Responsiveness and Social Expression; Seeking...

Transcript of Responsiveness and Social Expression; Seeking...

12 ACADIA05: Smart Architecture

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

Responsiveness and Social Expression; SeekingHuman Embodiment in Intelligent Façades

Sachin Anshuman1

1 Glasgow Caledonian University

Abstract

This paper is based on a comparative analysis of some twenty-six intelligent building facades and sixteenlarge media-facades from a socio-psychological perspective. It is not difficult to observe how deployment ofcomputational technologies have engendered new possibilities for architectural production to which surface-centeredness lies at that heart of spatial production during design, fabrication and envelope automationprocesses. While surfaces play a critical role in contemporary social production (information display,communication and interaction), it is important to understand how the relationships between augmented buildingsurfaces and its subjects unfold. We target double-skin automated facades as a distinct field within building-services and automation industry, and discuss how the developments within this area are over-occupied withseamless climate control and energy efficiency themes, resulting into socially inert mechanical membranes.Our thesis is that at the core of the development of automated façade lies the industrial automation attitudethat renders the eventual product socially less engaging and machinic. We illustrate examples of interactivemedia-façades to demonstrate how architects and interaction designers have used similar technology to turnbuilding surfaces into socially engaging architectural elements. We seek opportunities to extend performativeaspects of otherwise function driven double-skin façades for public expression, informal social engagementand context embodiment. Towards the end of the paper, we propose a conceptual model as a possible methodto address the emergent issues.Through this paper we intend to bring forth emergent concerns to designing building membrane wheretechnology and performance are addressed through a broader cultural position, establishing a continual dialoguebetween the surface, function and its larger human context.

ACADIA05: Smart Architecture 13

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

Introduction

Since sometime, relationships between the humansubject and the built environment have beencentral in architectural discourse again. Afterdecades of the machine’s influence through theindustrial revolution until wake of the digital era,we have come to focus again on the importanceof humane space, urban responsibilities of builtstructures and its relationships to the end user.While it is no news that built environments havelasting effects on human psychology, shaping ofcollective identities and social behaviour[Norberg-Schulz 1971], [Rapoport 1969], thesubject is re-visited recently through studies inspatial psychology [Vidler 2000], environmentalcognition and architectural theories in accordancewith emergent digital revolution [Zellner 1999],[Oosterhuis 2002], [McCullough 2004]. Buildingsurfaces or façades form an important area ofinvestigation for how they represent an initialinterface to our interaction with built entities andurban environments in general. Notion of responseand media augmented expression are increasinglyaddressed in contemporary architectural designthrough incorporating new digital techniques inan attempt to equip architectural surfaces with newforms of expression [Rahim 2002], [Krueger1996]. Studies in consumer product psychologyrepetitively suggest that the value of products areoften determined against the expression theyrelease for how they signify abstract persona andallow us to project ourselves through theirownership [Reeves 1996][Norman 1993].Symbolic exchange-value of the commoditypositions the possessor within a class where theconsensual meaning associated with the objectsfinds manifestation. What the object signifies (itssign value) often is more important in social termsthan what the object does (its utility value), andtherefore, it is not only the product that weconsume, but the idea of the product, and whatthe product will allow us to become. Places aredefined similarly - less by location, buildingattributes, technical efficiency or landscape, andcommunities; but by the focusing of collectiveexperiences and subjective embodiment intoparticular spatial conditions [Dourish 2001].Architecture is a notion of space inextricablylinked with, and defined by, the wealth of humanexperience and use occurring within it. Investedby subjective values, philosophical projections,and cultural influences, architectural space isdefined far beyond the physical envelope.

Augmenting such space would requireunderstandings of embodied existence, socio-psychological aspects of space and its operativeprinciples.

