rm theory

-

Upload

zaki-ahmed-khisal -

Category

Documents

-

view

116 -

download

0

description

Transcript of rm theory

This open learning pack is designed to help you study and work towards your dissertation and fulfil the learning

objectives for the module.

The dissertation is a piece of research that shows you have the capability to carry out the research process in an

independent and thorough way. It brings together all the research skills that you have developed over the past two or

three years while studying other modules on the degree and enables you to study a topic of your choice in more

depth. We take you through all the stages of the process and give guidance on how to write a research proposal and

the final dissertation. It is designed for you to work through on your own and gives lots of activities for you to

complete. In addition, it is important that you undertake additional investigation into research methods as we can only

give you the basic guidelines here. For example, once you have decided on a particular method to use you will need

to read up on that method in a number of research methods textbooks. Your tutor or supervisor can help you with any

aspects that you find difficult.

The first thing to establish is the nature of the research process. We cover this now.

There is no agreement or consensus between writers on how the word should be defined or interpreted. One reason

for this is that ‘research’ means different things to different people, for example:

Children at school research their local environment.

1. People research the times of trains from Waterloo to Paris.

2. Scientists research the effects of genetically modified food.

3. PhD students research and extend knowledge in their subject area.

A useful starting point in answering the question is to see how research is defined in a dictionary.

Activity I.1

Look up the definition of the word research in a number of dictionaries, such as Collins, Oxford English Dictionary,

Chambers, Websters, Collins Dictionary of Sociology etc.

Dictionary definitions use words such as ‘systematic’, ‘careful’, ‘facts’, ‘information’, and ‘investigation’. However, the

problem with these definitions is they are not sufficiently rigorous or detailed for our purposes. For example, the word

‘information’ is often used when ‘data’ should be used.

From the many definitions offered in research methods textbooks, there is some agreement that research:

is a process of gathering facts (data)

is systematic

reviews, questions and synthesises existing knowledge

involves analysis

possibly increases knowledge

is a combination of all of these

Research is about process (the approach you take) and thinking (questioning, synthesis, analysis, criticality). As

you work through this material, we discuss process and the intellectual activity – thinking.

Three words that occur very regularly in research texts are concept, theory and model. It is often assumed that

everyone knows what these words mean and what the differences between them are. These are usually false

premises. The terms will be defined and briefly discussed. As in most situations there are a number of possible

definitions for each word.

Concept

Simply, a concept is an abstract notion or idea, something that isn’t concrete.

"A word or set of words that expresses a general idea concerning the nature of something or the relations between

things, often providing a category for the classification of phenomena."

Theodorson & Theodorson 1969

In other words a concept is an abstract summary of characteristics that we see as having something in common.

Concepts are created by people for the purpose of communication and efficiency.

A concept has no set meaning and it is up to us to define what we mean by the concept. But if concepts have no set

meaning then anyone can define a concept in any way that they wish. But if everyone can define the concept in any

way they like the concept becomes worthless; unless there is agreement on the meaning communication is

impossible. A concept therefore has to be defined, but in such a way that it has a degree of acceptance. Experts in

the field usually propose such definitions.

As a researcher you would be expected to:

review this range of definitions, and

decide on which you are going to use.

Theory

A very loose meaning of the word is:

That part of the study of a subject which is not practical.

For example, teaching theory is often contrasted with teaching practice.

More substantial definitions of a theory are:

"A theory is a set of interrelated principles and definitions that present a systematic view of phenomena by specifying

relationships among variables with the purpose of explaining natural phenomena."

Kerlinger 1986

"Any set of hypotheses or principles linked by logical or mathematical arguments which is advanced to explain an

area of empirical reality of type of phenomenon."

Jary & Jary 1995

In effect a theory includes a set of basic assumptions and axioms as the foundation and the body of the theory is

composed of logically interrelated, empirically verifiable propositions.

Let us look at one of these theories in more detail.

Motivation theories fall into two main groups – content theories and process theories. Content theories of motivation,

such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Herzberg’s two factor theory of motivation, focus on what motivates people.

Process theories, such as Expectancy theory and Equity theory, place more emphasis on how people become

motivated. If we look at one of these theories, Maslow is based on a set of assumptions and links a number of

variables (physiological, security social, self-esteem and self-satisfaction) to explain motivation. (Torrington and Hall,

1995)

Concepts are generally regarded as being at a lower level of abstraction than a theory but a necessary part of any

theory, since theories are formed from concepts.

Model

Lucey (1991) defines a model of "any simplified abstract of reality ".

For example we are all familiar with scale models of aircraft, cars, ships, housing estates, etc. These simplified

versions of the real thing are called physical or iconic models. They are based directly on the representation of the

phenomenon being studied and look like the object.

An extension of the physical model is the analogue model. These models are physical in form but do not have the

same appearance as the object being investigated. The circular movement of the hands of a wristwatch is an

analogue of the behaviour of time.

However there are other types of models.

Symbolic models are based on logic, and inter-relationships between concepts are usually expressed

mathematically or algebraically. They are concerned with quantification.

Mathematical (algebraic) equations are symbolic models. For instance a simple mathematical model is:

Profit = Revenue minus Total Cost

or P = R – TC

There are many such symbolic models in the fields of economics, finance, statistics, science and engineering. One

approach to the analysis of such models is to represent the model on a spreadsheet and conduct sensitivity analysis.

A conceptual model is composed of a pattern of interrelated concepts but not expressed in mathematical form and

primarily not concerned with quantification. Diagrams, such as maps, graphs, charts, balance sheets, circuit

diagrams, and flowcharts, are often used to represent such models.

Models may be very simple or very complex. Since the world we observe cannot be observed in totality, each model

reflects only a limited aspect of the total world. No single model, or combination of models, reveals the truth of the

structure of reality. Each model reveals and orders reality from a particular perspective.

In practice concepts and especially theories are often referred to as models.

Other words associated with concepts theories and models are law, empirical and variable.

A law is a precise statement of a relationship among facts that has been repeatedly corroborated by scientific

investigation and is generally accepted as accurate by experts in the field. Laws are generally derived from a theory.

A law is frequently referred to as a universal and predictive statement. It is universal in the sense that the stated

relationship is held always to occur under the specified conditions, although the conditions may be predicted to follow.

Empirical means based on experience, observation or experimentation. Empiricism is the belief that all human

knowledge is derived from experience – as opposed to, for example, idealism, rationalism and naturalism.

A variable is a characteristic or attitude that changes or varies. More exactly, it is any measurable characteristic

which can assume varying or different values in successive individuals cases.

In the mathematical sense it is a quantity that may take any one of a specified set of values, for example, height.

A wider use of the term variable includes mathematically non-measurable characteristics such as gender and religion.

