São Paulo, city-region: constitution and development dynamics of the São Paulo macrometropolis

-

Upload

maria-de-lourdes -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of São Paulo, city-region: constitution and development dynamics of the São Paulo macrometropolis

This article was downloaded by: ["Queen's University Libraries, Kingston"]On: 20 August 2014, At: 11:53Publisher: Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office:Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of Urban SustainableDevelopmentPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscriptioninformation:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjue20

São Paulo, city-region: constitution anddevelopment dynamics of the São PaulomacrometropolisGerardo Silva a & Maria de Lourdes Fonseca aa Universidade Federal do ABC (UFABC) , BrazilPublished online: 04 Jun 2013.

To cite this article: Gerardo Silva & Maria de Lourdes Fonseca (2013) São Paulo, city-region: constitutionand development dynamics of the São Paulo macrometropolis, International Journal of Urban SustainableDevelopment, 5:1, 65-76, DOI: 10.1080/19463138.2013.782707

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2013.782707

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”)contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and ourlicensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, orsuitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publicationare the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor &Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independentlyverified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for anylosses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilitieswhatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to orarising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantialor systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and usecan be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 2013Vol. 5, No. 1, 65–76, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2013.782707

São Paulo, city-region: constitution and development dynamicsof the São Paulo macrometropolis

Gerardo Silva and Maria de Lourdes Fonseca*

Universidade Federal do ABC (UFABC), Brazil

(Received 27 June 2012; final version received 5 March 2013)

This article deals with the emergence of the city-region in São Paulo (Brazil), called ‘macrometropolis’, andhighlights some of the challenges facing this new territorial or spatial configuration in terms of globalisationand governance. It also stresses the productive changes that gave rise to it and sheds light on the constituentdynamics of the macrometropolis at different scales. The article affirms that metropolitan problems canno longer be interpreted without taking into account the new determinants of the macrometropolis of SãoPaulo, which implies considering the interaction of the metropolis with other urban centres bearing social,economic and environmental singularities.

Keywords: city-region; macrometropolis; São Paulo; spatial dynamics; productive configuration; globali-sation; governance

1. Introduction

City-regions have been studied since the1980s when Los Angeles and San Francisco –California’s two largest cities and their respectiveareas of influence – became a laboratory for newforms of production and work organisation in thecontemporary world. Authors like Allen Scott andMichael Storper (1986), Manuel Castells (1989),Edward Soja (1990) and Anne Saxenian (1994),among others, recorded facts and conceptualisedthe key trends within these territories, charac-terised by the combination of high technology,knowledge production and flexible specialisation,largely inspired by Silicon Valley’s developmentand by Los Angeles’ highly dispersive urbanconfiguration. As expected, these studies began anenthralling debate in several metropolitan areasaround the world that were experiencing similar,though not necessarily analogous, trends andprocesses.

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

The renewed debate suggested by these authorspointed to an economic crisis in industrialisednations, relocation of factories to Southeast Asiaand other developing countries (such as Brazil),accompanied by the emergence of a new modelof production and organisation, characterised bythe diffusion of high-technology companies (pri-marily information technology) supported by high-density network infrastructure equipment.1 In thiscontext, the city (or the metropolis) took on anevident regional dimension by spatially integrat-ing productive processes that were traditionallyseparated by the concentrating logic of indus-trial organisation. As such, urban peripheries andnearby cities became part of new and renewedmetropolitan dynamics. As stated by Scott Allenet al., ‘[While] most metropolitan regions inthe past stood out mainly by one or maybetwo urban centres clearly defined, today’s city-regions are becoming increasingly polycentric

© 2013 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

66 G. Silva and M. de Lourdes Fonseca

or multi-grouped agglomerations’ ([1999] 2001,p. 16).

According to these authors, this occurredbecause of several factors, including the crisis ofFordism (or of economic and social developmentbased on large-scale industry), emergence of newforms of production and work organisation, thusincreasing diseconomies of agglomeration in largecities, opening of national economies to globalisedflows and territorial reconfiguration of local pro-ductive processes. Consequently, many older, tra-ditional and consolidated agglomerations experi-enced significant transformations in their ‘internal’course of development. Concomitantly, new urbangrowth centres gained value, ‘stretching and fixingthe urban fabric in a recentralised regional constel-lation of cities’ (Scott et al. [1999] 2001, p. 17).The city-region, therefore, appeared as a consistentspatial unit for understanding territorial dynamicsof contemporary capitalism.

The productive linkage between the city-regionand contemporary capitalism is also explored inBrazil by Magalhães (2008). According to theauthor, it is a reorganisation of the general formsof production that were predominantly based onthe linkage between the metropolis and the verti-cal integration of production chains, giving way tothe rise of new industries with a high technolog-ical coefficient and, generally speaking, logisticaltransformations (i.e. distribution centres, industrialparks, inland port) of industrial structure.2 As such,the morphology of the city-region, agglomeratingseveral urban and metropolitan centres, intercon-nected through powerful means of transportationand communication, established the emergence ofa new scale of territorial action for development,public policies and governance.