Intelligent Building

Concepts of intelligent building and smart space,however, address technologies for built spaceswith a distinct approach that is often utilitarian.Energy efficiency continues to be a top priority inwhat constitutes an intelligent building [Szell2003], [Sharples 1999]. Early approachesessentially focused on two basic objectives -human comfort through climate control, and cost-effective energy management. Although thereexists no fixed opinion or definition of the term“Intelligent Building”, it is important to note howeven the earliest definitions address the notion ofresponsiveness through electronic system controls,time based programmability of building servicesand integrated operation [Wigginton 2002]. Unlikethe use of digital technologies in architecturaldesign, which focuses on augmenting humanexperience through creative technological means,monotony of energy efficiency theme remainscentral in design and production of intelligentbuilding façades. This is apparent in IntelligentBuilding definitions, which define the IntelligentBuilding as the one that maximises efficiencywhile allowing effective management withminimum costs [IBC, Intelligent BuildingInternational], [Kim 1993], anticipates conditionsand active forces [Kroner 1997], optimizesstructure, systems, services and management tohelp business owners, property managers andoccupants to realise their goals in cost, comfort,convenience, safety, long term flexibility andmarketability [Kim 1996], or be able to respondto organisational change and adapt to new tasks[Harrison 1994]. Basic objectives of IB systemscan be divided in four categories, namelyIncreased environmental comfort, Energyoptimisation, Security, and Automated buildingmaintenance procedures. Façade engineeringplays a major role in implementing theseobjectives. However for architecture, in its longhistory, façade was a social frame first and becameoperable equipment (automated envelope) onlylater [McCullough 2004]; unlike developments incomputing – an operation based system first;whose developmental trajectory is lately beingquestioned altogether for being an orthodoxextension of industrial automation slogan that

14 ACADIA05: Smart Architecture

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

focused around process automation and not thehuman subject. With recent explosion ofubiquitous computing and the shifting focus ofinterface design to what is now termed interactiondesign denote popular reaction to a generalrealisation to move away from idiot-proof, button-based interfaces that perpetuate such industriallegacy and rethink the idea of interaction from adeeper perceptual and social level. Recent interestof HCI in Heidegger’s phenomenology and itsapplication to the design of computational systemarchitecture denote such shift [Dourish2001],[Coyne 1999]. Façades designed andmanufactured with industrial automation outlooksignificantly lack sociability, expression and thusengagement alike, for how the human relationshipswith the building, its elements and the socialsurrounding of the building are considered lessimportant from the start. This reflects not only inthe assigned functions and aesthetic qualities offaçade, but also in the interfaces developed tocontrol them, which form primary means ofoperation and exercising offered affordance.Systems that eventually develop around theenergy/cost/climate parameters hence remainlimited in terms of how human subject identifieswith them.

How Intelligent Facades are Socially Inert?

In recent years, interaction designers and architectshave demonstrated potential in physical computingand embedded systems in large interactivesurfaces. As the need to connect architecture andinteraction design comes from overlapping subject

matters and escalating social consequences, thepath towards such connection involves a shift fromforeground objects to background experiences.[McCullough 2004] It is in this underlying attitudethat these projects differ significantly fromconventional function driven intelligent façades.

Most automated façade systems invite little bodilyparticipation both from the occupants’ perspectivewithin the building and larger urban participationfrom the outside. Sense of belonging in spatialsettings involves a perception of insideness andnot the empirical attributes of physical construct.Foundations of embodiment are rooted in suchperception, which is largely governed by trust,support networks, collective experiences, interests,types of transactions, history, landmark, proximityetc. [McCullough 2004] Allocation of interactionsystems acknowledging such interventions lacksignificantly in the design of automated facades.For example, bay wise louver control for optimallighting in the systems we studied usually involvedthe user participation in two forms. One, throughprovision of a push-button based system-overridepanel and two, in some cases, through pyro-electricinfrared occupancy sensors mounted at room-levelresolution to interpolate the control of artificiallighting. The former denies physical contact andhence reduces the spectrum of control throughlimited push buttons to control a few aspects ofwhat are otherwise elaborate architecturalelements, and the latter comes through as overtlyimpersonal and dissociative for its popularpsychological association with voyeur and silent-surveillance. Such automated provisions do not

Figure 1. BIX communicative display skin embodies 930 fluorescent lamps integrated in acrylic glass façade of the biomorphicstructure

ACADIA05: Smart Architecture 15

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

efficiently replace the complex ritual of interactingwith a window, for example, for view and/or lightand/or breeze but rather reduce the scope of thearchitectural elements to singular functions –which in this case is, seamless maintenance ofinternal illumination level.