It is usual, when comparisons are made between two variables or there is a relationship between two variables, to

term one the dependent variable and the other the independent variable. The independent variable is the variable

that is changed or manipulated. As a consequence of this change there will be a resulting change in the other

variable – dependent variable. For example, research may be conducted into the intensity of lighting in a room in

order to observe the effect on productivity levels of workers. The independent variable is the intensity of lighting and

the dependent variable is the level of production.

The research process or methodology is the approach to the entire study – it is the

master plan. It is the blueprint for achieving your objectives, one of which is the

production of the dissertation. Irrespective of the research you are going to

conduct, there are several fundamental stages you will have to go through. The

diagram below is a simplified, traditional and highly structured view of the

research process.

The diagram shows the systematic nature of the research process. Unfortunately it is not quite so

straightforward as many of the stages overlap and there is much ‘looping back’ to previous stages.

This simplified diagram does not show the underpinning theoretical issues and questions that have

to be addressed. The following diagram shows the different aspects to be considered under each

section.

As you can see each stage in the process has many aspects and issues to be considered. We cover

all of these stages in the units in this pack.

This unit is designed to help you get started in the research process and reach the stage of writing your research

proposal. We begin by looking at the theory of research and the different types of research, the actual research

process, and its outcome. We go through some decision-making stages to help you with your research proposal.

Superficially the research process can appear to be relatively simple - if you carry out the basic steps methodically

and carefully, then you should arrive at useful conclusions. However, the nature of research can be very complex and

when you are reading textbooks on research methodology you will come across many unfamiliar words and terms.

We first look at types of research and explain some of the terms.

Types of research

The main different types of research can be classified by its purpose, its process and its outcome. These can in turn

be broken down further:

The purpose of the research can be classified as:

o exploratory

o descriptive

o analytical

o predictive.

The process of the research can be classified as:

o quantitative

o qualitative.

The outcome of the research can be classified as:

o applied

o basic or pure

o action.

Let us look at these in more detail.

Purpose of research

Exploratory research

This is conducted when there are few or no earlier studies to which references can be made for information.

The aim is to look for patterns, ideas or hypotheses rather than testing or confirming a hypothesis. In

exploratory research the focus is on gaining insights and familiarity with the subject area for more rigorous

investigation later. In an undergraduate dissertation it is likely that you will be drawing on previous studies

and so pure exploratory research is not generally appropriate for studies at this level – it is more appropriate

for postgraduate research. However, it is possible that you may carry out an initial survey to establish areas

of concern (exploratory research) and then research these issues in more depth, perhaps through

interviews, to provide a deeper understanding (explanatory research).

Descriptive research

This describes phenomena as they exist. It is used to identify and obtain information on the characteristics of a

particular issue. It may answer such questions as:

o What is the absentee rate amongst a particular group of workers?

o What are the feelings of workers faced with redundancy?

The data collected are often quantitative, and statistical techniques are usually used to summarise the information.

Descriptive research goes further than exploratory research in examining a problem since it is undertaken to

ascertain and describe the characteristics of the issue. An undergraduate dissertation may include descriptive

research, but it is likely that it will also include one of the following two types (explanatory or predictive) as you are

required in your dissertation to go beyond description and to explain or predict.

Analytical or explanatory research

This is a continuation of descriptive research. The researcher goes beyond merely describing the

characteristics, to analyse and explain why or how something is happening. Thus, analytical research aims

to understand phenomena by discovering and measuring causal relations among them. It may answer

questions such as:

o How can the number of complaints made by customers be reduced?

o How can the absentee rate among employees be reduced?

o Why is the introduction of empowerment seen as a threat by departmental managers?

Predictive research

Predictive research goes further by forecasting the likelihood of a similar situation occurring elsewhere. It aims to

generalise from the analysis by predicting certain phenomena on the basis of hypothesised, general relationships. It

may attempt to answer questions such as:

o Will the introduction of an employee bonus scheme lead to higher levels of productivity?

o What type of packaging will improve our products?

Predictive research provides ‘how’, ‘why’, and ‘where’ answers to current events as well as to similar events in the

future. It is also helpful in situations where ‘What if?’ questions are being asked.

Process of research

There is no consensus about how to conceptualise the actual undertaking of research. There are, however, two main

traditions of approaching a research topic – quantitative and qualitative. Each approach demands different

research methods.

Quantitative research

The quantitative approach usually starts with a theory or a general statement proposing a general

relationship between variables. With this approach it is likely that the researchers will take an objective

position and their approach will be to treat phenomena as hard and real. They will favour methods such as

surveys and experiments, and will attempt to test hypotheses or statements with a view to generalising from

the particular. This approach typically concentrates on measuring or counting and involves collecting and

analysing numerical data and applying statistical tests.

Qualitative research

The alternative tradition is the qualitative approach. Here the investigator views the phenomena to be

investigated as more personal and softer. He or she will use methods such as personal accounts,

unstructured interviews and participant observation to gain an understanding of the underlying reasons and

motivations for peoples’ attitudes, preferences or behaviours. With this approach, the emphasis is more on

generating hypotheses from the data collection rather than testing a hypothesis.

In reading around the subject you will find many alternative names for qualitative and quantitative research.

It is good to have an understanding of these and to recognise them when you see them in research methods

textbooks.

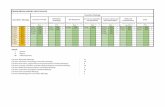

The features and differences between the two research processes are detailed below.

You should note the following points:

Qualitative and quantitative research methods are not clear-cut nor mutually exclusive – most research

draws on both methods.

Both approaches can generate quantitative and qualitative data.

The difference between the two methods is in the overall form and in the emphasis and objectives of the

study.

Outcome of research

Applied research

Applied research is problem-oriented as the research is carried out to solve a specific problem that requires a

decision, for example, the improvement of safety in the workplace, or market research. For your dissertation it is not

usually acceptable to carry out applied research as it is very much limited to one establishment or company and you

are required to look at issues of wider significance, perhaps to your industry as a whole or to a sector of it. You may

have already carried out a problem-based piece of research related to your placement. It is important to understand

that the dissertation requires you to carry out some form of basic research – see below.

Basic research

Basic research is also called fundamental or pure research, and is conducted primarily to improve our

understanding of general issues, without any emphasis on its immediate application. It is regarded as the

most academic form of research since the principal aim is to make a contribution to knowledge, usually for

the general good, rather than to solve a specific problem for one organisation. This may take the form of the

following:

o Discovery – where a totally new idea or explanation emerges from empirical research which may

revolutionise thinking on that particular topic. An example of this would be the Hawthorne

experiments. (Gillespie, 1991)

o Invention – where a new technique or method is created. An example of this would be the

invention of TQM (total quality management).

o Reflection – where an existing theory, technique or group of ideas is re-examined possibly in a

different organisational or social context. For example, to what extent can Herzberg’s theory of

motivation be applied to front-line workers in the contract catering sector?