Although São Paulo’s case has singular andspecific characteristics, the city can be seen throughthis lens. In effect, the city of São Paulo presentlyhas 11.2 million inhabitants, but considering itsmetropolitan area, which includes 39 municipali-ties in the State of São Paulo, that number risesto 19.6 million, turning it into one of the largesturban agglomerations in the world. However, thenovelty is that despite its importance and weight

in terms of population and economic development,dynamics in recent decades show that it is increas-ingly difficult to consider it separately from otherrelatively close metropolitan areas, such as thatof Santos and Campinas and the recently createdMetropolitan Region of Vale do Paraiba,3 or with-out considering other cities such as Sorocaba andJundiai (see Box 1). In these terms, this expandedmetropolitan complex (or macrometropolis of SãoPaulo) takes on city-region characteristics, sur-passing 27 million inhabitants and concentratinga productive force equivalent to the gross domes-tic product (GDP) of Switzerland in 2010 (US$325 billion) (EMPLASA 2012).

However, the conditions of this change ofscale in the territorial development of São Pauloare unclear and require an effort to understandand interpret both the number of urban phenom-ena accompanying the expansion and the factorsexplaining it. Below we highlight some impor-tant elements of the relationship among the city,the metropolis and the macrometropolis of SãoPaulo to identify strategic issues to help scale thechallenges facing the governance of this vast newproductive territory in south-eastern Brazil.

2. São Paulo: a brief historical descriptionof urban development (of the city and themetropolis)

Throughout its 457 years of history, the city hasgone through several development stages that areworth mentioning, such as the ‘pioneer’ past4 dur-ing the colonial period; the coffee expansion cycleduring the Imperial period and, finally, the indus-trialisation process that took over the city’s devel-opment from the 1930s onwards (Santos 2005).However, it is from the 1950s that São Paulo’s paceof growth gained momentum, becoming Brazil’slargest metropolis. As shown in Table 1, whichhighlights the distribution of Brazilian industrialGDP between 1930 and 1985, there is a tremendousacceleration in the State of São Paulo’s partici-pation in the national production index until thehistoric mark of 58.1%, reached in 1970. Moreover,the posterior decline requires consideration of

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 67

Box 1. Main cities of the macrometropolis

The São Paulo Metropolitan Region occu-pies an area of 8047 km2 and encompasses39 municipalities that are home to a populationof 19.7 million inhabitants. Besides the city ofSão Paulo, this region is also composed of thecities of Guarulhos, São Bernardo do Campo,Santo Andre and Osasco. Although a process ofindustrial decentralisation has occurred in recentdecades, it still is an important industrial centrein the country, even experiencing an expansion ofindustrial activity, albeit with a reduction in thenumber of jobs in the sector. Thus, unlike otherlarge cities in developed countries, the RMSPhas not undergone a process of deindustrialisa-tion, maintaining itself as an important industrialcentre.

The Campinas Metropolitan Region con-sists of 19 municipalities, centred around thecities of Campinas, Paulinia, Sumare, SantaBarbara d’Oeste, Americana and Jaguariuna.Currently, it has 2.8 million inhabitants. It isthe second largest region in economic impor-tance, where the industry is the largest sourceof jobs with a concentration and diversificationlevel above the state average. The productiveservices also have great economic importance,which suggests that the region can be a supplierof additional or alternative services to the RMSPand that RMSP’s industry can rely on productionservices from the region, especially those whichare more modern in character. In this region, thereis a strong specialisation in IT, concentrating alarge number of companies from various produc-tive segments, educational institutions, researchlaboratories and specialised research centres.Following São Paulo, the metropolitan region ofCampinas is the second largest in the generationof innovations in Brazil and one of the mostadvanced in terms of industrialisation.

The Metropolitan Region of Santos, bycontrast, brings together nine municipalities,being the third largest region of the state interm of its population, with 1.7 million residents

in 2010. Besides Cubatao’s industrial park andSantos’ port complex, the region stands out foractivities related to tourism. The presence of theport of Santos, the largest and most importantof the country, confers great importance to thesupport of export trade activities.

The Metropolitan Region of Vale deParaiba, composed of 39 municipalities, isstrongly interconnected by a network of high-ways with the major Brazilian cities – São Pauloand Rio de Janeiro – and with the MetropolitanRegion of Campinas and is centred around themunicipalities of São Jose dos Campos, Taubate,Canas, Jacarei and Pindamonhangaba. Similarto other regions, its cities are densely popu-lated, with 1.8 million inhabitants in 2010. Thismetropolitan region has a typical industrial andtechnological innovation profile, being the regionwith the highest density of technological andtechnical occupations in the State of São Pauloand the fourth in number of research and devel-opment centres and laboratories in the state.The presence of the Technological Institute ofAeronautics (ITA), the most important aerospaceindustry in the country, enabled the developmentof productive skills, techniques and technology inthe sector.

The Urban Agglomeration of Jundiai,which occupies a strategic position between SãoPaulo and Campinas, the two most dynamic citiesof the macrometropolis, consists of seven munici-palities and is distinguished by its industrial char-acteristics. Its most important cities are Louveiraand Jundiai.

Finally, the Urban Agglomeration ofSorocaba, formed by 19 municipalities, standsout for its diverse agricultural and industrialcharacteristics. Highly developed industrialmunicipalities coexist with economically less-developed municipalities, with activities mainlyfocused on the primary sector. Sorocaba is stillthe main urban centre of the agglomeration,aggregating also municipalities with largerpopulations, such as Votorantim, Itu and Salto.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

68 G. Silva and M. de Lourdes Fonseca

Table 1. Distribution of gross industrial product inselected states of Brazil (%).

