ryanrichtersbseportfolio.files.wordpress.com · Web viewNoticias del Puerto de Monterey (Monterey...

Transcript of ryanrichtersbseportfolio.files.wordpress.com · Web viewNoticias del Puerto de Monterey (Monterey...

David Jacks: A Ruthless Californian Business-manRyan RichterSocial & Behavioral ScienceCalifornia State University Monterey BaySpring 2018Capstone Advisor: Dr. Rebecca BalesMay 18th, 2018

Richter 1

AbstractThis paper analyzes the life of Californian businessman and land baron David Jacks. Born in Scotland, he came to the United States during the Californian Gold Rush of 1849. After he found work in the city of Monterey, he rose to become a wealthy landowner who was respect by many, and hated by some. He was involved in many court battles, including one that reached the US Supreme Court in 1906. Using a variety of sources, this paper identifies key concepts which contribute to his success as a business man, and ultimately his prowess in maneuvering through the judicial system, which further aggravated his enemies. Contemporary social theory is applied to Jacks in order to better understand how he made his mark on Monterey and Cali-fornia history.

Richter 2

Table Of ContentsIntroduction …………………………………………………………………………4Historical Background ………………………………………………………….…..7California: From Mexican Independence to US Statehood………………..….……11David Jacks: The Old-West Entrepreneur………………………………………….16Pueblo Land and the Supreme Court……………………………………………….23

Social Theory: Land Tenure…………………………….…………………………..28

Conclusion: Habitus…………………………………………………………….…..32Connection to Service Learning…………………………………………………….36Map of the Pueblo Lands of Monterey………………………………….……….….39Bibliography …………………………………………………………………….….40

Richter 3

IntroductionDavis Jacks importance to Monterey is an example of the impact one individual can have on history. Had there been no David Jacks, the developmental path of Monterey would have been drastically different. Although a prominent figure, he was a product of his time. The social conditions surrounding Jacks at the time influences his actions and the course the region took through history. After leaving Scotland to pursue a new life in the United States, David Jacks immigrated to New York in 1846. Upon hearing about the Gold Rush, Jacks moved to San Francisco in 1849. He came to Monterey in 1852 after deciding to pursue his interests in owning land. After the end of the Mexican-American War, and the signing of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the turnover of former Mexican land to the US state of California began. This is a time ripe for bud-ding land owners to take advantage of three types of land left over by Mexico: ranchos, former Church properties, and pueblos.1 In Monterey, David Jacks comes into a prominent position as a subdivider of these land grants. It is because of the circumstances revolving around the transi-tion of the land from Spanish, to Mexican, and finally to American control that David Jacks was able to come into Monterey and influence the region with his business practices as a landowner. The land use of the Monterey has changed under the occupation of different groups of people. The region has been inhabited with people beginning with native tribes such as the Ohlone and Esselen, followed by periods of Spanish rule from the late 1600’s to 1821, then Mexican rule until 1846, and, finally, becoming incorporated into US jurisdiction as the state of California in 1850. The role of the land initially developed around mission-agricultural use con-trolled by the Spanish priests and monks, and the presidio, controlled by the Spanish govern-ment and military. There was often conflicting interests between the goals of the mission, and thus the Church, and the intentions of the presidio regarding the development of the local area.2 Monterey was valued for its proximity to arable land for farming. Due to abundance of food and work, farm workers from all over California were drawn to Monterey, which helped the population grow in size. The changes in the social make-up of the Monterey region reflect the changes in gover-nance. At first, the economy was largely driven by the mission agriculture system and as a mili-tary fort, and this was sustained for a while until it primarily became agricultural, and much later a fishing industry. The changes reflect the population at the time, which add distinction to each era. Major changes evident at this time are the result of David Jacks, beginning in 1852. History has described him as a man who had a “voracious appetite for land”3 who bought much of the Monterey Peninsula before developing the land and selling it in large chunks. The way that he bought land and sold it influenced how the local area became populated, including how much of the land is still natural and undeveloped. He is the reason the communities of Pebble Beach and Del Monte forest came to be, and why many parts of the peninsula have been pre-served and remained unexploited. If not for his acquisition of land, the Monterey Peninsula could have succumbed to overuse resulting in overpopulation and a larger presence of industry because of the interests of corporations at the time.Was David Jacks an opportunist, who took advantage others through his business prac-tices? Or was he doing his best job as a land developer, as a result of the limited regulation of land acquisition at the time? Perhaps he is a bit of both, a ruthless businessman while being a family and religious man at the same time. This capstone sets out to prove that because of the social, political, and cultural environment at the time, Jacks was in the right place at the right time to make a historically significant impact to the development of Monterey.

1 Virginia W Stone, “Who was the real David Jacks?” Noticias del Puerto de Monterey (Monterey Historical and Art Association) 1989. 40: 3-132 John Walton, Storied land: Community and Memory in Monterey. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 2003. 11.3 Bob Kohn. "Jacks County." Dr. Hart's Mansion - Pacific Grove, California. 2008.

Richter 4

Historical BackgroundUnderstanding the historical context which led up to 1850s Monterey is vital to under-standing why Davids Jacks had an impact on the region. In order to obtain this historical infor-mation, I have been reading books and articles on the subject of Californian history. So far, the most important historical literature I have been pulling my information from are Storied Land by John Walton, and “Who was the Real David Jacks?” By Virginia Stone, along with smaller arti-cles written on Jacks found in journals and online. Much of what I am analyzing are primary source documents.The earliest history of California dates back to the history of the first Native Californians. In the centuries before the Spanish colonized the region that is now known as California, the area was inhabited by multiple groups of Native Americans living along the coast, river valleys, and mountains. Author James Rawls notes in his book Indians of California: The Changing Image that before 1750, only a handful of Europeans set foot in the area. Spain entered California with the intention of including the Native population within their empire, through exploitation.4 Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo was the first European to enter into what is now California, he sailed into what is now known as San Diego Bay in 1542, claiming the land for Spain. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake sailed up the coast adjacent to San Francisco Bay, claiming the land for England. The first European to enter Monterey Bay was Sebastian Vizcaíno in 1602, naming it after the viceroy of New Spain. After Vizcaíno left, 168 years would pass until Monterey Bay would be visited by another European.5

Around the mid-1700’s, the Spanish Empire decided to expand from New Spain (present

day Mexico) to include the land to the north which now encompasses the present-day western

US. Historian Steven Hackel wrote about the expedition led by Gaspár de Portolá along with

Junípero Serra. These two Spaniards ventured north through the new territory, establishing the

mission system along the way.6 From 1769 to 1821, 21 missions were established between San

Diego and Sonoma, including two in the immediate Monterey area. The introduction of the mis-

sions forever changed the sociocultural landscape of California.

