Resources The Frist Center presents American Anthem

Transcript of Resources The Frist Center presents American Anthem

Resources for Teacher and Students Books

Websites

American Folk Art American Folk Art Museum, New York, New York www.folkartmuseum.org Folk Art Society of American www.folkart.org American History Timelines American Memory Timeline, Library of Congress Learning Page (interactive) http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/ American History Timeline, Smithsonian Institute (interactive) http://www.si.edu/resource/faq/nmah/timeline.htm

Teacher Workshop

Learn more about American Folk Art at an interdisciplinary teacher workshop. Teachers of all subjects, K–12, are welcome. Space is limited so please register early. $15 for members $20 for non-members Thursday, February 10 OR Saturday, February 12, 8. To register for a teacher workshop or to obtain information about school tours, visit www.fristcenter.org or call (615) 744-3247.

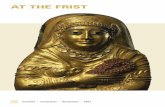

Archangel Gabriel Inn Sign, 1810–35 For 150 years, this figure of the Archangel Gabriel was a well-known local landmark, mounted above the entry to a building that served as a post office and general store before it became the Angel Inn. It was not uncommon for a figure of Gabriel, in Christian tradition the herald of the Second Coming, to appear as a weathervane on the steeples of churches. Secular settings, such as the Angel Inn, then located on a busy stagecoach route, were also known.

Frist Center for the Visual Arts January 21– May 1, 2005

The Frist Center presents

American Anthem A teacher’s guide to selected works from the exhibition. Featuring historic and contemporary artwork, American Anthem DiscoveryTours and Story Tours encourage students to explore symbols of liberty, ingenuity, and refuge that are embedded in American folk art. This guide is designed to help prepare students for their visit.

A handprint marks topics for discussion and activities for students.

What’s in This Teacher’s Guide? American Anthem Introduction, page 1 “Learning to Look” and Curriculum Connections, page 2 Art in the Home, pages 3–4 Quilt Stories, pages 5–6 Patriotism and Politics, pages 7–8 Changing Worlds, pages 9–10 Twentieth-Century Folk Art, pages 11–14 Reproducible Activity Sheets, pages 15–18 Resources, back cover

Resources Exhibition Catalogue

Anderson, Brooke Davis, and Stacy C. Hollander. American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 2001.

Websites

American Folk Art Museum, New York www.folkartmuseum.org Folk Art Society of America www.folkart.org

American Memory Timeline Library of Congress Learning Page (interactive) http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/ American History Timeline Smithsonian Institute (interactive) http://www.si.edu/resource/faq/nmah/timeline.htm

Teacher Workshop

Learn more about American Folk Art at an interdisciplinary teacher workshop. Teachers of all subjects, K–12, are welcome. Space is limited so please register early. $15 for members and $20 for non-members Thursday, February 10 OR Saturday, February 12 8:30 a.m.–3:30 p.m. To register for a teacher workshop or to obtain information about school tours, visit www.fristcenter.org or call (615) 744-3247.

Unidentified artist, Guilford Center Chenango County, New York Archangel Gabriel Inn Sign, 1810–35 Paint on wood; 24 x 46 1/2 x 18 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum New YorkGift of Alice M. Kaplan, trustee, 1997–1989, Museum of American Folk Art, 2001.3.1; Photo by John Parnell

For 150 years, this figure of the Archangel Gabriel was a well-known local landmark, mounted above the entry to a building that served as a post office and general store before it became the Angel Inn. It was not uncommon for a figure of Gabriel, in Christian tradition theherald of the Second Coming, to appear as a weathervane on the steeples of churches. Secular settings, such as the Angel Inn, then located on a busy stagecoach route, were also known. COVER: All artworks collection American Folk Art Museum, New York © 2005 except detail first row, 3rd from left: Art © Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum has been organized by the American Folk Art Museum, New York. American Anthem is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc.

2005 Platinum Sponsor: 2005 Gold Sponsor:

919 Broadway, Nashville, TN 37203

American Anthem includes more than 130 examples of folk art created for a variety of reasons. The exhibition first focuses on the nation’s early years, when functional objects were embellished with decorative elements in an effort to beautify homes. It then examines ways in which artists celebrated national events and documented important cultural changes. Finally, American Anthem explores contemporary folk art, sometimes called visionary art, outsider art, or art brut, which often contains spiritual and psychological dimensions.

American Anthem

Preparing for your visit… The American Anthem teaching packet was designed with teachers’ needs in mind, and we hope you will find it helpful in preparing students for their visit and in follow up study. The guide opens with a series of questions (“Learning to Look”) that encourage students to look closely and discuss historic and contemporary works of art from the exhibition. Each of the following sections include a timeline, which provides historical context, and a narrative about the artwork, which can be incorporated into class discussion or given as a reading assignment to older students. Designed to be adaptable to all ages, “Making a Connection” activities allow students to reflect and relate the art and ideas to their own lives and experiences. Each activity is accompanied by color reproductions and some have reproducible sheets.

UPPER RIGHT: Attributed to Sturtevant J. Hamblin (active 1837–1856), probably Massachusetts Sea Captain, ca. 1845 Oil on canvas; 27 1/8 x 22 ¼ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of Robert Bishop, 1992.10.2 Photo by John Parnell LOWER LEFT: Unidentified artist, New England Sea Serpent Weathervane, ca. 1850 Paint on wood with iron; 16 1/4 x 23 1/4 x 1 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.13 Photo by John Parnell

UPPER RIGHT: Bessie Harvey (1929–1994), Alcoa, Blount County, Tennessee Faces of Africa I, 1994 Paint on wood with wood putty, shells,and marbles; 33 x 28 x 17 in. American Folk Art Museum, New York Blanchard-Hill Collection, gift of M. Anne Hill and Edward V. Blanchard Jr., 1998.10.24; Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Gregory “Mr. Imagination” Warmack (b. 1948), Chicago, Illinois Button Tree, 1990–92 Wood and cement with buttons, bottle caps, and nails 56 x 34 x 60 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of the artist, 2000.13.1 Photo by John Parnell

Compare Two Works of Art What do you see (shapes, colors, textures, etc.)? What did you learn about the artist and the work? What do you think about these two works of art? In the overlapping parts of the circles, write similarities of the works, and in the part of the circles that do not overlap, write the unique characteristics and differences of each work.

Faces of Africa I Button Tree

1 18

Reproducible Activity Sheet

Curriculum Connections American Anthem Discovery Tours and Story Tours support the Tennessee Curriculum Frameworks by introducing themes that are relevant to visual arts, language arts, and social studies curricula. Specific standards are addressed at age-appropriate levels. An example is shown below. You may view connections for all grade levels (K–12) at www.fristcenter.org.