States 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1985

Pernambuco 5.0 5.3 4.5 2.6 2.1 2.1 2.0Bahia − 1.3 1.3 1.7 2.5 4.0 5.2Minas

Gerais7.5 7.9 6.5 5.7 6.4 8.9 8.7

Rio deJaneiro

28.0 25.0 20.3 17.5 15.6 11.8 11.8

São Paulo 35.0 39.4 48.9 55.5 58.1 47.0 44.0Paraná − 2.4 2.8 3.2 3.0 4.9 5.2Santa

Catarina− 2.2 2.4 2.2 2.6 4.0 3.6

Rio Gde.do Sul

8.0 9.6 7.9 6.9 6.3 7.3 6.9

Source: IBGE, Research Coordination, Department of NationalAccounts.

several factors such as the economic crisis andthe productive restructuring of the 1980s, decen-tralisation of the manufacturing industry and spe-cialisation in advanced technological and finan-cial services in the 1990s. Nevertheless, in 2008,the State of São Paulo accounted for 33.1% ofBrazilian GDP and 33.9% of the industrial GDP(IBGE 2010).

Some issues should be highlighted regardingthe pattern of urbanisation that accompanied thislong process of industrialisation and development.First, the existence of a centre–periphery relation,between the city of São Paulo (as the epicentre) andthe municipalities comprising the metropolis, isreproduced by the city’s existing centralities, withemphasis on the Central and the Southwest sectorsas its major tertiary centres. Second, is the estab-lishment of a strong spatial socio-segregated for-mation, which clearly defines the areas where eliteand poorer populations concentrate (Santos 1990;Maricato 1996; Villaça 1999). Third, is the coex-istence, outside the more densely populated areas,of low-density residential patterns with ‘islands’ ofvertical integration, demonstrating a strong trend ofhorizontal sprawl – fostered by conurbation areasor by neighbouring municipalities characterised bylower occupation densities. Fourth, and as a prod-uct of the aforementioned trend, is a significant

dispersion or metropolitan fragmentation, resultingin ‘chaotic’ provision of mobility and transporta-tion, network infrastructure equipment and ser-vices such as health, education and public safety.Fifth, as we shall see in detail later, is the occu-pation of land by factories and tertiary companiesalong the main roads connecting the city of SãoPaulo with Campinas, Santos, Sorocaba, Jundiaiand São Jose dos Campos. Ultimately, this land-usepattern led to the construction of a macrometropo-lis that emanates from São Paulo, integrating avast and discontinuous territory, but that maintainsclose production ties among its elements, as partsof a single system.

This sprawled and fragmented pattern ofmetropolitan growth is supported by the vast pre-dominance of automobiles and buses as the mainmeans of public transportation. In the city of SãoPaulo alone, there are more than 5.1 million cars(73% of the fleet of vehicles) and more than800,000 motorcycles, excluding buses, trucks andutility vehicles (Detran/SP 2011). In total, there aremore than 7 million vehicles, mostly concentratedin the macrometropolis, which represent a third ofthe fleet in the State of São Paulo. The primaryeffects of this predominance are widely known:congestion, pollution, traffic accidents, additionalcosts for urban mobility (in terms of infrastructure,equipment, insurance and parking) and conversionof urban spaces into elements of the road system toattend the metropolitan scale.

The preference for road transport modes andthe large spatial dispersion of the metropolis hin-der the implementation of an efficient mass trans-port network. Thus, in addition to the aforemen-tioned transportation and mobility problems, asevere shortage of public transport also affectsthe metropolis. The evolution of the subwaysystem is an indicative example of the deficitbetween urban growth and passenger transporta-tion. Between 1972, when the first line was inaugu-rated, and September 2010, when the Tamanduateístation was partially activated (integrating with themetropolitan railway system), the network reachedan extension of only 69 km – against London’scurrent 400 km, New York’s 368 km and Paris’

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 69

214 km – all of which are smaller cities than SãoPaulo.5

At the same time, the bus system suffers fromstructural problems including overcrowding, poorcoverage, lack of integration and interconnectionbetween lines and modes, a deteriorating fleet,poor quality service (in terms of comfort, reg-ularity and safety) and high cost rates, amongothers.6 According to Biderman, ‘since the 1950s,the transport policies of the Metropolitan Regionof São Paulo, as well as in most other metropolitanregions, have neglected public transport, pedestri-ans and cyclists. The result is an inefficient andchaotic system, with long commuting times, espe-cially for the poor’ (2008, p. 3). In this sense, theState Traffic Authority (CET) estimated that 20%of workers spend more than 3 hours a day on buses.Another 10% spend more than 4 hours to get to andfrom work.7 Aggravating this scenario is the lowdegree of public transport connection between SãoPaulo and other cities belonging to the metropoli-tan area and among other cities in the metropolitanarea, including connection among the main labourhubs (such as the ABC region8).

Moreover, the constant vulnerability to rainowing to soil impermeability, exposing city streetsto dangerous flooding risk, and the sense of expo-sure to urban violence – real or imaginary (a char-acteristic of large Brazilian cities) – turns mobilityinto a critical issue in the development of themetropolis and of the macrometropolis. However,neither of these issues prevents São Paulo fromleading the Brazilian economy.

