,giornalistadiGEOItalia

The foreign Italian girlExtract from Joseph Zoderer’s Die Walsche*

Hanser 1982

*from the German Welsch meaning foreigner – in this case the foreign (Italian) girl; the Anglo-Saxon word “Welsh” to describe the inhabitants of Wales is identical in origin.

Joie de vivre | 41

Recently she had had to shout at Silvano: stay at home until he finally understood. He stayed at home in the Italian neigh-bourhood, which the Germans called Shanghai.I’m a spineless hussy, she maundered as if reciting a litany, almost in the rhythm of the rosary, the murmur emanating from the adjoining room where they had laid out her father, the teacher. She couldn’t forbid Silvano from coming to her father’s funeral – a solemn occasion for a man from the south, a matter of course, of respect and reverence, even though her father had once given the spaghetti Silvano had cooked in the teacher’s house to the wolfhound to eat, placing it on the floor right here beside the living room table; and even though he had regarded the Italian as superficial and full of hot air.She had not treated him like a real person, certainly not like her beloved, but as a Walscher who did not belong here in this world, the German milieu, as one who would be better off staying outside; she had elbowed him out, though in real-ity only pushed him aside; to avoid more trouble she had not let him in, certainly to spare him harassment. She conformed, wronged him, she who had apparently not given a damn and despite the gossip, despite her father’s opposition, had lived as she liked, namely with Silvano who in the end could never

be turned into a German. And she had not married him, she, now in her mid-30s.The burial of her father was expected to signal an end to all this. And so she had to face the approaching clouds alone, and to deal alone with the things which had to be dealt with when somebody dies to live a quiet life. She had come up to this God-forsaken hamlet at one thousand three hundred metres in elevation alone, far away from high and low tide, out of fear for what the others thought, to this mountain dump of a place that her father never managed to get away from, although when he was younger he often proclaimed: Out into the world, out into the wide world at all costs.The place she returned to was not heaven, she knew that well enough. The people had not changed, they had only become outwardly friendlier, and even Ploser had pulled down his old farmstead, house and barn to build a bed-and-breakfast guest house.

42

Ladin is South Tyrol’s third language after German and Ital-ian. Around 18,000 people speak Ladin in the Gardena Valley and the Badia/Gadertal Valley. It is the region’s ancient lan-guage: when the Romans conquered the Alpine valleys their language, Vulgar Latin, became superimposed on the Rhaetian language spoken at the time by the inhabitants of the Alps. Migrating German tribes pillaged and plundered their way south, driving the Ladin people deep into the Dolomite valleys where they preserved their language in seclusion and poverty, developing a rich culture of legends and handicrafts. The Ladin people in South Tyrol were at last recognised as an official lan-guage group in 1951. Today Ladin is one of Europe’s ‘smallest’ languages. The Museum Ladin in the Badia Valley showcases the history of the Ladin people. Once upon-a-time they lived together with the marmots and were one with them, accor-ding to a legend which recounts the origins of the Ladin world; generations of Ladins listened to it on dark winter evenings. The various strands of Ladin have been drawn together to pro-duce a written language. One of its champions is the woman of letters from the Gardena Valley, Rut Bernardi: é pa mé da dì (It’s for me to say).

Ladinsé pa mé da dì – I just want to say

Fact Box: » The Ladin Dolomite valleys embrace the three Italian provinces of

South Tyrol, Trento and Belluno. There are five spoken and written dia-lects, two in South Tyrol: Maréo/Badiot in the Badia Valley [F 3-6] and Gherdeina in the Gardena Valley [E4-F6]. In total around 30,000 people in the Dolomites region speak Ladin.

» The Museum Ladin, located at San Martino in Badia [F4] provides vivid insight into the history and culture of the Ladin people. www.museumladin.it

Joie de vivre | 43

Extract: Rut Bernardi, ‘Das ist doch zum Lachen’ (It’s laughable), 2007 from: Dolomite a summit book, p. 98

It’s laughableI just want to sayone just has to accept it and goone still doesn’t knowhow to have it said to youone day or perhaps notyour head doesn’t follow your own foot

It’s no laughing matterif neither you noryour child can say itone just has to accept itand cannot reject itone has to repeat it

la ie pa da rì

é pa mé da dìla ie da tò y jìn ne sà pa cofé a dì mo a vóte n di o nol cë ne va pa méa jì do si pe

la ne ie pa da rìco ne sà no ëiy no si fi da dìla ie mé da tòy de ne dì no: oh

da dì dò

44

Ortisei in the Gardena Valley is called St. Ulrich in German and Urtijei in Ladin: South Tyrol’s languages, German, Italian and Ladin co-exist most immediately here

46

The climate on the southern side of the Alps has always pro-vided a wealth of ingredients historically not available in north-ern countries, and South Tyrol’s cuisine was influenced by the Mediterranean diet long before the region became part of Italy. The region’s cuisine is no longer the rather substantial fare needed to sustain mountain farmers as they toiled on the steep slopes, but has evolved in response to modern demand for elegance and delicacy. Some chefs prefer to specialise in Tyrolean, Ladin or Mediterranean cuisine, while in many res-taurants Italian and local dishes coexist on menus as equals. Certain ‘poor man’s’ dishes made from leftovers have become delicacies, even served in Michelin-star restaurants, such as Knödel dumplings typically made from stale white bread, now served in myriad variations (i.e., plain, Speck, beetroot, cheese, ricotta and spinach). South Tyrol’s identity question is re-solved, at least at the dinner table.