While many intelligent facades are now equippedwith sophisticated Artificial Neural Network(ANN) based control systems, to learn occupantactivity patterns and climatic variations, perceivedsense of response (and so façade as an activeentity) remain low to the occupants. Most louvercontrol systems, for example, set re-adjustmenttimings to 30mins or more to avoid continuousmovement and thereby reducing disturbance.Studies in social psychology [Brown 1979],[Kolers 1972] show that lack of visible motionresults in perceived inertness for how cognitionfails to assess activeness of an entity [Sternberg1986, 1981], [Livingstone 1988], [Bolivar 1995].Therefore even though actual intelligence/responsivity is significant, perceived intelligence/response remain low. We will later see how ininteractive media-façades, this quality issignificant and there fore results in increased socialparticipation. Collective motion of façadeelements, closely tied up with environmentalsensors and weather stations, does not respond tothe user except for local override through wallmount control panels.

It is well known that industrial standardisationprocesses exert unity at a mass level by extractingindividual identities [Jencks 1998]. One of thewell-criticised downsides of modernistarchitecture has been standardisation. Thiscontinues to reflect, for obvious reasons, incontemporary construction practices too.Personalisation of space in traditional spatialsettings came through authorship, display andcontrol of personal objects, attributes, and theirorganisation in space. (What makes something myplace?) In modern settings these practices arereduced to personal notes, pictures, greeting cardsetc stuck on interior partition surfaces, PC-wallpapers, demographies of personal objects onwork desks and other surfaces etc. Standardisationof surface-elements both within façades, and inother interior surfaces, with their authorshipsassigned to automated systems, reduces thepotential of personal projection, authorship andinteraction with these elements. Moreover, to

Benedikt, we orient spatially not only through eyesbut also with tactile body [Benedikt 1992];repetitive standardised curtain-wall elementsconfiscate unique identification of places andlocations along the surface and render thespectator-body, in turn, as the object of operationrather than subject of action [Bloomer 1977].Perception of locations and places are rooted inspatial relationship networks, which are at theheart of our conceptual system [Lakoff 1980].

In case of operable components encased betweentwo transparent sheet-glass layers of double-skinfaçades, or automated doors, air-inlets, shadingelements etc, invoke tactile detachment. Suchdetachment from tactile contact, and thereforefrom direct control, eliminates a variety ofactivities related to traditional building elementsemerging from physical contact [leaning on asurface, peeping through a hole, sitting onwindow-sill, opening/closing doors/windows etc].Lack of social engagement, personal projectionand tactile contact, seemingly forbids personalaffiliation with these systems. Such humaneinteraction with conventional building-elementsforms the bases for embodiment in traditional builtenvironments, which remain low in mechanizedintelligence driven building surfaces.

While it may seem that machinic appearance ofautomated surfaces may account for alienation too,there is evidence in psychological literature thatthis condition does not quite prevent us fromidentifying with technological objects. Popularexamples of such theory come from researchshowing how we assign personalities totechnological objects such as televisions, mobilephones and other new media objects [Reeves1996]. It is not in the way automated façades lookbut what they signify (through the level of ourengagement with them) is important in socialterms. It is at this level that the design of operablefaçades lack affordance.

While primary agendas of Intelligent buildingmembranes remain rooted in climatic adaptation,security and cost-effective energy optimization,we notice very little significance of these self-contained surfaces socially in urban settings. Thisunresponsiveness is especially noticeable whencompared to highly expressive surfaces ofinteractive media-facades.