3. Between the metropolis and themacrometropolis: the city-region

As mentioned earlier, the metropolis (i.e.Metropolitan Region of São Paulo or RMSP) cur-rently extends not only over a vast spatial contigu-ous territory – over the 39 constituting municipali-ties – but also over a wide cities network that todaymake up the so-called macrometropolis whosemain effect is the remodelling of the sheer scale ofmetropolitan development. In fact, the emergenceof a metropolitan region-wide structure in the State

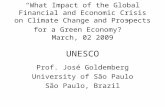

of São Paulo, extending to a 150 km radius aroundthe capital, has been observed since the 1990s.This immense structure, which according to theEmpresa Paulista de Planejamento Metropolitano(EMPLASA), São Paulo’s urban planning author-ity, was consolidated over the last 10 years, bringstogether four metropolitan areas, São Paulo,Campinas, Santos and Vale do Paraíba, and two‘urban agglomerations’, Jundiai and Sorocaba,radiating through a network of highways, linkingthe capital to the interior and to other states (seeFigure 1). This new spatial configuration, formedby the systemic and functional integration ofseveral different areas, constitutes an unprece-dented large urban area in the country. As such,it poses new challenges to interpret the processesdetermined by this dynamic. Inevitably, this willrequire the expansion of the scale of analysis to themacrometropolis level, rather than focusing explic-itly on the metropolitan region of São Paulo alone.

According to Cunha (2008), the formation ofthis macrometropolis is a result of São Paulo’smetropolis sprawling zone of influence towards itsadjacent interior.9 However, this process did notoccur randomly but rather followed a hierarchicalapproach based on the degree of modernity anddynamism proper to each activity, locating the mostmodern activities in the RMSP and decentralisingto its adjacent areas’ routine activities, in searchfor low-cost location areas, but with access to goodinfrastructure. Research results indicate that indus-try is more concentrated in the macrometropolis ofSão Paulo than in the RMSP itself, while the pro-ductive services are relatively more concentratedin the latter. This indicates that other metropolitanareas benefit from the agglomerative advantages ofthe RMSP, especially the most modern productiveservices, which are primarily located in the SãoPaulo municipal area.

The scope of a wide transport network10 is oneof the strategic dimensions of the macrometropolis’configuration, supporting the emergence of numer-ous shopping centres, business centres, logisticsplatforms and residential condominiums, amongothers, transforming this enormous region into avast area of commuters, used daily by millions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

70 G. Silva and M. de Lourdes Fonseca

Figure 1. São Paulo’s macrometropolis.

Note: Area urbana, urban area; estradas, highways; Oceano Atlântico, Atlantic Ocean. Source: http://estadao.com.br/megacidades/macrometropole_map (with adaptations).

of people.11 The RMSP concentrates on most ofthese commutations, mainly occurring between themunicipalities of the metropolitan area itself. It isnoteworthy that a significant number of these com-muter flows are from other metropolitan areas andurban agglomerations in the process of expan-sion, such as Jundiai and Sorocaba (EMPLASA2012). The relatedness and the functional integra-tion observed in this area result in the formation ofa regional area of high complexity.

This spatial dynamic matches its economicimportance. In 2007, the three metropolitan areasof the macrometropolis jointly accounted for68.2% of the state’s GDP. The RMSP contributed

significantly, accounting for 56.4% of the state’sGDP and for 47.9% of the population (EMPLASA2012). Moreover, these industrially developedregions also benefit from important networks ofeducational and research institutions located there,with 72% of research and development centres andlaboratories of the State of São Paulo located inCampinas, São Paulo and São Jose dos Campos(the main city of the Metropolitan Region of Valedo Paraíba). This accounts for the great concentra-tion of technological occupations in these regions,especially in São Jose dos Campos, followed byOsasco, São Paulo and Campinas. For this reason,these regions also concentrate on the most intensive

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 71

technology industries and the largest number ofinnovative companies (Suzigan et al. 2006).

It can be concluded that the formation of themacrometropolis of São Paulo is the result of theadvancement of production units and enterprisestowards the interior regions of the state, within acontext of deep transformations in the accumu-lation regime.12 As noted by Magalhães (2008,p. 16), ‘another important element in the formationof the city-region is the contemporary productionof the space of the industry, marked by flexibil-ity of production processes and the strong need foran agile and easy access to the connecting infras-tructure of the industrial space of globalisation’.However, this occurred in a selective manner, sincethe business functions that require higher qualifi-cations are still concentrated around a few centresand a few geographical axes, polarised by the citiesthat already had a regional economic role. As such,the macrometropolitan region is polarised by a net-work of large and medium cities that, owing to theirsize, tend to concentrate the main economic activ-ities within their respective regions, resulting inhigher productive complexity. This, in turn, createsa network of surrounding smaller municipalities,dependent on the centres for jobs, health servicesand education, among others. That is, although themacrometropolis of São Paulo occupies a privi-leged economic position on the national scene, itembraces municipalities with varying degrees ofurban living quality and development.

4. Challenges of the macrometropolis:discontinuity, imbalance and asymmetries

As mentioned earlier, the São Paulomacrometropolis consists of structures thatelevate its status as the nation’s key economichub: productive units, mass consumption, portand airports, technological centres and so on.However, in its hinterland, the spatial occupationexemplifies large asymmetries: sectors in somecities that polarise and concentrate on economicactivities, work and affluence in contrast toother regions that exhibit peripheral conditionsand dependencies, with large concentrations of

low-income population, dormitory cities, distantfrom employment and service centres. Althoughit extends over a vast territory, the macro-regioncontinues to exhibit a radial-centric model, fea-turing weak ties among its various components.These manifestations of imbalance and asymmetryresult in excessive pendulum movements on thecentre–periphery axis. This, in turn, overloads thepublic transport system and consequently inhibitsintra-urban/metropolitan mobility, reducing thepopulation’s access to quality urban spaces andinfrastructure.