(Torrington & Hall, 1995)

For an undergraduate dissertation it is most likely that you will be concentrating on reflection, as the scope of the

project is unlikely to be large enough to consider discovery or invention.

Action research

This is a form of research where action is both an outcome and a part of the research. The researcher

‘interferes’ with or changes – deliberately – what is being researched. The critics of action research argue

that since the researcher is changing what is being researched during the process of research, the work

cannot be replicated. If it cannot be replicated its findings cannot be tested in other situations. This prevents

general knowledge being developed and thus it cannot contribute to theory. Also, as the researcher is

involved in the change process there is a loss of critical, detached objectivity. There are two approaches to

action research:

o Classical action research begins with the idea that if you want to understand something you

should try changing it.

o New paradigm research is based on a new model or framework for research. It claims that

research can never be neutral and that even the most static and conventional research exposes

the need for change in what is being researched. It involves inquiry into persons and relations

between persons, and is based on a close relationship between researcher and those being

researched. The research is a mutual activity of a ‘co-ownership’ involving shared power with

respect to the process and the outcomes of the research. Those being researched can, for

example, decide how the research will be undertaken, in what form and with what questions being

asked. The researcher is a member of a ‘community’ and brings to it special skills and expertise.

The researcher does not dictate what will happen. This type of research is most easily carried out

when working with individuals or small groups. It means that the researcher must be highly skilled

not only in research methods but also in the interpersonal skills of facilitating others. It is not,

therefore, usually appropriate for an undergraduate student who is carrying out a major piece of

research for the first time. Action research is often used by educationalists who are trying to

improve their own practice by making changes to the delivery of their classes and by observing and

asking students which actions work best.

As you can see, there are a number of types of research and not all may be suitable for you in your

dissertation. The key points to remember are as follows:

While the purpose of your dissertation may have some elements of exploratory or descriptive research you

should concentrate on research that will mainly fall into the explanatory area, or perhaps predictive research

if you are very confident. Explanatory research gives you the opportunity to demonstrate the skills of

analysis and evaluation which will help you to score highly in your final marks.

The process of your research can either be quantitative or qualitative and the different methods that can

help you to carry out your research in this way are outlined more fully in Unit 3.

It is likely that you will be carrying out basic or pure research in the reflection mode (rather than applied or

action research) as this will give you the best chance of showing that you can test out a theory in a new

situation.

Other research terms

You may find a number of research terms when reading about methodology and it will help if you have some

understanding of them as they can be confusing! The next activity will help you explore some of these terms.

Please do not worry too much if these terms seem confusing at this stage. It will gradually fall into place as you carry

on with this pack and do more reading around the subject. However, we hope this has demonstrated to you that there

is a lot involved in this research process!

A difference between a dissertation and almost any other piece of work is that you have to decide on a topic and the

title. You start with a blank sheet. This, for most students, is daunting, troublesome and challenging. So where do you

begin?

You begin with the ‘research proposal’. This is the document which sets out your initial ideas and thinking and shows,

to a certain extent, how much thinking you have devoted to the issue. The research proposal form specifies the need

for:

topic and title

a research question or hypothesis (not both)

a review of some literature associated with the title

some indication of how you are going to collect the primary data

a time plan

a bibliography of the literature consulted in putting the proposal together.

The key point about any research is that it has to concern something that you are interested in. Motivation in

undertaking research rises and falls. If you have no or little interest to start with, then it will be difficult to lift that

interest should you encounter problems and a drop in motivation later on. In the following sections, we consider each

aspect of the proposal in more detail.

Topic and title

Where does the inspiration for your dissertation topic come from? There are various sources but the most common,

from which this interest may arise, are:

personal experience

something someone has said

something you have read

something you have studied

something you have not studied

your career aspirations.

What is an acceptable topic? Basically any topic is acceptable but:

it must be in the area of your major pathway

it has to be suitable for the level of study

there has to be a literature base which discusses the various theories (concept and model are alternative

words for theory) that underpin your topic.

Start by identifying the general topic area; then have a conversation with yourself that narrows the topic down – to

something that is more focussed – and then come up with main aim or purpose of the dissertation.

If you have more than one topic in mind

Perhaps you have more than one area in mind – if so, you should go through the above process with all of them to

help you decide.

Refining the aim – getting the title

Having stated your aim in one sentence, you now need to think about it in more detail to refine your ideas and

thinking. Hopefully at the end of this you will have a short, succinct title. To do this you need to have a conversation

with yourself. For the example on motivation this conversation may run as follows:

1. Here is how I see the issue. ‘Increased or enhanced motivation leads to increased productivity.’

But what are you referring to when you say ‘increased or enhanced motivation’? What actually happens in

the workplace when motivation is increased? Or put it another way, what causes motivation to be

enhanced? Possible answers are changes in the job design, management or leadership style, organisational

structure or reward system. Why not change your statement?

2. Right! ‘Changes (improvements) in job design, leadership style, organisational structure, reward systems

and so on, cause increased productivity.’

Well, this statement appears to be true, but surely it only happens when the individuals in question have the

ability to carry out the prescribed tasks in ways that are expected. Why not qualify it?

3. OK. ‘Changes (improvements) in job design, leadership style, organisational structure, reward systems and

so on, cause increased productivity when the individuals have the relevant ability (competencies).’

That is better, but by now you should be aware of some of the managerial implications of your chosen line of

research. You can see various new lines of research beginning to open even before you have completed the

design of your research. So, you have now got the flexibility to direct your enquiry along the lines you find

most interesting and appealing.

Why not go back to the original point of focus? Motivation and motivational factors are about individuals and

the outcome of motivation is satisfaction. Since your research idea is on workplace satisfaction your

concerns are with job satisfaction. Why not give this interpretation of the issue?

4. Right. ‘Changes (improvements) in job design, leadership style, organisational structure, reward systems

and so on lead to job satisfaction which causes increased productivity when the individuals have the

relevant ability (competencies).’

That looks even better, but couldn’t you shorten the statement?

5. ‘Job satisfaction causes increased productivity.’

That is short and sweet. What about your conclusion?

6. ‘Increased job satisfaction causes increased productivity, given the right conditions.’

Done!

A nice short title!

Notice the title does not begin with:

‘An investigation into …’

or

‘An analysis of …’

The very fact you are undertaking research implies you are investigating or analysing. Also the title is short – aim for

a maximum of 12 words in your title.

As you can see from this activity, a diverse range of factors determines job satisfaction. There are many examples of

this in the workplace. One example, relating to organisational factors, might be the effects on job satisfaction of a

major hotel rebuilding programme. A feeling of lack of involvement or knowledge of what is happening may lead to a

lot of resentment; moreover, building workers and noise can have a very disruptive effect on the daily work of a busy

hotel.