In1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain. The new nation of Mexico now inher-

ited a vast sum of land, including all of California. The Mexican government stopped support of

missions and halted any further establishment in their new territory. The main reason is that the

primary purpose of the missions, the settlement of land, had been carried out by the early 1800s.

In his book Mexicanos: A History of Mexicans in the United States, Manuel Gonzales describes

that the end of the mission period, known as secularization, was posed by the new Mexican gov-

ernment.7 By 1833, Mexico decided that all former mission land would be handed over from the

4 James J. Rawls. Indians of California. The Changing Image. (University of Oklahoma Press, 1988), 4.5 John Walton, Storied Land: Community and Memory in Monterey. (Berkeley: University of Cali-fornia Press, 2003), 10. 6 Steven W. Hackel, Junípero Serra: California's Founding Father. (New York: Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), 156.7 Manuel G. Gonzalez, Mexicanos: A History of Mexicans in the United States, (Bloomington: Indi-ana University Press, 2009), 62.

Richter 5

Catholic Church to the the Mexican government, with much of the land going to pueblos, or land

set aside for the development of towns.

A prominent theme in Mexican and Californian history is the rancho period. Ranchos are tracks of land to be used for animal husbandry, such as raising livestock like cattle and sheep or horses. Ranchos were considered land concessions, a type of land lease agreement. These lands were meant to be used and then given back to the government after a set period of time. Starting in 1780 during the Spanish period, these ranchos were first established by the Spanish govern-ment, lasting until about 1880 after the final Mexican ranchos were dissolved by the state of Cal-ifornia. Originally, these land grants were for disabled Spanish soldiers to recognize their mili-tary service, however being a friend of the governor was also effective at earning a rancho.The period between 1833 and 1848, when California became a US territory with the sign-ing of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, coincides with the golden age of the ranchos. People who owned ranchos at this time were considered the leaders of the Californian social and political spectrum, as the ranchos were the driving force of the pre-Gold Rush Californian economy. Un-der Mexican rule, the rancho definition changed. No longer were the rancho land grants leased from the government to individuals, instead they became private property. People who owned ranchos during the Spanish period were able to carry over ownership to the Mexican period. As of 1833, ranchos were offered as incentive to populate California. Altogether, the Spanish and Mexican governments sold approximately 500 ranchos, taking up 10 million acres with the largest individual ranchos covering 50,000 acres maximum. Many families owned multiple sepa-rate land grants adjacent to each other, working around the system to own a space of over 300,000 acres.The land that missions owned became public. As a result of new Mexican rule the Catholic Church became dispossessed of the land. The former mission land was turned into more than 300 individual ranchos, comprising a majority of the ranchos gifted by the government. Un-fortunately, the rancho system almost completely ignored the intended use of land missions owned after their relinquishment: to return the land to the Native people. A few Native Californi-ans did inherit back their mission land, however, many lost their land to the mass influx of new rancho owners. In 1852, David Jacks came into a prominent position as a subdivider of former Mexican rancho land grant property, and his business practices and ethics will be analyzed in my capstone.

Richter 6

California: From Mexican Independence to US StatehoodCalifornia was a remote northern province of the nation of Mexico in the years immedi-

ately following Mexican Independence from Spain in 1821.8 Officially, this land was titled Alta

California. This land was an area with huge cattle ranches known as ranchos. This industry

quickly took the dominant position in early California Society. This industry attracted settlers

and traders, who served as a sign of what is to come next during the Mexican American War of

1846-48.

The colonies of Spain gradually began to seek freedom after three centuries of rule. The

nation of Mexico began after declaring independence in 1821. Mexico’s independence was the

result of a bloody, eleven year struggle against Spanish colonial rule. Meanwhile in California,

life went on slowly. Not much changed as a result from the war and independence, other than the

secularization of the missions. The secularization process of the missions divided up the former

mission lands, and decreased the amount of influence the missions had on local affairs. The most

prolific way in which the former mission land was used was the establishment of the ranchos.

Within the ranchos, a few families became the elite land owners, while most of the work was

performed by Californian Native Americans who no longer had work within the mission system.

For the rancheros, those who own the ranches, life was fairly easy. In the years before the Mexi-

can American war, not much was happening politically in California. Other than managing their

land, Californian rancheros occupied themselves by trading goods with the United States by ship,

and partaking in local festivities like weddings and bull fights.

Inspired by the American Revolution of 1776, the colonists of New Spain decided to ob-

tain liberty in the early 1800s. On September 16, 1810, a priest by the name of Miguel Hidalgo

made a passionate speech from the town of Dolores. This speech lit the fire of the war that would

8 Albert Hurtado, Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003) xxvii.

Richter 7

eventually culminate in the establishment of Mexico as a nation.9 For the most part, the province

of California was uninvolved in this struggle. In 1818, two revolutionary ships pillaged a few

settlements on the Californian coast, however there was no other instances of direct association

with the war. The war took place primarily in Mexico to the south of California, eventually end-

ing in 1821 when Mexico achieved independence. Once the news of independence from Spain

reached the capital of California at the time, Monterey, the flag of Spain was lowered and the

new Mexican flag bearing an eagle and a snake was raised.

After independence, the new Mexican government decided to dissolve the mission sys-

tem. From the onset, the missions were designed to be temporary institutions. Once Christianiza-

tion was achieved, the missionaries were to be replaced by a secular clergy and the mission lands

were to be divided up, in a process called secularization. After independence was achieved, de-

mand for secularization increased. Under the constitution of the Republic of Mexico, equality

was assured among citizens regardless of race. Therefore, the missions, which denied Native

Americans of basic civil liberties, were deemed unconstitutional by the new government. In ad-

dition, the Mexican government observed that the missions slowed economic development be-

cause they controlled swaths of unused agricultural land and used indigenous labor. In 1834, the

secularization of the missions officially began.10

According to the 1834 proclamation, half of the land of the missions would be returned to

the Native Americans. Unfortunately, most of the land did not return to the Native Americans.11

They received a portion of the land overall, but nothing like that which was promised.12 Within

9 Timothy Henderson. The Mexican Wars for Independence. (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2009), 104.10 Bill Yenne. The Missions of California. (San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Press, 2004), 18.11 “Secularization and the Ranchos.” Monterey County Historical Society12 Lisbeth Haas. Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769-1936. (Berkeley: Univer-sity of California Press, 2011), 60.