Hence, one of the challenges is to invert thissituation of discontinuities, imbalance and asym-metries. Among other things, this depends on theimprovement in the quality of peripheral spacesand on the creation of multiple centralities inthe macrometropolis, transforming it into a poly-centric city model. This structure would improvethe distribution and decentralisation of jobs, com-merce and public and private services, reducingthe level of dependency in relation to the cur-rently existing nuclei, thus creating opportunitiesand development in areas that are presently definedas peripheries. These new centralities should beserviced by privileged modes of accessibility andshould be conceived as highly dense economicareas, heterogeneous in land use and functionalcomplexity, capable of offering diversified concen-trations of employment, commerce and public andprivate services.

Similarly, an integrated mobility policyframework is required to overcome the currentradial-centric model, creating a network-basedmacrometropolitan structure, improving accessi-bility, especially of peripheral spaces. To achievethis, it will be necessary to improve the roadsystem and the public transport network intercon-necting the region’s various municipalities andreducing private vehicle use.

Notwithstanding, although the macrometropo-lis of São Paulo manifests itself through theinterdependencies of production, consumption andlabour, that is, through people’s daily activities,this spatial organisation is not accompanied byan equally integrated public management and

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

72 G. Silva and M. de Lourdes Fonseca

administration model. In fact, public managementcontinues to be fairly departmental, circumscrib-ing its action to a strictly municipal territory, oftengoverned by politically divergent and competingagendas (whether in terms of political partisanshipor in terms of the adoption of competitive mech-anisms to attract public and private investments).Although the region is officially subdivided intometropolitan regions and urban agglomerations, itdoes not have an administrative body with powersand managerial capacity to deal with the territoryin its totality. The RMSP was officially created in1973, but this did not result in the implementa-tion of effective planning measures, which wereoften restricted to specific issues such as trans-portation. Even then, the planning effort did notresult in concrete region-wide policies. Similarly,the remaining and recently created metropolitanregions lack spheres of governmental coordination.

5. The strategic agenda: globalisation andgovernance

Returning to the article by Allen Scott et al. ([1999]2001), the authors note that the city-region (poly-centric, comprehensive and socially and spatiallysegmented) resembles a chessboard, in which thestrategic position of the pieces (investments) couldbe decisive to extend or reduce competitive powerin an increasingly globalised world. They also pointout that this new territorial and productive con-figuration relies often on inadequate institutionalstructures and planning for the maintenance of eco-nomic and social health. Accordingly, we believewe can take a step ahead by framing the challengesof the macrometropolis of São Paulo in terms ofglobalisation and governance.

5.1. Globalisation

Saskia Sassen affirms that São Paulo is themost powerful city in Latin America, ahead ofMexico City, Santiago de Chile and BuenosAires, leading in power to attract resourcesand in the sophistication of the knowledgeeconomy. The author notes that ‘[The city] is

appropriate for associated complex sectors, suchas finance, software development, legal knowledge,accounting, consulting, and advertising. It has agood stand in economic power, but not so much as abusiness center’ (Sassen 2008, p. 21). Although theauthor avoids applying the adjective ‘global’, it iswithout doubt that in São Paulo the effects and thedynamics of globalisation acquire a strong territo-rial expression, now understood in its metropolitanand macropolitan dimensions.

We can see this from the debate on the‘deindustrialisation’ process of some traditionallyindustrial sub-metropolitan areas, such as the SãoPaulo’s ABC region. During the 1980s and 1990s,there were great and profound changes in the pro-ductive profile of this region that, in general, werelinked to loss of competitiveness owing to globali-sation’s economic effects. However, when the anal-ysis is extended to the macrometropolitan scale,one can observe the emergence of new produc-tive spaces based on the development of industrialtechnology and innovation complexes, which is thecase in Campinas and São Jose dos Campos. Thus,globalisation opportunities (at least for large com-panies) appear more clearly outlined in the State ofSão Paulo.13

What about the other dimensions (social andenvironmental)? In fact, this is the great challengefor São Paulo’s metropolis and macrometropolis.On the one hand, the new integrated regional terri-tories ‘decompress’ metropolitan problems via theopening of new ‘frontiers’ of occupation, whetherin housing or in terms of economic activities.On the other hand, the tendency exists to repro-duce and disseminate urbanisation patterns thathave and still continue to characterise the cityof São Paulo: dispersion, fragmentation, segre-gation, speculation, illegal occupation and riskyareas, with the consequent deficits – housing,mobility transport (public), education and health,among others, depending on income levels and onthe location of the different social groups in themacrometropolis. Hence, and this must be high-lighted, globalisation does not seem to favour theresolution of old and persistent problems of urban-isation in Brazil.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 73

5.2. Governance

The institutional challenges embedded in thedevelopmental dynamics of the metropolis andmacrometropolis lead us to another point to behighlighted: governance. As is well known, theconcept of governance is polyvalent, and its use todesignate governmental practices to alter the tradi-tional nature of state policies has gained strengthand legitimacy since the 1990s. In general terms,while ‘governability’ refers more to the dimen-sion of the exercise of state power, ‘governance’refers to coordination and cooperation standardsbetween social and political actors participatingin public policy agenda-setting (Gonçalves 2005).Therefore, the concept of governance comes intoplay to designate a strategic vision of develop-ment that involves articulation, recognition andparticipation of social actors in government deci-sions. It also refers to the conditions and processesleading to this practice.