A dissertation would not cover all of these possibilities. It would probably concentrate on one or two at the most. The

above list shows there are at least 10 potential dissertations in this area. It is important that you narrow down your

topic to a very specific aspect for investigation. You are looking for depth not breadth.

Research questions

Whereas the aim or purpose statement explains the general direction of the study and is summarised by your title,

the research questions (or hypotheses) expand on this by providing detail. This is a critical stage in your research,

even though it appears early in the process.

If you do not ask the appropriate questions you will not be able to collect suitable data and arrive at sensible

conclusions. By research questions we do not mean the detailed questions you might use in interviews or

questionnaires, but questions which identify the general nature of research or issue you wish to focus on.

At the proposal stage we want the core or key question, or, to put it another way, we want a ‘grand tour’ question.

After further reading you might identify another key question, but remember, the more core questions that you have,

the more work you will need to do.

A core research question should imply:

an explanation of some phenomenon

a relationship between variables

a comparison between variables

prediction

analysis.

The types of questions that produce explanations and relationships may begin with:

This list is only for illustrative purposes and is not exhaustive. There are many other possibilities. A point to note, and

one that is often ignored by students, is that a question ends in a question mark.

Another example is:

In the above example, the researcher does not know if there is a difference between younger and older students and

is interested in determining this. However, suppose the researcher knows there is a difference (from other research)

and wants to find out why there is a difference. The aim of the dissertation and main research question will change,

even though the title remains the same.

Hypotheses

An alternative way of posing a research question is to state a hypothesis (plural hypotheses). A hypothesis is a

proposition about the area that you are studying and is expressed as a statement of fact or what you believe to be

true. You then try to find out whether the statement is true or false.

A ‘good’ hypothesis is:

based on current knowledge and understanding (facts, theory)

compares two variables

can be tested by the collection and analysis of data.

A hypothesis is worded such that it implies that the two variables are independent of each other. Strictly this is called

the null hypothesis. If we consider the example on the type of degrees obtained by younger and older students, we

can state the (null) hypothesis as:

There is no difference in the level of degree obtained by younger and older students.

or

Younger and older students do not differ in the level of degree attained.

This hypothesis is then tested by trying to disprove it by saying, ‘let us look for evidence that would show the

hypothesis to be incorrect’. In this example this means trying to show that there is a difference in the level of degree

obtained. If we could find sufficient evidence to show a difference we would reject the null hypothesis:

There is no difference in the level of degree obtained by younger and older students

in favour of the alternative hypothesis:

There is a difference in the level of degree obtained by younger and older students.

Of course, if you show there is a difference it introduces the questions, ‘What is the difference and why?’

The notion of a hypothesis is a difficult one and may not be necessary for your research. However, it is a good

exercise to try to phrase your research in this way as it helps to clarify your ideas.

Another type of hypothesis is a statistical hypothesis. These hypotheses tend to be used when researchers are

dealing with large amounts of numerical data. Also theoretical statistical tests are used to prove or disprove the null

hypothesis. Such hypotheses are unlikely to concern you as you will be handling smaller amounts of data.

Preliminary literature review

For the research proposal, you are required to write an essay that identifies the main underpinning

concepts/theories/models that are relevant to your topic/title/research question. This essay – the preliminary

literature review – is a much smaller version of the actual literature review that would be found in your dissertation,

but provides a starting point that you can use for development.

Primary data collection

As with the literature review you are being asked in the proposal to do something that you have not yet covered in

great detail. In particular, you have to try to identify how you are going to collect your primary data.

Time planning

You have now thought and written about the:

title

core research question or hypothesis

preliminary literature review and bibliography

primary data collection

The penultimate stage of the proposal is to produce a time plan of what you are going to do and when. The plan

should be detailed and include all the tasks necessary to complete your dissertation. Remember these are not

discrete – many of the tasks have to be thought about in advance and overlap with other activities. They also take a

lot longer than you actually think. For example, it is no good thinking that the literature review will take four weeks.

You have to spend time finding material, reading the material, writing a draft, submitting it to your supervisor, giving

him or her time to read it, get feedback, and redraft based on the comments.

Students often underestimate how long data analysis and evaluation takes. At undergraduate level it should take a

minimum of four weeks. Many students, because of poor planning, or things going, wrong find themselves short of

time towards the end of the dissertation and rush the analysis and evaluation. This often negates all the good work

that may have gone before.

A number of approaches are possible in preparing a time plan. The basic method is to list the weeks from the

commencement of the dissertation to the submission and slot in the detail. In this way you can identify holidays and

other times when you may not be able to work on the dissertation. You can also identify milestones and key dates.

Assessment of the proposal

By now you have almost completed the proposal. The final step is to reflect on your proposal. You probably are very

tempted to put in the final full stop and not look at it again! However, you need to reflect and re-assess what you have

written.

Remember that you have to convince the supervisors who assess your proposal that you know what you are talking

about, that you have given sufficient thought to the proposal and that you have devoted some effort to it. To do this,

you need to ask the same questions the supervisors ask when assessing your proposal:

Is the title clear and concise?

Is the core research question appropriate and answerable?

Does the preliminary literature review draw on authors from both textbooks and journals?

o Is it up-to-date?

o Is it sufficiently detailed?

o Is it descriptive or does it include discussion and debate?

o Is it written in a fluent, easy-to-read style?

Is the proposed primary data collection reasonable at this stage?

Is the time plan detailed and feasible?

Is the bibliography correct?

Has the proposal been spell-checked? Is it grammatically correct?

Does it look professional?

Hand in the proposal. Well done!

The literature review is a key part of your dissertation and it is your chance to show that you

have the skills of academic writing appropriate for an honours graduate. You should have used

all these skills before in your earlier studies but the dissertation takes the skills of reading and

writing to a higher level than you have achieved before. In this unit, we help you develop your

academic skills to the level required. These skills are: searching the literature; record keeping;

reading the literature critically; making notes; writing a literature review; referencing and

compiling a bibliography.

Searching the literature is the starting point of all research and is the process of exploring all sources of published

information. This information, whether it is textual, statistical or diagrammatic, is secondary. Searching the literature

will enable you to:

ascertain what has been published and by whom

increase your knowledge and understanding of the topic

assess whether the research topic is feasible

possibly narrow the topic down

refine or amend the research questions

give you some ideas about the approaches, methods and analysis.

Getting started

You should aim to start your literature search as soon as possible. Everything associated with research takes longer

than planned and searching the literature is no exception. At the very outset, you need to undertake the following:

Define the scope of the research and set parameters, for example, by time, geography, industry, or sector of

an industry. The more precise you can be the easier the task. Try and identify key words; include alternative

spellings of these words or synonyms (words that have similar meanings). For example, if you are

researching 'wage bargaining' you should also look at 'industrial relations' and 'conflict theory'.