Richter 8

two years of the proclamation, all 21 California missions were secularized. The administrators in

charge of the secularization process sold off the land, along with the cattle, that was intended for

the Native Americans.

The majority of the former mission lands were sold to Californio families, which would

soon become the rancho elite. These families gathered their wealth from the massive rancho that

each family received in the form of a land grant. Each grant was issued with a diseño, a map of

the rancho.13 The maximum size for an individual rancho was 50,000 acres for one family, how-

ever this often was superseded by giving individual multiple rancho grants.

As with he time of the missions, the ranchos depended upon Native American labor. Typ-

ically, ranchos employed about two dozen Native Americans, with some of the largest ranchos

employing several hundred. Both former mission Indian workers and new indigenous workers

were employed at this time. Usually their work was spent in the fields. However, some became

skilled vaqueros. Similar to the missions, most of the workers were compensated only with food,

clothing, and shelter. Their lifestyle was similar to that of serfs. Perhaps the rancho period can

best be compared to feudal society, where the owners of the ranchos held dominion over their

workforce. They maintained power through any means necessary, from persuasion to violence.

The politics surrounding the governance of the province of California at this time were

turbulent. From 1831 to 1836, California had over a dozen governors appointed by Mexico. Cali-

fornios were dissatisfied with the distant nation of Mexico governing their affairs, and sought

more political freedom. In 1836, Juan Bautista Alvarado led a revolt which took the capital of

13 Robert Cleland, The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California, 1850–1880, (The Hunting-ton Library, 1975)

Richter 9

Monterey.14 He declared California a free nation. However, Mexico was not fond of this small

revolution and offered him the position of governor, of which he accepted.

During the Mexican ruled years, California saw a steady increase in the amount of set-

tlers from the United States.15 Initially, those traveling from the US to California were sea otter

hunters, who sold and traded their pelts. These hunters came by ship, which was much easier

than traveling overland. Interest in settling California as a US state increased during the early to

mid 1840s. In 1846, the US declared war on Mexico. During the war, California was seized by

the American military. The idea of Manifest Destiny inspired the United States to expand its bor-

ders to the Pacific coast of the continent. The US landed soldiers on the coasts of California, who

claimed the land with only some resistance from Mexican soldiers. Prior to US military forces

landing in California, a small uprising occurred in a small down just north of San Francisco Bay.

In June of 1846, a small band of American settlers of the town of Sonoma seized control of the

local Mexican government and declared California independent from Mexico. The new nation

was called the “California Republic” and remained independent until US forces arrived a month

later in July. This event was known as the Bear Flag Revolt, named after their flag which directly

inspired the modern California state flag. On July 7th, 1846, Commodore Sloat of the US Navy

captured Monterey and raised the US flag on the Presidio overlooking the Monterey Bay.16

The war in California ceased in January of 1847, and the entire war ended officially on

February 7th, 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty outlined the

transfer of over 500,000 square miles of land to the US, which would eventually become the

states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. For Mexico, this war was a

14 Robert Miller. Juan Alvarado Governor of California, 1836-1842. (Norman: University of Okla-homa, 1998)15 “The California Cattle Boom, 1849-1862.” Monterey County Historical Society.16 Aubrey Neasham. “The Raising of the Flag at Monterey, California, July 7th, 1846.”

Richter 10

tragic loss. Essentially, Mexico transferred half of its land to the United States. For the US, this

victory assured Manifest Destiny for its citizens.

Richter 11

David Jacks: The Old-West Entrepreneur

David Jacks, the largest landowner in Monterey County, California, was a capitalist who

was instrumental in the development of the agricultural industry in the Monterey region during

the middle to late nineteenth century. In the course of his acquisition and development of the

land, David Jacks became familiar with the law, especially land law, and how to apply it with re-

spect to Mexican land grants.

Robert Louis Stevenson, observed that "Land thieves, land sharks, or land grabbers,”

were all common in the descriptions of California land holders in the mid-to-late 1800s.17

Stevenson described one man who owned all the pueblo lands of old Monterey, who was “hated

with a great hatred.”18 David Jacks, an immigrant of Scottish descent who owned the largest

amount of land in Monterey County, California. He was born in 1822 in the Scottish town of

Crieff, and grew up as a devout Protestant. In 1841 at age 19, Jacks immigrated to New York and

found a job as a store clerk in Williamsburg and at Fort Hamiliton.19 Jacks sailed from New York

to San Francisco on 14 December 1848. He arrived in April, 1849 and brought with him $1500

worth of goods to a region booming with a gold rush. This was the first business deal of Jacks

long career in California; he was able to turn his $1500 investment into a $2500 profit. Later in

1849, he purchased a ticket on a steamer and journeyed to Monterey, the former capital of Mexi-

can-controlled Alta California. On Tuesday, 1 January 1850, David Jacks arrived in Monterey.20

Jacks developed a sense for land and land acquisition as he became involved with the city

of Monterey. Soon, Jacks learned to specialize in land acquisitions, and his favorite method of

17 Robert Luis Stevenson, The Old Pacific Capital. (San Francisco, Colt Press, 1944), 47.18 Stevenson, 47.19 Henry D. Barrows, Memorial and Biographical History of the Coast Counties of California,(Chicago, The Lewis Publishing Company, 1893), 241.20 Barrows, 242.

Richter 12

expanding his interests was investing and foreclosing on land. In addition, he developed and uti-

lized the land he acquired to make a profit. In pursuing this style of life, Jacks demonstrated how

the navigation of land acquisition and management, economic resources, political influence, and

legal knowledge allowed him to become Monterey’s most prolific entrepreneur. Jacks demon-

strated a diverse approach when developing his land. He used his lands in different ways ranging

from herding sheep for wool to digging out gravel for use in construction. Later in his life in

1902, he was asked in a court of law “what is your business?” He replied, “I have cattle, sheep,

and farming.”21 Throughout his storied life, Jacks was always finding ways to expand his busi-

ness and sent many requests to others for help in finding suitable tenants and workers.