Example: Sixth Grade Visual Arts 4.0 Historical/Cultural Relationship.The student will speculate on how factors of time and place give meaning or function to a work of art from a variety of cultures, times, and places. 5.0 Reflection and Assessment. The student will understand and apply visual arts vocabulary when observing, describing, analyzing, and interpreting works of art 5.0 Reflection and Assessment. The student will describe and interpret different ways that human experience is reflected in contemporary and historic works of art.

Language Arts 1.0 Reading. (6.1.tpi.8.) The student will make creative responses to texts. 1.0 Reading. (6.1.tpi.10.) The student will express personal reactions to texts. 1.0 Reading. (6.1.tpi.27.) The student will use content specific vocabulary. 2.0 Writing. (6.2.tpi.14.) The student will compare and respond to questions from all content areas. 2.0 Writing. (6.2.tpi.16.) The student will write personal reflections on experiences and events.

Social Studies 1.0 Culture (6.1.tpi.6.) The student will compare various formsof jewelry, art, music, and literature among historical periods. 1.0 Culture (6.1.tpi. 13.) The student will create a piece of artwork based on a historical example. 6.0 Individuals, Groups, and Interactions (6.6.tpi.7.) The student will analyze differing communities' perception of beauty.

Encourage students to look closely at each work of art and consider the following questions:

• The Artist: Who created the work? When did the artist begin making art? Do you think he/she had some sort of formal art training? Why or why not? How and where might the artist have gained his/her skills?

• Purpose: Why did the artist create the work? Does the work of art serve a specific purpose or function? If so, how was it used or where might it have been displayed? If the object is functional, why might its creator have decided to decorate it?

• Ideas: What is the subject matter of the work? Does the work of art reflect the artist’s ideas or beliefs? If so, how?

• Stories: Does the work tell a story about the artist’s personal life or important national events? What objects, props, or symbols does the artist include to help tell the story?

• Materials: What materials did the artist use to create the work of art? Where do you think he/she found these materials? Why do you think the artist chose to use them?

• Techniques: What techniques did the artist use to create the object? Did he/she need any special training, skills, or materials to make the object?

Learning to Look. Looking to Learn. Farm vs. Factory

Look closely at each work and compare the farm and factory. Identify thecharacteristics of the landscapes, the style and purpose of the buildings, the modes of transportation, etc. Record your findings below.

Land Buildings

Transportation

Other Findings

Land Buildings

Transportation

Other Findings

The Residence of Lemuel Cooper, 1879 Paul A. Seifert (1840–1921), Plain, Sauk County, Wisconsin Watercolor, oil, tempera, ink, and pencil on paper; 21 7/8 x 28 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.26 Photo by John Parnell

Unidentified artist, signed “AJH/77” Oswego Starch Factory, possibly 1877 Oswego, Oswego County, New York Watercolor and ink on paper; 36 1/8 x 53 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.16.

217

Reproducible Activity Sheet

After the Revolutionary War, the democracies of ancient Greece and Rome provided the model for the new American republic, and also inspired an aesthetic revolution in architecture, furnishings, clothing, and hairstyles. By the early nineteenth century, schoolgirl needlework, stenciled chairs, and handmade memorials reflecting neoclassical symbols of liberty and virtue frequently held places of honor in people’s homes. Portraits were also an important means of parlor decoration in the early nineteenth century. Many portrait artists were former sign- or housepainters with no formal art training. Traveling portrait painters such as John S. Blunt were hired to create likenesses of wealthy landowners and merchants, using a plain and simple painting style reflecting republican values.

Miss Francis A. Motley, 1830–33 In this portrait attributed to Blunt, Francis Motley represents the virtues associated with the nineteenth-century notion of true womanhood. The coral necklace, tasseled blue drawstring purse, and flowers symbolize feminine characteristics. The sewing basket on her lap is a reminder that skill with a needle was a necessary accomplishment for young women. A small card with the name “Francis A. Motley” sits on the table, announcing the sitter’s identity.

Liberty Needlework, 1808 In the 1800s young girls often attended schools where they learned domestic arts, including needlework. In this needlework project by Lucina Hudson, Liberty is represented as a young girl with tightly curled hair holding a liberty pole. On the pole, a colorful flag flies beneath a pileus.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Art in the Home

Attributed to John S. Blunt (1798–1835), probably Maine, Massachusetts, or New Hampshire. Miss Frances A. Motley, 1830–33 Oil on canvas; 35 3/8 x 29 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Promised gift of Barbara and David Krashes, P7.1999.1 Photo by Cheryl Richards Coral necklace: In the past, coral necklaces were thought to protect their wearers from evil and sickness. Pileus: a close-fitting cap that was worn in ancient Rome. It symbolized liberty in neoclassical art.

Lucina Hudson (1787–?), South Hadley, Massachusetts. Liberty Needlework, 1808 Watercolor and silk thread on silk, with metallic thread and spangles, 18 x 16 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase with funds from the Jean Lipman Fellows,1996, 1996.9.1

My Family Album Quilt

Think of important events in your family’s history —maybe the birth of a sibling or a major move to another state far away from loved ones. How willyou tell your story (orstories) in a quilt? What symbols and colors will you use to represent each event and family member? Design your own family album quilt, and write a narrative to accompany it.

My quilt tells a story about…

16

Reproducible Activity Sheet

Think of a person who is special to you—maybe a family member or close friend. What qualities does that person exemplify? What are his/her hobbies and interests? Assemble a collection of photographs and small found objects that symbolize important aspects of that person. Arrange and attach the items to a solid form or small container. Write a label for your work describing the person for whom it was created and the materials that were used.

Memorial to Washington, early nineteenth century George Washington’s death in 1799, the first nationwide emotional loss suffered by the young country, shocked Americans. People mourned by holding memorial services or by fashioning commemorative objects to place in their homes. This small handmade memorial is in the form of an urn placed on a plinth, a neoclassical motif widely used in the decorative arts of the time. Ironically, much of the production of objects memorializing America’s early heroes originated in England and were later copied by professional and amateur artists in America. Memorials to Washington like this one were still being created by schoolgirls through the late 1820s.

Making a Connection Honor a Loved One

Think of a person who is special to you—maybe a family member or close friend. What qualities does that person exemplify? What are his/her hobbies and interests? Assemble a collection of photographs and small found objects that symbolize important aspects of that person. Arrange and attach the items to a solid form or small container. Write a label for your work describing the person for whom it was created and the materials that were used.

Refer to the activity sheet on page 15.

Plinth: a square block beneath a column, pedestal, or statue.

Star from REcollection Community Art Project, led by artist Sherri Warner Hunter. Community members contributed to the project by using found objects, mementos, and photographs to create stars that honor loved ones.

Unidentified artist, eastern United States. Memorial to Washington, early nineteenth century. Ink, mica flakes, and mezzotint engravings on paper with applied gold paper, mounted on wood form 4 ¾ x 1 ¾ x 1 ¾ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York. Gift of Nancy Green Karlins and Mark Thoman in honor of Robert Evans Green, 1999.9. Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Star from REcollection: Community Art Project, led by artist Sherri Warner Hunter. Community members contributed to the project by using found objects, mementos, and photographs to create stars that honor loved ones.

