Sikundur Monitoring Post Annual Report for 2014 - PanEco · the Gunung Leuser National Park (est....

Transcript of Sikundur Monitoring Post Annual Report for 2014 - PanEco · the Gunung Leuser National Park (est....

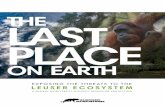

Sikundur Monitoring Post

Annual Report for 2014

2015

SUMATRAN ORANGUTAN CONSERVATION PROGRAMME

1

Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1

II. Climatological & Phenological Monitoring .................................................................................. 4

III. Habitat Monitoring ............................................................................................................................ 6

IV. Orangutan Project .......................................................................................................................... 10

V. Camera Trapping ............................................................................................................................. 16

VI. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Technology .......................................................................... 19

VII. Student Projects ............................................................................................................................ 22

-Habitat Structure ............................................................................................................................... 23

-Orangutan/Primate Vocalizations ................................................................................................... 23

-Gibbon, Siamang, and Leaf Monkey Surveys ............................................................................... 25

-Orangutan Nest Surveys.................................................................................................................. 26

VIII. Coming Up In 2015-2016 ............................................................................................................ 27

IX. References Cited ............................................................................................................................ 29

X. How to Get Involved ....................................................................................................................... 32

2

I. Introduction

Throughout their range, Sumatran orangutans are threatened by two often related

factors, habitat loss and poaching/hunting. Deforestation in Sumatra, a product of

ongoing human extractive industries (e.g., development of infrastructure, expansion of

large-scale agriculture, logging concessions, mining, and small-scale localized

encroachment), is primarily attributed to inadequate cross-sectorial land use planning,

desire for short-term economic growth, and a lack of environmental law enforcement

(Wich et al. 2011a). Most worrisome is that Sumatra’s lowland and swamp forests,

areas known to house the highest densities of orangutans (Wich et al. 2008), also have

the highest rates of deforestation (Laumonier et al. 2010; Margono et al. 2012). While

more difficult to quantify (i.e., relative to forest loss), poaching/hunting is an additional

threat to the survival of Sumatran orangutans, and is largely associated with access to

forested areas, a byproduct of deforestation/habitat fragmentation and population

growth (Wich et al. 2011a).

Interestingly, virtually all long-term monitoring studies of Sumatran orangutans, and

indeed all data in recent population viability analyses of the species (Marshall et al.

2009), have utilized ‘high-density’ orangutan populations situated in primary peat-

swamp forest (Suaq Balimbing, Aceh Province) and primary lowland rainforest

(Ketambe, Aceh Province). These two sites are regarded as “prime habitats” for

Sumatran orangutans (Husson et al. 2009) and historically have suffered relatively

lower levels of human disturbance. Accordingly, we lack knowledge of Sumatran

orangutans in more degraded landscapes, and thus also lack a complete grasp of their

behavioral, demographic, ecological, and physiological variability, factors vital to

understanding their future population viability (Marshall et al. 2009).

The Sikundur Monitoring Post is located in the Langkat District of North Sumatra

Province, within the Gunung Leuser National Park and larger Leuser Ecosystem

National Strategic Area [Fig. 1]. It consists of previously logged lowland dipterocarp

tropical rainforest, and even so, is one of the few remaining lowland areas that still

maintains suitable forest habitat for the Critically Endangered Sumatran orangutan. As

such, the importance of the Sikundur Monitoring Post and its relevance to long-term

Sumatran orangutan conservation must be underscored. The Sumatran Orangutan

Conservation Programme (SOCP) started orangutan and habitat monitoring at Sikundur

in the second half of 2012 and is now in its third year of operation there.

Building off of 2013’s successes, the 2014 field season at Sikundur was full of a lot of

new developments and a tremendous amount of progress. These include an increase in

orangutan follows and some new focal individuals, additions to the long-term

3

climatological and phenological datasets, more intensified habitat monitoring efforts,

camera trapping, comparative drone nest surveys, and three new student projects. The

purpose of this short report will be to highlight some of these activities and emphasize

Sikundur’s importance to orangutan conservation and also the conservation of

Sumatra’s unique biodiversity.

Fig. 1. The location of the Sikundur Monitoring Post in relation to the Gunung

Leuser National Park and the Leuser Ecosystem National Strategic Area.

4

II. Climatological & Phenological Monitoring

At the Sikundur Monitoring Post, the average monthly rainfall during August 2013 –

February 2015 was 256.4 mm, with a monthly range of 12.4-535.4 mm [Fig. 2]. During

2014, the only complete year of observation, the total amount of rainfall was 3,042.8

mm. In general, higher levels of rainfall occurred during April-May, September-October,

and December, whereas low levels of rainfall occurred during January-March, June-

July, and November. Both February and March of 2013 were found to be below 100

mm, indicating extreme lows in rainfall.