We can test the concept of governance inthe case of the ABC region in the metropolitanarea of São Paulo based on the liaison move-ment among municipalities that belong to theregion: Santo André, São Bernardo, São Caetano,Diadema, Mauá, Ribeirão Pires and Rio Grandeda Serra, which occurred in the second half of the1990s (Klink & Cidade-Região 2001). At the time,the so-called regional movement coalesced aroundthe Intermunicipal Chamber and the Greater ABCIntermunicipal Consortium that brought togetherlocal governments, entrepreneurs and represen-tatives of civil society for the development ofthe region. Simultaneously, the process raisedquestions regarding the viability of a metropoli-tan government sphere linked to the state appa-ratus and the traditional forms of planning –institutionally designed in the 1970s,14 but withno success. Although the movement was unableto continue in this demarche, it bequeathed aregional development agency, an innovative expe-rience and, as such, a new governance perspec-tive to be renewed in the future (Cocco & Silva2001).

Yet again, the change in the scale of themetropolis’ development dynamic towards that of

a macrometropolis raises new challenges. Insofaras the set of cities (some with metropolitan status,as seen earlier) work in an increasingly intertwinedmode (see, e.g. the expansion of shuttle servicesbetween São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, via theViracopos airport in Campinas15), the definitionof public investment criteria and ways of planningand managing land require at least an update ofstrategies. What would be the sphere to negotiateor agree on the cities’ demands? How to establishinvestment priorities? What are the institutionalconditions that make this new configuration moreproductive? Certainly, the propositions cannot beframed within traditional models of metropolitanagencies, especially when we consider they neverleft project proposal status.16

6. Conclusion

Until very recently, research related to the growthof large cities in south-eastern Brazil concen-trated on development dynamics of the São Paulometropolis. With its 19 million inhabitants, it was(and indeed still is) the main centre of indus-trial and financial development of the country, inaddition to being the main hub for the produc-tion of scientific and technological innovations.However, what we attempted to show in this arti-cle is that the scale of reference has changedand that the metropolitan question can no longerbe interpreted without taking into account thenew determinants of the São Paulo macrometropo-lis, taking into consideration the interaction withother metropolitan urban centres characterisedby social, economic and environmental singular-ities, and which cannot be considered as mereoutskirts.

The macrometropolis of São Paulo providessufficient evaluative elements to consider it interms of ‘city-region’: productivity growth basedon the dissemination of productive arrangementsof a new kind (flexible, logistic and high-tech);territorial expansion in regional scale; scope ofurban and rural areas and strategic importanceof transportation and communication networks.It is worth mentioning the fact that this dynamic

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

74 G. Silva and M. de Lourdes Fonseca

development corresponds with the ongoing globalintegration processes, which provides this area aspecial interest: on the one hand, as a territory ofproductive activities and technological innovation(either in major urban centres or adjacent to majortraffic routes) and on the other hand, as the territoryof social life and work linked to these economicactivities.

In view of this, the question remains of under-standing how development processes at the variousscales and productive dimensions can be territori-ally articulated to avoid favouring perverse effectssuch as the dominance of corporations or the state’stechnocratic rationality over the opportunities forall those who inhabit the city-region (after all, thesocio-spatial contradictions that have accompaniedthe development of the city of São Paulo havenot disappeared overnight with the emergence ofthe macrometropolis; to the contrary, these havebecome more imperative). In this sense, Baudouinand Collin (2012) argue in favour of mechanisms ofgovernance that are capable of mobilising the cre-ative and initiative potential of citizens and whichcollectively achieve solutions that are up to thesechallenges. How to do this?

Although the answer to this question is obvi-ously beyond the scope of this article, our analysisprovides elements for a broader agenda. First, moreanalytical work and debates on the concept of themacrometropolis should be undertaken to provideit with theoretical and empirical consistency (asa precondition for knowledge). Second, a moreintense dialogue should be set up between the insti-tutions of the state, academia, the third sector andsocial movements and aimed at building a workingagenda of common interests in these complex ter-ritories (as a precondition for strategies of publicgovernance). Third, and finally, we should not losetrack of the political dimension of these discus-sions, contrary to the technocratic perspective thatusually permeates the state in Brazilian approachesto urban and regional planning. Although the aboveset of issues does not represent a definitive ‘solu-tion’, it could provide a starting point for anagenda of broader transformations in the São Paulomacrometropolis.

Notes1. In Brazil, the geographer Milton Santos called

these environments ‘the technical and scientificinformational domain’ (Santos 1997). On theimplications of the concept of the technicaland scientific informational domain in Brazilianmetropolisation process, see Silva (2009).

2. The importance of the logistic dimension in thenew industrial world is often underestimated.At best, it is seen as a function of the supplychain and, at worst, as an appendix of transporta-tion activities. In fact, logistics is now the verymatrix of industrial organisation, whose circulationand distribution networks enable the integrationof entirely different productive territories into theplanetary or global scale (Silva 2003).