Honor a Loved One

My Object Honors…

415

Reproducible Activity Sheet

By 1840, with the growth of the textile industry and widespread availability of fabric, quiltmaking became a creative and often social outlet for American women. A wide range of quilt patterns was dispersed across the country as families moved. Although quilts provided warmth and beauty for the home, many were also made to commemorate special occasions. Brides-to-be sewed quilts for their hope chests, grieving mothers made mourning quilts to memorialize loved ones, and neighbors gave friendship quilts as mementos to families moving westward. Many such quilts became treasured heirlooms, reflecting the personalities of their makers and preserving the stories they told of friends and family. Reiter Family Album Quilt, ca. 1891–92, reassembled 1976 In 1885 Liebe Gross Friedman, a Jewish woman from Slovakia, sent her young daughter Katie to America to escape a difficult life. Katie married in 1890 and moved to Pennsylvania, where she was joined a year later by her mother, sister, and brother. Later that year, Katie’s baby son died, and shortly after, her brother drowned in the Youghiogheny River. Liebe and Katie made the quilt as an expression of their grief. This quilt is comprised of sixteen embellished quilt blocks and bordered by blocks that complete the overall design. The symbolic American eagle is placed prominently in one square. Two black horse figures are thought to symbolize the two dead children, and are a play on the family name, Reiter, which means “rider” in German.

Visionary art is a term often used to describe work inspired by religious faith, and includes lively expressions of spirituality in traditional and contemporary forms. America’s history of diverse religious traditions may be seen in Southern evangelical paintings, scenes from the Jewish Bible, and African-inspired protective yard art. These works reflect the need to capture the spiritual in visual form, and celebrate the quest for religious freedom that inspired the settlement of America.

Faces of Africa I, 1994 After her mother’s death in 1974, Bessie Harvey found comfort in creating sculptures from roots and pieces of wood. Her works may represent personal stories, Bible stories, or figures from African American history and folklore. In Faces of Africa I, Bessie Harvey placed a human face into the roots of a tree, using black spraypaint, wood putty, white shells, and marbles. This is one of many sculptures Harvey created to free the spirits and souls she believed were held captive in trees. She once said, “I see African people in the trees and in the roots. I frees them.”

Making a Connection Compare Two Works of Art

Look closely and compare Button Tree and Faces of Africa I. Consider what you see, what you’ve learned, and what you think about the works. Record the similarities and differences of the works on the diagram. Refer to the activity sheet on page 18.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Quilt Stories

DETAILS and RIGHT: Katie Friedman Reiter (1873–1942) and Liebe Gross Friedman (dates unknown), McKeesport, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Reiter Family Album Quilt, ca. 1891–92, reassembled 1976. Cotton and wool; 101 x 101 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York. Gift of Katherine Amelia Wine in honor of her grandmother Theresa Reiter Gross and the makers of the quilt, her great-grandmother Katie Friedman Reiter and her great-great-grandmother Liebe Gross Friedman, and on behalf of a generation of cousins: Sydney Howard Reiter, Penelope Breyer Tarplin, Jonnie Breyer Stahl, Susan Reiter Blinn, Benjamin Joseph Gross, and Leba Gross Wine, 2000.2.1. Photo by John Parnell

Bessie Harvey (1929–1994) Alcoa, Blount County, Tennessee Faces of Africa I, 1994 Paint on wood with wood putty, shells, and marbles 33 x 28 x 17 in. American Folk Art Museum, New York Blanchard-Hill Collection, gift of M. Anne Hill and Edward V. Blanchard Jr., 1998.10.24 Photo by Gavin Ashworth

14

After World War II, the terms art brut (French for “raw art”), visionary art, and outsider art denoted drawings, paintings, and sculptures produced by people at the margins of society, including the homeless, prisoners, and psychiatric patients. Although these labels have been a source of misunderstanding in the ensuing years, certain characteristics of contemporary self-taught artists unite them. Many begin producing art late in life and work only with materials that are readily available. Some offer deeply personal, sometimes visionary imagery of the world around them, while others express inner emotions and fantasies.

Making a Connection My Family Album Quilt

Think of important events in your family’s history —maybe the birth of a sibling or a major move to another state far away from loved ones. How will you tell your story in a quilt? What symbols and colors will you use to represent each event and family member? Design your own family album quilt, and write a narrative to accompany it. Refer to the activity sheet on page 16.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Twentieth-Century Folk Art

Button Tree, 1990–92 After Gregory Warmack was shot in an attempted robbery in 1978, he decided to become an artist. Calling himself “Mr. Imagination,” Warmack, who had always made art, enjoyed a new surge of creativity. Like folk artist Bessie Harvey, Warmack rescues dead limbs and transforms them into works of art. Button Tree is set in a base covered with bottle caps and covered with buttons nailedto the limb in a style similar to some Central African wooden sculptures, called minkisi. (note: nkisi is singular; minkisi is plural) Gregory “Mr. Imagination” Warmack (b. 1948), Chicago, Illinois Button Tree, 1990–92 Wood and cement with buttons, bottle caps, and nails; 56 x 34 x 60 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of the artist, 2000.13.1 Photo by John Parnell

6

American folk art often conveys patriotic themes, whether by celebrating national events, such as the installation of the Statue of Liberty, or observing a nation at war. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 was met with patriotic zeal by both Northerners and Southerners. Some artisans expressed their national pride in their art while others created handicrafts that remind us even today of this painful chapter in our nation’s history. Statue of Liberty Cabinet, ca. 1886–90 The Statue of Liberty, dedicated on October 28, 1886, is perhaps the best known symbol of America. This cabinet by Titus Albrecht celebrates the Statue of Liberty by perching her silhouette triumphantly atop an ornately carved cascade of filigree woodwork. Completing the patriotic theme, the desktop features an eagle with spread wings standing on an American flag, holding three arrows and an olive branch in its talons.

Cow Jump Over the Mone, 1978 Nellie Mae Rowe was an African American woman born in the segregated South at the turn of the century. In 1948 she turned her full attention to making art, decorating her home in Vinings, Georgia. She worked with readily available materials, such as colored pencils, felt-tip pens, and paper for her drawings, and Styrofoam food trays, wallpaper sample books, wood, and chewing gum for her sculptures. In this work, Nellie Mae Rowe depicts herself as a cow jumping over the moon, which may be read as a metaphor for overcoming (or “jumping over”) difficult circumstances.

Making a Connection A Metaphor for Me

Think of an animal* that could stand as a metaphor for you. When choosing, consider the characteristics of various animals. For example, saying that someone is a snake may imply that the person is sly or sneaky. Create a drawing based on the metaphor you have chosen. Have your classmates guess what you were trying to express about yourself in the work.