Fig. 2. The average rainfall and temperature for the Sikundur Monitoring Post from August

2013 – February 2015.

Average monthly temperatures from within the field station were 27.3° C, with a monthly

range of 26.1-29.2° C [Fig. 2]. During the observation period, temperature highs were

recorded for the months February-July, whereas temperature lows were recorded for

the months of October-January.

5

Fig. 3. The average rainfall and percent fruit productivity for the Sikundur Monitoring Post

from June 2013 – February 2015.

The average percent of lianas and trees (>10 cm diameter at breast height) that were

bearing fruit in our 20 phenological plots was 3.6% for the period of June 2013 –

February 2015, with a range of 0.3-13.0% [Fig. 3]. High fruiting values were observed

during May and July-September, with low fruiting values being observed during

December-April. Extreme high fruiting values were observed for June-October 2014.

We are hesitant to suggest that a masting event occurred during this period, given that

the phenology dataset included in this study encompasses only 21 months; however,

the range of fruiting values indicates that there is a considerable level of fruiting

variability at the Sikundur study site.

It is interesting to note that the average fruiting score for Sikundur (3.6%) falls within the

percent fruiting score range of a number of Bornean field sites (3.0-6.8%); however

conversely, it is well outside the range of percent fruiting scores of two Sumatran (6.9-

30.57%) sites, Ketambe and Suaq Balimbing (Wich et al. 2011b). Thus, the Sikundur

Monitoring Post has lower fruit productivity than that of previously studied Sumatran

orangutan field sites, indicating that Sumatra is far less homogeneous than currently

thought and that a portion of remaining orangutan habitat in Sumatra is far less

productive than previously thought.

6

III. Habitat Monitoring

The Sikundur area, previously the Sikundur Reserve (est. 1938) prior to the formation of

the Gunung Leuser National Park (est. 1980) was selectively logged starting in the late

1960’s, which continued and progressively intensified in some areas until the 1980’s

(Cribb, 1988; Wind, 1996). Following the establishment of the Gunung Leuser National

Park, logging in the Sikundur area continued primarily at the park boarder. Currently,

illegal logging and in some cases complete land clearing are still present near the

southeastern boundary of the Sikundur Monitoring Post at the Gunung Leuser National

Park border, in addition to more generalized illegal human extractive activities (e.g., bird

trapping, damar resin extraction, and fishing), which will be discussed in more detail

below. Our analysis of forest disturbance/loss in the Langkat District from 2013-2014,

using monthly FORMA forest loss data downloaded freely from the Global Forest Watch

website (www.globalforestwatch.org; Hammer et al. 2013; Hansen et al. 2013),

discovered 409 forest disturbance ‘hotspots’ (resolution 500m x 500m) in the Langkat

District during this period [Fig. 4]. A total of 94 of these 409 ‘hotspots’ (23% of all

‘hotspots’ within the Langkat District) are within 10 kilometers of the Sikundur Monitoring

Post and also within the Leuser Ecosystem National Strategic Area. These disturbance

‘hotspots’ have allowed us to focus our habitat monitoring efforts on key areas of

deforestation within the Gunung Leuser National Park and the Leuser Ecosystem

National Strategic Area and provide a starting point for more detailed monitoring.

For example, last year in May of 2014, using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), we

surveyed a large area of deforestation <1.5 kilometers from SOCP’s camp within the

Sikundur Monitoring Post. This aerial survey allowed for the production of a highly

detailed photomosaic showing the level of deforestation [Fig. 5]. A subsequent field

report was successful in prompting a patrol team from the Gunung Leuser National Park

to come and remove the illegal encroachers. Unfortunately, the illegal encroachers have

again entered the research station during the end of 2014 and beginning of 2015 and

have again started land clearing within the Gunung Leuser National Park [Fig. 6]. The

proper authorities have already been notified; however, a patrol team has not yet come

to take action. This unfortunate situation serves to highlight that early detection and

immediate responses from the proper authorities can be implemented to reduce illegal

activities, but that adequate follow-up activities are required to maintain any of these

positive achievements. Our observations also indicate that the threat of deforestation to

orangutans is ongoing and that in some cases, protected areas will likely not be enough

to preserve orangutan habitat, if the proper authorities are unable to adequately enforce

current laws.