Perhaps one of the most lasting effects of Jacks influence was his support of the local

railroad. He invested significantly in this business and was important to the completion of the

first narrow gauge railroad in the state which ran along the Monterey Bay. He invested approxi-

mately $71,000 in the Monterey and Salinas Valley Railroad, completed in 1874.22 His primary

motivation for this was to expand the market for his crops.

A mark of David Jacks was his determination to see things through, exacerbated by his

monetary means to do so. He was first exposed to the local government as the city treasurer in

1852, which led him to access other influential politicians later in his career. His connections as-

sisted in the passage of laws and legislation adhering to his best interests. Through this lens,

David Jacks can be described as an entrepreneur, or as a cut-throat land baron. He utilized oppor-

tunities to his advantage, while staying within the law. Jacks always knew how to appear operate

within legality, but for his tenants whom he foreclosed upon, he was described by them angrily

21 Testimony and Proceedings in the Case of the People vs K.M. Hennekin, December 10th and 11th 1902. David Jacks Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino, California.22 Arthur Eugene Bestor Jr., David Jacks of Monterey, and Lee L. Jacks his daughter. (Stanford University Press, 1945), 5.

Richter 13

as a thief. Some even argued he should be hanged. The Squatters League of Monterey County,

longtime enemies of Jacks, wrote to him threatening to suspend his “animation between daylight

and hell.”23 This effectively meant they wanted him dead, or at least living in the most miserable

conditions possible.

As an individual, Jacks was very detail oriented. He was a self-taught lawyer who wrote

up his own contracts with the people with whom he conducted business, such as tenants, farmers,

and other businessmen. In addition, he employed many lawyers over the years, reviewed their

work, and even opened his own law library in 1888.24 Jacks was a formidable opponent to

lawyers attacking his land claims and business dealings. In 1902, a man known as Hennekin, a

squatter who had just lost in court to Jacks over the ownership of his homestead on one of Jacks’

ranchos, reportedly threatened Jacks at gunpoint. Hennekin allegedly demanded that Jacks sign a

deed to the land or he would kill Jacks. Nothing violent ever occurred between these two men,

and Jacks was never out of step of the law in this situation.

To Jacks, business was business and personal strife and grudges did not qualify as a com-

ponent of legal action. Jacks was not always a shrewd businessman, there was a religious and fa-

milial side to him. In 1861, he married Maria Cristina Soledad Romie. Over the course of his

life, he was father to three daughters and two sons: Janet, Louise Lee, William, Mary R., Mar-

garet A., Romie C., and Vida G.25 Jacks’ religious upbringing carried over into his later life. A

devout Presbyterian, he was the founder of the Presbyterian Pacific Grove Retreat, and donated

to the construction of the original Methodist Church of Monterey.26 His donations to education

included several colleges, which included the University of the Pacific. Jacks played his philan-

23 Executive Committee of the Squatters League of Monterey County to Mr. David Jacks, October 4th 1872. David Jacks Collection, Green Library Special Collections, Stanford University.24 Mrs. Cutter to David Jacks, May 9th 1888. David Jacks Collection, Huntington Library.25 Barrows, 246.26 Bestor, 22.

Richter 14

thropic dealings wisely, often aiding not only the recipient of his wealth, but also his business.

When anti-Chinese protests from the Kearneyites27 in the 1870s threatened immigrant workers in

the area, Jacks stepped forward to provide monetary and legal aid to the struggling Chinese. Al-

though this act appears to be of good will, it also can be seen as a strategy to maintain and grow

his business. He was involved in growing mustard seed. His farm was reported to be one of the

best at mustard seed production in California. At this time the Chinese were considered to be the

experts on the growth and cultivation of mustard seed. Jacks utilized their expertise due in part to

how they lived as tenants and workers. Chinese were numerous in the state and county at this

time. David Jacks appreciated them for their professionalism, especially their punctuality with

paying rent.28

Most importantly to Jacks, Chinese were a cheap labor force who provided excellent and

consistent work. Because of this, Jacks held the Chinese in high regard and respected them.

Jacks's relationship with the Chinese was more than just business. Because of the anti-Chinese

animosity during the late nineteenth century, Jacks often looked out for them, for example, he of-

ten told his workers when it was unsafe to venture into town. One of the greatest reasons Jacks

and his contemporaries preferred to do business with the Chinese was because they were a labor

force that did not mind wage disparity as long as they were steadily employed. Attempting to

minimize his costs, Jacks solicited help from newly arrived Chinese immigrants and offered

them consistent work for a low wage. Lum Sam, a contractor in San Francisco, on July 20, 1882,

Jacks showed his interest:

Your favor of the 15th instant is received. What I want

27 Followers of Denis Kearney, who formed the Workingmen's party of California in 1877.28 Sondra L. Gould Spencer. David Jacks: The Letter of the Law. (California State University, Fullerton, 1992), 33.

Richter 15

is three or four hard workers, chinamen that have not

been in the country long and are willing to work hard,

at a very reasonable price, as I cannot afford to pay

much for such work.29

David Jacks spent most of business life developing his vast amounts of land. His land

covered large swaths of the county, from farmland in the Salinas Valley, to lots in the city of

Monterey, and all of present-day Pebble Beach and Cypress Point.30 The Monterey Californian

reported in 1897 that his landholdings included more than 67,000 acres, most situated in Mon-

terey County. According to the Monterey Californian,

It will interest our readers to know how much land is held in this county by David Jacks.

The table given below is made up from St. John Cox's Map of Monterey County, issued

last year: Moss Landing (Monterey city lands), 110 acres; Monterey city lands (tract

No.1), 28,323.25 acres; Monterey city lands (tract No.2), 2,431.40 acres; Punta de Pinos

rancho, 2,666.31 acres; El Pescadero rancho, 4,426.46 acres; Aquajito rancho, 3,322.56

acres; Saucito rancho, 2,211.65 acres; Pilarcitos rancho (acreage not given); Chualar ran-

cho, 8,880.68 acres; Zanjones rancho, 6,714.49; Los Coches rancho, 8,794.02. Total

67,889.82. The above acreage is equal to 106.07 square miles, and does not include his

interest in the Ashley estate, nor 200 acres of the Milton Little property, nor the Pillarci-

tos Rancho, nor town lots in Monterey, nor——everything else he claims in the county--

29 David Jacks to Lum Sam, July 20th 1882. David Jacks Collection, Huntington Library.30 Sandy Lyndon, Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. (Capitola, California: The Capitola Book Company, 1985), 142.