Segregation: the practice of separating people by race, ethnicity, or religion. Metaphor: The use of a word, phrase, or image to represent somebody or something.

* For middle and high school students: Think about an event or occurrence that has deeply affected you. Howmight you represent that experience metaphorically in a work of art?

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Patriotism and Politics

Titus Albrecht (or Tidus Albrech) (dates unknown), vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri. Statue of Liberty Cabinet, ca. 1886–90. Wood with cutouts and paint decoration; 77 3/4 x 30 3/8 x 21 1/8 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York. Gift of the Hirschhorn Foundation, 1997.6.2. Photo by David Stansbury

Nellie Mae Rowe (1900–1982), Vinings, Cobb County, Georgia Cow Jump over the Mone, 1978 Colored pencil, crayon, and pencil on paper; 19 1/2 x 25 ¼ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of Judith Alexander, 1997.10.1 Photo by Gavin Ashworth

12

By the twentieth century, as mechanical processes rendered most handmade products obsolete, folk art became less a reflection of communal interests and more the expression of individual artists, primarily painters and sculptors. As self-taught artists gained the attention of the art world, new terminology expanded the definition of folk art. In the first half of the century, naïve and primitive described painters like Grandma Moses, who were essentially interested in recording recognizable objects in the world around them, and did so with untutored simplicity, originality, and nostalgia that offered wide appeal in the rapidly changing culture. Mother Cat with Kittens, 1941 After coming to the United States from eastern Europe at the turn of the century, Morris Hirshfield settled in Brooklyn, New York, where he worked in the garment business. He retired in 1937 and began to paint. In his lifetime, Hirschfield completed seventy-six canvases of mostly women and animals, painted in a flat style with bold patterns, bright colors, and fabric-like textures.

Uncle Sam Riding a Bicycle Whirligig, ca. 1880–1920 In the late nineteenth century, an unidentified artist in upstate New York carved the Uncle Sam Riding a Bicycle Whirligig, a wooden wind toy that is now an icon of American folk art. The patriotic figure of Uncle Sam is based on an actual man, Samuel Wilson, whose business supplied meat to the troops during the War of 1812. His top hat and striped pants are based on the Revolutionary War figure of Yankee Doodle. When the wind turns the front propeller of this whirligig, Uncle Sam pedals a high-wheeler. The whirligig was found in upstate New York, near Canada, which may explain the presence of the British flag, the Union Jack, opposite the Stars and Stripes.

Making a Connection A Whimsical Whirligig

Visit ArtQuest’s new Exploring Exhibitions station or arrange a class visit to the art studios, where students will be able to construct their own whirligigs inspired by American Anthem. Reservations required. To schedule, call the Tour Coordinator at (615) 744-3247.

Whirligig: a wooden wind toy that spins and turns on a pivot when the wind blows. High-wheeler: an English bicycle with a large front wheel and small back wheel, made popular at the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Twentieth-Century Folk Art

Unidentified artist, probably New York State Uncle Sam Riding a Bicycle Whirligig, ca. 1880–1920 Paint on wood with metal, 37 x 55 ½ x 11 in. American Folk Art Museum, New York Promised bequest of Dorothea and Leo Rabkin, P2.1981.6; Photo by John Parnell

Morris Hirshfield (1872–1946), Brooklyn, New York Mother Cat with Kittens, 1941 Oil on canvas 24 x 36 in. Gift of Patricia L. and Maurice CA. Thompson Jr. and purchase with funds from the Jean Lipman Fellows, 1998, 1998.5.1 Art © Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY Photo by Charles Bechtold

8

After the Civil War, industrialization brought widespread changes in American culture to which folk artists responded through their work. Topographical views of a Wisconsin farm and a New York factory town, both produced in the late 1870s, underscore the emerging shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy. Artists contemplated the rapid advances in transportation with images of high-wheelers, automobiles, and flying machines. They also carved carousel horses and curious trade figures to meet the growing appetite for amusement and leisure activities, and explored the intersections of art and science, as seen in Asa Ames’s Phrenological Head. The Residence of Lemuel Cooper, 1879 Westward expansion made land west of the Appalachians the leading food-producing area of the country. In 1879 Lemuel Cooper’s bountiful farm in Plain, Wisconsin, was painted by Paul Seifert. Seifert was a German immigrant who supported himself by selling flowers, vegetables, and fruit from his own gardens. He took great pleasure in depicting the regularity of Wisconsin farmscapes, and never accepted more than $2.50 for his works. The drawings were typically made using watercolor, oil, and tempera on colored paper, and sometimes included metallic paints to highlight elements such as weathervanes.

Oswego Starch Factory, possibly 1877 With the mechanization of the Civil War, America entered the Industrial Revolution, with machine-manufactured and mass-produced goods replacing handmade items. Scenes of progress were captured in prints and other publications. Artists depicted factories, cities, and towns, sometimes using aerial perspective that provided bird’s-eye views and emphasized details of streets and individual buildings. This large-scale, hand-painted version of Thomas Kingsford’s starch factory complex in Oswego, New York, shows the starch factory, a box factory, a machine shop, a carpentry shop, storehouses and other outbuildings, and the factory’s own fire company.

Making a Connection Farm vs. Factory

Look closely and compare The Residence of Lemuel Cooper and the Oswego Starch Factory. Identify the characteristics of the landscapes, the style and purpose of the buildings, the modes of transportation, etc. Record your findings in the Observation Diary. Refer to the activity sheet on page 17. Read personal accounts of residents describing city life and rural life in the late nineteenth century on the Library of Congress Learning Page, “Rise of Industrial America.””http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/riseind/riseof.html.

High-wheeler: an English bicycle with a large front wheel and small back wheel, made popular at the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876. Weathervane: a device commonly made of metal or wood that is placed on poles atop buildings, barns, and houses. When the wind blows, it turns on a pivot revealing the wind’s direction. The Residence of Lemuel Cooper, 1879 Paul A. Seifert (1840–1921), Plain, Sauk County, Wisconsin Watercolor, oil, tempera, ink, and pencil on paper; 21 7/8 x 28 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.26 Photo by John Parnell

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Changing Worlds

Unidentified artist, signed “AJH/77” Oswego Starch Factory, possibly 1877 Oswego, Oswego County, New York Watercolor and ink on paper; 36 1/8 x 53 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.16 Photo by John Parnell Attributed to Asa Ames (1824–1851), Evans, ErieCounty, New York Phrenological Head ca. 1850 Paint on wood 16 3/8 x 13 x 7 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Bequest of Jeanette Virgin, 1981.24.1 Photo by John Parnell

10

After the Civil War, industrialization brought widespread changes in American culture to which folk artists responded through their work. Topographical views of a Wisconsin farm and a New York factory town, both produced in the late 1870s, underscore the emerging shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy. Artists contemplated the rapid advances in transportation with images of high-wheelers, automobiles, and flying machines. They also carved carousel horses and curious trade figures to meet the growing appetite for amusement and leisure activities, and explored the intersections of art and science, as seen in Asa Ames’s Phrenological Head. The Residence of Lemuel Cooper, 1879 Westward expansion made land west of the Appalachians the leading food-producing area of the country. In 1879 Lemuel Cooper’s bountiful farm in Plain, Wisconsin, was painted by Paul Seifert. Seifert was a German immigrant who supported himself by selling flowers, vegetables, and fruit from his own gardens. He took great pleasure in depicting the regularity of Wisconsin farmscapes, and never accepted more than $2.50 for his works. The drawings were typically made using watercolor, oil, and tempera on colored paper, and sometimes included metallic paints to highlight elements such as weathervanes.