Knödel and spaghettiAlpine simplicity and Mediterranean refinement

Identity in the kitchen: a mixture of Italian, Ladin and Tyrolean fare

Fact Box: » Each year more and more Michelin stars are showered upon South

Tyrol’s restaurants – 23 stars in 2014. » Further information of South Tyrol’s gastronomy and recommendations

at www.suedtirol.info/foodandwine

Suggested Reading: » Heinrich Gasteiger/Gerhard Wieser/Helmut Bachmann, 33xSouthTyroleanClassics, Athesia 2010

Joie de vivre | 47

South Tyrol’s province capital, Bolzano in Italian and Bozen in German, is the place where the German and Italian languages and cultures coexist most closely. This is reflected in the city’s architecture. A century ago Bolzano, an old trading city with its arcaded walkways from the late Middle Ages, its building facades strongly inspired by northern Europe but with south-ern influences, was almost entirely limited to the eastern side of the River Talfer: across the river there were just fields and orchards. From 1922 Bolzano was redesigned, the Fascists wanted to use the city as a bridgehead to conquer South Tyrol. The città nuova or New City to be built on the western side of the River Talfer was designed in a new, rationalistic style of architecture aimed at symbolising modern Italy. The regime’s star architects, including Marcello Piacentini, worked on the project. As a result the new part of the city is characterised by an almost complete ensemble of Fascist ‘power architecture’ unique in Italy. Here an Italian aura envelops everything in con-trast with the city’s historical centre: the bars, pubs, shops and the attitude towards life. Politically the new streets were an affront, though kept in perspective they froze the history of a city and its region, embellishing little Bolzano with an element of modern urbanity. The best view of the city’s two faces is provided by the newly built Museion, the museum for modern and contemporary art, set against the breathtaking backdrop of the nearby Dolomite Mountains.

Province capitalBolzano/Bozen

A question of style: both German and Italian masters worked on Bolzano’s Gothic cathedral

Fact Box:» South Tyrol’s province capital Bolzano [C4] has 100,000 inhabitants:

73% belong to the Italian ethnic group, 26% are German and 0.7% Ladin. Around 30% of all foreigners in South Tyrol live in Bolzano. Information on history, sights and events at www.bolzano-bozen.it

Landscape | 49

Rural scene

There was a time when this region was terribly beautiful. Ter-ribly because travelling downhill from the Brenner Pass the rocks came closer and closer to the road, there were constant landslides and travellers encountered “a bleeding Saviour eve-ry quarter of an hour”, as Louise von Göchhausen wrote in her Journey to the South in 1788. Beautiful because the same rocks evoked grandiose sensations. Terror prevailed for a long time. Who could live there? The Medici duke Cosimo III only just sur-vived a rock fall. Goethe rode through the night in haste from Brenner towards the South on his Italian Journey. Only when he was south of Bolzano did he observe: “Everything which tries to vegetate in the higher mountains has more strength and vi-tality, the sun shines hot, and one comes to believe in a God once again.” Nature is under control; we can once again walk the earth in safety. This region rises skyward almost everywhere. The landscape embraces the whole gamut of vegetation, from the sub-Med-iterranean to arctic tundra. A single view takes in palm trees and glacier ice. Alpine ruggedness yields to smooth contours. The Alps protect South Tyrol from the northern winds and the air is immediately milder, the light more brilliant, not a great feat with 300 sunny days per year; The South is close and pal-pable. Vines climb the slopes overlooking the Adige and Isarco rivers, accompanied by apricot, apple and pear trees, inter-spersed with almond, cypress and fig trees. Asparagus is in season in spring, chestnuts in autumn.South Tyrol’s landscape is a mosaic rich in contrast. Each piece of earth has been wrested from nature, the geology and climate change in the tiniest areas, often from vineyard to vineyard,

farmstead to farmstead. In the Isarco and the Venosta valleys, fruit and grapes are grown at elevations reaching 3,300 feet. In Italy’s northernmost winegrowing areas vineyards reach into distinctly Alpine scenery, with drastic differences between day and night time temperatures, yielding wines which are among Europe’s most aromatic with vibrant acidity. Above 1,000 me-tres elevation (3,281 ft) the main activities are arable and live-stock farming. In early summer animals and their herdsmen set off for the high pastures. Townspeople have been leaving for medium altitudes to escape the summer heat for centuries, farmers extend their pastures to well beyond the tree line. The grass is better there, life more frugal. Terrible or beautiful?In around 1800 a new ideal of beauty germinated in Europe’s well-heeled society. By then mountains were deemed beauti-ful, fresh air made the body, the lush vegetation and the soul beautiful. The routes into the valleys had become safer. This was Merano’s heyday. According to the 1821 Yearbook of Ger-man Spas, the town with the mild winter climate had become a place “where fashion wills you to become healthy”. Dung heaps and henhouses vanished from the town, in future the only scents were to be those emanating from the fragrant promenades. Spa guests’ first assignments were taking walks and eating grapes; for a time they were even allowed to pick the grapes themselves. Many wallowed and were awestruck by the scenery, few conquered the summits. Subsequently travel-lers came into the region and did not want to continue their journey south.