Richter 16

and he claims every piece of land that adjoins what he has recorded, according to popu-

lar report.31

Unfortunately, since many of Jacks's landholdings were contained within former Spanish

land grants, some of the titles were up for debate and challenged for many years. His largest title,

29,698.53 acres, known as the Monterey City Lands carried over from the pueblo days, was chal-

lenged all the way up to the United States Supreme Court. Jacks and his associate Delos R. Ash-

ley, purchased the old pueblo lands at a Sheriff's sale in 1859. This land was contested by the

City of Monterey for 57 years until 1906 when the Supreme Court settled in Jacks’ favor. The

case of the City of Monterey v. David Jacks (1906) questioned the true land ownership. The long,

drawn out litigation process did not prevent Jacks from becoming the largest and most powerful

land owner in Monterey County. His abundance of land dramatically influenced the development

of the surrounding region. His determination to see this battle through never prevented him from

reaching his goals. He used his economic and political influence to negotiate the waters of legal

battle.

31 Jacks Territory. Monterey Californian, April 1st 1879.

Richter 17

Pueblo Land and the Supreme Court

Mr. David Jack - Sir:

Nearly four years have we waited for a decision in the Chualar case in order to arrive at a

decision in your case. Now that this case has been decided in favor of the squatter on that

land which you pretended to claim as a part of the Chualar Grant and you have there by

been the cause of great deal of unnecessary annoyance and expense to those settlers —

some of them you have actually sued for trespass and damages, putting that said suit was

damage at $1500 at the time that said suit was brought with an additional $100 per

month for every month that they occupied that land there after. Now you low lifed Son

of Bitch you have sued them for that amount of damage - to you - for occupying United

States government land that happened to join your grant land. Now you Son of a bitch if

you don’t make good that amount of damage to each and every one of those settlers

which you sued as well as a reasonable amount for compensation to each of the other

settlers — if you don’t do this inside of ten days you son of a bitch — we shall suspend

your animation between daylight and hell.

By Order of the Executive Committee of the Squatters League of Monterey County 32

It is obvious here that the Squatters League of Monterey County were quite unsatisfied

with regards to how the land of Monterey was divided up after the signing of the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The administration put into place during this period made the Squat-

ters League furious because of the mishandling, in their view, of land claims, grants, and titles.

32 Executive Committee of the Squatters League of Monterey County to Mr. David Jacks, October 4th 1872. David Jacks Collection, Green Library Special Collections, Stanford University.

Richter 18

The major concern here was of the selling of former Mexican lands claims, ranging in size from

less than an acre to over 1.75 million acres.33 The cause for dispute over this type of land was be-

cause of poor documentation as a result of limited surveying. In addition, the larger ranchos were

poorly marked, and used mostly for animal grazing despite their potential as farmland. Squatters

were often confused because they thought they were homesteading on public land, which in fact

was on rancho property. Squatters included gold miners and other opportunists wanting early ac-

cess to free land.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the US government increased the encourage-

ment the development of land nationwide. This led many to head west and acquire land, legally

or otherwise. Squatters were a common problem encountered by land developers such as David

Jacks. Squatters often chose unmarked spot to live on, hoping that they might inherit it somehow.

Jacks was ahead of the competition because he acquired land by purchasing it, renting it, and

then foreclosing. Conflict was common between entrepreneurs like Jacks and people who ac-

quired land by squatting, which often resulted in them feeling cheated. Jacks capitalized on this

strategy to procure his land. He operated as a money lender quick to foreclose when payments

from tenants were missed. Jacks dealt with squatters by making them sign leases to be on his

land, with the stipulation that land tenants could not dispute the landlords title to the land. Jacks

was able to make money off of the squatters on his land, and could also evict them as squatters if

they did not pay him on time. Jacks dealt with not only individuals, but also municipalities and

other groups. It was in these situations that the disputes became a drawn out process. The most

famous example is the battle between Jacks and the City of Monterey regarding pueblo lands,

which was fought for 57 years until the Supreme Court settled it.

33 Paul W. Gates, California Ranchos and Farms 1846-1862. (Wisconsin: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1967), xix.

Richter 19

The California Land Act of 1851was what gave David Jacks the ability to purchase for-

mer Mexican pueblo lands and develop them to his benefit. This act established guidelines for

land claimants to follow in order to acquire land patents. The guidelines state that applicants

must go to the Board of Trustees for approval. Jacks, an opportunist, bought the Monterey

Pueblo lands with his partner, Delos Ashley, in 1859. Jacks was the acting Treasurer of the

Board of Trustees. Ashley was also a member and former president of the Board of Trustees.

This partnership found them both in a unique position to make money, through their position in

the Board of Trustees and their desire to strike it rich. Before the pueblo lands could be surveyed

completely, Jacks and Ashley, bought the land legally. Ashley represented this claim in court as

he and Jacks’ attorney. This process was a legal move because Jacks, as city treasurer on the

Board of Trustees, needed the funds to pay Ashley his attorney expenses. In order to do so, they

valued the attorney expenses as the same amount of worth of the Pueblo lands at $991.50.34

Therefore, the City of Monterey owed a $991.50 debt to David Jacks, which it paid in the form

of the Pueblo lands.

A new and hostile Board of Trustees that felt cheated by Jacks and Ashley was estab-

lished in 1865. This sparked a conflict between the Board and Jacks and Ashley which proceeded

all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Ashley left this battle in 1869 and gave all of his

holdings to Jacks. Ashley grew tired of this battle, and conveyed all of his interest in the pueblo

matters to Jacks in 1869 for $500, which was the same amount he invested before the deal oc-

curred. The new Board of Trustees claimed that the transaction that Jacks had implemented was

illegal. Ashley was no longer in Monterey before the new board pressed this matter.