7

Fig. 4. Forest loss in the Langkat District. The spatial data was collected from the

Global Forest Watch website (www.globalforestwatch.org; Hammer et al. 2013;

Hansen et al. 2013). The black dashed circle highlights the area nearest the

Sikundur Monitoring Post. Note the blue and green squares within the circle,

which are FORMA deforestation alerts from 2013 and 2014.

8

Fig. 5. Recent forest loss in the Sikundur Monitoring Post. A) Forest

loss in relation the Sikundur Monitoring Post. The spatial data was

collected from the Global Forest Watch website

(www.globalforestwatch.org; Hammer et al. 2013; Hansen et al.

2013). B) UAV photographs showing cleared land from May 2014.

A.

B.

9

Fig. 6. Photographs showing illegal encroachment within both the Gunung Leuser

National Park and the Leuser Ecosystem National Strategic Area from 2014. Note that

the area is also within the grid of the Sikundur Monitoring Post. Photographs by James

Askew.

10

IV. Orangutan Project

The 2014 field season was tremendously successful and follows increased from 111

follow days in 2013 to 359 follow days in 2014 [Table 1]. In addition, there were three

new adult orangutans (one female and two males) that were contacted and followed in

2014, plus one of the resident females (Madeline) gave birth in June of 2014. This has

brought our total of habituated animals to 15, including 5 adult females, 6 adult males,

and 4 infants.

Results from all orangutan follows >3 hours duration suggest that on average (n=21

months), adult orangutans at Sikundur were found to feed 48.5% of the time [Fig. 7],

followed by rest ( x =31.1%), travel ( x =18.3%), and other ( x =2.2%). During periods of

fruit scarcity (n=10 months), adult orangutans were observed to feed 55.1% of the time,

followed by rest ( x =26.0%), travel ( x =17.0%), and other ( x =1.9%). Conversely

during periods of fruit abundance (n=8 months), adult orangutans were observed to feed

40.9% of the time, followed by rest ( x =35.8%), travel ( x =19.8%), and other ( x

=2.9%). Thus, the primary differences were more feeding during fruit scarce periods,

with greater emphasis on all other behaviors during fruit abundant periods.

During the observation period, adult orangutans were observed to feed primarily on fruit

( x =62.0%), followed by leaves ( x =14.9%), bark ( x =9.7%), piths/stems ( x =5.4%),

invertebrates ( x =4.8%), flowers ( x =2.7%), and other ( x =0.6%) [Fig. 8]. When fruit

was scarce, adult orangutans were observed to feed on fruit ( x =47.2%), leaves ( x

=18.2%), bark ( x =16.7%), piths/stems ( x =7.6%), invertebrates ( x =5.9%), flowers ( x

=4.1%), and other ( x =0.3%). When fruit was abundant, adult orangutans were

observed to feed on fruit ( x =81.4%), leaves ( x =7.4%), piths/stems ( x =4.2%),

invertebrates ( x =3.4%), bark ( x =1.8%), flowers ( x =0.9%), and other ( x =0.9%). The

primary differences are the significant amount of fruit feeding during fruit abundant

periods and the significant amount of feeding on lower quality food resources (e.g., bark

and leaves) during fruit scarce periods.

These differences in activity budgets are likely related a greater handling time needed

with lower quality resources in the fruit scarce months and the emphasis on travelling to

higher quality resources during fruit abundant months, plus the energetic freedom to

utilize time for rest and social behaviors. These results are quite different from that of

previously published Sumatran orangutan populations and indicate that orangutans in

Sikundur are impacted seasonally by fruit availability. These results also suggest that

Sikundur orangutans utilize a feeding/foraging strategy that is intermediate between

Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, making the division between Bornean and

11

Sumatran orangutans more enigmatic (Morrogh-Bernard et al. 2009). Given that this is

the first study to conduct orangutan research on the eastern portion of the Bukit Barisan

Mountain Range, a known climatological barrier, these results have important

conservation implications for the remaining orangutan population in the eastern portion

of the Leuser Ecosystem National Strategic Area. This, in combination with our

analyses of fruiting seasonality, highlights that we are just starting to understand

Sumatran orangutan population variability and that these and future results will be vital

to our current and future viability analyses and conservation strategies.