Oswego Starch Factory, possibly 1877 With the mechanization of the Civil War, America entered the Industrial Revolution, with machine-manufactured and mass-produced goods replacing handmade items. Scenes of progress were captured in prints and other publications. Artists depicted factories, cities, and towns, sometimes using aerial perspective that provided bird’s-eye views and emphasized details of streets and individual buildings. This large-scale, hand-painted version of Thomas Kingsford’s starch factory complex in Oswego, New York, shows the starch factory, a box factory, a machine shop, a carpentry shop, storehouses and other outbuildings, and the factory’s own fire company.

Making a Connection Farm vs. Factory

Look closely and compare The Residence of Lemuel Cooper and the Oswego Starch Factory. Identify the characteristics of the landscapes, the style and purpose of the buildings, the modes of transportation, etc. Record your findings in the Observation Diary. Refer to the activity sheet on page 17. Read personal accounts of residents describing city life and rural life in the late nineteenth century on the Library of Congress Learning Page, “Rise of Industrial America.””http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/riseind/riseof.html.

High-wheeler: an English bicycle with a large front wheel and small back wheel, made popular at the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876. Weathervane: a device commonly made of metal or wood that is placed on poles atop buildings, barns, and houses. When the wind blows, it turns on a pivot revealing the wind’s direction. The Residence of Lemuel Cooper, 1879 Paul A. Seifert (1840–1921), Plain, Sauk County, Wisconsin Watercolor, oil, tempera, ink, and pencil on paper; 21 7/8 x 28 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.26 Photo by John Parnell

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Changing Worlds

Unidentified artist, signed “AJH/77” Oswego Starch Factory, possibly 1877 Oswego, Oswego County, New York Watercolor and ink on paper; 36 1/8 x 53 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.16 Photo by John Parnell Attributed to Asa Ames (1824–1851), Evans, ErieCounty, New York Phrenological Head ca. 1850 Paint on wood 16 3/8 x 13 x 7 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Bequest of Jeanette Virgin, 1981.24.1 Photo by John Parnell

10

By the twentieth century, as mechanical processes rendered most handmade products obsolete, folk art became less a reflection of communal interests and more the expression of individual artists, primarily painters and sculptors. As self-taught artists gained the attention of the art world, new terminology expanded the definition of folk art. In the first half of the century, naïve and primitive described painters like Grandma Moses, who were essentially interested in recording recognizable objects in the world around them, and did so with untutored simplicity, originality, and nostalgia that offered wide appeal in the rapidly changing culture. Mother Cat with Kittens, 1941 After coming to the United States from eastern Europe at the turn of the century, Morris Hirshfield settled in Brooklyn, New York, where he worked in the garment business. He retired in 1937 and began to paint. In his lifetime, Hirschfield completed seventy-six canvases of mostly women and animals, painted in a flat style with bold patterns, bright colors, and fabric-like textures.

Uncle Sam Riding a Bicycle Whirligig, ca. 1880–1920 In the late nineteenth century, an unidentified artist in upstate New York carved the Uncle Sam Riding a Bicycle Whirligig, a wooden wind toy that is now an icon of American folk art. The patriotic figure of Uncle Sam is based on an actual man, Samuel Wilson, whose business supplied meat to the troops during the War of 1812. His top hat and striped pants are based on the Revolutionary War figure of Yankee Doodle. When the wind turns the front propeller of this whirligig, Uncle Sam pedals a high-wheeler. The whirligig was found in upstate New York, near Canada, which may explain the presence of the British flag, the Union Jack, opposite the Stars and Stripes.

Making a Connection A Whimsical Whirligig

Visit ArtQuest’s new Exploring Exhibitions station or arrange a class visit to the art studios, where students will be able to construct their own whirligigs inspired by American Anthem. Reservations required. To schedule, call the Tour Coordinator at (615) 744-3247.

Whirligig: a wooden wind toy that spins and turns on a pivot when the wind blows. High-wheeler: an English bicycle with a large front wheel and small back wheel, made popular at the Philadelphia Centennial of 1876.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Twentieth-Century Folk Art

Unidentified artist, probably New York State Uncle Sam Riding a Bicycle Whirligig, ca. 1880–1920 Paint on wood with metal, 37 x 55 ½ x 11 in. American Folk Art Museum, New York Promised bequest of Dorothea and Leo Rabkin, P2.1981.6; Photo by John Parnell

Morris Hirshfield (1872–1946), Brooklyn, New York Mother Cat with Kittens, 1941 Oil on canvas 24 x 36 in. Gift of Patricia L. and Maurice CA. Thompson Jr. and purchase with funds from the Jean Lipman Fellows, 1998, 1998.5.1 Art © Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY Photo by Charles Bechtold

8

American folk art often conveys patriotic themes, whether by celebrating national events, such as the installation of the Statue of Liberty, or observing a nation at war. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 was met with patriotic zeal by both Northerners and Southerners. Some artisans expressed their national pride in their art while others created handicrafts that remind us even today of this painful chapter in our nation’s history. Statue of Liberty Cabinet, ca. 1886–90 The Statue of Liberty, dedicated on October 28, 1886, is perhaps the best known symbol of America. This cabinet by Titus Albrecht celebrates the Statue of Liberty by perching her silhouette triumphantly atop an ornately carved cascade of filigree woodwork. Completing the patriotic theme, the desktop features an eagle with spread wings standing on an American flag, holding three arrows and an olive branch in its talons.

Cow Jump Over the Mone, 1978 Nellie Mae Rowe was an African American woman born in the segregated South at the turn of the century. In 1948 she turned her full attention to making art, decorating her home in Vinings, Georgia. She worked with readily available materials, such as colored pencils, felt-tip pens, and paper for her drawings, and Styrofoam food trays, wallpaper sample books, wood, and chewing gum for her sculptures. In this work, Nellie Mae Rowe depicts herself as a cow jumping over the moon, which may be read as a metaphor for overcoming (or “jumping over”) difficult circumstances.