34 Sondra L. Gould Spencer. David Jacks: The Letter of the Law. (California State University, Fullerton, 1992), 55.

Richter 20

The Board of Trustees continued the effort to gain control of the pueblo lands. Due to the

lack of funding, their efforts never impacted Jacks. Eventually, by 1877, Robert Forbes, the at-

torney for the City of Monterey, offered to help reclaim the pueblo land from Jacks if he was

able to obtain fifty percent of the recovered property. In order to do so, the Board and Forbes had

to obtain a patent to the pueblo lands. In response, Jacks’ strategy was to draw out the process of

getting a patent as long as possible. This issue brought up the question of the legitimacy of titles

in the entire city of Monterey. Most land owning citizens did not make an effort to find out the

truth of the history of their land. An example of this predicament in action is the agreement be-

tween the Board of Trustees and the Pacific Improvement Company. The Pacific Improvement

Company bought land, that became the future location of the Del Monte Hotel, and later the

Naval Postgraduate School, from David Jacks. Because the the US Navy now occupied the land,

the Board agreed not to attempt to reacquire their land if the courts ruled in their favor.35

Overall, this litigation process slowed the development of Monterey and enraged other

landholder wanting to transfer their holdings. Ten years passed until the first official response to

Forbes' application. The California Legislature did issue the patent to Forbes. However, David

Jacks was still the lawful owner of these lands. In 1891 and 1896, the city filed formal com-

plaints against Jacks to the Superior Court. Jacks denied all claims that the city made. The Supe-

rior Court decided on both complaints in favor of Jacks. The city then claimed to the Supreme

Court of California that the Board of Trustees which issued Jacks the lands initially in 1856 were

not legitimate and therefore could not convey the land. At that point, the transaction occurred al-

most 50 years prior. Dissatisfied with the ruling, the city of Monterey appealed their case to the

US Supreme Court. Potentially, a decision by the court could nullify all previous transactions.

35 City of Monterey. “Minutes of Decision Bodies,” Volume I, January 1850 to December 1885 and Volume 2, June 1887 to May 1897.

Richter 21

Still, the verdict came out in favor of Jacks.36 During this time, he developed his land and de-

fended his titles. Finally, the California Supreme Court upheld all of the landholdings to Jacks,

and further found him innocent of any crime in 190637. It is evident that Jacks, from the begin-

ning, was able to navigate this transaction legally, and provided no evidence of wrongdoing

throughout.

36 Sondra L. Gould Spencer. David Jacks: The Letter of the Law. (California State University, Fullerton, 1992), 60.37 City of Monterey v. Jacks (1906). December 3rd, 1906.

Richter 22

Social Theory: Land Tenure

The land acquisition of David Jacks will be analyzed within the context of social theory.

The evolution of property rights and their effects on resource allocation can be traced back to en-

trepreneurs like David Jacks in the mid to late 19th century. David Jack often leased his land to a

tenant who would establish farms, often taking place in the Salinas Valley of California. By ana-

lyzing theory to explain land tenure, a better understanding of David Jacks’ methods of acquiring

land can be made.

In the 19th century monopolization of land came to fruition. By looking at the history of

how land was acquired during that time, along with little to no regulation, monopolization was

common. An industry important to this matter in California is agriculture. In order for agriculture

to work, land must be owned and be able to farmed. Within California, renting land to tenants is

prevalent in the agriculture industry. David Jacks was known for his leasing of land for this pur-

pose.

Mexican land grants are a major contributing factor, if not the principal factor, for the

mess of land regulation in early California. The Mexican land policy worked well when Califor-

nia was sparsely populated and pastoral. Cattle raising in this region before American occupation

was the main business for Mexican land owners. When a citizen settled land in Mexican Califor-

nia, the Mexican government issued a town lot to them. Likewise, if a citizen who wanted to

raise cattle, a range of land was offered to them by the Mexican government. These claims were

often not very detailed and little or no documentation proved their existence by the time Califor-

nia became a part of the United States. When California was ceded to the United States by Mex-

ico following the Mexican-American was in 1848, the rights of the land holders to their claims

were carried over. Looking back at this time, it was not a wise decision to carry over these land

Richter 23

claims without question. Instead it would have been better to allow the land grant holders to keep

a certain amount of their land, and define the surrounding area around their land as a part of pub-

lic domain. These lands and who owned them were vaguely defined, which caused a whole lot of

strife for both land owners, tenants, and future residents, as shown in the case of David Jacks.

Once the new settlers in California began to establish farms, cultivate land, and make im-

provements, the old land grants began to float. Float in this context means that once a settler

built his farm, a land shark, who bought out the indigenous Californian from the Mexican days,

declared that the settler was on his land as part of the original Mexican grant. The settlers often

claimed this land because they thought it was a part of government land. Due to the ambiguity of

old Mexican land grants, entrepreneurs and land sharks were often successful in claim the sur-

rounding settled land as their own. This process often led to monopolization of areas by individ-

ual entrepreneurs. It is debatable whether Jacks was a monopolizer, but his business practices

were condemned by many. Perhaps his actions can best be synthesized by way of a land tenure

theory.

Land tenure is a theory outlining the conditions in which people occupy land. At its core,

it states that the behavior of people affects conditions of land such as property, a place of in-

come, and a place residence. Because people visualize their own individual future, the land ten-

ure system is expected to help achieve their goals. Within the condition of tenure, especially in

the 19th century, farmers were among the largest of groups affected by these conditions. Farmers

seek land to provide them with income, to be profitable over time, as a place to raise a family,

and have security.

Regarding Jacks individual situation with his farming business, as specific land tenure

theory can be applied. The Farm Business Theory of Tenure as discussed by agricultural econo-

Richter 24

mist Rainer Schickele. In his review of theory, Schickele outlines the conditions in which land

tenure and a farm business operate. Firstly, the business of farming is to be conducted in accor-

dance with the financial, organizational, and managerial principles that other non-farming busi-

ness operate. Secondly, the free market forces are allowed to determine the tenure status, size of

farm, and family income for each person who works on the farm, from farmer to employer, ac-

cording to their ability to work within the market. Lastly, farmers do receive the same legislative

protection of other producers elsewhere in the economy.38

Under these guidelines, entrepreneurship is a way to increase productivity. Land tenure

theories can be applied to land owners as well. In the case of David Jacks, he sought to freely

buy and sell land without restriction. David Jacks was an entrepreneur that valued holding and

developing his land. Because he was quick to foreclose on those who did not pay rent on time, he

wanted to minimize the money he had lost by finding a new tenant. In addition, he wanted to be

able to have a steady source of income from his tenants. For Jacks, he rented his land most often

to immigrants, such as the Chinese. Jacks described the Chinese as being a very reliable labor

force to work and live on his land. Perhaps most importantly, they accepted low wages for the

quality of work they provided on his agricultural land. For Jacks, this situation was an excellent

business opportunity.