Chapter 3 Landscape

50

Lagrein, Vernatsch and Gewürztraminer: these are three grape varieties that are native to South Tyrol. Each performs well, though in different conditions: Lagrein loves hot, eroded red porphyry soils. Gewürztraminer prefers clay, while Vernatsch yields best results on alluvial, gravelly soils. In a region where only a tiny area can be cultivated and with correspondingly high costs, wine producers can only survive by producing top qual-ity. At elevations between 700 and 3,300 feet above sea level the soil compositions and micro-climates vary enormously; the only constant is the 300 sunny days per year. The result? Twen-ty different grape varieties yield Alpine wines with Mediterra-nean charm. Around two-thirds of the region’s total wine pro-duction comes from wineries located along the South Tyrolean Wine Road: the scenic route meanders from Bolzano/Bozen to the rolling hills of Appiano/Eppan and Caldaro/Kaltern as far as the province’s southern border, providing views of histori-cal wine villages and ultra-modern wine estates. This is where the Romans learnt to store wine in wooden casks; monaster-ies in southern Germany later founded their wine estates in southern Tyrol. In South Tyrol grapes grow where one would least expect: the province capital, Bolzano, is the region’s third largest winegrowing municipality.

WineIn the vineyard

Bestsite:over20grapevarietiesyieldAlpinewineswithMediterraneanallure

Landscape | 51

Fact Box:» Vineyard area: 5,300 hectares, 98% of the total area under grape

cultivation is registered for the production of DOC wines; South Tyrol offers a variety of 20 types of grapevines. Around 60% of the area is planted with white and 40% with red grape varieties; average annual production is about 340,000 hl, corresponding to 0.8% of Italy’s total wine production; seven sparkling wine producers together make around 250,000 bottles per year using the classic method of secondary fermentation in the bottle; last year 27 South Tyrolean wines were awarded the highest accolade, Tre Bicchieri, by Italy’s top wine guide, Gambero Rosso – I Vini d’Italia 2014. Further information on South Tyrol’s wines available at www.altoadigewines.com

» Three monasteries in South Tyrol make wines from their own estates, each with its own specialities: Muri Gries in Bolzano [C4] specialised in red wines, www.muri-gries.com, the Augustinian abbey called Novacella/Neustift [D3], near Bressanone/Brixen, which specializes in white wines, www.kloster-neustift.it, the monastery cellars of Pircher in Lana [B4] specialised in distilling superb brandies, www.pircher.it

» The Bolzano Wine Tasting (Bozner Weinkost) is the most important event showcasing South Tyrol’s wines, www.weinkost.it. The interna-tional Merano WineFestival showcases European wines in general. www.meranowinefestival.com

» South Tyrolean marc brandies are made exclusively from South Tyrolean grape skins. www.suedtirol.info/grappa_en

52

“The typical red wine is lightly earthy in its earthly nature, manly in character, austere to rough-hewn, like a strong labourer’s hand. A Vernatsch wine such as Kalterer See always remains a youth with a downy beard, while Lagrein is born with hair already on its chest.”

Klaus Platter, winemaker and former director of Laimburg Province Winery, sees human traits in wine.

Designer label signed by the artist: Paul Flora’s Gschleier Vernatsch wine label for the Girlan winegrowers’ co-operative

Landscape | 53

Sauté the croutons in butter until golden and sprinkle with cin-namon. Pour the meat stock and wine into a saucepan. Beat the egg yolks with the cream and add to the soup. Heat the mixture over a low flame and continue stirring until it becomes creamy. Season with salt and a little nutmeg and cinnamon. Pour into soup bowls and serve garnished with croutons and a pinch of nutmeg and cinnamon.

Recipe: Terlan white-wine soup½ l meat broth4 egg yolks50 ml cream¼ l Pinot Bianco from Terlano/TerlanCroutons made from stale white bread Roll, crust removed1 tbs. butterGround cinnamon, freshly grated nutmeg, salt

54

It is autumn. The grapes have been picked and crushed. Accord-ing to legend this is the time when dwarfs, the Wein-Nörggelen, come down from the mountains, drink the new wine and even steal it. Their thirst for the new wine knows no bounds and while the dwarfs go about wine filching, the humans go Törgge-len. The name of this South Tyrolean custom derives from the Latin word for wine press, torculum, which passed into South Tyrolean as Torggl. The tradition of Törggelen is thought to have begun in the Isarco Valley: winegrowers sent their livestock to the high pastures in the care of mountain farmers, who were regaled with farmhouse fare and new wine on their return in autumn. Or perhaps the farmers simply celebrated a success-ful harvest, met to taste and compare each other’s new wine. In its modern form, Törggelen begins with a bracing walk up to a farmhouse tavern called a Buschenschank and ends with sa-vouring local fare and new wine or grape juice along with roast chestnuts in good company. The main course was traditionally Speck ham and Kaminwurzen (smoked sausages). Today guests can choose from the entire range of South Tyrolean rural fare: barley soup, boiled bacon, boiled sausage, sauerkraut and Knödel dumplings; and for dessert, sweet Krapfen – deep-fried pastries filled with jam.