3. The Metropolitan Region of Vale do Paraíba wascreated by state law in January of 2012.

4. ‘Bandeirante’ means a socio-historical figure ofSão Paulo characterised by boldness and the abilityto organise the penetration of unexplored fron-tiers of Brazil during the colonial period, look-ing mainly for mineral wealth and native slaves.In later times (contemporary), that figure was usedas a symbol or representation of part of Brazilianidentity.

5. Even considering subway and train lines dedi-cated to passenger transportation in the metropoli-tan area, the network of 313 km representsonly half of London’s, Berlin’s or New York’ssystem.

6. Biderman (2008) points out that the introductionof the Single Ticket, in 2004, which allows usersto pay a flat rate regardless of distance or numberof transshipments, reinvigorated the use of publictransport.

7. The origin–destination survey of the São Paulosubway, conducted in 2007, also indicated thatthe walking trips accounted for 33.13% of totalmobility. This decreased mobility is due to thecombination of reduced real income with therise in the transport fare rate, which means thatmost of the population living in slums, housingprojects and poor neighbourhoods have restrictedtheir daily lives to their own district or neighbour-hood (Diretoria de Planejamento e Expansão dosTransportes Metropolitanos/SP 2008).

8. The ABC region of São Paulo, located in themetropolitan area of São Paulo, is considered thecradle of industrialisation, especially by the pre-dominant presence of the auto industry since the1950s. It is the main reference in Brazil of aFordist-type industrialisation model, which enteredinto crisis in the 1980s and 1990s (Klink & Cidade-Região 2001).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 75

9. Zanchetta (2008) describes this process as sprawl-ing urbanisation linked to the development of acirculation system that brings together differentmetropolitan areas, without geographical contigu-ity; ‘the growth of the macrometropolis refers tohighways, the wide roads of the United States[that line up] the condominium, the universityjust ahead, a few miles down the mall, next tothe slum, and linking them, only the highway’(Zanchetta 2008, p. 63). The author refers to therecent installation of companies such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi, AGA and Akzo Nobel along roads inthe Campinas–Itu–Jundiai triangle, which showsthe type of logistics strategies in play in this newcontext of the macrometropolis.

10. The macrometropolis support network began to bebuilt in the late nineteenth century through theSantos–Jundiaí and Sorocaba railroads, linking thestate capital to the port of Santos and the coffee-producing areas in the state. The old network wassuperposed, in the 1950s, by an important roadnetwork centred on the city of São Paulo. Thesetrain and bus networks not only allowed the expan-sion of the city of São Paulo but also transformedthe city into a real crossroads network that con-nected the various producing regions, consumersand suppliers of inputs and raw materials, beingfundamental to its conversion to the greatest ser-vice and industrial centre of Brazil. Currently, thefact that this macrometropolitan region is the siteof three major airports in the country – Guarulhos,Congonhas and Viracopos – and the main port– Santos – reinforces its centrality not only inrelation to the national territory, but also in itscommunications with the international network ofcargo and passengers.

11. The transportation of cargo produced in themacrometropolis equals approximately 65% of theState’s total. The movement of passengers has alsoa significant density corresponding to 95% withrespect to the sources and about 97% in relation tothe destinations (Governo do Estado de São Paulo2010).

12. The concept ‘regime of accumulation’ was devel-oped by the French Regulation School to charac-terise ‘the set of regularities that secure a generaland relatively coherent progression of the accumu-lation of capital’ (Boyer 1990, p. 71). It refers toan intermediate category between the traditionalconcept of mode of production and the economicand social determinations in the short term.

13. Certainly, the concentration and synergies ofdifferent components of the macrometropolisfavoured the accumulation of large capital,facilitated by mergers, acquisitions and theconcentration of infrastructure and highly skilled

workforce in this region. It was on these termsthat São Paulo took on globalised functions ofproductive command and control.

14. In Brazil, the metropolitan areas were created in1973 with the establishment of eight metropolitanareas, including São Paulo (Rio de Janeiro wouldbe integrated in the following year after it resolvedissues resulting from its status as the country’sformer capital). Despite this, none of them man-aged to establish themselves as major agents ofmetropolitan development. As for the metropoli-tan regions of Campinas and Santos, they werecreated via state complementary laws in 1996 and2000, respectively. As mentioned on Note 3, theMetropolitan Region of Vale do Paraíba was alsocreated by state complementary law in January2012.

15. The (strong) relationship between the cities of Riode Janeiro and São Paulo is founded largely on the‘shuttle service’ between Santos Dumont airport(Rio de Janeiro) and Congonhas (São Paulo). Witha much smaller role, Galeão (Rio de Janeiro) andGuarulhos (São Paulo), both international airports,are also used for this function. However, recently,the Viracopos airport (Campinas) was also inte-grated via a shuttle service with Rio de Janeiro,re-enforcing the strong integration between thetwo macrometropolitan cities of São Paulo andCampinas, which have become alternative airports.

16. The difficulty for the metropolitan agencies to sur-pass the ‘project phase’ is explained, in part, by thevery configuration of federalism in Brazil, whichonly recognises government, states and municipal-ities as instances of the Union. This configurationdoes not institutionally favour coordinated actionsin the metropolitan areas (Garson 2009).

Notes on contributorsGerardo Silva: is a geographer and holds a PhD inSociology; he is a faculty member of the program inTerritory Planning and Management, Federal Universityof ABC, São Paulo, Brazil.

Maria de Lourdes Fonseca: is an architect and holds aPhD in Urbanism; she is a faculty member of the pro-gram in Territory Planning and Management, FederalUniversity of ABC, São Paulo, Brazil.