Before the theory can be applied, Jacks relationship with the Chinese needs to be dis-

cussed. During the time that the Chinese were immigrating to California, David Jacks was at

work developing his land and defending himself in various court cases .The Chinese were a

blessing for the business of David Jacks. Because his largest parcel, that of the Monterey Pueblo

Lands, could not be improved upon until the court case was settled, he needed a labor force to

38 Rainer Schickele. "Theories concerning Land Tenure." Journal of Farm Economics 34, 5 (1952): 738.

Richter 25

work his vast array of other properties. He would recruit Chinese renters, from established work-

ers to novice immigrants. He maintained strong connections with the Chinese, showed them

trust, and went out of his way on a few occasions to keep his relationship strong, a relationship

marked by mutual trust.39 Despite anti-Chinese sentiment in much of California, at the time they

were generally accepted in agricultural areas. The Chinese made significant contributions to agri-

culture in Monterey County and were valued by farm owners as a result. For example, the Chi-

nese established the sugar beet industry in California in the community of Watsonville, and also

converted wild mustard into a profitable crop. Mustard seed became a booming industry, and by

1876, approximately 200 tons were being shipped from the Salinas Valley annually.40 David

Jacks cultivated mustard on his land with the help of the Chinese. The Chinese earned respect as

workers, earning their living as “truck gardeners, tenant farmers, owner-operators, commission

merchants, fruit packers, harvest laborers, and farm cooks.”41 Overall, the Chinese were an inte-

gral component of David Jacks’ farming business.

39 Sondra L. Gould Spencer. David Jacks: The Letter of the Law. (California State University, Fullerton, 1992), 60.40 “The Mustard Trade.” Salinas Index. 1876.41 Sandy Lyndon, Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. (Capitola, California. Capitola Book Company, 1985), 62

Richter 26

Conclusion: Habitus

A social theory to understand David Jacks is the theory of Habitus, by Pierre Bourdieu.

This concept is essential understanding how external social structures influence the internal

thought processes, decisions, and personality of individuals. By looking at this theory, David

Jacks’ decisions can be analyzed and a conclusion can be reached.

Habitus is defined by Bourdieu as a type of social structure which organizes the the

thoughts and practices of individuals, unique to that individual.42 Habitus is the mental system of

structures within a person, created to represent the external structures around them. These inter-

nal structures are unique to each individual person even if they represent an external structure

which is well known to many others. Habitus is thoughts, beliefs, preferences, interests and the

general understanding of the world. The process of socialization, especially early family life and

education, creates habitus within a person. Bourdieu asserts that habitus has the power to influ-

ence individual actions of a person, and to construct the social word a person finds themselves

within. The internal and external worlds that are a part of habitus are viewed as intertwined

spheres of understanding, because the person changes over time due to factors such as aging or

parenthood. According to Bourdieu, there are four types of social capital which influences the in-

dividual decision-making process. Here, the habitus of David Jacks can be explained.

The first type of capital is social capital. This form of capital is defined as the circles of

friends, groups, and memberships one finds themselves within.43 Jacks was a man with many

connections. Since early in his career, he had a great amount of colleagues, as well as enemies.

Jacks is a social man who values those around him, mostly for his benefit. He maintained close

42 McGee, R. Jon, and Richard L. Warms. Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History. Lan-ham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. 596-597.43 Ibid, 581.

Richter 27

relationships in order to gain more wealth and power, especially in situations regarding legal bat-

tles.

The second type of capital is cultural capital. This type of capital is defined as an individ-

ual’s knowledge and experience as part of a community, as well as occupation.44 Jacks had a

deep sense of community in the city of Monterey. He was one of the richest men in the whole re-

gion who was a well-known public figure due to his business operations. This made his cultural

form of unique, and he was known as a philanthropist to some, and a cut-throat business man to

many. In his work, he was the boss. He had many people who worked for him which gave him

utmost mobility in his craft. His interactions with the Chinese helped him create an image of a

fair landlord and boss, even if he was motivated by the selfish desire to become more wealthy at

the expense of his tenants.

The third variation of capital is economic capital. All of a person’s economic assets are

included in this capital.45 Property owned and earning ability plays a critical role in this form of

capital. Perhaps in this form of capital Jacks stands out the most. He was a man of great wealth

due to the amount of property he owned. This most likely gave him an overinflated sense of su-

periority which aided in the competitiveness of his business with others looking to undermine his

interests.

Lastly, symbolic capital is defined as the prestige that one earns due to the way the indi-

vidual lives their life.46 Keeping all of the other forms of capital in mind, it is safe to say that

Jacks was rich in symbolic capital. He was a prominent figure that became rich due to the way he

used his large amount of land. He was made more famous after local mountain to the city of

Monterey, Jacks Peak, was named after him, as well as a type of cheese, Monterey Jack. His true

44 Ibid.45 Ibid.46 Ibid.

Richter 28

claim to fame was his shrewd business practices which are not always looked upon as a benefit

for his character. It is because of his business practices that he is best remembered as notorious

land baron, as opposed to the image of a philanthropist which he tried to cultivate.

Richter 29

MethodsThe methodology I used for this project is historical methodology. Historical methodol-ogy involves conducting primary and secondary source research to gather evidence. After criti-cally analyzing the information I have found, I historically interpreted my findings. I present the research to follow a narrative of history and explain how the topic fits into society. By writing my capstone in a narrative format, change over time is evident. I explored my subject through finding literature at local libraries and archives such as the Monterey Public Library, Colton Hall, and the Monterey County Historical Society. I also analyzed primary source documents like newspapers, government documents, journals, and census records found online. Some primary source documents include government papers on Jacks and his case with the courts in particu-lar, which can be found at Colton Hall, the Monterey Public Library, and the Monterey County Historical Society.

Richter 30

Connection to Service Learning

1. Does your research respond to community-identified needs?

My research does respond to the needs of the community. This semester, I volunteered at

Seaside High School, which sits on the land of a city that was formed out of David Jacks’ old ter-

ritory. I worked as an after school tutor in the subjects of World & Us History, and English liter-

ature and composition. From my interactions with students, not many of them know the history

of their hometown. In addition to teaching them their school related topics, I gave them insights

to the history of the local area which they were excited to learn about. Most of these students

were unaware of the local historical resources, such as the Monterey County Historical Library

and the Monterey Public Library, which is the oldest public library in the state. Therefore my re-

search helped students gain a better understanding of local history, which in turn help them with

understanding how they and their community fit into the world as a whole.