TörggelenThe fifth season

Fact Box:» Chestnuts play an important role in the Törggelen custom. Chestnut

trees have been cared for since the Middle Ages; they were often han-ded down as an inheritance and were regarded as a farmer’s old-age pension. There are chestnut trails at Lana [B4] between Bolzano and Merano and in the Isarco Valley [B 3/4] where plenty of information on chestnuts can be obtained. More on Törggelen at

www.suedtirol.info/toerggelen_en» A Buschenschank is a rural tavern in a wine-growing area, where guests

enjoy rustic cuisine and homemade wine. www.redrooster.it

Landscape | 55

Flame-roasted: chestnuts, called Keschtn locally, are just as much a part of Törggelen tradition as the sweet fresh grape must called Sußer

56

Eighty cultivated landscapes from all over the world and a museum in the castle: the Gardens of Trauttmansdorff Castle in Merano

Landscape | 57

Not hot, not searing, the air in Merano/Meran is just right for well-born sallow consumptives. The physician who first sci-entifically studied this phenomenon was a private physician and was consequently genuinely interested in his patients. Empress Elisabeth of Austria followed in the wake of Princess Schwarzenberg in savouring Merano’s salubrious climate, fol-lowed by prominent guests including Schnitzler, Rilke, Kafka to mention just a few. By 1900 Merano had become an inter-national spa resort for the nobility. The riverside area where Merano’s washerwomen bleached linen has given way to the famous spa promenade – one promenade for the winter, an-other for the summer. The Tappeinerweg Trail leads up along the side of Küchelberg Mountain overlooking the city, one of Europe’s longest promenades known simply by the locals as the Tappeiner. Similar pathways were built in Bolzano. Walks in the open air were prescribed to guests, who took walks at the foot of the glaciers beneath blossoming winter magnolias, palms, cactuses, olive trees, drank sour whey in Merano or ate ‘curative’ grapes, up to three kilos per day. Today Merano is still a combination of air, landscape and architecture. Plants from all over the world thrive at the botanical Gardens of Trautt-mansdorff Castle. A nostalgic walking trail called the Sissiweg leads from there into the city as far as the new thermal baths, the Terme Merano. Take a little ‘me time’ and the atmosphere of the belle époque returns immediately.

Gardens and spasThe promenades and the Tappeinerweg Trail

Fact Box:» Information on Merano’s [C3] promenades at www.merano.eu» The Gardens of Trauttmansdorff Castle was named International

Garden of the Year in 2013. South Tyrol’s museum of tourism, called the Touriseum, is housed inside the castle. www.trauttmansdorff.it,www.touriseum.it

» The Terme Merano swimming and spa complex was designed by star architect Matteo Thun. Natural South Tyrolean products such as grapes, hay and whey are used in treatments in the spa department. The Terme Merano’s own apple cosmetic line is new. Information at

www.termemerano.it» The labyrinth garden at Kränzelhof Wine Estate at Cermes/Tscherms

[B4] near Merano is ideal for meditation and self-discovery. The maze comprising vine hedges of ten grape varieties form the heart of the complex. www.labyrinth.bz

58

South Tyrol’s orchards fill the central valleys. Some 40 million apple trees thrive in the Adige Valley between Salorno/Salurn in the south and the Venosta Valley in the west, and in the Eisacktal’s Bressanone valley basin. Together these orchards comprise Europe’s largest self-contained apple growing area. The warm, sunny climate with 300 sunny days per year give the apples the appropriate sweetness and colouring, while the chilly nights provide for their fresh aromas, tangy flavour and crunchy pulp. In all, 16 varieties are grown at altitudes rang-ing from 700 and 3,300 feet above sea level; the best known are Golden Delicious, Gala, Red Delicious and Braeburn. The climate is both the fortune and bane of the fruit growers: the farmer is on his guard while cyclists and walkers relish the white splendour of the valley and hillsides ablaze in blossom against the backdrop of snow-clad mountains, for frost may strike even in mid-May. When it does, overhead irrigation sys-tems are turned on, cocooning the fragile blossoms in delicate cases of ice, to thaw out unharmed in the morning sun. Farm-ers usually sense the weather in advance. Between mid-August and the end of October 900,000 tonnes of apples are harvest-ed in South Tyrol, corresponding to one tenth of the entire EU apple crop. Around half of the harvest is exported. Southern Tyrol began exporting fruit as long ago as the sixteenth cen-tury, with express delivery companies transporting the Alpine-Mediterranean apples to the courts of Austria and Russia.

ApplesGolden orbs

16 apple varieties, 40 million apple trees: every tenth European apple comes from South Tyrol

Fact Box:» Information on apple cultivation and excursions and walks in the apple-

growing areas at www.suedtirol.info/apple» The Terme Merano [C3] makes its own line of cosmetics using

exclusively South Tyrolean apples. www.termemerano.it

Landscape | 59

South Tyrol’s western valley system, the Venosta/Vinschgau Valley, lies in the rain shadow of incredibly high summits ex-ceeding 12,000 feet. As a consequence the region is semi-arid with rainfall levels of around 500 millimetres per year, simi-lar to Sicily. Centuries ago innovative farmers endeavoured to make their fields fertile by diverting glacier water from streams in the high mountains through an intricate system of water channels complete with weirs and sluice gates, some measuring over 10 kilometres. They are often visible as green strips across the otherwise steppe-like landscape of the aptly named Sonnenberg (Sun Mountain). The use of the water was subjected to bylaws overseen by a Waaler, who traditionally allocated the flow and checked for damage, etc. Sheep were allowed to drink the water for as long as it took the shepherd to eat his hard Paarl bread rolls. The system worked well. Corn from Sonnenberg Mountain was highly sought after and ex-changed against wine from Caldaro. Today apple orchards have replaced cornfields and are irrigated using modern state-of-the-art methods, making the Waale redundant. Several are still lovingly maintained and their maintenance pathways provide relaxing walks.