16 ACADIA05: Smart Architecture

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

Response and Interaction in Media Façades

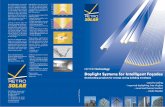

BIX façade at Kunsthaus Graz, for example, dealswith the issue of communication and embodimentthrough the deployment of low-resolution displaytechnologies enabling the building surface todisplay video-like images through controllingbrightness of the individual fluorescent tubes. Theissue of embodiment is addressed through devisingan additional web based service allowing artiststo compose and post video impressions to thesurface, online; expanding this way, theinteractivity of the Kunsthaus beyond geographicproximities. At a local level, the institution projectsitself through soft yet dynamic expression releasedby the built form. In terms of image resolution,the BIX façade (930 pixels) is smaller than thescreen of a common mobile phone. Such lowresolution stretched across complex doubly curvedstructure pushes the image content to being highlysuggestive and abstract. Although most mediafaçades involve such low to medium imageresolution, success of these schemes lies in the inthe way foveal and peripheral vision works incognitive processes. Studies in image size,resolution and motion [Reeves 1993], [Nystrom1992], [Detenber 1999] in television-screens andcinema suggest that level of arousal and therebyinvolvement is directly proportional to image sizebut does not depend on resolution [Hochberg1986]. Images that extend to peripheral boundaryare more involving. Also, eyes are more sensitiveto motion in peripheral vision than the definitiveattributes of the image [Nystrom 1992], [Hatada1986]. Façades such as the BIX communicative

display skin draw on these specificities ofperception and invite engagement, despite lowresolution. Less definitive abstract movementsresembling to those of real-world objects andpeople thus characterize these surfaces and inviteengagement.

Approaches to interaction in media façades varysignificantly. Hyposurface (Fig 2) responds toambient sounds and user position/motion byundergoing topological transformations. Kineticwall (Fig 3) similarly engages passer by on thestreet by collective motion of Whisks like roboticfaçade members reacting in real time to humanmovement. Instant physical response, howeverabstract, induces a sense of live presence andattention, making the façade an active part of urbanlife. Although majority of these installations serveno utilitarian function except for inviting activeparticipation, their appropriateness in socialcontext is significant. Moreover, although the levelof computational intelligence or logic-complexityof such systems is low [Anshuman 2003];perceived intelligence and responsiveness remainssignificantly high.

It is only recently that surface has gained a newfocus in design as a ground for display,communication and interaction that now requiresre-appropriation of otherwise distinct technologiesthat form integral part of the surface formation. Amore integrative outlook to surface design andintegration of digital or electronic technologies atmaterial level is now beginning to be demonstratedin façade systems. While conventional intelligent

Figure 2. Hyposurface is pneumatically driven animate membrane developed by dECOi

ACADIA05: Smart Architecture 17

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

façades demonstrate low embodiment fromoccupants’ perspective, media façades lack realfunction. There are clear analogies to be drawnfrom media-façades that could inform the designconventions of intelligent façades.

Discussion

Service Segregation and Architectural Surface

We think that the reasons for the automated façadeengineering to have developed solely aroundenergy efficiency and climate control parametersare rooted in the historical kinship of this field tobuilding services and not architectural design.Modernist agendas of seeking efficiency throughservice segregation and efficient function deliverynegate the higher-level design issues concerningembodiment, expression or situatedness in socialcontexts. This holds true from the times whenelectrical or other technologies were beginning tobe integrated in architectural production. Withinthe first decade of the twentieth century, methodsfor delivering electrical distribution withinbuildings were developed at an industrial scale.With increasing demand, electricity soon becameintegrated into spatial production without formalintrusion as a part of architectural design. Cavitywalls later emerged as a new component type thatradically restructured the conventional materialityof architectural surface, and quickly became thesite for integrating unified building serviceinfrastructures such as plumbing, heating, cooling