12

Nam

eA

ge C

lass

Sex

Jan

Feb

Mar

Ap

rM

ayJu

nJu

lA

ug

Sep

Oct

No

vD

ec

An

toA

du

ltM

ale

--

--

--

--

--

--

Be

nd

ot

Ad

ult

Mal

e-

--

--

1-

--

--

-

Irm

a +

off

spri

ng

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

--

--

--

--

-5

--

Irva

n (

Irm

a’s

off

spri

ng)

Infa

nt

Mal

e-

--

--

--

--

5-

-

Jam

es

Ad

ult

Mal

e-

--

--

--

--

--

-

Ku

nd

ur

(Be

nd

ot

Ke

cil)

Ad

ult

Mal

e2

--

--

--

--

--

-

Mad

eli

ne

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

--

10-

4-

5-

--

53

Mat

Pan

gko

rA

du

ltM

ale

--

--

--

5-

--

--

Om

pu

ng

Ad

ult

Mal

e-

-5

1-

2-

--

--

-

Rak

el

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

--

--

--

--

--

--

Sib

oy

- (S

uci

's o

ffsp

rin

g)In

fan

t?

--

64

5-

5-

--

--

Suci

+ o

ffsp

rin

gA

du

ltFe

mal

e-

-6

45

-5

--

--

-

Yan

ti +

off

spri

ng

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

--

-1

6-

--

2-

--

Yen

i (Ya

nti

's o

ffsp

rin

g)In

fan

t?

--

-1

6-

--

2-

--

Tota

l-

-2

027

1126

320

04

105

3

Nam

eA

ge C

lass

Sex

Jan

Feb

Mar

Ap

rM

ayJu

nJu

lA

ug

Sep

Oct

No

vD

ec

An

toA

du

ltM

ale

--

--

-3

--

2-

--

Be

nd

ot

Ad

ult

Mal

e4

1-

-10

--

--

--

-

Irm

a +

off

spri

ng

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

108

-8

22

2-

5-

--

Irva

n (

Irm

a’s

off

spri

ng)

Infa

nt

Mal

e10

8-

72

2-

-5

--

-

Jam

es

Ad

ult

Mal

e-

--

--

31

--

--

-

Ku

nd

ur

(Be

nd

ot

Ke

cil)

Ad

ult

Mal

e-

--

--

74

3-

--

-

Mad

eli

ne

+ o

ffsp

rin

gA

du

ltFe

mal

e-

61

111

9-

2-

75

5

Mal

ala

(Mad

eli

ne

's o

ffsp

rin

g)In

fan

t?

--

--

-9

--

-6

55

Mat

Pan

gko

rA

du

ltM

ale

--

--

--

--

--

--

Om

pu

ng

Ad

ult

Mal

e-

-10

5-

-4

-1

810

2

Rak

el

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

--

--

--

--

--

6-

Sib

oy

- (S

uci

's o

ffsp

rin

g)In

fan

t?

69

55

47

95

31

2-

Suci

+ o

ffsp

rin

gA

du

ltFe

mal

e6

95

54

79

53

12

-

Yan

ti +

off

spri

ng

Ad

ult

Fem

ale

23

-3

-1

--

1-

--

Yen

i (Ya

nti

's o

ffsp

rin

g)In

fan

t?

23

-3

-1

--

1-

--

Tota

l-

-40

4721

4723

5129

1521

2330

12

20

14

20

13

Tab

le 1

. Fo

cal o

ran

guta

ns

at S

iku

nd

ur

and

th

eir

20

13

-20

14

mo

nth

ly f

oll

ow

sch

ed

ule

s.

13

Fig. 7. Activity budgets of adult orangutans at the Sikundur Monitoring Post, comparing

between two seasonal periods.

Fig. 8. Diet of adult orangutans at the Sikundur Monitoring Post, comparing between two

seasonal periods.

14

Fig. 9. Photographs of two adult female orangutans at Sikundur. A) Madeline with Malala

her new infant and Anto (adult male) sitting nearby; B) Irma watching her infant Irfan play.

Photographs courtesy of James Askew.

A)

B)

15

Fig. 10. Photographs of two adult male orangutans at Sikundur. A) Ompung feeding on

termites; B Bendot Besar feeding on fruits. Photographs courtesy of James Askew.

A)

B)

16

V. Camera Trapping

Via a small crowd funding grant which was received through experiment.com, SOCP’s

Biodiversity Monitoring Unit, along with two graduate student researchers James Askew

(University of Southern California) and John Abernethy (Liverpool John Moores

University) developed a site wide camera trap survey of the Sikundur Monitoring Post.

Using a randomized grid of 30 camera traps, the survey sought to analyze the

distribution of animal species across the three main habitat types (i.e., alluvial, hill, and

plain forest) at the Sikundur Monitoring Post. The results from 2,700 camera traps

nights has yielded a list of at least 31 animal species from 19 families, and three classes

[Table 2]. From this list, eight are identified as Vulnerable (VU) by the IUCN, with three

being identified as Critically Endangered (CR). The Critically Endangered species

include the Sumatran elephant, orangutan, and tiger [Fig. 11-13].