Making a Connection A Metaphor for Me

Think of an animal* that could stand as a metaphor for you. When choosing, consider the characteristics of various animals. For example, saying that someone is a snake may imply that the person is sly or sneaky. Create a drawing based on the metaphor you have chosen. Have your classmates guess what you were trying to express about yourself in the work.

Segregation: the practice of separating people by race, ethnicity, or religion. Metaphor: The use of a word, phrase, or image to represent somebody or something.

* For middle and high school students: Think about an event or occurrence that has deeply affected you. Howmight you represent that experience metaphorically in a work of art?

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Patriotism and Politics

Titus Albrecht (or Tidus Albrech) (dates unknown), vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri. Statue of Liberty Cabinet, ca. 1886–90. Wood with cutouts and paint decoration; 77 3/4 x 30 3/8 x 21 1/8 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York. Gift of the Hirschhorn Foundation, 1997.6.2. Photo by David Stansbury

Nellie Mae Rowe (1900–1982), Vinings, Cobb County, Georgia Cow Jump over the Mone, 1978 Colored pencil, crayon, and pencil on paper; 19 1/2 x 25 ¼ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of Judith Alexander, 1997.10.1 Photo by Gavin Ashworth

12

After World War II, the terms art brut (French for “raw art”), visionary art, and outsider art denoted drawings, paintings, and sculptures produced by people at the margins of society, including the homeless, prisoners, and psychiatric patients. Although these labels have been a source of misunderstanding in the ensuing years, certain characteristics of contemporary self-taught artists unite them. Many begin producing art late in life and work only with materials that are readily available. Some offer deeply personal, sometimes visionary imagery of the world around them, while others express inner emotions and fantasies.

Making a Connection My Family Album Quilt

Think of important events in your family’s history —maybe the birth of a sibling or a major move to another state far away from loved ones. How will you tell your story in a quilt? What symbols and colors will you use to represent each event and family member? Design your own family album quilt, and write a narrative to accompany it. Refer to the activity sheet on page 16.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Twentieth-Century Folk Art

Button Tree, 1990–92 After Gregory Warmack was shot in an attempted robbery in 1978, he decided to become an artist. Calling himself “Mr. Imagination,” Warmack, who had always made art, enjoyed a new surge of creativity. Like folk artist Bessie Harvey, Warmack rescues dead limbs and transforms them into works of art. Button Tree is set in a base covered with bottle caps and covered with buttons nailedto the limb in a style similar to some Central African wooden sculptures, called minkisi. (note: nkisi is singular; minkisi is plural) Gregory “Mr. Imagination” Warmack (b. 1948), Chicago, Illinois Button Tree, 1990–92 Wood and cement with buttons, bottle caps, and nails; 56 x 34 x 60 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of the artist, 2000.13.1 Photo by John Parnell

6

By 1840, with the growth of the textile industry and widespread availability of fabric, quiltmaking became a creative and often social outlet for American women. A wide range of quilt patterns was dispersed across the country as families moved. Although quilts provided warmth and beauty for the home, many were also made to commemorate special occasions. Brides-to-be sewed quilts for their hope chests, grieving mothers made mourning quilts to memorialize loved ones, and neighbors gave friendship quilts as mementos to families moving westward. Many such quilts became treasured heirlooms, reflecting the personalities of their makers and preserving the stories they told of friends and family. Reiter Family Album Quilt, ca. 1891–92, reassembled 1976 In 1885 Liebe Gross Friedman, a Jewish woman from Slovakia, sent her young daughter Katie to America to escape a difficult life. Katie married in 1890 and moved to Pennsylvania, where she was joined a year later by her mother, sister, and brother. Later that year, Katie’s baby son died, and shortly after, her brother drowned in the Youghiogheny River. Liebe and Katie made the quilt as an expression of their grief. This quilt is comprised of sixteen embellished quilt blocks and bordered by blocks that complete the overall design. The symbolic American eagle is placed prominently in one square. Two black horse figures are thought to symbolize the two dead children, and are a play on the family name, Reiter, which means “rider” in German.

Visionary art is a term often used to describe work inspired by religious faith, and includes lively expressions of spirituality in traditional and contemporary forms. America’s history of diverse religious traditions may be seen in Southern evangelical paintings, scenes from the Jewish Bible, and African-inspired protective yard art. These works reflect the need to capture the spiritual in visual form, and celebrate the quest for religious freedom that inspired the settlement of America.

Faces of Africa I, 1994 After her mother’s death in 1974, Bessie Harvey found comfort in creating sculptures from roots and pieces of wood. Her works may represent personal stories, Bible stories, or figures from African American history and folklore. In Faces of Africa I, Bessie Harvey placed a human face into the roots of a tree, using black spraypaint, wood putty, white shells, and marbles. This is one of many sculptures Harvey created to free the spirits and souls she believed were held captive in trees. She once said, “I see African people in the trees and in the roots. I frees them.”

Making a Connection Compare Two Works of Art

Look closely and compare Button Tree and Faces of Africa I. Consider what you see, what you’ve learned, and what you think about the works. Record the similarities and differences of the works on the diagram. Refer to the activity sheet on page 18.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Quilt Stories

DETAILS and RIGHT: Katie Friedman Reiter (1873–1942) and Liebe Gross Friedman (dates unknown), McKeesport, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Reiter Family Album Quilt, ca. 1891–92, reassembled 1976. Cotton and wool; 101 x 101 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York. Gift of Katherine Amelia Wine in honor of her grandmother Theresa Reiter Gross and the makers of the quilt, her great-grandmother Katie Friedman Reiter and her great-great-grandmother Liebe Gross Friedman, and on behalf of a generation of cousins: Sydney Howard Reiter, Penelope Breyer Tarplin, Jonnie Breyer Stahl, Susan Reiter Blinn, Benjamin Joseph Gross, and Leba Gross Wine, 2000.2.1. Photo by John Parnell

Bessie Harvey (1929–1994) Alcoa, Blount County, Tennessee Faces of Africa I, 1994 Paint on wood with wood putty, shells, and marbles 33 x 28 x 17 in. American Folk Art Museum, New York Blanchard-Hill Collection, gift of M. Anne Hill and Edward V. Blanchard Jr., 1998.10.24 Photo by Gavin Ashworth

14

Think of a person who is special to you—maybe a family member or close friend. What qualities does that person exemplify? What are his/her hobbies and interests? Assemble a collection of photographs and small found objects that symbolize important aspects of that person. Arrange and attach the items to a solid form or small container. Write a label for your work describing the person for whom it was created and the materials that were used.

Memorial to Washington, early nineteenth century George Washington’s death in 1799, the first nationwide emotional loss suffered by the young country, shocked Americans. People mourned by holding memorial services or by fashioning commemorative objects to place in their homes. This small handmade memorial is in the form of an urn placed on a plinth, a neoclassical motif widely used in the decorative arts of the time. Ironically, much of the production of objects memorializing America’s early heroes originated in England and were later copied by professional and amateur artists in America. Memorials to Washington like this one were still being created by schoolgirls through the late 1820s.