ReferencesBaudouin T, Collin M. 2012. Fazer metrópole por meio

da democracia. In: Albagli S, Cocco G, editors.Revolução 2.0. Da Crise do Capitalismo Global àConstituição do Comum Rio de Janeiro: Garamond;p. 207–223.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014

76 G. Silva and M. de Lourdes Fonseca

Biderman C. 2008. Infra-estrutura de transporte urbanode São Paulo. [Internet]. [cited 2012 Mar 13].Available from: http://www.urban-age.net

Boyer R. 1990. A Teoria da Regulação. Uma análisecrítica. São Paulo: Nobel.

Castells M. 1989. La Ciudad Informacional. Tecnologiasde la Información, Reestructuración Económica y elProceso Urbano-regional. Madrid: Alianza.

Cocco G, Silva G. 2001. A Agência de Desenvolvimentodo Grande ABC paulista: entre a agenda regionale a ação territorial. Santo André: Agência deDesenvolvimento Econômico do Grande ABCpaulista. Research Report.

Cunha AA. 2008. Desenvolvimento e espaço: dahierarquia da desconcentração industrial da RegiãoMetropolitana de São Paulo à formação daMacrometrópole Paulista [Unpublished Mastersdissertation]. FFLCH-USP: São Paulo.

Detran/SP (Departamento Estadual de Trânsito de SãoPaulo). 2011. Frota de Veículos de São Paulo 2011.[Internet] [cited 2012 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.detran.sp.gov.br

Diretoria de Planejamento e Expansão dos TransportesMetropolitanos/SP. 2008. Pesquisa origem e destino2007. Região Metropolitana de São Paulo. Síntesedas informações pesquisa domiciliar. São Paulo:DM. Technical Report.

EMPLASA (Empresa Paulista de PlanejamentoMetropolitano). 2012. Macrometrópole. [Internet][cited 2012 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.emplasa.sp.gov.br

Garson S. 2009. Regiões Metropolitanas: Porque NãoCooperam? Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital.

Gonçalves A. 2005. O conceito de governança. [internet][cited 2012 Mar 15]. Available from: http://conpedi.org.br/manaus/arquivos/anais/XIVCongresso/078.pdf

Governo do Estado de São Paulo. 2010. Estudo daMorfologia e da Hierarquia Funcional da RedeUrbana Paulista e Regionalização do Estado de SãoPaulo. São Paulo: Secretaria de Estado de Economiae Planejamento (SEP)/EMPLASA/FundaçãoEstadual Sistema de Análise de Dados (Seade).

IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística).2010. Participação dos Estados no PIB Nacional.Brasília: IBGE.

Klink J, Cidade-Região A. 2001. Regionalismo eReestruturação no Grande ABC Paulista. Rio deJaneiro: DP&A.

Magalhães FNC. 2008. Da metrópole à cidade-região. Na direção de um novo arranjo espacialmetropolitano? Revista Brasileira de EstudosUrbanos e Regionais (RBEUR). 10/2:9–27.

Maricato E. 1996. Metrópole na periferia do capitalismo.São Paulo: Hucitec.

Santos M. 1990. São Paulo: metrópole corporativa efragmentada. São Paulo: Nobel.

Santos M. 1997. A natureza do espaço. São Paulo:Hucitec.

Santos M. 2005. A urbanização Brasileira. São Paulo:Edusp.

Sassen S. 2008. Entrevista. Jornal O Estado deSão Paulo. [Internet] [cited 2012 Mar 23].Available from: http://estadao.com.br/megacidades/entrevista_saskia.shtm

Saxenian A. 1994. Regional advantage: culture and com-petition in silicon valley and route 128. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press.

Scott A, Storper M. 1986. Production, work, territory:the geographical anatomy of industrial capitalism.Boston and London: Allen & Unwin.

Scott A, Agnew J, Soja E, Storper M. [1999]2001.Cidades-regiões globais. Espaço & Debates. Revistade Estudos Regionais e Urbanos. XVII/41:11–25.

Silva G. 2003. Logística e território. Implicações para aspoliticas públicas de desenvolvimento. In: Silva G,Monié F, editors. A mobilização produtiva dos terri-tories. Instituições e Logística do DesenvolvimentoLocal. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A; p. 81–98.

Silva G. 2009. O meio técnico-científico informacionale os novos territórios metropolitanos. RevistaPeriferias. 1/2:132–145.

Soja E. 1990. Postmodern geographies. The reasser-tion of space in critical social theory. London:Verso/New Left Books.

Suzigan W, Furtado J, Garcia R, Sampaio S. 2006.Inovação e conhecimento: indicadores regional-izados e aplicação a São Paulo. Revista deEconomia Contemporânea (REC) (Internet). 10/2:323–356.

Villaça F. 1999. Efeitos do espaço sobre o social nametrópole brasileira. In: Souza MAA et al. editors.Metrópole e globalização. Conhecendo a cidade deSão Paulo. São Paulo: Cedesp;p. 221–236.

Zanchetta D. 2008. A primeira macrometrópole do hem-isfério sul. Jornal O Estado de São Paulo. [Internet].[cited 2012 Mar 23]. Available from: http://estado.com.br/megacidades/sp_mancha.shtm

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

"Que

en's

Uni

vers

ity L

ibra

ries

, Kin

gsto

n"]

at 1

1:53

20

Aug

ust 2

014