The presence of orangutans on the camera traps is quite interesting, as Sumatran

orangutans do not commonly come to the ground, being characterized as almost strictly

arboreal (van Schaik et al. 2009). Nevertheless, in addition to the camera trap photos,

we have also documented ground use by a number of adult orangutans (both female

and male) during full day follows, some of which have foraged on the ground for a

couple of hours. These observations are being looked at in greater detail, as this is a

trait more common in some Bornean orangutan populations and thought to be at least

partially related to the lack of tigers in Borneo (van Schaik et al. 2009; Ancrenaz et al.

2014).

Unfortunately, one of the most photographed species was humans. From the

photographs, it was clear that their primary activities in the forest include bird trapping,

damar resin extraction, fishing, and illegal logging. This also highlights the potential

importance of camera traps in habitat protection.

17

Class Family Species Common Name IUCN Status

Aves Bucerotidae Berenicornis cornatus White-crowned hornbill NT

Aves Bucerotidae - - -

Mammalia Cercopithecidae Macaca fascicularis Long-tailed Macaque LC

Mammalia Cercopithecidae Macaca nemestrina Pig-tailed Macaque VU

Mammalia Cercopithecidae Presbytis thomasi Thomas's Leaf Monkey VU

Mammalia Cercopithecidae - - -

Mammalia Cervidae Muntiacus muntjac Red Muntjac DD

Mammalia Cervidae Rusa (Cervus) unicolor Sambar Deer VU

Mammalia Cervidae - - -

Aves Columbidae Chalcophaps indica Emerald Dove LC

Aves Columbidae - - -

Mammalia Elephantidae Elephas maximus sumatranus Asian Elephant CR

Mammalia Elephantidae - - -

Mammalia Erinaceidae Echinosorex gymnurus Moonrat DD

Mammalia Erinaceidae - - -

Mammalia Felidae Catopuma temminck ii Asiatic Golden Cat NT

Mammalia Felidae Neofelis diardi Sunda Clouded Leopard VU

Mammalia Felidae Pardofelis marmorata Marbled Cat VU

Mammalia Felidae Felis bengalensis Leopard Cat DD

Mammalia Felidae Panthera tigris sumatrae Sumatran Tiger CR

Mammalia Felidae - - -

Mammalia Herpestidae Herpestes brachyurus Short-tailed Mongoose LC

Mammalia Herpestidae - - -

Mammalia Hominidae Homo sapiens Human LC

Mammalia Hominidae - - -

Mammalia Hystricidae Hystrix sumatrae Sumatran Porcupine LC

Mammalia Hystricidae - - -

Mammalia Mustelidae Martes flavigula Yellow-Throated Martin LC

Mammalia Mustelidae - - -

Aves Phasianidae Rollulus rouloul Crested Partridge NT

Aves Phasianidae - - -

Mammalia Pongidae Pongo abelii Sumatran Orangutan CR

Mammalia Pongidae - - -

Reptilia Pythonidae Python reticulatus Reticulated Python NE

Reptilia Pythonidae - - -

Mammalia Sciuridae Ratufa bicolor Black Giant Squirrel NT

Mammalia Sciuridae Sundasciurus hippurus Horse-tailed Squirrel NT

Mammalia Sciuridae - - -

Mammalia Suidae Sus scrofa Wild Boar LC

Mammalia Suidae - - -

Mammalia Tragulidae Tragulus javanicus Lesser Mouse Deer DD

Mammalia Tragulidae Tragulus napu Greater Oriental Chevrotain LC

Mammalia Tragulidae - - -

Mammalia Ursidae Helarctos malayanus Sun Bear VU

Mammalia Ursidae - - -

Mammalia Viverridae Arctictis binturong Binturong VU

Mammalia Viverridae Arctogalidia trivirgata Small-toothed Palm Civet LC

Mammalia Viverridae Hemigalus derbyanus Banded Civet VU

Mammalia Viverridae Paradoxurus hermaphroditus Common Palm Civet LC

Mammalia Viverridae - - -

Total 19 31 - -

Table 2. Animal Species Detected on Camera Traps in the Sikundur Monitoring Post

18

Fig. 11. The Critically Endangered Sumatran elephant from a camera trap photo. Photo by SOCP.

Fig. 12. The Critically Endangered Sumatran orangutan (Ompung) from a camera trap photo. Photo by

Sonny Royal/SOCP.

19

Fig. 13. The Critically Endangered Sumatran tiger from a camera trap photo. Photo by SOCP.