Waale – age-old water channelsThe farmer as engineer

Fact Box:» Information on Waal pathways in the Venosta Valley [A/B 1-3] at www.venosta.net» South Tyrol sculpture pathway: the landscape art project at Lana [B4]

near Merano leads beside the Brandis Waal in places and is one of South Tyrol’s finest walks. www.lana-art.it

» A department of the Vintschger Museum at Sluderno/Schluderns [B2]is dedicated to water. www.altavenosta-vacanze.it

Landscape | 61

Early summer is the time to make the first hay to feed live-stock through the winter. To save it, sheep, goats, calves and numerous cows are driven up to summer pastures called Al-men, often beyond the timberline where they find ample graz-ing. Their ‘summer holidays’ last three months, during which herdsmen live a simple life in seclusion. All help with milking and the Senn, a kind of dairyman, makes butter and cheese, and cooks. Today the occupants of these picturesque log-built farmhouses offer hikers a place to rest and savour Alpine fare: Schmarrn (shredded pancake), Knödel dumplings, Melchermuas pudding or Speck with fresh mountain cheese and crispy Schüt-telbrot. The use of these summer pastures is as old as the set-tlement of the mountain region. Depending on the area, the Almen belong to individual farmers or are owned communally. For centuries some 3,000 sheep have been driven from the Se-nales Valley across the 9,950 foot-high Hochjochferner Glacier to their summer pastures in Austria’s Vent Valley. Their de-parture in June and return in September are truly spectacular events. The trek across snow fields, rock and ice gullies takes two days. In almost all valleys the animals are greeted back in autumn with a lavish festival, a parade of livestock and herd-ers, led by a decorated cow called the Kranzkuh. The animals are reclaimed by their owners, butter and cheese wheels are divided among the farmers, the hands and herders receive their ‘mountain money’ and the Kranzkuh’s garland is hung over the cowshed door.

Alpine farmsSummer pastures

Fact Box:» South Tyrol’s Alpine pastures are situated above the timberline, where

each year some 95,000 animals spend the summer months. Grazing protects the landscape from erosion and becoming overgrown, keeping the high regions accessible as a place for leisure and relaxation. The Almabtrieb or return to the valley takes place between early September and the beginning of October. Alpine pasture walks at

www.suedtirol.info/trekking_en» South Tyrol is home to 80,000 milk cows. Their milk is processed into

butter, cheese and yoghurt. More information at www.suedtirol.info/milk» The Almencard in the Gitschberg-Jochtal area [D/E 2-3] offers free gui-

ded walks to 30 alpine farms and pastures, the use of three cable cars and participation in events. www.malghe.it

62

According to rural custom there’s an herb for every ailment. Farmers noticed this long ago. Hay packs were applied wher-ever they felt a dragging pain and those who could afford it slept on a hay mattress, unlike the farm hands who slept on straw. Then, around a century ago, the hay bath was discov-ered: after a long day’s toil haymakers on the Alpine meadows retired worn out to a bed of fresh hay and were surprised when they woke up completely revived, all aches and pains gone. When summer went, so did the beneficial effects of wilting hay which, when it is warmed, releases the fragrant compound coumarin, vitamins, tannins and essential oils which combine to soothe rheumatic and muscle pains, stimulate circulation, strengthen the immune system. Today hay baths can be taken all year round, as warmth and moisture are introduced to the hay from external sources. Back in the Middle Ages Tyrolean farmers took time for a Badl, in those days a water bath. Even servants had a right to a bathing holiday. The Ultimo/Ultental Valley became famous for its nine baths. Later the German chancellor Bismarck fell head over heels in love there. It could have resulted in a wedding had Bismarck not been such a staunch Protestant and the potential bride’s father from the Ultimo Valley such a devout Catholic.

Bathing cultureRevitalising rural treatments

Fact Box:» The hay, herbs and flowers that go into a hay bath are sourced from

unfertilised Alpine meadows. The most important include lady’s mantle, mugwort, yarrow, pasque flowers, arnica, gentian, primroses, soapwort and various types of buttercup. Find farmsteads and hotels offering hay and water baths at www.suedtirol.info/wellbeing

64

He has climbed all 14 of the world’s eight thousanders and the peak of fame at the same time: Reinhold Messner

Eminences | 65

A class of their ownIn South Tyrol all paths lead upwards. It is in people’s character. The trick is to keep ahead of the others. There are South Tyroleans without equal, and

others who fear no comparison.