Conduct searches on these key words using a variety of sources. Only collect articles and books, etc., which

are relevant, for example, in terms of subject matter, methodology, theoretical discussion, research

instruments, etc

Having found one reference in one source, use the references in that to guide you to others. It is important

to try and get the most recent literature first and work back in time.

Sources of published information

Most students underestimate the number of sources and the amount of material available. The basic problems are:

knowing what is available

where to find it.

We can classify sources as:

paper-based sources - books, journals, periodicals, abstracts, indexes, directories, research reports,

conference papers, market reports, annual reports, organisations' internal records, newspapers, and

magazines

electronic sources - on-line databases, Internet, off-line databases (CD-ROMs), videos and broadcasts.

Technical skills

To find the appropriate information, the researcher needs many technical skills. Consider the following:

Do you know the Dewey classification system?

Can you access data from on-line databases?

Can you access data from off-line databases?

Do you know what government publications are held in your university library?

What market intelligence reports are there?

etc.

It is fundamentally important that you keep a record of the details of any text you read, whether it is a book, article or

information on the Internet. Should you wish to return to the material some time later you will know where to look.

Finding information is hard enough, finding it again is even harder!

Keeping a record of a text you have read can be done in a variety of ways - using loose sheets of paper, a notebook,

index cards, or electronically with a spreadsheet, database or even a personal organiser.

Index cards

One way of keeping a record is to build a card index system. It has the following advantages:

They are easy to sort, for example, into topic areas, alphabetical order, etc.

They can be colour-coded, for example, by subject.

You can insert cards as you read more.

You can carry them around with you.

They stand up to wear and tear.

You can check texts and information as you find it.

You are building a bibliography as you go; you will need this eventually and thus ultimately saves time.

Having found a text, note the following basic details immediately on the card:

1. Book or article title.

2. Author's surname and forename and any subsequent initials.

3. Year of publication.

4. If a book: book title, edition if 2nd, 3rd, etc., place of publication, publisher, chapter or page numbers.

5. If an article: the article's title, journal name, volume number, issue or part number, page numbers.

6. Library catalogue number (Dewey decimal number).

7. Precise details when found, also location, floor, room and shelf.

Example

The completed front of index cards for a book and an article in a journal are shown below.

Book/journal:

Book

Author:

Kerlinger, F.N.

Date:

1986

Title:

Foundations of Behavioural Research

Edition:

3rd

Place:

London

Publisher:

CBS Publishing, Japan

Location:

St Mary's Road LRC

Floor A3, Shelf 4

Date found:

20 October 1999

Classification number:

150.72/KER

Book/journal:

Journal

Author:

Brown, M.

Date:

1996

Article title:

Environmental policy in the hotel sector

Journal title:

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume/Number:

Vol. 8, No. 3

Page numbers:

18-23

Location:

St Mary's Road LRC

Floor B2, Periodicals

Date found:

20 October 1999

The SQ3R strategy, which stands for:

is an approach not just for reading a text but for reading a text effectively, efficiently and critically. It has been found to

be particularly useful because it can be applied to different texts (for example, textbook, article or dissertation) and

the type of reading required (for example, overview of the text or detailed reading).

Survey

Most people who are given a new book start reading the text without making any attempt to gain an overview of

whether the book or article is worth spending time on. It is important to survey the whole before you attempt to read

the parts. Here are a few suggestions about how you should gain this overview. To begin with, consider the start and

the end of the book:

Title page - This can give the answer to some important questions: the general subject area, the level of

approach, the author's name and qualifications, the year of publication.

Table of contents - This gives you information about the scope of the book, the way it is organised, and the

main chapters and sections. It is a very valuable source of information in signposting the issues raised.

Preface - The preface, author's remarks, foreword or introduction, will often give you an overview of the

author's intentions and assumptions. This can be particularly valuable when there are different views about

a topic.

Index - Turn to the back of the book and glance through the index; this can give a more detailed source of

information about the book. It is particularly useful if you are looking for references on a specific topic.

Bibliography - Is there a bibliography (some texts call it References)? How many references are given?

Many or few?

Glossary - Is there a list defining key words used in the text? Would it be useful to know any definitions

before you start reading?

Appendices - Are there any appendices? Consider when these might be useful?

Leaf through the book - Turn each page, looking at section headings, any chapter summaries or key

words. Any pictures or figures and tables can be useful.

First and last chapters - For a journal article especially, it is useful to read the first and last paragraphs.

Often these will summarise the key points made. Some of the better textbooks will have chapter summaries

or a list of key points or concepts developed. Headings and sub-headings are also valuable in setting the

scene.

Surveying a chapter - Having gained an overview of the book, you may wish to look at one chapter in

greater depth. Even if you are just dipping into a particular chapter in preparation for a tutorial you should

adopt the same approach.

This survey should take no more than 10 minutes. Investing in this time pays good dividends. You will find that with

practice even a few minutes will give you an overall idea of the content and layout.

Question

The survey process will have helped you to develop further the questions that you want answered. Never start

detailed reading until you have some clear questions requiring an answer. Questioning is a vital stage in assisting

with recall. These questions will vary according to your tasks, but some issues are probably common.

Example

How does this text fit in with what I already know?

Who is telling me this?

Does the author offer evidence to support or contradict the views being presented? Is the piece being

argued from only one point of view?

Is the language used reasoned and objective? Or is it emotive?

What theoretical perspectives does the author apply?

Is the material up-to-date?

What can I do with the information?

The key point is that questioning helps you to read with a purpose. It helps you to be aware of the issues being

discussed.

Read

Reading in detail is the third step - it is not, as many students seem to think, the one and only stage! In planning your

reading remember some key points:

Reading with purpose is more effective than reading without purpose.

Make reading an active process - in other words, you are actively in search of information.

Divide your reading into manageable sections. Do not try and read too much at once.

Make notes after you have read a particular section. Do not try and make notes as you go. This interferes

with your ability to question and concentrate.

Look for the idea behind each paragraph. There should be one sentence in the paragraph that sums up the

key idea.

Look for the author's plan. What is the main idea? How does the author develop the idea behind the book,

through the chapters, sections and paragraphs?

Read the passage again - you may find it easier to return to the book the next day. Difficult concepts will

then appear less difficult. Do not expect to understand everything on the first reading.

Recall

With the SQ3R method, studying does not end with reading the text. You may understand the text, but will you be

able to recall it? Most people forget 50% of a book within seconds of putting it down!

Organised recall strategies will improve your learning in a number of ways:

You will concentrate because you have a task ahead of you.

You can correct memory lapses, thereby making your learning more effective.

You will be active during the learning process. Again, this will make you much more effective.

The key recall steps are:

Depending on the text, try to recall the key points made by each paragraph within a section, preferably in

your own words.