VI. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Technology

In December – January of 2014, SOCP’s UAV team worked alongside SOCP’s

Sikundur team to undertake a unique orangutan nest survey, which attempts to

compare two survey methods, aerial UAV nest surveys and ground-based nest surveys

[Fig. 14-15]. The monitoring project, which is jointly undertaken by both SOCP and

Conservation Drones seeks to develop the UAV survey methodology, so that orangutan

nest surveys can be conducted more efficiently and over larger landscapes than is

currently possible for ground-based surveys. Fig. 14 shows an example plot mosaic that

is 1000 x 50 meters. In theory, an algorithm would be utilized to detect orangutan nests

(e.g., the nests from a UAV photo shown in Fig. 14) within a given transect mosaic and

then orangutan densities would be calculated from these figures and a correction factor

for non-detected nests. The results are currently being analyzed.

During the same period as the UAV nest survey, SOCP was also able to create a

detailed mosaic of the entire Sikundur station (ca. 8 km2) and this will serve as the basis

for a number of future analyses, including forest structure and orangutan travel paths

[Fig. 15-16]. We also note that when compared with Fig. 5, the areas that were cleared

in May 2014 were already beginning to grow back, highlighting the capability of UAV

technology in detecting and monitoring critical forest habitats.

20

1000 meters

50 meters

Fig. 14. An example of the aerial nest survey

undertaken by SOCP at the Sikundur Monitoring Post

at the end of 2014 (left). Ten transects, each 1000 x

50 meters, were surveyed by both the UAV’s and

SOCP staff. Comparisons will be made to see if it is

possible to utilize UAV’s to do orangutan surveys,

something that would be highly cost effective and

would allow for greater aerial coverage. The

photograph to the top is an example of two

orangutan nests that were detected using UAV’s.

Both images are from Conservation Drones

(conservationdrones.org), via Dr. Serge Wich and Dr.

Lian Pin Koh.

Nest

21

Fig. 15. Photographs showing SOCP’s Sikundur team (top) and a member of

SOCP’s UAV team (bottom) conducting the ground-based and aerial surveys,

respectively.

22

Fig. 16. A photomosaic of the entire Sikundur Monitoring Post which was created by SOCP using

multiple UAV flights at the end of 2014 and beginning of 2015. Note that a few of the areas that had

been encroached upon (outlined in red) in May 2014 have already started to grow back. See Fig, 5 for

comparison. The yellow lines are the station’s grid system and the purple line is the border of the

Gunung Leuser National Park. The photomosaic is courtesy of Graham Usher, SOCP’s UAV

specialist.

VII. Student Projects

SOCP has been lucky enough to establish collaborations with the Bournemouth

University (UK), Liverpool John Moores University (UK), and University of Southern

California (USA). These new collaborations have already allowed for the development

of some very interesting projects, which are currently being undertaken by graduate

student from the aforementioned universities. The focus for 2014-2015 has been a

detailed look at habitat structure, primate surveys, and primate vocalizations.

23

-Habitat Structure

Two Master’s students from Bournemouth University (Helen Slater & Rosanna

Consiglio) and one PhD student from Liverpool John Moores University (John

Abernethy), guided by Drs. Amanda Korstjens, Ross Hill, and Serge Wich have now

started to undertake a detailed look at habitat structure in the Sikundur Monitoring Post.

For this particular project, 10 transects from each of three main micro-habitat types

(alluvial, plain, and hill forest) were surveyed by the three graduate students [Fig. 17].

During the surveys, the students collected various habitat structural data, which will

eventually be linked to primate densities, primate behavior, and will also serve as an

important component in future UAV analysis.

Fig. 17. A map highlighting the 30 transects utilized during surveys of habitat structure.

-Orangutan/Primate Vocalizations

Graduate PhD student James Askew from the University of Southern California,

directed by Drs. Craig Stanford and Roberto Delgado, is seeking to better understand

orangutan social behavior and reproductive strategies, with an emphasis on how

24

orangutans respond to male long calls. For his observations, Mr. Askew utilizes long call

playbacks and then evaluates how focal orangutans respond to the playback

experiments [Fig. 18]. This project proves to give us a better understanding of

Sumatran orangutan social behavior, as few researchers have attempted a study like

this on Sumatran orangutans.

Fig. 18. Graduate researcher from University of Southern California, James Askew, undertakes

a playback experiment at the Sikundur Monitoring Post. Photo courtesy of John Abernethy.