Making a Connection Honor a Loved One

Think of a person who is special to you—maybe a family member or close friend. What qualities does that person exemplify? What are his/her hobbies and interests? Assemble a collection of photographs and small found objects that symbolize important aspects of that person. Arrange and attach the items to a solid form or small container. Write a label for your work describing the person for whom it was created and the materials that were used.

Refer to the activity sheet on page 15.

Plinth: a square block beneath a column, pedestal, or statue.

Star from REcollection Community Art Project, led by artist Sherri Warner Hunter. Community members contributed to the project by using found objects, mementos, and photographs to create stars that honor loved ones.

Unidentified artist, eastern United States. Memorial to Washington, early nineteenth century. Ink, mica flakes, and mezzotint engravings on paper with applied gold paper, mounted on wood form 4 ¾ x 1 ¾ x 1 ¾ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York. Gift of Nancy Green Karlins and Mark Thoman in honor of Robert Evans Green, 1999.9. Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Star from REcollection: Community Art Project, led by artist Sherri Warner Hunter. Community members contributed to the project by using found objects, mementos, and photographs to create stars that honor loved ones.

Honor a Loved One

My Object Honors…

415

Reproducible Activity Sheet

After the Revolutionary War, the democracies of ancient Greece and Rome provided the model for the new American republic, and also inspired an aesthetic revolution in architecture, furnishings, clothing, and hairstyles. By the early nineteenth century, schoolgirl needlework, stenciled chairs, and handmade memorials reflecting neoclassical symbols of liberty and virtue frequently held places of honor in people’s homes. Portraits were also an important means of parlor decoration in the early nineteenth century. Many portrait artists were former sign- or housepainters with no formal art training. Traveling portrait painters such as John S. Blunt were hired to create likenesses of wealthy landowners and merchants, using a plain and simple painting style reflecting republican values.

Miss Francis A. Motley, 1830–33 In this portrait attributed to Blunt, Francis Motley represents the virtues associated with the nineteenth-century notion of true womanhood. The coral necklace, tasseled blue drawstring purse, and flowers symbolize feminine characteristics. The sewing basket on her lap is a reminder that skill with a needle was a necessary accomplishment for young women. A small card with the name “Francis A. Motley” sits on the table, announcing the sitter’s identity.

Liberty Needlework, 1808 In the 1800s young girls often attended schools where they learned domestic arts, including needlework. In this needlework project by Lucina Hudson, Liberty is represented as a young girl with tightly curled hair holding a liberty pole. On the pole, a colorful flag flies beneath a pileus.

A Place in History Find what was happening in America around the time these works were created. Late 1700s to1800s Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Industrial Revolution 1790–1860 Civil War 1861–1865 Late 1800s to1900s The Progressive Era 1890–1913 World War I 1914–1918 The Great Depression 1929–1939 World War II 1941–1945 Vietnam War 1965–1973 2000 to Present World Trade Center Terrorist Attack 2001 Smithsonian Institute American History Timeline

Art in the Home

Attributed to John S. Blunt (1798–1835), probably Maine, Massachusetts, or New Hampshire. Miss Frances A. Motley, 1830–33 Oil on canvas; 35 3/8 x 29 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Promised gift of Barbara and David Krashes, P7.1999.1 Photo by Cheryl Richards Coral necklace: In the past, coral necklaces were thought to protect their wearers from evil and sickness. Pileus: a close-fitting cap that was worn in ancient Rome. It symbolized liberty in neoclassical art.

Lucina Hudson (1787–?), South Hadley, Massachusetts. Liberty Needlework, 1808 Watercolor and silk thread on silk, with metallic thread and spangles, 18 x 16 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase with funds from the Jean Lipman Fellows,1996, 1996.9.1

My Family Album Quilt

Think of important events in your family’s history —maybe the birth of a sibling or a major move to another state far away from loved ones. How willyou tell your story (orstories) in a quilt? What symbols and colors will you use to represent each event and family member? Design your own family album quilt, and write a narrative to accompany it.

My quilt tells a story about…

16

Reproducible Activity Sheet

Curriculum Connections American Anthem Discovery Tours and Story Tours support the Tennessee Curriculum Frameworks by introducing themes that are relevant to visual arts, language arts, and social studies curricula. Specific standards are addressed at age-appropriate levels. An example is shown below. You may view connections for all grade levels (K–12) at www.fristcenter.org.

Example: Sixth Grade Visual Arts 4.0 Historical/Cultural Relationship.The student will speculate on how factors of time and place give meaning or function to a work of art from a variety of cultures, times, and places. 5.0 Reflection and Assessment. The student will understand and apply visual arts vocabulary when observing, describing, analyzing, and interpreting works of art 5.0 Reflection and Assessment. The student will describe and interpret different ways that human experience is reflected in contemporary and historic works of art.

Language Arts 1.0 Reading. (6.1.tpi.8.) The student will make creative responses to texts. 1.0 Reading. (6.1.tpi.10.) The student will express personal reactions to texts. 1.0 Reading. (6.1.tpi.27.) The student will use content specific vocabulary. 2.0 Writing. (6.2.tpi.14.) The student will compare and respond to questions from all content areas. 2.0 Writing. (6.2.tpi.16.) The student will write personal reflections on experiences and events.

Social Studies 1.0 Culture (6.1.tpi.6.) The student will compare various formsof jewelry, art, music, and literature among historical periods. 1.0 Culture (6.1.tpi. 13.) The student will create a piece of artwork based on a historical example. 6.0 Individuals, Groups, and Interactions (6.6.tpi.7.) The student will analyze differing communities' perception of beauty.

Encourage students to look closely at each work of art and consider the following questions:

• The Artist: Who created the work? When did the artist begin making art? Do you think he/she had some sort of formal art training? Why or why not? How and where might the artist have gained his/her skills?

• Purpose: Why did the artist create the work? Does the work of art serve a specific purpose or function? If so, how was it used or where might it have been displayed? If the object is functional, why might its creator have decided to decorate it?

• Ideas: What is the subject matter of the work? Does the work of art reflect the artist’s ideas or beliefs? If so, how?

• Stories: Does the work tell a story about the artist’s personal life or important national events? What objects, props, or symbols does the artist include to help tell the story?

• Materials: What materials did the artist use to create the work of art? Where do you think he/she found these materials? Why do you think the artist chose to use them?

• Techniques: What techniques did the artist use to create the object? Did he/she need any special training, skills, or materials to make the object?

Learning to Look. Looking to Learn. Farm vs. Factory

Look closely at each work and compare the farm and factory. Identify thecharacteristics of the landscapes, the style and purpose of the buildings, the modes of transportation, etc. Record your findings below.