This brings us to the heroes. Or perhaps ‘originals’ would be a better word. At one time court Tyroleans were kept by the city dwellers to provide entertainment with jokes and yodel-ling performances. Südtiroler (South Tyrolean man) and Südti-rolerin (South Tyrolean woman) were common job names. They were, of course, inglorious originals. These South Tyroleans were poor but resourceful, making their origin their job and at-tracting attention. Today’s South Tyrolean originals do not sell themselves cheaply, though even they are preoccupied with their origin, with their environment, their homeland’s history, with the instincts and stubbornness of the inhabitants.Reinhold Messner and Ötzi – both are unique. The once-in-a-lifetime climber encountered the moist mummy before it was discovered on the Similaun Glacier. Messner is one of South Tyrol’s harshest critics, though also a staunch South Tyrolean, while if Ötzi had made it onward for another 92.56 metres to the border he would now be an Austrian. Ötzi and Messner represent two elements of an immense theme: in South Tyrol the mountains are omnipresent. During the 1930s Luis Trenker, South Tyrol’s mountaineering freak par excellence, brought the colossuses to life on the silver screen. He set new stand-ards for films in which mountains play the leading role.As an element of nature, the mountain sets the rules and man adapts. For example Haflinger horses were first bred as mountain working horses and for military purposes. Refuges that cling to the rock faces at altitude, and audacious cable car systems prove that the mountains can be conquered. At the same time, South Tyrol’s nature is its powerhouse: sun, forest, and water propel the province to sustainability. Currently, 40% of South Tyrol’s energy needs are being met through renew-able energy sources. This also gives rise to a certain amount

of hubris: 90% of ski runs are covered by snow-making sys-tems. South Tyrol is a world leader in developing snowmaking technology, though also adroit in demonstrating that artificial snow is made from clean water: chef Martin Mairhofer in the Pusteria/Pustertal Valley serves sorbets made using pure arti-ficial snow.Retaining the view of the valley from a high vantage point. In medieval times many powerful local rulers spied from castles high up on the mountainsides and decided who should be al-lowed to pass through Tyrol and who not. So many that South Tyrol boasts the highest concentration of castles in all Europe. As trade and politics found new routes the Tyroleans were left alone among themselves, cut off from sources of easy money. Lack of money resulted in several artistic gems surviving, for example Romanesque frescoes in the Venosta/Vinschgau Val-ley which can still be admired simply because in the seventh century there was no money available to have the churches repainted.Nature also holds several records, such as the Dolomites, the 2,000 year-old larches in the Ultimo/Ultental Valley, the steppe plants on the Sonnenberg Mountain in the Venosta Val-ley, the 350 year-old vine at Prissiano/Prissian above the Adige Valley which still yields its owner an abundant supply of wine. The pinnacle of fame is climbed by sure-footed personages like Ötzi and Reinhold Messner. In the same way, architect and designer Matteo Thun fits perfectly into this landscape, as do his concepts. The Kastelruther Spatzen with 15 million records sold are one of the most successful traditional folk groups in the German-speaking area. The composer and Oscar winner Giorgio Moroder from the Gardena Valley and nephew of Luis Trenker revolutionised disco music. He lives in Los Angeles but remains an original South Tyrolean.

Chapter 4 Eminences

66

He ‘lives’ under extreme conditions, behind eight-centime-tre-thick bullet-proof glass at minus six degrees centigrade and in an atmosphere of 98% humidity. The purpose of this chamber in the Archaeological Museum is to replicate the conditions prevailing in the rock hollow in the Senales Valley glacier where a German couple discovered Ötzi in 1991. It was only when his naturally mummified remains were examined in a laboratory that the sensation became apparent: the man from the glacier lived 5,300 years ago. He is the world’s oldest moist mummy. He had been consumed by the ice 600 years before King Cheops had his pyramid built in Egypt. We now know he was being pursued up into the high mountains where he knew the terrain, and was murdered. He is a long-term pa-tient for scientists, who expect Ötzi to supply new impulses in the spheres of anthropology, genetics, and medicine. Research into Ötzi’s DNA is hoped to result in new findings in the sphere of hereditary diseases and conditions such as Parkinson’s or infertility. Sets of operating instruments made of titanium and other precision implements have been developed especially to carry out research into Ötzi. Ötzi’s life and times have been vividly brought to life in the interactive ArcheoParc museum in the Senales Valley near Merano.

ÖtziThe Man from the Glacier

Fact Box:» The mummy was nicknamed Ötzi because the glacier in which he was

discovered is in the Ötztal Alps.» The mummy and the objects he was carrying on his person – an axe,

bear fur cap, clothing, bow and arrows – as well as a life-size reconst-ruction can be seen in the Bolzano Archaeological Museum [C4]. www.iceman.it

» Information on the ArcheoParc [B2] interactive museum at www.archeoparc.it» EURAC Institute for Mummies and the Iceman coordinates and

documents all research projects in co-operation with the Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano. Ötzi has been photo-documented from twelve perspectives with zoom and 3-D functions, all of which can be seen at www.eurac.edu

Suggested Reading: » Angelika Fleckinger, Ötzi, the Iceman. The Full Facts at a Glance, Folio 2011

Ötzi sensation: in Bolzano, the world’s oldest moist mummy undergoes research and fires the imaginations of visitors

Eminences | 67

The Haflinger is South Tyrol’s very own horse breed and an all-rounder per excellence: attractive in appearance, sturdy, impeccable in character, a strong-nerved leisure and family horse. The first Haflinger was named 249 Folie, born in 1874 in the Venosta/Vinschgau Valley, the son of an Arab stallion and a local brood mare. The ministry for military and agricultural af-fairs set up stud farms all over Austria. Strong draught and war horses were required. The Venosta breeder passed muster. His golden chestnut horse met the Austrian army’s perception of the ideal military horse and was described as a “beefcake with Arab nobility”. The new foals were bought mainly from farmers on the Tschögglberg Plateau, overlooking Merano, where the village of Hafling is located, hence the name Haflinger. Farm-ers carried spa guests from Merano up to the cooler heights on Haflinger horses. Later on, breeders from the Sarentino/Sarntal Valley selected animals to produce the characteristic blond mane.