2. How does your social and behavioral science research serve the community?

My research shows that the past events of a powerful land owner, David Jacks, had an

impact on the city which can be seen today. His land purchases and business actions in general

form part of the local legend. He is remembered as a notorious man who was quick to foreclose

on his tenants to make a profit. My application of social and behavioral theory shows that he was

an individual inspired to navigate the most profitable path through life, at the expense of others.

For the current community, this is important to understand because the small, quiet town of

Monterey and the surrounding region was once subject to political drama in the entire second

half of nineteenth century following the statehood of California. This fact is important to under-

Richter 31

stand because political drama still occurs today, and if the community can learn anything from

past events, it is that politics and shady business dealings are a part of society that can be under-

stood and maneuvered through successfully.

3. What does your research teach you about “service” (issues of justice, diversity, compassion

and social responsibility)?

My service has shown me that not everything goes to plan regarding teaching. I have

learned that helping students is a labor of love where I need to show them my passion for the

subject in order to spark their interest in the materiel. This cannot alway be achieved, as many

students are not interested in history and have other school subject with are more important to

them. However, the students that seek the most help are often first generation high school stu-

dents and are the first in their family to apply for college. I see that these students have a desire

to learn, but sometimes just need encouragement from me as a tutor to achieve success. Because

I want to be a teacher later in life, I value this service experience as it has taught me patience,

compassion, perseverance, and humility. I have also learned to hold myself in a more respectable

manner because these students, especially those wanted to pursue a college education, look up to

me as an example to learn from.

4. How does your research increase community capacity?

My research increases community capacity by helping the community understand the

past events which happened on their doorstep. Monterey is one of the oldness establishments in

California, with settlement going back hundreds of years. For many it is interesting and hum-

Richter 32

bling to know of what happened many years ago. The events of the past still affect present day

Monterey and beyond. David Jacks was the original owner of much of the land on the Monterey

Peninsula and Salinas valley, which today are many people’s home and peace of work. If it was

not for Jacks, these places would not exist the way they do today. People lives depend on the his-

tory of this land and my research shows them why.

5. How do you use the knowledge of social science theory and methods to conduct an inquiry

on the historical context and causes of the SL issue that you selected?

I used my knowledge of social science theory and methods to delve into the history of my

subject and come up with results. I have been studying social science theory during my entire

time at CSUMB and this project allowed me to apply it. I was interested in understanding the

way the old social systems apparent in this area developed over time and contributed to the direc-

tion the region took. Specifically, I analyzed the character of David Jacks after I read about him

and his business practices. Using contemporary social theory, I was able to describe the decisions

he made and why. Social theory was applied in this paper to help the reader understand that

through historical analysis, an opinion can be made about a historical figure based on the evi-

dence at hand. Furthermore, I applied what I learned through historical analysis to my service

learning side of this project through teaching students the importance of the historical method in

their studies.

Richter 33

Richter 34

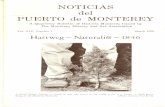

Map of the Pueblo Lands of Monterey47

47 Map of the Pueblo Lands of Monterey. January 1963. Monterey Peninsula Herald.

Richter 35

Bibliography

Barrows, Henry D. Memorial and Biographical History of the Coast Counties of California, Chicago, The Lewis Publishing Company, 1893.

Bestor, Arthur Eugene, Jr. David Jacks of Monterey, and Lee L. Jacks his daughter. Stanford University Press, 1945.

Bob Kohn. "Jacks County." Dr. Hart's Mansion - Pacific Grove, California. 2008.

“The California Cattle Boom, 1849-1862.” Monterey County Historical Society.

City of Monterey v. Jacks (1906). December 3rd, 1906.

City of Monterey. “Minutes of Decision Bodies,” Volume I, January 1850 to December 1885 and Volume 2, June 1887 to May 1897.

Cleland, Robert. The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California, 1850–1880, The Huntington Library, 1975.

David Jacks to Lum Sam, July 20th 1882. David Jacks Collection, Huntington Library.

Executive Committee of the Squatters League of Monterey County to Mr. David Jacks, October 4th 1872. David Jacks Collection, Green Library Special Collections,

Stanford University.

Gates, Paul W. California Ranchos and Farms 1846-1862. Wisconsin: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1967.

Gonzalez, Manuel G. Mexicanos: A History of Mexicans in the United States, Bloomington:Indiana University Press, 2009.

Hackel, Steven W. Junípero Serra: California's Founding Father. New York: Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Haas, Lisbeth. Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769-1936. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Henderson, Timothy. The Mexican Wars for Independence. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2009.

Hurtado, Albert L. Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003.

Jacks Territory. Monterey Californian, April 1st 1879.

Richter 36

Lyndon, Sandy. Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. Capitola, California: The Capitola Book Company, 1985.

Map of the Pueblo Lands of Monterey. January 1963. Monterey Peninsula Herald.

McGee, R. Jon, and Richard L. Warms. Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Miller, Robert Ryal. Juan Alvarado Governor of California, 1836-1842. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1998.

Mrs. Cutter to David Jacks, May 9th 1888. David Jacks Collection, Huntington Library.

“The Mustard Trade.” Salinas Index. 1876.

Neasham, Aubrey. “The Raising of the Flag at Monterey, California, July 7th, 1846.”

Rawls, James J. Indians of California. The Changing Image. University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

Schickele, Rainer. Theories Concerning Land Tenure. Journal of Farm Economics 34, 5. 1952.

“Secularization and the Ranchos.” Monterey County Historical Society.

Spencer, Sondra L. Gould. David Jacks: The Letter of the Law. California State University, Fullerton, 1992.

Stevenson, Robert Luis. The Old Pacific Capital. San Francisco, Colt Press, 1944.

Stone, Virginia, “Who was the real David Jacks?” Noticias del Puerto de Monterey Monterey Historical and Art Association, 1989.

Testimony and Proceedings in the Case of the People vs K.M. Hennekin, December 10th and 11th 1902. David Jacks Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino, Cali-

fornia.

Walton, John. Storied Land: Community and Memory in Monterey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Yenne, Bill. The Missions of California. San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Press, 2004.

Richter 37