and electricity, while remaining distinctlyunrelated to neither spatial configuration norsurface design. The notion that the distributionservices should be architecturally unrelated,usually reflects modernist agendas of industrialoptimization through segregation, and modularity,as much as the often-stated practical assertions ofconvenience and ease of construction [Kennedy2004]. Persistence of this logic has produced a setof ideas and conventions that continue to influencecontemporary practice that include façadeengineering as part of intelligent buildingapproaches. This segregation resulted intoconceptual and physical segregation of serviceprovision infrastructures and their materialmediums (i.e. lighting fixtures, wall mountswitches, HAVC infrastructure being distinct fromspatial design). With the proliferation ofinformation technologies, these systems werefurther divided into four operating areas namely,Energy efficiency, Life-safety systems,telecommunications systems, and workplaceautomation [the National Academy of Sciences’committee for “electronically-enhanced”buildings], which over time merged into twobroader areas: Facilities Management (FM)(energy and security systems) and InformationSystems (ITC)(telecommunications andworkplace automation systems), forming twoprimary cores of contemporary building services’architecture [Szell 2003] (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Kinetic wall is prototype surface developed by Kinetic Design Group at MIT

18 ACADIA05: Smart Architecture

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

This division is especially evident in the intelligentfaçade examples from the last decade. In general,FM deals with the physical structure itself and howit is operated. It finds manifestation through façadeelements and floor-concealed HAVC, security andfire systems. Various IB standards (appendix) havesince emerged to automate FM (Fig 7). ITC onthe other hand, refers to the way information ishandled within the building - it operatesindependently from façade, structure or intrinsicbuilding elements. ITC systems dealing with web,email, LAN, WAN networks, workstations, IOperipherals, telephone systems, and in some casespersonal ubiquitous devices, is manifested onlythrough object-level entities distributed withinbuilding envelopes.

An Alternative Model

What strikes one are the underlying organizingprinciples in the current IB systems model. WhileFM continues to decrease human interventionthrough typical strategies for programmed start/stop, duty cycling, set-point resets, sensor basedadaptive control and optimal energy routing forvital building functions, ITC continues to increase

interpersonal and building’s interaction withoccupants and appliances. With the spread ofcontext-aware computing [Weiser 91] newchannels of connecting human activities toinformation are now opening with various sensing,processing and networking technologies. Thesedevelopments have demonstrated potential forarchitectural spaces to perform in previouslyunimaginable manner, that is, through augmentedexperience, expression and interaction [Gage1998], [Krueger 1996]. Unfortunately, materialmanifestation of current ITC systems in IB systems(desktop PCs, telephones, printers, video-conferencing facilities etc.) form a detached inner-layer consisting of distinct objects and serviceswhich are not commonly perceived as parts ofbuilding anatomy. FM, through automation,continues to detach definitive formal elements ofbuilt entities from its occupants; to which, façadeand other surfaces are operative grounds. For itis these material surfaces, that form essentialmediums for occupant’s social embodimentthrough interaction. Optimizing built surfaces forexpression, display and interaction holds thepotential to produce a heightened presencecharacterized by the intensity of experiential

Figure 4. Primary model of contemporary building services’ architecture

Figure 5. Diagram showing the current model of IB with unrelated FM and ITC (Left), and the proposed model (Right) forincreased user embodiment

ACADIA05: Smart Architecture 19

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

responsiveness beyond mechanical automation,and therefore embodiedness within builtstructures. The alternative model (Figure 5) takesintegrated approach to environmental handlingtogether with occupant information thought ITCsystem instead of FM and ITC performingindependently. ITC could therefore be optimizedfor it’s newly found potential to integrate objects,occupants and environmental inputs, and organizeheterogeneous output at a wider material level.This approach most importantly allows for inputfrom human actions (explicit keyed instructionsand implicit sensor data) and occupant attributesthat otherwise remain limited to interconnectedITC components. As ubiquitous computing markthe third wave in computing, interaction betweencomputational objects and mediated interpersonalinformation exchange will become more humancentred and context aware. Routing buildingmanagement procedures via ITC systems this wayallows for the response actions to be linked toarchitectural surfaces and built objects; makingthem expressive or responsive to their humancontexts. The increasing number of materialsthrough with digital technology can be distributedand information could be displayed(Electroluminescent materials, FoLED, SMA andpiezoelectric materials) expands the array ofintegrating such materials into spatial production;extending this way, responsive qualities both viarobotic and audio-visual means.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have tried to demonstrate twodistinct approaches to façade design. Keepingautomated double skin façade in focus, we haveillustrated variety of media installations developedby architects, interaction designers and mediaartists. In such comparative perspective, it is nothard to notice that public expression andinteractivity of large media façades result inheightened social participation and informalengagement that differ significantly from video-screen and large LED displays conventionally usedin urban settings. Real time responsiveness ofthese systems to their user and/or larger socialcontexts, provide these buildings with an addedsocial dimension that usually lacks in automatedfaçades. We have proposed that the reasons forsuch inertness are rooted in the manner in whichsuch systems are conceptualised and thefoundations that they are based on. Control andengagement afforded to the end user, both