HaflingersSouth Tyrol’s equine blondes

Fact Box:» Information on riding stables and riding schools in South Tyrol at www.suedtirol.info/horseriding» The South Tyrolean Haflinger Breeders’ Association provides information on the history of the breed at www.haflinger.eu» The farmers’ galloping race with Haflinger horses at Merano Race-

course [C3] looks back on a long tradition. The racetrack is one of Europe’s finest, specialising in steeplechases. www.meranomaia.it

70

In medieval times Tyrol was an Alpine choke point between north and south, and as such was continuously fought-over. Emperors and popes courted the favour of allies, and local nobles outrivaled each other. Castles were built to oppose castles; country houses were fortified. Many fortresses sat defiantly on rock spurs, today fortified manors nestle amid lush vineyards. Some house museums, while others have been transformed into hotels and restaurants. South Tyrol boasts the highest concentration of castles and sumptuous fortified country houses in all Europe, 450 in number. The first and larg-est was Sigmundskron Castle to the south-west of Bolzano, mentioned in 945, while over two centuries later Tyrol Castel overlooking Merano became the centre of political power as the family seat of the Counts of Tyrol. Later in the fifteenth century, as history had moved on, the powerful Tyrolean class-es declared that they would only swear allegiance to the own-er of Tyrol Castle. Today the castle houses the South Tyrol’s museum for regional history. Churburg Castle at Sluderno/Schluderns in the Venosta Valley is a real gem. Rebuilt in the Renaissance style in the sixteenth century, it now houses an impressive private armoury. However, by far the finest depic-tions of everyday courtly life in the Middle Ages are contained in the secular frescoes in Runkelstein Castle in Bolzano, and in Rodenegg Castle near Bressanone.

CastlesTyrol of yore

Fact Box:» 150 of South Tyrol’s 450 castles and noble residences are open to the

public; 80 are residences. Appiano [B4] is the municipality with the most castles and aristocratic country houses: 180 in an area with just 13,000 inhabitants.

» Addresses of castles and noble residences as well as castle hotels and restaurants can be found at www.suedtirol.info/castles

Eminences | 71

Merano and Environs: Lebenberg Castle above Cermes was built in the thirteenth century

72

Around 1200: pilgrims are everywhere, all searching for God. Churches, monasteries and convents are painted with depictions of heaven and hell in the most striking colours. The Venosta/Vinschgau Valley, the region’s westernmost, is South Tyrol’s nucleus of Romanesque fresco painting. The quality of Romanesque art has survived better here than anywhere else, with a concentration without comparison in Europe. Marienberg Abbey near Malles/Mals forms the un-surpassed opening. The crypt frescoes served as a model for the painters of the Monastery of St. John in the neighbouring Müstair Valley, Switzerland and for the chapel of Hochep-pan Castle to the south of Bolzano. Monte Maria paintings also influenced those in the small church of San Giacomo/St. Jakob on Kastelaz Hill at Termeno/Tramin in the southern part of South Tyrol. In those days nobody spoke of freedom in art. The Church determined the subject matter, the person commissioning the painting decided the motifs and the paint-ers executed the task. The patron’s sense of fashion is evident in the chapel of Appiano Castle: Ulrich von Eppan was a pas-sionate crusader and brought home with him samples of the latest Byzantine craze. In those days the Byzantine style was the standard in western painting. Influences are found in the Chapel of San Giacomo near Glorenza/Glurns and in the mys-terious frescoes in the Prokulus Kirche church at Naturno/Naturns near Merano.

Romanesque frescoesHeaven on earth

Fact Box: » The Stairways to Heaven project has drawn up a route linking the most

interesting cultural sites with Romanesque art in South Tyrol, Graubün-den (Grisons) and Trentino. www.stairwaystoheaven.it

» From brush to stone: the cathedral precinct of Bressanone [D3] with its cloister and several chapels is South Tyrol’s largest medieval church complex. The Romanesque monastery church of San Candido/Innichen [H3] has survived almost entirely in its original state. www.innichen.info The portals of Tyrol Castle’s [C3] great hall and chapel are among the most remarkable works of Romanesque stone masonry in the entire Alpine area. www.casteltirolo.it

Unique in Naturno: the fresco mystery of the Prokulus Kirche church is unresolved

Eminences | 73

Mountain liftsElectrical alpenglow

Fact Box:» A cable car still connects Bolzano with the summer holiday resort of

Colle [C5]. A gondola belonging to the first generation can be seen at the top terminal. Information on all three cable cars from Bolzano up to its home mountains available from www.bolzano-bozen.it

» Information on South Tyrol’s cable car pioneers can be obtained from the trustees of South Tyrol’s technical cultural heritage at

www.tecneum.eu» The only working historical cable railway in South Tyrol is on the Men-

dola/Mendel Mountain [B5], built in 1903. It is one of Europe’s steepest railways. www.eppan.travel/en/highlights/sights

It seemed impossible to catch up with Switzerland, where the mountains had been subjugated by all kinds of transport. And then the unexpected happened. On 29 June 1908 the cable car going up to Colle Mountain from Bolzano entered service, the world’s first passenger aerial cable car system, a month before the Swiss Wetterhorn cable car opened. This pioneering enter-prise was born of necessity. Financier Josef Staffler built a hotel in the hamlet of Colle high above Bolzano and began await-ing guests. A road up the mountain was out of the question, and Staffler couldn’t afford a cable railway. The only alterna-tive was the air. At the time, South Tyrol’s cable car expert was Luis Zuegg. In 1912 the industrialist planned the cable car from Lana up to San Vigilio Mountain, while during the First World War he built cable cars to supply soldiers, including the one on the Stelvio Pass. When the materials became scarce he taut-ened the fixed cable and had the new system patented as the Bleichert-Zuegg-System. By 1940 the companies Zuegg and Bleichert had built 35 aerial cable car systems in Europe, the USA and South Africa. Today 377 lift systems are in operation in South Tyrol. The South Tyrolean company Leitner is involved in the development of new cable car systems worldwide.