In addition to the playback experiments, Mr. Askew is also attempting to record primate

vocalizations, in order to better understand their function and also survey some of the

more unique primates within the area. For instance, white-handed gibbons

(Endangered), siamangs (Endangered), and Thomas’ leaf monkeys (Vulnerable)

regularly vocalize, most often nearest sunrise. Using audio recorders that are fitted with

a real time clock and GPS unit [Fig. 19], Mr. Askew will attempt to survey the three

aforementioned primates and then using spatial capture-recapture methods estimate

their local densities. This project will also serve a comparative dataset for the fixed

count vocal surveys that Helen Slater and Rosanna Consiglio will conduct on the same

three species (see below).

25

A detailed look at Mr. Askew’s research and his journey through Indonesia can be

accessed via his Scientific American Expeditions blog –

(blogs.scientificamerican.com/expeditions).

Fig. 19. Two of SOCP’s assistants help to setup one of the audio reorders that were used during

audio surveys of gibbons, siamangs, and Thomas’ leaf monkeys. Photo courtesy of James

Askew.

-Gibbon, Siamang, and Leaf Monkey Surveys

In addition to their analyses of habitat structure at Sikundur, Helen Slater and Rosanna

Consiglio are also interested in evaluating the densities of three key primate species,

the white-handed gibbon (Endangered), siamang (Endangered), and Thomas’ Leaf

Monkey (Vulnerable). Using the fixed point call count methodology established by

Brockelman & Ali (1987) and Brockelman & Srikosamatara (1993), Ms. Slater and Ms.

Consiglio will conduct surveys at three listening arrays, each comprised of three

listening posts [Fig. 20]. The three arrays were set up in each of the three micro-habitat

types. Data recorded for each listening post includes the time of the group call, the

species, the compass bearing, and the estimated distance. Via triangulation, these data

can be used to estimate primate group densities and these densities will eventually be

evaluated relative to forest structure. These data will also serve a comparative dataset

for the audio data discussed above. This will be the first time that a comparison of these

survey methods will be undertaken for these primate species.

26

Fig. 20. A map of the three fixed point vocal arrays that will be surveyed by Helen Slater and Rosanna

Consiglio, in their analyses of gibbon, siamang, and Thomas’ leaf monkey densities.

-Orangutan Nest Surveys

John Abernethy, a PhD student from Liverpool John Moores who is directed by Dr.

Serge Wich, is undertaking a detailed orangutan nest survey which will allow him to

calculate orangutan density estimates, and he will be trying to link the survey results to

that of habitat structure [Fig. 21]. Orangutan nest surveys rely on the fact that

orangutans construct nests daily, which are used at night and also sometimes during

the day for resting (van Schaik et al. 1995). Using nest counts instead of live encounters

with orangutans is often preferred due to the low density of orangutans, making density

estimates based on live encounters a very time consuming exercise. It also allows

researchers to systematically do repeat monitoring of a given area. This will be the first

time that the Sikundur area will be surveyed since the first surveys in early 2000s (Knop

et al. 2004).

As the Sikundur area was previously logged, Mr. Abernethey’s analyses are a key

component to understanding the behavioral strategies of orangutan populations in

27

Sumatra’s degraded forest areas. Furthermore, given that the majority of lowland areas

housing orangutans in Sumatra are either completely deforested or highly degraded,

this project is highly important to current and future conservation strategies of Sumatran

orangutans.

Fig. 21. A photophragh of John Abernethy and a few of SOCP’s assistants undertaking orangutan nest

surveys.

VIII. Coming Up In 2015-2016

Given the successes of both the 2013 and 2014 field seasons, we are very much

looking forward to the 2015 field season. In addition to SOCP’s regular habitat and

orangutan monitoring activities, there are a number of new student projects from both

Bournemouth University and Liverpool John Moores University that will be started within

2015. Many of these will have a focus on local habitat structure and will attempt to

utilize the new technologies (e.g., UAVs) that we have been trying to develop over the

past couple of years. One project in particular is a detailed look at how canopy

28

height/structure affects primate behavioral strategies, which is being conducted with the

help of Drs. Ross Hill, Amanda Korstjens, and Serge Wich. An example of this is shown

below [Fig. 22], which highlights the height of the canopy in relation to orangutan travel

paths. The preliminary findings seem to suggest that orangutans at Sikundur utilize

higher canopy areas more frequently than would be predicted by chance alone.

Fig. 22. A map of canopy height from the Sikundur monitoring post, with a

layer of orangutan travel paths on top. The shapefile is courtesy of Dr.

Ross Hill and Serge Wich.