Jot down the key words.

It can be useful to try and recall the main explanatory sentence in each paragraph.

Review

Always check the accuracy of what you recall by viewing again the material you have studied. The best way of doing

this is to repeat the process - survey, question, re-read, recall.

There are two particular aspects to take into account in note making:

1. What are the contents of the notes?

2. Where do you record the notes?

Contents of the notes

It is up to you what you record and the depth or detail contained in your notes. You can record key words, chapter

headings, a summary (which may be provided in the text), quotations, personal opinions, etc. For example, the

following is a 62-word summary of a book written by Carl Boggs in 1980 called Gramsci's Marxism.

"Straightforward introduction. Easy to read, logical in its structure and presentation of Gramsci's work. Well articulated

background of Marxism and the philosophy of Praxis. Excellent in accessing the notion of ideological hegemony and

its role in the class struggle. Makes Gramsci and his work understandable and applicable to modern capitalism by

taking the key concepts and exploring and applying them in context."

Where do you keep the notes?

Some possibilities of the place where you keep your notes include the following:

1. Use the reverse side of the index card if the comments are short.

2. Use loose sheets of paper, a notebook, or a photocopy of the material. Whichever of these you use you

should cross-reference to the index card.

3. If you use notebooks or paper, do not write on the reverse side as you may wish to cut it up and re-order the

material, for example, topic-by-topic.

4. On photocopies you can use a highlighter pen for key words, sentences, quotations, etc.

You have to do this twice - once in your proposal and once in your final dissertation. In your proposal, the literature

review is rather like an essay and should discuss the key points of relevant literature that you have found on the topic

identified in your title. This section is likely to form the bulk of the proposal, and the committee will be looking for

evidence that you have found some key and relevant texts in the topic area, have read them, identified some key

themes and issues and can discuss them with a level of understanding. It is not expected that you have undertaken a

complete literature search but it is expected that you have made a start and read around the subject. You cannot

develop your research questions or hypotheses unless you have done this. It should be 600-800 words long and end

with a list of full references. A literature review is not done book by book (or source by source) but is integrated and

written up under key themes and issues that may or may not have headings.

In your dissertation, the literature review is much more substantial but the same principles apply. You should use an

integrated style presented under clear and logical headings. Most of what follows is relevant to both the proposal and

to the dissertation - it is really a matter of scale that differentiates them.

A literature review is a written summary of the findings from the literature search. Its purpose is to provide proof of

scholarship - to show that you know the literature and you have the intellectual capacity to read it, develop the

theoretical argument and be able to give a critical, constructive analysis of that literature.

Writing a review is a demanding exercise. You will not get it right first or second time. Much material that you have

found and recorded will not be used. Editing and discarding information is heartbreaking but essential.

Some tips on writing up the literature

Start writing as soon as possible.

Select and cite only relevant material - you do not need to include a mention of everything you read.

Group the material into categories and comment upon the most important features.

Be critical. An uncritical review tends to be descriptive, where everything merits a one paragraph entry, such

as 'Smith (1985) found...; Jones (1987) found....' A critical review shows that you have studied existing work

in the field with insight by pointing out the strengths and weaknesses; by comparing the results of different

studies; and by evaluating theories, etc., with reference to your own study.

Use quotations to illustrate a point and add an extra dimension to your argument.

STRUCTURING A LITERATURE REVIEW

It is often difficult to decide how to organise the huge amount of information you have collected. The structure of each

dissertation will be different but there are some general principles and these are really the guidelines you should use

for any piece of academic writing. The dissertation is just much longer than most essays or other pieces of work.

Introduction to the literature review

There should be an introduction to your literature that signposts the content by stating the approach you will

take and puts forward the central ideas and purpose of the literature review. It 'sets the scene' and provides

a 'map' of where the literature review is going to take the reader and why. It should also stimulate interest. It

is likely that this part will have to be written after the main sections. It is not likely to be more than half a page

long but needs to be carefully crafted.

Main part

This should consist of discrete sections arranged in a logical order. Unlike an essay where paragraphs are

simply arranged in order without headings, a dissertation needs clear headings due to the size of the work.

Headings help the reader, and you, the writer, to keep on track. Each section should be devoted to one topic

or theme, and each paragraph within each section should confine itself to a single idea. The first sentence of

a paragraph should indicate what the paragraph is about in some way and then move on to develop that

idea supported by evidence and examples. Avoid having a lot of short paragraphs of one or two sentences.

Also avoid lots of lists. This may be appropriate for report and business-style writing but is not suitable for

essays or dissertations.

The key concept here is of developing an argument, and your tutors will be looking for the following:

o The writing shows a sense of purpose and direction, as though the writer knows where he or she is

going and is leading the reader there step-by-step.

o There is a definite central idea with reasons for it and evidence to back it up and support it.

o The writing may present a 'case' for a certain viewpoint.

o The writing is logical with ideas or events linked together in a logical sequence.

o The ideas are put together in a way that is clear to the writer and to the reader.

Conclusions

At the end of your literature review you must summarise and draw conclusions about the key points in your

writing. There needs to be a sense of completion to the whole piece; you need to 'round off' rather than just

stop abruptly. At this stage, you will discover just how much of your writing is descriptive and how much is

critical. It is only when you are writing using analysis and evaluation that you are likely to be able to draw

conclusions!

STYLES OF WRITING

There are many different ways of looking at academic writing styles and one way is to try and identify which of the

following styles you are using. All styles have their place but you need to be wary of spending too much time in your

dissertation on the first two.

Chronological writing

This style of writing looks at events over a period of time and relates them chronologically or in date order. Thus,

historical texts would follow this style. Often students want to give the historical background to their research area

and this is often appropriate. However, be careful not to overdo this. If your research question relates to the 'here and

now' (and most do), then it is not appropriate or relevant to have three-quarters of your literature review giving the

historical background. It may be appropriate for you to read it so that you understand the context of your study, but it

is usually appropriate to confine yourself to a brief summary of the key points, or use this material in the introductory

chapter to the dissertation.

An example of this would be a student who wanted to research into whether the media treats women and men

athletes the same in terms of sports reporting. There is a vast amount of literature on the historical inequalities in

sport which make fascinating reading and could perhaps be mentioned. However, this student would be much better

advised to concentrate the bulk of their literature on athletics, sports coverage in the media, gender bias in media,

and content analysis of gender bias.

Descriptive writing

It is likely that your literature review will contain descriptive writing which is appropriate for outlining characteristics,

models, theories and diagrams, etc. However, beware of this style! If all your writing is descriptive then you will not

show that you have the ability to critically review the literature and, therefore, you need to include some of the

following styles.

Cause and effect writing

Here you identify the link between one activity and another or one variable and another. What happened? Why did

something happen? What were the consequences? This may be an appropriate style of writing in your literature

review and is also useful for writing up your findings.