World record: the first aerial passenger cable car on Bolzano’s Kohlern Mountain entered service in 1908

74

Simplicity is luxury. Matteo Thun, an architect and designer who was born and raised in Bolzano, has tried his hand at all kinds of forms. With Ettore Sottsass he founded the Memphis design movement setting new benchmarks for the interplay of shapes during the 1980s. He was the creative director of Swatch, entered New York’s Hall of Fame in 2004 and is now one of the world’s top designers and architects. Matteo Thun demands the prohibition of inappropriate encroachments on the landscape. In architectural terms this means building in harmony with nature. Thun’s projects in the Alps illustrate this principle. Thun captures the soul of the place, asks himself how large a structure may be in proportion with its surround-ings and in his answers he considers elements such as trees and rock faces. Three hotels in South Tyrol bear Thun’s signa-ture: vigilius mountain resort above Lana in the Adige Valley in the form of a horizontal tree, the Pergola Residence near Merano, which nestles symbiotically among vineyards, and the Merano thermal baths complex, known as the Terme Merano, where he had the wood and stone treated to look as though water had smoothened their surfaces through ages of attrition. Thun’s luxury is the art of renouncing, of simplicity. It seems the only thing he can’t renounce is wellbeing.

Matteo ThunThe consummate designer

Fact Box:» Information about Matteo Thun at www.matteothun.com» vigilius mountain resort near Lana [B3] at www.vigilius.it» Pergola Residence in Lagundo/Algund [B3] at www.pergola-residence.it» Matteo Thun designed the interiors of the Terme Merano and its hotel

[C3]. www.hoteltermemerano.it» Matteo Thun’s Viewing Platform, a spectacular outlook point in the

Gardens of Trauttmansdorff Castle [C3], overlooking Merano. www.trauttmansdorff.it

76

Fact Box:» General information at www.suedtirol.info/sustainability» ClimateHouse certification system for energy-efficient construc-

tion, www.klimahaus.it» Dobbiaco District Heating Plant, www.fti.bz» To book an Enertour visit, please go to www.enertour.bz.it

Suggested Reading:» South Tyrol’s province government inter alia (Ed.),

KlimaLand Südtirol, KVB Publishing House, Munich 2012

Salewa, which makes sporting goods for mountaineering, is housed in a building designed by architect Cino Zucchi (Milan) that has been honoured with the 2012 ClimateHouse Award

Eminences | 77

For South Tyrol’s electric power of the future, nature is the gen-erator. Sun, forest, water: these are the energy sources that will power the province in the most sustainable way. South Tyrol’s 300 sunny days a year represent enviable solar potential in the Alps; 42% of the land area is covered by forest, providing mate-rial for the timber industry and biomass district heating plants. Surrounded by mountains, water flows out of every “pore”: 963 hydropower plants produce nearly double the electricity that the province consumes, and the surplus is exported.Currently, 40% of South Tyrol’s energy needs are being met by renewable energy. The province has thus reached a peak value in comparison with other regions in the Alps. The climate strat-egy of the Province of South Tyrol is cranking up the goals even more: by 2020, 75% of the energy demand for electricity, heat and transport will be met by renewable energy sources; by 2050, more than 90%. The vision also involves saving energy in the future through energy-efficient construction, comprehen-sive redevelopment concepts for buildings, and the responsi-ble use of the resources.Green, green, and more green: three projects set a precedent. The ClimateHouse certification system, which was developed in South Tyrol, promotes energy-efficient construction and renovations with high-level comfort. The programme is on course for success throughout Italy. An annual ClimateHouse Award has even been presented for ten years now. In 2012, awards went to Salewa, located in the industrial zone of Bolza-no, and Uridl-Hof Farm the Gardena Valley, among others. From single building to village community: the community of Dobbiaco, which has 3,300 inhabitants and is located in the Pusteria Valley, uses only energy from renewable sources: hy-dropower, a district heating plant, and from various photovol-taic and solar thermal energy systems. A visitor’s display at the municipality’s district heating plant traces the process of gen-erating electricity out of biomass. A first-hand experience of South Tyrol’s model projects is made possible through Ener-tour: the project offers field visits with guided tours of show-cases for innovative living and power generation. It’s high volt-age, of course.

Naturally green Energy efficiency & renewable energy

78

Farmstead in the Tures and Aurina valleys: 65% of South Tyrol’s farmsteads are located above 4,900 feet in elevation

Tradition | 79

The art of self-preservationSince time immemorial modernity has influenced life in the valley,

while at higher elevations, people have held on to their traditional way of life. Knowledge about nature and everyday tradition there is written in people’s DNA.