29

Given that the Langkat District is one of the most deforested areas in the Leuser

Ecosystem National Strategic Area and also one of the areas with the highest

incidences of human-orangutan conflict and poaching, the SOCP also seeks to develop

a greater capacity for conservation education, conflict mitigation, and local capacity

building in the Langkat area over the next couple of years. Our aims are to: 1) conduct

local village/school visits with relevant educational presentations; 2) enhance our ability

to help mitigate conflicts associated with Sumatran orangutans; and 3) support local

Indonesian students, as they pursue university degrees relevant to orangutan

behavioral ecology and conservation. The development of these three key activities is

set to begin in the second-half of 2015.

Lastly, with all of the projects that have been undertaken during 2013-2014, we at

SOCP are already working diligently on a number of key publications that will help to get

the word out about this unique lowland Sumatran rainforest habitat. We thank you for

your continued support and ask that you keep your eye out for these exciting future

publications.

IX. References Cited

Ancrenaz et al. 2014. Coming down from the trees: Is terrestrial activity in Bornean

orangutans natural or disturbance driven? Scientific Reports, 4(4924), 1-5. DOI:

10.1038/srep04024.

Brockelman WY, Ali R. 1987. Methods of surveying and sampling forest primate

populations. In: Marsh CW and Mittermeier RA (eds.), Primate Conservation in the

Tropical Rain Forest, Alan R Liss, New York, pp 23-62.

Brockelman WY, Srikosamatara S. 1993. Estimation of Density of Gibbon Groups by

Use of Loud Songs. American Journal of Primatology, 29, 93-108.

Cribb R. 1988. The politics of environmental protection in Indonesia. Centre of

Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Hammer et al. 2013. FORMA Alerts. World Resources Institute and Center for Global

Development. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on 1 December 2014.

www.globalforestwatch .org.

30

Hansen et al. 2013. High-resolution global maps of 21st-Century forest cover change.

Science, 342, 850-853.

Husson et al. 2009. Orangutan distribution, density, abundance, and impacts of

disturbance. In: Wich SW et al. (eds.), Orangutans: Geographic variation in behavioural

ecology and conservation, Oxford University Press. Oxford, pp 77-96.

Knop et al. 2004. A comparison of orang-utan density in a logged and unlogged forest

on Sumatra. Biological Conservation, 120,183-188.

Laumonier et al. 2010. Eco-floristic sectors and deforestation threats in Sumatra:

identifying new conservation area network priorities for ecosystem-based land use

planning. Biodiversity Conservation, 19, 1153-1174

Margono et al. 2012. Mapping and monitoring deforestation and forest degradation in

Sumatra (Indonesia) using Landsat time series data sets from 1990 to 2010. Environ

Res Lett, 7, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034010.

Marshall et al. 2009. Orangutan population biology, life history, and conservation. In:

Wich SW et al. (eds.), Orangutans: Geographic variation in behavioural ecology and

conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 311-326.

Morrogh-Bernard et al. 2009. Orangtuan activity budgets and diet. In: Wich SW et al.

(eds.), Orangutans: Geographic variation in behavioural ecology and conservation.

Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 119-133.

Wich et al. 2008. Distribution and conservation status of the orang-utan (Pongo spp.) on

Borneo and Sumatra: How many remain? Oryx, 42(3), 329-339.

Wich et al. 2011a. Orangutans and the economics of sustainable forest management in

Sumatra. UNEP/GRASP/PanEco/YEL/ICRAF/GRID-Arendal, Indonesia.

Wich et al. 2011b. Forest production is higher on Sumatra than on Borneo. PLos ONE,

6(6), e21278. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021278

Wind, J. 1996. Gunung Leuser National Park: History threats, and options. In: van

Schaik C and Supriatna J (eds.), Leuser: A Sumatran Sanctuary. Yayasan Bina Sains

Hayati Indonesia, Indonesia, pp 4-27.

31

van Schaik et al. 1995. Population estimates and habitat preferences of orangutans

based on line transects of nests. In: Nadler RD et al. (eds.), The Neglected Ape.

Plenum Press, New York, pp 129-147.

van Schaik et al. 2009. Geographic variation in orangutan behavior and biology. In:

Wich SW et al. (eds.), Orangutans: Geographic variation in behavioural ecology and

conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp 351-361.

32

X. How to Get Involved

If you would like to make a donation or would like further information about our Sikundur project, please contact us: Matthew G. Nowak Director of Biodiversity Monitoring (SOCP) Email: [email protected] Dr. Ian Singleton Director SOCP Email: [email protected] Donations can also be made via Paypal online at: www.sumatranorangutan.org/research Follow all of our developments online at: www.sumatranorangutan.org

33