functionally and socially, require an outlooktowards design that in fact increases the affordanceoffered by such automated elements, rather thanreducing its participative spectrum. We havedemonstrated this limitation by comparing thebutton based louver control with the manualcontrol of conventional window and the ease ofoperation and variety of engagement afforded bysuch element. We propose for widening suchengagement spectrum through better interactiondesign where technology does not reduce humandimension otherwise inherent in an entity.Although it was out of the scope of this paper todiscuss technologies driving such systems, it wasobserved during the study that both media-façadesand double skin membranes use very similartechnologies to achieve their respective goals.While expression, experience and userparticipation form primary agendas for mediafaçades, energy efficiency and seamless controlcontinue to predominate developments inautomated double skin membranes. Lack ofexpression and interaction preclude these rathermachinic systems from being sociable andengaging. We have also argued that the reasonsfor the lack of such objectives in their design arerooted in the relatedness of this field to the buildingservices that throughout history operated alongsidearchitectural design but were never an activecomponent of architecture. While the growth ofubiquitous computing now raises new issues toinfuse computational properties and media ineveryday objects and surfaces, this continuumpushes the building industry to re-organize andadapt to new integrated processes of materialdesign and their spatial manifestation. Architecturemust then operate to site these properties withinthe discipline and argue for the value of theirprojective effects that could create new conceptsfor energy distribution, spatial experiences, andexpression; giving the discipline a more centralrole among other contemporary modes of culturalproduction. Current form of ITC systems holdsthis potential, and must therefore be optimized toact as a central core connecting futureinfrastructural, spatial and human components. Forit is in doing so, that the architect would be ableto engage processes of technical and imaginativeengineering required for adapting and projectingspatial concepts for the material character of atechnology that has remained historically outsideof architecture, but is now central to our culture.

20 ACADIA05: Smart Architecture

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

Appendices

Table 1: User interaction and climatic input in intelligent façades

ACADIA05: Smart Architecture 21

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

Table 2: Existing Intelligent Building Standards and Attributes

22 ACADIA05: Smart Architecture

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

References

Anshuman, S., & Kumar, B. (2003). A Frameworkfor Designing the Responsive Skin. In Ciftcioglu,O., & Dado, E. (eds.) Intelligent Computing inEngineering. Delft Netherlands: Foundation forDesign Research SOON.

Benedikt, M. (1992). Cyberspace, First Steps.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bloomer, K.C. & Moore, C.W., (1977). BodyMemory and Architecture. London: YaleUniversity Press.

Bolivar, V.J., & Barresi, J. (1995). Giving Meaningto Movement; A Developmental Study. EcologicalPsychology, 7(2), 71-97.

Brown, E.L., & Defenbacher, K. (1979).Perception and the Senses. New York: OxfordUniversity Press.

Colomina, B. (1992). Sexuality and Space;Princeton Papers on Architecture. MA: PrincetonArchitectural Press.

Coyne, R. (1999). Technoromanticism, DigitalNarrative, Holism and the Romance of the Real.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Detenber, B., & Reeves, B. (1999). Motion andImage Size Effects on Viewer Responses toPictures; Application of a Bio-Information Theoryof Emotion. Journal of Communication(1), 23-34.