Compare and contrast writing (theme-by-theme)

Here you take two or more concepts or ideas and compare them (looking for similarities) and contrast them (looking

for differences). This often occurs in an essay where you may be specifically asked to do this. In a literature review,

you may have identified a number of models or theories and want to compare and contrast them in order to develop a

rationale for which one to use as the basis for your dissertation, or to help you construct a model on the best or most

appropriate aspects of each.

Summarising writing

Sometimes you are asked to summarise something for a piece of work, but this style is particularly appropriate for

making notes on key topics, summarising the key points. When doing this, think about why you wish to include this

idea and how it fits in with your overall dissertation. You may need to summarise the key points of someone else's

work in your dissertation. Summaries are often descriptive.

Analytical writing

Analysis means breaking things down into their constituent parts. For example, if you were to analyse milk you would

find, in simple terms, that it consisted of a large amount of water, protein, sugar and various minerals and vitamins. In

academic writing this means you have to 'unpick' or 'tease out' a concept in order to answer questions such as:

Evaluative writing

In order to evaluate, you have to make a judgement or put a 'value' on something. Is it 'good' or 'appropriate for the

purpose', or 'inadequate' or 'lacking evidence', or 'useful' and so on? To do this, almost certainly you will first have

analysed the data in order to make your judgement. Analysis and evaluation go hand-in-hand. You then have to go

one step further and say why something is 'useful', or whatever, and give reasons for your judgement.

It is quite likely that your dissertation will contain most, if not all, of the above styles of writing. They apply not only to

writing up the literature but to all sections of your work. There is also some overlap between them. For example,

chronological writing could also encompass any of the other styles although it is often used descriptively - first this

happened, then that happened. Your tutors will be looking for you to use a range of writing skills in your dissertation

as appropriate, but make sure that you minimise the descriptive writing and try to develop the other styles.

Language and writing

Note some key points about language:

Keep it simple and clear.

Do not use a long word when a short one will do.

Try to have an average sentence length of 15-20 words; long sentences are hard to follow.

Always use the 'third person'. Do not use words such as 'I', 'me', 'my'. For example, write, 'It could be

considered that', and not, 'I think that'.

Check spelling and grammar; if this is a weak area then improve by asking for feedback from your tutor;

reading texts on grammar, punctuation and spelling, etc.

Try to write in a way that will be interesting to read. Your tutors have a lot of dissertations to mark and one

that is interesting and enjoyable to read will be memorable.

You need to show that in addition to describing something you can interpret, apply, evaluate and reach

conclusions. Some useful words and phrases are given below to help you identify when you are doing what!

Writing is a skill like any other - it takes practice. It is likely that your skills in this area, after studying for two or three

years, will already be quite good. However, if you are returning to study or are much more used to writing in a report

format, then you may find it necessary to do quite a lot of work on your writing skills. This will be useful for all

modules, not just the dissertation.

One of the common features of a good essay or other piece of academic work is the appropriate use of references

and quotations. In both cases, they will add scholarly weight to your work, but they must be properly dealt with.

Any idea which is not your own but comes from someone else must be acknowledged in your writing. This

acknowledgement of the source of the information is called a reference or citation.

Referencing aims to:

help the reader to distinguish between your ideas and those from other sources

give authority to ideas that you are putting forward by showing that they have independent theoretical

support

enable readers to check and follow up for themselves the authors you have read

indicate in a concise fashion the existence of the body of published work that you have used in preparing

your essay, report, etc.

avoid the accusations of plagiarism.

You will lose marks if you do not reference correctly.

Using references within your text

There are many ways to give a reference used within the text. Perhaps the most popular method, because it is the

simplest, is the Harvard System - where the author's surname is followed by the year of publication. This is also

known as the 'author-date' system and is the method we advise you to use in all your writings whilst studying on this

programme.

As well as the general aims of references given above, references within the text are specifically used to:

provide support for ideas (see 'a' below)

cite supporters of ideas (see 'b' below)

acknowledge the source of ideas (see 'c' below)

establish facts (see 'd' below).

The standard ways of giving a reference within the text using the Harvard system, and the various possibilities that

can occur, are illustrated in the following examples:

If there is one author who is the subject of the sentence (such as 'a' and 'b' above) the date of publication is put in

brackets (parenthesises) after the surname.

If the reference to both the author and the date of publication are not a main part of the sentence (as in 'c' and 'd'

above) add them parenthetically at the end of the sentence.

If you refer to Smith again within the same paragraph, there is no need to quote the year. You can say, for example:

As Smith argues...

or

Smith's position on this is...

Here the reference to Smith indicates that you are still presenting the ideas of his 1997 article. If, in another

paragraph, you wish to refer to Smith again, revert to specifying the name and the date - Smith (1997)

Where there are two or more co-authors, all names are given when first cited.

For more than one author, place the authors in chronological order.

If the work is the product of an organisation and does not carry an individual author's name, the name of the

organisation is used:

Organisation:

In a survey of households in the UK in 1997, it was found that 80% of them had a washing machine (NOS 1999).

If you have read an article by Elliott written in 1996 in a book by Kitson and Campbell that was written in 1998, cite

the author who wrote the article (Elliott) not the author of the book in which you found the material (Kitson and

Campbell).

Quotations:

You want to quote only when it is especially important for your reader to see and appreciate the precise wording of

the original. You may choose to do this to:

provide the reader with the original when you are discussing the text in detail

illustrate a point precisely

discuss interpretations of a well-known authority

respect the wording of the original when the impact would be lost if you tried to explain it or paraphrase it.

Quotations should be directly quoted, using the exact words, punctuation and spelling of the original author

irrespective of the source. A specific quotation from a text should always be identified with its page number after the

date of publication. A colon separates the year and the page number. All quotations should be enclosed within

speech marks. It is common to italicise the quotation as well.

...can be included in the main text.

Longer quotations should be started on a new line and indented further from the left-hand margin than the main text.

It is not appropriate to put long passages in quotation marks. For an extended citation, you should summarise the

material in your own words and give the appropriate reference. As a very rough guide, you would not expect to use

more than one or two sentences in quotes on each page of your text.

Bibliography

A bibliography is a list of all references, whether cited or not in your work, which have been consulted in the

preparation of the work. It should be possible to see from the bibliography, which texts are books and which are

articles. Unfortunately, there are many variations in bibliographic styles.

The variations are based on the use of upper and lower case letters, commas and full stops, italics, bolding and

underlining, and the position of the various elements that make up the reference.

Do not devise your own system. For simplicity and consistency, the following approach to constructing and writing

a bibliography should be adhered to and is based on the Harvard System. The bibliography should:

be in alphabetical order of authors' surnames. If there is no author, the issuing organisation should be used

appear at the end of the work and not at the end of each chapter or section

be a single listing and not be sub-divided into cited references and non-cited references, or books and

journals, etc.