Land Buildings

Transportation

Other Findings

Land Buildings

Transportation

Other Findings

The Residence of Lemuel Cooper, 1879 Paul A. Seifert (1840–1921), Plain, Sauk County, Wisconsin Watercolor, oil, tempera, ink, and pencil on paper; 21 7/8 x 28 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.26 Photo by John Parnell

Unidentified artist, signed “AJH/77” Oswego Starch Factory, possibly 1877 Oswego, Oswego County, New York Watercolor and ink on paper; 36 1/8 x 53 ¼ in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.16.

217

Reproducible Activity Sheet

American Anthem includes more than 130 examples of folk art created for a variety of reasons. The exhibition first focuses on the nation’s early years, when functional objects were embellished with decorative elements in an effort to beautify homes. It then examines ways in which artists celebrated national events and documented important cultural changes. Finally, American Anthem explores contemporary folk art, sometimes called visionary art, outsider art, or art brut, which often contains spiritual and psychological dimensions.

American Anthem

Preparing for your visit… The American Anthem teaching packet was designed with teachers’ needs in mind, and we hope you will find it helpful in preparing students for their visit and in follow up study. The guide opens with a series of questions (“Learning to Look”) that encourage students to look closely and discuss historic and contemporary works of art from the exhibition. Each of the following sections include a timeline, which provides historical context, and a narrative about the artwork, which can be incorporated into class discussion or given as a reading assignment to older students. Designed to be adaptable to all ages, “Making a Connection” activities allow students to reflect and relate the art and ideas to their own lives and experiences. Each activity is accompanied by color reproductions and some have reproducible sheets.

UPPER RIGHT: Attributed to Sturtevant J. Hamblin (active 1837–1856), probably Massachusetts Sea Captain, ca. 1845 Oil on canvas; 27 1/8 x 22 ¼ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of Robert Bishop, 1992.10.2 Photo by John Parnell LOWER LEFT: Unidentified artist, New England Sea Serpent Weathervane, ca. 1850 Paint on wood with iron; 16 1/4 x 23 1/4 x 1 in. American Folk Art Museum purchase, 1981.12.13 Photo by John Parnell

UPPER RIGHT: Bessie Harvey (1929–1994), Alcoa, Blount County, Tennessee Faces of Africa I, 1994 Paint on wood with wood putty, shells,and marbles; 33 x 28 x 17 in. American Folk Art Museum, New York Blanchard-Hill Collection, gift of M. Anne Hill and Edward V. Blanchard Jr., 1998.10.24; Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Gregory “Mr. Imagination” Warmack (b. 1948), Chicago, Illinois Button Tree, 1990–92 Wood and cement with buttons, bottle caps, and nails 56 x 34 x 60 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York Gift of the artist, 2000.13.1 Photo by John Parnell

Compare Two Works of Art What do you see (shapes, colors, textures, etc.)? What did you learn about the artist and the work? What do you think about these two works of art? In the overlapping parts of the circles, write similarities of the works, and in the part of the circles that do not overlap, write the unique characteristics and differences of each work.

Faces of Africa I Button Tree

1 18

Reproducible Activity Sheet

Resources for Teacher and Students Books

Websites

American Folk Art American Folk Art Museum, New York, New York www.folkartmuseum.org Folk Art Society of American www.folkart.org American History Timelines American Memory Timeline, Library of Congress Learning Page (interactive) http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/ American History Timeline, Smithsonian Institute (interactive) http://www.si.edu/resource/faq/nmah/timeline.htm

Teacher Workshop

Learn more about American Folk Art at an interdisciplinary teacher workshop. Teachers of all subjects, K–12, are welcome. Space is limited so please register early. $15 for members $20 for non-members Thursday, February 10 OR Saturday, February 12, 8. To register for a teacher workshop or to obtain information about school tours, visit www.fristcenter.org or call (615) 744-3247.

Archangel Gabriel Inn Sign, 1810–35 For 150 years, this figure of the Archangel Gabriel was a well-known local landmark, mounted above the entry to a building that served as a post office and general store before it became the Angel Inn. It was not uncommon for a figure of Gabriel, in Christian tradition the herald of the Second Coming, to appear as a weathervane on the steeples of churches. Secular settings, such as the Angel Inn, then located on a busy stagecoach route, were also known.

Frist Center for the Visual Arts January 21– May 1, 2005

The Frist Center presents

American Anthem A teacher’s guide to selected works from the exhibition. Featuring historic and contemporary artwork, American Anthem DiscoveryTours and Story Tours encourage students to explore symbols of liberty, ingenuity, and refuge that are embedded in American folk art. This guide is designed to help prepare students for their visit.

A handprint marks topics for discussion and activities for students.

What’s in This Teacher’s Guide? American Anthem Introduction, page 1 “Learning to Look” and Curriculum Connections, page 2 Art in the Home, pages 3–4 Quilt Stories, pages 5–6 Patriotism and Politics, pages 7–8 Changing Worlds, pages 9–10 Twentieth-Century Folk Art, pages 11–14 Reproducible Activity Sheets, pages 15–18 Resources, back cover

Resources Exhibition Catalogue

Anderson, Brooke Davis, and Stacy C. Hollander. American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 2001.

Websites

American Folk Art Museum, New York www.folkartmuseum.org Folk Art Society of America www.folkart.org

American Memory Timeline Library of Congress Learning Page (interactive) http://memory.loc.gov/learn/features/timeline/ American History Timeline Smithsonian Institute (interactive) http://www.si.edu/resource/faq/nmah/timeline.htm

Teacher Workshop

Learn more about American Folk Art at an interdisciplinary teacher workshop. Teachers of all subjects, K–12, are welcome. Space is limited so please register early. $15 for members and $20 for non-members Thursday, February 10 OR Saturday, February 12 8:30 a.m.–3:30 p.m. To register for a teacher workshop or to obtain information about school tours, visit www.fristcenter.org or call (615) 744-3247.

Unidentified artist, Guilford Center Chenango County, New York Archangel Gabriel Inn Sign, 1810–35 Paint on wood; 24 x 46 1/2 x 18 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum New YorkGift of Alice M. Kaplan, trustee, 1997–1989, Museum of American Folk Art, 2001.3.1; Photo by John Parnell

For 150 years, this figure of the Archangel Gabriel was a well-known local landmark, mounted above the entry to a building that served as a post office and general store before it became the Angel Inn. It was not uncommon for a figure of Gabriel, in Christian tradition theherald of the Second Coming, to appear as a weathervane on the steeples of churches. Secular settings, such as the Angel Inn, then located on a busy stagecoach route, were also known. COVER: All artworks collection American Folk Art Museum, New York © 2005 except detail first row, 3rd from left: Art © Robert and Gail Rentzer for Estate of Morris Hirshfield / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum has been organized by the American Folk Art Museum, New York. American Anthem is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc.

2005 Platinum Sponsor: 2005 Gold Sponsor:

919 Broadway, Nashville, TN 37203