Dourish, P. (2001). Where the Action is.Cambridge MA: MIT Press124-125

Gage, S. (1998). Intelligent interactivearchitecture. Architectural Design 68(11-12), 80-85.

Harrison, A. (1994). Intelligence quotient; smarttips for smart buildings. DEGW, architecturetoday(46).

Hatada, T., Sakata, H., &Kusaka, H. (1980).Psychological Analysis of the Sensation of RealityInduced by a Visual Wide Field Display. SMPTEJournal, 89(8), 560-569.

Hochberg, J.E. (1986). Representation of Motionand Space in Video and Cinematic Displays. InK.R. Boff, L. Kaufman, & J.P. Thomas (Eds.),Handbook of perception and human performance(Chapter 22), New York, NY: Wiley

Jenks, C. (1995). Visual Culture. New York, NY:Routledge.

Kim, Jong Jin. (1996). Intelligent buildingtechnologies; a case of Japanese Buildings. Thejournal of architecture, Vol.1, No.2, 148-164.

Kim, Jong Jin. & Jones, J. (1993), A ConceptualFramework for Dynamic Control of Daylightingand Electric Lighting Systems. IEEE IndustryApplicantions Society, Ontario, 2-8.

Kolers, P.A. (1972). Aspects of Motion Perception.Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

Kroner, Walter M. (1997). An Intelligent andResponsive Architecture. Automation inConstruction(200).

Krueger, T. (1996). Like a second skin, livingmachines. Architectural Design(66), 9-10.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors WeLive By. IL: University of Chicago Press.

Livingstone, M., & Hubel, D. (1988). Segregationof Form, Colour, Movement, and Depth; Anatomy,physiology, and Movement, Science(240), 740-749.

Meyrowitz, J. (1985). No Sense of Place; TheImpact of Electronic Media on Social Behaviour.New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Norberg-Schulz, C. (1971). Existence, Space andArchitecture. New York, NY: Praeger.

Norman, D. (1993). Things that Make Us Smart,Defending Human Attributes in the Age of theMachine. Perseusbooks.

Nystrom, B.D. (1992). Perceived Image Qualityof 16:9 and 4:3 Aspect Ratio Video Displays.Journal of Electronic Imaging, 1(1), 99-103.

ACADIA05: Smart Architecture 23

S. Anshuman / Responsiveness and Social Expression

Oosterhuis, K. (2002). E-motive Architecture.Rotterdam: 010 publishers.

Rahim, A. (2000). Contemporary processes inArchitecture (AD) 70, No. 3, Wiley Academypublications.

Rahim, A. (2000). Contemporary Techniques inArchitecture (AD) 71, No.4, Wiley Academypublications.

Rapoport, A. (1969). House Form and Culture.Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

Reeve, B., Detenber, B., & Steuer, J.S. (1993).New Televisions; The Effects of Big Pictures andBig Sound on Viewer Responses to the Screen.paper presented to the information of systemsdivision of the international communicationassociation, Washington, DC

Reeves, B. & Nass, C., (1996). The MediaEquation, How People Treat Computers,Television, and Newmedia Like Real People andPlaces. Cambridge MA: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Sharples, S., Callaghan, V., & Clarke G. (1999). AMulti-Agent Architecture for Intelligent Building,Sensing and Control. International Sensor ReviewJournal, 132.

Szell, M. (2003). Intelligent Building, IntegratingDesign. Periodica PolytechnicalSer.CIV.ENG(47), No.1, 49.

Vidler, A. (2000). Warped Space. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press,176.

Wigginton, M., & Harris, J. (2002). IntelligentSkins. Oxford: Architectural Press,171

Zellner, P. (1999). Hybrid Space, New forms indigital architecture. London: Thames and HudsonPublications.

![Pt1286633[Anshuman Arya] Final Pptmaking of Piston](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/563dbab7550346aa9aa776ea/pt1286633anshuman-arya-final-pptmaking-of-piston.jpg)