For a book, the order of the reference is:

author's surname, followed by the initials

year of publication in round brackets

title of the book, italicised and only the first word and proper nouns capitalised

edition number, if appropriate

place of publication followed by a colon

name of the publisher.

For an article in a journal the order is:

author's surname, followed by the initials

year of publication in round brackets

title of the article in speech marks

title of the journal in italics.

Then, if you also know:

month or date of issue, the volume number, the issue number

page number - preceded by 'p.' for a single page and 'pp.' for multiple pages.

For organisations the order is:

name of organisation

year of publication in round brackets

title of the article in speech marks.

For articles in non-academic sources:

For articles in non-academic sources, such as a newspaper or manuals, the structure and order is dependent on the

availability of detail, such as the author's name, and is a mix of the above procedures.

For a cited author quoted in another text:

cited author's surname followed by the initials

year of the cited author's publication in round brackets

title of the cited author's book (italicised) or article (speech marks)

author, year, title, location and publisher of the source text preceded by the words cited in, all enclosed in

square brackets.

For an Internet source:

The reference style for Internet sources uses a modified Harvard system:

author's surname, first name or homepage/institution/university/business name

date if available

<email address if given>

title of document

Internet address URL www.address

date site visited.

Remember that you should be able to:

cite an author (and variations) using the Harvard System

quote an author

construct a bibliography using the Harvard System

be able to differentiate between books, articles, organisations and Internet sources when listed in a

bibliography.

SUMMARY

In this unit, you have worked through the skills of searching and reviewing the literature, making notes and keeping

bibliographical records. You have also worked through some theory on writing more effectively, developing your

writing structure and style. These skills need practising and are applicable to any other modules you are studying.

Practise them and get feedback from your tutors. You should also show a sample of your draft literature review to

your supervisor who will be able to help you with these skills.

By now you will have a clear research question and will have read a lot of literature on your topic. Only when you

have completed these two essential first stages are you ready to think about planning your overall approach to

collecting data. Data is effectively another word for information that can be found through secondary or primary data

collection. It is important that you understand all the various ways of collecting data so that you can decide which to

use for your own research. It is worth remembering at this stage that all methods of data collection can supply

quantitative data (numbers and statistics) or qualitative data (usually words or text).

All methods of data collection can supply quantitative data (numbers, statistics or financial) or qualitative data (usually

words or text). Quantitative data may often be presented in tabular or graphical form. Secondary data is data that has

already been collected by someone else for a different purpose to yours. For example, this could mean using:

data collected by a hotel on its customers through its guest history system

data supplied by a marketing organisation

annual company reports

government statistics.

Secondary data can be used in different ways:

You can simply report the data in its original format. If so, then it is most likely that the place for this data will

be in your main introduction or literature review as support or evidence for your argument.

You can do something with the data. If you use it (analyse it or re-interpret it) for a different purpose to the

original then the most likely place would be in the ‘Analysis of findings’ section of your dissertation. A good

example of this usage was the work on suicide carried out by Durkheim. He took the official suicide statistics

of different countries (recorded by coroners or their equivalent) and analysed them to see if he could identify

variables that would mean that some people are more likely to commit suicide than others. He found, for

example, that Catholics were less likely to commit suicide than Protestants. In this way, he took data that

had been collected for quite a different purpose and used it in his own study – but he had to do a lot of

comparisons and statistical correlations himself in order to analyse the data. (See Haralambos, 1995, for

details of Durkheim’s work).

Most research requires the collection of primary data (data that you collect at first hand), and this is what students

concentrate on. Unfortunately, many dissertations do not include secondary data in their findings section although it is

perfectly acceptable to do so, providing you have analysed it. It is always a good idea to use data collected by

someone else if it exists – it may be on a much larger scale than you could hope to collect and could contribute to

your findings considerably.

As secondary data has been collected for a different purpose to yours, you should treat it with care. The basic

questions you should ask are:

Where has the data come from?

Does it cover the correct geographical location?

Is it current (not too out of date)?

If you are going to combine with other data are the data the same (for example, units, time, etc.)?

If you are going to compare with other data are you comparing like with like?

Thus you should make a detailed examination of the following:

Title (for example, the time period that the data refers to and the geographical coverage).

Units of the data.

Source (some secondary data is already secondary data).

Column and row headings, if presented in tabular form.

Definitions and abbreviations, for example, what does SIC stand for? For example, how is ‘small’ defined in

the phrase ‘small hotel’? Is ‘small’ based on the number of rooms, value of sales, number of employees,

profit, turnover, square metres of space, etc., and do different sources use the word ‘small’ in different

ways? Even if the same unit of measurement is used, there still could be problems. For example, in Norway,

firms with 200-499 employees are defined as ‘medium’, whereas in the USA firms with less than 500

employees are defined as ‘small’.

There are many sources of data and most people tend to underestimate the number of sources and the amount of

data within each of these sources.

Sources can be classified as:

paper-based sources – books, journals, periodicals, abstracts, indexes, directories, research reports,

conference papers, market reports, annual reports, internal records of organisations, newspapers and

magazines

electronic sources– CD-ROMs, on-line databases, Internet, videos and broadcasts.

The main sources of qualitative and quantitative secondary data include the follwing:

Official or government sources.

Unofficial or general business sources.

The output of all publishers of non-official sources is included in the most comprehensive directory available:

Mort D. (1997) Sources of Unofficial UK Statistics 3rd Edition Aldershot: Gower

The guide lists 1,059 statistical titles and series published by 635 different organisations. It excludes one-off surveys

or market reports.

The arrangement is alphabetical by organisation with details of titles produced and contacts for further information. It

lists references to the following types of sources:

trade associations

trade and other journals

private research publishers

stockbroking firms

large company market reports

local authorities

professional bodies

academic institutions.

European Union (Community) sources.

International sources.

o Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

o United Nations and related organisations.

Sources for the last two categories are many and varied. If your dissertation requires these sources you need to

conduct a more thorough search of your library and perhaps seek the assistance of the librarian.

In primary data collection, you collect the data yourself using methods such as interviews and questionnaires. The

key point here is that the data you collect is unique to you and your research and, until you publish, no one else has

access to it.

There are many methods of collecting primary data and the main methods include:

questionnaires

interviews

focus group interviews

observation

case-studies

diaries

critical incidents

portfolios.

Click on one of the above icons for the information in LRN format.

The primary data, which is generated by the above methods, may be qualitative in nature (usually in the form of

words) or quantitative (usually in the form of numbers or where you can make counts of words used). We briefly

outline these methods but you should also read around the various methods. A list of suggested research

methodology texts is given in your Module Study Guide but many texts on social or educational research may also be

useful and you can find them in your library.